Academic Achievement Reflected the Quality of Life and

Neurocognitive Status in Malaysian Primary School Children

Gisely Vionalita

1

, I. Zalina

2

and W. A. Asim

2

1

Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Universitas Esa Unggul, Jakarta

2

BRAINetwork Centre for Neurocognitive Sciences, School of Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia,

Kubang Kerian Kelantan 16150

Keywords: CANTAB, primary school children, cognitive status, academic achievement.

Abstract: Academic achievement is not the only indicator of achievement in school. The neurocognitive profile, as

measured by the quality of life (QoL) and neurocognitive status are important markers that make academic

achievement more relevant about optimum brain utilization. The main objective of this study was to

determine the relationship between quality of life, neurocognitive status and academic achievement in a

sample of children in a Malaysian primary school. QoL was measured using three versions of the TNO-AZL

quality of life (TACQOL) questionnaire from the children’s (CV), parents’ (PV) and teachers’ (TV)

perspectives. Neurocognitive status was assessed in two domains, executive function and visual memory

using Cambridge Neuropsychology Tests Automated Battery (CANTAB

®

). A convenience sampling was

undertaken for all 95 Standard One Zainab 2 Primary School children (7 Years Old), 95 parents and 4

teachers. Regarding executive function, 42.1% of children experienced difficulties in an extra dimensional

shift which measures attention flexibility in accepting a new rule. However, they performed well in

theintraextra dimensional shift, indicating that most children responded positively to experiential learning.

For visual memory, 49.5% of children experienced some difficulties regarding their short term visual

memory. The relationship between QoL, neurocognitive status and academic achievement of the children

showed that only ‘cognitive complaint’ and ‘negative mood’ had a significant linear positive relationship

with academic achievement. Thus, this study has shown that academic achievement does not necessarily

reflect the neurocognitive status of children implying that some neurocognitive problems remain undetected.

A more meaningful assessment of academic achievement, in primary schools, should include an assessment

of both QoL and neurocognitive profile.

1 INTRODUCTION

Current research indicates that contrary to previous

concepts which postulate that learning occurs at

specific periods of the developing brain, there is

evidence that both the developing and the mature

brain are structurally altered when learning occurs.

These structural changes are believed to encode the

learning process in the brain. Studies have found that

direct contact with a stimulating physical

environment and an interactive social group can alter

the structure of nerve cells and of the tissues that

support them (Breslow, 1999). The nerve cells

develop a greater number of synapses through which

they communicate with each other,and the structure

of the nerve cells themselves is correspondingly

altered.

Quality of life (QoL) is a multidimensional

construct referring to the subjective perception of

physical, mental, social, psychological and

functional aspects of well-being and health (Cella

and Tulsky, 1990; Felce and Perry, 1995; Hofstede,

1984). From an epidemiological point of view,

information on the quality of life is important to

define health problems and to evaluate the well-

being and functioning of populations (Bullinger et

al., 2008). Indeed, QoL conceptualised as the

individual’s self-evaluation of their health status is

an important criterion in evaluating health and health

care. Until now, few systematic attempts have been

made to develop instruments to assess the QoL of

children using such a conceptualisation (Vogels et

Vionalita, G., Zalina, I. and Asim, W.

Academic Achievement Reflected the Quality of Life and Neurocognitive Status in Malaysian Primary School Children.

DOI: 10.5220/0009950126632669

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Recent Innovations (ICRI 2018), pages 2663-2669

ISBN: 978-989-758-458-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2663

al., 2000). In this study the QoL is one of the

variables that will be used in the self-evaluationof

wellness and the tool chosen is the Netherlands

Organisation for Applied Scientific Research

Academic Medical Centre (TNO-AZL) child quality

of life (TACQOL) (Vogels et al., 1998; Kamphuis et

al., 1997; Kolsteren et al., 2001; Vogels et al., 1999;

Bernard et al., 2009) questionnaire. In this case, the

QoL, as assessed by the TACQOL, is defined as

children's health status, weighted by the emotional

response of their health status problems from

theirperspectives.

Indeed, children are the best source of

information concerning their feelings and

evaluations even though they may be lacking in their

vocabulary and reading skills. The TACQOL

considers this and has been designed with simple

language and can be completed in a short period.

TACQOL is a multidimensional instrument, with 7

subscales. The subscales covered by the TACQOL

are based on a review of the literature, discussions

with experts (child psychologists, paediatricians)

and statistical testing (Vogels et al., 2000). The

TACQOL was constructed to enable a systematic,

valid and reliable description of the quality of life of

children aged 6 till 15 by the children themselves or

their parents (Arnould et al., 2004).

In this study, the neurocognitive profiling and

the assessment of the neurocognitive status of

primary school children will focus on the executive

functions of the prefrontal cortex in relation to the

limbic system and how they impact on the academic

achievement and QoL of these children. The

neurocognitive evaluation of school children was

carried out using the Cambridge Neuropsychological

Tests Automated Battery (CANTAB

®

) (Luciana,

2003; Cognition, 2007; Sharma, 2013; Robbins et

al., 1994; Sahakian and Owen, 1992; De Luca et al.,

2003).These tests are comparable across cultures as

they have the advantage of being language-

independent and culture-free.

In this study, the CANTAB

®

was chosen for the

assessment of neurocognitive status as it allows for a

complete assessment of the neurocognitive profile

through an extensively validated neuropsychological

battery of tests. It is highly portable and uses a touch

screen computer system which can be easily applied

to all respondents. The CANTAB

®

consists of

several well-validated tests, each of which taps one

or more cognitive domains, and produces some

outcome variables. There are six domains which are

assessed in CANTAB

®

. In this study, two tests from

CANTAB

®

were used from two domains (executive

function and visual memory) which are closely

related to learning and memory. IED Intra-Extra

Dimensional Set Shift (IED) (Lukowski et al., 2010;

Lythe et al., 2005; Collinson et al., 2014) was used

to assess executive function of the children while

Paired Associates Learning (PAL) (de Rover et al.,

2011; O'Connell et al., 2004; Barnett et al., 2015)

was used to assess the visual memory of the

children.

IED is primarily sensitive to changes affecting

the frontostriatal areas of the brain. It is sensitive to

cognitive changes associated with visual

discrimination and attentional set formation

maintenance, shifting and flexibility of attention

(Heinzel et al., 2010).

The PAL (Paired Associates Learning) was

chosen from the CANTAB

®

as one of two tests that

were carried out in this study. PAL measures visual

memory,and it assesses episodic memory, new

learning and is sensitive to medial temporal lobe

functioning. Thus, in this study, PAL allowed for

the assessment of the learning of items (as syllables,

digits or words) in pairs so that one member of the

pair evokes recall of the other.

In the context of this study, academic

achievement is defined as the outcome of education

in the form of knowledge, skills and attitude, which

a student has achieved through attaining specific

educational goals. Examinations or continuous

assessment commonly measure academic

achievementbut there is no general agreement on

how it is best tested or which aspects are most

important. It is one of the indicators that can

describe the school-based performance of children.

2 RESEARCH METHOD

This cross-sectional study involved the observation

of all members of a population, at one specific point

in time. In this case, the study involved all Standard

One children (7 Years Old) of Zainab 2 Primary

School, Kota Bharu, Kelantan and included their

parents as well as teachers.

2.1 Quality of Life

Quality of life was assessed from primary data

obtained from a translated and validated TACQOL

questionnaire with three versions. A parent and

teacher version of the TACQOL questionnaire was

constructed for parents and teachers to assess the

quality of life of the children from their perspectives.

The TACQOL - Child Version (TACQOL-CV) was

constructed for children to assess themselves. The

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

2664

TACQOL – Parent/Teacher Version (TACQOL-

P/TV) specifically asked parents and teachers to

evaluate and assess the children’s feelings about

their physical, emotional and cognitive status. The

major difference between the versions (child, parent

and teacher) was regarding the perspective of the

questions asked. The parent and teacher

questionnaires used the following format: “has your

child had…. or did your child have…?”, while the

child questionnaire used the format: “have you had

…. or did you have…?”.

The English version of the TACQOL was

forward translated into Bahasa Malaysia and

subsequently back-translated into English. This

questionnaire had 56 items, with a Likert scale type

of assessment (never, occasionally, only within the

past weeks, often and always). The TACQOL

questionnaire covered seven subscales: physical

complaints and motor functioning (physical),

autonomous functioning (daily living), social

functioning (social), cognitive functioning and

positive moods and negative moods (Verrips et al.,

1999). All respondents were interviewed and

observed within the school setting using the

translated and validated questionnaire. Informed

consent was obtained from all respondents of the

study, following which the questionnaire was

completed by 95 Standard One children of Zainab 2

Primary School, Kota Bharu Kelantan, 95 parents of

the same children and 4 teachers who taught these

Standard One children.

2.2 Neurocognitive Status

Neurocognitive function was analysed from primary

data obtained from two tests: IED (Intra Extra

Dimensional Set Shift) and PAL (Paired Associates

Learning) from within the CANTAB

®

battery tests.

These two tests were sequentially administered to

the respondents by trained data collectors. The tests

were administered to 95 children in a conducive and

quiet place with minimal distractions. These tests

were completed within 20 minutes and were simple

to understand. The same instructor for both tests

supervised all the children.

The IED screened for executive function in nine

stages. Stage 1 started with two simple, colour-filled

shapes and required children to learn and touch the

correct stimuli to show simple discrimination

learning. In Stage 2, the contingencies were reversed

to show reversal learning. In Stage 3, the second

dimension was introduced, with shapes and lines

together as a distraction. The contingencies were not

changed in Stage 4 but included overlapping and

simple discrimination. Reversal learning occurs

again in Stage 5. New compound stimuli were

presented in Stage 6. Subjects were required to be

attentive to the previously relevant dimension of

shapes and learn which of the two exemplars were

correct. Stage 7 completed an interdimensional shift.

In Stage 8, children were required to shift attention

to the previously irrelevant dimension and learn

which of the two exemplars in this dimension were

now correct. Thisgave a good indication of

attentional flexibility. In Stage 9, the contingencies

were again reversed.

PAL screened the visual memory ability in 5

separate stages. The children were required to

remember the shapes displayed on the screen. The

test started with 1 shape and then progressed to 2

shapes, 3 shapes, 6 shapes and 8 shapes. For each

stage, boxes were displayed on the screen. All were

opened in a randomized order. Two or more of them

contained a pattern.

The patterns in the boxes were then displayed in

the middle of the screen, one at a time and the

subject was asked to touch the box where the pattern

was originally located.Each stage had up to ten

trials. If the subject made an error, the patterns were

presented to remind the subject of their locations.

When the subjects correctly identified allthe

locations, they proceeded to the next stage. If the

subject was unable to complete a stage correctly, the

test was terminated.

The CANTAB

®

battery of tests wascomputerized

and provided automatic results that were presented

based on the requested outcome measurement. From

the summary template definition, the researcher was

able to select the outcome measurement that was

required. The results were automatically calculated

within the datasheet format for further statistical

analysis. In this study, the outcome measurement for

executive function and visual memory were a

measure of the total errors.

2.3 Academic Achievement

Academic achievement was analyzed from

secondary data obtained from the school database of

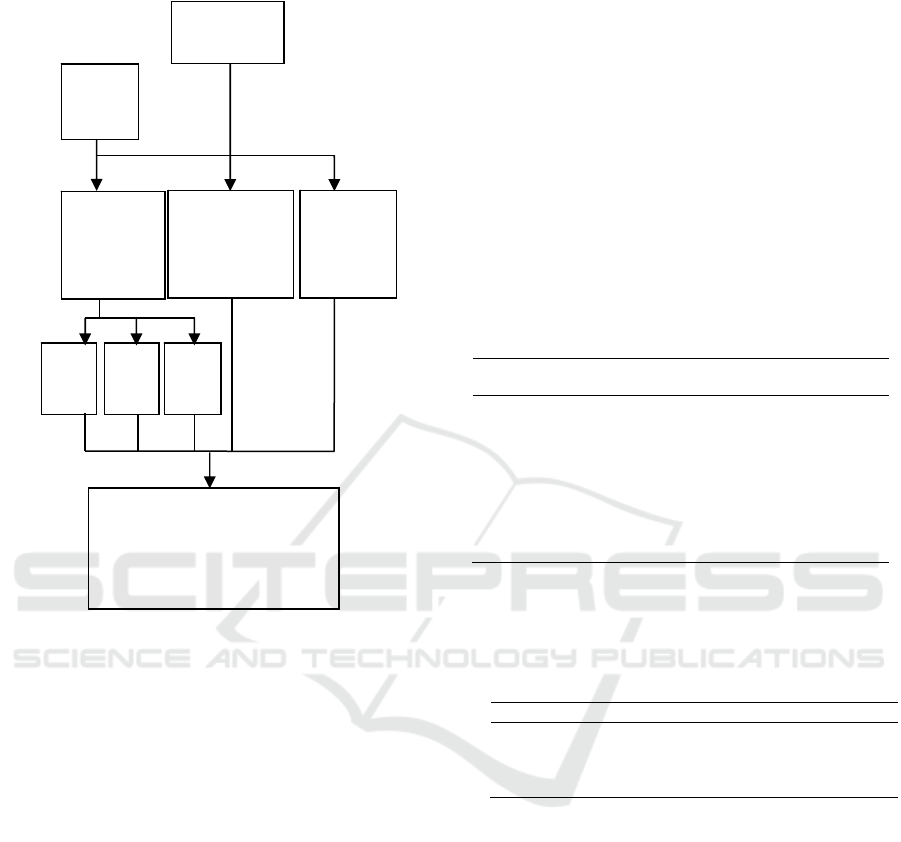

the Zainab 2 Primary School as shown in Figure 1.

The data was obtained from the average of mid-year

examination of 2011. The data provided information

on six subjects taught within the Standard One

school curriculum.

Academic Achievement Reflected the Quality of Life and Neurocognitive Status in Malaysian Primary School Children

2665

Figure 1: Research Framework

3 RESULTS

The average scores of the subscales in quality of life

assessments from children’s, parents’ and teachers’

perspectives together with a total error of both the

IED and PAL tests were assessedregarding their

relationship to the average academic achievement of

the Standard One children from Zainab 2 Primary

School. Simple linear regressions followed by

multiple linear regressionwere appliedtoanalyzing

the relationship between QoL, neurocognitive status

and academic achievement. As a requirement for

applying the multiple linear regression, simple linear

regression was applied first to check the significance

of the factors. From the simple linear regression for

univariable analysis, it was found that all the

variables were significant factorsfor academic

achievement (p<0.25) (Table 1). Following this, all

the variables were subjected to multiple linear

regression for variable selection. It was seen that

only ‘cognitive’ and ‘negative mood’ had a

significant linear relationship with academic

achievement (p<0.05) (Table2).

Multiple linear regression analysis showed a

significant linear positive relationship between both

cognitive and negative domains of the quality of life

assessment with the academic achievement. One

single improvement in cognitive problem increased

the academic achievement by a score of 0.78 and for

one single improvement in negative problem the

academic achievement improved by 1.27. However,

there was no significant linear relationship between

neurocognitive status and academic achievement,

indicating that the academic achievement does not

fully represent the neurocognitive status of the

children.

Table 1: Simple linear regression for variables

Variable b

a

(95% CI) P-

Value

Physical

Motor

Autonomy

Cognitive

Social

Positive Mood

Negative Mood

Total Error IED

Total Error PAL

0.78 (-0.22, 1.79)

0.68 (-0.40, 1.75)

1.01 (0.08, 1.94)

1.43 (0.85, 2.02)

0.99 (-0.15, 2.13)

0.77 (-0.15, 1.68)

1.91 (1.18, 2.64)

-0.16 (-0.36, 0.26)

-0.26 (-0.53, 0.02)

0.126

0.215

0.003

0.000

0.087

0.098

0.000

0.090

0.052

a

Crude regression coefficient

P-value significant at <0.25

Table 2: Relationship between variables with academic

achievement in Standard One children of Zainab 2

Primary School

Variable b

a

(95% CI) t-stat P-value

Cognitive

Negative

0.78 (0.03,

1.53)

1.27 (0.33,

2.22)

2.08

2.68

0.041

0.009

a

adjusted regression coefficient

b

P-value significant at <0.05

Forward multiple linear regression applied. Model

assumptions are fulfilled.There were no interactions

amongst independent variables. No multicollinearity

detected.

Coefficient of determination (R2) = 0.254

Final model equation

Academic achievement= 31.26 + 1.27 * Negative +

0.78 * Cognitive

Pare

nts’

pers

pect

Tea

cher

s’

pers

Chil

dren

’s

pers

Relationship between quality of life,

neurocognitive status and academic

achievement of Standard One

Malaysian primary school children

Assessmen

t of

academic

achieveme

nt

Assessment of

neurocognitive

status in

executive

function and

visual memory

StandardOne

Zainab 2

Primar

y

Comparison

of quality of

life using

translated

and

validated

Develo

ped

training

session

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

2666

4 DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to evaluate the

relationship between quality of life, neurocognitive

status and academic achievement. As mentioned

earlier, the average scores of the subscales in quality

of life assessments from children’s, parents’ and

teachers’ perspectives together with total error of

both the CANTAB

®

IED and CANTAB

®

PAL tests

were assessed in terms of their relationship to the

academic achievement of the Standard One Zainab 2

Primary School children.

From the statistical analysis, involving seven

subscales in QoL and two domains in

neurocognitive status, it was found that a significant

relationship existed between two subscales of the

QOL. Five other subscales were not significantly

related to academic achievement. Those five

subscales are physical, motor, autonomy, social and

positive moods. These findings correlate well with

De Oliveira Filho and Vieira (2007), where the

researchers were also unable to detect any

significant association between academic

performance and residents’ perceptions about their

subjective quality of life. These findings might

suggest that any knowledge gained, occurred

independently and was unrelated to how people

perceived their quality of life.

However, in contrast to the study done by De

Oliveira Filho and Vieira (2007), this study explored

the neurocognitive status of children, and it was

found that two subscales had a significant

relationship with academic achievement. These two

subscales were from the perspective of cognition and

negative moods. Both of these subscales are closely

related to perceptions of negativity and can thus be

linked to perceptions of the ability in catching up

with school-work and the frequency negative

feelings in children, both of which have been shown

in this study to be the main factors affecting the QoL

and at the same time is able to influence the

academic achievement.

Regarding the relationship between

neurocognitive status and academic achievement as

measured by the CANTAB

®

battery of tests, no

significant relationship was found between executive

function and the academic achievement of the

children as measured by their examination results.

Similarly, there was no statistically significant

relationship between visual memory and the

academic achievement in these children.

Executive function is one of the important

factors in learning, and with IED it is possible to

detect the ability of the children in

simplediscrimination, reversal learning and also

experiential learning. Those abilities are very useful

to improve the learning abilities of children.

Similarly, PAL is useful in the assessment of visual

memory,and any learning difficulties with visual

memory in young children will often lead to a

significant problem in both long-term and short-term

memory and difficulty in new learning. It also

affects a person’s ability to relearn appropriate

behaviour (Cusimano, 2001). However, there is no

association between both of the executive function

and visual memory with the academic achievement.

The main purpose of the current educational system

is to measurethe ability and success of students.

These measurements still do not reflect the

neurocognitive function of those children and some

problems with neurocognition remain undetected. In

Malaysia itself, the numbers of children with

learning disabilities have almost doubled over the

last three years period for primary school (473 to

656). This is an estimated increase of about 57% in

the number of programs for special education for

primary school level (Taib, 2008). In order to make

academic achievement more efficient, the education

system needs a neurocognitive profiling system that

includes all the information about the quality of life

and neurocognitive wellness from the

neurocognitive status of the children.

5 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, The fact that cognitive status of the

children has no correlation with the academic

achievement indicates that the school examination

for the Standard one children cannot represent the

cognitive ability regarding executive function and

the visual memory. It can be explained that the

academic achievement from the school still does not

reflect the neurocognitive status of those children

and some problems with neurocognition remain

undetected. This information about the cognitive

status of children is very important to improve the

education system. Thus, the neurocognitive status

can act as important indicators of a childs’ academic

achievement. This study will be expanded through

the perspective of the children about other domain in

cognitive status and its relation with their academic

achievement.

Academic Achievement Reflected the Quality of Life and Neurocognitive Status in Malaysian Primary School Children

2667

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by BRAINetwork Centre

for Neurocognitive Science School of Health

Universiti Sains Malaysia. The authors would like to

express their deepest gratitude to children and

teachers who participated in this study and the staff

at primary schools in SK Zainab 2 Kota Bharu,

Kelantan.

REFERENCES

Arnould, C., Penta, M., Renders, A., and Thonnard, J. L.

(2004). ABILHAND-Kids A measure of manual

ability in children with cerebral palsy. Neurology,

63(6): 1045-1052.

Barnett, J. H., Blackwell, A. D., Sahakian, B. J., &

Robbins, T. W. (2015). The paired associates learning

(PAL) test: 30 years of CANTAB translational

neuroscience from laboratory to bedside in dementia

research. In Translational Neuropsychopharmacology,

449-474. Springer, Cham.

Bernard, B. A., Stebbins, G. T., Siegel, S., Schultz, T. M.,

Hays, C., Morrissey, M. J., ... and Goetz, C. G. (2009).

Determinants of quality of life in children with Gilles

de la Tourette syndrome. Movement disorders, 24(7):

1070-1073.

Breslow, L. (1999). New research points to the importance

of using active learning in the classroom. TLL Library,

13 (1).

Bullinger, M., Brütt, A. L., Erhart, M., Ravens-Sieberer,

U., and BELLA Study Group. (2008). Psychometric

properties of the KINDL-R questionnaire: results of

the BELLA study. European child & adolescent

psychiatry, 17(1): 125-132.

Cella, D. F., and Tulsky, D. S. (1990). Measuring quality

of life today: methodological aspects. Oncology

(Williston Park, NY), 4(5): 29-38.

Cognition, C. (2007). Cambridge Neuropsychological

Tests Automated Battery (CANTAB), Eclipse Version.

Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Cognition.

Collinson, S. L., Tong, S. J., Loh, S. S., Chionh, S. B., and

Merchant, R. A. (2014). Midlife metabolic syndrome

and neurocognitive function in a mixed Asian sample.

International psychogeriatrics, 26(8): 1305-1316.

Cusimano, A. (2001). Learning Disabilities--there is a

Cure: A Guide for Parents, Educators, and

Physicians. Learning Disabilities.

De Luca, C. R., Wood, S. J., Anderson, V., Buchanan, J.

A., Proffitt, T. M., Mahony, K., and Pantelis, C.

(2003). Normative data from the CANTAB. I:

development of executive function over the lifespan.

Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology,

25(2): 242-254.

De Oliveira Filho, G. R., and Vieira, J. E. (2007). The

relationship of learning environment, quality of life,

and study strategies measures to anesthesiology

resident academic performance. Anesthesia &

Analgesia, 104(6): 1467-1472.

De Rover, M., Pironti, V. A., McCabe, J. A., Acosta-

Cabronero, J., Arana, F. S., Morein-Zamir, S., ... and

Sahakian, B. J. (2011). Hippocampal dysfunction in

patients with mild cognitive impairment: a functional

neuroimaging study of a visuospatial paired associates

learning task. Neuropsychologia, 49(7): 2060-2070.

Felce, D., and Perry, J. (1995). Quality of life: Its

definition and measurement. Research in

developmental disabilities, 16(1): 51-74.

Heinzel, A., Northoff, G., Boeker, H., Boesiger, P., and

Grimm, S. (2010). Emotional processing and

executive functions in major depressive disorder:

dorsal prefrontal activity correlates with performance

in the intra–extra dimensional set shift. Acta

neuropsychiatrica, 22(6): 269-279.

Hofstede, G. (1984). The cultural relativity of the quality

of life concept. Academy of Management review, 9(3):

389-398.

Kamphuis, R., Theunissen, N., & Witb, J. (1997). Short

communication health-related quality of life measure

for children-the TACQOL. J Appl Therapeut, 1: 357-

60.

Kolsteren, M. M., Koopman, H. M., Schalekamp, G., &

Mearin, M. L. (2001). Health-related quality of life in

children with celiac disease. The Journal of pediatrics,

138(4): 593-595.

Luciana, M. (2003). Practitioner review: computerized

assessment of neuropsychological function in children:

clinical and research applications of the Cambridge

Neuropsychological Testing Automated Battery

(CANTAB). Journal of Child Psychology and

Psychiatry, 44(5): 649-663.

Lukowski, A. F., Koss, M., Burden, M. J., Jonides, J.,

Nelson, C. A., Kaciroti, N., ... and Lozoff, B. (2010).

Iron deficiency in infancy and neurocognitive

functioning at 19 years: evidence of long-term deficits

in executive function and recognition memory.

Nutritional neuroscience, 13(2): 54-70.

Lythe, K. E., Anderson, I. M., Deakin, J. F. W., Elliott, R.,

and Strickland, P. L. (2005). Lack of behavioural

effects after acute tyrosine depletion in healthy

volunteers. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 19(1): 5-

11.

O'Connell, H., Coen, R., Kidd, N., Warsi, M., Chin, A. V.,

and Lawlor, B. A. (2004). Early detection of

Alzheimer's disease (AD) using the CANTAB paired

Associates Learning Test. International Journal of

Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(12): 1207-1208.

Robbins, T. W., James, M., Owen, A. M., Sahakian, B. J.,

McInnes, L., and Rabbitt, P. (1994). Cambridge

Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery

(CANTAB): a factor analytic study of a large sample

of normal elderly volunteers. Dementia and Geriatric

Cognitive Disorders, 5(5): 266-281.

Sahakian, B. J., and Owen, A. M. (1992). Computerized

assessment in neuropsychiatry using CANTAB:

discussion paper. Journal of the Royal Society of

Medicine, 85(7): 399.

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

2668

Sharma, A. (2013). Cambridge Neuropsychological Test

Automated Battery. In Encyclopedia of Autism

Spectrum Disorders, pp. 498-515. Springer, New

York, NY.

Taib, M. N. M. (2008). School management concerning

collaboration with social resources in community: Its’

approaches and problems. Primary and Middle Years

Educator, 6(2): 9-12.

Verrips, E. G. H., Vogels, T. G. C., Koopman, H. M.,

Theunissen, N. C. M., Kamphuis, R. O. B. P., Fekkes,

M., Wit, J. A. N. M. and Vanhorick, S. P. V. (1999).

Measuring health-related quality of life in a child

population. The European Journal of Public Health,

9(3):188-193.

Vogels, A. G. C., Bruill, J., Stuifbergen, M., Koopman, H.

M., and Verrips, G. H. W. (1999). Validity and

reliability of a generic health-related quality of life

instrument for adolescents, the TACQOL. Quality of

Life Research, 630-630.

Vogels, T., Verrips, G. H. W., Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P.,

Fekkes, M., Kamphuis, R. P., Koopman, H. M., ... and

Wit, J. M. (1998). Measuring health-related quality of

life in children: the development of the TACQOL

parent form. Quality of life research, 7(5): 457-465.

Vogels, T., Verrips, G. H. W., Koopman, H. M.,

Theunissen, N. C. M., Fekkes, M., & Kamphuis, R. P.

(2000). TACQOL manual: parent form and child form.

Leiden: Leiden Center for Child Health and Pediatrics

LUMC-TNO.

Academic Achievement Reflected the Quality of Life and Neurocognitive Status in Malaysian Primary School Children

2669