Wind of Change? Attitudes towards Aging and Use of Medical

Technology

Wiktoria Wilkowska, Julia Offermann-van Heek, Philipp Brauner and Martina Ziefle

Human-Computer Interaction Center, RWTH Aachen University, Campus-Boulevard 57, 52074 Aachen, Germany

Keywords:

Aging, Medical Assistive Technology, Medical Technology Acceptance, Perceived Benefits and Barriers.

Abstract:

Shifts in demographic developments have led to changed needs and requirements in healthcare. Rising life

expectancy and improved medical healthcare enable a more independent and healthier lifestyle of (older) per-

sons, but also changes expectations and perceptions of aging, and health-supporting technologies. Knowledge

about attitudes towards aging, medical assistive technologies, and impacting user factors (especially age and

health status) is limited with regard to a broad sample of participants. In the present study (N=585), we there-

fore examined in an online-survey current attitudes towards aging and quality of life in older age, as well as

perceptions and acceptance of health-supporting technologies, taking age and health status as user factors into

account. Results revealed significant effects of age and health condition on the perception of life quality in

older age. In addition, positive perceptions of aging, technology acceptance, as well as benefits and barriers

were significantly influenced by the respondents’ age. In contrast, health status significantly affected the nega-

tive perceptions of aging. Under impacts of age and health condition as user factors, results of the study allow

a deeper understanding of changing patterns of perceived aging and prevailing opinions regarding acceptance

of medical technology.

1 INTRODUCTION

The increasing aged population represents a big chal-

lenge to the feasibility and sustainability of current

health care. Higher proportions of older people in

need of care, declines of birth rates, and shortage of

care personnel constitute enormous economic, polit-

ical, and in particular social strains for the society

(Pickard, 2015; Deusdad et al., 2016).

In Germany in 2014, these demographic shifts

were characterized by a fifth of the population aged

above 65 years and more than a tenth of the popula-

tion aged above 75 years of age. Moreover, as almost

two thirds of people aged beyond 90 years were in

need of care, the situation of not enough people being

able to pay and care for seniors grows more acute than

ever before (Haustein et al., 2016).

Ubiquitous diffusion of assistive technologies of-

fers the potential to facilitate the work of care person-

nel as well as to support older people in their every-

day life, enabling a largely autonomous living in their

home environments. Besides care-related challenges,

the longer life expectancy of people – due to better

medical health care – leads to growing interests in a

healthier and self-determined living. Here, assistive

technologies offer opportunities to support health-

care by reminding and emergency detecting functions

(Rashidi and Mihailidis, 2013), enabling digital so-

cial interaction (Delello and McWhorter, 2017), or

facilitating everyday life, using automated functions,

like for example documentation of measurements and

smart home functions (Demiris et al., 2008).

In the context of aging, research has long fo-

cused on the deficit approach, which links the pro-

cess of getting older to negative aspects, such as loss

of mental and physical integrity, dwindling interests,

and generally declining skills. However, according

to Baltes (1987) aging is rather a process of losses

and gains. For example, aging is associated with

higher optimism, higher interpersonal trust, and well-

being (Poulin and Haase, 2015). In addition, the older

people are increasingly interested in a healthy living,

in an active shaping their lives, and are more open-

minded towards technology with its assisting devices

and functions (Smith, 2014).

Allowing for the potential technological support

and changes taking place with regard to age and ag-

ing, it is therefore of high interest to empirically in-

vestigate a broad sample of (older) participants, hav-

ing experiences with chronic illnesses. Thus, in this

80

Wilkowska, W., Heek, J., Brauner, P. and Ziefle, M.

Wind of Change? Attitudes towards Aging and Use of Medical Technology.

DOI: 10.5220/0007693000800091

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2019), pages 80-91

ISBN: 978-989-758-368-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

study we examine people’s attitudes towards aging

and their perceptions of medical assistive technology

in relation to their demographic variables of age and

health status.

2 RELATED WORK

This section summarizes the current state of the art,

starting with the research on perceptions of aging,

which is followed by an overview of diverse user

groups’ acceptance of medical assistive technology.

Afterwards, the aim and underlying research ques-

tions of the current study are briefly described.

2.1 Age and Perception of Aging

Aging is “characterized by a progressive loss of phys-

iological integrity, leading to impaired function and

increased vulnerability to death” (López-Otín et al.,

2013, p.1194) and affects all aspects of human life.

It is also associated with higher risks of chronic ill-

nesses and, thus, with higher probability of a need for

medical interventions or care (Jaul and Barron, 2017).

Yet, some negative effects of aging can be miti-

gated by technology: For example, smart homes and

Ambient Assisted Living offer emergency assistance

and autonomy enhancement, increase comfort, and

contribute therefore to aging in place (Rashidi and

Mihailidis, 2013). Thereby, tele-health interventions

can increase the quality of care in older adults, and

also increase health and social functioning (Gellis

et al., 2012). Age-inclusive serious games can sup-

port staying fit, contributing thus to overall well-being

(Brauner et al., 2013). Yet, attitudes and stereotypes

shape how aging is perceived as a societal challenge,

how individuals perceive and deal with their aging,

and probably also their relationship towards assertive

technologies. Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. (2008)

studied self-perceptions of aging and found that most

people feel younger than their chronological age, but

that these differences and satisfaction with aging de-

cline with increasing age. Furthermore, Kotter-Grühn

and Hess (2012) showed that aging stereotypes sig-

nificantly influence the self-image and the percep-

tion of aging, which – in turn – affects attitudes and

behaviors. For example, age is typically linked to

lower self-efficacy in interacting with information and

communication technology (Schreder et al., 2013),

which yields lower use, lower ease of use, and lower

performance of older adults. On the other hand,

studies found that older adults are enthusiastic about

learning new technologies, as long as these are de-

signed responsibly and aligned with interests, values,

and (cultural) expectations of the users (e.g., Heinz

et al., 2013; De Schutter and Vanden Abeele, 2010;

Knowles and Hanson, 2018). In fact, recent studies

show that the use of technologies among older adults

is increasing (Smith, 2014).

Aging, attitudes towards aging and age stereo-

types have been studied as intensively as the require-

ments and handling of technology by older people.

Yet, there is a research gap in the interconnection of

these areas and in the question of how the perception

of medical assistive technologies is shaped by age,

perceptions of aging, or chronic illnesses and care de-

mands, in particular.

2.2 Medical Technology Acceptance

Technology acceptance of future users is an indis-

pensable prerequisite for a sustainable adoption and

everyday use of innovative technologies (Rogers,

2010). In the last years, research on acceptance of

medical technologies found and confirmed that accep-

tance depends on perceptions of technology-related

benefits and barriers. Considering numerous stud-

ies in this research area, assistive technologies were

mostly assessed favorably, while technology benefits

of a more independent and autonomous living, an in-

creased feeling of safety as well as an enabled longer

staying at the own home for (older) people in need of

care are especially appreciated (Gövercin et al., 2016;

Peek et al., 2014).

In contrast, there are also some barriers accompa-

nying the perceived benefits of using assistive tech-

nologies, which have the potential to impede the in-

tegration of such into peoples’ living environments:

These barriers mainly include fears of privacy viola-

tions (Peek et al., 2014; Wilkowska, 2015), and also

feelings of surveillance and isolation (Beringer et al.,

2011; van Heek et al., 2018) in terms of a substitution

of human contact by technology. In addition, research

showed that specific type of technology (Himmel and

Ziefle, 2016) and application context (van Heek et al.,

2016) impact the acceptance patterns.

With regard to non-technical parameters, user di-

versity and specific requirements of different stake-

holders have been proven to influence the technol-

ogy acceptance. Previous research showed differ-

ences in technology perception with regard to gender

(Wilkowska and Ziefle, 2013), health status (Klack

et al., 2011), or experience with care (van Heek et al.,

2017, 2018). Due to the demographic changes it is

thus of importance to analyze age and state of health

(and their interaction) as impacting user factors.

In previous research, age has been frequently ana-

lyzed as influencing demographic variable in the con-

Wind of Change? Attitudes towards Aging and Use of Medical Technology

81

text of technology perception and acceptance (e.g.,

Beringer et al., 2011; Wilkowska and Ziefle, 2013;

Wilkowska, 2015). Compared to that, it is still quite

unclear whether perceptions of benefits and barriers

are impacted by people’s health status and to what ex-

tent it is related to perceptions of aging. Further, inter-

actions between age and health status and their influ-

ence on medical technology acceptance have not yet

been investigated for a broad sample of older adults,

who suffer from chronic illnesses.

2.3 Objectives of the Study

The objective of the present study was therefore to ex-

amine individuals’ current perceptions of aging and

their attitudes towards the use of medical technolo-

gies, which are meant to support seniors or per-

sons with chronic diseases in their everyday duties.

The empirical research was pursued using an online-

questionnaire and special focus was directed to per-

sons of different ages and states of health. Details

about the applied method and the design approach are

presented hereafter.

3 METHOD

Drawing from prior research (Wilkowska and Ziefle,

2013; Schomakers et al., 2018), an online-survey was

conceptualized in order to reach a large sample of par-

ticipants. The study focused on two main issues: The

first focus was on individuals’ perceptions of criteria

which are important for a high quality of life in older

age, and their opinions regarding different effects of

aging itself. The second main focus was on attitudes

towards use of medical technology in health-related

contexts to support persons with health problems or

older and frail adults in their everyday duties.

3.1 Online-survey

The questionnaire used in this study was divided in

three main parts: In the first part, we collected in-

formation about the participants’ socio-demographic

profiles, gathering data regarding their age, gender,

professional background, housing circumstances as

well as general state of health, subjective vitality

(Ryan and Frederick, 1997), and (non-)presence of

chronic diseases. In this section of the survey, par-

ticipants also reported, whether they had experience

with health-supporting devices in their daily lives and

answered questions about their general technical self-

confidence according to Beier (1999).

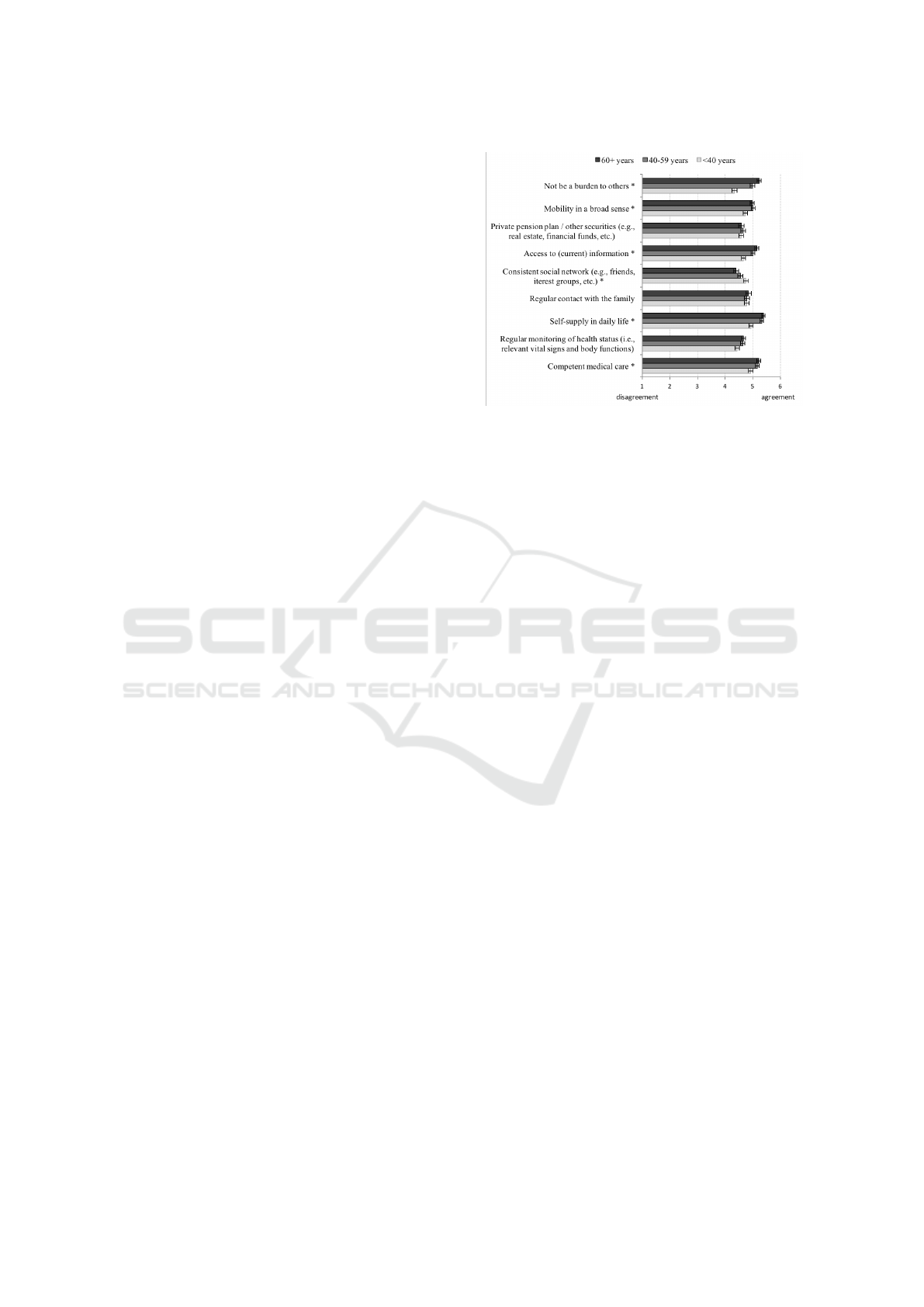

The second part of the survey focused on percep-

tions of criteria which are related to a high quality of

life in old age (QL), like for example competent medi-

cal care, self-supply in daily life, and consistent social

network (all items of this scale are summarized in Fig-

ure 2). Participants assessed the respective items on a

6-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (="I do not agree

at all") to 6 (="I fully agree"). The scale of quality of

aging in old age reached a satisfactory internal con-

sistence of Cronbach’s alpha α=.85. In addition, in

this part of the survey participants’ opinions regarding

positive and negative effects of aging were gathered,

using similar response format; Table 1 contains some

examples of the corresponding items. The scales for

both positive and negative effects of aging reached

very high internal validities (α

pos

=.93; α

neg

=.95).

The third part of the survey focused on partici-

pants’ perceptions of benefits and challenges apply-

ing to the use of health-supporting technologies. A

general attitude towards medical technology (AtMT)

has been collected, using following items:

• "For me, using medical technology makes sense."

• "I do not want to use medical technology."

• "I can imagine the use of medical technology."

The participants could express their (dis-)agreement

regarding these statements on a 6-point Likert-scale.

After re-coding of the negatively poled second item,

the AtMT-scale reached a satisfactory item homo-

geneity of α=.74 with a minimum of 3 and maximum

of 18 possible points. Moreover, participants were

asked to evaluate possible reasons for and against

the use of medical technologies. Thereby, the 6-point

Likert-scale (1=full disagreement to 6 = full agree-

ment) was used once again. Items used as perceived

pros and cons for the use of health-supporting tech-

nologies are explicitly listed in the results section.

Participants were recruited through a professional

survey panel platform, which enabled to gather a rep-

resentative sample of German participants. Partici-

pants were paid for participating by the survey panel’s

institute. The sample’s composition and its character-

istics are described in more detail in subsection 3.3.

3.2 Research Approach

In line with the principle of responsible research and

innovation, this study aimed at the reflection of cur-

rent opinions about the process of aging and the asso-

ciated life circumstances as well as perceptions of the

use of medical technologies as one possible solution

or support for autonomy and independence in older

age. To pursue this objective, following research vari-

ables were chosen for the statistical analyses:

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

82

Table 1: Item examples for the scales of positive (PEoA) and negative effects of aging (NEoA).

Positive Effects of Aging Negative Effects of Aging

"In my opinion, seniors (today)... "I’m afraid that in old age...

...are more mobile and independent than 20 years ... I’ll be a burden to my family."

ago." ... my dignity could be severely compromised

...can maintain their health with lots of physical (e.g., in case of severe illness)."

exercises and careful nutrition." ... my cognitive abilities will shrink."

... can cope better with adversity through his/her ...I would be less mobile due to health restrictions

own experience." and, therefore, socially more isolated."

...have much more time for things they always ... I have more to do with medical equipment than

wanted to do." with other people."

... have to keep up with the latest developments in ...I depend on others."

order to stay up to date."

As independent variables, participants’ age and

health status are taken into account. To understand

potential differences in the perceptions of diverse con-

cepts of aging, it is useful to ask groups of persons

with various amounts of life experience. Therefore,

we divided the sample into three age groups: young

(< 40 years, n=201; 34%), middle-aged (40–59 years,

n=223; 38%), and seniors (≥ 60 years, n=161; 28%).

As it is known from previous research (e.g., Klack

et al., 2011; Wilkowska, 2015), the state of health can

significantly influence perceptions of the concerned

persons. In our statistical analyses we therefore ad-

ditionally examined, whether suffering from chronic

disease has an impact on the respondents’ opinions.

With regard to the health status, 31% of our partic-

ipants reported to be healthy (H) and 61% of them

declared to suffer from chronic illnesses (CI), like

for example cardiac arrhythmia, Crohn’s disease, thy-

roid cancer, asthma, anorexia, multiple sclerosis, and

much more.

Aspects considered dependent variables in this

study applied to aging and use of medical technology,

and are summarized as follows:

• Quality of life in old age (QL): A minimum of 9

and maximum of 45 point could be achieved.

• Positive effects of aging (PEoA): Respondents

could reach between 11 and 66 points.

• Negative effects of aging (NEoA): This scale

ranged from minimum 13 to maximum 78 points.

• Attitude towards medical technology (AtMT)

which reached between 3 and 18 points.

• Perceived benefits for the use of health-supporting

technologies (pros).

• Perceived challenges for the use of health-

supporting technologies (cons).

The research design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research design of the present study (MT = med-

ical technology).

3.3 Participants

The sample of this study intended to cover a broad

spectrum of the German population, including young,

middle-aged, and old individuals with and without

chronic conditions, with different life experiences, ed-

ucation levels, professional backgrounds, as well as

persons with various attributions of a general techni-

cal self-confidence and levels of experience with the

use of medical equipment.

This study collected and analyzed data of N=585

participants, ranging in age between 16 and 84 years

(M=47.2; SD=16.6) and 48% of them were female

(52% male). As the highest educational levels, partic-

ipants reported to hold an academic degree (21.5%)

and 35.7% completed an apprenticeship. Over 19%

of the sample reported to hold a university entrance

diploma, and 23.6% a secondary school certificate.

Less than half of the sample (44.3%) reported to use

and have experience with health-supporting devices

in everyday life, like for example with blood pres-

sure meters, blood sugar meters, heart rate monitors,

wheeled walkers, and activity monitors.

Different professions were represented in the

sample, including engineers, teachers, physiothera-

Wind of Change? Attitudes towards Aging and Use of Medical Technology

83

pist, economists, psychologists, IT-managers, self-

employed businessmen, technicians, caterers, and

many more. About 65% of the respondents reported

to live together with at least one other person or fam-

ily, while 35% used to live alone. Choosing state-

ments with regard to the financial situation, 45% of

the sample declared "I have to count every penny, but

I make ends meet", 46% stated that they’re doing rela-

tively well, and around 9% of them reported that they

lack nothing in financial terms.

4 RESULTS

For statistical calculations of the influence of inde-

pendent variables on perceptions of aging and use

of medical technologies, we executed (multivariate)

analyses of variance [(M)ANOVA] to examine dif-

ferences between the age groups (the significance of

omnibus F-Tests was taken from Pillai values) and

T-Tests for verification of differences between the

groups of various states of health. The parameter par-

tial eta squared (η

2

) was calculated for effect sizes

according to Cohen (1988). For continuous vari-

ables, Pearson’s product-moment correlation coeffi-

cients (ρ), and for dichotomous variables Spearman’s

rank correlation coefficients (r

s

), were calculated. For

descriptive analyses, the means (M) and standard de-

viations (SD) are reported in the following. The level

of statistical significance (p) was set at the conven-

tional level of 5%.

4.1 Concepts of Aging

In the first step of statistical analyses, we examined

influences of the independent variables, i.e., age and

state of health, on perceptions of quality of life in old

age and on positive and negative effects of aging.

4.1.1 Quality of Life in Older Age

An univariate analysis of variance revealed a signifi-

cant effect of age on the specific aspects, accounting

for a high quality of life. The respondents of the three

age groups differed especially regarding competent

medical care [F(2,581)=3.9, p=.021], independence

[self-supply in daily life: F(2,580)=12.7, p6.001; not

being a burden: F(2,580)=30.4, p6.001], mobility

[F(2,581)=4.7, p=.009] and social involvement [so-

cial network: F(2,581)=3.5, p=.030; access to current

information: F(2,579)=11.7, p6.001]. Figure 2 pic-

tures these differences. Generally, from the descrip-

tive results it can be seen that assessments of aspects,

accounting for high life quality in old age reached

Figure 2: Effect of age on aspects accounting for high life

quality in old age [significant differences between the age

groups are marked with an asterisk (*)].

high means in all age groups. Nevertheless, there was

a certain pattern in it, which recurred in almost every

significantly differing aspect: While in most cases the

youngest age group reached the lowest mean values,

the senior age group agreed most with the aspects,

which were associated with high quality of life.

In addition, the effect of health status was exam-

ined in this context and exposed significant differ-

ences between healthy and chronically ill persons re-

garding following criteria of life quality:

• competent medical care [T(580)=-4.5, p6.001]:

thereby, chronically ill persons (CI: M=5.2,

SD=1) valued this aspect significantly more than

healthy individuals (H: M=4.8, SD=1.1);

• self-supply in daily life [T(579)=-2.2, p=.027],

which was higher valued in CI (M=5.3, SD=0.9)

than in H (M=5.1, SD=1); and

• not being a burden to others [T(579)=-2.5,

p=.012], where – again – chronically ill persons

(M=4.9, SD=1.2) desired this aspect more than

healthy ones (M=4.6, SD=1.2).

Figure 3 shows the main effect of the health status.

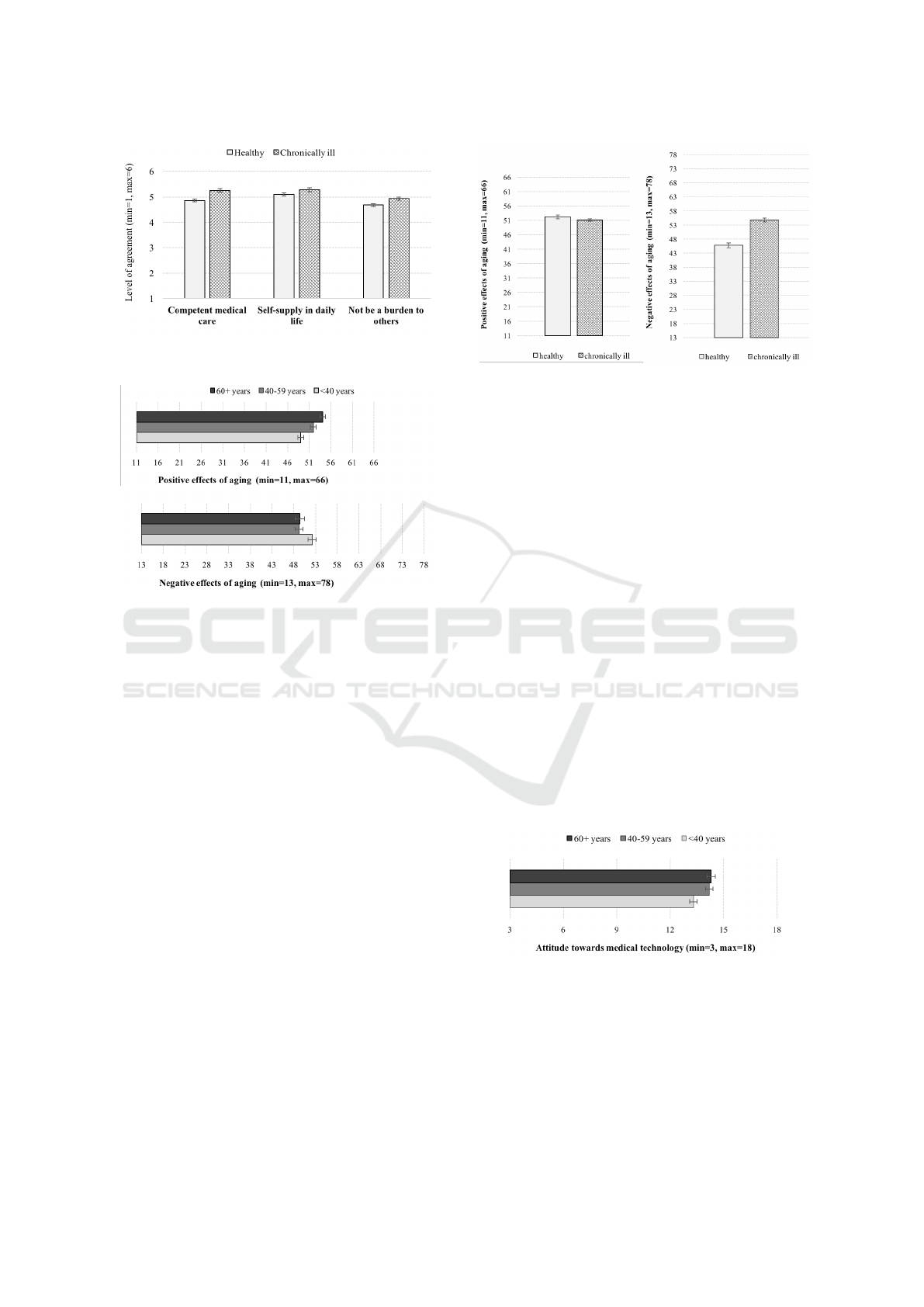

4.1.2 Positive and Negative Effects of Aging

In the next step, in a multivariate analysis of variance

influences of age and health condition were examined,

taking positive and negative effects of aging into ac-

count. The statistical calculations revealed main ef-

fects of both age [F(4,1156)=9.6, p6.001, η

2

=.03]

and health status [F(2,577)=34.8, p6.001, η

2

=.11].

The age differences in perceptions of positive as-

pects of aging are shown in Figure 4 (top): The old-

est respondents in the sample scored with the high-

est mean values in this regard, demonstrating that

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

84

Figure 3: Effect of health status on aspects accounting for

high life quality in old age.

Figure 4: Influence of age on positive (top) and negative

(bottom) effects of aging.

they are the most positive with respect to the pro-

cess of growing older among their younger coun-

terparts. Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey

HSD test indicated that the mean score for young

age group (M=49, SD=8.8) was significantly differ-

ent from the one of the senior age group (M=54.1,

SD=6.7) and the middle-aged age group (M=51.9,

SD=10.1); the latter two differed significantly too.

This result is also mirrored in the perceptions of

the negative effects of aging (see Figure 4, bottom),

where the youngest participants (M=52.2, SD=12.9)

showed significantly higher values than the older ones

(middle-aged: M=49.3, SD=15; seniors: M=49.4,

SD=12.5).

The resulting effect of health condition on PEoA

and NEoA is depicted in Figure 5, whereby the

explicit differences on the between-subject level

were much evident for perceptions of negative

[F(1,583)=63.2, p6.001, η

2

=.01] than for positive

effects of aging [F(1,583)=1.8, n.s.]. In terms of

content, this means that persons with chronic ill-

ness (M=54.8, SD=12.7) were significantly more pes-

simistic with respect to the process of growing older

than the healthy individuals (M=46.3, SD=13.4). Fur-

thermore, no interaction effect of age and health was

found in the context of positive and negative percep-

tions of aging.

Figure 5: Influence of health condition on positive (left) and

negative (right) effects of aging.

4.2 Perceptions of Medical Technology

The second main objective of this study was to gain

knowledge about the currently prevalent opinions re-

garding deployment of health-supporting technolo-

gies. In this section we analyze effects of age and

health condition in this context: We firstly examine

influence of these factors on a general attitude towards

the use of medical technology (MT), and observe it

afterwards for the perceived pros and cons.

4.2.1 General Attitude Towards MT

An univariate analysis of variance revealed that

age significantly affects the attitude towards the

use and the meaningfulness of medical technology

[F(2,573)=5.7, p=.004, η

2

=.02]. According to the ef-

fect size the effect was small, but it is easy to see in

Figure 6 that both older age groups of participants

(middle-aged: M=14.3, SD=3; seniors: M=14.2,

SD=2.7) manifested higher values on the scale than

the young age group (M=13.4, SD=2.9).

Figure 6: Influence of age on general attitude towards med-

ical technology (AtMT).

Health status, on the other hand, did not sig-

nificantly affect attitudes to the health-supporting

technology [F(1,573)=2.9, n.s.] and there was no

interacting effect of age and health status, either

[F(2,573)=0.7, n.s.].

Wind of Change? Attitudes towards Aging and Use of Medical Technology

85

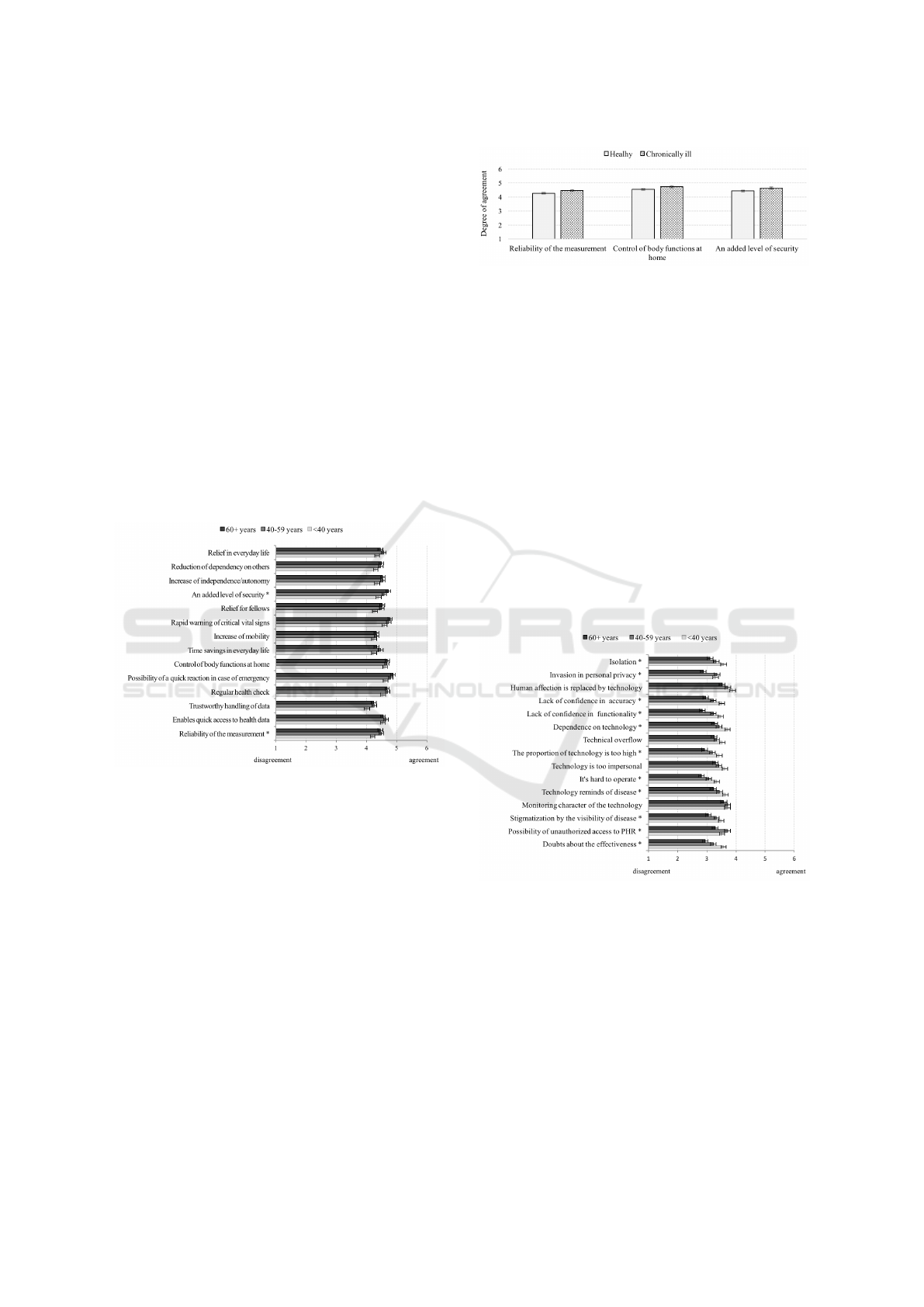

4.2.2 Reasons For the Use of MT (Pros)

There are many benefits resulting from the use of

eHealth technologies which are supporting frail per-

sons in their everyday life. In this section, we exam-

ine if participants’ opinions regarding these perceived

pros differ depending on their age and state of health.

For this purpose, in the statistic analysis univari-

ate ANOVA was calculated for benefits which are de-

picted in Figure 7. The three age groups reached quite

high average values – a result that shows that there

was a high consensus about the many advantages of

eHealth technology. The means mostly did not dif-

fer significantly between the age groups, excepting

the opinion that MT provides an added level of se-

curity [F(2,575)=4.5, p=.012] and its measurement is

reliable [F(2,575)=3.8, p=.023]. Regarding theses as-

pects, the young age group was on average less con-

vinced about these benefits in comparison to the both

older age groups.

Figure 7: Means in the age groups regarding perceived rea-

sons for the use of medical technology [significant differ-

ences are marked with an asterisk (*)].

If considering these opinions between persons

with and without chronic conditions significant dif-

ferences resulted for similar aspects: reliability of the

measurement [T(574)=-2.1, p=.031], regular control

of body functions at home [T(574)=-2, p=.043], and

an added level of security [T(574)=-2.3, p=.024].

As depicted in Figure 8, the differences were quite

small. Though, the individuals with chronic illnesses

saw in each of these perceived benefits a significantly

higher value in comparison to the healthy persons.

4.2.3 Reasons Against the Use of MT (Cons)

Eventually, the impacts of age and health condition

were examined regarding challenges associated with

the use of eHealth.

Figure 8: Means in groups of healthy and persons with

chronic illness regarding reasons for the use of medical

technology.

In contrast to the pro-arguments presented above,

statistical analyses revealed major influence of age

on multiple contra-arguments: doubts about the ef-

fectiveness [F(2,575)=10.7, p6.001], possibility of

unauthorized access to personal health records (PHR)

[F(2,575)=4.8, p=.008], stigmatization by the visibil-

ity of disease [F(2,575)=5, p=.007], technology re-

minds of disease [F(2,575)=4, p6.018], technology

is hard to operate [F(2,575)=7, p6.001], the propor-

tion of technology is too high [F(2,575)=6.2, p=.002],

dependence on technology [F(2,575)=5.1, p=.006],

lack of confidence in the technology’s functionality

[F(2,575)=10.1, p6.001], lack of confidence in the

technology’s accuracy [F(2,575)=7.8, p6.001], in-

vasion in personal privacy [F(2,575)=6.6, p=.001],

and isolation [F(2,575)=4.8, p=.009]. In fact, the

Figure 9: Means in age groups regarding reasons against

the use of medical technology (significant differences are

marked with an asterisk (*).

perceptions of disadvantages are overall rather reluc-

tant. However, looking at Figure 9 which shows the

mean values in the respective age groups, similar pat-

tern can be observed almost without exception. On

average, the youngest age group reached in almost

all cases the highest values regarding the perceived

challenges, followed by the means of the middle age

group. In contrast, the senior age group disagreed

with these cons – and this was evident through means

lower than the middle of the scale – and reached al-

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

86

ways the smallest values compared to the participants

of the both younger age groups. This result showed

a quite high acceptance of eHealth technology among

the older part of the population. Furthermore, healthy

persons and individuals with chronic illness did not

differ with regard to the reasons against the use of

medical assistive technology. Statistical verification

by means of T-Test for independent samples brought

no significant effects for these groups.

4.3 Correlative Relationships between

the Research Variables

In the final step of statistical analyses, correlative rela-

tions between the research variables were performed

to get a holistic overview over the study data. To

do so, scale values were formed for the perceived

pros and cons of the use of medical technology (pros:

α=.96; cons: α=.95). The outcomes are summarized

in Table 2.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients showed clearly

that the factor age was significantly connected to al-

most all dependent variables of the present study.

Even when the associations were not very strong, the

outcomes indicated that the older the respondents,

the more inclined were they to aging and the related

circumstances of life (QL: ρ=.14, p6.001), and the

more positive was their attitude towards aging (ρ=.23,

p6.001) and medical technology (ρ=.16, p6.001).

Also, with increasing age the perceptions of argu-

ments pro using medical technology were more affir-

mative (ρ=.10, p=.021), while arguments against its

use were more refusing (ρ=-.15, p6.001).

Correlations regarding the respondents’ health

condition, and in particular the presence of a chronic

disease, indicated that individuals suffering from

chronic illness tend to be more affirmative to the nega-

tive effects of aging (r

s

=.32, p6.001), but on the other

side also more positive towards medical technology

(r

s

=.10, p=.014) than healthy persons.

In addition, the correlative analyses confirmed

strong interrelations between the research variables:

For example, there was a very strong positive corre-

lation between perceptions of quality of life and pos-

itive effects of aging (ρ=.72, p6.001). Affirmative

attitude towards life quality was also strongly posi-

tively connected to the perceived pros of the use of

MT (ρ=.64, p6.001) and to the general attitude to-

wards MT-deployment (ρ=.52, p6.001). In contrast,

the perceptions of reasons against the use of health-

supporting technology (cons) correlated moderately

with the scale of negative effects of aging (ρ=.38,

p6.001) and, correspondingly, with the attitude to-

wards medical technology itself (ρ=-.40, p6.001).

5 DISCUSSION

The aim of the presented study is to reflect current

opinions on two significant trends that increasingly

affect and concern aging societies – especially most

populations in the industrial countries. The first trend

is the ever growing proportion of seniors in popula-

tions that has been rising sharply and becoming more

and more a socio-economic burden to the country.

The second is pervasive computing in the domestic

environments and thus the private spheres of the res-

idents, which is not only progressively miniaturized,

complex, mobile, sophisticated, and unobtrusive, but

which also increasingly covers health-related fields,

with the potential of systematic monitoring of bodily

functions. These two crucial trends gave rise for this

study and were observed in the German population.

We discuss these issues in the following, taking the

previously presented findings into account.

5.1 The Bright and Dark Side of Aging

The long-term challenge of a relentlessly aging popu-

lation is a well-known phenomenon and is intensively

discussed in scientific circles from various points of

view (e.g., Uhlenberg, 2009). The fiscal burden con-

nected to this phenomenon is, thereby, not only asso-

ciated with economic issues due to costs arising from

the growing public pension system (Bloom et al.,

2011), but there are also huge costs accounting for

provision of healthcare to the seniors, as with age

the need for medical care increases sharply (Bosworth

and Burtless, 1998).

The resulting consequences and aspects, which

have a direct impact on daily life, also increasingly

occupy people’s minds. Perceptions of aging and the

associated circumstances have undergone a transfor-

mation at least since the beginning of the 21

st

cen-

tury. In these changing times, not only the think-

ing but also behavior of people intensively changes

with the long-term aim for ’aging well’. According

to Kotter-Grühn et al. (2009), satisfaction with one’s

own aging and feeling young are indicators of positive

well-being in late life. It was also found that negative

self-perceptions of aging as associated with physical

losses might impair health-related strategies that are

important for maintaining a healthy lifestyle (Wurm

et al., 2013). According to the presented results, a

higher consciousness of a variety of aspects for a high

quality of life in old age is necessary: There is need

for health-related and financial security, for social life,

and contact with family but especially autonomy and

independence in daily life reached in the queried sam-

ple the highest mean values. Even though all the ex-

Wind of Change? Attitudes towards Aging and Use of Medical Technology

87

Table 2: Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the research variables [Spearman’s r

s

for health condition: healthy=1,

chronically ill=2; level of significance: *p6.05, **p6.01, ***p6.001].

QL PEoA NEoA AtMT Pros Cons

Age .14*** .23*** -.02 .16*** .10* -.15***

State of health .09* -.02 .32** .10* .06 .01

Quality of life in old age (QL) – .72*** .27*** .52*** .64*** -.02

Positive effects of aging (PEoA) – .11** .49*** .62*** -.09*

Negative effects of aging (NEoA) – .13** .25*** .38***

Attitude towards medical technology (AtMT) – .63*** -.40***

Reasons for the use of MT (Pros) – -.17***

Reasons against the use of MT (Cons) –

amined aspects were judged approvingly for a good

life quality, basically the senior age group perceived

these aspects as significantly more important than the

young age group. A unique exception is related to a

consistent social network. Hereby, the younger part

of the population attributes significantly higher rele-

vance to the social interaction than the older one. This

is most probably a quite recent phenomenon emerg-

ing from the use of social media and social platforms

in the last years. However, the conclusion that so-

cial interaction is more important for younger that

for older persons can be misleading, given the differ-

ent concepts of what is meant with "social network"

for the persons concerned. As opposed to younger

people, older generations did not grow up with tech-

nology that enables intensive social contacts – even

when only in a virtual form – with peers and fam-

ily. What makes it even more difficult is the fact that

getting older also means to be tormented by many

losses: Part of the family members and friends may

have died by then, and building up new friendships is

no longer self-evident nor easy. In consequence, older

people feel increasingly isolated or perceive this state

generally as unpleasant or frightening. It is therefore

conceivable that, for seniors, the idea of maintain-

ing social contacts completely differs from the one of

younger generations.

Surprisingly, these generation differences concern

also the desire of being no burden to others. One

could expect more consensus about this aspect of ag-

ing well among the participants, but according to the

results respondents of the senior age group attach sig-

nificantly more attention to their independence and

are much more willing to make efforts to not be a bur-

den to others than their younger counterparts. These

outcomes differ from earlier research in this context

(e.g., Wilkowska and Ziefle, 2013). In addition, opin-

ions differ depending on the current health condition.

In order to reach a high life quality in old age, persons

with frail health or suffering from chronic illnesses at-

tach considerably higher importance to a competent

medical care, self-supply and autonomy in everyday

life than individuals without any health-related prob-

lems. Apparently, it is the personal relevance of the

issue (i.e., getting older and/or suffering from chronic

illness) which makes people perceive their circum-

stances more positively and to be more open-minded

about actively approaching possible solutions.

Because the results refer to the German popula-

tion, it remains an interesting question whether these

differences regard rather to a changing attitude due to

an easier access to various possibilities of health care

and medical support, or, whether these are culturally

shaped opinions.

5.2 The Interplay between Aging and

Use of Medical Technologies

Drawing from the present research approach, this

study makes evident that a positive attitude towards

the changes caused by aging comes along with a more

optimistic behavioral expectation for an active deal-

ing with the challenges brought by aging and illness.

Also, the high quality of life in old age is in line with

a high attitude towards the use of medical technology

and – considering the opinions regarding its benefits

– perceived usefulness.

As technology is integrated into most aspects of

life and increasingly changes our ways of working,

communicating, and performing our daily routine ac-

tivities (Boot et al., 2018), individuals come more

into contact and interact with it in different contexts.

Technology is also increasingly being used within

healthcare, giving especially to seniors broad possi-

bilities for (more) independent structure and organi-

zation of their day-to-day health management, well-

being, safety and security, as well as their social in-

teraction.

Health-supporting technologies, such as medical

assistance at home and health care monitoring, have

a great potential to help to meet the challenges of ag-

ing in place. However, attitudes towards technology

significantly contribute to technology acceptance and

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

88

are important predictors of technology adoption (Lee

et al., 2018). According to this study’s results, the atti-

tude towards use of medical technologies is generally

positive: The reached average values prove that the

participants find health-supporting technology useful

and are mostly willing to use it. Unexpectedly, our

findings indicate that the younger part of the popula-

tion is slightly less enthusiastic about its deployment

and wide-ranging potential. One possible explanation

for this situation is that most of the young people do

not depend on medical assistance, and/or do not know

anybody who does, and simply cannot yet imagine the

real need and the support it can bring. Still, the preva-

lent attitude suggests that – at least in Germany – peo-

ple are positive about the technology and will use it

corresponding to their demands. This assumption is

also confirmed by the not existent effect of health sta-

tus on the attitude towards medical technology, since

the relatively positive mindset in this regard is appar-

ent even without a concrete ’reason’ which could be

an existing illness.

Moreover, reasons for the use of medical assis-

tive technology are obvious and there is a high con-

sensus about it in the population. In our study, this

argument is substantiated for the most part by the ab-

sence of differences between the examined user pro-

files. Although there are small differences regard-

ing perceptions of the reliability of the measurement

and added level of security, when using medical tech-

nology between young age group and seniors, and

also between healthy and chronically ill individuals,

the participants agreed about the majority of the per-

ceived benefits. In contrast, regarding challenges and

reasons against the deployment of digital assistance

in home environments the opinions are significantly

divided: The respondents of the senior group in our

study simply disagreed with most of the named dis-

advantages, showing a high willingness to make use

of the potential brought by this technology. On the

contrary, young adults reach on average the highest

values with respect to the perceived challenges in al-

most all cases; the means of the participants of the

middle-aged group lie in-between.

These results are not consistent with current stud-

ies on general technology and computer use (e.g.,

Mitzner et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018), where attitudi-

nal barriers that affect technology uptake among older

adults are still higher than among young adults, and

the perceptions of self-efficacy and behavioral inten-

tion still point to a generally lower willingness to use

computer-based technologies among older potential

users. This discrepancy leads to the conclusion that

either adoption of medical technologies is subject to

its own dynamics of acceptance or it testifies that the

adoption behavior of such health-supporting technol-

ogy in the today’s seniors have changed, alongside

changes in fields of nutrition, movement, and mo-

bility when getting older. Additionally, it cannot be

ruled out that research on long-term adoption of med-

ical technology among seniors needs such extended

acceptance models, as the ones used in the research

of Chen and Chan (2014), who assessed digital prod-

ucts and services that could enhance independent liv-

ing and social participation for older adults. For this,

further examination and validation studies are neces-

sary.

5.3 Limitations and Future Research

Although the study provided detailed and relevant in-

sights, it is important to note some limitations, which

should be considered for future work.

Indeed, the presented study is based on a repre-

sentative sample and, therefore, forms a very good

basis for generic statements. However, we only in-

cluded opinions of adults from the German popula-

tion, which limits the validity of the conclusions for

the international forum. In addition, the examined

user factors were limited to age and chronic illness,

but acceptance, and thus successful adoption of med-

ical technologies, is most likely influenced by other

user characteristics, like for example gender, previous

experience with computer-aided technology, and even

income or financial situation of potential users. Fur-

ther, considering the possible change in the percep-

tions of their own contribution to the process of aging,

it would be also of interest to examine whether there

are significant differences between younger (60-80

years) and older seniors (80 years and older) in their

perceptions of the focal points covered here. Hence,

future studies will need to address these limitations.

Another issue regards the methodological ap-

proach: In the current study we examined partici-

pants’ attitudes towards medical technology on the

basis of only three self-developed statements. In fu-

ture studies, it would be desirable to review this set-

ting more closely and supplement existing survey in-

struments. Finally, the study depicts only the cur-

rent state, but systematic long-term studies are nec-

essary to confirm true changes in perceptions, accep-

tance, and therefore, adoption of health-supporting

technologies among persons concerned.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Medical technology affords a great potential in the

graying societies of today. Health-supporting appli-

Wind of Change? Attitudes towards Aging and Use of Medical Technology

89

cations bring many benefits for older adults and per-

sons with chronic illnesses, providing the possibility

of (more) independent and active aging in place. This

article provides insights into currently prevalent per-

ceptions of aging in the German population, showing

significant associations between positive attitudes in

this regard and the perceived benefits brought by the

use of medical technologies in home environments

that may affect technology uptake among older and

frail adults. The findings allow a deeper understand-

ing of changing patterns regarding aging and the ac-

ceptance of health-supporting technology in modern

societies, and show the impact of users’ individual

profiles on their autonomous shaping of everyday life.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all participants for their contribu-

tion in the survey. This work has been funded by the

project PAAL, funded by the German Federal Min-

istry of Research and Education (reference number

6SV7955).

REFERENCES

Baltes, P. B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-

span developmental psychology: On the dynamics be-

tween growth and decline. Developmental Psychol-

ogy, 23(5):611–626.

Beier, G. (1999). Kontrollüberzeugungen im Umgang mit

Technik [Locus of control when interacting with tech-

nology]. Report Psychologie, 24(9):684–693.

Beringer, R., Sixsmith, A., Campo, M., Brown, J., and Mc-

Closkey, R. (2011). The “acceptance” of ambient as-

sisted living: Developing an alternate methodology to

this limited research lens. In International Confer-

ence on Smart Homes and Health Telematics, pages

161–167. Springer.

Bloom, D. E., Boersch-Supan, A., McGee, P., Seike, A.,

et al. (2011). Population aging: facts, challenges, and

responses. Benefits and compensation International,

41(1):22.

Boot, W., Charness, N., Czaja, S., Rogers, W., and Sharit,

J. (2018). Aging and leisure activities: Opportunities

and design challenges. Innovation in Aging, 2(Suppl

1):213.

Bosworth, B. P. and Burtless, G. (1998). Aging societies:

The global dimension. Brookings Institution Press.

Brauner, P., Calero Valdez, A., Schroeder, U., and Ziefle, M.

(2013). Increase Physical Fitness and Create Health

Awareness through Exergames and Gamification. The

Role of Individual Factors, Motivation and Accep-

tance. In Holzinger, A., Ziefle, M., and Glavini

´

c,

V., editors, Proceedings of the SouthCHI 2013, LNCS

7946, pages 349–362. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidel-

berg, Maribor, Slovenia.

Chen, K. and Chan, A. H. S. (2014). Gerontechnology

acceptance by elderly hong kong chinese: a senior

technology acceptance model (stam). Ergonomics,

57(5):635–652.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behav-

ioral sciences. 2nd.

De Schutter, B. and Vanden Abeele, V. (2010). Designing

meaningful play within the psycho-social context of

older adults. In Proceedings of the 3rd International

Conference on Fun and Games, pages 84–93.

Delello, J. A. and McWhorter, R. R. (2017). Reducing the

digital divide: Connecting older adults to ipad tech-

nology. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(1):3–28.

Demiris, G., Hensel, B. K., Skubic, M., and Rantz, M.

(2008). Senior residents’ perceived need of and pref-

erences for “smart home” sensor technologies. Inter-

national journal of technology assessment in health

care, 24(1):120–124.

Deusdad, B. A., Pace, C., and Anttonen, A. (2016). Fac-

ing the challenges in the development of long-term

care for older people in europe in the context of an

economic crisis. Journal of Social Service Research,

42(2):144–150.

Gellis, Z. D., Kenaley, B., McGinty, J., Bardelli, E., Davitt,

J., and Ten Have, T. (2012). Outcomes of a telehealth

intervention for homebound older adults with heart or

chronic respiratory failure: A randomized controlled

trial. The Gerontologist, 52(4):541–552.

Gövercin, M., Meyer, S., Schellenbach, M., Steinhagen-

Thiessen, E., Weiss, B., and Haesner, M. (2016).

Smartsenior@ home: Acceptance of an integrated am-

bient assisted living system. results of a clinical field

trial in 35 households. Informatics for health and so-

cial care, 41(4):430–447.

Haustein, T., Mischke, J., Schönfeld, F., and Willand, I.

(2016). Older people in germany and the eu.

Heinz, M., Martin, P., Margrett, J. A., Yearns, M., Franke,

W., Yang, H.-I., Wong, J., and Chang, C. K. (2013).

Perceptions of Technology among Older Adults. Jour-

nal of Gerontological Nursing, 39(1):42–51.

Himmel, S. and Ziefle, M. (2016). Smart home medical

technologies: users’ requirements for conditional ac-

ceptance. i-com, 15(1):39–50.

Jaul, E. and Barron, J. (2017). Age-Related Diseases and

Clinical and Public Health Implications for the 85

Years Old and Over Population. Frontiers in Public

Health, 5(December):1–7.

Klack, L., Schmitz-Rode, T., Wilkowska, W., Kasugai, K.,

Heidrich, F., and Ziefle, M. (2011). Integrated home

monitoring and compliance optimization for patients

with mechanical circulatory support devices. Annals

of biomedical engineering, 39(12):2911.

Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, A., Kotter-Grühn, D., and Smith,

J. (2008). Self-perceptions of aging: Do subjective

age and satisfaction with aging change during old age?

The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 63(6):P377–

P385.

ICT4AWE 2019 - 5th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

90

Knowles, B. and Hanson, V. L. (2018). The Wisdom of

Older Technology (Non)Users. Communications of

the ACM, 61(3):72–77.

Kotter-Grühn, D. and Hess, T. M. (2012). The impact of

age stereotypes on self-perceptions of aging across the

adult lifespan. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B,

67(5):563–571.

Kotter-Grühn, D., Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, A., Gerstorf,

D., and Smith, J. (2009). Self-perceptions of ag-

ing predict mortality and change with approaching

death: 16-year longitudinal results from the berlin ag-

ing study. Psychology and Aging, 24(3):654.

Lee, C. C., Czaja, S. J., Moxley, J. H., Sharit, J., Boot,

W. R., Charness, N., and Rogers, W. A. (2018). At-

titudes toward computers across adulthood from 1994

to 2013. The Gerontologist.

López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. a., Partridge, L., Serrano, M.,

and Kroemer, G. (2013). The Hallmarks of Aging.

Cell, 153(6):1194–1217.

Mitzner, T. L., Savla, J., Boot, W. R., Sharit, J., Charness,

N., Czaja, S. J., and Rogers, W. A. (2018). Technol-

ogy adoption by older adults: Findings from the prism

trial. The Gerontologist.

Peek, S. T., Wouters, E. J., van Hoof, J., Luijkx, K. G.,

Boeije, H. R., and Vrijhoef, H. J. (2014). Factors in-

fluencing acceptance of technology for aging in place:

a systematic review. International journal of medical

informatics, 83(4):235–248.

Pickard, L. (2015). A growing care gap? the supply of

unpaid care for older people by their adult children in

england to 2032. Ageing & Society, 35(1):96–123.

Poulin, M. J. and Haase, C. M. (2015). Growing to trust:

Evidence that trust increases and sustains well-being

across the life span. Social Psychological and Person-

ality Science, 6(6):614–621.

Rashidi, P. and Mihailidis, A. (2013). A survey on ambient-

assisted living tools for older adults. IEEE journal of

biomedical and health informatics, 17(3):579–590.

Rogers, E. M. (2010). Diffusion of innovations. Simon and

Schuster.

Ryan, R. M. and Frederick, C. (1997). On energy, personal-

ity, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflec-

tion of well-being. Journal of personality, 65(3):529–

565.

Schomakers, E.-M., Offermann-van Heek, J., and Ziefle, M.

(2018). Attitudes towards aging and the acceptance of

ict for aging in place. In International Conference on

Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population, pages

149–169. Springer.

Schreder, G., Smuc, M., Siebenhandl, K., and Mayr, E.

(2013). Age and Computer Self-Efficacy in the Use of

Digital Technologies: An Investigation of Prototypes

for Public Self-Service Terminals. In Stephanidis, C.

and Antona, M., editors, Proceedings of the Univer-

sal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. User and

Context Diversity, LNCS Volume 8010, pages 221–

230. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Germany.

Smith, A. (2014). Older adults and technology use. Pew

Research Center, http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/

04/03/older-adults-and-technology-use/ (accessed:

2018-12-18).

Uhlenberg, P. (2009). International handbook of population

aging, volume 1. Springer Science & Business Media.

van Heek, J., Arning, K., and Ziefle, M. (2016). The

surveillance society: Which factors form public ac-

ceptance of surveillance technologies? In Smart

Cities, Green Technologies, and Intelligent Transport

Systems, pages 170–191. Springer.

van Heek, J., Himmel, S., and Ziefle, M. (2017). Help-

ful but spooky? acceptance of aal-systems contrasting

user groups with focus on disabilities and care needs.

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference

on Information and Communication Technologies for

Ageing Well and e-Health, ICT4AWE 2017, pages 78–

90. SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publica-

tions.

van Heek, J., Ziefle, M., and Himmel, S. (2018). Care-

givers’ perspectives on ambient assisted living tech-

nologies in professional care contexts. In Proceedings

of the International Conference on ICT for Aging well

(ICT4AWE 2018), pages 37–48.

Wilkowska, W. (2015). Acceptance of eHealth technology

in home environments: Advanced studies on user di-

versity in ambient assisted living. Apprimus Verlag.

Wilkowska, W. and Ziefle, M. (2013). User diversity as

a challenge for the integration of medical technology

into future smart home environments. In User-Driven

Healthcare: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Ap-

plications, pages 553–582. IGI Global.

Wurm, S., Warner, L. M., Ziegelmann, J. P., Wolff,

J. K., and Schüz, B. (2013). How do negative

self-perceptions of aging become a self-fulfilling

prophecy? Psychology and Aging, 28(4):1088.

Wind of Change? Attitudes towards Aging and Use of Medical Technology

91