Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale:

Ps

y

chometric Evaluation of the Indonesian Version

Anindya Dewi Paramita

1

, Andi Tenri Faradiba

2

and Puti Febrayosi

2

1

Faculty of Psychology, University of Pancasila, Srengseng Sawah, Jakarta, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Psychology, Center of Psychological Measurement, University of Pancasila, Srengseng Sawah, Jakarta,

Indonesia

Keywords: Postpartum depression, Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), psychometric evaluation

Abstract: Childbirth is a life-changing event. If the mothers are not able to adapt, major problems will arise and can

lead to depression. The Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) was the most popular screening

tools for detect the main symptom of depression in postpartum period. Developed by Cox, Holden &

Sagovsky (1987), now the EPDS has been translated into several languages such as France, Hebrew,

Swedish, Bangla, Chinese, including Indonesian. However, no one has published a comprehensive

psychometric evaluation of the Indonesian version of EPDS. The aim of this study was to investigate the

validity and reliability of the Indonesian version of the EPDS. A two-stage design was used in this study.

Stage I consisted of a process of translation and back-translation by language experts and compare it with

the original version. Stage II established the psychometric properties of the EPDS by examining the validity

and reliability of the scale using content validity index suggested by Lynn (1986) and internal consistency

using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Stage III examine the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to explore the

best model of postpartum depression measurement. The result shows that EPDS is a good tool to measure

postpartum depression in Indonesia.

1 INTRODUCTION

Childbirth is a huge milestone for every mother and

changes almost every aspect of their lives. Those

processes, starting from pregnancy, childbirth until

postpartum period cause physical, psychological and

social changes that may lead to stress (O’Hara,

1995). During postpartum period, the reproductive

organs was trying to return to their non-pregnant

state, which takes time about six weeks (Gjerdigen,

Froberg, Chaloner, & McGovern, 1993). For many

women, recovery from childbirth may experienced

discomfort for weeks, some face more serious

problem that may limit their daily function for some

time. They also need to adjust their way of life,

including disrupted sleep and daily routines which

can be challenging for mothers especially first timer

(Choudhury, Counts & Horvitz, 2013). When they

fail to manage those changes, new problem will arise

and they may end up depressed. According to Venis

& McCloskey (2008), some symptoms that

depressed mothers experience after childbirth are

mood swings, easily gets angry, fatigue, lost interest

to do daily and even sexual activities, trouble

sleeping and eating, and sometimes having thoughts

of harming themselves or their baby, that can occur

during the first two weeks after birth. This disorder

is called Post Partum Depression (PPD). In some

cases, mothers who had PPD had suicidal thoughts

or tendencies (O’Hara, 1995). This symptoms can

occurred since pregnancy until more than one year

after childbirth (Clark, Tluczek, & Wenzel, 2003;

Blum, 2007).

To prevent those mothers suffering from

postpartum depression, some professionals develop

a tool to detect depressive symptoms from mothers

after birth. One of most popular and widely used

tools to screen PPD is the Edinburgh Postpartum

Depression Scale (EPDS). The EPDS is a 10-item

self-rating scale designed to identify postpartum

depression (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987). Since

then, several studies was conducted to validate and

translate this tool into several languages, such as

Frenchs, Hebrew, Bangla, Chinese, including

Indonesian (O’Hara, 1995). Eventhough the EPDS is

still commonly used as a research tool or for

professional purposes, its validity and reliability

410

Paramita, A., Faradiba, A. and Febrayosi, P.

Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale: Psychometric Evaluation of the Indonesian Version.

DOI: 10.5220/0008590204100414

In Proceedings of the 3rd Inter national Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS 2018) - Improving Mental Health and Harmony in

Global Community, pages 410-414

ISBN: 978-989-758-435-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

have been poorly studied until now. The aims of the

present study are to assess the validity and reliability

of the Indonesian version of EPDS and to find

practical recommendations of the EPDS tool

development.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this section we will explain the process, materials,

and plans of our research from the very beginning

until we examine the data.

2.1 Translation

A translation of the original EPDS into Indonesian

was followed by back-translation into English. Two

psychologists translated the questionnaire into

Indonesian and two professional translators

backward translated these into English. Then the

provisional version of the Indonesian questionnaire

was developed and pilot tested. The final version of

the questionnaire was developed after considering

few suggestions from pilot data.

2.2 Sample and Data Collection

The Indonesian version of the EPDS was

administered to mothers who had a baby under age

12 months. The samples were recruited from several

health care centres in Jakarta, Bogor and Depok

during they postnatal routine check-up or their

babies’ monthly visit to the health care. 252

mothers were included in this study. The entire

participant in this study agreed to participate with

signing the informed consent and brief explanation

of the study given to them before we delivered the

questionnaire.

2.3 Measure

The EPDS consists of 10 items and each item is

rated on a four-point scale (0 to 3), giving maximum

scores of 30. This scale covers common symptoms

of depression. It excludes somatic dimensions such

as fatigue and appetite variations which are normal

during the ante- and postnatal periods (Adouard,

Glangeaud-Freudenthal, & Golse, 2005). In short,

the 10 items measured depressive symptoms (“I

have been so unhappy that I have been crying”),

anxiety (“I have been anxious or worried for no

good reason”), and anhedonia (“I have looked

forward with enjoyment to things”). The original

EPDS has a 12.5 cut-off point that showed that score

13 and up indicates major postpartum depression,

but along the way research showed that the cut-off

point varies from one research to another, range

from 9 to 12.5. According to Cox, Holden &

Sagovsky (1987), a score from 0 to 9 indicated ‘not

depressed’, while scores of 10 to 12 represent

‘borderline’ and a score 13 or more is considered

postnatal depression.

2.4 Procedure

All subjects were recruited when coming for a

postnatal check-up or monthly visit for their baby’s

vaccination at the health care services. Each woman

was then asked by researcher to participate in this

study. After hearing the explanation about the

purpose of this study, reading the agreement and

signing a written informed consent, women who

agree to participate were asked to complete the

demographic data questionnaire and the EPDS.

2.5 Psychometric Properties

We examined content validity of the EPDS’s items

with Content Validity Index (CVI). According to

Lynn (1986), there are two types of CVIs. The first

type is content validity of individual items (I-CVI)

and the second is content validity of overall scale (S-

CVI). In order to examine CVI, three experts were

recruited to evaluate the relevance of the items and

the overall scale of Indonesian EPDS. We asked all

of the experts to rate each item’s relevance to

postpartum depression in a 4-point scale

questionnaire. Then, for each item, the I-CVI is

computed as the number of experts giving a rating of

either 3 or 4, divided by the total number of experts.

To examine the S-CVI, we are looking for the

proportion of items given a rating of quite/very

relevant by raters involved. We also measure item

validity using inter-item correlation. Reliability was

estimated by measuring internal consistency with

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient from the EPDS score.

We also performed a factor analysis of the EPDS to

investigate its internal structure.

2.6 Statistical Methods

Item validity was computed using Pearson

correlation. Internal consistency was performed

using Cronbach’s α with Statistical Package for

Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 for Windows.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted

using Lisrel 8.7.

Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale: Psychometric Evaluation of the Indonesian Version

411

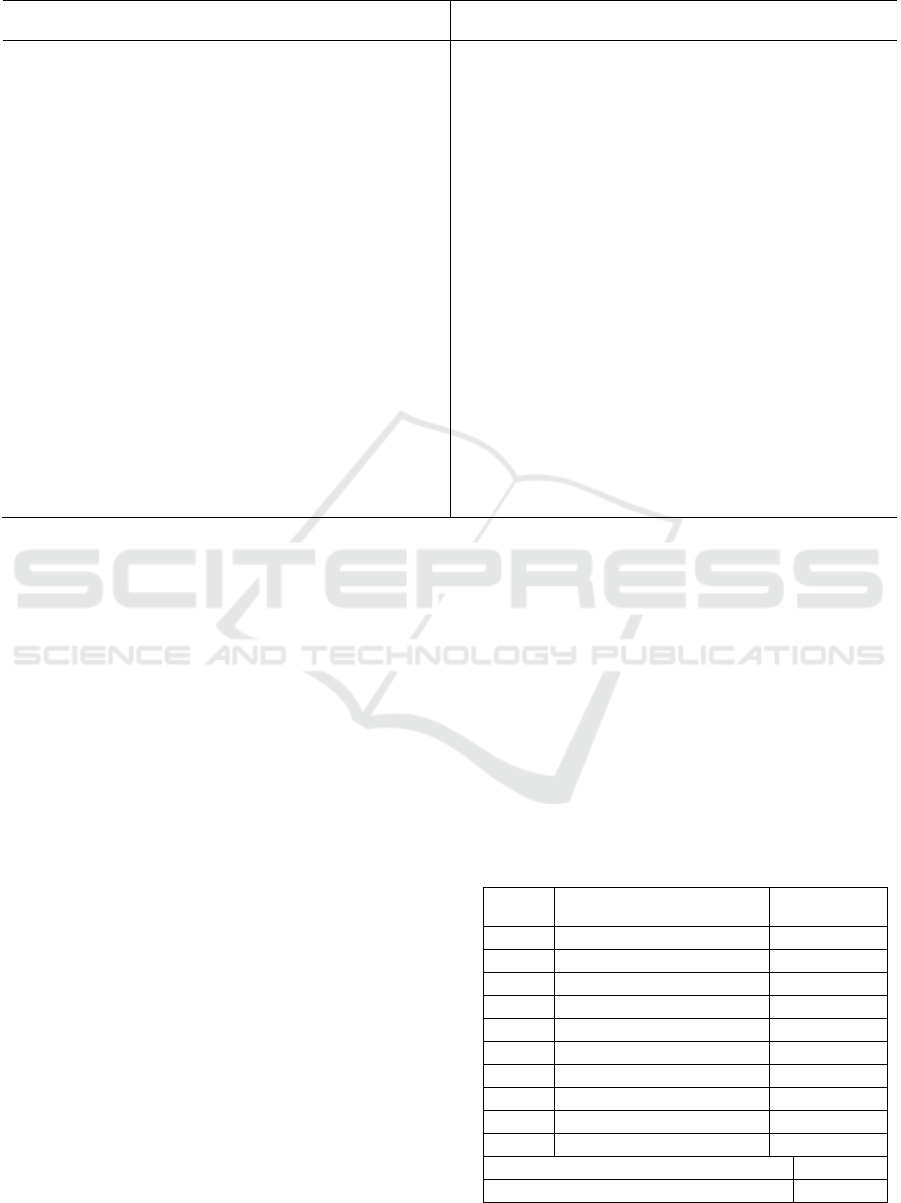

Table 1: The Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale

Original Version Translated Version

1. I have been able to laugh and see the funny side

of things.

2. I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things

went wrong

3. I have felt scared or panicky for not very good

reason

4. I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty

sleeping

5. I have been so unhappy that I have been crying

6. I have looked forward with enjoyment to things

7. I have been anxious or worried for no good

reason

8. Things have been getting on top of me

9. I have felt sad or miserable

10. The thought of harming myself has occurred to

me

1. Saya bisa tertawa dan melihat sisi lucu dari

segala sesuatu

2.

Saya bisa tertawa dan melihat sisi lucu dari

segala sesuatu

3.

Saya menjadi lebih mudah panik atau merasa

takut tanpa alasan yang jelas

4.

Saya merasa tidak bahagia sehingga kesulitan

tidur

5.

Saya merasa tidak bahagia sehingga seringkali

menangis

6.

Saya lebih optimis dan gembira dalam melihat

hal-hal yang saya alami

7.

Saya merasa cemas dan khawatir tanpa ada

alasan yang jelas

8.

Segala sesuatu terasa sulit untuk saya kerjakan

9.

Saya merasa sedih atau sengsara

10. Pikiran untuk menyakiti diri saya atau bunuh diri

pernah terlintas dalam benak saya

3 RESULTS

Content Validity Study

Before finalizing the questionnaire, we pilot tested it

to some mothers who had experienced childbirth in

order to find out the readability of the items for

them. For face validity, the mothers found that the

EPDS is acceptable and easy to complete. They also

said that they able to understand what were the

meaning of each items. Then we asked three experts

to rate our item and overall scale’s relevance to

postpartum depression to examine the Content

Validity Index (CVI). There is a clinical

psychologist who had experienced at handling

depressed mothers, an obstetrician/gynaecologist,

and a nurse. According to Lynn (1986), each expert

is asked to rate the items on a 4-point ordinal scale

(1= not relevant, 2 =quite relevant, 3 =relevant, 4

=highly relevant). Then, for each item, the I-CVI is

computed as the number of experts giving a rating of

either 3 or 4. An item is categorized as relevant if all

of the experts are agree to rate the item 3 or 4. To

know the S-CVI, we computed the proportion of

items that rated 3 or 4 by the experts.

From the experts’ rating, we found out that all of

the items get the agreement from all the raters. The

S-CVI was 1.00, meaning that 100% of the total

items were judged content valid. Qualitatively, all

three experts gave suggestions related to the item’s

wording to item number six (“I have looked forward

with enjoyment to things”) and number eight

(“Things have been getting on top of me”). Based on

the input from the experts, we need to adjust the

linguistic structure and use of words to make the

items’ readability better and avoid the participants

get confused. Then we revised both items according

all of the suggestion and then pilot tested the EPDS

to the participants.

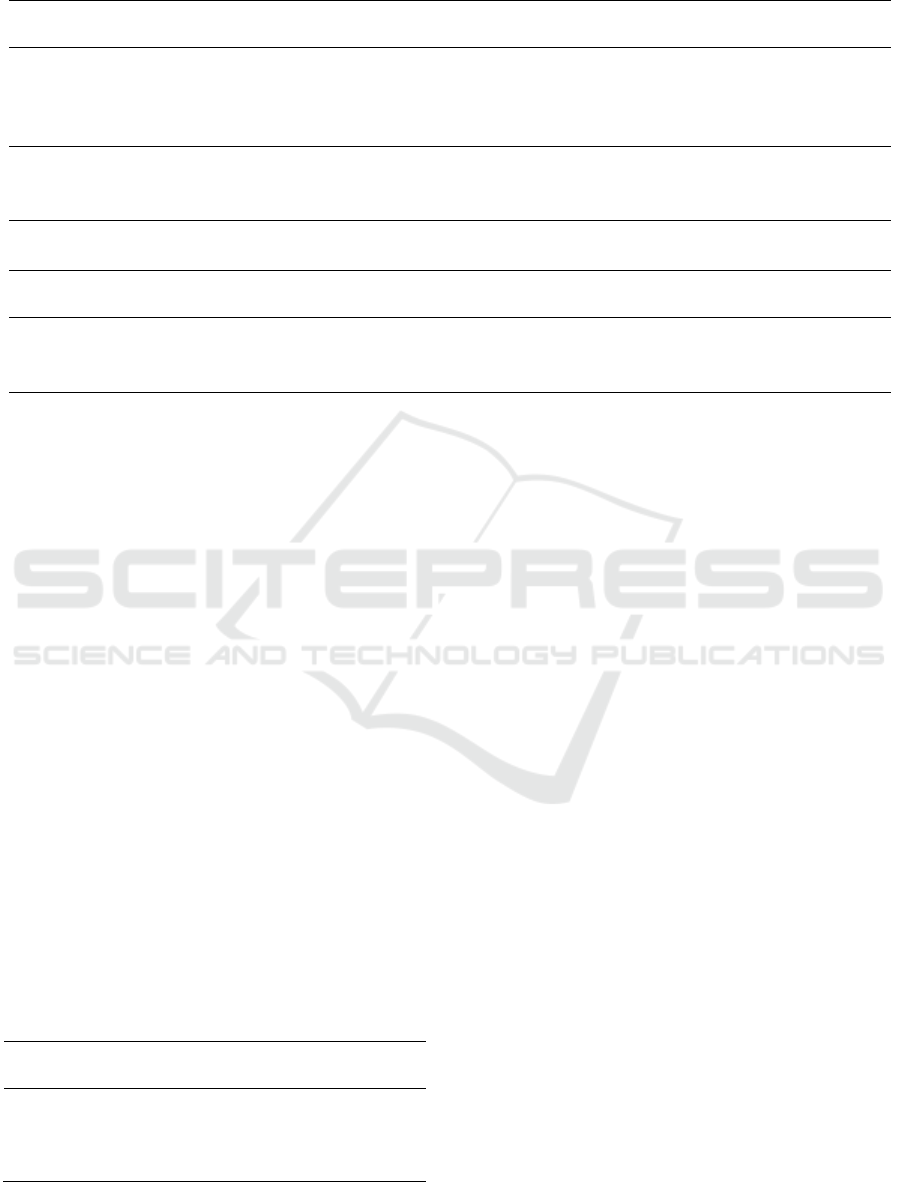

Table 2: Computation of I-CVI and S-CVI of the

EPDS with three expert raters

Item Number in Agreements Item CVI

13 1

23 1

33 1

43 1

53 1

63 1

73 1

83 1

93 1

10 3 1

Mean I-CVI = 1,00

S-CVI = 1,00

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

412

Tabel 3: Factor Loading Postpartum Depression – second order unidimensional model

Dimension Item

Factor Loading

Coefficients

Std. Error T-value Notes

Depression

ITEM-4 0,657 0,050 13.128

ITEM-5 0,698 0,047 14.878

ITEM-9 0,708 0,053 13.467

ITEM-10 0,684 0,078 8.820

Anxiety

ITEM-2 0,535 0,059 9.113

ITEM-3 0.651 0,054 12.068

ITEM-7 0.631 0,061 10.421

Anhedon

ITEM-1 0.434 0,109 3.993

ITEM-8 0.471 0,102 4.625

Factor Dimension

Factor Loading

Coefficients

Std. Error T-value Notes

Postpartum

Depression

Depression 0.963 0.068 14.098

Anxiety 0.812 0.071 11.499

Anhedon 1.184 0.228 5.190

Reliability Study

Reliability was estimated by the measure of the

internal consistency using the Cronbach’s alpha

coefficient. The internal consistency assessed for the

global EPDS scale was 0.706.

Factor Analysis Study

Our factor analysis suggests that a three factor

model would be better fit than a unidimensional one.

In Touhy and McVey’s (2008) confirmatory

analysis, three factors were found; which were

identified as ‘non-specific depressive symptoms’

(items 4, 5, 9, 10), ‘anhedonia’ (items 1, 6, 8) and

‘anxiety’ (items 2, 3, 7). Based on the first order

unidimensional model, item number six was found

not valid since its inter-item correlation is zero,

which means this item is not clearly measure the

dimensions it wants to measure. Construct validity

measurement shows that the P value > 0.05 and

RMSEA < 0.050. This means that postpartum

depression model second order unidimensional was

fit with the data. The P value index and RMSEA will

be presented in table below:

Tabel 4: Model fit criterion – EPDS second order

unidimensional

Model Fit

Criterion

Model Fit Index

Chi Square 31.049

P Value 0.1524

RMSEA 0.034

CFI 0.988

4 DISCUSSIONS

Our study confirms that this Indonesian version of

EPDS is a good tool for screening depression after

childbirth in mothers, in line with the conclusion of

some previous studies on EPDS validations (Cox,

Holden & Sagovsky, 1987; Adouard dkk., 2005).

There are some limitations must be considered along

the research process. Although it has pretty good

face validity for the mothers, result shown that this

Indonesian EPDS has one item classified as not

valid, that is item number six. CVI, inter-item

correlation and factor analysis proofed that item

number six is not good enough to measure

depression. Based on the suggestions the experts

gave upon item number six, we need further research

to retest the revised and reviewed version of item

number six. We assumed that it might be related

with the diction used to make translated version of

item six that is not fit with the cultural values and

way of living of Indonesian people.

For further research, there are some things that

we have to explore more about EPDS in Indonesian

language, such as the sensitivity of the cut-off score,

broaden the number and diversity of the sample, and

try to explore the concurrent or discriminant

evidence to continue the validation study.

Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale: Psychometric Evaluation of the Indonesian Version

413

REFERENCES

Adouard, F., Glangeaud-Freudenthal, N. M. C., & Golse,

B. (2005). Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal

depression scale (EPDS) in a sample of women with

high-risk pregnancies in France. Archives of Women’s

Mental Health, 8, 89-95.

Blum, L. D. (2007). Psychodinamics of Postpartum

Depression. Journal of Psychoanalytic Psychology,

24(1), 45-62.

Choudhury, M.D., Counts, S., & Horvitz, E. (2013).

Predicting Postpartum Changes in Emotion and

Behavior via Social Media. Paper presented at CHI

2013: Changing Perspective, Paris, France.

Clark, R., Tluczek, A., & Wenzel, A. (2003).

Psychotherapy for postpartum depression: a

preliminary report. American Journal of

Orthopsychiatry, 73(4), 441-454.

Cox, J., Holden, J., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of

postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal

of Psychiatry, 105, 782-786.

Cox, J., & Holden, J. (2003). Perinatal Mental Health: A

Guide to the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

(EPDS). London: Gaskel – The Royal College of

Psychiatrists.

Gjerdingen, D.K., Froberg, D.G., Chaloner, K.M., &

McGovern, P.M. (1993). Changes in Women's

Physical Health During the First Postpartum Year.

Archieve of Family Medicine, 2, 277-283.

Guedeney, N., & Fermanian, J. (1998). Validation study of

the French version of the Edinburgh Postnatal

Depression Scale (EPDS): new results about use and

psychometric properties. Eur Psychiatry, 13, 83-89.

Lynn, M.R. (1986). Determination and quantification of

content validity. Nursing Research, 35, 382–385.

O'Hara, M. W. (1995). Postpartum Depression: Causes

and Consequences. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Touhy, A., & McVey, C. (2008). Subscales measuring

symptoms of non-specific depression, anhedonia, and

anxiety in the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47, 153-169.

Venis, J. A., & McCloskey, S. (2008). Postpartum

Depression Demystified: An Essential Guide for

Understanding and Overcoming the Most Common

Complication after Childbirth. New York: Marlowe

& Company.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

414