Virtual Reality in Self-regulated Learning: Example in Art Domain

Jean-Christophe Sakdavong, Morgane Burgues and Nathalie Huet

CLLE-LTC CNRS UMR 5263, Université Toulouse 2 Jean Jaurès, 5 allée Antonio Machado, Toulouse, France

Keywords: Self-regulated Learning, Self-regulation, Motivation, Immersion, Control.

Abstract: In recent decades, learning devices using virtual reality (VR) environments have evolved rapidly. The

potential positive impact of VR has been attributed to two characteristics: immersion, and control of

interaction with objects in the environment. However, results from the literature have not always shown the

presumed benefits and few of them have assessed the effects on self-regulation. This study aims to assess the

impact of immersion and control on motivation, self-regulation, and performance. Participants had to acquire

knowledge about sculptures by visiting a 3D virtual museum and then recall this knowledge. The participants

were divided into four independent groups. They were: #1 In strong immersion (with VR headset) and active

(control of interaction); #2 In strong (VR) and passive (non-interaction control) conditions; #3 In low

immersion (tablet) and active conditions; #4 In low and passive immersion conditions. Intrinsic motivation

and emotion were evaluated by a questionnaire, self-regulation was identified by behavioral indicators and

performance was evaluated through a gap-fill exercise. Results showed that the "control" feature had a

positive impact on performance, unlike immersion. Also, neither immersion nor control had an impact on

motivation. However, immersion and control had a partial impact on self regulation. Educational implications

will be discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Following the publication of the 2016 Charter for

Cultural Education in Avignon (France), we decided

to join this initiative, which aims to make artistic and

cultural education accessible to all at school, college

and university. In this context, this study focuses on

the learning of artistic knowledge during virtual

museum visits. In recent decades, learning devices

have evolved rapidly through new technologies and

are increasingly used in training sessions and in

museums. However, learning is a complex process,

supported by intrinsic motivation (Black Deci, 2000),

influenced by emotions (Gendron, 2010) and

requiring learners to use self-regulation strategies

(Pintrich, 2000). Using new technologies such as

Virtual Reality (VR) simulation environments may

help students to learn, about art knowledge for

example. The potential positive impact of VR in

learning has been attributed to two characteristics:

immersion and control of interaction with objects in

the environment (Muhanna, 2015). It has been

attested that a VR display is more immersive than a

conventional display and computer (Mikropoulos

Natsis, 2011). However, results from researches have

revealed that performance was not systematically

higher with the use of VR during a learning phase

(Negut et al., 2016). Some authors have found higher

performance in VR than via a lecture-based

curriculum (Dubovi et al., 2017). The lack of

consensus in the results could be due to the degree of

control (active vs. passive) allowed by the immersion

device. Control is characterized by the existence or

lack of possible interaction on the virtual

environment. Participants who can interact with the

environment, such as by selecting or manipulating

objects, are considered as having an active control.

Conversely, participants who cannot interact with

their environment are considered to have a passive

control of their learning. It is recognized in the

literature that being active in learning can improve

performance (Hake, 1998). The interest of these new

technologies is that they enable participants to be

more active in their learning by offering them an

interactive virtual environment.

Twenty years ago, results showed that in VR

environments, an active control immersion was not

always related to a higher performance than that with

a passive immersion (Brooks, 1999). Now recent

papers, with the improvement on VR technology,

Sakdavong, J., Burgues, M. and Huet, N.

Virtual Reality in Self-regulated Learning: Example in Art Domain.

DOI: 10.5220/0007718500790087

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019), pages 79-87

ISBN: 978-989-758-367-4

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

79

have revealed a positive effect of active immersion on

learning performance (Jang et al., 2017).

By referring to the literature (Deci and Ryan,

2000), we expected that the impact of immersion and

control on learning could be explained by an increase

in intrinsic motivation, which is positively related to

learning. Firstly, concerning the impact of the degree

of immersion on motivation, VR is recognized as

impacting motivation positively (Limniou et al.,

2008., Visch et al., 2010). According to the literature

(Dalgarno and Lee, 2010), 3D virtual learning

environments, such as VR, increased motivation and

user engagement in comparison with traditional 2D

learning environments. However, no research has yet

been done specifically on the impact of a high degree

of immersion on the intrinsic motivation. According

to the literature, we expected that immersion would

have a positive impact on intrinsic motivation.

Finally, the literature (Deci et al., 1981) showed that

people with an active control of their learning have a

greater intrinsic motivation than those who have a

passive control of their environment. Referring to

that, we expected that learners who have a high active

control of the objects in a virtual environment would

have a higher control of their learning. We expected

that high control conditions would predict a higher

intrinsic motivation than for those who have a low

control of the objects in the environment.

Learning is also impacted by self-regulation

(Pintrich, 2000), which is an active and conscious

process, allowing the construction of knowledge. As

we have not found any study on the effect of active

immersion on self-regulation, we think it is an

important field to investigate. Finally, we

hypothesize, by referring to learning literature

(Bransford et al., 2000) that a high immersive and

high control condition promotes learning

performance and self-regulation. This study aims to

assess the impact of our independent variables,

immersion and control on our dependant variables:

motivation, self-regulation, and performance.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

Sixty-one students, without any art courses (thirty-six

females and twenty-five males, average age = 22.66,

SD = 3.80), were recruited on the campus of the

University of Toulouse II Jean Jaures, and the

University of Toulouse III Paul Sabatier. Participants

performed the assignment alone, without a classmate

and accompanied only by the experimenter. The lack

of knowledge of art especially of the three target

sculptures used later was checked. All of the students

were completely unfamiliar with art.

2.2 Materials and Groups

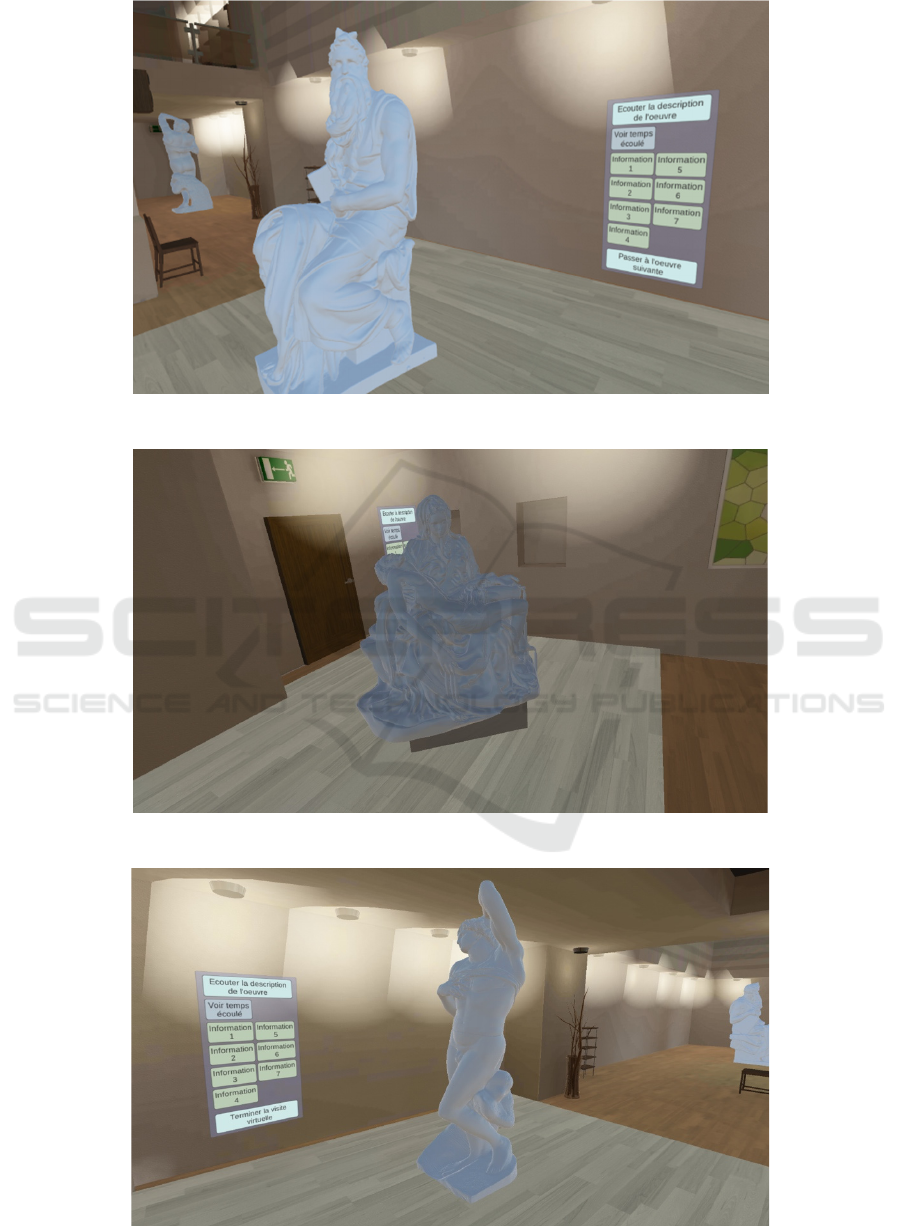

Participants had to acquire new art knowledge in a 3D

virtual museum visit. The digital environment was

specifically designed for the experimentation (c.f.

Figure 1, 2 and 3). The museum contains four

sculptures by Michelangelo to study: “David”,

“Moses”, “Pietà” and “Dying Slave”. The learning

was evaluated for the three last sculpture, while

“David” was used for a familiarization task.

The learning task was a free pace of knowledge

related to the three sculptures. Participants had thirty

minutes to acquire knowledge of the three sculptures

and they use their time freely without constraint. This

was followed by a memory task in the form of a gap-

fill exercise. The task consisted in memorizing

knowledge on each virtual sculpture after hearing

spoken information.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of

four independent groups. The difference between the

groups were the level of immersion and control.

Group #1 was a high immersion and active group

(N=15), its participants had a VR headset and a

pointer remote. They could move around the

sculpture and could obtain information by selecting a

part of the sculpture using the remote. Group #2 was

a high immersion and passive group (N=15), they had

the same VR headset and remote. The perspective

moved automatically around the sculpture, they did

not have to move around the sculpture and they did

not have to select any part of it to get information,

they only click on a panel to get information.

Group #3 and #4 were in low immersion, using an

Android tablet instead of a VR headset and their

finger touch instead of the pointer remote.

They had the same 3D virtual environment. Group

#3, was a low immersion and passive group (N=16)

and group #4, a low immersion and active group

(N=15).

The VR headsets were Google Daydream mobile

headsets having 3 degrees of freedom (3 DoF) with a

3 degrees of freedom pointer remote. The Tablets

were Android HP Pro Slate 12' displaying the 3D

scenes over the 2D screen and using gyrometer and

magnetometer to see around (3 DoF as with the VR

headset).

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

80

Figure 1: Virtual environment “Moses”.

Figure 2: Virtual environment “Pieta”.

Figure 3: Virtual environment “Dying slave”.

Virtual Reality in Self-regulated Learning: Example in Art Domain

81

2.2.1 Familiarization

The familiarization period (identical to the test)

consists in the discovery of one sculpture, the

“David” by Michelangelo.

This familiarization was intended to train the

participant, during ten minutes, to use the material

and its resources. This familiarization period is

specific to each group (tablets or virtual, passive or

active), but they had the same time and the same

knowledge to acquire, according to the conditions.

During the familiarization phase and for all

conditions, the participants discovered that the

museum visit consisted of two activities: visually

observing the sculpture, and hearing information on

the artwork. They could listen two types of

information, a global presentation of the sculptures

and specific information on specific areas of the

artwork. After the familiarization visit, participants

had to do a familiarization test, to have a clear idea

and to know what they would be asked to do for the

actual test. This familiarization test consisted of

completing a gap-fill exercise for sculpture learning

before the actual test. It was specified to the

participants that the exercise on the familiarization

sculpture would not be evaluated, but that the test

with the other three sculptures would be.

2.2.2 The Test

The test consisted of the same steps as the

familiarization period, the visit of three sculptures,

then the completion of a gap-fill exercise.

During the visit, the participants had to listen to

general information about each sculpture, and also to

specific information about details of it (e.g.

information 1 = The legs of the “Moses”, c.f Figure

1). However, the final performance of participants

was evaluated, using the same fill-gap exercises for

each participant.

The sentences for the gap-fill exercises were picked

from the general information and from the detailed

information that they could listen during the visit. For

each of the three sculptures, four gap-fill exercises

were proposed, each with three holes to be completed

by finding the missing words. (e.g : The weight of the

statue rests on a single [leg] and therefore on a foot in

majority. With time the [microcracks] appear on this

foot and go up in the leg, which puts [statue] in

danger; [fill-gap to complete])

This made to a total of 12 words to be found per

sculpture, 36 for the 3 sculptures. When the answers

were correct they scored 1 point score, when there

was no answer or a mistaken one, they got a 0 point

score, the highest score was 12 points per work and

36 points in total.

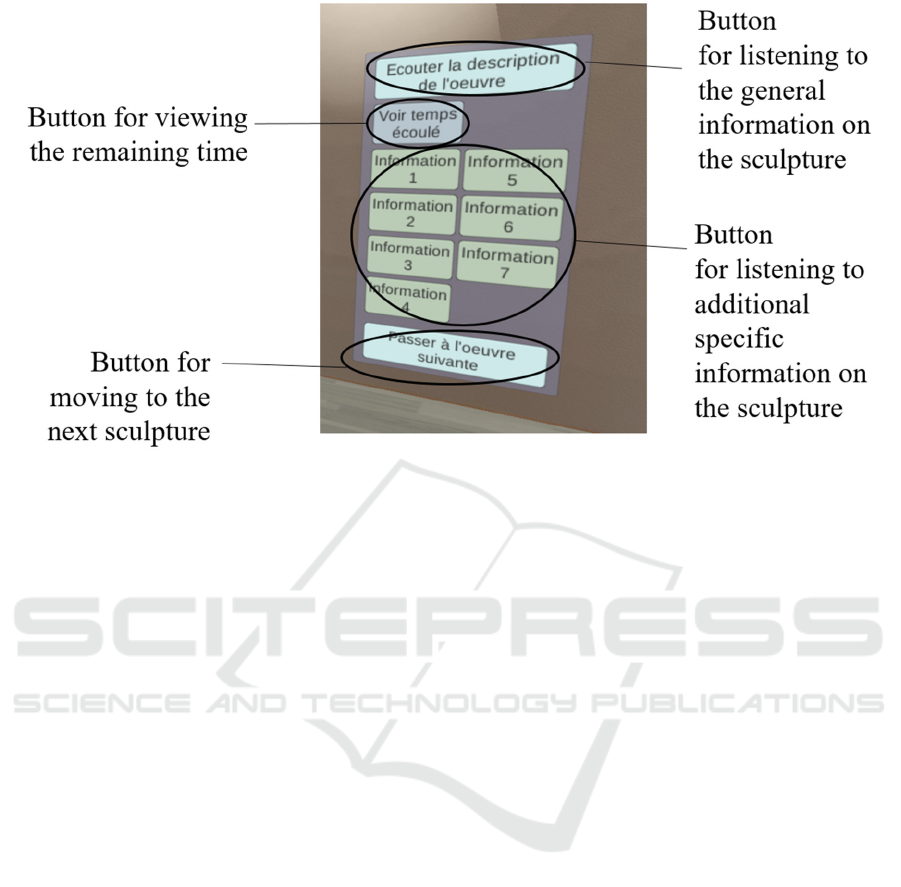

2.2.3 Measure of Self-regulation

To measure self-regulation, two behavioral indicators

were selected in reference to the Pintrich model,

2000. These indicators are operationalised through

the use of control panel by participants (figure 2).

- Time planning, also called “time management”

in the litterature, is operationalised by the number of

clicks on the clock that displays the time elapsed

during their visit (Bouffard-Bouchard and Pinard,

1988)).

- The metacognition indicator (Pintrich, 2000) is

operationalised by the number of times information

heard and replayed (for both general and specific

information).

Each participant's behaviours are recorded and

compiled in the form of traces on a trace server by the

application. Thus, by analysing these traces, each

behaviour is count, as the time consulting or the

number of information and coded "1". Through this

behavior, good self-regulator is learner who consult

regularly the time they have left according to

Bouffard-Bouchard and Pinard (1988). It allows them

to manage their learning by choosing, for example, to

allocate their time to one information rather than

another according to their estimated degree of

memorization.

2.2.4 Measure of Intrinsic Motivation

To measure the motivation, especially the intrinsic

motivation, wich is positively related to performance

(Black and Deci, 2000), we used the questionnaire

from (Deci et al., 1994). It is an adapted French

version of the questionnaire built following the

Vallerand procedure (Vallerand, 1989). This

questionnaire is completed by the participants after

completing the task of learning information about the

three sculptures

It contains 17 items divided into four

subcategories: interest, perception of competence,

pressure, perception of choice (for example, an item

for the dimension of interest: While I was visiting the

museum, I realized how much fun I was having.).

Participants had to indicate their degree of agreement

with the items on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from

"1: Absolutely wrong for me" to "7: quite true for

me". The higher score a participant got in one of the

dimensions, the more it showed that they were in

agreement with it. For example, if a participant had a

high score on the perceived competence it indicated

that they felt competent.

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

82

Figure 4: Control panel.

Similarly, if an individual had a high score in the

"pressure" dimension it meant that they felt under

pressure.

2.2.5 Emotional Perception

Because emotional perception may vary according to

the work of art and may influence learning (Tan,

2000), we checked the potential difference between

the sculptures by assessing the participant’s

emotional perception of each work of art. There was

only one item per sculpture. Participants were invited

to indicate their degree of emotion perceived when

reacting to each sculpture on a 5-point Likert scale,

ranging from 1: no emotion perceived to 5 strong

emotion perceived.

The higher the score in one of the sculptures was,

the more it showed that the individual experienced a

strong emotion.

2.3 Procedure

The first two phases of the study were identical for all

participants. The first phase included the general

instructions, the consent request. It also measured the

level of knowledge of the participants before any

learning and in addition, the individual’s emotional

perception of each sculpture was assessed.

The second phase was to familiarize participants

with the materials according to the condition to which

they were randomly assigned, VR or tablets, active or

passive control. The familiarization also enable them

to become familiar with the gap-fill test, which was

the same for everyone, no matter the condition.

In the third phase, called learning, they visited the

museum with three sculptures and heard spoken

information for each sculpture. Then, demographic

variables were assessed by a questionnaire followed

by the intrinsic motivation questionnaire. Completing

those questionnaires could also be considered as an

interferent task before the recall gap-fill task.

At the end of the experiment, all participants

responded to the three gap-fill exercises successively

by filling the blanks, to measure learning

performance.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Emotional Perception

Results from the one way analysis of variance

(ANOVA) with the sculptures as repeated measures

showed that the three sculptures were not equally

emotionally perceived, F (2,120) = 27.23; p < .001.

The “Pieta” sculpture, was significantly perceived

as arousing the most emotion (M= 3.11; SD = .90).

The other two ones did not arouse a strong emotion,

both were equal (M=2.34; SD = .90 for the “Moses”

sculpture; and M= 2,34; SD = . 96 for the “Dying

slave”).

For the rest of the study, we will use the sculptures

as a repeated measure because of this difference in

emotional perception.

Virtual Reality in Self-regulated Learning: Example in Art Domain

83

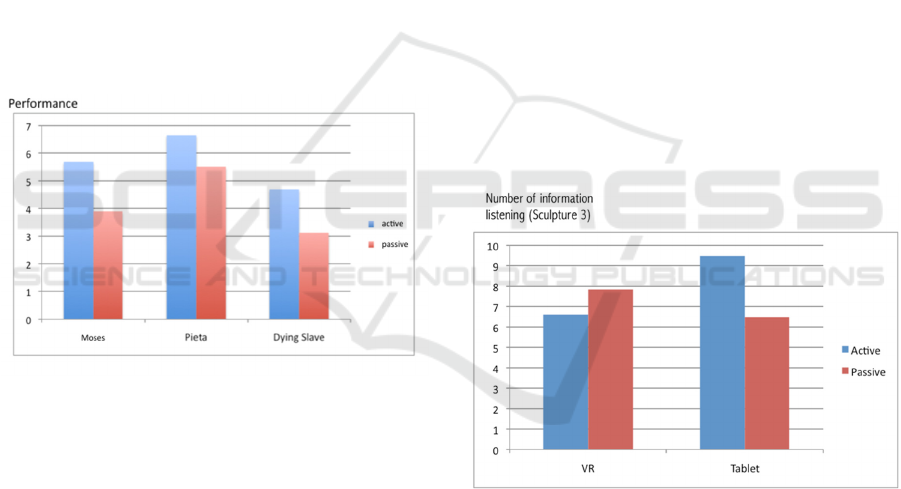

3.2 Performance

A three-way ANOVA with Immersion and Control as

independent factors and the sculpture as the repeated

measure was computed. Results showed a significant

effect of the control condition, F (1, 57) = 8.32; p =

0.006, η2p = 0.13.

Participants in active conditions significantly

outperformed (M = 5.69, SD = 0.37) those in the

passive conditions (M = 4.18, SD = 0.37).

No relationship was found between immersion

and performance, F(1, 57) = 0.22 ; p = 0.64.

A significant effect of the sculpture, F (1,57) =

6.46; p = 0.014, η2p = 0.10 was found. The “Pieta”

was significantly more successful in terms of

performance (M = 6.08, SD = 2.81) than the “Moses”

(M = 4.79, SD = 2.60) and the “Dying slave” (M =

3.90, SD = 2.89).

Finally, no interaction between sculpture and

control was found, F (1,57) = 0.93; p = 0.76, η2p =

0.02 and no interaction between immersion and

sculpture, F(1,57) = 1.97, p = 0.17, η2p == 0.03.

Figure 5: Performance per sculpture according to the

control condition.

3.3 Self-regulation

Two indicators were used to measure self-regulation,

(1): the frequency with which individuals consulted

the time remaining; (2): the number of times

information was listened or re-listened.

Results for the number of time consultations

revealed a significant effect of immersion, F(1,57) =

23,766, p <.001, η2p = .294, and a significant effect

of control, F(1.57) = 4.678, p = .048, η2p = .067. No

interaction effects were revealed, F (1,57) = 304, p =

.584, η2p = .005. Thus, participants in a high-

immersion condition consulted on average more time

(M = 7.96, SD = .80) than participants with low

immersion (M = 2.40, SD = .81). Similarly, active

individuals consulted on average over their remaining

time (M = 6.33, SD = .81) more than passive

individuals (M = 4.03, SD = .80). We did not record

the number of time consultation per sculpture,

preventing us from performing analyzes for each one

of them.

Results for the number of listened and re-listened

information (general and specific) revealed no

immersion effect, F (1,57) = 0.09; p = 0.77, η2p =

.002, no control effect, F (1,57) = 0.44; p = 0.51, η2p

= .008, and no interaction effect, F (1.57) = 3.17; p =

0.08, η2p= 0.05. The number of listened and re-

listened information did not show any significant

difference according to the sculpture, F (1,57) = 1.28.,

p = 0.26, η2p= 0.02.

Only the indicator of Self-regulation “listening

and re-listening” was positively related to

performance, r=.434, p<.001. Moreover, performance

related to the “Pieta” sculpture was positively

correlated with the number of times participants

listened and re-listened, r = 0.26; p = 0.04.

Performance related to the “Dying slave” sculpture

was also positively correlated to the number of times

participants listened and re-listened, r = 0.66; p =

0.004. In contrast, no significant correlation was

found between these variables for the “Moses”

sculpture.

Figure 6: Interaction effect of control and immersion on the

number of times information was listened and re-listened

(general and specific) on the third sculpture.

3.4 Intrinsic Motivation

Anova revealed no effect of immersion, F (1, 57) =

.305; p = .583, η2p = .005, no control effect, F (1,57)

= .168; p = .683, η2p = .003 and no interaction effect

between immersion and control on intrinsic

motivation, F (1,57) = .118; p = .732, η2p = .002.

No effect of immersion, control and interaction

was found on every sub-dimension of intrinsic

motivation. More precisely, no immersion effect was

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

84

revealed for dimension 1 of interest, F (1,57) = .062,

p = .805, η2p = .001, no control effect, F (1,57) =.

306, p = .583, η2p = .005, and no interaction effect, F

(1,57) = 255, p = .616,, η2p = .004. For dimension 2,

perceived competence, no effect of immersion was

found, F (1,57) = .002, p = .967, η2p = .000, of

control, F (1,57) = .175, p = .677, η2p = .003, or

interaction, F (1,57) = 53, p = .819,, η2p = .001. For

dimension 3, perceived choice, the results did not

show any effect of immersion, F (1,57) = 1,042, p =

312, η2p = .018, of control effect, F (1,57) =. 450, p

= .505, η2p = .008, or of interaction effect, F (1,57) =

361, p = 550, η2p = .006. Finally, the Anova on the

dimension 4, pressure, revealed no effect of

immersion, F (1,57) = .188, p = .667, η2p = .003, and

no effect of control, F (1.57) = 1.420, p = .238, η2p =

.024. No significant effect was revealed for

interaction, F (1,57) = 3,463, p = .68, η2p = .057.

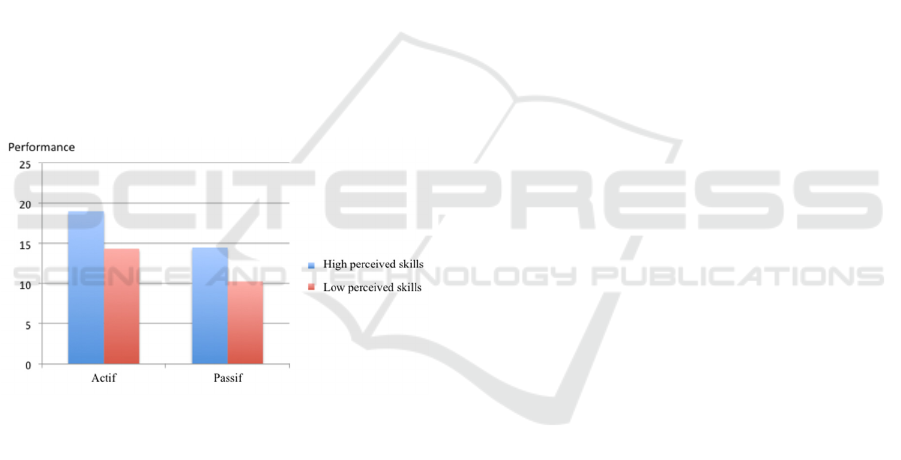

Furthermore, only the sub-dimension 2, perceived

skills, was positively related to performance, r=.35,

p<.05. The global score on the intrinsic motivation

scale was not related to performance, and the three

other sub dimensions were not related to

performance.

Figure 7: Performance rates by control condition and

perceived skills, sub-dimension 2 on motivation scale.

4 CONCLUSION

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of

immersion and control on performance, motivation,

and self-regulation.

In accordance to our hypothesis and the literature,

it appears that learners improved their learning

performance when they were active. Giving the

possibility of controlling the actions during task

allows individuals to be more involved and to use

behavioural self-regulation strategies (Bruner, 1957)

that are conducive to learning. Indeed, the

behavioural strategies of self-regulation “listening

and re-listening” are related to learning, in

accordance to our hypothesis.

It also appears that the different sculptures did not

bring the same perception of emotions. These results

brought us to test our hypothesis on all the sculptures

and on each sculpture independently. Consequently

we believe that further research should be undertaken

to investigate more thoroughly the impact of

emotions on learning and the impact of immersion

and control, using new technological tools for

studying emotions (Pan et al, 2006).

However, contrary to our expectations, immersion

did not have an impact on performance and had no

effect on listening to information. We also found no

relation between immersion, control and intrinsic

motivation and no relation between intrinsic

motivation and performance.

For a better understanding of these results it might

be relevant to consider the theory of cognitive load

(Sweller, 1988). This theory assumes that the load is

limited and must be distributed. However, it is

possible that the resources mobilized to learn how to

use the tool and how to deal with the gap-fill exercise

memory task were excessive. Thus, there was not

enough essential load available to be effective

whatever the conditions. Participants without any

knowledge of art had to manage their learning about

art and their learning of new tools. In this perspective,

a scale of perception of the mental effort was filled by

our participants. The results revealed a significant

perceived effort in using the functionality of the tool,

whether in high immersion with VR (M = 5.61, SD =

1.63, Min: 1, Max: 9) or low immersion with tablet,

(M = 6.37, SD = 1.73, Min: 1, Max: 9). There were

no significant differences in perception of the effort

between the two conditions of immersion, t (59) = -

1.75, p = .085. The extrinsic load of the task was too

important, no matter the condition, thus impeding

learning because it reduced the resources available for

the essential load. For future studies, the reminder

task could be simpler, in the form of a multiple-choice

questionnaire for example, to limit the intrinsic load.

The familiarization phase could be longer to reduce

the extrinsic load. It could also be to reduce the

number of information to be recalled, making the visit

only for a single work of art.

This cognitive overload could also have caused a

competition between the metacognitive activity and

the learning cognitive activity, thus preventing an

appropriate self-regulation behaviour, such as time

management, planning. Furthermore, according to

(Kirschner et al., 2006), a self-exploration task, in

active condition, can lead to too much workload and

thus hinder the very activity of learning.

Virtual Reality in Self-regulated Learning: Example in Art Domain

85

Furthermore, our study was limited to a recall

task; that is the knowledge that needed to be acquired

was on the lowest level of Bloom’s taxonomy

(Anderson et al, 2001); it does not test understanding.

Furthermore, the lack of results for intrinsic

motivation may be due to the fact that our protocol

induces extrinsic and not intrinsic motivation in

participants because of the attractiveness of testing

new technologies rather than of the task of learning

about art. Only one dimension of intrinsic motivation

provides a good prediction of performance: the

perceived competence. This may be linked to the Self

Efficiency Belief of (Bandura, 1986), which is also a

predictor of performance in this theory. To conclude,

we can recommend that learners not be overload,

which can be done by limiting the amount of informa-

tion to be learned and adjusting the recall phase.

In conclusion, it appears that learners improve

their learning performance when they are active.

Having control over the task allows participants to be

more involved and to implement behavioral self-

regulation strategies that are conducive to learning.

However, contrary to our expectations, immersion

affect neither performance nor listening to

information. It should be noted that studies of the

impact of immersion on learning and motivation are

still in their beginning, which explains the number of

contradictory results on this subject. Similarly, no

researches has previously been done on the impact of

immersion in VR on self-regulation, hence the

interest of pursuing research on this topic.

Thus, the virtual learning environment design will

have to take into account a set of factors that have an

impact on performance. New technologies, when

used without taking these factors into account can

lose their educational value.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the research project

LETACOP founded by the ANR (National Research

Agency) – ANR-14-CE24-0032.

The virtual reality development was conducted by

the AD2RV association.

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W.,

Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R.,

Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning,

teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s

taxonomy of educational objectives, abridged edition.

White Plains, NY: Longman.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and

action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986.

Black, A. E., Deci, E. L., 2000. The effects of student self-

regulation and instructor autonomy support on learning

in a college-level natural science course: A self-

determination theory perspective. Science Education,

84.

Bouffard-Bouchard, T., Pinard, A. (1988). Sentiment

d’auto-efficacité et exercice des processus d’auto-

régulation chez les étudiants de niveau collégial.

International Journal of Psychology, 23(1-6), 409-431.

Bransford, J., Brown, A., Cocking, R., 2000. How people

learn: Brain, mind, experience and school. Washington,

DC: Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences

and Education, National Research Council.

Brooks, B. M., 1999. The specificity of memory

enhancement during interaction with a virtual

environment. Memory, 7.

Bruner, J. S., 1957. Going beyond the information given.

Contemporary approaches to cognition, 1(1).

Dalgarno, B., Lee, M. J., 2010. What are the learning

affordances of 3-D virtual environments?. British

Journal of Educational Technology, 41(1).

Deci, E. L., Eghrari, H., Patrick, B. C., Leone, D., 1994.

Facilitating internalization: The self-determination

theory perspective. Journal of Personality, 62.

Deci, E. L., Nezlek, J., Sheinman, L., 1981. Characteristics

of the rewarder and intrinsic motivation of the

rewardee. Journal of personality and social

psychology, 40(1).

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of

goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination

of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Dubovi, I., Levy, S.T., Dagan, E., 2017. Now I know how!

The learning process of medication administration

among nursing students with non-immersive desktop

virtual reality simulation. Computers Education, 113.

Gendron, B., 2010. Capital émotionnel, cognition,

performance et santé: quels liens ? In Du percept à la

décision: Intégration de la cognition, l’émotion et la

motivation. Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgique : De Boeck

Supérieur. Doi : 10.3917/dbu.masmo.2010.01.0329.

Hake, R. R., 1998. Interactive-engagement versus

traditional methods: A six-thousand student survey of

mechanics test data for introductory physics courses.

American journal of Physics, 66(1).

Jang, S., Vitale, J. M., Jyung, R. W., Black, J. B., 2017.

Direct manipulation is better than passive viewing for

learning anatomy in a three-dimensional virtual reality

environment. Computers Education, 106.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., Clark, R. E. (2006). Why

minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An

analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery,

problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based

teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41, 75-86.

Limniou, M., Roberts, D., Papadopoulos, N., 2008. Full

immersive virtual environment CAVE in chemistry

education. Computers Education, 51(2).

CSEDU 2019 - 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

86

Mikropoulos, T. A., Natsis, A., 2011. Educational virtual

environments: A ten-year review of empirical research

(1999–2009). Computers Education, 56(3).

Muhanna A., 2015. Virtual reality and the CAVE:

Taxonomy, interaction challenges and research

directions. Journal of King Saud University, Computer

and Information Sciences, 27.

Negut, A., S-A., Matu., F.Alin Sava., David, D., 2016.

Task difficulty of virtual reality-based assessment tools

compared to classical paper-and-pencil or

computerized measures : A meta-analytic approach.

Computers in Human Behavior, 54.

Pan, Z., Cheok, A. D., Yang, H., Zhu, J. Jiaoying Shi, J.,

2006. Virtual reality and mixed reality for virtual

learning environments. Computers Graphics, 30.

Doi:10.1016/j.cag.2005.10.004

Pintrich, P., 2000. The role of goal orientation in self-

regulated learning. Handbook of self regulation. San

Diego, CA, US: Academic Press.

Tan, E. S., 2000. Emotion, art, and the humanities. In M.

Lewis J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of

emotions. 2nd edition. New York: Guilford Press.

Vallerand, R. J. (1989). Vers une méthodologie de

validation trans-culturelle de questionnaires

psychologiques: Implications pour la recherche en

langue française. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie

Canadienne, 30(4), 662.

Visch, V. T., Tan, E.S. Molenaar, D., 2010. The emotional

and cognitive effect of immersion in film viewing,

Cognition and Emotion, 24(8)., Doi:10.1080/026999

30903498186

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving:

Effects on learning. Cognitive science, 12(2), 257-285.

Virtual Reality in Self-regulated Learning: Example in Art Domain

87