Using Laddering to Understand the Use of Gamified Wearables by

Seniors

Auke Reitsma, Ton Spil and Sjoerd de Vries

Faculty of Behavioural, Management and Social Sciences, University of Twente, Drienerlolaan 5, Enschede, The

Netherlands

Keywords: Gamified Wearable, Health Technology, Gerontechnology, Aging, Human Needs.

Abstract: Gamified wearables have the potential to assist seniors in living independently with a good quality of life.

However, the use of (gamified) wearables by seniors is very limited. The uses and gratifications theory states

that needs motivate the use of computer mediated communication. Therefore, this qualitative study aimed to

find the needs that motivate the use of gamified wearables by seniors. Laddering interviews have been

conducted with a group of 12 seniors that live independently in their own homes. Four needs were identified:

the needs for 1) good health, 2) accomplishment, 3) independency and 4) peace of mind. The need to be

healthy and the need for accomplishment could be fulfilled by the gamified wearable and motivated seniors

to use it. However, the needs for independency and peace of mind were undermined by the gamified wearable

Participants expected the gamified wearable to make them less independent and diminish their sense of

accomplishment of being healthy autonomously. The participants also feared information anxiety caused by

information about their physical health, which they expected to undermine their peace of mind. This study

concludes that a more user-centric design is needed for the gamified wearable to meet the needs of seniors.

1 INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, countries face aging populations, a

development that results in pressure on health care

institutions. This view is supported by Bharucha et al.

(2009, p.1), who state that “the graying of the world

population poses formidable socio economic

challenges to the provision of acute and long-term

healthcare”. Arnrich, Mayora, Bardram and Tröster

(2010) argue that “a massive increase of chronic

disease conditions and age-related illness are

predicted as the dominant forces driving the future

health care” (p.67). These health issues could thus

decrease the quality of life of seniors and increase the

costs of healthcare. It can therefore be argued that

new solutions need to be found.

One of the proposed solutions to this impending

problem is a focus on preventative health care in the

form of health technology. A variety of health

technologies have been researched and potential to

help seniors live independently in their own home

with a high quality of life has been found (Arnrich et

al., 2010; Fritz, Huang, Murphy and Zimmermann,

2014). However, Frisardi and Imbimbo (2011) found

that health technologies are not widely used by

seniors. Thielke et al. (2012) argued that the lack of

fulfillment of specific needs of seniors resulted in

limited use of health technologies. This study will

apply the uses and gratifications (U&G) approach of

Katz, Blumler and Gurevitch (1973) to provide an

understanding of the needs that motivate seniors to

use a recent health technology: the gamified

wearable.

While literature suggests great potential in the use

of gamified wearables as a health technology, Kekade

et al. (2017) found that currently the use of (gamified)

wearables by seniors is very low, similar to other

health technologies. Conci, Pianesi and Zancanaro,

(2009, p.63) argue that “there is no evidence that that

older people reject technology more than people of

other ages; elderly, as anyone else, accept and adopt

technology when the latter meets their needs and

expectations”. This view is supported by the uses and

gratifications approach taken in this study (Katz et al.,

1973), which argues that needs determine which type

of media is used. It is therefore hypothesized that the

limited use of gamified wearables is caused by the

technology not meeting the needs of seniors. This

study therefore aims to find the needs that motivate

seniors to use a gamified wearable for health

purposes. Based on the needs of seniors, this study

aims to provide recommendations for the design of a

92

Reitsma, A., Spil, T. and de Vries, S.

Using Laddering to Understand the Use of Gamified Wearables by Seniors.

DOI: 10.5220/0007708600920103

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2019), pages 92-103

ISBN: 978-989-758-368-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

gamified wearable for seniors. The following

research question is formed: What needs motivate

seniors to use gamified wearables?

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 Health in Seniors

Because of the graying of the population worldwide,

significant health challenges occur, especially for

seniors. According to Tak, Benefield and Mahoney

(2010) the aging population in the US will cause

unprecedented challenges for the long term care

industry as the number of older persons who have

cognitive or physical limitations soars.

In order to face these challenges, a more

preventative health care model is needed (Arnrich et

al, 2010). Preventative health care has the aim of

helping seniors live independently in their own homes

with a high quality of life. While the number of

factors that cause health risks and need preventative

care are numerous, this study is focused on

preventative care in the form of supporting physical

activity, a healthy diet and mental health. According

to the World Health Organization (2002) both

inactivity and an unhealthy diet cause major health

risks, such as strokes, heart disease and cancer.

Besides these two factors, stress was also found as a

cause for heart disease.

2.2 Health Technologies

One of the provided solutions for the pressure on

health care is the use of health technologies to help

seniors live independently in their own homes for a

longer time with a good quality of life. This can be

done in various ways, by providing feedback on

health, reminding seniors to take their medicine, or

assisting them in daily activities.

In recent years the use of technology to motivate

healthy behavior has been a growing area of research

(Fritz et., 2014). According to Zuckerman and Gal-

Oz (2014) this focus on the use of technology to

motivate healthy behaviour is because these

technologies have the potential to improve quality of

life. According to several studies health technologies

do not only have the power to improve life quality,

but can also reduce costs of healthcare (Spil,

Sunyaev, Thiebes and Van Baalen, 2017; Tak et al.,

2010).

It can be concluded from recent literature that

researchers foresee great potential in the use of health

technologies to shift the health care model towards a

more preventative form, as they offer seniors a way

to remain independent for longer, with a higher

quality of life. This study is focused on a recent health

technology: the gamified wearable.

2.3 The Gamified Wearable

According to Kumar et al. (2013) the use of wearable

health information has the potential to reduce the cost

of health care and improve well-being in numerous

ways. The following definition of wearables is used

in this study: “electronic technologies or computers

that are incorporated into items of clothing and

accessories which can comfortably be worn on the

body” (Spil, 2017).

The potential of the use of a wearable as a health

technology has been studied in recent years.

According to Kumar et al. (2013), wearables are able

to “support continuous health monitoring at both the

individual and population level, encourage healthy

behaviors to prevent or reduce health problems,

support chronic disease self-management, enhance

provider knowledge, reduce the number of healthcare

visits, and provide personalized, localized, and on-

demand interventions in ways previously

unimaginable”(p.228). Spil et al. (2017) argue that

wearables “can provide sensory and scanning features

not typically seen in mobile and laptop devices, such

as biofeedback and tracking of physiological

function” (p.3618).

Recent literature suggests the combination of

wearables with a form of gamification, to form a new

health technology: the gamified wearable (Spil et al.,

2017; Tong, Gromala, Shaw and Jin, 2015; Zhao,

Etemad and Arya. 2016a; Zhao et al., 2016b).

Gamification is defined by Deterding, Dixon, Khaled

and Nacke (2011, p.9) as “the use of game design

elements in non-game contexts”. According to

Deterding et al. (2011) gamification can inherently

motivate people by improving engagement.

McKeown, Krause, Shergill, Siu and Sweet, (2016)

agree with this view, identifying gamification as “a

powerful technique to promote engagement and

motivation”(p.67). Cugelman (2013) states that

gamification does work, but only under the right

circumstances and when used in the right way.

According to Cugelman (2013, p.2), “technology is

only persuasive when it employs specific behavior

change ingredients. Pannese, Wortley and Ascolese

(2016, p.1290) argue that “whilst games are

stereotypically associated with the younger

generation, there are significant potential benefits and

a general acceptance of games in the ageing

Using Laddering to Understand the Use of Gamified Wearables by Seniors

93

population”. It can be concluded that gamification has

the potential to motivate healthy behaviour in users.

Zhao, et al. (2016a, p.239) researched the

combination of wearables, gamification and health

and fitness to enhance traditional obesity

intervention. Their study found that “based on

existing technologies and user needs, the idea of

employing wearables activity trackers for

gamification of exercise and fitness is feasible,

motivating, and engaging”. Spil et al. (2017, p.3623)

also found that wearables and gamification can

“function as complementary technologies, which are

strengthening each other”.

While the use of gamified wearables has the

potential to prevent health issues for seniors, Kekade

et al. (2017) found that the current use of wearables

by seniors is very low. It can be concluded from the

available literature that the gamified wearable could

be a promising health technology for seniors because

of its positive effect on users’ motivation to live

healthy. Both wearables and gamification possess

motivational elements and are hypothesized to

strengthen each other. However, use of (gamified)

wearables by seniors is still very limited.

2.4 Uses and Gratifications

To better understand the limited use of gamified

wearables by seniors, this study applies the uses and

gratifications (U&G) approach by Katz et al. (1973).

U&G theory provides an understanding why people

become involved with a certain type of media, which

has great significance in understanding the use of

computer-mediated communication (Ruggiero,

2000). According to Lin (1999, p.200) “uses and

gratifications has proven to be an axiomatic theory in

that its principles are generally accepted, and it’s

readily applicable to a wide range of situations

involving mediated communication”. This paper

argues that gamified wearables are a relatively new

form of computer mediated communication and

therefore the uses and gratifications approach is

applicable to better understand its limited use.

The U&G process follows the premise that users

are aware of their needs and select media to gratify

those needs (Katz et al., 1973). This means that needs

lead to motivations to use certain media (Lin, 1999).

It can be argued from the uses and gratification theory

that the very low use of wearables by seniors found

by Kekade et al. (2017) can be explained by needs of

seniors not being fulfilled. According to Blumler

(1985), needs relevant in the U&G theory are a type

of self-actualization needs, which are described in

Maslow's’ (1970) pyramid of needs. When applying

the U&G approach to health technologies such as the

gamified wearable, it has to be taken into account that

more primary needs from Maslow’s (1970) pyramid

of needs have been found to motivate seniors to use

health technologies (Thielke et al., 2012).

2.5 Expectations

There is a need for health technologies to prevent

health issues and provide independence for seniors.

Researchers foresee great potential in the use of

health technologies to shift the health care model

towards a more preventative form. The gamified

wearable can be a feasible and persuasive health

technology. It has the potential to motivate seniors to

perform physical activity, motivate seniors to eat

healthy and decrease stress levels in seniors. The uses

and gratification theory (Katz et al.,1973) is used in

this study to understand the use of the gamified

wearable, as it proposes that the needs of users

motivates them to use the gamified wearable. Self-

actualization needs of the U&G theory are extended

in this study with safety needs, love/belonging needs

and esteem needs. While gamified wearables have the

potential to fulfil the safety need for good health and

accomplishment, particularly challenging needs to

fulfil are esteem needs such as independence and

love/belonging needs such as sociability and

friendship.

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1 Participants

For this research a group of 12 seniors (60+) that are

still living at home were interviewed about their

needs that motivate the use of gamified wearables. All

participants live in the Dutch regions of Overijssel

and Gelderland. Participants were recruited using a

convenience-sampling approach. The choice for

autonomous seniors still living at home is made as the

gamified wearable is a health technology that helps

seniors to remain independent. The participants are

divided into two age groups, 60-70 and 70+ and two

gender groups, as female and male participants are

interviewed. Participants of both different age and

gender groups were interviewed until a data

saturation had been acquired, as described by

Marshall, Cardon, Poddar and Fontenot (2013). This

means that after a certain number of participants, a

consensus has been reached and all available data has

been gathered. In the study of Guest, Bunce and

Johnson (2006), it was found that after three

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

94

interviews in each heterogeneous group data

saturation was reached. As four heterogeneous groups

could be formed between age group and gender, 12

participants were interviewed. After 12 interviews it

was concluded that for this study, indeed data

saturation was reached, as no new results surfaced.

3.2 Methods

As this is an explorative study a qualitative method is

used. By using interviews this study explores what the

needs of the target group are that motivate them to use

gamified wearables. A means-end approach: the

laddering technique, as described by Reynolds and

Gutman (1988), is used to identify seniors’ needs.

This method is used because, as described by

Reynolds (1985), rather general classifications fail to

provide an understanding, specifically, of how the

concrete aspects of the product fit into the consumer’s

life. With the laddering method it is possible to

determine the consequences for consumers that

originate from product attributes that eventually

results in disclosing the needs of consumers. The

results are shaped as ‘ladders’, built up from an

attribute level, to a consequences level, ending at the

needs level. This means-end approach “views

consumers as goal-oriented decision-makers, who

choose to perform behaviours that seem most likely

to lead to desired outcomes” (Costa, Dekker and

Jongen, 2007, p. 404.) This form as good fit with the

U&G approach used in this study, which states that

users are aware of their needs and select media to

gratify those needs (Katz et al., 1973). Traditionally,

means-end-chains (MEC’s) are built up to the value

level, but Costa et al. (2007 p.412) concluded in their

overview of means-end theory that it offers “an

improved understanding of which are the relevant

consumer needs and which product attributes deliver

those needs”. This study therefore uses laddering to

find needs, instead of personal values.

Before the interview sessions, participants were

asked to fill in a form of consent to conduct the

interview. The form also emphasized that there were

no wrong or right answers. To provide context on the

lifestyle of participants, the interview started with

general questions about the participants’ lifestyles

regarding health and computer mediated

communication. During the laddering stage of the

interview, a free elicitation method was used. This

means that participants were first asked to freely

identify attributes of the different functions and the

design of the wearable. Then they were asked what

the consequences of these attributes were for them

and why they identified these consequences. As an

integral part of the laddering method, during the

interviews, the interviewer kept asking follow up

questions until the need level had been reached or

resistance from the participant to further questions

was encountered. As soft laddering method as

described by Costa et al. (2007) was used, which

means associations between attributes, consequences

and needs were reconstructed subsequently during the

analysis. Interview sessions took between 20 minutes

and 45 minutes to complete. The interviews were

recorded on a mobile phone and took place in the

homes of seniors, or in other locations they preferred

to meet.

3.3 Analysis

The results were analysed by using Atlas.ti. In the

program, the interviews were codified, by clustering

remarks made by the participants under overlapping

codes. For the laddering analysis, remarks made were

codified in groups of attributes, consequences and

needs. After identifying all attributes, consequences

and needs, hierarchical need maps (HNM’s) were

constructed for the functions of the wearable and

design factors. These HNM’s combined the various

‘ladders’ of attributes, consequences and needs.

Following Reynolds and Gutman (1988) a cut-off

point is chosen for the HNM’s to only display the

most informative results. For this study, a cut-off

point of 2 is chosen for the laddering analysis because

of the limited number of participants. This means

only relations are shown if mentioned by at least two

participants. The intention of this study was also the

provide insight in the difference between the two age

groups and genders, but no clear differences could be

identified.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Lifestyle: Health and Technology

During the start of the interview general questions

were asked to provide an overview of the lifestyles of

the participants. Participants of this study were found

to be relatively physically active, with most of them

walking or cycling. Most of the participants

Using Laddering to Understand the Use of Gamified Wearables by Seniors

95

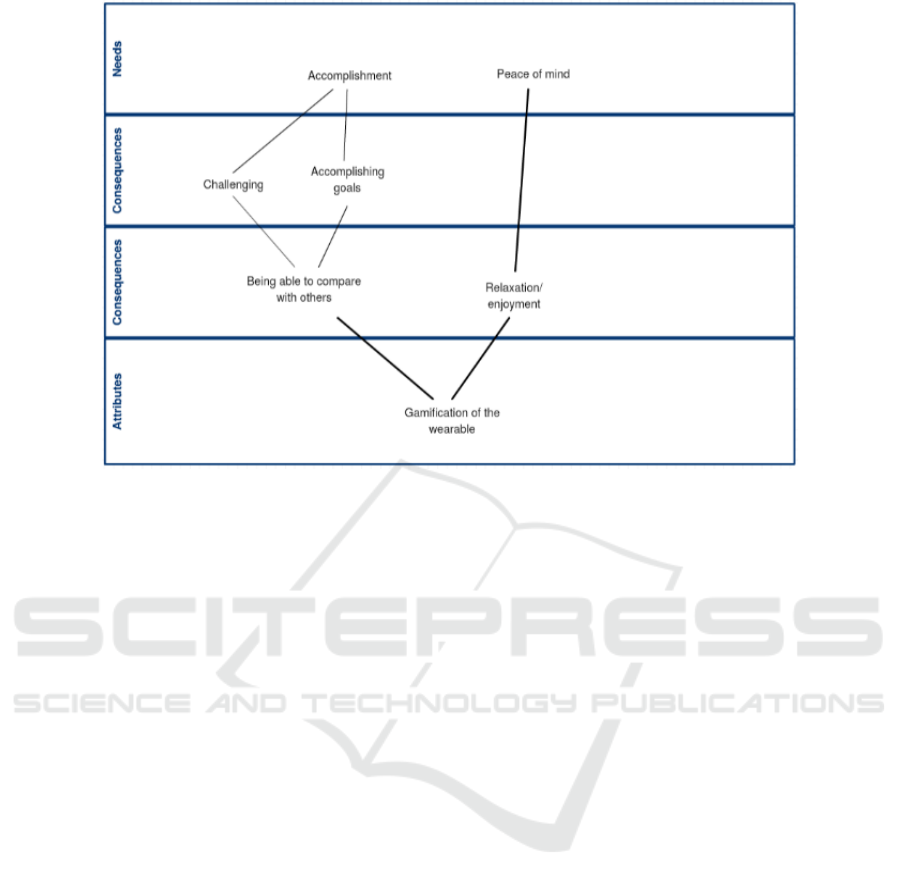

Figure 1: Hierarchical Need Map of Wearable Functions (Cut Off: N=2).

also described themselves as eating relatively healthy.

Participants found living healthy to be important.

Main factors that were of importance for a healthy

lifestyle identified by the participants were physical

activity and a healthy diet.

Participants were also found to be relatively

familiar with the use of computer mediated

communication, with them using it for work, social

purposes, to look up general information, to measure

their exercise or for gaming. It should be noted that

all participants were using computer mediated

communication for at least one purpose.

4.2 Wearable Functions

Part of the interviews focused on the specific

functions of the wearables. Three different functions

of the wearable were discussed during the interviews:

the support of mental health, the support of a healthy

diet and the support of physical activity. The results

of the laddering analysis for the wearable functions

are displayed in a HNM in figure 1. The prevalence

of these relations is indicated by the width of the lines

connecting them.

Attributes of the functions of the wearable that

were identified were the providing of information

about physical health, physical activity, diet and

mental health. Part of the participants expected the

information to be unnecessary and did not want to

receive it. The need found for this consequence is

independence, as participants saw themselves as

being perfectly capable of maintaining their health by

themselves. This was illustrated by one of the

participants saying: “I already walk a lot, so I

wouldn’t know why I would need a thing like that”.

Another participant stated: “no I can do that by

myself, I’ll do that myself”.

Participants did not want to receive information

about their physical health (e.g. blood pressure, heart

rate) because they expected this to have a

consequence of them worrying about the information.

They expected this worrying to have the consequence

of information anxiety, for which the need of peace

of mind was found. The consequence of worrying

about the information was demonstrated by a quote

from one of the participants: “then you will worry

when it's not necessary. For me that would be an

objection to measuring everything exactly”. Another

participant stopped using health technologies because

of this consequence, saying “I was going crazy

because I was constantly occupied with that”.

Other participants expected positive

consequences for the information about diet, physical

activity and mental health. They expected the

information to show useful feedback on stress levels,

their diet and their physical activity. A participant

stated for example: “well, that would give me

information about whether I meet the requirements

for a healthy life”. Participants expected this useful

feedback to help them improve their physical activity

and diet and help them deal with stress. For these

expected consequences the need for good health was

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

96

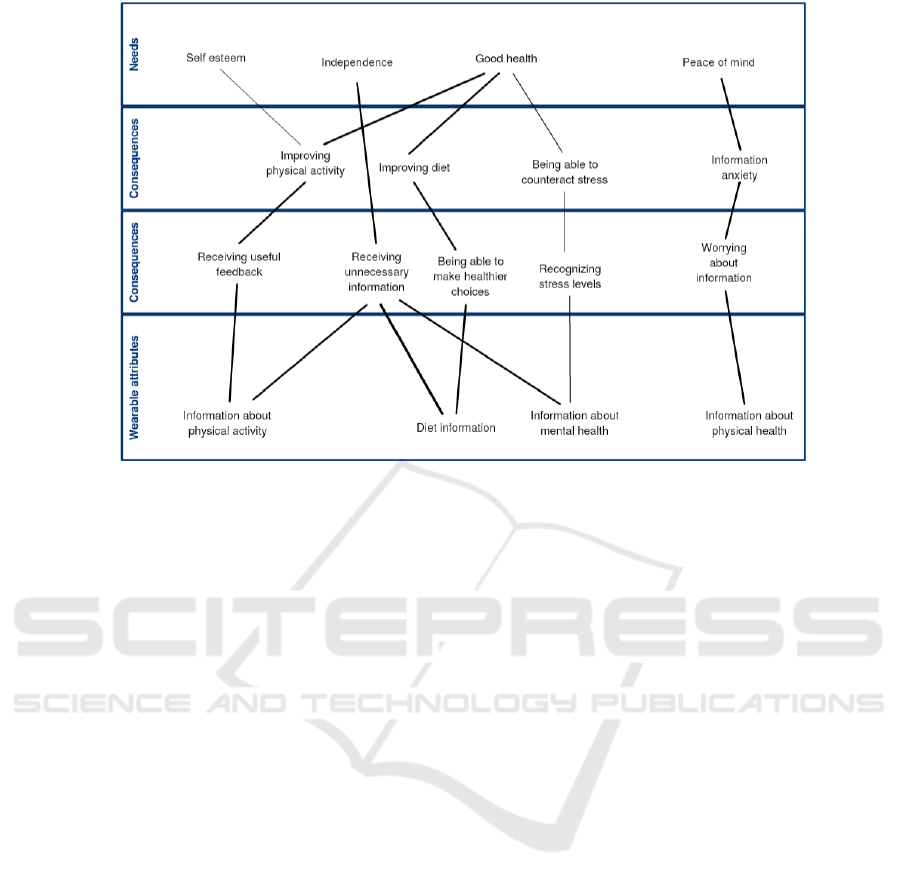

Figure 2: Hierarchical Need Map for Gamification of the Wearable (Cut Off: N=2).

found. A need found specifically for improving

physical activity is accomplishment.

4.3 Gamification

In figure 2 the consequences and needs of

gamification of the wearable are presented in a HNM.

The prevalence of the relations is again indicated by

the width of the lines connecting the relations. A

positive consequence identified is ‘being able to

compare with others’, which refers to the participants

expecting the gamifications to enable them to share

and compare their health information with others.

They mainly referred to data about their physical

activity when describing this consequence, which was

expected to be challenging them, causing them to

accomplish goals and therefore fulfil their need for

accomplishment. One participant stated that “It’s a

challenge towards each other, you can see how many

steps everyone has taken in a week”. Others saw the

ability to play games on the wearable as an

opportunity for relaxation or enjoyment, for which

the need for peace of mind was found.

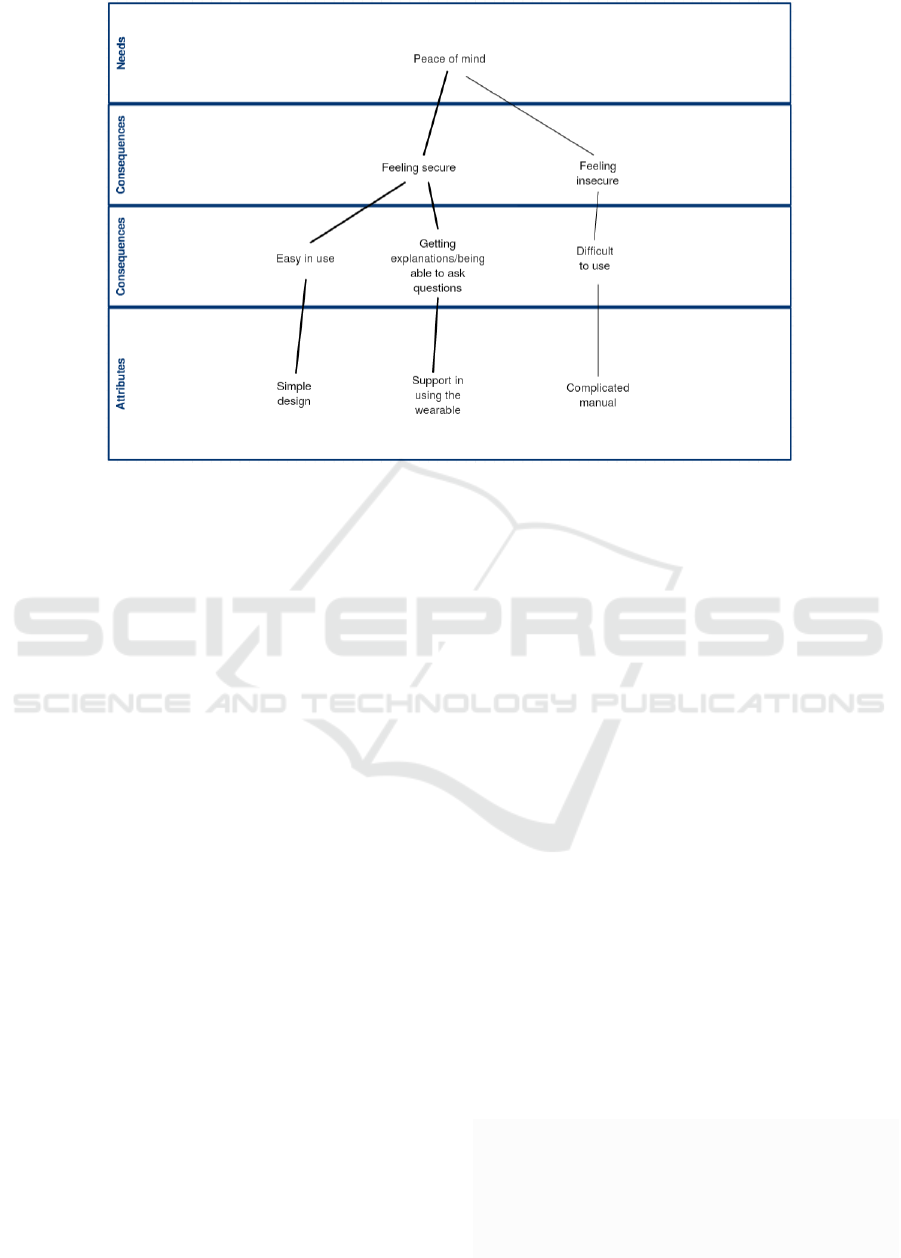

4.4 Design Factors and Support

Besides the functions of the gamified wearable, the

interviews also focused on the design and support for

the use of the gamified wearable. The attributes,

consequences and needs can be found in the HNM

displayed in figure 3. Once more the prevalence of the

relations is indicated by the width of the lines.

One of the attributes discussed by participants is

the perceived simple design of the wearable. This

attribute had the consequence of the gamified

wearable being easy in use, which led to an expected

consequence of feeling secure. For this consequence

a need for peace of mind was found. Support in the

use of the gamified wearable is found to have a

consequence of getting explanations/being able to ask

questions, which also had the consequence of feeling

secure, originating from a need for peace of mind.

Participants identified a complicated manual as an

attribute they often encountered when using new

technology, stating that “manuals for new devices are

sometimes badly designed”. This had an expected

consequence of the gamified wearable being difficult

to use, which in turn had an expected consequence of

feeling insecure. It was found that this consequence

undermined the need for peace of mind.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 U&G Approach and Laddering

Method

In this study a U&G approach is used to understand

the use of gamified wearables by seniors. The premise

of the U&G theory that consumers actively choose

their media use based on their needs offered great

insights in the (limited) use of gamified wearables by

seniors. This line of thinking is supported by the find-

Using Laddering to Understand the Use of Gamified Wearables by Seniors

97

Figure 3: Hierarchical Need Map of the Design Factors and Support of the Gamified Wearable (Cut off: N=2).

ings of other studies that health technologies are

rejected by seniors when they do not fit their needs

(Copelton, 2010; Neven, 2010). This study however

did find the need to extent upon the self-actualization

needs included in the U&G approach, as for health

technologies more primary needs from Maslow’s

(1970) pyramid of needs motivate the use of seniors

(Thielke et al., 2012). Based on the literature review

and results, this study proposes that in order to

understand the use of computer mediated

communication that aims to improve health, such as

health technologies, the including of safety needs and

esteem needs in the U&G approach is necessary.

Seniors were found to be motivated to use the

wearable by 1) the safety need for good health, 2) the

esteem needs for independence and accomplishment

and 3) the self-actualization need for peace of mind.

The need for sociability was expected to be

challenging to fulfil by the gamified wearable, this

need was however not found to be undermined, nor

fulfilled by the gamified wearable. It could be argued

that the gamified wearable is a health technology

aimed at seniors living independently in their own

home, thus not replacing personal health care and

limiting social relations of seniors.

This study uses the laddering technique as

described by Reynolds and Gutman (1988) as its

method. The use of laddering enabled this study to not

only understand the use of gamified wearable by

seniors on a surface level, but to look beyond mere

acceptance and use and offer qualitative insights in

the cognitive structures of seniors regarding the use

of this health technology.

5.2 Lifestyle of Participants

The participants interviewed all had a fairly active

lifestyle, with almost all of them either walking or

cycling regularly. It is important to note this, as the

relatively healthy lifestyle of the participants of this

study could cause them to have other needs than

seniors who are less active.

Participants of this study were also familiar with

computer mediated communication, as all of them

regularly used a type of computer mediated

communication. Only a small minority had used

health technologies before. This familiarity with

computer mediated communication could make

participants feel more at ease in using the gamified

wearable.

5.3 Safety Needs: Good Health

Participants expected the information about their

physical activity, mental health and diet to give them

useful feedback on these health aspects and expected

these attributes to fulfil their need for good health.

The need to be healthy is one of the primary human

needs according to Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of

needs, as it belongs to the ‘safety needs’, which are

the second needs a human has, only above

physiological needs. However, fulfilling the need for

good health only leads to the use of a health

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

98

technology if individuals share the developers

concerns about health (Thielke et al., 2012). That

some participants did not identify the need for good

health to motivate them to use the wearable might

seem contrasting to the hierarchy of needs that states

that the primary needs first have to be fulfilled before

individuals can focus on other needs. However, these

participants might already feel secure in their health,

which causes them to try to fulfil needs higher up the

pyramid of needs, such as the esteem needs and self-

actualization needs described later in this discussion.

It can be concluded that the group of participants that

identified the need for health as motivating to use the

gamified wearable shared concerns about their health

and expected the information about their physical

activity, diet and mental health to fulfil this need.

5.4 Esteem Needs: Accomplishment

and Independence

The need for accomplishment, described as an esteem

need by Maslow (1970) in his hierarchy of needs, was

found when discussing the attribute ‘information

about physical activity’. It can be argued that being

physically active is something seniors are proud of

and through the use of a wearable, can show to others.

It can also be hypothesized that being physically

active is more important for the esteem of seniors than

dealing with stress or eating healthy. Recent studies

still support the notion that people strive for

accomplishment. For example, Crocker and Park

(2004) argue that in domains in which their self-worth

is invested, people adopt the goal to validate their

abilities and qualities, and hence their self-worth.

This study supports this conclusion and shows that,

when provided with information about physical

activity, seniors see this as a way to validate their

abilities and qualities and to help fulfil their need for

accomplishment.

This study found that gamification can also help

to fulfil the need for accomplishment. Participants

expected games to give them the opportunity to

compare their physical activity with others and

challenge them, which they expected to provide them

with a sense of accomplishment. Participants also

expected playing games to be relaxing and to provide

enjoyment, satisfying their need for peace of mind.

The fulfilment of these needs by games is in line with

the motivating strategies composed by Cugelman

(2013), who proposed that in order for gamification

to work and provide a health intervention, social

connectivity and the comparing of progress have to

be present. This study finds that the gamification of

wearables can be very useful in fulfilling the need for

accomplishment of seniors, as it gives opportunities

to set goals and compare oneself with others. It is

found that, in line with previous studies such as that

of Spil et al (2017) and Zhao et al. (2016, a)

gamification provides a useful addition to wearables,

providing the ability to satisfy the needs for

accomplishment and peace of mind.

However, not all participants saw the gamified

wearable as a way to satisfy their esteem needs..

Some participants viewed the information from the

wearable as unnecessary and seemed to have a strong

desire to remain independent of technology to live

healthy. This need for independence is classified as

one of the esteem needs by Maslow (1970). The need

for independence in seniors is prevalent in literature.

Thielke et al. (2012) described the fact that that health

technologies may undermine esteem needs by

limiting independence as a ‘particular challenge’.

Neven (2010) found that the developers of health-

enhancing robots expected their users to want and be

in need of help, but the older adults they surveyed

strongly rejected this position, defining themselves as

capable and independent, and finding the robots

“obviously not for me”. Similarly, elderly with

diminished health expressed that monitoring

technologies would be useful for “the person who

absolutely needs it”, but not for themselves (Mann et

al., 2001–2002).

The gamified wearable is a technology to prevent

mental and physical issues instead of a tool curing

these problems. It can be argued that such preventive

health technologies are not seen as an absolute

necessity to be healthy by seniors. So, as long as

seniors still think they are able to live healthy without

assistance, they prefer to get the feeling of being

independent that comes with it, instead of feeling

reliant on technology. To this group of seniors, the

gamified wearable fails to convince them they can

remain independent longer by using it and does not

adequately address their needs. It can be concluded

that for them, information about their physical

activity, diet and mental health undermines their need

for independence.

5.5 Self Actualization Needs: Peace of

Mind

The attribute of providing information about physical

health (i.e. blood pressure, heart beat) was expected

by participants to make them worry about the

information as a consequence. For example, they

expected it to lead to them worrying about their

slightly high blood pressure. The need that was

undermined by this consequence is the self-

Using Laddering to Understand the Use of Gamified Wearables by Seniors

99

actualization need for peace of mind. This

phenomenon of information leading to worrying is

adequately described as information anxiety by

Bawden and Robinson (2009). This is a new finding,

as information anxiety regarding the use of health

technologies is not discussed in relevant literature.

Besides the content of the information, the frequency

also has the potential to lead to anxiety: instead of

going to the doctor once a year, the participants

expected to get daily worrying information about

their health status. This could lead to information

anxiety through information overload. Bawden and

Robinson (2009) state that “the feeling of overload is

usually associated with a loss of control over the

situation, and sometimes with feelings of being

overwhelmed. In the extreme, it can lead to damage

to health” (p.183). It was found by Given, Ruecker,

Simpson, Sadler and Ruskin (2007) that anxiety and

stress caused by information overload can be

particularly strong in seniors. In this study it was

found that the anxiety from the gamified wearable is

caused by both the potentially worrying nature of the

information as well as the frequency which was

expected by participants to be very high. It can be

concluded that information about physical health,

contrary to other forms of information, undermined

the need for peace of mind.

Other attributes that are of importance in fulfilling

the need for peace of mind were found to be the

design attributes of the gamified wearable, the

support participants received from the manual and

from others in the use of the gamified wearable. The

attribute participants identified in the design of the

wearable was that it had a simple design, meaning

few buttons and other seemingly difficult design

functions. Marschollek et al. (2007, p.258) found that

“The user interface should be intuitive, easy to use,

and adaptable to individual preferences”. This study

shows that a simple design can help fulfil the need for

peace of mind when using the wearable. Besides the

design, participants expected support from others to

enable them to ask questions and understand the

technology better, leading to more security in using

the technology and peace of mind. The findings in

this study are in line with the hypothesis of Phang et

al. (2006, p.6) that “as senior citizens may be

relatively unfamiliar with computers, they may value

support available from surrounding people to solve

the problems that they face in their effort to use

computers”. Furthermore, participants expected the

gamified wearable to have a complicated manual, as

according to them this is often the case when they try

to use new technology. The need for a simple manual

is in line with findings in literature: Kobayashi et al.

(2011, p.95) found that when working with mobile

touchscreens, the elderly participants “were often

confused due to unclear instructions”.

It can be concluded that in order to provide

security in the use of the wearable and to fulfil the

need for peace of mind, seniors need to receive

sufficient support from the manual and from others.

Besides, the design of the gamified wearable needs to

be easy in use, without many more complicated

features.

5.6 Working towards a User Centric

Design

It has been found that several needs of seniors are not

met by the gamified wearable, which, following the

U&G approach (Katz et al., 1973), explains the

limited use of wearables by seniors. This is

problematic, as there is much pressure on the current

healthcare model and health technologies such as the

gamified wearable have the potential to play a role in

the transition to a more preventative healthcare

model. To fulfil the aim of helping seniors live

independently in their own home, this study proposes

several adjustments to its design. The argument that

adjustments are needed to make the design of

gamified wearables more user-centric is strongly

supported by Thielke et al. (2012, p.485), who state

that “many technologies which intend to improve

quality of life, health, and independence may not

address the specific needs which are directly relevant

for individuals”. Besides, “researchers and

developers should remember at all times that users are

at the centre and that technology should be built for

them” (Augusto, 2009, p.12).

While the needs for good health, accomplishment

and peace of mind (by gamification) motivated

participants to use the gamified wearable, the need for

independence and the need for peace of mind (by

information about physical health) are undermined.

This study argues that the undermining of esteem

needs and the need for peace of mind are critical

barriers for the use of the gamified wearable,

following Thielke et al. (2012, p.483), who argue that

“people will not engage consistently in behaviors

which do not satisfy the specific needs which apply

to them at a particular time”.

To overcome the barrier of undermining the need

for peace of mind, several recommendations can be

done. Firstly, peace of mind is expected to be

undermined by seniors because they expect

information about their physical health to give them

information anxiety. This anxiety can be (partly)

removed by designing the gamified wearable in a

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

100

highly adjustable way, allowing seniors to

specifically select the nature and frequency of

information, as well as the way they are notified of

this information. This way, the wearable can fulfil

health needs in specific health areas where seniors

desire assistance, without overloading them with

information or causing information anxiety. Besides

altering the functions of the gamified wearable, a

simple design, support from others and support from

a comprehensive manual can provide security in the

use of the wearable and help fulfil the need for peace

of mind.

Removing the barrier of undermining the need for

independence is far more challenging, because the

very nature of the gamified wearable is to assist

seniors in tasks they are still able to do independently.

However, if the message is conveyed properly that

health technologies such as the gamified wearable can

help seniors live independently in their own homes

with a good quality of life, use can increase. If seniors

accept that the gamified wearable may diminish their

need for independence on a short term, but can help

fulfil it in the long term, this barrier can be overcome.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The U&G method in combination with laddering

proofed to be very valuable in conducting this study.

This study aimed to find the needs that motivate

seniors to use a gamified wearable. Three fulfilled

needs were found: 1) Good health from information

about diet, physical activity and mental health 2)

accomplishment from gamification and 3) peace of

mind from gamification, simple design and support.

Two undermined needs were found: 1) independence,

from information about diet, physical activity and

mental health and 2) peace of mind from information

about physical health. To realize and overcome the

undermined needs, gamified wearables have to be

developed in close harmony with the elderly users as

laid out in the discussion.

7 LIMITATIONS AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

This study calls, following Augusto (2009), for a

more user-centric design of gamified wearables. It

proposes to design the wearable in a more adjustable

way, so users can choose the nature and frequency of

the health information they receive to fulfil their

individual needs. Besides, the design of the gamified

wearable should be simple and support should be

given by others and by a comprehensive manual. This

can increase the sense of security in use and help fulfil

the need for peace of mind.. In order to fulfil the need

for independency, while challenging, new ways

should be found to convey that gamified wearables

can provide independency on the long term, by

preventing health issues. It can be concluded that

while the gamified wearable has the potential to assist

seniors in living independently in their own homes

with a good quality of life, changes in the design are

required to fit the needs of seniors.

This study its main limitation is one often found

with the use of a laddering method: it sometimes

resulted in resistance in the participants. Another

limitation is the validation of the results. While

previous studies found in literature confirm and

explain the needs found in this study, these studies

were done in different contexts and concerned

different health technologies. More studies regarding

the use of gamified wearables by seniors are therefore

necessary, both in a qualitative and quantitative form.

Besides, specific research is needed on the

gamification aspect and the needs of seniors. It is

needed to test different gaming elements and

interview seniors about their opinions. Furthermore,

research is needed on the relation between health

information and information anxiety in seniors, as

this was found to lead to one of the main barriers for

the use of the gamified wearable: the undermining of

peace of mind. Further research is also needed on the

need for independence in seniors, as this seems one

of the most challenging barriers for the use of health

technologies. In depth qualitative research is needed

on how to convey to seniors that the gamified

wearable and other health technologies can assist

them in their independence in the long term, instead

of just diminishing their independence in the short

term.

Lastly, this study proposes more research on the

further possibilities of the gamified wearable, as the

combination of information and gamifications offers

many opportunities. The needs fulfilled or

undermined by a gamified wearable that supports

medicine intake or is used to quit smoking are

examples of areas where research is needed.

REFERENCES

Arnrich, B., Mayora, O., Bardram, J., & Tröster, G. (2010).

Pervasive healthcare. Methods of information in

medicine, 49(01), 67-73.

Using Laddering to Understand the Use of Gamified Wearables by Seniors

101

Augusto, J. C. (2009). Past, present and future of ambient

intelligence and smart environments. In International

Conference on gents and Artificial Intelligence (pp. 3-

15). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2009). The dark side of

information: overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and

pathologies. Journal of information science, 35(2), 180-

191.

Bharucha, A. J., Anand, V., Forlizzi, J., Dew, M. A.,

Reynolds III, C. F., Stevens, S., & Wactlar, H. (2009).

Intelligent assistive technology applications to

dementia care: current capabilities, limitations, and

future challenges. The American journal of geriatric

psychiatry, 17(2), 88-104.

Blumler, J. G. (1985). The social character of media

gratifications. Media gratifications research, 41-60.

Copelton, D. A. (2010). Output that counts: pedometers,

sociability and the contested terrain of older adult

fitness walking. Sociology of health & illness, 32(2),

304-318.

Conci, M., Pianesi, F., & Zancanaro, M. (2009). Useful,

social and enjoyable: Mobile phone adoption by older

people. Human-Computer Interaction–INTERACT

2009, 63-76.

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-

esteem. Psychological bulletin, 130(3), 392.

Cugelman, B. (2013). Gamification: what it is and why it

matters to digital health behavior change developers.

JMIR Serious Games, 1(1).

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011,

September). From game design elements to

gamefulness: defining gamification. In Proceedings of

the 15th international academic MindTrek conference:

Envisioning future media environments (pp. 9-15).

ACM.

Frisardi, V., & Imbimbo, B. P. (2011). Gerontechnology for

demented patients: smart homes for smart aging.

Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 23(1), 143-146.

Fritz, T., Huang, E. M., Murphy, G. C., & Zimmermann, T.

(2014, April). Persuasive technology in the real world:

a study of long-term use of activity sensing devices for

fitness. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 487-496).

ACM.

Given, L. M., Ruecker, S., Simpson, H., Sadler, E., &

Ruskin, A. (2007). Inclusive interface design for

seniors: Image‐ browsing for a health information

context. Journal of the American Society for

Information Science and Technology, 58(11), 1610-

1617.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many

interviews are enough? An experiment with data

saturation and variability. Field methods, 18(1), 59-82.

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and

gratifications research. The public opinion quarterly,

37(4), 509-523.

Kekade, S., Hseieh, C. H., Islam, M. M., Atique, S.,

Khalfan, A. M., Li, Y. C., & Abdul, S. S. (2018). The

usefulness and actual use of wearable devices among

the elderly population. Computer methods and

programs in biomedicine, 153, 137-159.

Kobayashi, M., Hiyama, A., Miura, T., Asakawa, C.,

Hirose, M., & Ifukube, T. (2011, September). Elderly

user evaluation of mobile touchscreen interactions. In

IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp.

83-99). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Kumar, S., Nilsen, W. J., Abernethy, A., Atienza, A.,

Patrick, K., Pavel, M., & Hedeker, D. (2013). Mobile

health technology evaluation: the mHealth evidence

workshop. American journal of preventive medicine,

45(2), 228-236.

Lin, C. (1999). Uses and Gratifications: Audience uses and

gratifications for mass media: A theoretical perspective.

Mann, W. C., Marchant, T., et al. (2001–2002). Elder

acceptance of health monitoring devices in the home.

Care Management Journal, 3 (2), 91–98.

Marschollek, M., Mix, S., Wolf, K. H., Effertz, B., Haux,

R., & Steinhagen-Thiessen, E. (2007). ICT-based

health information services for elderly people: Past

experiences, current trends, and future strategies.

Medical informatics and the internet in medicine, 32(4),

251-261.

Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., & Fontenot, R.

(2013). Does sample size matter in qualitative

research?: A review of qualitative interviews in IS

research. Journal of Computer Information Systems,

54(1), 11-22.

Maslow, A.H. (1970). Motivation and Personality, 2nd edn.

Harper & Row, New York McKeown, S., Krause, C.,

Shergill, M., Siu, A., & Sweet, D. (2016, March).

Gamification as a strategy to engage and motivate

clinicians to improve care. In Healthcare management

forum (Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 67-73). Sage CA: Los

Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Neven, L. (2010). ‘But obviously not for me’: robots,

laboratories and the defiant identify of elder test users.

Sociology of Health & Illness, 32(2), 335–347.

Pannese, L., Wortley, D., & Ascolese, A. (2016). Gamified

Wellbeing for All Ages–How Technology and

Gamification Can Support Physical and Mental

Wellbeing in the Ageing Society. In XIV

Mediterranean Conference on Medical and Biological

Engineering and Computing 2016 (pp. 1287-1291).

Springer, Cham.

Phang, C. W., Sutanto, J., Kankanhalli, A., Li, Y., Tan, B.

C., & Teo, H. H. (2006). Senior citizens' acceptance of

Information systems: A study in the context of e-

government services. IEEE Transactions on

Engineering Management, 53(4), 555-569.

Reynolds, T. J. (1985). Implications for value research: A

macro vs. micro perspective. Psychology & Marketing,

2(4), 297-305.

Reynolds, T. J., & Gutman, J. (1988). Laddering theory,

method, analysis, and interpretation. Journal of

advertising research, 28(1), 11-31.

Ruggiero, T. E. (2000). Uses and gratifications theory in the

21st century. Mass communication & society, 3(1), 3-

37.

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

102

Spil, T., Sunyaev, A., Thiebes, S., & Van Baalen, R. (2017,

January). The Adoption of Wearables for a Healthy

Lifestyle: Can Gamification Help? In Proceedings of

the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences.

Thielke, S., Harniss, M., Thompson, H., Patel, S., Demiris,

G., & Johnson, K. (2012). Maslow’s hierarchy of

human needs and the adoption of health-related

technologies for older adults. Ageing international,

37(4), 470-488.

Tong, X., Gromala, D., Shaw, C., & Jin, W. (2015).

Encouraging physical activity with a game-based

mobile application: FitPet. In Games Entertainment

Media Conference (GEM), 2015 IEEE (pp. 1-2). IEEE.

World Health Organization. (2002). The world health

report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life.

World Health Organization.

Zhao, Z., Etemad, S. A., & Arya, A. (2016), b. Gamification

of exercise and fitness using wearable activity trackers.

In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on

Computer Science in Sports (ISCSS) (pp. 233-240).

Springer, Cham.

Zhao, Z., Etemad, S. A., Whitehead, A., & Arya, A. (2016).

Motivational Impacts and Sustainability Analysis of a

Wearable-based Gamified Exercise and Fitness

System. In Proceedings of the 2016 Annual Symposium

on Computer-Human Interaction in Play Companion

Extended Abstracts (pp. 359-365). ACM.

Using Laddering to Understand the Use of Gamified Wearables by Seniors

103