Development of the Information Economy in India

and the Role of Diaspora

The Missing Intercourse

Reza Akbar Felayati

1

, Joko Susanto

2

1

Department of International Relations, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

2

Department of International Relations, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: India, information economics, diaspora, human capital

Abstract: India experienced a unique development phenomenon in the late 1980s to 1990s when the IT sector, in the

form of production, software exports, and services related to computers and IT, became dominant in the

Indian economy. As in developing countries in general, India is faced with the problem of inadequate

human capital when it comes to achieving modern economic levels, and the industrial and manufacturing

sectors hampered by regulative government policies. Looking at the situation as it stands; India has reached

the stage of what is called the information economy, which is the typical economic style of developed

countries. Using the diaspora role approach as a state development actor, the authors have a hypothesis that

the success of India in addressing the problems of human capital needs relates to their success in utilizing

the diaspora that acts as a technological and knowledge transfer initiator, an additional number of human

capital, and as transnational bridges between multinational and state enterprises. In other words, the

diaspora is the link that allows India to jump to the stage of information economy.

1 INTRODUCTION

India's growing development in IT is a unique

phenomenon, because as a developing country, India

has a dominant information economy and this can be

seen from several facts about India. Firstly, there are

various regions of India that have developed into IT

incubation centers that are full of information-based

economies. One of them is Bengaluru, known as the

Silicon Valley of India, which accounts for 38% of

India's IT exports, making it the IT Capital of India

(Arora et al., 2013). India’s position as one of the

global IT centers and as a software export center is

done through Bengaluru. Some of the leading IT

companies such as Intel, Texas Instruments, Bosch,

Yahoo, SAP Labs, and Continental, have now

opened their research centers in Bengaluru. With

astonishing Indian achievements, India has shown

itself to the world as a country that will lead Asia as

the spearhead of the global economy and in

technological developments.

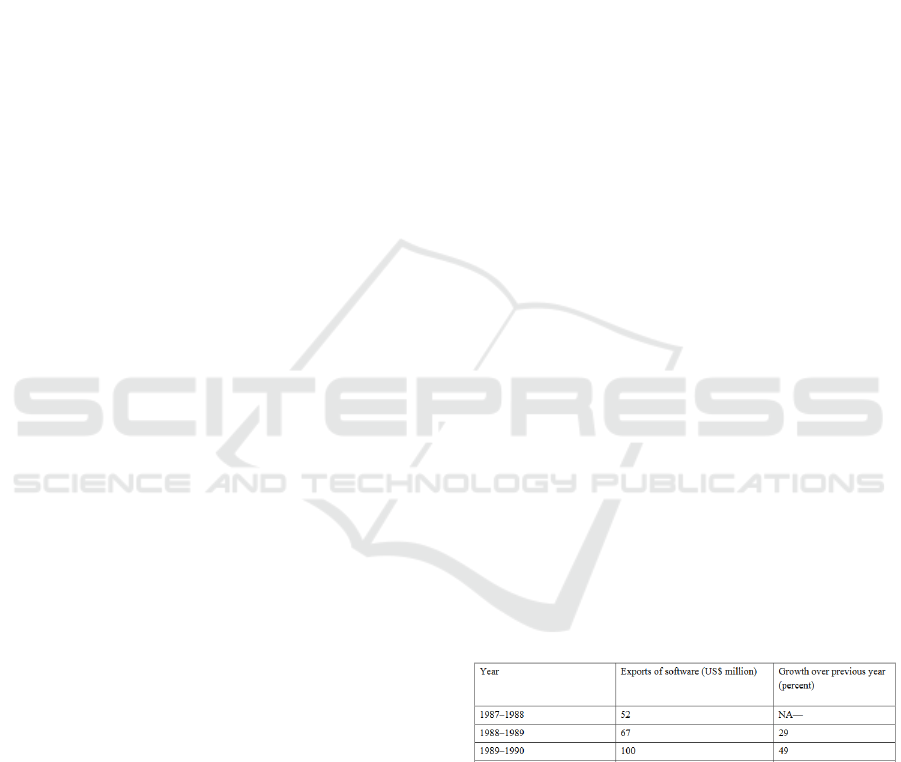

This can be seen from one sub-sector that has

shown a significant improvement; the software

sector, especially in relation to exports. As Table 1

shows, from 1987-1988 to 1989-1990, India's

software exports rose from $52 million to $100

million, nearly doubling over four years. In terms of

this growth percentage, it is noted that software

exports in India reached 78 percent in the same

period.

Table 1: Export of Indian software from 1987 to 1990

Eichengreen and Gupta (2010) also said that with

respect to the service sector, revenues derived from

activities based on IT and telecommunications are

dominant. This is evident from the composition of

the services sector in India dominated by software,

business services and communications in 1990.

Software exports that occupy 64 percent of the total

revenue from the service sector. This is followed by

business services at 27 percent, and then finances (5

Felayati, R. and Susanto, J.

Development of the Information Economy in India and the Role of Diaspora.

DOI: 10.5220/0008820702950301

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs (ICoCSPA 2018), pages 295-301

ISBN: 978-989-758-393-3

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

295

percent) and communications (4 percent) (see Graph

1).

Graph 1: The composition of the services sector in India in

1990

Uniquely, the development of India's information

economy occurred in the midst of the availability of

human capital, which can be said to be limited. Data

from Papola and Sahu (2012) noted that in 1972 to

1973 alone, 74% of Indians still worked in

agriculture. Data from the Selected Education

Statistics (Bag and Gupta, 2016) suggested that up to

1983, only four per cent of Indians were in high

education. Not only regarding quantity, but most of

those in higher education were mostly the driving

forces in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors.

In the research of Banerjee and Muley (2008), which

mapped out the majority of engineering graduates in

India up to 1990, it was dominated by mechanical

and civil engineering with a growth rate of 17,696

and 13,546 graduates. On the other hand, computers

and IT techniques showed a growth rate of 12,143

graduates. This shows us the picture that the output

of the human resources produced by India are

commonly those with quality and capabilities

outside of the IT sector. In other words, the

capabilities, abilities, and levels of knowledge and

skills possessed by the majority of the workforce in

India are not strong enough to create a breakthrough

into the information economy.

Based on this exposure, it can be seen how there

is awkwardness and a certain uniqueness when

looking at the development of the information

economy in India. Theoretically, the information

economy is a knowledge-based and capacity-based

economy that requires the foundation of the

modernization of infrastructure that supports the IT

sector, through the collection of human capital with

special skills and knowledge as a driver of the

information economy (Castells, 1996). This

phenomenon then underlies the researcher's interest

in analyzing what important aspects enable India to

jump to the stage of having an information economy

and the manufacturing and industrial stages. The

uniqueness of this phenomenon also lies in how the

experience of India is different from that

experienced by Western and East Asian countries in

its economic development, which passed through the

first manufacturing stage. From this brief

explanation, it can be underscored that India seems

to have found a way to address the issue of its

human capital needs, making it interesting to further

examine India's economic information relationship

with the issue of human capital. In connection with

these findings, the question arises that the

information economy in particular requires human

capital oriented to specialized aspects of IT. How is

the development of the information economy

possible in India? How does India address the

critical human capital needs of this relationship? To

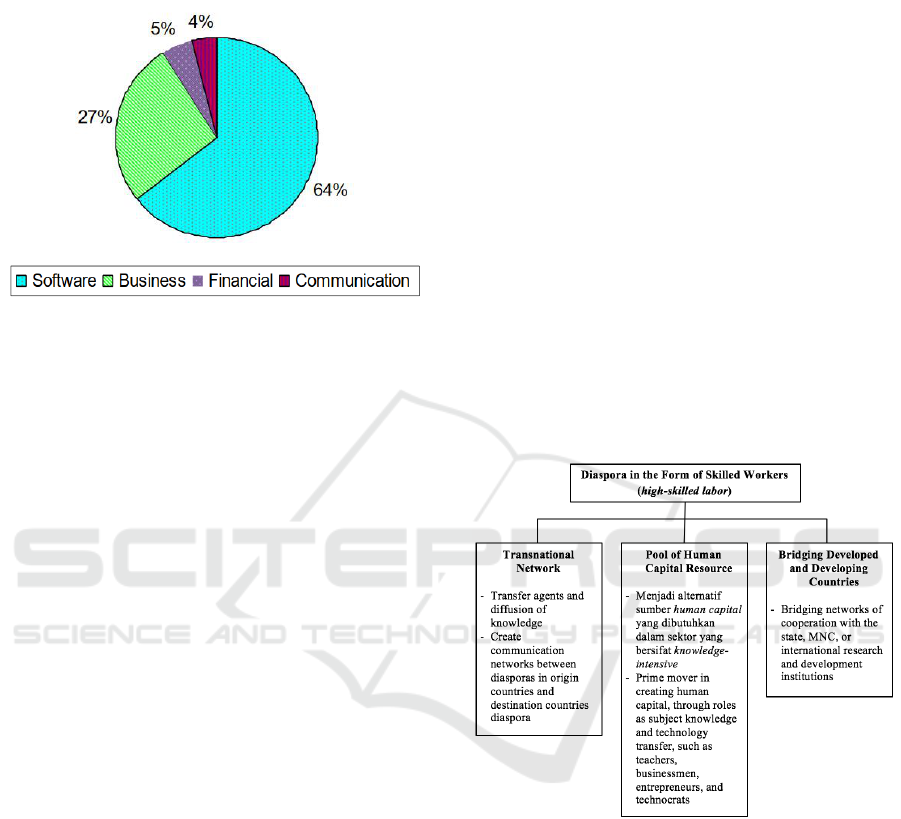

answer the question, the author used a diaspora role

approach to state the development, which can be

mapped into three:

Figure 1. The role of diaspora in the development of the

information economy (Source: Author analysis)

From this approach, in general, the hypothesis of

this study can be formulated as follows:

The key to the successful development of the

information economy in India is generally

related to its success in addressing the

problem of human capital needs and

The crucial role behind India's success in

relation to addressing the human resource

issues is India's creativity in exploiting and

developing the role of diaspora.

ICoCSPA 2018 - International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs

296

2 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

2.1 India and the Development of the

Information Economy

To explain how the Indian diaspora play an

important role in the IT sector-oriented economic

development process, it is important to first discuss

economic developments in India and how the IT

sector can emerge, and grow rapidly in countries that

theoretically should still be in industrialization. It

will be demonstrated by looking at the modern

technological advancements in India from the

beginning of independence and how, at first, the

agricultural revolution became the main reference of

technological development in India. Besides that,

this study will also explain what momentum was

able to encourage the IT sector through the industrial

revolution to becoming a major sector in India. This

chapter also explains the driving factors involved in

India's economic movement toward the IT sector in

a relatively short period of time.

One manifestation of the realization of the

information economy in India is the development of

the Indian Institute of Technology, through India's

national policy of the IIT Act in 1961. This

investment is a collaboration between the Indian

government and the US government. The role of the

US as a collaborator in the development of the first

wave of human capital makes IIT an important

institution in the creation of qualified computer

engineers. However, the IIT also has no significant

impact on human resources in India. The limited

number of human capital can be seen in the number

of graduates produced by the computer engineering

institute in India, which have only produced B.Tech

(650 graduates), M.Tech (S2 equivalent) as many as

800 graduates, and 60 Ph.D graduates. Banerjee

(2008) said that in the 1970-1985 period, India was

projected to have a deficit in the number of

graduates in engineering and computer science. It

can be seen that regardless of the policies and policy

orientation, India has begun to promote the

development of the IT-based education sector. In

reality India has serious obstacles in the way of its

realization. This is because the number of graduates

generated in India is not enough to push the mobile

IT sector into being the dominant economic power

in India. In the midst of an Indian situation requiring

human capital to develop an information economy,

Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, in the 1980s,

implemented a policy of tax reduction and intensive

development in the information economy sector.

This suggests that this need, in some cases, has been

bridged by the Indian government.

2.2 Rajiv Gandhi's Role in the

Development of India's

Information Economy

Under Rajiv Gandhi, India, which previously

focused solely on agricultural and industrial

economics, then began to look toward the IT sector.

To support the development of the IT sector, Rajiv

Gandhi devised three key policies aimed at building

the preconditions and infrastructure needed by India

to reach the economic stage of Information. This

policy was made by the Government of India under

Rajiv Gandhi, with the help of Sam Pitroda and

Narasimaiah Seshagiri. Starting from this

description, Rajiv Gandhi sought to design a foreign

policy that maximized the role of the IT sector in

India, that opened the technology transfer network

gateway, and that maximized the role of Indian

diaspora as the prime mover. This made the Indian

government under Rajiv Gandhi the first to

emphasize policies for the IT sector, electronics,

software, and telecommunications.

There are three major policies in the Rajiv

Gandhi era that were considered to have

revolutionized the IT world in India, as well as being

a magnet that draws Indian diaspora back to their

home countries, namely the Computer Policy 1984,

the Software Policy 1986, and the Software Garden

India India 1988. The Computer Policy 1984

downgraded PC software and tasks, and allowed the

import of computers in exchange for the export of

low tax software. The 1984 Computer Policy also

reduced the software import tariff from 100 percent

to 60 percent. In just one year after the policy came

into force, it was noted that computer production in

India increased by 100 percent, while computer

prices dropped by 50 percent (Athreye, 2005). The

1986 Software Policy provided access to

technologies and software in order to enhance their

global competitiveness and to promote high value-

added exports (Athreye, 2005). Therefore, the

import of software in any form is permitted and the

various procedures involved are simplified. The

policy also invites foreign investment and provides

venture capital to encourage the establishment of

new companies and export growth.

All three of these policies are rapidly changing

the information economy environment and thus, the

Indian IT industry, enabling domestic players to

demonstrate their capabilities in the IT sector and

thus to become viable alternatives for multinational

Development of the Information Economy in India and the Role of Diaspora

297

corporations that seek to invest in India. The policy

Software Technology Parks of India 1988 shows that

India is aware of the key factors of infrastructure and

the availability of IT sector incubation centers in

relation to building the information economy.

Multinational companies within the STP area are not

required to nationalize such a manufacturing sector,

and may be wholly foreign-owned and exempt from

export duties. From the description, generally it can

be concluded that in the effort involved in

developing the information economy, there are

obstacles that have arisen, namely the need for

human capital.

2.3 Indian Diaspora and the Role of

Human Capital

In this chapter, we will explain the mapping and

dynamics of the second wave of Indian diaspora,

which appears in many developed countries.

According to the Indian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

data in 2016, there are around 30.8 million Indian

diasporas. India has the largest diaspora population

in the world with more than 15.6 million according

to the United Nations Department of Economic and

Social Affairs (2015). Interestingly, the Indian

diaspora apparently showed a distinct trend after

independent India, favoring advanced post-industrial

countries as their goal. The diaspora that emerged

after Indian independence were referred to as the

second wave of the diaspora, and many chose to go

to the United States after the 1965 Immigration Act

was passed in the US and the state quota for

immigrants was abolished. This allows the Indian

diaspora to get permanent residence and to bring

their family members. It is interesting then to see

what underlies the number of diaspora who choose

developed countries as their goal.

2.4 Indian Diaspora in US

As one of the most recent and up-to-date IT

innovation centers, the US is a key destination for

Indian diasporas looking to pursue an education and

career in IT and computer engineering. Since the

beginning of the 20th century, the US has been

known as a center of computer innovation and is

believed to be the birthplace of computer

technology. The occurrence of the computer boom

throughout the late 1950s to 1960s led to many

companies becoming engaged in the field of

computers and software. The rise of the IT industry

in the US was also followed by the inclusion of the

Computer Science course at MIT as part of the

Electrical Engineering program in 1963. Similar

majors were also emerging in various other US

universities and it became one of the majors that US

aspiring students wanted. The existence of an

educational container in computer science and

engineering eventually became the main appeal for

Indian diasporas who wanted to continue their

studies in that field. In addition to the existence of

the latest computer boom and innovations in the US,

this diaspora saw the existence of career and

business prospects in the field that they did not

encounter in India at the time.

2.5 Contribution of Diaspora in the

Development of the Information

Economy in India

This proactive approach began to work when,

throughout the late 1970s and the 1980s, diaspora

began to emerge in India and provided the new IT

sector needed for its resurrection. To then see how

this brain-reinforcement process was slowly taking

place, the author has mapped out and illustrated the

contributions made by Indian diasporas returning to

India toward development in the IT sector.

The mapping of this contribution will

qualitatively be in the form of data that represents

how the diaspora returned to India, transforming

itself into the architect behind the IT sector's main

foundation. From the data and through case

examples of diaspora contributions to the

development of the IT sector as described, it can be

seen that there has been a significant contribution

from the Indian diaspora regarding the development

of India as a country with an information economy.

This can be seen in how the diaspora played a role in

the crucial moments involved in the rise of the IT

sector in India throughout the 1980s. Starting from

Sam Pitroda's role in the telecommunications

revolution and internet communication network in

India, through R.K. Baliga and Sharad Marathe with

the concept of the Electronic City and Software

Technology Park that became the forerunner of the

Indian Silicon Valley, through T.K. Rao who made

Texas Instruments the first multinational IT

company in Bengaluru and ending with Azim

Premji, who was the mastermind behind one of

India's IT giants. They are all Indian diaspora who

pursued their education and careers outside India,

who then returned to their home country and became

the initiator of IT sector development.

ICoCSPA 2018 - International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs

298

2.6 The Missing Intercourse: The

Development of the Information

Economy and the Role of Diaspora

This chapter will present an analysis and verify the

diaspora's role hypothesis in terms of developing key

points in the IT sector in India that occurred over a

relatively short period of time. The analysis begins

with a review of the IT sector’s development issues

in developing countries. This was followed by a

problem review for India. After that, the discussion

continued in order to discuss the extent to which

diaspora can be the actor that becomes a solution to

the problem of developing the IT sector in a given

country. In the end, the subject focuses on how

Indian diaspora came in response to the problems

and become actors who began the process of

developing India's information economy.

First, the diaspora have the potential to become a

stronger transnational link between the diaspora and

the diaspora's home country. According to Safran

(1991), the diaspora tend to involve their homeland

early and with greater dedication than non-ethnic

investors. This is because the diaspora underlies

their actions with sympathy and solidarity. Second,

the interaction between diasporas and domestic

actors tends to be more reliable and lasting, and this

is called a trust network. A trust network is defined

by Tilly (2007) as a good network of interconnecting

relationships between diasporas and communities in

their home countries that facilitates the transfer of

ideas and resources from the outside to the domestic

actors. This is because the proximity of a shared

culture, history, and language that makes it easy for

the diaspora to be trusted by their country of origin.

Good relationships facilitate the transfer of ideas and

resources from the outside to the domestic actors.

Third, diaspora networks help to overcome

institutional and infrastructure constraints and

reduce transaction costs in investing in undeveloped

homeland markets (Chen and Chen, 1998). With

linguistic similarities and the knowledge of local

norms, diaspora are more likely to involve local

officials and economic actors. Support at the

domestic level can enhance economic liberalization

(Hsing, 1998).

Diaspora in the category of high-skilled workers

can also be a major actor in the process of the

transfer of technology and knowledge from

developed countries into their home country. The

process of technology transfer and knowledge

occurs when diasporas have been educated in

developed countries and return back to their home

countries, often becoming educators, businessman,

entrepreneurs and technocrats who are the main

drivers of the process of creating human capital and

forwarding the economic development of the

country (Saxenian, 2005). In many situations, the

diaspora also pave the way for the inclusion of

multinational companies and international research

and development institutions in their home

countries. This is possible because diaspora play a

role in bridging the link, allowing for collaborations

between the state and multinational corporations, as

well as international research and development

institutions as the subject of knowledge and

technology transfer (Saxenian, 2005). In other

words, the diaspora also have an indirect role as an

actor who opens the door of cooperation and who

inhibits the inequality of science, technology and

human capital between their home country and the

destination country.

Diaspora also help local entrepreneurs enable

economies in their home countries to participate in

the information economy (Saxenian, 2005). Their

professional network can quickly help to build

promising opportunities, raise capital, build

management teams, and build partnerships with

manufacturers in other parts of the world. The ease

of exchanging communication and information in

the network is localized by freedom, technology, and

the discussion of new skills, technology and capital,

as well as potential investors (Saxenian, 2005).

There are three roles underlying the rise of India's

information economy. In general, the diaspora

depiction becomes a bridge and an important link in

the economic view of information.

The explanation of this study is that an important

issue in India's information-economic development

efforts related to inadequate human capital can be

domestically produced by India to solve the urgent

need for human capital. The possible path for India

to build its IT sector and its information economy is

through diasporas. This is motivated by the absence

of significant efforts by India in relation to the

accumulation of human capital through the means of

applying for foreign workers or through the reform

and implementation of effective educational

policies. Therefore, diaspora have three major roles

in the development of the state. By pulling diaspora

back into the high-skilled worker category, a brain

reinforcement situation will occur and the problem

of human capital needs in India can be bridged.

Diaspora, when in the context of the

development of the information economy, serve as

an important link in the process of developing the

information economy. Through its three roles, the

diaspora can act as an important linking thread for

Development of the Information Economy in India and the Role of Diaspora

299

knowledge transfer, changing the mapping of

multinational corporations as key actors in the

transfer of knowledge at the global level. Many

diasporas return to India to start their own

businesses and to create forums for information

exchange. They also advise the country's

development authorities. Besides that, diaspora also

play a major role in bridging various state benefits,

such as remittances and FDI flows that are of

international importance for the knowledge transfer

process.

3 CONCLUSIONS

In general, India is experiencing a shortage of

human capital suitable for a larger revolutionary

information economy under Rajiv Gandhi's

government. In the period 1984-1990, India

succeeded in making the information sector one of

its major sectors and revolutionized the information-

related policies in India, especially in the aspects of

software production and exports. This occurred in

central India, which was visited by human resources

to encourage the information economy sector. This

led to a potential discussion of the diaspora as a

source of human capital. In connection with the

situation of Indian diaspora emigrating out of India,

they are a group that has a high level of education

and that are a part of the skilled workforce. The data

found showed that diaspora have a high interest in

the IT sector in the destination countries, which is

dominated by the US. This is evident from the

number of Indian students at MIT who occupy one

of the largest numbers of diaspora students and in

the high number of Indian diaspora involved in the

Silicon Valley region.

This caught the attention of PM Rajiv Gandhi,

who sought to attract the diaspora. Through his

initiative, Rajiv Gandhi succeeded in attracting

important figures such as Sam Pitroda, T.K.Rao,

Azim Premji, and Sharad Marathe. Accompanied by

three revolutionary policies - the 1984 Computer

Policy, the Software Policy 1986, and the India

Software Software Park of 1988 - India quickly

succeeded in revolutionizing their economic

conditions into an information economy. Not only

that, the diaspora called by Rajiv Gandhi also

initiated the construction of important points in

India's information economy sector. Using the

outlined framework, it can be confirmed that the

main findings in this study are: (1) that India has

proven successful in addressing human capital needs

in an effort to build the information economy in a

short time and (2) that diaspora are the answer to the

needs and proven problems, and that they have a

significant role and contribution to India's

development of the information economy.

Therefore, it can be concluded that India, in a short

time, succeeded in building its information economy

and addressed the problem of human capital needs.

The diaspora are the chain and the answer to the

cause of the development of India's information

economy. In this case, the diaspora served as an

alternative source of human resources required by

the information economy in India, and they

contributed to the information economy in India

through the initiation of technology transfer, the

source of knowledge and the human resources that

foster the development of sectors related to the

information economy. They serve as a bridge

between their home country and the global

economy.

REFERENCES

Arora, A, Arunachalam, VS, Asundi, J, and Fernandes, R.

(2013). India’s Software Industry, Unpublished

manuscript, Heinz School, Carnegie Mellon

University.

Athreye, S. (2005). The Indian software industry, Working

Paper, The Open University.

Bag, S and Gupta, A. (2016). Performance of Indian

Economy during 1970-2010: A Productivity

Perspective. The Indian Economic Journal.

Banerjee, UK. (2008). Computer Education in India:

Past, Present, and Future.

Banerjee, R and Muley, VP. (2008). Engineering

education in India, draft final report. Sponsored by

Observer Research Foundation; Energy Systems

Engineering. IIT Bombay Powai: Mumbai.

Chen, H and Chen TJ. (1998). Network linkages and

location choice in FDI. Journal of International

Business Studies, 29 (3):445–467.

Eichengreen, B and Gupta, P. (2010). The service sector

as India’s Road to economic growth?. Indian Council

For Research on International Economic Relations, 1

(1):18.

Hsing, YT. (1998). Making Capitalism in China: The

Taiwan Connection. New York: Oxford University

Press.

NASSCOM (2001) The IT Software and Services Industry

in India. New Delhi: NASSCOM.

NASSCOM (2002) IT Industry in India – Strategic

Review. NASSCOM. New Delhi: NASSCOM.

NASSCOM (2003) IT Industry in India – Strategic

Review. NASSCOM. New Delhi: NASSCOM.

NASSCOM (2004) IT Industry in India – Strategic

Review. NASSCOM. New Delhi: NASSCOM.

ICoCSPA 2018 - International Conference on Contemporary Social and Political Affairs

300

NASSCOM (2005) IT Industry in India – Strategic

Review. NASSCOM. New Delhi: NASSCOM.

Papola, TS and Sahu, PP (2012) Growth and Structure of

Employment in India: Long-Term and Post-Reform

Performance and the Emerging Challenge, Structural

Changes, Industry, and Employment in The Indian

Economy.

Safran, W (1991) Diasporas in modern societies: Myths of

homeland and return. Diaspora: A Journal of

Transnational Studies, 1:83–99.

Saxenian, A (2005) From Brain Drain to Brain

Circulation: Transnational Communities and Regional

Upgrading in India and China. Studies in Comparative

International Development, 40:35-61.

Tilly, C (2007) Trust Networks in Transnational

Migration. Sociological Forum, 22 (1):7.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social

Affairs (2015) International migrant stock 2015:

Graphs: Twenty countries or areas of origin with the

largest diaspora populations (millions).

Development of the Information Economy in India and the Role of Diaspora

301