Too Broke for the Hype: Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Fashion

Products among Muslim Students

Defta Adiprima

1

, Kenny Devita Indraswari

1

and Rahmatina Awaliah Kasri

1

1

Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia

Keywords: Counterfeit, Fashion Product, Muslim Religiosity, Ethical Consciousness

Abstract: The growth in international trade of counterfeit fashion products poses a serious threat to the global

economic conditions. Producers may become unmotivated to be innovative because of counterfeiting which

could lead to stagnation and unfair competition in business. This threat cannot be separated from the

consumers their rationales behind their decision related to counterfeit products which is still unclear and

varies across society. This phenomenon became more interesting to be studied in Indonesia which has

strong Islamic culture. Therefore, this study intends to analyze the influential factors of purchase intention

towards counterfeit fashion products for Muslim consumers. Conceptual framework of this study

emphasizes several beliefs namely value consciousness, social risk, performance risk, subjective norms,

descriptive norms, ethical consciousness, status consumption, and Muslim religiosity. 455 valid samples

were collected by distributing self-administered questionnaires to undergraduate Muslim students in Greater

Jakarta Area. By utilizing Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), this study uncovers that consumers’

attitude towards counterfeit product was found to be positively and significantly related to purchase

intention of counterfeit fashion product. As for beliefs constructs, the structural model suggest that all belief

variables are significantly influenced the attitudes toward counterfeit fashion products. Furthermore, the

ethical consciousness appears to be the most significant factor that influence attitudes, whereas religiosity

becomes the weakest. The results of the study provide some insights for marketers, manufacturers, policy

makers and religious leaders which may contribute to relieve the global counterfeiting problems.

1 INTRODUCTION

Innovation holds an important aspects the economy.

It plays an important role in encouraging the

formation of creative and unique new products. The

ability to develop and reward innovation is the core

of the producitve and forward-looking global

economy. According to the OECD (2016),

intangible assets such as ideas, copyrights and

brands are part of the innovation, which is shaped as

a tribute to innovators. Unfortunately, a series of

assets and innovations are being threatened by

counterfeiting activity, which became a problem for

global marketers (Penz, Schlegelmilch & Stottinger,

2009). According to the International Anti-

Counterfeiting Organization (2018), counterfeiting is

a form of crime involving the production or

distribution of artificial products, whereby original

products are mimicked and trusted by the

consumers.

Counterfeiting activities and consumer habits in

buying counterfeit products will generate social cost

for the society (Ha & Tam, 2015). As a result,

innovators will be less likely to put effort in new

concepts, which will undoubtedly slow down

innovation and hamper economic growth. OECD

estimated that the value of counterfeit products has

about 5 to 7 percent of all trades made in the global

market and the demand for these products is

estimated to be increased excessively (Quoquab,

Pahlevan, Mohammad, & Thurasamy, 2017;

Hamelin, Nwankwo, and Hadouchi , 2013 in

Hussain, Kofinas, & Win, 2017). As one of the

sizable industries, the fashion industry is negatively

affected by counterfeiting activities. It revealed that

the counterfeit fashion products are the second

largest product which is most consumed by the

Adiprima, D., Indraswari, K. and Kasri, R.

Too Broke for the Hype: Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Fashion Products among Muslim Students.

DOI: 10.5220/0009499213231335

In Proceedings of the 1st Unimed International Conference on Economics Education and Social Science (UNICEES 2018), pages 1323-1335

ISBN: 978-989-758-432-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

1323

public, after the software and CD products

(Zarocostas, 2007 in Nagar, 2016).

A number of studies suggest that counterfeiting

trends are growing more rapidly in developing

countries than in developed countries.

Manufacturers of counterfeit products in emerging

economies are also increasingly interested in

entering into this illegal business as the profit earned

exceeds its risk (Khosrozadeh, 2015; Riquelme,

Abbas, & Rios, 2012). As one of the developing

countries, Indonesia is still struggling with the issue

of counterfeiting activities. According to GTRIC-e

analysis, the concentration of counterfeit goods in

Indonesia is 0.491, on a scale of 0 to 1. It indicates

that almost half of Indonesia's trade is filled with

counterfeit goods and most of them are imported

from other countries (Avery et al., 2008).

As a country with largest Muslim population in

the world, the counterfeiting activities in Indonesia

is certainly contrary to the Islamic norms. Beekun

and Badawi (2015) mentioned that in Islamic norms,

committing acts that violate the rights of others in

material and intellectual matters is prohibited.

Moreover, according to Fatwa No. 1 Year 2005 on

Intellectual Property Rights by the Indonesian

Ulema Council, any behavior that supports

counterfeiting activities (including buying and

selling) is a forbidden act. Similarly, Nahdlatul

Ulama, one of the largest Islamic organizations in

Indonesia, requires Muslim consumers to stay away

from any forms of counterfeiting activities

(Kurniawan, 2017).

Based on the conditions presented above,

research on the consumption of artificial fashion

products in Indonesia becomes relevant. The rise of

counterfeiting activities in the midst of a large

Muslim country becomes an interesting subject for

further investigation. Therefore, this study is

conducted by looking at which factors have

influence on attitudes towards counterfeit fashion

products and intention to purchase counterfeit

fashion products from the point of view of the

Muslim community. This study is focusing on

several factors such as value consciousness, risk,

subjective and descriptive norms, ethical

consciousness, status consumption and muslim

religiosity.

The following sections of this paper will briefly

review the underlying theoretical framework,

hypotheses development and factors contributing to

the attitude and intention to purchase counterfeit

fashion products. Then, we will propose a research

model to explain the relationship between the

factors, attitudes and intention to buy counterfeits

fashion products. Accordingly, we will describe the

research methodology and the empirical result with

some discussion and implications.

2 THEORICAL FRAMEWORK

Staake, Thiesse, and Fleisch (2009) defined

counterfeit products as unauthorized products with

low standard and quality, which are not

manufactured by the original manufacturer. In terms

of fashion, Ha and Lennon (2006) say that

counterfeit fashion products are almost identical

products with original products in terms of display,

packaging, trademarks and labels. Counterfeit

fashion products include apparel, bags, purses,

shoes, watches, perfume, and sunglasses (Kim &

Karpova, 2009; Yoo & Lee, 2009; Simmers,

Schaefer, & Parker, 2015). This study will use this

fashion classification.

Based on the theory of reasoned action by

Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), the purchase behavior of

a consumer is determined by its purchase intention,

which in turn is determined by the attitude towards

the product. They stated that the more positive of

individual belief caused by an object attitude, the

more positive of individual attitude towards the

object, and vice versa. Some studies have found that

one's purchase intention related to artificial products

is strongly explained by attitudes to the product

(Riquelme et al., 2012; Carpenter & Edwards, 2013;

Rahpeima, Vazifedost, Hanzaee, & Saeednia, 2014;

Quoquab et al., 2017 ). Therefore, this study will use

the construction of the intention of purchasing

artificial fashion products that are directly

influenced by individual’s attitudes towards

counterfeit fashion products.

Factors Affecting Attitudes towards Counterfeit

Fashion Products

To generate a research model that is able to explain

and predict, Ajzen and Fishbein's research model

can be added with personality traits and other

external variables that are capable for predicting

related behaviors. Such external stimuli will affect

one's attitudes by modifying the structure of the

person's personal belief (Huang, 2017).

Theoretically, the beliefs also sequentially affect

one's intentions (Quoquab et al., 2017)

The evaluation of counterfeit products made by

consumers is an important predictor of the intention

of purchasing counterfeit products. In addition to

this, the opinions from the surrounding are important

UNICEES 2018 - Unimed International Conference on Economics Education and Social Science

1324

aspects that affect the intention of purchasing

counterfeit products (De Matos, Ituassu, & Rossi,

2007). Quoquab et al. (2017) stated that some

previous studies have also developed various beliefs

related to counterfeit products that can influence

attitudes to counterfeit products, including beliefs

related to social, personal and product aspects.

Eisend and Schuchert-Guller (2006) added that there

are at least four aspects of belief that can affect a

person's attitudes toward the product, namely

personal, product, social and cultural context, and

purchase situation. By taking into consideration

from varios studies that have been described

previously, there are some factors which are

expected to influence one's attitude toward

counterfeit fashion products. The given factors are a

series of beliefs that represent social, personal, and

product aspects.

Value Consciousness

Value consciousness has been defined as a concern

for paying lower prices, subject to some quality

constraint (Ang, Cheng, Lim, & Tambyah, 2001).

Bloch, Bush, and Campbell (1993) revealed that

there are consumers who choose counterfeit

products rather than genuine products if there is a

significant difference on price which causes

consumers to override the quality of a product.

Counterfeit products offer lower quality. But for

some extent, artificial products are considered to

have a function that is not much different from the

original one but with a cheaper price. Furnham and

Valgeirsson (2007) indicated that perceived value

for the counterfeit products will be high for value

conscious consumers. Therefore, we postulate the

following hypothesis:

H1. Value consciousness has a positive influence on

attitudes toward counterfeit fashion products.

Social Risk

Social risk is defined as the probability that a

product will affect the way others think of an

individual who wears the product (Riquelme et al.,

2012). In the context of counterfeit fashion products,

consumers will bear high social risks if there is

discomfort or even discrimination / exclusion they

feel when others realize that consumers are wearing

counterfeit products (Yoo & Lee, 2009; Teik, Seng

& Xin-Yi , 2015). Miyazaki, Rodriguez and

Langenderfer (2009) stated that if the surrounding

environment dissaprove the behavior of buying or

using counterfeit products, then perceived social risk

related counterfeit products for consumers will

increase and reduce consumers’ intention to buy

counterfeit products. Hence, we postulate the

following hypothesis:

H2. Social Risk has a negative influence on attitudes

toward counterfeit fashion products.

Performance Risk

Performance risk can be interpreted as a

probability that the product is malfunctioning so that

the product can not function properly (Riquelme et

al., 2012). Performance risk can arise because

consumers of counterfeit products often get

inappropriate products (Sirfraz, Sabir & Naz, 2007;

Shafique et al., 2015). Performance risk is

considered to affect consumers' purchase intentions

of counterfeit products (Chaykowsky, 2012).

Bamossy and Scammon (1985) argued that

consumers will be motivated to buy counterfeit

products if the performance risk is low (Phau, 2010).

Therefore, we postulate the following hypothesis:

H3. Performance Risk has a negative influence on

attitudes toward counterfeit fashion products.

Subjective Norms

Subjective norm basically refers to a person's

perception of the social pressure their surroundings

to perform or not to perform such behavior (Ajzen,

1991). Consumer intention in purchasing counterfeit

products are also found to depend on normative

pressure or the prevailing social norms (Teik et al.,

2015). If a person thinks that the people around him

agree with the purchase of counterfeit products then

the person will feel the pressure to do the action,

which resulted in the intention of purchasing

artificial products-also increased (Patiro &

Sihombing, 2008; Wijaya & Budiman, 2017).

According to this, we postulate the following

hypothesis:

H4. Subjective Norms has a positive influence on

attitudes toward counterfeit fashion products.

Descriptive Norms

Descriptive norms is a norm that describes the facts

about what actions are done in society (McDonald &

Crandall, 2015). Melnyk, Van Herpen and Van Trijp

(2010) suggested that descriptive norms is a strong

predictor of predicting behavior. When a consumer

wants to make a decision to buy artificial products or

original products, consumers often observe the

social environment and the standards of behavior

within the environment (Tang, Tian, &

Zaichkowsky, 2014). Research conducted by Albers-

Miller (1999) revealed that the presence of friends

who buy an illegal good will make the willingness to

buy counterfeit products of consumers to increase

Too Broke for the Hype: Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Fashion Products among Muslim Students

1325

(Riquelme et al., 2012). Therefore, we postulate the

following hypothesis:

H5. Descriptive Norms has a positive influence on

attitudes toward counterfeit fashion products.

Ethical Consciousness

Schwartz (1992) stated that ethical consciousness

can be defined as an ethical value that is believed by

the individual (Khosrozadeh, 2015). Studies

conducted by Wilcox, Kim, and Sen (2009) and

Quoquab et al. (2017) showed the awareness of the

inherent ethical values in a person has an influence

on one's intention in buying coutnerfeit products.

Both studies showed that a person who has an

ethical awareness that counterfeit products are

morally wrong, will tend not to buy counterfeit

products. Accordingly, we postulate the following

hypothesis:

H6. Ethical Consciousness has a negative influence

on attitudes toward counterfeit fashion products.

Status Consumption

According to Eastman, Fredenberger, Campbell, and

Calvert (1997) in Kim and Karpova (2010), status

consumption is "the motivational process by which

individuals strive to improve their social standing

through conspicuous consumption of consumer

products that confer or symbolise status for both

individuals and surrounding others "(p. 54). Study

conducted by Geiger-Oneto, Gelb, Wakler, and Hess

(2007) indicated that consumers who buy counterfeit

products do so because they want to have products

that can improve their social status without having to

spend money as much as they buy the original

product. Therefore, we postulate the following

hypothesis:

H7. Status consumption has a positive influence on

attitudes toward counterfeit fashion products.

Muslim Religiosity

Saptaluwungan (2015) asserted that the

involvement of the value of religiosity is able to

reduce one's intention in buying counterfeit products

and it is closely related to the belief of those who

consider that the use of counterfeit products is

contrary to religious teachings. It is because the

religious person experiences a fear of God’s

punishment which prevents a person from acting

unethically (Quoquab et al., 2017). The Islamic

community has a worldview influenced by Sharia

teachings. Given that, Muslim consumers will tend

to buy a product which is not violating or contrary to

their beliefs. Hence, the following hypothesis is as

follow:

H8. Muslim Religiosity has a negative influence on

attitudes toward counterfeit fashion products.

Previous Experience

Previous experience in the context of this research

leads to the experience of consumers who have

previously purchased counterfeit products. Ang et al.

(2001) revealed that some consumers who have

bought counterfeit products have different behaviors

when compared to consumers who have never been

buyers of counterfeit products. Tom et al. (1998)

found that the majority of consumers who have

never purchased counterfeit products will not choose

artificial products when offered the opportunity to

purchase the product (Phau, Sequiera, & Dix, 2009).

Previous research has shown that the experience of

buying counterfeit products has a positive

relationship with attitudes toward purchasing

artificial products (Wang et al., 2005; Patiro &

Sihombing, 2008; Nguyen & Tran, 2013; Long &

Vinh, 2017). Consequently, we postulate the

following hypothesis:

H9a. Consumers who have already purchased a

counterfeit fashion products have a more favorable

intention toward counterfeit fashion products.

H9b. Consumers who have already purchased a

counterfeit fashion products have more favorable

attitudes toward counterfeit fashion products than

those who have not bought.

Attitudes

According to Ajzen (2005), attitudes toward

behavior is a positive or negative judgment of a

person involved in performing a particular behavior.

Ajzen (1991) also argued that attitudes are capable

for predicting intention. Matos et al. (2007) stated

that attitudes have a high correlation with one's

intentions therefore it is appropriate to be a predictor

of a behavioral intention (Rahpeima et al., 2014;

Sun, Huang & Lin, 2015). Several studies have

shown that attitudes toward counterfeit goods have a

significant positive relationship to the intention of

buying counterfeit goods (Belleau, Summers, Xu, &

Pinel, 2007; Nguyen & Tran, 2013; Quoquab et al.,

2017). Accordingly, we postulate the following

hypothesis:

H10. Attitudes has a positive influence on intention

to purchase counterfeit fashion products.

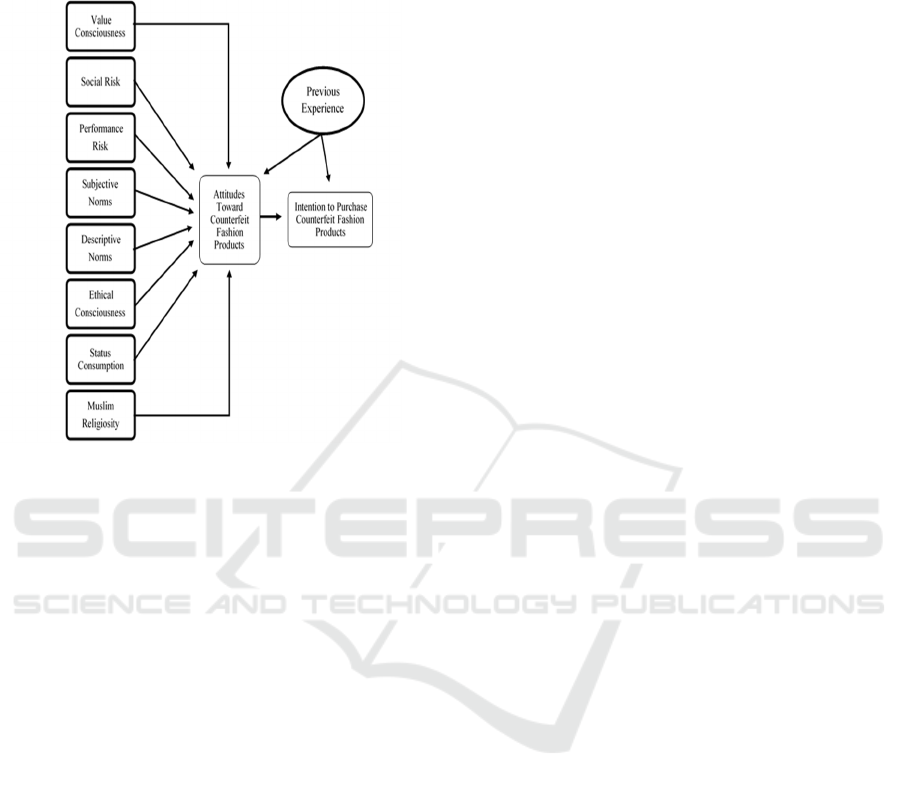

Theoritical Model

Theoretical model proposed in this study is based on

Ajzen and Fishbein's (1975) research model. The

theory that underlies this model is Theory of

Reasoned Action which is also formulated by Ajzen

UNICEES 2018 - Unimed International Conference on Economics Education and Social Science

1326

and Fishbein (1980). The model of this study can be

seen in Figure 1. The model shows that beliefs

influence attitude that in turn influences intention.

Figure 1: Proposed Research Model

3 RESEARCH METHOD

Measurement of the variables

The overall measurement scale used in this study

was taken from some of the earlier relevant studies.

For variable value consciousness, social risk,

performance risk, descriptive norms, ethical

consciousness, social status, attitudes and intention,

measurement scale is taken from research conducted

by Riquelme et al. (2012). Specifically for subjective

norms variable is taken from Chiu and Leng (2015)

and Muslim religiosity variable is taken from Newaz

et al. (2016). The measurement scale used for

variables other than previous experience, is the five-

point Likert where the number 1 shows "strongly

disagree" and 5 shows "strongly agree".

Scope of Study

This study was conducted in Greater Jakarta Area

namely Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang and

Bekasi. The sample used in this study is

undergraduate students who are Muslims. The

undergraduate student group was chosen because

according to Knopper (2007), the student group

represents a group of consumers who often consume

goods that violate copyright. In addition,

Krutkowski (2017) also states that the student group

is a group that often buy counterfeit products

because of the financial limitations. Additionally,

the respondents should be at least 17 years old, since

the age is an adult age for some Mahzab Ulama in

Islam, so it is considered capable of taking a

decision (Buchler & Slatter, 2013).

This study uses purposive sampling technique in

collecting samples because there are screening

questions to filter respondents in accordance with

the research. Questionnaires were distributed online

to undergraduate students who enrolled in

Jabodetabek. This study managed to collect 465

respondents, whereas 455 are considered as valid

respondents.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was done by Structural Equation

Model (SEM) method. According to Kline (2011),

the analysis in SEM is conducted through two stages

of the procedure. First, the overall measurement

model is tested through reliability and validity tests.

Furthermore, the model was again tested with a

series of structural model tests to measure the

linearity of the SEM model constructs studied which

led to hypothesis testing. The data were analyzed

using SPSS Version 25 and LISREL 8.8 software.

4 RESULT & ANALYSIS

Profile of the Respondents

From the 455 valid respondent data, about 301

(66.2%) respondents were female and 154 and the

majority of respondents were in the 20 - 22 years old

age group (79.8%). In terms of area, 41.8% of

respondents are undergraduate students who enrolled

and study in Depok. Furthermore, the majority of

respondents (66%) are undergraduate students who

are completing education at state universities and in

terms of monthly expenditure, 54.9% of the

respondents have an average expenditure around Rp

500,000 - Rp 1,500,000 per month.

Pre-test and Measurement Models

Before conducting further SEM analysis, the entire

construct indicators of the questionnaire tool in this

study has undergone the examination through a

series of pre-tests in the form of realiability and

validity tests. All the indicators in this study are

relatively reliable because it has a value of Construct

Reliability (CR) more than 0.600 (Malhotra, 2010).

The CR value in each variable is quite varied,

ranging from 0.602 for the value consciousness, to

Too Broke for the Hype: Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Fashion Products among Muslim Students

1327

0.947 for the intention variable. In terms of the

validity, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) score of all

indicators are greater than 0.5, and Bartlett's Test of

Sphericity score from overall indicators also less

than 0.05. Therefore, it can be said that the overall

indicators in the questionnaire are valid (Santoso,

2010).

For the SEM measurement model, all of

observed variables or indicators that reflect beliefs

were tested first for the variable validity and

reliability. In this study, all indicators of each

variable have standardized loading factor (

) ≥ 0.50

with t-value more than 1.96. It means that the SEM

measurement model that used in this research were

valid (Wijanto, 2008). Related to the measurement

model reliability, all indicators have a value of

composite reliability (CR) above 0.60, but there is

average variance extracted (AVE) which is slightly

below 0.5. But the low AVE value is still tolerable if

the CR above 0.6, as suggested by O'Rouke and

Hatcher (2013) and Fornell and Larcker (1981).

Thus, it can be said that the measurement model is

relatively reliable. The series of test result can be

seen in more detail in Table 1. The measurement

model was also tested for the goodness of fit. The

GOF test for measurement model resulted in the

following statistics : RMSEA = 0.071, SRMR =

0.065; NNFI = 0.094, CFI = 0.91, PGFI = 0.67,

Normed χ2 = 3.277. With these measurements, it can

be said that the measurement model is in good fit

condition and the analysis can proceed to the next

stage.

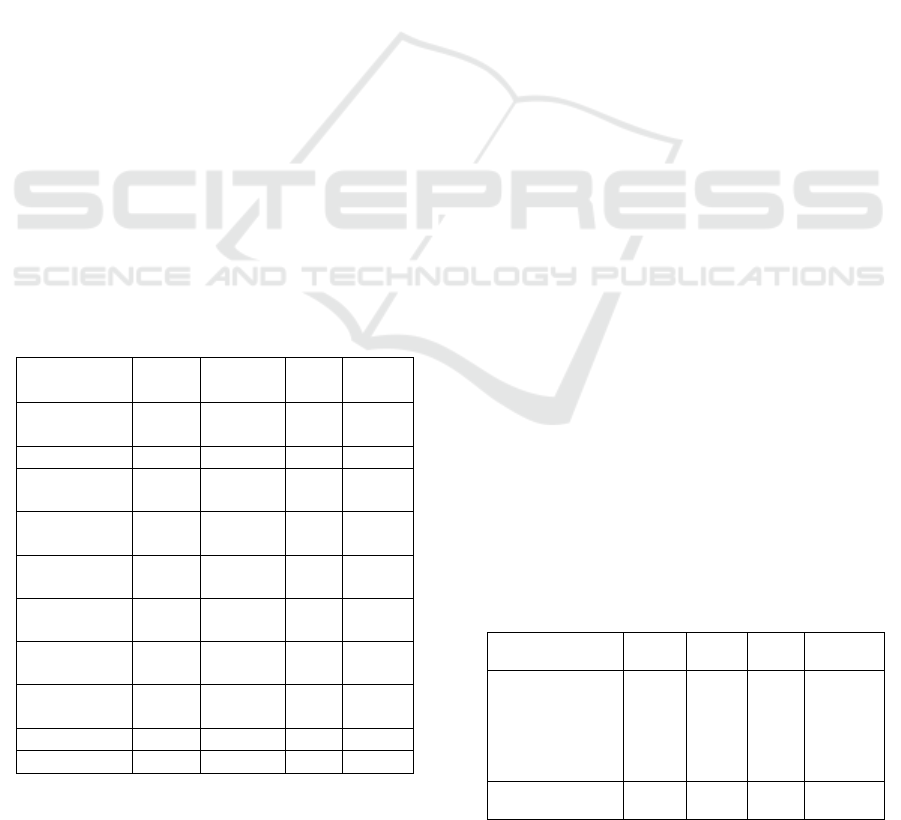

Table 1 : Measurement Model Test Result

Indicators Mean

Mean

SLF (λ)

CR AVE

Value

Consciousness

4.43 0.74 0.79 0.57

Social Risk 4.04 0.73 0.78 0.54

Performance

Risk

3.55 0.67 0.71 0.46

Subjective

Norms

3.04 0.66 0.76 0.44

Descriptive

Norms

3.15 0.78 0.83 0.61

Ethical

Consciousness

3.69 0.75 0.84 0.58

Status

Consumption

3.10 0.79 0.87 0.63

Muslim

Religiosity

4.52 0.68 0.91 0.47

Attitudes 2.41 0.73 0.88 0.54

Intention 2.16 0.82 0.89 0.67

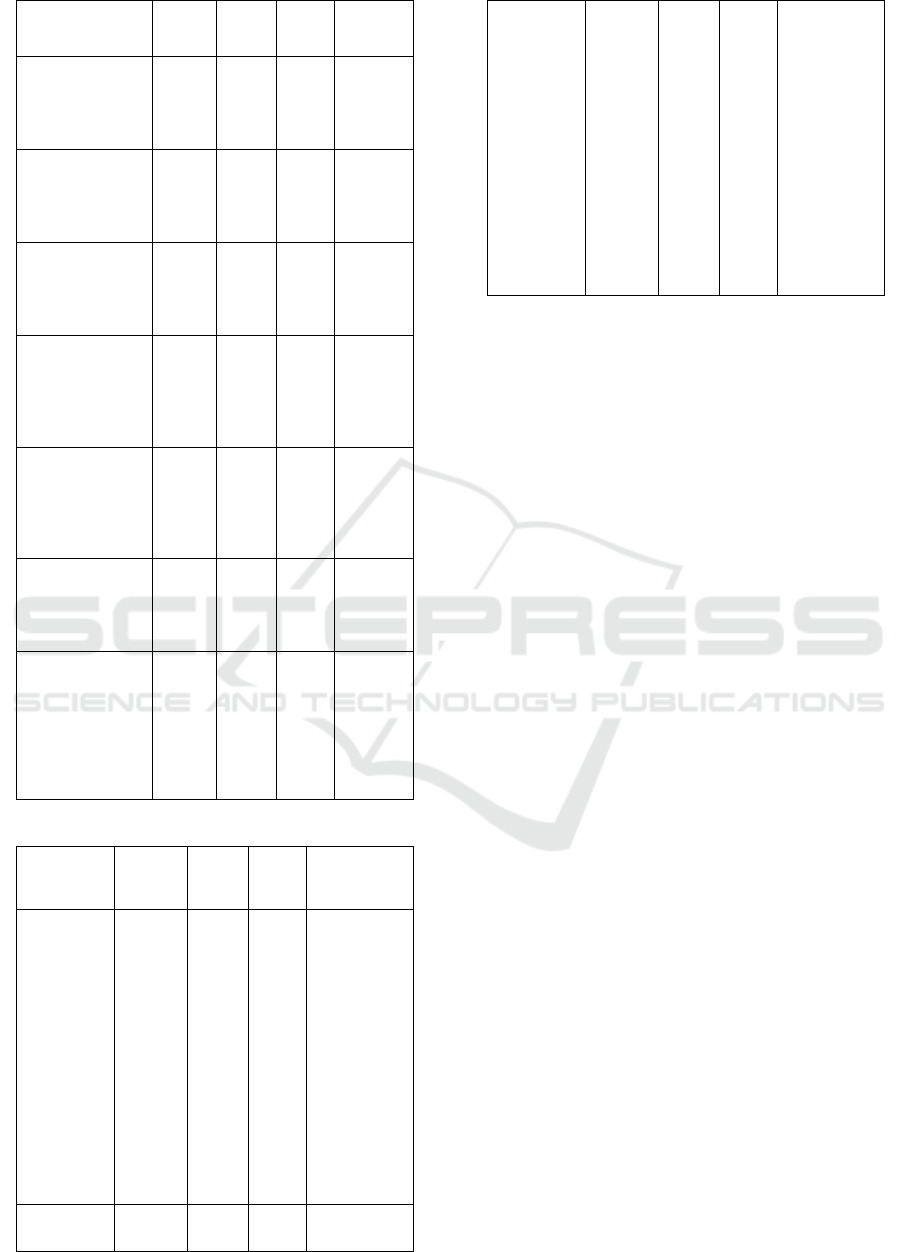

Structural Models and Hypothesis Testing

The Goodness of Fit criteria for the SEM structural

model resulted in the following statistics: RMSEA =

0.077, SRMR = 0.085; NNFI = 0.093, CFI = 0.93,

PGFI = 0.67, Normed χ2 = 3.696. Although SRMR

values are above 0.080, but it can be said that this

structural model is good fit as it refers to the opinion

of Hair et al. (2010, in Latan (2012)) which stated

that a model can be said to be good fit if it at least

meets the four criteria of Goodness of Fit.

In accordance with the basic theory, intention to

purchase counterfeit fashion products are well

described by attitudes toward counterfeit fashion

products with significant percentage (R2 = 74%).

The correlation between intention and attitudes is

very strong with the loading factor score reached

0.86. Then attitudes toward counterfeit fashion

products are reflected significantly by all beliefs,

which are reflected as variables. All variables have a

t-value of ≤ - 1.645 or ≥ 1.645 for a 95% confidence

level. With those results, it is safe to say that all

variables, from the value consciousness to Muslim

religiosity, entirely affect the attitude towards

counterfeit fashion products significantly with

various effect and direction.

Specifically, to analyze the previous experience

variable, a series of ANOVA test were performed

with the aim to compare if those who bought

counterfeit fashion products had a different attitude

and intention towards counterfeit fashion products

(Riquelme et al., 2012). The mean value of the

intention variable for the group who had already

bought counterfeit is 2.81 and the value of those

who had not bought is 1.90. From the ANOVA test

result, the mean difference between those groups are

significantly different. Similarly, the mean

difference between two groups related to the

attitudes variables is also significant where the group

who had already bought counterfeit has a mean

value of 2.95 and the mean value of those who had

not bought is 2.20. The result from testing of

structural model, previous experience and

hypothesis test can be seen in more detail in table 2

and table 3.

Table 2 : Hypotheses Structural Model Test Result

Hypothesis

SLF

(λ)

t-

value

Sig. Decision

H1 : Value

Consciousness +

Attitudes

toward

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

-0.36 -6.31 0.000 Reject

H2 : Social Risk

-- Attitudes

-0.66

-

10.85

0.000 Accept

UNICEES 2018 - Unimed International Conference on Economics Education and Social Science

1328

toward

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

H3 : Performance

Risk --

Attitudes toward

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

-0.52 -8.16 0.000 Accept

H4 : Subjective

Norms +

Attitudes toward

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

-0.65 -9.41 0.000 Reject

H5 : Descriptive

Norms +

Attitudes toward

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

0.53 9.00 0.000 Accept

H6 : Ethical

Consciousness --

Attitudes

toward

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

-0.79

-

13.06

0.000 Accept

H7 : Status

Consumption +

Attitudes

toward

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

-0.15 -2.8 0.002 Reject

H8 : Muslim

Religiosity --

Attitudes toward

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

-0.14 -2.77 0.003 Accept

H10 : Attitudes

toward

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

+ Intention

to Purchase

Counterfeit

Fashion Products

0.86 14.1 0.000 Accept

Table 3 : Hypotheses ANOVA Test Result

Hypot

hesis

F

∆

Mean

Sig. Decision

H9a.

Consumers

who have

already

purchased a

counterfeit

fashion

products,

have a

more

favorable

intention

toward

counterfeit

fashion

products.

93,398 0,75 0.000 Accept

H9b.

Consumers

126,793 0,91 0.000 Accept

who have

already

purchased a

counterfeit

fashion

products,

have more

favorable

attitudes

toward

counterfeit

fashion

products

than those

who have

not bought.

Discussion

Overall, it may well be argued that all of the beliefs

which was investigated in this study have a

significant influence on attitudes toward counterfeit

fashion products. The findings suggest that beliefs

will clearly be influential for consumers in making

their purchase decisions of a counterfeited fashion

products. The relationship between attitude and

intention variables as formulated by Theory of

Reasoned Action is also strongly supported by the

results of the study.

The findings related to the value consciousness

are contrast with previous studies as found in the

Riquelme et al. (2012) and Bhatia (2018). Besides,

there are other studies which also did not found any

positive relationship between the value

consciousness with attitudes toward counterfeit

products, such as Phau, Teah, and Lee (2009) and

Dewanthi (2015). The results of this study suggest

that the more person is aware of the value, the more

negative his attitude toward counterfeit fashion

products. One possible explanation of the existence

of such a negative relationship can be seen from the

emergence of alternative products from counterfeit

fashion products which is the preloved fashion

products. In terms of price range, some preloved

fashion products are in the same level as the

counterfeit fashion products. Although it is preloved,

many of them are original products with guaranteed

authenticity, even some of the products were also in

very good or mint ‘like new’ condition. For someone

who values conscious, the condition will probably

change his view in assessing the ratio of the benefits

and prices offered by a fashion product in the

markets.

The possibility is strengthened by some studies

that conducted by Dwiyantoro and Hariyanto (2014)

which discovered that used clothing products are

increasingly popular among students for the reasons

of price factors. The development of buying and

Too Broke for the Hype: Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Fashion Products among Muslim Students

1329

selling activities of preloved products can clearly be

seen from the emergence of online market platforms

in Indonesia that provide facilities to sell and buy

preloved fashion products, such as Carousell,

Tinkerlust, Shopee and Prelo (Sudradjat, 2018). In

addition to the online-based market platform,

Mubarak and Sanawiri (2018) specified that social

media platforms are also used by sellers and buyers

to exchange and share information about used

clothing products. An online survey also shows that

about 8 out of 10 Indonesians are willing to buy

used goods and preloved branded fashion products

become one of the most popular preloved goods on

all categories (Anggoro, 2017).

Morover, findings on social risk provide results

that are consistent with previous studies such as

research conducted by Vida (2007), Tang et al.

(2014), and Krutkowski (2017). Social risk will have

strong effects on society with collective culture

(Krutkowski, 2017). Society which has collective

culture will consider the perception of other people's

on viewing himself are really important. Some

researchers have pointed out that Indonesian society

is a society that has collective culture (Hofstede &

Hofstede, 2005 in Mangundjaya, 2013; Sumantri &

Suharnomo, 2011). Therefore, it is acceptable if

social risk has a significant result in this study.

From the performance risk, the results of this

study are also in line with some previous research

such as research conducted by Bian and Moutinho

(2011) and Riquelme et al. (2012). The average

score of respondents' answers related to perceived

performance risk to the counterfeit fashion products

turned out to be not really high (3.55). It indicates

that the majority of respondents do not strongly

perceive the counterfeit fashion products has poor

quality and is not comparable with the original

product. These conditions may occur because the

purpose of purchasing counterfeit products such as

fashion products is generally to feel the sensation of

using original products at lower prices rather than

find some good quality products (Phau, Sequiera &

Dix, 2009). Furthermore, the inherent risks of

counterfeit fashion products cannot be separated

from their physical quality because the use of

fashion products are noticed physically by others

(Chaykowsky, 2012). Thus, it may be argued that

although the majority of respondents in this study do

not view counterfeit fashion products as low quality

products, a possible negative relationship may arise

because respondents' performance risk perceptions

often associated with physical product quality that

may create negative stigma from others towards

themselves.

Related to subjective norms, the findings of this

study are contrast with some previous research

results, such as research from Kim and Karpova

(2010) and Riquelme et al. (2012). However, there

are also another studies that do not find any negative

relationship between subjective norms and attitudes

toward counterfeit products, such as research

conducted by De Matos et al. (2007) and Lu (2013).

Theoretically, the negative relationships of the

subjective norms and attitudes indicate that most

respondents in this study did not have or low score

of motivation to comply (Goulet, Lampron, Marcil,

& Ross, 2003). In addition, the findings in this study

are most likely related to the characteristics of

respondents that used in this study which all of the

respondents were students who were mostly 20-22

years old. Goulet et al. (2003) revealed that one of

the typical traits of young generation is to have

behaviors and thoughts that are opposed to their

surroundings such as parents, family and relatives. It

is done solely to affirm that they are free, self-

sufficient and impartial with the values that believed

by their closest person. Gellner (1968) also stated

that a young person tends to be more 'rebellious'

when compared to an elderly person. Thus, it is

reasonable that the subjective norm has a negative

relationship with attitude. Whereas pertaining to

descriptive norms, the results are in line with the

research of Riquelme et al. (2012). In terms of

descriptive norm, a particular norm that ‘promoting

an action’ would have a greater impact on a person,

than the norm that ‘preventing’ an action (Melynk et

al., 2013 in McDonald & Crandall, 2015).

It was found in this study that ethical

consciousness were in accordance with some

previous studies such as research written by

Riquelme et al. (2012), Wilcox et al. (2009) and

Quoquab et al. (2017). Tang et al. (2014) explained

that the ethical consciousness is closely related to

the judgment of others to an individuals, whereas the

ethically conscious person would be praised, while

the person that does not put attention into ethics will

often got bad assumptions and criticism. The

element of idealism in ethical thinking may also

affect the ethical consciousness of a person related

to his attitudes toward fashion products. An idealist

has a really high desire to be the right person and in

line with moral conduct (Sharif, Asanah &

Alamanda, 2016).

From the status consumption aspect, the study

showing a results that are contrary to some previous

studies, such as research from Prakash and Pathak

(2017), Haseeb and Mukhtar (2016), and a Ha and

Tam (2015). However, on the other hand there are

UNICEES 2018 - Unimed International Conference on Economics Education and Social Science

1330

some previous studies that have similar findings

with this study, such as research from Budiman

(2012), Basu, Basu, and Lee. (2015) and Riquelme

et al. (2012). The findings showed that when

respondents are a type of person who is motivated to

buy a fashion product that can improve their social

status, respondents will have a negative attitudes

toward counterfeit fashion products because in some

circumstances, using counterfeit fashion products

may actually threaten the social status of the person.

In addition Rod et al. (2015) explained that the goal

of obtaining social status through the use of

counterfeit fashion products is unlikely to be

achieved if the surrounding environments are aware

with the act of using or buying counterfeit.

Moreover, Triandewi and Tjiptono (2013), stated

that the social status of a product is often depicted

from its authenticity.

The results of the Muslim religiosity in this

research are fairly in accordance with the results of

research conducted by some previous research, such

as research conducted by Quoquab et al. (2017) and

Vida (2007). The results of this study indicate that a

person will tend to have a negative attitude toward

fashion products imitation, if they are more obedient

and stick to the Islamic values. The high average

score from Muslim religiosity responses in this study

(4.52) indicates that the majority of respondents

acknowledge themselves as a religious person.

However, it turns out that Muslim religiosity has the

smallest effect towards one's attitude on counterfeit

fashion products. This condition suggest that the

teachings regarding the prohibition of counterfeiting

activities have not been implemented properly. This

is in line with the research from Zaman, Jalees, Jiang

and Kazmi (2017) which revealed that Muslims

sometimes do not understand that buying artificial

products is un-Islamic. Similarly, Budiman (2012)

also uncovered that most people in Indonesia do not

see the activities of counterfeiting as a sinful activity

which may inflict a sin as stealing activity (because

counterfeit means steal the ideas of others), but

rather view that the activities of counterfeiting is just

an activity that is breaking the legal or law.

Although the findings on religiosity in the

context of this study do not clearly reflect the actual

teachings of Islam that should be implemented in the

society, religiosity is able to influence one's attitude

toward fashion products by another way. Some

previous studies have found that religiosity is closely

related to one's ethics. Quoquab, Pahlevan, and

Hussin (2016) suggested that a person with high

religiosity will have a more ethical attitude in

response to a counterfeit product. In addition to

ethics, religiosity is also considered as a factor that

reinforces the perception of social consequences that

a person will accept (Riquelme et al., 2012;

Khosrozadeh, 2015). Therefore, it is possible in the

context of this study that religiosity plays a

significant role by influencing the ethics and

perceptions of one's shyness. Lastly, from the

previous experience variable, a person who had a

previous purchases of counterfeit products has a

different outlook with someone who did not have an

experience to buy counterfeit products because

someone with such experience was more daring to

take risks and did not think much about ethical

elements (Dhaliwal, 2016). The result is consistent

with former studies by Riquelme et al. (2012),

Zeashan et al. (2015), and Nguyen and Tran (2013)

5 CONCLUSIONS

World market conditions are increasingly integrated

along with the globalization and technological

progress, resulting in rampant production and

distribution of counterfeiting products (Kim &

Johnson, 2014). All elements including

governments, brand owners and producers must

adapt and innovate to continue exploring new ways

to 'annoy counterfeiters' and make it more difficult

and costly for them to succeed (McCue & Aikman-

Scalese, 2017). This study is expected to give

additional contribution in explaining this phenomena

from the consumers’ perspective. This study

provides a new perspective from Muslim religiosity

as well as from young consumer side in Greater

Jakarta areas. We apply Ajzen's theory of reasoned

action that predicts that beliefs affect attitudes and in

turn influence the intention to behave in a certain

way. Based on the result of this study, it can be

concluded that the research models based on Theory

of Reasoned Action by Ajzen and Fishbein (1975) is

quite comprehensive in explaining consumer

behavior related to counterfeit fashion products.

Interestingly, the finding of this study indicates

that ethical consciousness is the most significant

factor affecting attitudes toward fashion products,

but in a negative direction. It can be an indication

that young consumers are idealistic consumers who

begin to consider ethics in consumption activities,

although not all respondents behave that way.

Moreover, the social risk factor becomes the second

most significant factor influencing attitude toward

counterfeit fashion product. This finding is

supported by the findings of performance risk

variable which shows that the majority of

Too Broke for the Hype: Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Fashion Products among Muslim Students

1331

respondents in this study do not view counterfeit

fashion products as poor products, but they associate

its quality with below-average performance. It will

certainly reinforce the negative perception of others

against him, if he wears a product with inferior

quality.

In terms of religiosity, this study discovered that

Islamic values are significant factors although their

effects are relatively weak. This condition exhibits

that Islamic values can be a factor that determines

the consumption of an individual. However, the

teachings and rules that specifically limit the

purchase and use of counterfeit products may not be

properly applied and implanted by a Muslim.

Therefore, it is the task of the authorities to

disseminate the syiar that discusses the religious

views of Islam against artificial products.

Considering the limitations of the research, some

cautions should be considered in the generalization

of its results. Due to repsondents’ characteristics,

this study may only useful for young adult or student

consumers context. To enhance a better

understanding under this topic, further studies may

compare within specific fashion products and

compare each results (e.g. wallet vs bags, sunglasses

vs jeans, etc.). It is also strongly suggested to test the

model in such different society that have a different

culture from Indonesia. It also recommended for the

future studies to investigate the religiosity effect on

some other major religions or beliefs.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 50, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-

5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 50, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-

5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1975), Belief, Attitude,

Intention and Behavior: An Intoduction to Theory and

Research, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding atti- tudes

and predicting social behavior. Englewood, Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

Alhafiz Kurniawan. (2017). Hukum Penggunaan Barang

Bajakan atau KW (1) | NU Online. Retrieved March

28, 2018, from

http://www.nu.or.id/post/read/74595/hukum-

penggunaan-barang-bajakan-atau-kw-1

Ang, S. H., Cheng, P. S., Lim, E. A. C., & Tambyah, S. K.

(2001). Spot the difference: Consumer responses

towards counterfeits. Journal of Consumer Marketing,

18(3), 219–233.

Anggoro, A. (2017). Transaksi Barang Preloved Makin

Digemari | SWA.co.id. Retrieved June 02, 2018, from

https://swa.co.id/swa/trends/transaksi-barang-

preloved-makin-digemari

Avery, P., Cerri, F., Haie-Fayle, L., Olsen, K. B.,

Scorpecci, D., & Stryszowski., P. (2008). The

Economic Impact of Counterfeiting and Privacy.

OECD Publishing.

Basu, M. M., Basu, S., & Lee, J. K. (2015). Factors

Influencing Consumer’s Intention to Buy Counterfeit

Products. Global Journal of Management and

Business Research: (B) Economics and Commerce,

15(6).

Beekun, R. and Badawi, J. (2005). Balancing ethical

responsibility among multiple organizational

stakeholders: the Islamic perspective. Journal

ofBusiness Ethics, 60, 131 - 145

Belleau, B. D., Summers, T. A., Xu, Y., & Pinel, R.

(2007). Theory of reasoned action: Purchase intention

of young consumers. Clothing and Textiles Research

Journal, 25(3), 244–257.

Bhatia, V. (2018). Examining consumers’ attitude towards

purchase of counterfeit fashion products. Journal of

Indian Business Research, 10(2), 193–207.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-10-2017-0177

Bian, X., & Moutinho, L. (2011). The role of brand image,

product involvement, and knowledge in explaining

consumer purchase behaviour of counterfeits.

European Journal of Marketing, 45(1/2), 191–216.

Bloch, P. H., Bush, R. F., & Campbell, L. (1993).

Consumer ‘Accomplices’ in Product Counterfeiting: A

Demand-Side Investigation. Journal of Consumer

Marketing, 27-36.

Büchler, A., & Schlatter, C. (2013). Marriage Age in

Islamic and Contemporary Muslim Family Laws A

Comparative Survey. Electronical Journal of Islamic

and Middle Eastern Law, 1.

Budiman, S. (2012). Analysis of Consumer Attitudes to

Purchase Intentions of Counterfeiting Bag Product in

Indonesia. International Journal of Management,

Economics and Social Sciences, 1(1), 1–12.

Carpenter, J. M., & Edwards, K. E. (2013). U.S.

Consumer Attitudes toward Counterfeit Fashion

Products. Journal of Textiles and Apparel, 8(1), 1–16.

Chaykowsky, K. (2012). Examining the effects of apparel

attributes on perceived copyright infringement and the

relationship between perceived risks and purchase

intention of knockoff fashion. ProQuest Dissertations

and Theses. Retrieved from

http://search.proquest.com/docview/1466003189?acco

untid=51189

Chiu, W., & Leng, H. K. (2015). Is That a Nike ? The

Purchase of Counterfeit Sporting Goods through the

Lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sport

Management International Journal, 11(1), 80–94.

De Matos, A., Ituassu, C. T., & Rossi, C. A. V. (2007).

Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits: a review and

UNICEES 2018 - Unimed International Conference on Economics Education and Social Science

1332

extension. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(1), 36–

47.

Dewanthi, D. S. (2015). Faktor Sosial Dan Personal Yang

Mempengaruhi Konsumen Membeli Barang Fashion

Tiruan (Counterfeited Fashion Goods). Journal of

Business Strategy and Execution, 8(1), 25–43.

Dhaliwal, A. (2016). Determinants Affecting Consumer

Behaviour With Regard To Counterfeit Products.

International Journal of Scientific Research and

Management (IJSRM), 4(6), 4243–4249.

Dwiyantoro, A., & Harianto, S. (2014). Fenomenologi

Gaya Hidup Mahasiswa UNESA Pengguna Pakaian

Bekas. Jurnal Paradigma, 2(3), 2014.

Eisend, M., & Schuchert-güler, P. (2006). Explaining

Counterfeit Purchases : A Review and Preview.

Academy of Marketing Science Review, 10(12), 214–

229.

Elgaaied-Gambier, L., Monnot, E., & Reniou, F. (2018).

Using descriptive norm appeals effectively to promote

green behavior. Journal of Business Research, 82,

179–191.

Furnham, A., & Valgeirsson, H. (2007). The effect of life

values and materialism on buying counterfeit products.

Journal of Socio-Economics, 36(5), 677–685.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural

Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and

Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research,

18(1), 39.

Geiger-Oneto, S., Gelb, B.D., Walker, D., & Hess, J.D.

(2012, October). “Buying status” by choosing or

rejecting luxury brands and their counterfeits. Journal

of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40,357–372.

Gellner, E. (1968). The New Idealism - Cause and

Meaning in the Social Sciences. Studies in Logic and

the Foundations of Mathematics (Vol. 49). North-

Holland Publishing Company.

Goulet, C., Lampron, A., Marcil, I., & Ross, L. (2003).

Attitudes and subjective norms of male and female

adolescents toward breastfeeding. Journal of Human

Lactation, 19(4), 402–410.

Ha, N. M., & Tam, H. L. (2015). Attitudes and Purchase

Intention Towards Counterfeit

Ha, S., & Lennon, S. J. (2006). Purchase intent for fashion

counterfeit products: Ethical ideologies, ethical judg-

ments, and perceived risks. Clothing and Textile

Research Journal, 24(4), 297-315.

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L and Black, W.C.

(2009). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th Edition. USA,

Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Haseeb, A., & Mukhtar, A. (2016). Antecedents of

Consumer ’ s Purchase Intention of Counterfeit

Luxury Product. Journal of Marketing and Consumer

Research, 28, 15–25.

Huang, H. (2017). The Theory of Reasoned Action :

Shanzhaiji or Counterfeit. SciencePG : Chinese

Language, Literature & Culture, 2(2), 10–14.

https://doi.org/10.11648/j.cllc.20170202.11

Hussain, A., Kofinas, A., & Win, S. (2017). Intention to

Purchase Counterfeit Luxury Products: A Comparative

Study Between Pakistani and the UK Consumers.

Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 29(5),

331–346.

IACC. (2018). What is Counterfeiting | IACC. Retrieved

June 22, 2018, from

https://www.iacc.org/resources/about/what-is-

counterfeiting

Khosrozadeh, S. (2015). Investigating fake product’s

purchase behavior. Applied Mathematics in

Engineering, Management and Technology, 3(4), 424–

431.

Kim, H., & Karpova, E. (2010). Consumer attitudes

toward fashion counterfeits: Application of the theory

of planned behavior. Clothing and Textiles Research

Journal, 28(2), 79–94.

Kim, J. E., & Johnson, K. K. P. (2014). Shame or pride?:

The moderating role of self-construal on moral

judgments concerning fashion counterfeits. European

Journal of Marketing, 48(7–8), 1431–1450.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural

equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling

(Vol. 156).

Knopper, S. (2007). “RIAA campaign rejected by

colleges”, Rolling Stone, April 19, p. 12.

Latan, Hengky. (2012). Structural Equation Modeling

Konsep dan Aplikasi Menggunakan Program LISREL

8.80. Bandung: Alfabeta.

Lu, M. (2013). An investigation of consumer motives to

purchase counterfeit luxury-branded products.

University of Wollongong.

Long, H. C., & Vinh, N. N. (2017). Factors Influencing

Consumers’ Attitudes Towards Counterfeit Luxury

Fashion Brands : Evidence From Vietnam. Global

Journal of Management and Marketing, 1(2), 63–75.

Majelis Ulama Indonesia. (2005). Fatwa Majelis Ulama

Indonesia Nomor: 1/Munas Vii/Mui/5/2005 Tentang

Perlindungan Hak Kekayaan Intelektual (HKI).

Retrieved from http://www.dgip.go.id/images/ki-

images/pdf-files/FatwaMUI.pdf

Malhotra, N. K., Birks, D. F., & Wills, P. (2010).

Marketing Research : An Applied Approach.

Marketing Research (3rd Edition). Harlow: Pearson

Education Limited.

Maman, A. F. (2008). Non-deceptive Counterfeiting of

Luxury Goods: A Postmodern Approach to a

Postmodern (Mis) behaviour.

Mangundjaya, W. L. (2013). Is There Cultural Change In

The National Cultures Of Indonesia? Steering the

Cultural Dynamics, (2010), 59–68.

McCue, M. J., & Aikman-Scalese, A. (2017). Alternative

strategies for fighting counterfeits online - World

Trademark Review. Retrieved June 28, 2018, from

http://www.worldtrademarkreview.com/Intelligence/O

nline-Brand-Enforcement/2017/Chapters/Alternative-

strategies-for-fighting-counterfeits-online

Mcdonald, R. I., & Crandall, C. S. (2015). Social norms

and social influence. Current Opinion in Behavioral

Sciences, 3, 147–151.

Melnyk, V., van Herpen, E., & van Trijp, H. C. M.

(2010). The influence of social norms in consumer

decision making: A meta-analysis. In M. C. Campbell,

Too Broke for the Hype: Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Fashion Products among Muslim Students

1333

J. Inman, & R. Pieters (Vol. Eds.), Advances in

consumer research. 37, 463–464. 464). Duluth, MN:

Association for Consumer Research.

Miyazaki, A., Rodriguez, A.A. and Langenderfer, J.

(2009), “Price, scarcity, and consumer willingness to

purchase pirated media products”, Journal of Public

Policy & Marketing, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 71-84.

Mubarak, S. A., & Sanawiri, B. (2018). Pengaruh Fashion

Lifestyle Terhadap Purchase Intention ( Studi Pada

Konsumen Pakaian Second Hand @ Tangankedua ).

Jurnal Administrasi Dan Bisnis, 55(3).

Nagar, K. (2016). Mediating effect of self-control between

life satisfaction and counterfeit consumption among

female consumers. Journal of Global Fashion

Marketing, 7(4), 278–290.

Newaz, F. T., Fam, K. S., & Sharma, R. R. (2016).

Muslim religiosity and purchase intention of different

categories of Islamic financial products. Journal of

Financial Services Marketing, 21(2), 141–152.

Nguyen, P. V., & Tran, T. T. B. (2013). Modeling of

Determinants Influence in Consumer Behavior

towards Counterfeit Fashion Products. Business

Management Dynamics, 2(12), 12–23.

O’Rouke, N., & Hatcher, L. (2013). A Step-by-Step

Approach to Using SAS® for Factor Analysis and

Structural Equation Modeling, Second Edition. SAS

Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA

Patiro, S. P. S., & Sihombing, S. O. (2008). Predicting

Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Products : Extending

the Theory of Planned Behavior. International

Research Journal of Business Studies, 7(2), 109–120.

Penz, E., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Stottinger, B. (2009).

Voluntary purchase of counterfeit products: Empirical

evidence from four countries. Journal of International

Consumer Marketing, 21(1), 67–84.

Phau, I. (2010). Predictors and Purchase Intentions of

Counterfeits of Luxury Branded Products. Curtin

University of Technology.

Phau, I., Sequeira, M., & Dix, S. (2009). Consumers’

willingness to knowingly purchase counterfeit

products. Direct Marketing: An International Journal,

3(4), 262–281.

Phau, I., Sequeira, M., & Dix, S. (2009). To buy or not to

buy a “counterfeit” Ralph Lauren polo shirt. Asia-

Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 1(1), 68–

80.

Phau, I., Teah, M., & Lee, A. (2009). Targeting buyers of

counterfeits of luxury brands: A study on attitudes of

Singaporean consumers. Journal of Targeting,

Measurement and Analysis for Marketing

, 17(1), 3–

15.

Prakash, & Pathak. (2017). Determinants of Counterfeit

Purchase: An Investigation on Young Rural

Consumers of India. Journal of Scientific & Industrial

Research, 76(April), 208–211.

Quoquab, F., Pahlevan, S., & Hussin, N. (2016).

Counterfeit product purchase: What counts—

materialism or religiosity? Advanced Science Letters,

22(5–6), 1303–1306.

Quoquab, F., Pahlevan, S., Mohammad, J., & Thurasamy,

R. (2017). Factors affecting consumers’ intention to

purchase counterfeit product. Asia Pacific Journal of

Marketing and Logistics, 29(4), 837–853.

Rahpeima, A., Vazifedost, H., Hanzaee, K. H., &

Saeednia, H. (2014). Attitudes toward counterfeit

products and counterfeit purchase intention in non-

deceptive counterfeiting : role of conspicuous

consumption , integrity and personal gratification.

WALIA Journal, 30(S3), 59–66.

Riquelme, H. E., Mahdi Sayed Abbas, E., & Rios, R. E.

(2012). Intention to purchase fake products in an

Islamic country. Education, Business and Society:

Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 5(1), 6–22.

Rod, A., Rais, J., Schwarz, J., & Čermáková, K. (2015).

Economics of Luxury: Counting Probability of Buying

Counterfeits of Luxury Goods. Procedia Economics

and Finance, 30(15), 720–729.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01321-0

Saptalawungan, S. (2015). Hesitation To Buy Counterfeit

Products : an Indonesian Perspective. In Proceedings

of International Conference on Management Finance

Economics (pp. 118–124).

Santoso, S. (2010). Statistik Multivariat : Konsep dan

Aplikasi dengan SPSS. Jakarta : PT Elex Media

Komputindo.

Shafique, M. N., Ahmad, N., Abbass, S., & Khurshid, M.

M. (2015). Consumer Willingness toward Counterfeit

Products in Pakistan: An Exploratory Study. Journal

of Marketing and Consumer Research Journal, 9, 29–

35.

Sharif, O. O., Asanah, A. F., & Alamanda, D. T. (2016).

Consumer Complicity With Counterfeit Products.

АКТУАЛЬНІ ПРОБЛЕМИ ЕКОНОМІКИ, 1(175),

247–252.

Simmers, C. S., Schaefer, A. D., & Parker, R. S. (2015).

Counterfeit luxury goods purchase motivation : A

cultural comparison. Journal of International Business

and Cultural Studies, 9, 1–15.

Sirfraz, M., Sabir, H. M., & Naz, H. N. (2014). Impact of

Perceived Risk on Customers ’ Buying Intentions for

Counterfeit Tablet PCs in Central. International

Journal of Management & Organizational Studies,

3(3), 45–50.

Staake, T., Thiesse, F., Fleisch, E. (2009). The emergence

of counterfeit trade: a literature review. European

Journal of Marketing 43(3/4), 320-349.

Sumantri, S., & Suharnomo. (2011). Kajian proposisi

hubungan antara dimensi budaya nasional dengan

motivasi dalam suatu organisasi usaha. Pustaka

Universitas Padjajaran.

Sun, P., Huang, H., & Lin, M. (2015). Chinese Buying

Luxury Counterfeits Behavior : The Role Of Social

Influence And Personal Gratification. International

Journal of Management and Applied Science, 1(9),

26–30.

Tang, F., Tian, V.-I., & Zaichkowsky, J. (2014).

Understanding counterfeit consumption. Asia Pacific

Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 26(1), 4–20. F

UNICEES 2018 - Unimed International Conference on Economics Education and Social Science

1334

Teik, D., Seng, T., & Xin-Yi, A. (2015). To Buy or To

Lie: Determinants of Purchase Intention of Counterfeit

Fashion in Malaysia. International Conference on

Marketing and Business Development Journal, 1(1),

49–56.

Triandewi, E., & Tjiptono, F. (2013). Consumer Intention

to Buy Original Brands versus Counterfeits.

International Journal of Marketing Studies, 5(2), 23–

32. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v5n2p23

Tsana Garini Sudradjat. (2018). Ikutan Tren Jual Barang

Preloved, Why Not? Retrieved May 28, 2018, from

http://www.gogirl.id/news/life/ikutan-tren-jual-barang-

preloved-why-not-S13472.html

Vida, I. (2007). Determinants of Consumer Willingness to

Purchase Non-Deceptive Counterfeit Products.

Managing Global Transitions, 5(3), 253–270.

Wang, F., Zhang, H., Zang, H., & Ouyang, M. (2005).

Purchasing pirated software: an initial examination of

Chinese consumers. Journal of Consumer Marketing,

22(6), 340–351.

https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760510623939

Wee, C.-H., Tan, S.-J., & Cheok, K.-H. (1995). Non-price

determinants of intention to purchase. International

Marketing Review, 12(6), 19–46.

Wijanto, Setyo Hari. (2008). Structural Equation

Modeling dengan LISREL 8.8. Yogyakarta: Graha

Ilmu.

Wijaya, T., & Budiman, S. (2017). Purchase Intention of

Counterfeit Products : The Role of Subjective Norm

Purchase Intention of Counterfeit Products : The Role

of Subjective Norm. International Journal of

Marketing Studies, 6(2), 145–152.

Wilcox, K., Kim, H. M., & Sen, S. (2009). Why Do

Consumers Buy Counterfeit Luxury Brands? Journal

of Marketing Research, 46(2), 247–259.

Yoo, B., & Lee, S. H. (2009). Buy Genuine Luxury

Fashion Products Or Counterfeits?. Advances in

Consumer Research, 36, 280-286.

Zaman, S. I., Jalees, T., Jiang, Y., & Kazmi. (2017).

Testing and incorporating additional determinants of

ethics in counterfeiting luxury research according to

the theory of planned behavior *. PSIHOLOGIJA, 1–

34.

Zeashan, M. (2015). Consumer Attitude towards

Counterfeit Products : With Reference to Pakistani

Consumers. Journal of Marketing and Consumer

Research, 12, 1–14.

Too Broke for the Hype: Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Fashion Products among Muslim Students

1335