Towards Simulated Morality Systems:

Role-Playing Games as Artificial Societies

Joan Casas-Roma

1

, Mark J. Nelson

2

, Joan Arnedo-Moreno

3

, Swen E. Gaudl

1

and Rob Saunders

1

1

The Metamakers Institute, Falmouth University, Cornwall, U.K.

2

Department of Computer Science, American University, Washington D.C., U.S.A.

3

Estudis d’Inform

`

atica, Multimedia i Telecomunicaci

´

o, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

rob.saunders@falmouth.ac.uk

Keywords:

Role-Playing Games, Multi-Agent Systems, Morality Systems, Artificial Societies.

Abstract:

Computer role-playing games (RPGs) often include a simulated morality system as a core design element.

Games’ morality systems can include both god’s eye view aspects, in which certain actions are inherently

judged by the simulated world to be good or evil, as well as social simulations, in which non-player characters

(NPCs) react to judgments of the player’s and each others’ activities. Games with a larger amount of social

simulation have clear affinities to multi-agent systems (MAS) research on artificial societies. They differ in a

number of key respects, however, due to a mixture of pragmatic game-design considerations and their typically

strong embeddedness in narrative arcs, resulting in many important aspects of moral systems being represented

using explicitly scripted scenarios rather than through agent-based simulations. In this position paper, we

argue that these similarities and differences make RPGs a promising challenge domain for MAS research,

highlighting features such as moral dilemmas situated in more organic settings than seen in game-theoretic

models of social dilemmas, and heterogeneous representations of morality that use both moral calculus systems

and social simulation. We illustrate some possible approaches using a case study of the morality systems in

the game The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion.

1 INTRODUCTION

Role-playing games (RPGs) are a genre of videogame

in which the player takes on the role of a character

or group of characters and plays out a story in a vir-

tual world. The story often takes the form of a series

of quests intermixed with more free-form exploration;

the virtual world is typically populated by a number

of computer-controlled characters referred to as non-

player characters (NPCs).

1

A common and often prominent feature of RPG

design is the presence of a morality system of some

kind. These vary greatly in how they represent moral-

ity computationally, but in keeping with the high-

fantasy setting of many RPGs, often position char-

acters on a good vs. evil scale. Common features

include: updating characters’ morality as a result of

actions in the game world (killing someone innocent

1

There are also tabletop and live-action role-playing

games, but we limit ourselves here to the videogame genre,

especially to the subset sometimes called computer role-

playing games or CRPGs (Barton, 2008).

makes you more evil); modifying gameplay based on

moral alignment (an evil character is shunned or re-

acted to in a hostile manner); and modifying narrative

based on moral alignment (different choices result in

different endings). In some games this can have an

added layer of simulated social complexity, with dif-

ferent groups of NPCs or even individual NPCs mak-

ing their own moral judgments, instead of characters

falling on a universal good/evil alignment.

In addition to forming a core part of the game

mechanics of many RPGs, these representations of

morality can be used to pose dilemmas in which the

player must choose a course of action (Zagal, 2009;

Sicart, 2013). Such dilemmas can be analyzed from

both an “internal ludic” perspective, i.e. in terms of

the game world’s internal representation of morality,

or from an “externalized” perspective, i.e. in terms of

how the dilemma causes the player to reflect on moral

issues in the real world (Heron and Belford, 2014b).

The position we argue in this paper is that the

morality systems designed into role-playing games

are a productive setting for investigating simulated

244

Casas-Roma, J., Nelson, M., Arnedo-Moreno, J., Gaudl, S. and Saunders, R.

Towards Simulated Morality Systems: Role-Playing Games as Artificial Societies.

DOI: 10.5220/0007496702440251

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2019), pages 244-251

ISBN: 978-989-758-350-6

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

morality using multi-agent systems (MAS). We mean

this in two directions: that RPGs are a promising

testbed for MAS theories and architectures, and that

RPGs can serve as a potential application domain for

MAS research.

From the description above, it may even sound

like RPGs essentially already have simulations of

morality in artificial societies. A morality system plus

a world populated by NPCs is not too far off the mark

conceptually. However, in practice, RPGs and their

morality systems are designed and implemented in

quite a different manner from the way agents are mod-

eled and studied in MAS research. Videogame de-

signers approach the topic from a pragmatic perspec-

tive, since their goal is to make an entertaining and

coherent experience, and are not necessarily focused

on whether the simulation would make sense from a

scientific or philosophical perspective.

As a result of game designers’ understandable fo-

cus on experience design, NPCs are not usually im-

plemented using agent models from artificial intel-

ligence research, but in simpler architectures with a

good deal more scope for manual specification and

tweaking of behaviors. Moral dilemmas in particu-

lar are usually quite carefully scripted, set up by the

game’s narrative designer, using techniques such as

explicit branching-narrative choice points. Dilemmas

often do involve NPCs that could be seen as agents,

however, and in some cases these agents have an in-

teresting level of social simulation, especially simu-

lation of features such as reputation, i.e. what beliefs

NPCs hold about the player and how the player’s ac-

tions affect those beliefs (Russell, 2006).

In relation to ethical theories, videogames offer-

ing moral choices are usually based on a short-term

consequentialist approach: the moral alignment of the

choices is clear in advance, and the consequences are

foreseen and direct. However, and as Sicart (2013)

points out, games such as Fallout 3 often present the

player with choices that have no clear good or bad

options, and which often have unforeseeable conse-

quences in the long term. In this sense, and quoting

the definition of the Fallout series’ “karma” measure

in Multiple Authors (2005), the morality system in

a game involving this kind of morally-grey choices

measure “not only the effects of your actions but also

your intentions”. As a notorious example of a game

based on a quite different approach, Ultima IV is

based on virtue ethics; as pointed out by Heron and

Belford (2014a), the game requires the player to get

involved in moral reflection regarding their actions.

The modeling of ethical theories in artificial

agents is key in the field of artificial morality, and

Allen and Wallach (2005) provide an overview of dif-

ferent approaches. Whereas consequentialist or de-

ontological approaches seem to be a good fit for ar-

tificial moral agents (although not devoid of chal-

lenges), accounting for a Kantian or intentionalist ap-

proach faces the issue of accessing the agent’s mo-

tives, which some authors argue that an artificial agent

may not even have (Floridi and Sanders, 2004; Wal-

lach and Allen, 2010). In contrast, Muntean and

Howard (2014) suggest to build an artificial moral

agent based on virtue ethics by using genetic algo-

rithms.

It is possible to treat role-playing games more

fully as multi-agent systems, viewing a game’s NPCs

as a group of simulated agents and the player as a par-

ticipant in the agent society, along the lines of what

Guyot and Honiden (2006) call multi-agent participa-

tory simulations. Using this perspective, we propose

a research path for scaling the agent-based study of

moral systems to the kinds of dilemmas encountered

in role-playing games, which we argue pose both an

interesting challenge and promising domain for sim-

ulation of morality in artificial societies. To make our

argument more concrete, we analyze the morality sys-

tem implemented in the RPG The Elder Scrolls IV:

Oblivion from a MAS perspective.

2 RELATED WORK

There is a good deal of related work in both multi-

agent systems and games; we briefly summarize some

of the most relevant here.

There are a number of general proposals for using

games and game engines as test beds for multi-agent

systems research in various ways (Kaminka et al.,

2002; Bainbridge, 2007; Fabregues and Sierra, 2011;

Koeman et al., 2018; Juliani et al., 2018), as well

as more specific proposals arguing that role-playing

games have useful design principles to offer (Bar-

reteau et al., 2001; Guyot and Honiden, 2006).

One of the most relevant bodies of work on the

MAS side is that which uses multi-agent systems as

an empirical social-science tool to study social dilem-

mas, usually modeled by game-theory-style games

such as the prisoner’s dilemma (see Gotts et al., 2003,

for an extensive survey). Social dilemmas need not

necessarily have a moral interpretation, but often can

easily be read in such terms. Work on the role of

norms as a way of structuring behavior in agent so-

cieties approaches a similar problem with a different

conceptual framework (Boella et al., 2006).

Social simulation research has also studied this

issue, designing multi-agent systems to recreate and

study the behavior of artificial societies formed by ar-

Towards Simulated Morality Systems: Role-Playing Games as Artificial Societies

245

tificial agents. Different experiments study different

properties of such societies, such as the emergence

of altruistic behavior. Surveying such research, one

of the recommendations of Sullins (2005) is: “I think

that the agent-based approach is the correct one but

that the technology we have today is a bit too weak to

simulate the evolution of morality in full. To achieve

this goal will require software agents that have at least

some cognitive capacities”.

Our proposal is that role-playing games as a chal-

lenge domain pose questions about how to scale up

this type of multi-agent systems research to a set-

ting that has features not found in simpler game-

theoric games and more “flat” simulations. For ex-

ample: sequences of heterogeneous events over time,

taking place in various locations with a variety of

types of agents, situated within larger-scale narratives

that structure behavior and interpretation of behav-

ior. Nonetheless, RPGs do retain some advantages for

computational investigation, since they are still self-

contained virtual worlds.

From the game-research side, there is recent work

on social-simulation systems for games, which aims

to build frameworks in which games with multiple

NPCs can be designed more heavily around simu-

lation and agent-based (instead of scripted) ways of

representing social interactions (McCoy et al., 2011;

Samuel et al., 2015; Guimaraes et al., 2017). This

work doesn’t usually frame itself as representing

morality, but as with agent-based social-simulation

work, such architectures are likely to be quite appli-

cable to the case of morality systems as well.

3 GAMES AND ARTIFICIAL

AGENTS

Following the line set by those previously cited works

that push forward in the direction of considering vir-

tual worlds in videogames as complex simulations,

there are two main topics in which researchers in

MAS could benefit from the latest advances in such

games, as well as the other way around.

3.1 Dilemmas and Games

The field of game theory studies the behavior of mul-

tiple agents with regards to a set of decisions that of-

ten involve some notion of positive or negative pay-

offs. Although these studies are meant to be used

to predict the behavior that real-world agents would

have in a similar situation, they often assume that the

participants are perfect rational agents, meaning that

their decisions will always correspond to their best

possible choice in terms of outcomes; needless to say,

in real-world case scenarios the actual agents are of-

ten not as rational as one would like them to be, and

the situations are often more complex and messier to

model. Even though studies such as those of Baltag

et al. (2009) aim to cover this gap, there is still a sig-

nificant gap between realistic modeling of societies

and game-theoretic social models.

In the case of the prisoner’s dilemma, the individ-

ually rational solution is to defect, even though it’s in

the players’ overall best interests to cooperate. Some

studies (Fehr and Fischbacher, 2003, e.g.) suggest

that in the case of human agents there is in fact a bias

towards cooperation. What makes this dilemma inter-

esting in relation to videogames is that there is a set of

titles belonging to the Zero Escape series (first devel-

oped by Spike Chunsoft, and later by Chime), such as

Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward, that include mod-

ified versions of the prisoner’s dilemma as one of the

core mechanics of their gameplay.

When videogames have adapted the prisoner’s

dilemma as a gameplay mechanic, their participants

are explicitly not meant to be neutral, fully-rational

agents, but rather complex characters with different

personality traits, goals and motivations that greatly

affect how the dilemma should be faced. In this

case, the approach of such videogames to the clas-

sic dilemma opens up a new dimension that goes be-

yond the notions of rationality (in addition to being

less symmetric, as agents are no longer assumed to be

equivalent) and which demands a more “organic” ap-

proach that takes into account character traits, goals

and moral values of the particular agents involved in

it. These examples are based on scripted narratives

and do not properly belong to the RPG genre, but

they already begin to illustrate some of the features

that videogame versions of moral dilemmas typically

add, such as consideration of differing goals, values

and characters’ relationships into any evaluation, and

which may be of interest for research in MAS.

Along a similar line, experiments using the well-

known trolley problem (as in Foot (1978), among

many others), which is often framed as a dilemma

for the utilitarian ethical system, suggests that ratio-

nal notions of the greatest good for the greatest num-

ber are usually not enough to reach a consensus re-

garding the right choice. This particular dilemma has

become particularly relevant lately due to the grow-

ing advancements in self-driving vehicles. Awad et al.

(2018) conducted a survey study on a wide number of

human participants to determine how the particulari-

ties of the agents involved in the dilemma affect the

way people choose the preferred solution. The study

illustrates how a great deal of factors, such as the age,

ICAART 2019 - 11th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

246

gender, profession or background of the subjects in-

volved affect decisions. These effects, therefore, are

not based on a rational, game-theoretic reasoning, but

rather on other factors such as feelings, values and

prejudices. Drawing an analogy with the prisoner’s

dilemma case, we argue that a study of such cases us-

ing simulations including deeper and more complex

agents, such as those modeled in RPGs, can be ben-

eficial for understanding all the dimensions involved

in making a decision on this kind of scenario.

3.2 Artificial Societies and Games

A purpose of simulated artificial societies is to model

fundamental qualities of living systems through com-

puter models based on agents. These computer mod-

els can be used to study emergent behaviors among

the agents inhabiting an artificial society. Sugarscape,

for instance, was used to study the emergence of

social groups through interactions between simple

agents and their environment (Epstein and Axtell,

1996). Although this experiment starts with very sim-

ple grounding rules, the model showed the emergence

of certain interesting behaviors, such as group migra-

tion behaviors, or the formation of different “tribes”

that would compete for the dominance of particularly

resource-rich areas.

Other models, such as the one created by Pepper

and Smuts (2000), explore the emergence of altruis-

tic behavior and group formation. Furthermore, the

NEW TIES Project aimed to model an artificial en-

vironment in which artificial agents could evolve lan-

guage, society and even some understanding of their

own existence (Eiben et al., 2008). Although it was

not intended in the project, Sullins (2005) argues that

a complex model such as this one could be used to

study the emergence of morality in a social environ-

ment.

The computational study of emergent behavior in

social dynamics, nevertheless, often is based on sim-

ulating artificial societies formed by agents fulfilling

a restricted set of roles—precisely because the inter-

est in most of those works is to study the emergence

of behaviors that are not initially modeled within the

agents or the environment. Such restrictions, by de-

sign, do not account for more organic forms of social

relationships, e.g., moral judgments, or even for the

particular roles of certain agents in building and main-

taining those artificial societies. These kind of rela-

tionships would need to take into account things such

as the affinity that agents have towards each other,

their unique attributes as individual agents, and the

set of possible actions they can enact in their artificial

society.

Conversely, videogames often present the player

with a highly interactive virtual world in which agents

inhabiting them show compelling and complex be-

haviors and contribute towards depicting a believable

human-like society, though these systems are often

designed top-down rather than simulated bottom-up,

i.e. with directly represented high-level structure in-

stead of emergent structure. As the technologies be-

hind games have grown more and more powerful,

those virtual worlds have nonetheless begun to ac-

count for complex behaviors of their inhabitants such

as their day and night schedules, needs (such as eating

or sleeping), goals, and similar high-level features of

human agency: some of those virtual worlds are pop-

ulated by agents that wake up in the morning, eat, go

to work, socialize in a tavern, go back to sleep and

who, under certain conditions, may even decide to

disobey the law in order to fulfill some of their needs

(see “Responsibility” in Multiple Authors, 2008).

Even though any simulated aspects of virtual

worlds in videogames aim, ultimately, at the enter-

tainment of the player rather than at simulational fi-

delity, the level of detail in which their inhabitants are

created represents a valuable step forward in terms

of modeling agents that are part of a virtual society.

Considering this, we argue that researchers in MAS

can benefit from considering some of the richest cases

of artificial societies currently existing in videogames

and more specifically in some RPGs.

Titles based on a sandbox style of virtual world

provide a bridge that is closer to MAS work, while il-

lustrating some of the videogame features elaborated

in RPGs. One well-known example is Lionhead’s

Black & White (Molyneux, 2001), which implements

a simulation of moral choices and the emergence of

moral values as the game’s core mechanic. The player

assumes the role of a god in a newly created world,

populated initially by simple agents living in there.

As a god, the player’s influence over the world is me-

diated through the use of powers to shape the terrain

or affect the weather as well as through a kind of emis-

sary, which takes the form of a giant creature that also

roams around the world. That creature has its own

needs as well, and may decide, when it feels hungry,

to eat one of the inhabitants from the world. As its

master, the player can decide to either punish or re-

ward such behavior, thus reinforcing the creature to

do it again, or preventing it from repeating such ac-

tion. The feedback given by the player contributes to

the evolution not only of the moral profile of the emis-

sary, but also of the way the inhabitants in the world

are going to regard the player: if the player is helpful

and kind, their inhabitants will pay their respects and

love both the emissary and the player; if the player is

Towards Simulated Morality Systems: Role-Playing Games as Artificial Societies

247

a merciless, evil god, the inhabitants will fear them

both. In this case, both the emergence of a moral

system in a particular agent (the emissary) and their

effects on a society are the driving mechanics of the

game, which reinforces the claim that, nowadays, cer-

tain open-world games depicting complex societies

can be of great interest for the computational study

of moral emergence.

Another example can be found in the game se-

ries Creatures by Mindscape Inc. (Grand and Cliff,

1998), where the player assumes a similar role to the

god in Black & White, but selectively breeds creatures

in a closed habitat, to foster certain traits. Similar to

Black & White, creatures can be trained using rein-

forcement, but because there are multiple intelligent

agents acting and interacting in Creatures, players can

reward or punish social interaction between agents.

Creatures moves closer to artificial life (ALife) sim-

ulation, as the game does not feature a story-driven

plot, but acts more like a virtual fishtank or ant colony,

where the player entertains him or herself through ob-

serving changes in the environment and agents.

The evolution of agents in games is limited, and

the ways used to govern how agents behave varies; in

the case of Black & White, the inhabitants are con-

trolled by a scripted system, while the player’s emis-

sary is controlled by a neural network. For Creatures,

the agents are controlled by a rule-based system and

they evolve through breeding artificial chromosomes.

Even if some features of these agents are restricted

due to performance constraints for the game, we be-

lieve that, with relatively few additions, virtual worlds

such as these may be useful to study the evolution

of moral behaviors in an artificial society, and there-

fore we claim that this approach can lead to interest-

ing contributions to both the MAS and the soft AL-

ife fields. The best examples of fully realized moral-

ity systems in videogames, however, can be found in

RPGs, which we’ll turn to now.

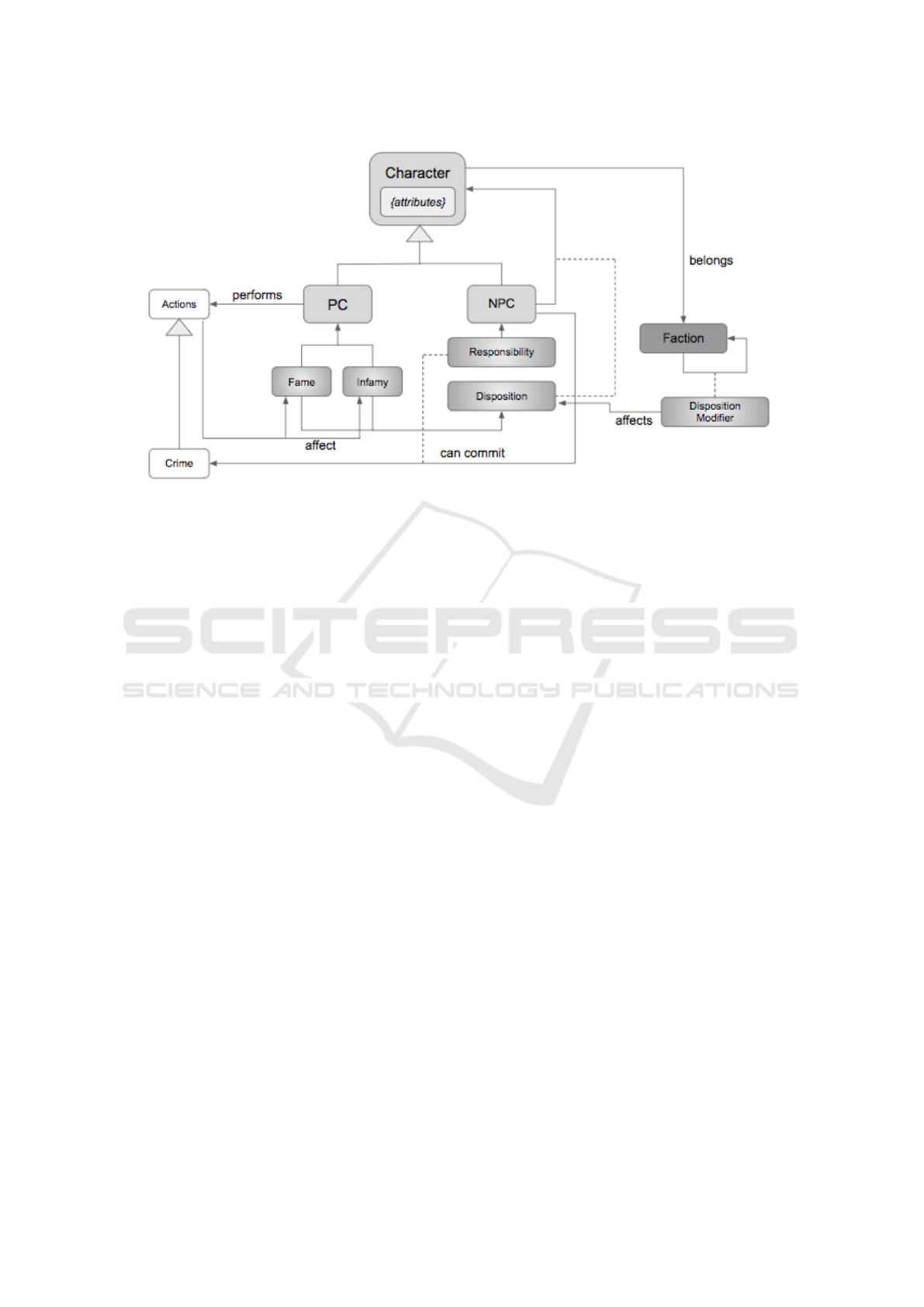

4 CASE STUDY: OBLIVION

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion (called just Oblivion

henceforth) is a computer RPG that takes place within

a richly simulated social and cultural world (Cham-

pion, 2009). Its social world simulation combined

with frequent references to moral aspects of actions

presents one of the more complex existing cases of

a game morality system with a strong role for virtual

agents in forming and enacting moral judgments. Fig-

ure 1 summarizes key elements of the game’s moral-

ity system, which we’ve produced as part of a larger

research project analyzing how different RPGs imple-

ment morality systems.

2

Even though the game is still mainly focused on

the players’ experience, and so the Player Character

(PC) takes a more relevant role in the model, we can

see how the NPCs are still related through all other

agents via a Disposition attribute that accounts for

how their relationship is. This disposition, in case of

the relationship between the PC and the NPCs, is af-

fected by the overall measurement of the PC’s “good”

and “bad” deeds, which are represented through the

Fame and Infamy properties. Aside from those, both

the NPCs and the PC have different attributes detail-

ing not only their physical and psychical strengths and

weaknesses, but also detailing a set of skills in which

they are proficient. This, in turn, determines what

kind of activities each NPC can carry out in the game,

and which it cannot. Furthermore, we can also see in

the model how allegiance to certain factions or social

groups is also taken into account when determining

the affinity between agents.

One of the more unique features of the way Obliv-

ion models NPCs, and which is particularly relevant

when considering morality in artificial societies, is

the attribute of Responsibility. In short, this attribute

represents how the NPC feels towards the existing

law in the virtual world. Unlike many other RPG

games with complex NPCs, Oblivion goes one step

beyond and allows NPCs with low responsibility to

(non-scriptedly) choose goal achievement over law-

fulness. For example, if an NPC has a low responsi-

bility score, needs food, and currently lacks anything

to eat, it may steal it from a market stall. This dif-

fers from many games, in which only the player and

specifically scripted “evil” characters have the pos-

sibility to violate norms in a way that the in-game

morality system would judge as a violation, which it

a step closer towards a simulation of moral calculus

and behavior in an agent society.

In fact, not only will NPCs in Oblivion make such

decisions regardless of whether the player could no-

tice the behavior or not, but if they do commit im-

moral acts, they risk facing the same consequences

as the PC would, if they are caught while committing

a crime by a guard or by another NPC. In particu-

lar, if the NPC is caught while committing a crime,

the guards will give it a chance to pay a bounty; if

the NPC cannot afford it (which it normally will not

be able to), then the guards will execute the NPC.

The NPC’s responsibility is also taken into account

when determining whether, when witnessing an ille-

gal activity, one NPC will care enough to report the

other one to the guards; NPCs with low responsibil-

2

We’ve gathered some details of how Oblivion is imple-

mented from the UESP wiki (Multiple Authors, 2008).

ICAART 2019 - 11th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

248

Figure 1: Diagram summarizing the operation of the morality systems in The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, viewed from an

agent-centric perspective.

ity, for instance, will not be bothered when witnessing

a crime, while NPCs with high responsibility will im-

mediately call the guards, or even confront the crimi-

nal.

So, as it currently is, Oblivion models a virtual

society with virtual agents that account for:

1. Day and night schedules and plans, with particular

goals and needs.

2. Different physical and psychical attributes.

3. Different sets of skills that allow them to engage

in some activities, while limiting others.

4. Their responsibility towards the virtual society’s

laws, which affect their reaction to illegal activi-

ties, as well as allowing them to engage in those.

5. A disposition attribute modeling a distinct rela-

tionship with every other artificial agent.

6. A social dimension accounting for the NPC be-

longing to particular groups or factions, which po-

tentially affect their relationship with NPCs from

other factions.

The major difference in this case, regarding its re-

lation to MAS, lies in the fact that the game is player-

centered: therefore, and even though NPCs show a

great deal of complexity in their model and behav-

ior, their properties are only dynamic in terms of their

relationship towards the player. In other words, al-

though each NPC has a disposition value towards

each other, or a responsibility value on their own,

those properties do not change over time: the disposi-

tion of an NPC only varies in its relationship towards

the PC, and the NPC’s responsibility is set right from

the beginning, meaning that the moral behavior of the

NPC is constant throughout the game, without the

possibility of changing. Similarly, and even though

the PC accounts for the Fame and Infamy derived

from performing morally good or morally bad deeds,

NPCs do not have such scales. However, the model

could be easily adapted to account for that in the same

way it already does for the PC’s case. This makes

sense when considering that this particular model, in

the end, is a means to provide a believable environ-

ment for a single-player game experience.

Nevertheless, we argue that this model of NPCs,

taking into account the complexity of their attributes,

their relationship with each other and their moral pro-

files, could very well be used to simulate a virtual

world populated by virtual agents accounting for all

those properties in a dynamic way, thus being able to

evolve and adapt to their interactions. Furthermore,

the fact that NPCs already have a particular skill set in

the current model would allow to account for different

roles that different agents could play or different con-

tributions they could make in the creation and evolu-

tion of the virtual society. This could be used both to

simulate a “self-driving” artificial society, populated

only by NPCs following their own behaviors, or to

keep the figure of the player involved in this artificial

society as a participant in the agent society, as Guyot

and Honiden (2006) propose. By allowing the artifi-

cial agents to evolve and adapt, the model represented

in this game can be used to create more organic ar-

tificial societies that could be used both to study the

Towards Simulated Morality Systems: Role-Playing Games as Artificial Societies

249

emergence of moral behaviors by MAS researchers,

and to simulate worlds exhibiting a greater level of

detail in terms of social dynamics for RPGs.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Role-playing games offer a novel view on artificial

morality in simulated societies situated in rich envi-

ronments. They often feature designed morality sys-

tems that have enough parallels to multi-agent sys-

tems work to make borrowing of techniques in both

directions plausible (and, we argue, promising), but

also differ in enough ways to pose research chal-

lenges. A few differences include the interplay of

character-level simulation and god’s-eye moral calcu-

lus, and especially the way that both of these simu-

lated elements are combined with pre-scripted com-

ponents and manually designed moral dilemmas that

designers use to capture aspects that they find diffi-

cult to do through a fully agent-based approach. In

general, one could characterize RPGs as a more het-

erogeneous and “messy” domain than those studied in

scientific agent-based research. They therefore pro-

vide a complex and interesting challenge domain for

research on multi-agent systems.

We have argued how cross-disciplinary research

in the areas of MAS and artificial societies using

RPGs can be greatly beneficial for future projects on

morality, both when studied as particular dilemma-

like cases and for their emergent behaviors in social

simulations. MAS can benefit from the organic set-

ting of dilemmas that videogames can offer; artificial

society research can benefit from complex and more

dynamic models of agents that are often depicted in

RPGs. At the same time, the complex worlds and so-

cial settings simulated in RPGs can benefit from ad-

vances in modeling emergent social behaviors in arti-

ficial societies to achieve greater levels of immersion.

Finally, we hope that our analysis of a particular case

study, the morality system of The Elder Scrolls IV:

Oblivion, has illustrated some possible directions for

combining the kind of modeling and systems design

done in RPGs with work in artificial societies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is funded by EC FP7 grant 621403

(ERA Chair: Games Research Opportunities) and

the Spanish Government through projects CO-

PRIVACY (TIN2011-27076-C03-02) and SMART-

GLACIS (TIN2014-57364-C2-2-R).

REFERENCES

Allen, C.; Smit, I. and Wallach, W. (2005). Artificial moral-

ity: Top-down, bottom-up, and hybrid approaches.

Ethics and Information Technology, 7(3):149–155.

Awad, E. et al. (2018). The moral machine experiment. Na-

ture, 583:59–64.

Bainbridge, W. S. (2007). The scientific research potential

of virtual worlds. Science, 317(5837):472–476.

Baltag, A., Smets, S., and Zvesper, J. A. (2009). Keep ‘hop-

ing’ for rationality: a solution to the backward induc-

tion paradox. Synthese, 169:301–333.

Barreteau, O., Bousquet, F., and Attonaty, J.-M. (2001).

Role-playing games for opening the black box of

multi-agent systems: Method and lessons of its appli-

cation to Senegal River Valley irrigated systems. Jour-

nal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 4(2).

Barton, M. (2008). Dungeons and Desktops: The History

of Computer Role-Playing Games. A K Peters.

Boella, G., Van Der Torre, L., and Verhagen, H. (2006). In-

troduction to normative multiagent systems. Compu-

tational & Mathematical Organization Theory, 12(2-

3):71–79.

Champion, E. (2009). Roles and worlds in the hybrid RPG

game of Oblivion. International Journal of Role-

Playing, 1:37–52.

Eiben, A. E. et al. (2008). NEW TIES project final re-

port. https://cordis.europa.eu/publication/rcn/10221

en.html.

Epstein, J. M. and Axtell, R. (1996). Growing Artificial

Societies: Social Science from the Bottom Up. MIT

Press, Cambridge.

Fabregues, A. and Sierra, C. (2011). DipGame: A challeng-

ing negotiation testbed. Engineering Applications of

Artificial Intelligence, 24(7):1137–1146.

Fehr, E. and Fischbacher, U. (2003). The nature of human

altruism. Nature, 425:785–791.

Floridi, L. and Sanders, J. W. (2004). On the morality of

artificial agents. Minds and Machines, 14(3):349–379.

Foot, P. (1978). The problem of abortion and the doctrine

of the double effect. In Virtues and Vices and Other

Essays in Moral Philosophy. Blackwell.

Gotts, N. M., Polhill, J. G., and Law, A. N. R. (2003).

Agent-based simulation in the study of social dilem-

mas. Artificial Intelligence Review, 19(1):3–92.

Grand, S. and Cliff, D. (1998). Creatures: Entertain-

ment software agents with artificial life. Autonomous

Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, 1(1):39–57.

Guimaraes, M., Santos, P., and Jhala, A. (2017). CiF-CK:

An architecture for social NPCs in commercial games.

In IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence

and Games, pages 126–133.

Guyot, P. and Honiden, S. (2006). Agent-based partici-

patory simulations: Merging multi-agent systems and

role-playing games. Journal of Artificial Societies and

Social Simulation, 9(4).

Heron, M. and Belford, P. (2014a). ‘It’s only a game’ —

ethics, empathy and identification in game morality

systems. The Computer Games Journal, 3(1):34–53.

ICAART 2019 - 11th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

250

Heron, M. J. and Belford, P. H. (2014b). Do you feel like a

hero yet? Externalized morality in video games. Jour-

nal of Games Criticism, 1(2).

Juliani, A., Berges, V.-P., Vckay, E., Gao, Y., Henry, H.,

Mattar, M., and Lange, D. (2018). Unity: A gen-

eral platform for intelligent agents. arXiv:1809.02627

(preprint).

Kaminka, G. A., Veloso, M. M., Schaffer, S., Sollitto, C.,

Adobbati, R., Marshall, A. N., Scholer, A., and Te-

jada, S. (2002). Gamebots: A flexible test bed for mul-

tiagent team research. Communications of the ACM,

45(1):43–45.

Koeman, V. J., Griffioen, H. J., Plenge, D. C., and Hin-

driks, K. V. (2018). StarCraft as a testbed for engineer-

ing complex distributed systems using cognitive agent

technology. In Proceedings of the International Con-

ference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Sys-

tems, pages 1983–1985.

McCoy, J., Treanor, M., Samuel, B., Mateas, M., and

Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2011). Prom Week: Social physics

as gameplay. In Proceedings of the International Con-

ference on the Foundations of Digital Games, pages

319–321.

Molyneux, P. (2001). Postmortem: Lionhead Studios’

Black & White. Game Developer. Reprinted in: Post-

mortems from Game Developer, CMP Books, 2003,

pages 151–160.

Multiple Authors (2005). Fallout wiki (Nukapedia):

Karma. http://fallout.wikia.com/wiki/Karma. Ac-

cessed: 2018-12-24.

Multiple Authors (2008). The unofficial Elder Scrolls pages

(UESP): Oblivion. https://en.uesp.net/wiki/Oblivion:

Oblivion. Accessed: 2018-11-15.

Muntean, I. and Howard, D. (2014). Artificial moral agents:

Creative, autonomous, social. An approach based on

evolutionary computation. In Sociable Robots and

the Future of Social Relations: Proceedings of Robo-

Philosophy 2014, pages 217–230.

Pepper, J. W. and Smuts, B. B. (2000). The evolution

of cooperation in an ecological context: An agent-

based model. In Kohler, T. A. and Gumerman, G. J.,

editors, Dynamics in Human and Primate Societies:

Agent-Based Modeling of Social and Spatial Pro-

cesses, pages 45–76. Oxford University Press.

Russell, A. (2006). Opinion systems. In AI Game Program-

ming Wisdom 3. Charles River Media.

Samuel, B., Reed, A. A., Maddaloni, P., Mateas, M., and

Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2015). The Ensemble Engine:

Next-generation social physics. In Proceedings of the

International Conference on the Foundations of Digi-

tal Games, pages 22–25.

Sicart, M. (2013). Moral dilemmas in computer games. De-

sign Issues, 29(3):28–37.

Sullins, J. P. (2005). Ethics and artificial life: From model-

ing to moral agents. Ethics and Information Technol-

ogy, 7(139).

Wallach, W., F. S. and Allen, C. (2010). A conceptual and

computational model of moral decision making in hu-

man and artificial agents. Topics in Cognitive Science,

2(3):454–485.

Zagal, J. (2009). Ethically notable videogames: Moral

dilemmas and gameplay. In Proceedings of the 2009

DiGRA Conference.

Towards Simulated Morality Systems: Role-Playing Games as Artificial Societies

251