The Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Developing

Emotion Regulation Skill for Adolescent with Intellectual Disability

Shahnaz Safitri, Rose Mini Agoes Salim, and Pratiwi Widyasari

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Indonesia, UI Campus, Depok, Indonesia

Keywords: Dialectical Behavior Therapy; Emotion Regulation; Intellectual Disability.

Abstract: Intellectual disability is characterized by significant limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive

behaviour that appears before the age of 18 years old. The prominent impacts of intellectual disability in

adolescent are failure to establish interpersonal relationships as socially expected and lower academic

achievement. Meanwhile, it is known that emotion regulation skill has a role in supporting the functioning

of individual, either by nourishing the development of social skill as well as by facilitating the process of

learning and adaptation in school. This study aims to look for the effectiveness of Dialectical Behaviour

Therapy (DBT) in developing emotion regulation skill for adolescent with intellectual disability. DBT’s

special consideration toward clients’ social environment and their biological condition is foreseen to be the

key for developing emotion regulation capacity in adolescent client with intellectual disability. Through

observations on client’s behaviour, conducted before and after the completion of DBT intervention program,

it was found that there is an improvement in client’s knowledge and attitude related to the mastery of

emotion regulation skills. In addition, client’s consistency to actually practice emotion regulation techniques

over time is largely influenced by the support received from the client’s social circle.

1 INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is a transitional period of development

starting from the age of 10 into adulthood. The

distinctive feature of adolescents is that their

emotional state is rapidly fluctuated over time in

response to their environment. It is said that this

state of emotional fluctuation makes them

vulnerable to anger and aggressive behaviour when

facing unpleasant situations (Papalia, Olds, and

Feldman, 2010). Furthermore, adolescents also tend

to be more reactive to their surrounding and more

often feel negative emotions. Such condition

becomes a potential for them to engage in a

relational conflict, be it with parents, peers, and

other social circles (Gross, 2012).

Mastering social skill supports the adolescents

on their adaptation to everyday social situations

(Gross, 2012). The need to adapt adequately is of

particular concern for adolescent with intellectual

disabilities. Intellectual disability is a condition

marked by significant limitation in intellectual

function and adaptive behaviour which emerging

before the age of 18 years old (Hallahan and

Kaufman, 2006). Commonly found in adolescents

with intellectual disability is a typical growth of

physical development, in which it is in accordance to

the chronological age. However, their cognition and

social emotional aspects are underdeveloped

compare to their peers. It is stated that this

developmental discrepancy has occurred since the

early onset of development and continues into

adulthood (Barbosa, 2007; Pereira and Faria, 2015).

Because of their developmental discrepancy,

adolescents with intellectual disability often receive

unrealistic social expectations in their everyday life.

They are often seen by others as high functioning

individuals who are capable of an adequate social

interaction, given that their physical appearance is

just like a typical person of their age. As no surprise,

adolescents with intellectual disability tend to be

unable to meet the expectations in their conduct of

social interaction (Marinho, 2000; Pereira and Faria,

2015). The combination of delayed development in

both cognitive and social emotional aspect leads to

their failure of building interpersonal relationship as

expected. This failure leads to an isolation and

rejection by peers, which is the main cause of stress

and negative self-concept in adolescents with

Safitri, S., Salim, R. and Widyasari, P.

The Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Developing Emotion Regulation Skill for Adolescent with Intellectual Disability.

DOI: 10.5220/0008589303510359

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings (ICP-HESOS 2018) - Improving Mental Health and Harmony in

Global Community, pages 351-359

ISBN: 978-989-758-435-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

351

intellectual disability (Blackwell, 1979, Hauser-

Cram and Krauss, 2004).

Another study by Wiltz (2005) suggests that the

majority of individuals with intellectual disability

often have a limited number of friends. Furthermore,

their friendship tends to be full of conflict and

unstable. It is mentioned that this friendship is

difficult to maintain due to their difficulty in social

skill, such as translating social signals of facial

expression. This makes individuals with intellectual

disability become vulnerable to loneliness, and in

the extreme case they can suffer from depression

(Heiman, 2000 in Wiltz, 2005).

In general, as adolescent grow with increasing

age, followed by development in cognitive abilities,

they are gradually be more able to regulate their

emotions in order to fit themselves in daily social

and moral norms (Papalia, Olds, and Feldman,

2010). Unlike adolescent in general, the chronic

developmental discrepancy in adolescents with

intellectual disability becomes a major factor for

their difficulty in developing another skill, one of

them is on regulating emotion. Furthermore, it is

known that the difficulty in regulating emotions is

the reason for their inadequate social interaction

(Baurain and Grosbois, 2012). This dynamic shows

that emotion regulation skill is important for

adolescents with intellectual disability to adapt to

social environment (Gross, 2012).

Emotional regulation is defined as an individual

process for actively adjusting their emotional

experiences by considering the type of emotions, the

time of and for experiencing emotions, and how

those emotions are channelled (Gross and Thomson,

2007). It is said that emotion regulation is part of the

overall individual adjustment to his/her external

environment (Baurain and Grosbois, 2012).

Furthermore, emotion regulation is also part of a

general self-regulation, a process that allows

individuals to flexibly respond to changing

environmental context but still in line to their pursuit

of goals (Mennin and Fresco, 2014).

The emotion regulation skill promotes the

development of individual social skills. It is known

that mastering emotion regulation contributes to the

formation of social competencies in adolescents,

both for short-term and long-term period

(Einsenberg, 1997 in Gumora and Arsenio, 2002).

Especially in adolescents with intellectual disability,

emotion regulation skill is needed to develop their

underdeveloped social skills in order to blend in

with society and avoid social isolation, bullying, and

victimization. In addition, the mastery of social

skills supports the individual not to display an

aggressive and violent behaviour, which is also

commonly found in individuals with intellectual

disability (Hauser-Cram and Krauss, 2004; O'clare,

Waasdorp, Pas, and Bradshaw, 2015).

In accordance with developing social

competence, a well-developed emotion regulation

skill is also known to facilitate the creation of a

positive relationship between students and teachers.

This then becomes a contributing factor in enabling

students to smoothly learn from the teachers and

build their achievement motivation (Graziano,

Reavis, Keane, and Calkins, 2007). The lack of

cognitive ability in adolescent with intellectual

disability makes learning difficult for them and

brings out negative emotions (Gumora and Arsenio,

2002). Therefore, their capacity to regulate those

negative emotions foster them to survive the

learning process regardless their cognitive

constraints (Denham, Basset, Mincic, Kalb, Way,

Wyatt, and Segal, 2012). Without emotion

regulation, their learning achievement and academic

adjustment tend to be low. In fact, school adjustment

is known as a predictor for their life adjustment in

the long run (Eisenhower, Baker, and Blacher,

2007).

All these description shows that there is a need

for adolescent with intellectual disabilities to

improve emotion regulation skill. By definition,

emotion regulation involves the process of

individual actively adjusting his/her experience by

considering the type of emotion, the time of

experience, and how the emotion is channelled

(Gross and Thomson, 2007). Thus, the basis of

emotion regulation skill is the ability to distinguish

the types of emotion (Linehan, 1993 in McWilliams,

deTerte, Leathem, Malcolm, and Watson, 2014).

The ability to differentiate emotion is also a part of

an important social skill, since it facilitates

individual to behave appropriately regardless the

current emotional state. Individual who is more

aware of his/her emotional state tends to be easier to

regulate the emotion experienced (Gross, 2006).

Research by Baurain and Grosbois (2012)

suggests that individual with intellectual disability

have a delayed emotion regulation skill development

compare to the peers. This delay explains their lesser

frequency and quality of social behaviour, in which

it continues throughout adulthood. On the other

hand, this study provides an insight that that the

ability to regulate emotion in individual with

intellectual disability improves gradually as they get

older. Thus, a program to enhance the emotion

regulation skill in individual with intellectual

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

352

disabilities is applicable to optimize their

capabilities.

There are numbers of therapy that specifically

aim to develop emotion regulation skill, such as

Emotion Regulation Therapy (ERT), Attention

Modification, Affect Regulation Training (AFT),

Mindfulness Training (MT), and Dialectical

Behaviour Therapy (DBT). All of these therapies

focus on empowering the individual's ability to

master emotion regulatory skill using cognitive and

behavioural strategies (Gross, 2014). Nevertheless,

Attention Modification, AFT, and MT require

clients to possess an adequate cognitive function to

concentrate to the environmental stimulus; so that

they can manage the emotions associated with the

stimulus (Berking and Schwarz, 2014; MacLeod and

Grafton, 2014; Farb, Anderson, Irving and Segal,

2014). Furthermore, the ERT technique demands a

lot of higher order thinking to know one’s own value

in the process of regulating emotions (Mennin and

Fresco, 2014). Meanwhile, individual with

intellectual disability has limitation in their cognitive

function (Hallahan and Kaufman, 2006).

In contrast to other therapies, DBT views the

difficulty for regulating emotion as an implication of

various biological and non-supportive environmental

factors (Lew, Matta, Trip-Tebbo, and Watts, 2006).

Thus, DBT is particularly concerned about how

environmental and individual histories play a role in

his/her ability to regulate emotion (Gross, 2014).

Biological factors include cognitive capacity; while

environmental factors, among others, are the lack of

opportunity and feedback from the social

environment for individual to exercise emotion

regulation (Njardvik, Matson, and Cherry, 1999).

DBT's special consideration to personal factors

makes this therapy an appropriate alternative to be

delivered to individual with intellectual disability. In

DBT, the therapeutic emphasis is placed on the

positive and non-judgmental climate. Furthermore,

DBT focuses on preparing clients to be able to stand

for themselves using the skills taught, while

ensuring the availability of coaches that clients can

rely on in times of crisis (Lew, Matta, Trip-Tebbo,

and Watts, 2006). This is in line with the spirit of

education for individual with intellectual disability,

which is to develop their independence while

considering their magnitude of disability. It is

known a more severe disability require more

intensive assistance (Mangunsong, 2009). This

concept is in accordance with the characteristic of

adolescents with intellectual disability who still

require guidance when necessary.

Furthermore, DBT is also taking into account the

environmental factors that shape individual's life

history related to the opportunity to exercise emotion

regulation skill (Lew, Matta, Trip-Tebbo, and Watts,

2006). It is said that individual with intellectual

disability are often live a condition of over-

protective family, so that they have no experience

for decision making. Furthermore, individual

surrounding is often unresponsive to emotional

expression except for negative emotional display.

Thus, the individual gets reinforcement for this

negative emotion expression. DBT through one of

its several modes of intervention - structuring client's

environment - responds this environmental challenge

in relation to developing emotion regulation skill

(Lew, Matta, Trip-Tebbo, and Watts, 2006). This is

done by involving family members in training, as

well as re-arranging clients’ room with several tools,

such as journal of daily emotional state. These

practices are also in line with the principle of

education in individual with intellectual disability, in

which modification of space is sometimes needed

for the learning process (Mangunsong, 2009).

This paper describes the process of conducting

DBT in special population of adolescent with

intellectual disability. It is known that DBT has five

modes of intervention, which are individual therapy,

skills training, coaching in crisis, structuring the

environment, and consultation team. However, it is

said that skill training is the most essential element

of DBT among all other modes (Soler, et.al, 2009).

Another study by Sakdalan, Shaw, and Collier

(2010) found that skill training is the only mode of

all DBT intervention that can be delivered solely

without other modes. Based on the information

gathered, we aim to test the DBT's skill training

effectiveness for improving emotion regulation skill

in adolescent with intellectual disability. As far as

we concern, this is the first study to seek out the skill

training effectiveness in the context of client with

the mentioned characteristic.

2 METHOD

2.1 Research Question and Hypothesis

This study aims to answer if Dialectical Behavior

Therapy technique can be used to improve emotion

regulation skill in adolescent with intellectual

disability. We propose a hypothesis that Dialectical

Behavior Therapy technique is effective to improve

emotion regulation skill in adolescents with

intellectual disability.

The Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Developing Emotion Regulation Skill for Adolescent with Intellectual Disability

353

2.2 Research Design

We use single subject design in which the

measurement to answer the research question is

conducted to one subject. In a single subject design,

the researcher focuses on the behaviour the subject

raises before the program is given and after the

program is completed. (Gravetter and Forzano,

2009). Therefore, there is period of baseline

observation being conducted prior to the delivery of

intervention program. This is done to get an accurate

portrait of subject’s behaviour in daily life in respect

to the his/her capacity to regulate emotion.

2.3 Participant

The subject is adolescent with intellectual disability

with difficulty in emotion regulation skill. By

definition, the characteristic is applied to those in

age of 10 years old to early twenties (Papalia, Olds,

and Feldman, 2010). In addition, they possess an

intellectual disability in which there is significant

limitation of intellectual function and adaptive

behaviour manifested through conceptual, social,

and practical adaptive abilities (Hallahan and

Kaufman, 2006). A girl aged 16 years old with

intellectual disability is referred to the researcher

with characteristic of having difficulty in social

interaction due to the inability to regulate emotion.

2.4 Overview of Intervention Program

In providing DBT to individual with intellectual

disability, there are number of challenges to be faced

(Lew, Tripp-Tebo, and Watts, 2006). Those

challenges are as follow:

1. The standard DBT practice is constrained by

the clients' language capacity, in which they

tend to communicate in a much simpler

vocabulary.

2. Some clients with intellectual disability tend to

be unready for a group activity.

Charlton and Dykstra (2011) describes that the

adaptation of DBT is a must. One of the ways is by

conveying information during intervention using

various modalities. In this study we use various

materials and activities, which are ranging from

working on coloured worksheet, watching cartoon

videos, and doing physical movement. In addition, a

simple language is required to teach the client during

intervention, so that it is easier for them to

understand what is taught by the therapist. We use a

simple vocabulary to speak, and switch the word in

worksheet with a relevant image to serve as a

symbol for the client to understand the meaning. The

use of symbol is due to the client's inability to read.

Furthermore, it is said that the materials

containing information for client need to be tailored

to attract the attention and facilitate understanding

(Charlton and Dykstra, 2011). This is done by

containing the images of the client's idol in every

material given to maximize her excitement to learn.

Bailie and Slater (2014) adds that the content of the

intervention needs to be conveyed by linking to what

client has already known. The content must also be

in line with what is faced by clients in their daily

life, so that they can apply the skill directly in daily

affair. Therefore, we observe the subject and

interview her family to gain a deeper understanding

of her daily life before the intervention is conducted.

Intervention also needs to be implemented in a

simple therapeutic structure using concrete

activities. A clear rule is also needed during client's

participation throughout the intervention process.

The therapist also needs to be more active and

directive to the client compare to teaching client

without disability. Throughout the intervention

process, repetition of the material taught becomes

important and is part of the overall intervention

structure. Therefore, there is a need for a special

time allocation to review the lessons and various

situations to apply the emotion regulation skill being

taught, in order to facilitate client in making

generalization of the knowledge and skills (Charlton

and Tallant, 2003 in Charlton and Dykstra, 2011).

Another DBT adaptation is that the therapist

should involve client's family members, teachers, or

other caregivers into the intervention process. This is

done to ensure that caregivers can practice the same

skills as learned by the client. It is beneficial for

clients if their caregivers gain these same knowledge

and skills to further act as their coaches and facilitate

mentorship in everyday life (Charlton and Dykstra,

2011). Therefore, a special session is held to teach

the client's mother and teachers all the programs

activities and objectives. They are also given a

responsibility to ensure the client do her homework

and fill the journal designed by the researcher to

observe the client's progress in home and in schools.

2.5 The Program Objective

In the standard DBT's skills training, there are 10

objectives to be reached. The mastery of the first 6

objective of the training is a prerequisite to be

further able in mastering a more advanced emotion

regulation skill (McKay, Wood, and Brantley,

2007). Therefore, this study focuses on targeting the

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

354

first 6 objectives to be adopted as the program's

goal. The details are as follows:

1. Subject is able to recognize various types of

basic emotions.

2. Subject is able to recognize their own

emotions.

3. Subject understands the process of emotion

formation.

4. Subject is able to manage negative emotions.

5. Subject knows how to increase the emergence

of positive emotions.

6. Subject knows the factors that affect the

emotion regulation process.

2.6 Program's Targeted Behaviour

In general, the program is considered successful if

there is an increase in the emotion regulation skill

shown by the subject. It is indicated by several

indicators:

1. Subject can identify the types of basic

emotions

The subject is said to be able to identify the

types of basic emotions when she can name all

the 6 different basic emotion as shown is the 6

coloured emotion cards. Otherwise, subject

need also to be able to choose the right emotion

card according to type of emotion mentioned

by researcher.

2. Subject can identify the emotions they feel in

real situations.

The subject is said to be able to identify the

emotions she feels when she can tell her

emotional experience according to the emotion

card given by researcher. This applies to all six

basic emotions.

3. Subject understands the process of emotion

formation, by identifying the situation that

cause emotion, the background thoughts, the

emotion emerged, and the action to respond to

situations.

Subject is said to be able to understand the

process of emotion formation when she can

accurately arrange a series of display card that

contain image/symbol associated with the four

stage of emotion formation. Furthermore,

subject also needs to tell a story of six basic

emotions emergence by matching the story

card to the relevant emotional sequence card

arranged first. The story is both gathered from

the subject experience and also from 6 cartoon

videos containing different emotional display.

4. Subject can manage the negative emotions

experience

The subject is said to be able to manage

negative emotions if she can demonstrate the

correct "stop-think-relax" technique in the

proper sequence as taught in the program.

5. Subject knows how to improve his/her positive

emotions

The subject is said to know how to improve her

positive emotion when she can mention all

different activities taught in generating positive

emotions. She needs to remember the activities

without any clue given.

6. Subject knows the vulnerability factor in the

process of emotion regulation

The subject is said to know the factors affected

emotion regulation when she can mention the

meaning of the symbolic images, given as a

work-sheet, that refer to these factors.

2.7 Program Implementation

The intervention is conducted by having one session

a day to make the learning conducive to the client's

capacity to learn. The program details are listed in

the Table 1.

In practice, we found that the session 2 of the

intervention needed repetition, since the subject

cannot answer the review questions asked on the

following day. In addition, the post-test 2 of the

study was failed to be delivered on schedule due to

the client's health condition. Therefore, the aim to

seek out if the subject's attainment of program

indicator is still intact was done by relying on the

observational worksheet filled out by the client's

mother at home. In conclusion, the intervention was

executed as an 8 days intervention as planned but

with different sequences.

2.8 Data Analysis

As in standard DBT's skill training, this research use

observation as a method to measure the completion

of program's goal and test the intervention

effectiveness. Observation takes place before and

after intervention is held, focusing on achievement

of behavior indicator. The score is given to the

subject for every successful attainment on program's

objectives. The percentage of achievement score

before and after intervention is then compared to

grab the picture of program effectiveness in

improving subject's emotion regulation skill. The

additional data analysis is done using a behavioral

checklist filled out by the mother and teacher of the

clients.

The Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Developing Emotion Regulation Skill for Adolescent with Intellectual Disability

355

Table 1: Program Session(s) & Objective(s)

Session

Objective

Pre-test &

Program

Orientation

The gather subject's baseline level of

emotion regulation skill in respect to

behavior indicator.

To familiarize subject with the

intervention setting, signing contract

containing rules to be respected by

the client

To teach the mother and teacher

about the program, including

objectives, activities, and materials.

The behavioral checklist is also

explained to be further filled by

them.

Session 1

To review the rules of learning

To identify the types of basic

emotions

Session 2

To review the previous session

material

To review the homework given

To identify the emotions participant

feel in real situation

To understand the process of

emotion formation

Session 3

To review the previous session

material

To review the homework given

To manage the negative emotions

experience

Session 4

To review the previous session

material

To review the homework given

To know how to improve positive

emotions

Session 5

To review the previous session

material

To review the homework given

To know the vulnerability factor in

the process of emotion regulation

Post-test 1

The gather subject's attainment of

emotion regulation skill in respect to

behavior indicator.

Session

Objective

Post-test 2

The seek out if the subject's

attainment of emotion regulation

skill in respect to behaviour indicator

is intact

3 RESULTS

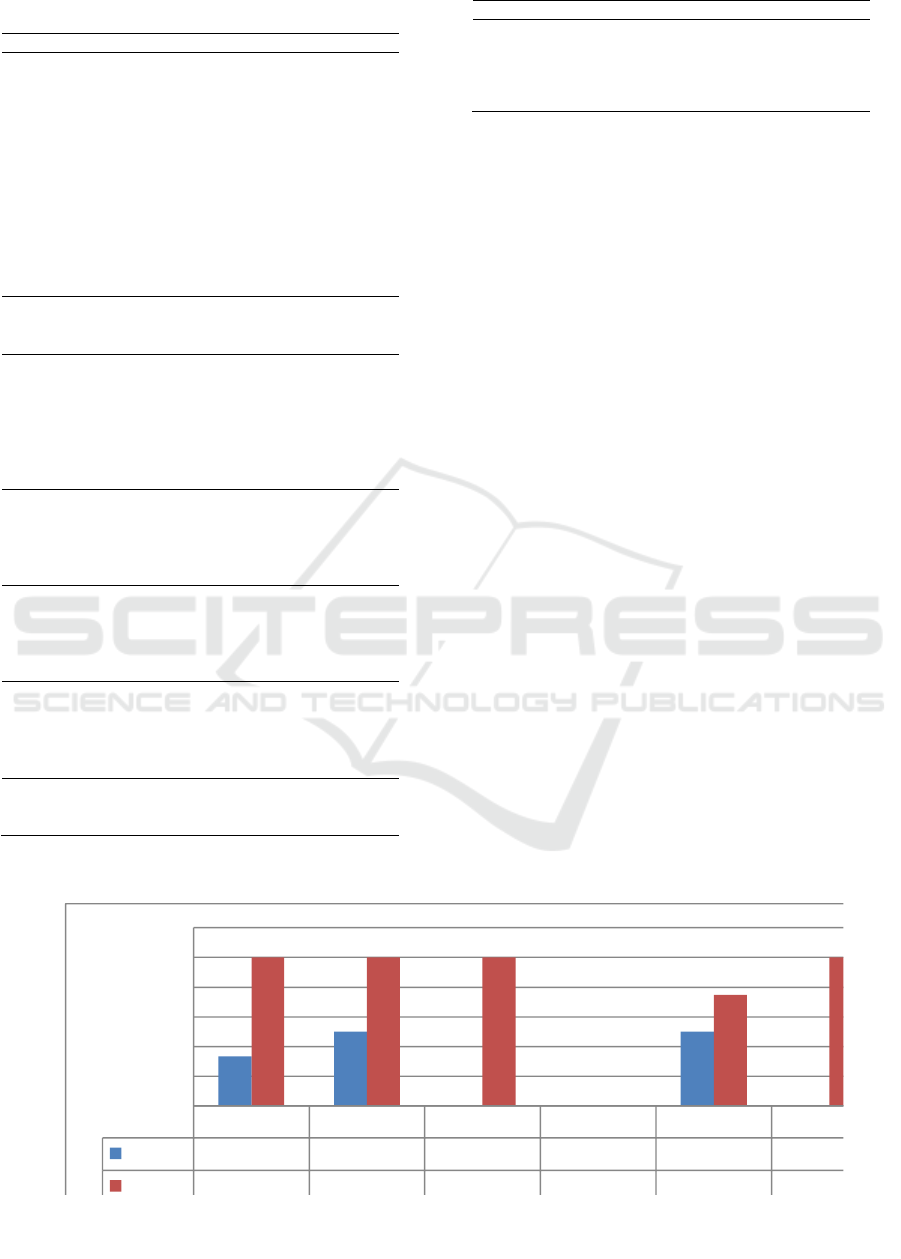

The Figure 1 is that summarizes the differences of

client's percentage on achievement score before and

after the intervention related to the behaviour

indicator.

From the graph, we can see that there are

differences in subject's achievement percentage

score of emotional regulation skill before and after

intervention conducted. Prior to the intervention,

subject obtains a total score of 9 out of 27 with the

resulting percentage of 33.33%. While in post-test,

subject gets the score of 24 which mean that she gets

a percentage of 88.89%. Therefore, there is an

increase in the percentage score by 55.56%, which

indicate that there is an increase in subject level of

emotion regulation skill. The data obtained shows

that the increase occurs on five out of six program

objectives.

4 DISCUSSION

Charlton and Dykstra (2011) revealed that language

adaptation in the implementation of the DBT is a

must so that subject with intellectual disability can

easily understand the learning lesson and then apply

the knowledge. In this study, language adaptation

becomes one of the keys in enabling the subject to

capture the information provided by researcher.

Indicator 1

Indicator 2

Indicator 3

Indicator 4

Indicator 5

Indicator 6

Pretest

33.33

50

0

0

50

0

Postest

100

100

100

0

75

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

Percentage

Figure 1: Comparison of Client Percentage Score Before and After the Intervention

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

356

Some examples of language adaptation are

"emotions" as "feelings," "emotional regulation," as

"regulating feelings," "actions" as "what to do," and

so on. The selected word is chosen from the

preliminary observation of client's vocabulary

repertoire. Thus, the creativity of the researcher in

determining the right vocabulary to convey the

lesson in accordance with the material is crucial.

Charlton and Dykstra (2011) argues that content

in the program should be as relevant as possible to

the daily life of the clients to facilitate their

application of the skill taught. Bailie and Slater

(2014) added that the intervention program should

relate the new information provided to what was

previously known by the client. In this program, the

overall content reviewed is specifically tailored to

the subject's daily life. For example, a case study of

a person being scolded by parents, ridiculed by

friends, and travelling to Bali are given; where they

are all known as situations that cause the subject to

experience certain emotional reaction. For that

purpose, collecting baseline data before the delivery

of program becomes important to determine which

case should be raised in the program. The suitability

between the case raised and the subject previous

experiences makes it easy to draw the subject's

attention to the material and to gain understanding.

Lew, Tripp-Tebo, and Watts (2006) mentioned

that materials in the intervention program need to be

tailored to attract the attention of clients. Given the

condition of the client is not able to read yet, the

material in then given by using images with various

colours. The use of image builds the impression of a

fun learning process to the client, and makes it easy

for her to identify and associate the images with

explanations given by the researcher about the

meaning. Furthermore, the attractiveness is enforced

through the inclusion of self and family portraits in

the instrument. It becomes easier for subject to

recognize the image and she can immediately

associate between what she knows based on her

experience with the material provided. In addition,

the use of self and family portrait makes the subject's

learning process in line with the individual approach

which is advisable in the educational process for

individuals with special needs (Mangunsong, 2009).

Repetition of material to subject with intellectual

disabilities is important and also forms the structure

of the overall implementation of intervention

(Charlton and Tallant, 2003 in Charlton and Dykstra,

2011). Furthermore, repetition is also one of the

main principles in teaching individual with

intellectual disabilities (Hallahan and Kaufman,

2006) related to their characteristic of memory

deficiency. Throughout the program, the repetition

of the material that has been learned is done in each

session. On the other hand, the subject complained

several times that she was bored with the repetition

because she already knew about the material. In this

case, we see that the process of review of the

material needs to be done with a variety of

activities/methods to foster the motivation of the

client in order to avoid boredom.

Limitation of this study lies in the physical

condition of the subject who had shown the

symptoms of sickness in the final session of the

program. In respect to the failure of practicing the

act of managing negative emotion (using stop-think-

relax method), the main constraint lies in the nature

of the stop-think-relax technique. This technique

requires optimal physical condition for the

individual who practice it. During the program,

subject finds it difficult to practice relax techniques-

in which she needs to inhale and exhale deeply –

since she has cold. Therefore, attention to the

physical condition of the subject for program

implementation becomes crucial. In addition,

considering another type of negative emotion

regulating techniques is advisable. As a note, the

technique should be concrete enough and easily

implemented by the individual in respect to their

disability (Mangunsong, 2009).

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study aims to test the effectiveness of

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy in improving the

emotion regulation skill in adolescents with

intellectual disability. Based on the result obtained,

we see that the program is effective to improve the

client's emotion regulation skill based on the

behaviour indicator. Through observation made on

the subject's behaviour after the program, it was

found that the program succeeded in providing new

knowledge to the subject about the benefits of

excelling in emotion regulation skill, the types of

emotions, the process of emotion emergence, the

procedure for managing negative emotions, the

activities to induce positive emotions, and factors

affecting emotion regulation. Furthermore, the

program also succeeds in changing the views or

attitudes of the subject regarding the importance of

managing emotions in everyday life, especially in

terms of changing bad habits that foster vulnerability

for experiencing negative emotions. Nevertheless,

further tracking is required to seek out if the

program is successful in altering the actual

The Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Developing Emotion Regulation Skill for Adolescent with Intellectual Disability

357

behaviour of the subject to regulate the negative

emotion using the techniques taught.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study cannot be successfully done without the

support of Sekolah Luar Biasa Ulaka Penca for

giving the required time and place to conduct the

intervention to the client. Cooperation displayed by

the subject's family member is also the main factor

for the subject's successful completion of the

program. To further clarify, this research received

no specific grant from any funding agency,

commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

Baillie, A. and Slater, S., 2014. Community dialectical

behaviour therapy for emotionally dysregulated

adults with intellectual disabilities. Advances in

mental health and intellectual disabilities, 8(3),

pp.165-173.

Barnicot, K., Gonzalez, R., McCabe, R. and Priebe, S.,

2016. Skills use and common treatment processes

in dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline

personality disorder. Journal of behavior therapy

and experimental psychiatry, 52, pp.147-156.

Baurain, C. and Nader-Grosbois, N., 2012. Socio-

emotional regulation in children with intellectual

disability and typically developing children in

interactive contexts. ALTER-European Journal of

Disability Research/Revue Européenne de

Recherche sur le Handicap, 6(2), pp.75-93.

Berking, M. and Schwarz, J., 2014. Affect regulation

training. Handbook of emotion regulation, 2.

Blackwell, M.W. 1979. Care of the Mentally Retarded.

Little, Brown, and Company. USA.

Charlton, M. and Dykstra, E.J., 2011. Dialectical

behaviour therapy for special populations:

Treatment with adolescents and their caregivers.

Advances in mental health and intellectual

Disabilities, 5(5), pp.6-14.

Denham, S.A., Bassett, H., Mincic, M., Kalb, S., Way, E.,

Wyatt, T. and Segal, Y., 2012. Social–emotional

learning profiles of preschoolers' early school

success: A person-centered approach. Learning

and individual differences, 22(2), pp.178-189.

Eisenhower, A.S., Baker, B.L. and Blacher, J., 2007. Early

student–teacher relationships of children with and

without intellectual disability: Contributions of

behavioral, social, and self-regulatory competence.

Journal of school psychology, 45(4), pp.363-383.

Espelage, D.L., Rose, C.A. and Polanin, J.R., 2015.

Social-emotional learning program to reduce

bullying, fighting, and victimization among middle

school students with disabilities. Remedial and

special education, 36(5), pp.299-311.

Farb, N.A., Anderson, A.K., Irving, J.A. and Segal, Z.V.,

2014. Mindfulness interventions and emotion

regulation. Handbook of emotion regulation,

pp.548-567.

Gravetter, F.J. and Forzano, L.A.B., 2018. Research

methods for the behavioral sciences. Cengage

Learning.

Graziano, P.A., Reavis, R.D., Keane, S.P. and Calkins,

S.D., 2007. The role of emotion regulation in

children's early academic success. Journal of

school psychology, 45(1), pp.3-19.

Gross, J.J. 2014. Handbook of emotion regulation. The

Guilford Press.

Gross, J.J and Thomson, R.A. 2007. Emotion regulation:

Conceptual foundations. Handbook of Emotion

Regulation . The Guilford Press.

Gumora, G. and Arsenio, W.F., 2002. Emotionality,

emotion regulation, and school performance in

middle school children. Journal of school

psychology, 40(5), pp.395-413.

Hallahan, D.P. and Kaufman, J.P. 2006. The exceptional

learner: Introduction to special education.

Pearson Education.

Hauser-Cram, P., Krauss, M.W. and Kersh, J., 2004.

Adolescents with developmental disabilities and

their families. Handbook of adolescent

psychology, 1, pp.589-617.

Lew, M., Matta, C., Tripp-Tebo, C. and Watts, D., 2006.

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) for individuals

with intellectual disabilities: A program

description. Mental health aspects of

developmental disabilities, 9(1), p.1.

Linehan, M. M. 1993. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of

borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

Mangunsong, Frieda. 2009. Psikologi dan pendidikan

anak berkebutuhan khusus. LPSP3.

MacLeod, C. and Grafton, B. 2014. Affect regulation

training. Handbook of emotion regulation. The

Guilford Press.

McKay, M., Wood, J.C. and Brantley, J., 2010. The

dialectical behavior therapy skills workbook:

Practical DBT exercises for learning mindfulness,

interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation

and distress tolerance. New Harbinger

Publications.

McWilliams, J., de Terte, I., Leathem, J., Malcolm, S. and

Watson, J., 2014. Transformers: a programme for

people with an intellectual disability and emotion

regulation difficulties. Journal of intellectual

disabilities and offending behaviour, 5(4), pp.178-

188.

Mennin, D.S. and Fresco, D.M. 2014. Emotion regulation

therapy. Handbook of emotion regulation. The

Guilford Press.

Njardvik, U., Matson, J.L. and Cherry, K.E., 1999. A

comparison of social skills in adults with autistic

disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not

otherwise specified, and mental retardation.

ICP-HESOS 2018 - International Conference on Psychology in Health, Educational, Social, and Organizational Settings

358

Journal of autism and developmental disorders,

29(4), pp.287-295.

O’Brennan, L.M., Waasdorp, T.E., Pas, E.T. and

Bradshaw, C.P., 2015. Peer victimization and

social-emotional functioning: a longitudinal

comparison of students in general and special

education. Remedial and special education, 36(5),

pp.275-285.

Papalia, D.E., Olds, S.W., and Feldman, R.D. 2010.

Human development. The McGraw-Hill

Companies

Pereira, C.M.G. and de Matos Faria, S.M., 2015. Do you

feel what I feel? Emotional development in

children with ID. Procedia-Social and behavioral

sciences, 165, pp.52-61.

Saarni, C., Campos, Camras, J., and Withering, D. 2006.

Emotional development: Action communication

and understanding. Handbook of Child

Psychology. Wiley. N

Sakdalan, J.A., Shaw, J. and Collier, V., 2010. Staying in

the here‐and‐now: A pilot study on the use of

dialectical behaviour therapy group skills training

for forensic clients with intellectual disability.

Journal of intellectual disability research, 54(6),

pp.568-572.

Soler, J., Pascual, J.C., Tiana, T., Cebrià, A., Barrachina,

J., Campins, M.J., Gich, I., Alvarez, E. and Pérez,

V., 2009. Dialectical behaviour therapy skills

training compared to standard group therapy in

borderline personality disorder: a 3-month

randomised controlled clinical trial. Behaviour

research and therapy, 47(5), pp.353-358.

Wiltz, J.P., 2005. Identifying factors associated with

friendship in individuals with mental retardation

(Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University).

The Effectiveness of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Developing Emotion Regulation Skill for Adolescent with Intellectual Disability

359