Is Self-efficacy

R

elated to Students’ Moral

R

easoning?:

A Research on Students’ Absentee Behavior

Aurelius Ratu, Ni Gusti Made Rai, Niken Prasetya, and Dyah Satya Yoga

Sepuluh Nopember Institute ofTechnology, Keputih, Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: Self-Efficacy, Moral Reasoning, Deviant Behavior.

Abstract: Some previous studies on moral reasoning related to self-efficacy in an academic setting have reported

students widely held moral belief that they know very well what is morally wrong or good. Generally, a

student’s moral awareness is presumably taken for granted at a college. This tendency often evokes the

deviant-behavioral tendencies either because of internal or external factors. The aim of this study was to

examine a correlation between self-efficacy and moral reasoning on students’ absentee behavior. Through a

bivariate correlation analysis with 0.05 alpha level, the result showed that the higher self-efficacy the more

they could make reasoning on moral decisions and the more they could justify a wrong action in certain

situations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Students ethics beliefs have been the subject of

numerous studies (Lawson, 2004; LaDuke, 2013).

Moreover, some studies have been devoted to

understand this growing phenomenon and to identify

factors related to the student's ethics. But, there were

just a few efforts to understand the ethics belief and

self-efficacy (Farnese et al., 2011a). As noted, in an

academic setting, the amoral behavior is often seen

as ‘nothing to worry about' or ‘everyone was doing

it'. It even has been regarded as customary behavior.

This is precisely the problem. The moral aspects are

unconsciously separated from academic purposes.

This study tries to give emphasis on moral

engagement acknowledge that academic dishonesty,

trusting oneself’ presence, typically calls forth moral

standard (Thorkildsen, Golant and Richesin, 2007).

Concerning the moral aspect, though it was

intrinsically discussed, some researches have been

done to get to a better understanding of this problem.

One of these researches indicated that there is a

correlation between a competitive system in an

academic setting with cheating behavior (Anderman

and Midgley, 2004; Cartwright and Menezes, 2014).

Another research indicated that students with the

highest grade point average actually had cheated or

done plagiarism (Patall and Leach, 2015). Even,

some students believed that unethical behavior is

essential to advance careers (Lawson, 2004).

Some people have viewed the breaking of the

regulations when they were in the academic process

as something beneficial. This inconsistency clearly

raises a question on the implementation of a

standard moral in an academic setting. Whereas

academic achievement is considered one important

criterion of educational quality, moral problems

were often considered as a part of personal

responsibilities (Hakimi, Hejazi and Lavasani,

2011). It is the case we want to elaborate. If we talk

about the moral standard, we talk about how

students' moral judgments on specific circumstance

relating to their moral principles (Palmer, 2005). In

other side, students' moral principles are related to

what Bandura called it a self-organizing, proactive,

self-reflective, and self-regulative mechanism

(Bandura, 2002).

In this paper, we focus on whether self-efficacy

have a correlation toward moral reasoning. In the

context of moral reasoning, we use four attributions

as a part of neutralization theory consisting of denial

of responsibility, appeal to higher priority/value,

denial of the injury, and denial of the victim

(Murdock and Stephens, 2007).

Ratu, A., Rai, N., Prasetya, N. and Yoga, D.

Is Self-efficacy Related to Students’ Moral Reasoning?: A Research on Students’ Absentee Behavior.

DOI: 10.5220/0008590003970405

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS 2018) - Improving Mental Health and Harmony in

Global Community, pages 397-405

ISBN: 978-989-758-435-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

397

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Theory of Neutralization -

Reasoning on Moral Decisions

This theory is part of theory deviant behavior.

Neutralization theory states a person knows that the

action is morally objectively wrong. But, because of

reasoning, that action seemed right. It means that a

person tries to avoid the responsibility and to

decrease negative emphasis from oneself and the

others. These attempts came out of doing something

wrong morally.

This theory was developed from Kohlberg's

hypothesis and was introduced firstly by Sykes and

Matza who observed that there are the tendencies

one’s moral development through education and

experience is not followed by the application of

moral conduct in certain situations (Murdock and

Stephens, 2007b; Sykes and Matza, 1957). In other

words, this neutralization lessens negative

judgments made by oneself and the others for the

behavior. Commonly, this neutralization is also

called justifications which are viewed as following

deviant behavior and as protecting the individual

from self-blame and the blame of others after the

act.

The emphasis on moral aspects in this study

leads to what becomes a moral standard in an

academic setting. Moral aspects should be inherently

regularities of the college as positive law. However,

several factors such as motivation to achieve a better

GPA, environmental and friendship influences

caused the existing rules forceless. Some studies

found this phenomenon as an inconsistency between

academic attitude and the moral behavior

(Cartwright and Menezes, 2014; Hakimi, Hejazi and

Lavasani, 2011; Iorga, Ciuhodaru and Romedea,

2013; Lawson, 2004; Turiel, 2015). One of these

inconsistencies is the behavior of the absentee who

entrusts oneself’s presence to the others for avoiding

his/herself from the lack of absent percentage in

class. That behavior revealed how students

understand their moral principles but at the same

time, they can neutralize those principles for some

reasons.

Absentee behavior, trust oneself’ presence,

basically is not only concerning how moral

awareness is examined in an academic setting. It

also brings an understanding of how the students

believe their moral standard and acts on it.

Following neutralization theory, we use the

attribution theory to examine the absentee behavior,

i.e. denial of responsibility, the higher priority,

denial of the injury, and the denial of the victims.

This theory rests on assumption that everyone is

innately motivated to make sense of his or her world

particularly events that are negative, unexpected, or

not normative (Murdock and Stephens, 2007).

The first attribution is concerning how a person

can externalize responsibility. The second attribution

is concerning with capability of determining priority

scale. The third attribution is concerning with

capability of making an excuse for an illegal action

but morally not a wrong action. The fourth

attribution is concerning with capability of

transforming oneself into a victim of wrongdoing.

2.2 Theory of Self-efficacy

In an academic setting, self-efficacy was often

related to achievements either grade point average,

learning strategies, or even dishonest behavior

(Farnese et al., 2011b; Murdock, Tamera B. and

Murdock, 2006; Stajkovic et al., 2018). Self-efficacy

is the belief in self-capacity to drive one’s

motivation. It is also affected by cognitive aspects

and rises from the need to cope with specific

situations. Self-efficacy has some functions to

predict an important task concerning the work

behavior, the learning ability, and so forth. Based on

Bandura ’s social cognitive theory, self-efficacy has

three dimensions that of magnitude, strength, and

generality (Bandura, 1978; Bandura et al., 2001).

The first dimension is dealing with a level of

difficulties. The Second dimension is dealing with

the willingness to show the results from the

difficulty level of the task. The third dimension is

dealing with the belief in the task based on

experiences gained.

Furthermore, self-efficacy makes a person be

able to predict his future actions (Azizli et al., 2015).

The belief on self-capability will encourage a person

to adjust oneself in achieving the best results for the

future career. This self-capability even predisposes a

person to organize the strategies and the planning in

order to achieve the expected goals. But the moral

problems could emerge if orientation towards the

expected goals was not in accordance with the

regulations. In this study, self-efficacy could be a

moral justification in the sense that absentee

behavior is made personally and socially acceptable

by portraying it as serving socially worthy or moral

purposes. It even occurs when the students can act

on moral imperative and preserve their view of

themselves as moral agents while inflicting harms on

others (Bandura, 1978, 2002, 1999; Bandura et al.,

1996).

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

398

3 METHOD

3.1 Participants

Five hundred twenty-one students from 29

departments at Sepuluh Nopember Institute of

technology were asked to fill in a questionnaire. It

was done during the regular period of the learning

process. The data concerning gender, age, and grade

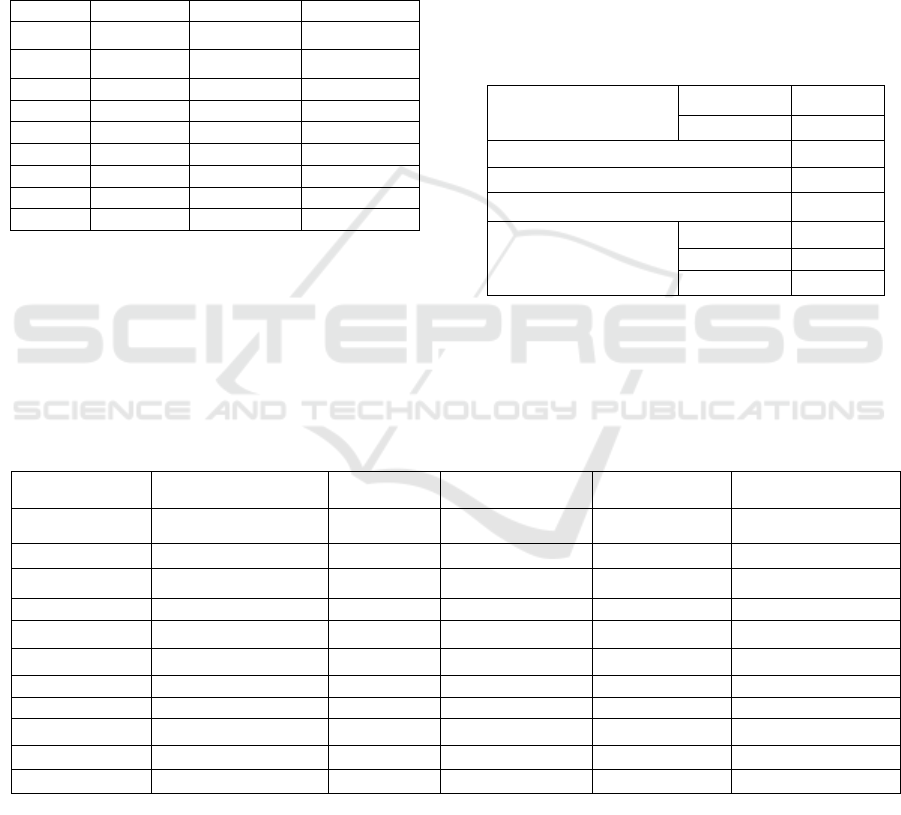

point average (GPA) is shown in table 1.

Table 1: Demographic Variables of the samples (N = 521).

Number* Percenta

g

e*

Gender Man 289 55,5

Woman 232 44,5

A

g

e 18-20 460 88,3

21-23 61 11,7

GPA <2.00 5 1,0

2.01-2.5 31 6,0

2.51-3.00 120 23,0

3.01-3.50 234 44,9

>3.51 131 25,1

Note: *Number and percentages based on cases with valid

responses

3.2 Measures

Self-efficacy was assessed by an 8-item Likert

Scale. Response option was provided in a five-point

format ranging from 1= strongly disagree to 5 =

strongly agree (Chen, Gully and Eden, 2001). All

statements of Self-efficacy were acceptable at 0,78

Cronbach's alpha for the validated scale. The

students were also asked to express their opinion

regarding self-perception during the academic

process. For the Likert scale’s result, we divided the

level of self-efficacy into quartiles as shown in table

2.

Table 2: Frequency Statistic from the total score on self-

efficacy (N=521).

N Valid 521

Missing 0

Mean 29,67

Median 30,00

Std. Deviation 3,670

Percentiles 25 28,00

50 30,00

75 32,00

The result of socio-demographic' relation

(gender, age, and GPA) with the level of self-

efficacy is shown in table 3.

The moral reasoning was assessed by a twenty-

item Likert scale. The scale was specifically

developed for this study on the basis of ethical

questionnaire measures developed by Don Forsyth

(Forsyth, O’Boyle and McDaniel, 2008). We,

furthermore, classified the twenty statements into

four attributions theory as suggested by Sykes and

Matza (Stephens, 2007; Sykes and Matza, 1957).

The statements of moral reasoning were acceptable

at 0,86 Cronbach's alpha (three questions were not

valid, we did not include them for further analysis).

Table 3: Frequency statistic on self-efficacy’s quartile (N=521)

Category Low Medium High Very High

Percentile <25% 25-49% 50-74% >75%

N N N N

Gender Man 73 69 77 70

Woman 55 51 52 74

Age 18-20 111 108 115 126

21-23 17 12 14 18

GPA <2.00 2 1 0 2

2.01-2.5 9 9 4 9

2.51-3.00 30 30 27 33

3.01-3.50 55 52 61 66

>3.51 32 28 37 34

Is Self-efficacy Related to Students’ Moral Reasoning?: A Research on Students’ Absentee Behavior

399

3.3 Hypotheses

In this study, the first hypothesis we propose, i.e.:

H1: Act of trusting one self’s presence is morally a

wrong behavior for students.

The next hypothesis will examine GPA’ students

related to their level of self-efficacy. For this, we

hypothesize:

H2: In general, the higher the students’ self-

efficacy, the higher their GPA.

Based on first two-hypotheses above, concerning

moral reasoning and their belief in their moral

standard, we hypothesize:

H3: Students with higher self-efficacy are more

likely to do morally right actions.

4 RESULTS

Each table in this section was measured by

Kendall’s Tau-B (because of non-normality

distribution of the responses, use of non-parametric

statistic was desirable).

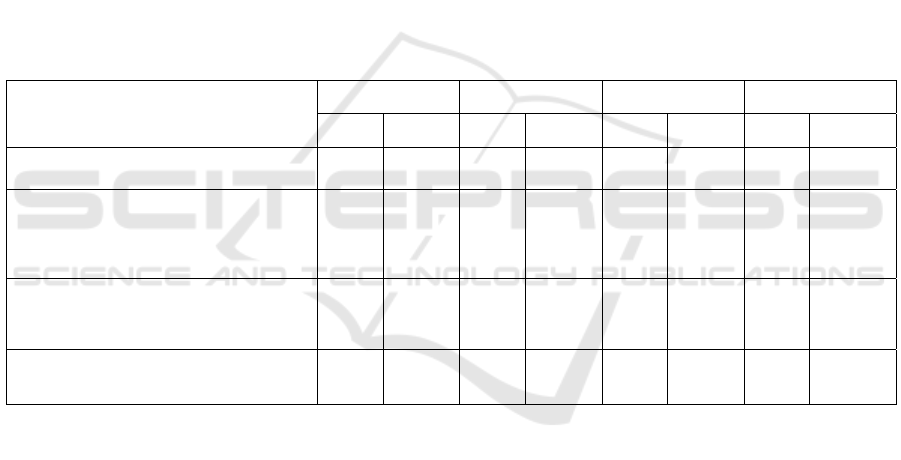

Table 4 summarizes the responses to the four

chosen statements related to moral principles in

trusting one' presence. The mean result related to

their moral principles as shown by the first statement

indicated that the higher students' self-efficacy the

more, they understand moral behavior. Significance'

result of 2-tailed probability (the second and the

third statements) in students with a low, medium,

and high self-efficacy showed that the null

hypothesis was accepted because there was no

relationship between the belief in moral principles

and their perception of the absentee behavior.

Responses to the statements that absentee

behavior is just an academic agreement and has a

smaller impact than getting low scores in

exam/assignment were statistically not significant.

Meanwhile, the belief in moral principles and the

guilty in all level of students' self-efficacy showed a

negative sign. In this case, a negative sign indicated

that students felt guilty when they did an action

which was morally wrong. A correlation of first and

fourth statement, however, was statistically

significant only at students with very high self-

efficacy. It might be that they maintain their belief in

moral principles by feeling guilty when trusting their

presence.

Table 5 displays the moral reasoning’s mean for

each level of self-efficacy were 56,66 (low), 55,82

(medium), 58,35 (high), and 55,93 (very high). The

mean of all students’ moral reasoning was 56.68.

This result indicated that students with high self-

efficacy had an average score above the overall

average of students’ moral reasoning which was

followed in the second order by students with low

self-efficacy. The result also showed that the highest

score of moral reasoning’ scale (84) was in the

student with low self-efficacy. Meanwhile, the

highest GPA’ mean was in students with high self-

efficacy. The lowest GPA’ mean was in students

with medium self-efficacy. The interesting result

was that students with lowest GPA’ mean are more

Table 4: Students' perception of absentee behavior and their belief in moral principles

Low Medium High Very High

Mean 2-tailed Mean 2-tailed Mean 2-tailed Mean 2-tailed

I believe that my moral principles are

truly good and right

4.01 1 4.15 1 4.29 1 4.43 1

In general, I believe that absentee

behavior is a matter of the

rules/academic agreements, not the

issue of moral principles

2.47 0.377 2.56 0.941 2.74 0.877 2.54 0.808

I believe that an absentee behavior only

has a smaller impact than getting a low

score on the exam/assignment

2.63 0.079 2.50 0.979 2.61 0.422 2.56 0.488

I do not feel guilty when I did an

absentee behavior

1.93 - 0.854 1.90 - 0.092 2.05 - 0.081 1.83 - 0.035*

Note: * negative sign shows an opposite relationship (p-value < 0.05)

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

400

likely to make reasoning on the moral decisions.

Their correlation is statistically significant at p-value

<0.05.

Table 6 shows the correlation between all

statements on moral reasoning and each level of

self-efficacy. There were three statements which had

a significant correlation to students' self-efficacy.

The students' responses to ‘I believe that my moral

principles are truly good and right’ and ‘I am able to

convince my friends to tolerate my wrong actions’

were statistically significant in the students with

very high self-efficacy. This result also showed that

the mean for students' moral reasoning was more

likely to increase from low self-efficacy to very high

self-efficacy. Responses to ‘I will not tell the truth if

the lecturer found that my friend trusted his/her

presence through me' was statistically significant in

students with low self-efficacy. The negative sign

for the probability indicated that the higher self-

efficacy the more they will tell the truth about an

existing absentee behavior in the class.

5 DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicated that in doing the

absentee deed there is a very strong relationship

between students' moral principles and their level of

self-efficacy. This result, unfortunately, showed the

inconsistency in the students' behavior regarding

moral principles and their self-efficacy. It might be

that this inconsistency was related to the

neutralization efforts since they encountered the

uncertainty of outcomes (Rettinger, 2007).

Table 5: Socio-demographic variables, moral reasoning, and level of self-efficacy

Category Low Medium High Very High

Percentile <25% 25-49% 50-74% >75%

Students' Moral

Reasoning

minimum scores 35 35 35 35

maximum scores 84 79 83 81

56.66 55.82 58.35 55.93

GPA Mean

2.83 2.81 3.02 2.84

2-tailed* 0.433 0.021** 0.747 0.833

Gender

Man 73 69 77 70

woman 55 51 52 74

N 128 120 129 144

Note: * a correlation between GPA and moral reasoning

** p-value < 0.05

Table 6: A correlation between significant self-report statistically on absentee behavior and level of self-efficacy

Category Low Medium High Very High

<25% 25-49% 50-74% >75%

I believe that my moral principles are truly

good and right

p-value. (2-tailed) -0,295 0,182 0,810 0,000**

mean 4.01 4.15 4.29 4.43

I am able to convince my friends to tolerate my

wrong actions

p-value. (2-tailed) -0,659 -0,270 0,853 0,020*

mean 3.01 3.27 3.40 3.44

I will not tell the truth if the lecturer found that

my friend trusted his/her presence through me

p-value. (2-tailed) -0,003** -0,267 0,556 -0,193

mean 2.63 2.31 2.64 2.24

Note: * p-value < 0.05

** p-value < 0.01

Is Self-efficacy Related to Students’ Moral Reasoning?: A Research on Students’ Absentee Behavior

401

5.1 Denial of Responsibility

Following Murdock and Stephens (Stephens, 2007),

students might know that absentee behavior is

morally wrong but they feel no guilt and personally

are not responsible for behaving in a manner

consistent with their moral judgment. Our finding

showed that students with very high self-efficacy

were able to convince their friends regarding their

deeds which were morally wrong action. This ability

to convince appears along with the level of self-

efficacy where it was indicated by the increasing

mean of students’ moral reasoning.

Moral engagement in making decisions under

risky circumstances seemed to lose moral weight.

The process was termed as externalizing

responsibility to avoid the self-blame and at the

same time to justify their deviant behavior. Our

finding, however, also showed that students with

very high self-efficacy were more likely to feel

guilty of doing absentee than students with low,

medium and high self-efficacy. This result suggested

that the null hypothesis of H1 was accepted.

5.2 Appeal to Higher Priority

As indicated by Sykes and Matza (Sykes and Matza,

1957), students did not necessarily repudiate a

normative system. Rather, they felt that they are

trapped in a dilemma that must be resolved,

unfortunately, by violating the regulations. The most

important point is that the students' deviant behavior

might occur not because the norms are rejected, but

other norms held to be a more pressing priority.

Moral decisions they made on the basis of

conflicting values was often subordinated under the

academic goals. This moral dilemma might relate to

the duty for doing an action that is morally good

despite the not illegal action, mala prohibita, but was

only imposed on the students personally. The

personal goals to become a qualified student were

only inflicted on each the students. As Thorkildsen

et all stated that communal value necessarily offers

helpful practices for encouraging students to resist

the temptation (academic dishonesty) (Thorkildsen,

Golant and Richesin, 2007). In this case, we found

the inconsistency among students regarding their

moral manifestation in certain situations. Yanif et all

stated this dilemma as sacrificing moral principles

(Yaniv, Siniver, and Tobol, 2017)

Opportunities to be students with the best

academic scores enhanced the perceptions that one

has a greater chance and justification for absentee

behavior (Patall and Leach, 2015). The priority in

achieving the academic goals more or less explains

why only students with medium self-efficacy have

statistically a significant probability. The given

result describes what Davis stated as an effort to

choose between a wrong and another wrong (Davis,

2007). This GPA’ variable, however, is not the main

predictor for this attribution. There might be other

predictors which were not entered into the analyses.

The null hypothesis of H2 was accepted that the

higher students’ self-efficacy did not correlate with

the higher students’ GPA.

5.3 Denial of the Crime – The Victim

It was very hard for the students to admit that the

absentee deed was more related to moral behavior

than an illegal action. It might occur since they

defined that their action would not harm the others,

despite in fact their action was contrary to the

regulations. We precisely observed that students

could make a distinction in evaluating the

wrongfulness of their behavior. For the students

with very high self-efficacy, they could turn on a

question of interpretation on their deviant behavior

into whether or not anyone has been hurt by his

actions. In this sense, peers behavior could facilitate

academic dishonesty (Farnese et al., 2011b).

For this kind of reasoning, we suggest that the

moral awareness of students was weakened by

external circumstances which they saw more

important than keeping their moral standard. At the

same time, when caught doing the action, students

pretended to be a victim of what they did earlier.

This was, of course, a strategy to rationalize or even

to externalize moral indignation of the other

(teacher, college) to something abstract. As stated by

Sykes and Matza, internalized norms and

anticipations of the reactions of others must

somehow be activated, if they are to serve as guides

for behavior. It is possible that a diminished

awareness of the victim plays an important part in

determining whether or not this process is set in

motion (Sykes and Matza, 1957). This was made

clear by the results that the students with high self-

efficacy were more likely able to neutralize their

moral standard to be accepted by the others

(classmate, lecturer). Thus, the null hypothesis of H3

was accepted that of the higher self-efficacy did not

correlate with morally good behavior in certain

situations.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

402

6 CONCLUSION

The students' self-efficacy in this study

demonstrated an understanding of how they held the

moral belief in attaining personal academic goals. In

circumstances that demand moral decisions the

higher self-efficacy, the more students are capable of

neutralizing their moral principles to justify or to

make sense of his or her world particularly events

that are negative, unexpected, or not normative.

Students’ GPA indicated that this factor could be a

predictor for increasing the significant probability

into students’ self-efficacy towards moral reasoning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank LPPM Sepuluh Nopember Institute of

Technology for funding our research. The views

conveyed in this publication do not necessarily

represent the views of the supporting institution.

REFERENCES

Anderman, E.M. and Midgley, C., 2004. Changes in

self-reported academic cheating across the

transition from middle school to high school.

Contemporary Educational Psychology, [online]

29(4), pp.499–517. Available at:

<http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S036

1476X04000232>.

Azizli, N., Atkinson, B.E., Baughman, H.M. and

Giammarco, E.A., 2015. Relationships between

general self-efficacy, planning for the future, and

life satisfaction. Personality and Individual

Differences, 82, pp.58–60.

Bandura, A., 1978. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying

theory of behavioral change. Advances in

Behaviour Research and Therapy, [online] 1(4),

pp.139–161. Available at:

<https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/p

ii/0146640278900024> [Accessed 12 Jul. 2018].

Bandura, A., 1999. Moral Disengagement in the

Perpetration of Inhumanities. Personality and

Social Psychology Review, [online] 3(3), pp.193–

209. Available at:

<http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1207/s1532

7957pspr0303_3> [Accessed 5 Jul. 2018].

Bandura, A., 2002. Selective moral disengagement

in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of

Moral Education, [online] 31(2), pp.101–119.

Available at:

<http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0

305724022014322> [Accessed 5 Jul. 2018].

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G.V. and

Pastorelli, C., 1996. Mechanisms of moral

disengagement in the exercise of moral agency.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

[online] 71(2), pp.364–374. Available at:

<http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/002

2-3514.71.2.364> [Accessed 5 Jul. 2018].

Bandura, A., Caprara, G.V., Barbaranelli, C.,

Pastorelli, C., and Regalia, C., 2001.

Sociocognitive self-regulatory mechanisms

governing transgressive behavior. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, [online]

80(1), pp.125–135. Available at:

<http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/002

2-3514.80.1.125> [Accessed 5 Jul. 2018].

Cartwright, E. and Menezes, M.L.C., 2014. Cheating

to win: Dishonesty and the intensity of

competition. Economics Letters, [online] 122(1),

pp.55–58. Available at:

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.10.016

>.

Chen, G., Gully, S.M. and Eden, D., 2001.

Validation of a New General Self-Efficacy Scale.

Organizational Research Methods, [online] 4(1),

pp.62–83. Available at:

<http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10944

2810141004>.

Davis, N.A., 2007. Moral Dilemmas. In: A

Companion to Applied Ethics. [online] Oxford,

UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp.487–497.

Available at:

<http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/9780470996621.c

h36>.

Farnese, M.L., Tramontano, C., Fida, R. and

Paciello, M., 2011a. Cheating Behaviors in

Academic Context: Does Academic Moral

Disengagement Matter? Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences, [online] 29, pp.356–365.

Available at:

<https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/p

ii/S187704281102711X> [Accessed 5 Jul. 2018].

Farnese, M.L., Tramontano, C., Fida, R. and

Paciello, M., 2011b. Cheating Behaviors in

Academic Context: Does Academic Moral

Disengagement Matter? Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences, [online] 29, pp.356–365.

Available at:

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.250>

.

Forsyth, D.R., O’Boyle, E.H. and McDaniel, M.A.,

2008. East Meets West: A Meta-Analytic

Investigation of Cultural Variations in Idealism

and Relativism. Journal of Business Ethics,

Is Self-efficacy Related to Students’ Moral Reasoning?: A Research on Students’ Absentee Behavior

403

[online] 83(4), pp.813–833. Available at:

<http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10551-008-

9667-6>.

Hakimi, S., Hejazi, E. and Lavasani, M.G., 2011.

The relationships between personality traits and

students’ academic achievement. Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, pp.836–845.

Iorga, M., Ciuhodaru, T. and Romedea, S.-N., 2013.

Ethic and Unethic. Students and the Unethical

Behavior During Academic Years. In: Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences. [online]

Elsevier, pp.54–58. Available at:

<https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/p

ii/S1877042813032540> [Accessed 17 Jan.

2018].

LaDuke, R.D., 2013. Academic Dishonesty Today,

Unethical Practices Tomorrow? Journal of

Professional Nursing, [online] 29(6), pp.402–

406. Available at:

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.10.00

9>.

Lawson, R.A., 2004. Is Classroom Cheating Related

to Business Students’ Propensity to Cheat in the

‘Real World’? Journal of Business Ethics,

[online] 49(2), pp.189–199. Available at:

<http://link.springer.com/10.1023/B:BUSI.00000

15784.34148.cb>.

Murdock, Tamera B. and Murdock, E.M., 2006.

Motivational Perspectives on Student

Cheating:Toward an Integrated Model of

Academic Dishonesty. Educational Psychologist,

41(3), pp.129–145.

Murdock, T.B. and Stephens, J.M., 2007. Is

Cheating Wrong? Students’ Reasoning about

Academic Dishonesty. In: E.M. Anderman and

T.B. Murdock, eds., Psychology of Academic

Cheating. [online] Burlington: Elsevier, pp.229–

251. Available at:

<https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/p

ii/B9780123725417500140>.

Palmer, E.J., 2005. The relationship between moral

reasoning and aggression, and the implications

for practice. Psychology, Crime & Law, [online]

11(4), pp.353–361. Available at:

<http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1

0683160500255190>.

Patall, E.A. and Leach, J.K., 2015. The role of

choice provision in academic dishonesty.

Contemporary Educational Psychology, [online]

42, pp.97–110. Available at:

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.06.0

04>.

Rettinger, D.A., 2007. Applying Decision Theory to

Academic Integrity Decisions. In: Psychology of

Academic Cheating. [online] Academic Press,

pp.141–167. Available at:

<https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/p

ii/B9780123725417500115> [Accessed 19 Jul.

2018].

Stajkovic, A.D., Bandura, A., Locke, E.A., Lee, D.

and Sergent, K., 2018. Personality and Individual

Di ff erences Test of three conceptual models of

in fl uence of the big fi ve personality traits and

self-e ffi cacy on academic performance : A

meta-analytic path-analysis. Personality and

Individual Differences, [online] 120(August

2017), pp.238–245. Available at:

<http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.014>.

Stephens, J.M., 2007. Is Cheating Wrong? Students’

Reasoning about Academic Dishonesty.

Psychology of Academic Cheating, [online]

pp.229–251. Available at:

<https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/p

ii/B9780123725417500140> [Accessed 5 Jul.

2018].

Sykes, G.M. and Matza, D., 1957. Techniques of

Neutralization: A Theory of Delinquency.

American Sociological Review, [online] 22(6),

p.664. Available at:

<https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/podzim2016/BSS166

/um/Sykes__Matza_Techniques_of_Neutralizati

on.pdf>.

Thorkildsen, T.A., Golant, C.J. and Richesin, L.D.,

2007. Reaping What We Sow. In:

Psychology of

Academic Cheating. [online] Elsevier, pp.171–

202. Available at:

<http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B978

0123725417500127>.

Turiel, E., 2015. Moral Reasoning in Psychology.

In: International Encyclopedia of the Social &

Behavioral Sciences. [online] Elsevier, pp.803–

805. Available at:

<https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/p

ii/B9780080970868250204> [Accessed 12 Jul.

2018].

Yaniv, G., Siniver, E. and Tobol, Y., 2017. Do

higher achievers cheat less? An experiment of

self-revealing individual cheating. Journal of

Behavioral and Experimental Economics,

[online] 68, pp.91–96. Available at:

<http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S221

4804317300411>.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

404

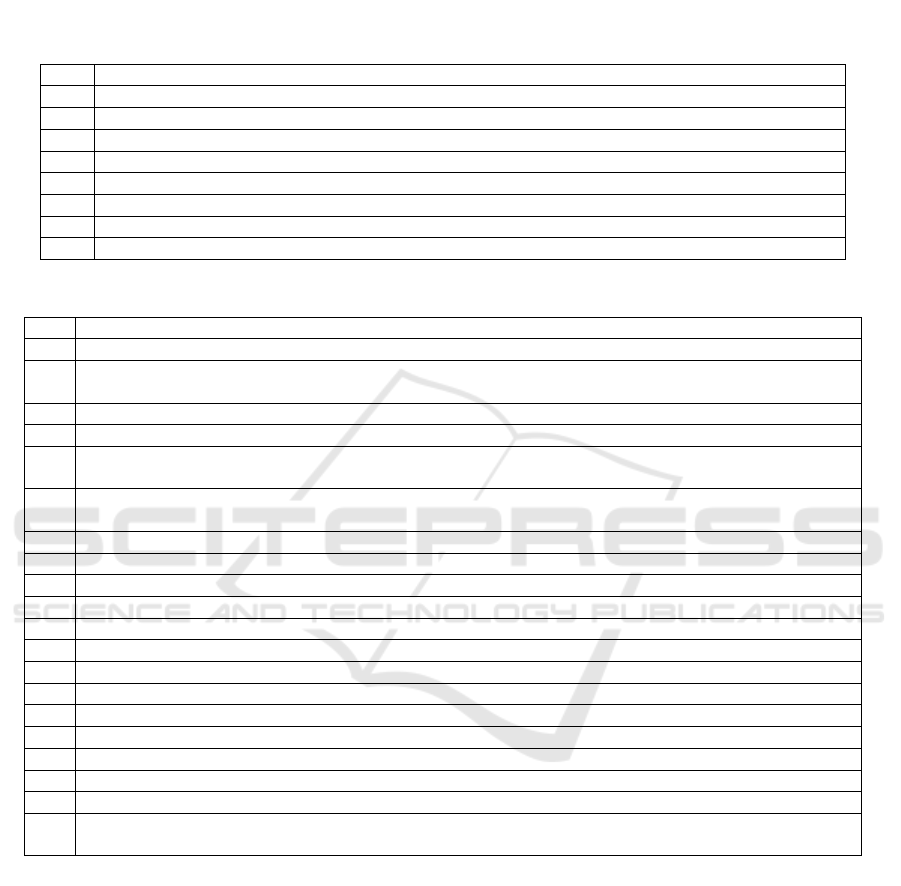

APPENDIX

Appendix 1: Self-Efficacy scale

No Item

1 Sa

y

a mam

p

u menca

p

ai seba

g

ian besar tu

j

uan

y

an

g

sudah sa

y

a teta

p

kan

2 Ketika saya menghadapi tugas sulit maka saya yakin akan dapat menyelesaikannya

3 Secara umum, saya akan bisa mendapat hasil baik yang penting bagi diri saya

4 Saya percaya bahwa saya berhasil dengan maksimal untuk usaha yang saya tetapkan

5 Sa

y

a akan mam

p

u men

y

elesaikan ban

y

ak tantan

g

an den

g

an bai

k

6 Sa

y

a

y

akin bahwa sa

y

a bisa tam

p

il efektif dalam berba

g

i hal

7 Dibandin

g

kan den

g

an oran

g

lain, sa

y

a bisa melakukan tu

g

as den

g

an san

g

at baik

8 Bahkan ketika menghadapi persoalan yang sulit, saya dapat menyelesaikannya dengan bai

k

Appendix 2: Moral Reasoning scale.

No Item

1 Sa

y

a

y

akin bahwa

p

rinsi

p

moral

y

an

g

sa

y

a anut adalah sun

gg

uh-sun

gg

uh baik dan bena

r

2 Secara umum, saya meyakini bahwa tindakan titip absen adalah persoalan Aturan/Kesepakatan Akademis

b

ukan

p

ersoalan

p

rinsi

p

Moral

3 Sa

y

a me

y

akini bahwa teman satu

j

urusan da

p

at diandalkan untuk melakukan titi

p

absen

4 Sa

y

a

p

erca

y

a bahwa teman sa

y

a sun

gg

uh-sun

gg

uh memahami men

g

a

p

a sa

y

a harus melakukan titi

p

absen

5 Di tengah kesibukan dan banyak tuntutan tugas, saya mampu mengatur waktu tanpa mengorbankan

kehadiran di kelas selama

p

erkuliahan

6 Saya percaya bahwa tindakan titip absen hanya berakibat lebih kecil daripada mendapat nilai rendah

dalam ujian/tugas.

7 Saya mampu melaksanakan prinsip moral yang saya anut dengan setia

8 Sa

y

a

p

erca

y

a bahwa sa

y

a mam

p

u mematuhi setia

p

p

eraturan den

g

an baik dan bena

r

9 Sa

y

a mam

p

u me

y

akinkan teman sa

y

a untuk mentoleransi tindakan sa

y

a

y

an

g

salah

10 Sa

y

a berani melakukan titi

p

absen karena

p

roses

p

erkuliahan

y

an

g

sa

y

a ikuti tidak be

g

itu menarik.

11 Saya tidak merasa bersalah ketika melakukan titip absen

12 Menurut saya, tindakan titip absen tidak berdampak pada sanksi akademis yang fatal

13 Jika ada teman sa

y

a

y

an

g

melakukan titi

p

absen, sa

y

a ber

p

enda

p

at itu adalah tindakan

y

an

g

lumrah/wa

j

a

r

14 Sa

y

a ber

p

ikir bahwa titi

p

absen adalah tindakan

y

an

g

tidak terlalu serius

15 Sa

y

a men

g

etahui den

g

an san

g

at baik kebi

j

akan tentan

g

aturan titi

p

absen

16 Teman-teman saya cenderung membiarkan jika saya melakukan titip absen

17 Demi solidaritas, saya bersedia melakukan titip absen untuk teman saya

18 Saya akan memberikan alasan yang masuk akal jika ketahuan titip absen

19 Menurut sa

y

a, sa

y

a melakukan titi

p

absen karena ban

y

akn

y

a tu

g

as akademis.

20 Saya tidak akan mengatakan yang sebenarnya jika dosen mengetahui teman saya melakukan titip absen

melalui saya

Is Self-efficacy Related to Students’ Moral Reasoning?: A Research on Students’ Absentee Behavior

405