A Preliminary Study of Screen-media, Empathizing, and Systemizing

in Children

Ni Putu Adelia Kesumaningsari

1

, Meidy Christianty Soesanto

1

, Nova Retalista

1

, Xuan Hongzhou

2

,

and Wang Yiming

3

1

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Surabaya, Indonesia

2

Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Zhejiang University, China

3

Henan Institute of Technology and Science, China

Keywords: Screen-based media use, Empathizing-Systemizing, Autistic Traits.

Abstract: This study aims to examine the relationship between screen time and empathizing-systemizing cognitive

styles. To date, the present study involved 197 parents of elementary school children in Indonesia, 7-11

years old. Parents completed several questionnaires addressing children’s screen-time, screen activities, and

Empathizing-Systemizing Quotients (EQ-SQ Child). The results showed that children spent more than 4

hours on average per day with media use, infringes the rules by the American Pediatric Association about

healthy duration screen activities for children. The research also found gender preferences toward screen-

activities. Boys were reported engaged more with gaming and watching activities than girls. Regarding

Empathizing-Systemizing cognitive styles, the result indicates a non-significant relationship between total

screen time and Empathizing-Systemizing (E-S). However, a specific relation was found between the type

of screen activities and the E-S. Watching activities (TV, videos, and movies), playing video games, and

doing homework showed a negative relation with Empathizing. On the other side, watching activities is also

related negatively with Systemizing. Moreover, Gaming was found to be correlated with the D-Score. The

result highlights the clinical importance of examining the role of media on children development as the

finding has suggested the role of media to the E-S cognitive styles, therefore indirectly explained the effects

of screen-based media on the development of autism among children.

1 INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of autism that escalated over time

prompts the investigation of possible environmental

factors in autism. Current research tries to figure out

other confounding environmental factors in autism

(Mazurek, et al., 2012). Environmental risk factors

may contribute to the development of autism,

perhaps via a complex interaction between genes

and environment (Newschaffer, et al., 2007). One

environmental factor that has been questioned to the

development of autism is the usage of screen-based

media.

The question whether screen usage contributes to

the development of autism keeps arising, since a

research by Waldman, Nicholson and Adilov (2006)

appears which reported that the introduction of cable

TV in the 80's was followed by a 17% increase in

the number of cases of autism, indicating that the

question about this issue is not something new.

Media has been linked to the autism since many

researches showed that autistic children were highly

fascinated with the screen technology. People with

autism are more likely to spend the majority of their

free time with particular electronic media (Orsmond

and Kuo, 2011). In another research, autistic

individuals are reported having vigorous choices for

screen-based media (Mazurek and Engelhardt,

2013), prefer more on non-social media use, and

show lower rates of social media use compared to

other disability groups such as speech/language

impairment, learning disabilities, and intellectual

disabilities. The non-social media refers to media

that not stimulate social interaction, for example,

video games (Mazurek, et al., 2012). Research in

autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) children also

indicated that ASD children participate in screen-

based activities, i.e. watching television and playing

video games more often than any leisure activities,

both on weekend and weekdays (Shane and Albert,

2008). The findings seem to suggest that there is a

368

Kesumaningsari, N., Soesanto, M., Retalista, N., Hongzhou, X. and Yiming, W.

A Preliminary Study of Screen-media, Empathizing, and Systemizing in Children.

DOI: 10.5220/0008589603680375

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS 2018) - Improving Mental Health and Harmony in

Global Community, pages 368-375

ISBN: 978-989-758-435-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

unique attraction of screen-based media in the

autistic individual.

In typical children, the intensive use of screen-

technologies seems to exhibit the autistic-like

characteristic. Engagement in restrictive interest,

lack of social interaction, and repetitive behaviour is

a diagnostic feature of ASD (APA, 1994). The

intense media influence relates to impaired language

acquisition and social behaviour (Tanimura, Okuma

and Kyoshima, 2007). On a separate research

finding, the screen-media decreasing the children

ability to infers the feeling of others. Sixth-grade

children in elementary school who receive screen

diet within the five days has shown better ability to

recognise emotion compared to children who

routinely engage with screen technologies (cited in

Dunckley, 2015). Research also shows that specific

screen-activities, i.e. gaming increases the level of

anxiety and social phobia which prompt the deficit

of making the social connection among people

(Gentile, et al., 2011).

Some investigations in children reflect how the

screen-activities affecting the systemizing ability in

children, leading to the development of restrictive

interest in children. Repeated exposure to cinematic

codes presented on film, such as zoom technique,

lead to higher scores on search tasks which require

children to find detail in the interlaced display

(Salomon, 1979; Schmidt and Vandewater, 2008).

Other experiments revealed that media use (gaming

and television) increases the visual-spatial attention

and elevates the ability to track more items in a

group of dynamic distractor items, locate a brief

target more quickly, and process on-going

information more efficiently (Green and Bavelier,

2003; Schmidt and Vandewater, 2008).

Therefore, it can be argued that the use of screen-

based media among children contributes to the

development of autistic-like characteristic, or, might

escalate the autistic traits. Despite numbers of

assumption growing about the exciting link between

autism and media, research has tried to reveal the

indications that exposure to screen-time is possibly

related to autism. A retrospective study in infants

investigated the role of television in autism. It

demonstrates that children with autism started

watching television six months earlier, at six months

of age, compared to the children without autism.

Afterwards, this study’s results indicate that earlier

onset and higher television viewing frequency might

be a precursor of autism (Chonchaiya, Nuntnarumit

and Pruksananonda, 2011).

A way to understand the autistic-like

characteristic would better explained by the social

brain of autism. The new theory of social cognition

in autism suggested that that autistic individual

possesses masculinised cognitive traits that are

elucidating both of those social and non-social

features, namely Empathizing-Systemizing. Further,

this theory also categorized the typical cognitive

abilities of human into five types of brain, i.e. types

as type S ( S>E, more common in males), type E (

E>S, more common in females), type B (E=S),

Extreme S (S>>E, common in autism), and Extreme

E (E>>S), that measured by the D-Score, the

average of the discrepancies between systemizing

and empathizing (Baron-Cohen, Knickmeyer and

Belmonte, 2005).

Therefore, the E-S theory by Baron-Cohen

(2009), has suggested ASD cognitive traits

specifically imposed as Extreme Male Brain

conditions, characterised by weak empathizing skills

and high systemizing skills. In daily life, ASD

individual can be observed to have good analytical

skills indicated two majors' islets abilities, but low

social skills. From the cognitive perspective,

Empathizing (E) refers to the ability to identify and

infer others’ mental state, while Systemizing (S)

reflects the ability to analysed or construct a system

by noting regularities and rules (Baron-Cohen, 2009;

Baron-Cohen and Belmonte, 2005). The Empathy

Quotient (EQ) and the Systemizing Quotient (SQ)

were constructed as instruments to test the E–S

theory (Baron-Cohen, et al., 2003; Baron-Cohen and

Wheelwright, 2004).

Previous research by the first authors about

screen-based media use and extreme male brain on

4-6 and 10-11 years children in Indonesia has been

trying to examine the effects of media on both of E-

S ability and autistic traits (Kesumaningsari,

Stauder, and Donkers, 2017). However, the finding

seems to be vague and inconsistent. The authors

argue that this might be caused by including 4-6

years children as a subject who makes parents hard

to estimate the usage of screen-media regarding

social media use and also doing homework.

Therefore, the current study aims to focus only on

finding the relation of screen-based media and E-S

cognitive styles in 7-11 years.

The school-aged children were chosen as the

subject in this current study is due to several

reasons. First, according to the developmental

stages, the school ages children already develop a

better skill to infer other emotion compared to

preschool children. As a consequence, it can be

assured that the level of empathizing skills on

children is not due to immaturities. Second, the

school ages children have more variation in screen

A Preliminary Study of Screen-media, Empathizing, and Systemizing in Children

369

type activity, especially regarding the social media

use which might be affected the social skills, highly

related with empathizing skills.

To sum up, the current research will try to

examine the relation of the use of screen-media on

7-11 years children in Indonesia with Empathizing-

Systemizing, which further can be used to explain

whether media have a relation on the development

of autism which will be reflected on the D-Score.

Moreover, today, as the screen technology

proliferates and fills with interactive screen media

use (any activity with a touchscreen smartphone,

console, moving sensor, or keyboard) (Dunckley,

2015), which more or less giving a developmental

effect in children, highlighting the importance of the

research on this issue.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

This study was a descriptive and correlational study.

There were 197 parents with school-aged children

between 7-11 years old in Indonesia had participated

in this study reporting the condition of their children

related to variables measured. Therefore, the sample

consisted of 197 school-aged children in Indonesia,

50.3% of boys (N=99) and 49.7% of girls (N = 98).

The participant had an average age of 9 from age

rage 7 – 11 years (SD = 1.588).

The inclusion criteria of the participants were

having child engages with screen-based media

technology and has never been diagnosed with any

disorder. The data collection was performed upon an

online link contained the measurement scales which

computed in Qualtrics online platform. Before

completing the questionnaires, participants first

completed informed consent pages.

2.2 Measures

Screen based media use (i.e. screen-time and type of

screen activities) and empathizing and systemizing

quotient were explored in this study. The

measurement scales utilized in this study were

translated into Indonesian Language by the author

on April 2017 according to the cross-cultural

adaptation guidelines of self-reports (Beaton, et al.,

2000). The scales back-translated by an independent

translator and reviewed by professionals or expert

committee as a final evaluation to confirm there was

no substantial loss when comparing the original and

the translation scales.

2.2.1 Screen - Based Media Use

The media use survey examines the average amount

of time children spent in screen-based media use.

The survey is completed by the parents. The survey

modifies the survey of Mazurek and Wenstrup

(2013), focusing only on screen-based media

activities during both weekday and weekend such as:

(1) Watching television, videos, and movies; (2)

Playing video games; (3) Engaging in social media;

(4) Internet browsing (5) Working on homework.

The researcher also informed the parents that the

type of media utilized was not limited to any screen-

based technologies, but also included handheld

devices, e.g. smartphones and tablets, which might

be handled by the children. Parents should give their

responses according to a 6-point scale: (0) none at

all; (1) less than 0.5 hours; (2) more than 0.5–1 hour;

(3) more than 1–2.5 hours; (4) more than 2.5–4

hours; (5) more than 4 hours. Consistent with

previous methods used by Orsmond and Kuo (2011)

and Mazurek and Wenstrup (2013), an average daily

use variable was created for each activity by

multiplying the weekday score by 5, multiplying the

weekend score by 2, add the both of the value, and

then dividing the sum by 7.

2.2.2 Empathizing-Systemizing

The E-S Quotient-Child is a questionnaire with 55

items consisting of Empathy Quotient (EQ-C)

subscales and Systemizing Quotient (SQ-C)

subscales, developed to detect trends in gender-

typical behavior of children 4-11 years old. The EQ

and SQ Child consist of a list of statements about

real-life situations, experiences, and interests in

which empathizing or systemizing skills are

required. The questionnaire has four alternatives for

each question. The parent indicates how strongly

they agree with each statement about their child by

choosing one of these alternatives: ‗definitely agree;

‗slightly agree; ‗slightly disagree; or ‗definitely

disagree (Auyeung, et al., 2009). In this study, the

EQ-C and SQ-C had an acceptable Cronbach’s

alpha, α = .866 and α = .758 respectively.

3 RESULT

Result indicated that children (boys = 99, girls = 98)

in current sample spent more than 4 h per day using

screen-based media (television, smartphone, I-Pad,

computer/laptop, and video games). Explored with t-

test, the result also indicated a typically sex

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

370

dependent screen activities among children. Boys

was reported to spent more time on watching (t =

2,030, p <.000, 95% = .008, .557) and gaming

activities (t = 2.972, p <.000, 95% = .184, .908)

compared with girls, as a statistically difference on

average screen-time was found between boys and

girls on the type of screen activities. However, the

result did not indicate the typically sex related

screen-activities for girls.

With regard to E-S cognitive styles, we found

that on average, children had a high level of

empathizing (M = 27.3, SD = 7.83) based on the EQ

score. We also found that children had a low level of

systemizing (M = 22.3, SD = 6.50). The effects of

sex on E-S cognitive styles was found in

empathizing, which girls shows a significance

difference if compared with boys, where scores of

the girls was higher (t = -2.884, p <.000, 95% = -

5.321, -1.000). However, no significant sex

difference was found with regard to systemizing (p>

.000). Nevertheless, the sex effects on D-Score

remained. Our results show a statistically significant

differences in D-Score where boys suggested to be

higher than girls (t = 3.726, p <.000, 95% = .014, -

.047). In particular, girls have a negative D score,

while boys showed a positive D score.

D-Score describes the brain type which derived

from the average of discrepancies between

systemizing and empathizing. D-Score will express

more masculine cognitive traits (male brain) if the

D-Score is greater or more positive, indicating the

SQ is greater than the EQ. Likewise, the small value

or more negative, suggesting that the EQ is greater

than SQ which less represent masculine cognitive

traits. Therefore, the result suggested that boys

having more masculine cognitive traits than girls.

The difference between boys and girls related to

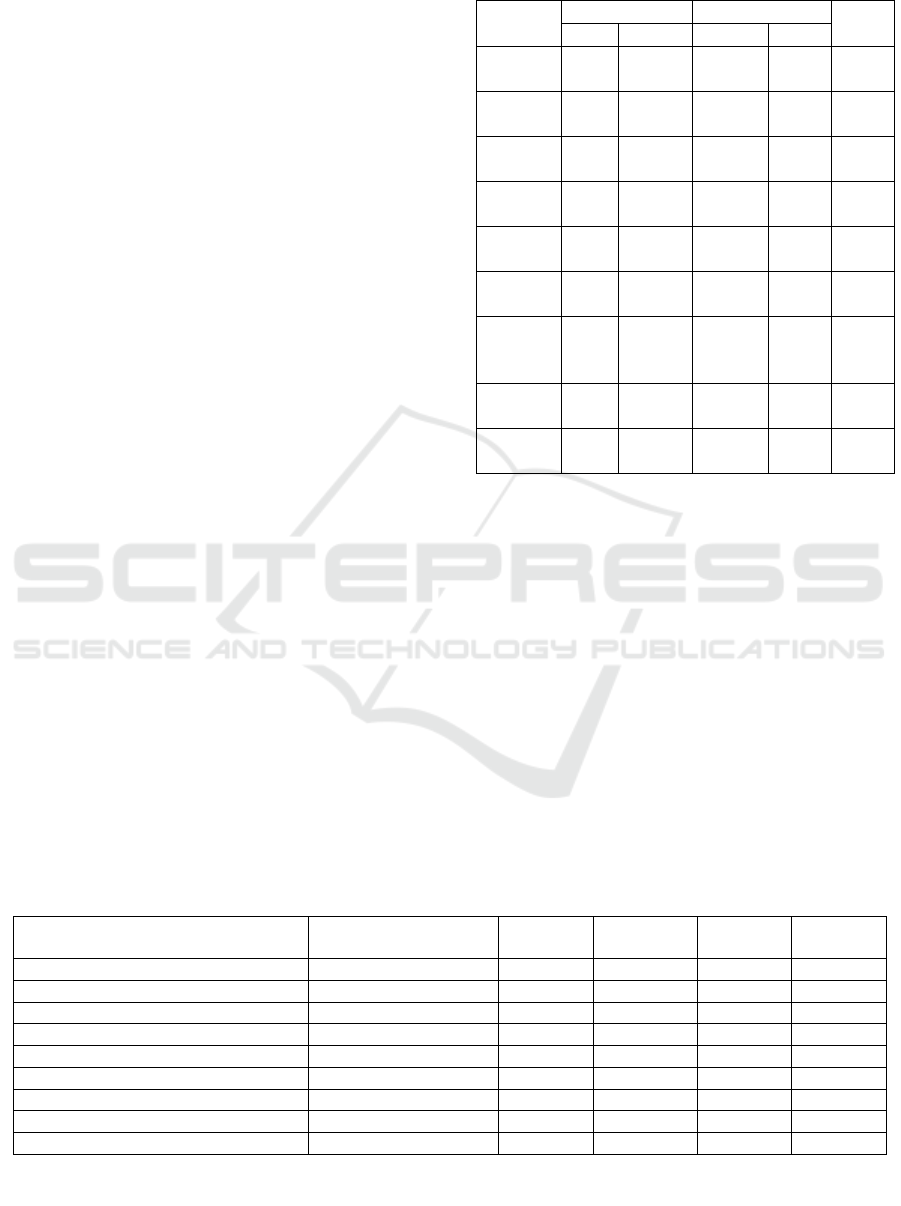

variables measured are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: t-test Results Comparing Boys and Girls on

Screen-Based Media Use, EQ, SQ, and D-Score

Males Females t-test

M SD M SD

Media

Use

8.77 3.146 8.28 3.237 1.095

Watching 2.88 .971 2.59 1.052 2.030

*

Gaming 2.25 1.350 1.70 1.222 2.972

*

Social

Media

.62 1.027 .91 1.184 -

1.803

Internet

Browsing

.92 .998 1.02 1.038 -

0.717

Homewo

rk

2.11 .890 2.06 .848 0.391

EQ 25.7

2

7.253 28.88 8.106 -

2.884

*

SQ 22.3

9

6.453 22.17 6.578 0.237

D-Score 0.01 0.053 -0.01 0.063 3.726

**

Notes: N = 197

‘*’ = p < .05, ‘**’= p < .001

Finally, based on Pearson’s correlation test, we

did not find any significant correlation between the

average time children spent on screen-based media

toward the empathizing, systemizing, even more the

D-Score (p > .05). However, the significant

correlation was found between the average time

children spent in several screen-time activities and

dependent variables measured. The correlation test

found that there was a significantly negative and

small correlation between the average time spent in

watching activities and empathizing in 7-11 years

children (r = -.235, p < .05). This means that high

screen-time in watching activities, was related to

Table 2: Correlations among of Variable Measured

M (SD)

Age

EQ

SQ

D-Score

Media Use 8.53

(

.3.19

)

.338** -.077 -.053 .041

Watchin

g

or Video Streamin

g

2.73

(

1.02

)

-.015 -.235** -.171* .117

Pla

y

in

g

Video Games 1.98

(

1.31

)

.091 -.208** -.073 .179*

Accessing Social Media .77 (1.11) .390** .060 -.024 -.094

Internet Browsing .97 (1.01) .316** .070 .030 -.055

Homewor

k

2.08 (.87) .255** .150 .112 -.072

EQ 27.30

(

7.83

)

.142* - - -

SQ 22.28

(

6.50

)

.082 - - -

D-Score .004

(

.061

)

-.091 - - -

Notes: N = 197

‘*’ = p < .05, ‘**’= p < .001

A Preliminary Study of Screen-media, Empathizing, and Systemizing in Children

371

low empathizing, likewise low watching screen time

was related to high empathizing. Further analysis

showed that there were also significantly negative

correlations between average time devoted in

playing video games and empathizing (r = -.208, p <

.05). Playing video games also shown s significantly

positive correlation with the D-Score (r = .179, p <

.05). Regarding the systemizing, we found that the

time devoted in watching activities was associated

negatively with systemizing, with small correlation

magnitude (r = -.171, p < .05) (see Table 2).

4 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate the

relationship between screen media, empathizing, and

systemizing cognitive styles among 7-11 years

children in Indonesia further to explain the possible

connection between the use of media among

children and the development of autism. On average

spend more than 4 hours to engage with this

technology, which infringes the regular rule by

American Pediatric Association about proper

duration time to use screen-based media. American

Pediatric Association suggested that the appropriate

screen-time consumption is less than 2 hours

(American Academy of Pediatrics, 2011).

The present study did not confirm the expected

findings of the relationship between the average of

time children spent on media with empathizing,

systemizing, or even more the D-Score which

reflected the autistic traits in children. The finding

means that the average children’s screen time during

a week did not contribute to the E-S cognitive styles.

Even though non-significant correlation was found

between variables measured, one of the interesting

findings in this study is that the E-S cognitive styles

correlate with time spent on a specific screen-types

activity.

The current research demonstrates a significant

correlation between watching activities and gaming

with empathy in an inverse relationship, suggesting

an apparent effect of screen-based media devices on

child‘s empathizing level. The correlation indicates

an inverse direction; as a child spends more time on

watching activities or playing video games, his or

her empathizing score decreases, and vice versa.

This result is not surprising because there are a

growing number of studies that showed the negative

contribution of watching and playing video games

activities to empathizing skills in children.

Wilson (2008) has explained that watching, in

this case watching television, will affect a child’s

level of empathy because the children often relate

themselves to the character that they watch.

Therefore, according to this argument, the effect of

watching activities on child development seems

content dependent. In other words, if children are

exposed to repeated negative content, therefore it

might pose risk for children in how they learn share

emotions with others or being empathetic.

Similar to watching activities, the effects of

video games on empathy might occur because of the

harmful content of video games that been played by

the children. A recent experimental study in children

has found that frequently aggressive content gaming

decrease the emotional and cognitive empathy

(Siyez and Baran, 2017), whereas the children will

develop more positive attitude if the children play

pro socially games (Gentile, et al., 2009; Harrington

and O‘Connell, 2017). It would occur because there

is a cognitive transferring process while children

engaged with specific content in screen-based

media. A repeated exposure could produce certain

long-term effects such as changes to cognitive

construct, cognitive-emotional constructs, and

affective traits.

Regarding the S cognitive style, it was expected

that the time devoted on-screen media should

correlate positively with systemizing. The result

suggested that watching activities correlate

negatively with systemizing. The result does not in

line with the direction of relationship that we expect

which should be a positive correlation, as several

experimental studies have found that the use of

screen-based media on children shown positive

effects with the ability of children to analyse system

or detecting details (Subrahmanyam, et al., 2000; Li

and Atkins, 2004; Schmidt and Vandewater, 2008 ).

Albeit the contrary findings, the author argues that

the relation between watching activities and

systemizing is weak because according to the

correlation magnitude. After inspecting the

empirical mean of the systemizing score, it was

found that the systemizing level among children was

generally low if compared with the theoretical mean,

suggesting an explanation why the expected result

did not occur.

Another promising finding was that the relation

between screen media and D-Score (standardized

score on the EQ and SQ, demonstrating strong sex

differences and led to the ‘brain types’). The result

demonstrated that the time spent on playing video

games correlates positively with the D-Score,

suggesting the effects of media i.e. video games on

the development of systemizing cognitive styles (S

brain type) in children. The correlation indicates a

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

372

linear direction; as a child spends more time on

playing video games, his or her D-Score is

increasing, and vice versa. As the D-Score was

calculated using the formula D = (S-standardized –

E-standardized)/2, therefore the more positive the D

Score indicating that the sample has more

systemizing quotient instead of empathizing quotient

score. In short, positive D-Score indicates more S

brain type.

From the evidence currently available, it seems

fair to suggest that the time devoted to watching

television and playing video games related to the

development of autism cognitive styles

characteristic. At one side, its high use of watching

and playing video games was associated with the

low empathizing level. On the other hand, the time

spent on playing video games was associated with

the high systemizing level. As the finding indicates

playing video games is related with the tendency of

greater S brain type or male brain, the current

research suggested that playing video games has a

stronger role in developing masculine cognitive

traits in children, whereas the time devoted on

watching the television takes parts on lowering

empathetic skills.

This result ties well with previous studies about

autism and screen-based media. Mazurek and

Wenstrup (2003) in their study that examined the

nature of television, video game, and social media

use in children (ages 8–18) with autism spectrum

disorders compared to typically developing siblings

has showed that children with ASD spent

approximately 62% of their time watching television

and playing video games, and had higher levels of

problematic video game use if compared with their

typically developed siblings. Moreover, in another

study, Mazurek and Engelhardt (2013) revealed that

this problematic video game was significantly

correlated with inattention and oppositional behavior

in autistic children.

The close link between watching activities and

video games in autism is continuing to the ages, as

the study by Mazurek, et al. (2012) in youth with

ASD has found that majority of youths with ASD

spent most of their free time using non-social media

(television, video games). A similar pattern of

results was also obtained by Orsmond and Kuo

(2011) time diaries research which found that

watching television and using a computer as the

most frequent activities in ASD adolescents’

optional activities. The previous studies seem to

support the current findings in this research about

the role of screen-media to the development of

autism in children that is the time devoted to

watching and playing video games.

To sum up the current research manage to find

the relation between screen-based media and E-S

cognitive style. The current research provides a good

beginning for understanding the relationship

between screen-based media experience and how

does it tie to the cognitive profile of autism.

However, there are several limitations of the current

research to be considered in further research. First,

to measure from the parents observing from their

children seems to be indirect data collecting which

affecting the validity. The measure of frequency use

was based solely on the parental report in a very

general term, which might be subject to errors in

estimation and recall. Second, the small correlation

between variables makes the findings on this study

should be interpreted by caution, since the effects of

media on the development of autism might only take

a small part, notably, however, the relationship is

still statistically meaningful. To sum up, future

experimental and longitudinal research in this area is

needed to test the nature and direction of the

causality between the screen-media use and the

development of autism among children.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The result suggests the role of the time spent on

specific screen activities on the development of E-S

Cognitive Styles, i.e. watching/video streaming and

playing video games. The time spent in

watching/video streaming is related with

empathizing and systemizing in a positive direction,

whereas inverse relationship has found between

playing video games and empathizing. The finding

is also providing the role of screen-based media,

specifically playing video games in the development

of S brain type. The result provides an early

understanding how does the screen-based media

related to autism in children and highlight the

clinical importance of examining video games and

watching activities as factors that should be

concerned in the development of autistic traits in

children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges J.E.A Stauder,

Ph.D, associates Professor from Faculty of

Psychology and Neuroscience, Maastricht

A Preliminary Study of Screen-media, Empathizing, and Systemizing in Children

373

University, Netherlands who supervised the work by

first author about Media use and the Analytical

Brain” Screen-Based Media Use and Behavioural

Preference in Indonesian Children as master theses

in Maastricht University. This current manuscript is

considered as further research expanding the prior

research of first author.

REFERENCES

American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001. Children,

adolescents, and television. Pediatrics, 107(2),

pp.423-426. 10.1542/peds.107.2.423.

American Psychiatric Association (APA), 1994.

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC : American

Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Auyeung, B., Wheelwright, S., Allison, C.,

Atkinson, M., Samarawickrema, N. and Baron-

Cohen, S., 2009. The Children‘s Empathy

Quotient and Systemizing Quotient: Sex

Differences in Typical Development and in

Autism Spectrum Conditions. Journal of Autism

and Developmental Disorders, [e-journal]

39(11), pp.1509. 10.1007/s10803-009-0772-x.

Baron-Cohen, S. and Belmonte, M. K., 2005.

Autism: a window onto the development of the

social and the analytic brain. Annu Rev Neurosci,

[e-journal] 28, pp.109-126.

10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144137.

Baron-Cohen, S. and Wheelwright, S., 2004. The

empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with

Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism,

and normal sex differences. J Autism Dev

Disord, 34(2), pp.163-175.

Baron-Cohen, S., 2009. Autism: the empathizing-

systemizing (E-S) theory. Ann N Y Acad Sci, [e-

journal] 1156, pp.68-80. 10.1111/j.1749-

6632.2009.04467.x.

Baron-Cohen, S., Richler, J., Bisarya, D.,

Gurunathan, N. and Wheelwright, S., 2003. The

systemizing quotient: an investigation of adults

with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning

autism, and normal sex differences. Philos Trans

R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 358(1430), pp.361-374.

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F. and

Ferraz, M. B., 2000. Guidelines for the process

of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report

measures. Spine, [e-journal] 25(24), pp.3186-

3191. 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014.

Chonchaiya, W., Nuntnarumit, P. and

Pruksananonda, C., 2011. Comparison of

television viewing between children with autism

spectrum disorder and controls. Acta Paediatr,

[e-journal] 100(7), pp.1033-1037.

10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02166.x.

Dunckley, V. L., 2015. Reset Your Child's Brain : A

frour week plan to end meltdowns, raise grades,

and boost social skills by reversing the effects of

electronic screen. California: New World

Library.

Gentile, D. A., Anderson, C. A., Yukawa, S., Ihori,

N., Saleem, M., Ming, L. K., Sakamoto, A.,

2009. The Effects of Prosocial Video Games on

Social Psychology Bulletin, [e-journal] 35(6

Prosocial Behaviors: International Evidence from

Correlational, Longitudinal, and Experimental

Studies. Personality and), pp.752-763.

10.1177/0146167209333045.

Gentile, D. A., Choo, H., Liau, A., Sim, T., Li, D.,

Fung, D. and Khoo, A., 2011. Pathological

Video Game Use Among Youths: A Two-Year

Longitudinal Study. Pediatric, [e-journal] 127,

pp.319-329. 10.1542/peds.2010-135.

Green, C. S. and Bavelier, D., 2003. Action video

game modifies visual selective attention. Nature,

[e-journal] 423(6939), pp.534-537.

10.1038/nature01647.

Harrington, B. and O‘Connell, M., 2016. Video

games as virtual teachers: Prosocial video game

use by children and adolescents from different

socioeconomic groups is associated with

increased empathy and prosocial behaviour.

Computers in Human Behavior, [e-journal] 63,

pp.650-658.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.062.

Kesumaningsari, N.P.A, Stauder, J.E.A, & Donkers,

F.C.L., 2017.

“Media use and the Analytical

Brain” Screen-Based Media Use and

Behavioural Preference in Indonesian Children.

M.Sc.. Maastricht University (Unpublished).

Li, X. and Atkins, M. S., 2004. Early Childhood

Computer Experience and Cognitive and Motor

Development. Pediatrics, [e-journal] 113(6),

1715-1722. 10.1542/peds.113.6.1715.

Mazurek, M. O. and Engelhardt, C. R., 2013. Video

game use and problem behaviors in boys with

autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism

Spectrum Disorders, [e-journal] 7(2), pp.316-

324. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.09.008

Mazurek, M. O. and Engelhardt, C. R., 2013. Video

game use and problem behaviors in boys with

autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism

Spectrum Disorders, [e-journal] 7(2), pp.316-

324.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.09.008.

Mazurek, M. O. and Wenstrup, C., 2013. Television,

video game and social media use among children

with ASD and typically developing siblings. J

Autism Dev Disord, [e-journal] 43(6), pp.1258-

1271. 10.1007/s10803-012-1659-9.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

374

Mazurek, M. O., Shattuck, P. T., Wagner, M. and

Cooper, B. P., 2012. Prevalence and correlates of

screen-based media use among youths with

autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord,

[e-journal] 42(8), pp.1757-1767.

10.1007/s10803-011-1413-8.

Newschaffer, C. J., Croen, L. A., Daniels, J.,

Giarelli, E., Grether, J. K., Levy, S. E. and

Windham, G. C., 2007. The epidemiology of

autism spectrum disorders. Annu Rev Public

Health, [e-journal] 28, pp.235-258.

10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007.

Orsmond, G. I. and Kuo, H.-Y., 2011. The daily

lives of adolescents with an autism spectrum

disorder: Discretionary time use and activity

partners. Autism: the international journal of

research and practice, [e-journal] 15(5), pp.579-

599. 10.1177/1362361310386503.

Salomon, G., 1979. Interaction of Media, Cognition,

and Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bas.

Schmidt, M. E. and Vandewater, E. A., 2008. Media

and attention, cognition, and school achievement.

Future Child, 18(1), pp.63-85.

Shane, H. and Albert, P., 2008. Electronic screen

media for persons with autism spectrum

disorders: Results of a survey. Journal of Autism

and Developmental Disorders. 38(8), pp.1499–

1508.

Siyez, D. M. and Baran, B., 2017. Determining

reactive and proactive aggression and empathy

levels of middle school students regarding their

video game preferences. Computers in Human

Behavior, [e-journal] 72, pp.286-295.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.006.

Subrahmanyam, K., Kraut, R. E., Greenfield, P. M.

and Gross, E. F., 2000. The impact of home

computer use on children's activities and

development. The Future Children, [e-journal]

10(2), pp.123-144. 10.2307/1602692.

Tanimura, M., Okuma, K.. and Kyoshima, K., 2007.

Television viewing, reduced parental utterance,

and delayed speech development in infants and

young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, [e-

journal] 161(6), pp.618-619.

10.1001/archpedi.161.6.618-b.

Waldman, M., Nicholson, S. and Adilov, N.,

2006. Does television cause autism? NBER

Working Paper 12632., [online] Available at :

https://www.nber.org/papers/w12632,. [Accessed

: 1 July 2018].

Wilson, B. J., 2008. Media and children's

aggression, fear, and altruism. Future Child, [e-

journal] 18(1), pp.87-118. 10.1353/foc.0.0005.

A Preliminary Study of Screen-media, Empathizing, and Systemizing in Children

375