Is The Quality of Business Incubator Programs Capable of Boosting

Entrepreneurial Orientation and Intention at Higher Education?

M. Ariza Eka Yusendra

1

, Niken Paramitasari

1

, Ribhan

2

, Ayi Ahadiyat

2

1

Institute of Informatics & Business Darmajaya, Lampung, Indonesia

2

Lampung University, Lampung, Indonesia

Keywords: Business Incubator, Entrepreneurial Intention, Entrepreneurial Orientation, The Quality of Incubation

Programs, Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control

Abstract: This research attempts to expand on and explore the formation model of Entrepreneurial Orientation &

Intention by testing the effect of The Quality of Incubator Program that is mediated by Perceived

Entrepreneurial Self-Control. The model expanded here is a synthesis of Entrepreneurship Theory, The

Theory of Planned Behavior and Human Capital Theory. The research model was empirically tested on

university business students in Indonesia with a sample of 200 respondents and then analyzed using

Structured Equation Modeling. Business incubation programs in the form of quality services such as

Infrastructure Provider, Business Services, Financing Provider and People Connectivity, can produce

business students that possess a variety of business skills that generate confidence and a positive self-

perception in conducting business. Later this confidence and positive self-perception can generate students

that are entrepreneurial oriented—innovative, proactive, risk-taking, to the extent that they will be capable

of increasing the intention in conducting business

1 INTRODUCTION

Universities believe that business incubator is a

strong tool for promoting innovation and

entrepreneurship through a variety of activities like:

business development process monitoring,

management mentoring, and product/service life

cycle analysis for a business all the way up until the

exit strategy. (Aerts et al., 2007). The purpose of

these incubation activities is as learning media for

new ventures, a forum for exchanging ideas,

receiving psychological support, maintaining

partnerships, and establishing business relationships

with outside entities (Li et al., 2017). If business

incubator can be managed well, it will certainly

produce high quality business programs that can

help students gain self-confidence and feel capable

of conducting business. This self-confidence and

feeling of capability will also later encourage

prospective entrepreneurs in the formation of their

interest and business orientation. Students who have

high motivation and business orientation certainly

will actively participate in the creation of businesses

or innovations and have interest in developing

business tools in order to create a business

ecosystem within the university (De Jorge‐Moreno

et al., 2012).

Unfortunately, at this time there is very little

research that presents the effect of quality business

incubator programs on entrepreneurial orientation

and intention at the higher education. Researchers

such as Sondari (2014) and Usaci (2015)have indeed

focused their studies on the entrepreneurial intention

of students at the higher education, but have not

clearly included inputs in the form of training

activities and business– choosing to discuss the

mental indicators of an entrepreneur. Marques et al.

(2018) and Alvarez et al. (2006) have also done

research about business orientation at the higher

education, but have placed emphasis on curriculum,

learning methodology, or the impact of various

demographics. Although much research has been

done on The Theory Of Planned Behavior, to date

none has specifically focused on the role of

entrepreneurial perceived Self-Control as having a

causal relationship with the formation of

entrepreneurial orientation and intention– which

have a significant impact compared to other TPB

dimensions (Mei et al., 2015).

Eka Yusendra, M., Paramitasari, N., Ribhan, . and Ahadiyat, A.

Is The Quality of Business Incubator Programs Capable of Boosting Entrepreneurial Orientation and Intention at Higher Education?.

DOI: 10.5220/0008439703090318

In Proceedings of the 4th Sriwijaya Economics, Accounting, and Business Conference (SEABC 2018), pages 309-318

ISBN: 978-989-758-387-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

309

Several studies that have been presented show

that the development models for the formation of

entrepreneurial orientation and intention through

business incubator programs are still very limited.

As a result, this research attempts to establish and

explore a development model for entrepreneurial

orientation and intention through the quality of

business incubator programs that is mediated by

entrepreneurial percieved Self-Control. This article

is comprised of several sections. Initially, we will

discuss the theories that form the basis for the

development model—particularly the theory of

planned behavior, human capital theory dan

entrepreneurship theory. Then a variety of

hypotheses will be tested in order to support

empirical model. In the second section we will

present a model that will test the goodness of fit and

be used to prove the hypothesis. The third section

will discuss the findings that fill in the research gaps

that have surfaced.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW &

HYPHOTHESES

2.1 Higher Education Business

Incubators and Their Business

Services

The business incubator is one organization

currently used as a strategic initiative to stimulate

and support economic growth through innovative

creation and company growth activities (Morgan,

2014). Many definitions of business incubator exist,

one of which comes from Blackburne and Buckley

(2017) stating that a business incubator is a

collaborative work space that offers tenants a variety

of intervention systems that add strategic value—in

business incubation, typically these include business

growth system monitoring and business support.

This system controls and connects a variety of

resources in order to facilitate successful business

growth, while at the same time limiting the

businesses potential failure expenses.

There are four services generally offered by

business incubators, the first of which is

Infrastructures Provider such as offices, meeting

rooms, laboratory facilities, internet, etc. The

purpose of this particular service is for economies of

scale, to reduce the business start-up costs and be

capable of creating a “professional and branded

look” (Hong et al., 2018). The next service is the

availability of business services like: strategy

consulting, market research, financial training, even

registering or licensing brands. The purpose of this

service is to assist in the process of a business’

management growth (van Weele et al., 2017). The

third service is to provide or develop partnerships

with those offering financing or capital funds

(Financial Provider & Facilitation). The purpose

here is to give leverage for new businesses so they

can receive finances for business growth (Wright,

2017). The fourth service is People Connectivity

which consists of mentoring and coaching services,

interaction with other entrepreneurs or even market

connections.

2.2 The Quality of Incubator

Programs, Entrepreneurial

Perceived Self-Control,

Entrepreneurial Orientation, and

Entrepreneurial Intention.

In business literature, entrepreneurship is defined

in various ways by experts. According to Woodside

et al. (2016), entrepreneurship is a process of

applying creativity and innovation to look for

opportunities and solve problems that are faced by

people in their daily lives. It can be said that the core

of entrepreneurship is creativity and innovation that

is capable of producing something new and valuable

for oneself and others. According to this definition,

entrepreneurship not only seeks personal gain but

must also have value for society (Murphy et al.,

2006). By using human capital theory, which states

that people are a form of capital just like other

forms, human resource development will be strongly

tied to the experience and exposure used to increase

productivity. As a result, entrepreneurship expertise

can be obtained through a process of socialization,

schooling, training, and workshops, all of which are

human capital investments (Adom and Asare-Yeboa,

2016). One method of improving a person’s

entrepreneurial investment capital is to implement a

Business Incubator program which is comprised of 4

basic services: Infrastructure Provider, Business

Services, Financial Provider and People

Connectivity. These four services collectively will

form the Quality of Incubator Programs to support a

person’s entrepreneurial capital (Li et al., 2017).

Based on this information, the researchers will

establish The Quality of Incubator Programs as

defined by a collective of entrepreneurial programs

comprised of Infrastructures Provider, Business

Services, Financial Provider and People

Connectivity that are part of a business incubator

SEABC 2018 - 4th Sriwijaya Economics, Accounting, and Business Conference

310

and capable of significantly improving the business

skills of the participants.

Moreover, when we talk about the intention to

engage in entrepreneurial activities, it cannot be

discussed apart from the theory of planned behavior.

There is one dimension that is closely tied to the

results of human investment that have been

conducted, and that is the creation of Perceived

Behavior Control (Murugesan and Jayavelu, 2015).

Perceived behavioral control is the perception of the

ease or difficulty of doing something and it

assumingly reflects past experience and an

anticipation of obstacles. Perceived behavioral

control is a function of control beliefs, which are

beliefs regarding factors that ease the doing of

something or make it more difficult, and the

perception of the weight of these factors (Ajzen,

1991). According to Mei et al. (2015) the result from

entrepreneurial human capital investment usually

expects that the individual subject can more easily

sole problems and, full or self-confidence, will be

capable of controlling a variety of entrepreneurial

initiatives in the form of Entrepreneurial Percieved

Self-Control. Because of this, Entrepreneurial

Percieved Self-Control can be defined as the

perception and belief of an individual regarding

his/her capability to engage in entrepreneurial

business processes with either ease or difficult.

From this information, a hypotheses can be

formed that represents the relationship between The

Quality of Incubator Programs and Entrepreneurial

Perceived Self-Control, as follows:

H1a: The Quality of Incubator Programs has a

positive impact on Entrepreneurial Perceived

Self-Control, in that the higher the quality of

incubator programs, the greater the

Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control of a

college student.

H1b: The Quality of Incubator Programs has a

positive impact on Entrepreneurial

Orientation, the higher the quality of

incubator programs, the greater the degree of

Entrepreneurial Orientation of a college

student.

H1c: The Quality of Incubator Programs has a

positive impact on Entrepreneurial Intention,

the higher the quality of incubator programs,

the greater the degree of Entrepreneurial

Intention for a college student.

2.3 Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-

Control and Entrepreneurial

Orientation

Entrepreneurship indicates the attitude, mindset,

and characteristics of someone who has the strong

desire to produce innovation real-world business and

develop it (Viinikainen et al., 2017). Entrepreneurs

therefore are those who: have initiative, organize,

and reorganize social and economic mechanisms to

alter resources and situations based on practical

evaluations and the acceptance of risk and potential

failure (Poole, 2018). These things demonstrate that

a successful entrepreneur must have an

entrepreneurial orientation defined by process,

practice, and decision making that has the three

aspects of entrepreneurship: innovation, taking

proactive steps, and the courage to take risks.

(Randerson, 2016).

Entrepreneurial orientation plays a prominent

role in the life of an entrepreneur to enable him/her

to understand and assist in business development

strategy and making the business more competitive

in the long term (Kamal et al., 2016). This is made

possible because innovation, as one of the

entrepreneurial orientation dimensions, can cause a

tendency for someone to develop new ideas and

processes that result in new products, services, or

even technologies. The ability to always be

proactive is also important for an entrepreneur

because it enables them to introduce new products

and services as soon as possible by taking advantage

of market opportunities. At the same time, the

courage to take risks is necessary to face obstacles

and exploit or take part in business strategies that are

likely full of uncertain outcomes. The primary

function of the importance of entrepreneurial

orientation is how to calculate and take risks

optimally. (Rodrigo-Alarcón et al., 2018) .

An important question that must be answered is

what encourages the development of entrepreneurial

orientation? A study by Montiel Campos (2017)

shows that if an entrepreneur has energy,

confidence, and mastery of skills, he/she will

typically be able to involve himself/herself in

activities that find new opportunities, grow the

market, and even optimize organizational processes

to be more adaptive to the times—in other words a

tendency to demonstrate an entrepreneurial

orientation. Other studies have suggested that

trainings, workshops, or consultations are capable of

increasing a person’s entrepreneurial orientation.

This fact shows that there is a possible relationship

Is The Quality of Business Incubator Programs Capable of Boosting Entrepreneurial Orientation and Intention at Higher Education?

311

between Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control and

Entrepreneurial Orientation.

From this information, a hypothesis can be

proposed representing the relationship between

Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control and

Entrepreneurial Orientation, as follows:

H2: Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control has a

positive impact on Entrepreneurial Orientation,

in that the higher the Entrepreneurial Self-

Control of a college student the greater the

degree of Entrepreneurial Orientation he/she

will have as well.

2.4 Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-

Control and Entrepreneurial

Intention

In recent years, many researchers have in

interested in doing studies on the entrepreneurial

intention of students at the higher education, which

among them are Ferrandiz et al. (2018); Herman and

Stefanescu (2017). Generally speaking,

entrepreneurial intention can be defined as the

awareness and conviction of an individual to

establish a new business or at least to establish one

in the future (Nabi et al., 2010). There are many

models that have been used to explain the formation

of this entrepreneurial intention. Some of the more

famous are Shapero’s Model of the Entrepreneurial

Event dan Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour

(Krueger and Carsrud, 1993). According to Krueger

et al. (2000), the formation of entrepreneurial

intention tends to approach a planned behavior

because the decision to become an entrepreneur is

not like classical conditioning, where one hides a

bell and people change their behavior to become an

entrepreneur. Rather the decision to become an

entrepreneur requires the weighing of many options

and is full of planning.

One of the antecedent variables in TPB that has a

great impact on entrepreneurial intention is

Perceived Behavioral Control (PCB), or the

subjective evaluation of a person regarding his/her

own ability to solve problems and achieve success in

a particular situation. Self-confidence regarding

one’s capacity in intelligence, patience, resilience,

and adaptability significantly impacts the formation

of intent, and its manifestation become the

entrepreneurial actions. The belief in this ability

does not always mean having the ability in a real and

measurable way, but is sometimes limited to a

personal evaluation of what can be accomplished

with the ability on has. The results of empirical

testing have shown the strength of this PCB impact

on the targeted behavioral intentions (Krueger et al.,

2011) .

From this information, a hypothesis that

represents the relationship between Entrepreneurial

Perceived Self-Control and Entrepreneurial

Intention, can be established as follows:

H3: Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control has a

positive effect on Entrepreneurial Intention,

such that the higher the Entrepreneurial Self-

Control of a college student, the higher the

degree of their Entrepreneurial Intention.

2.5 Entrepreneurial Orientation and

Entrepreneurial Intent

Based on the study conducted by Ismail et al.

(2015), presently universities are beginning to

reemphasize entrepreneurship not only among the

students, but also lecturers, staff, and third-parties.

The main point of their study was that in order to

become an entrepreneurial university, all parties

must have an entrepreneurial oriented mindset, and

not just the academics. If entrepreneurial intention

and orientation can be combined, the academic

commercialization of the university is guaranteed to

succeed. A similar discovery was made by (Alvarez

et al., 2006) who stated that there is a significant

relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and

entrepreneurial intention which is supported by the

development of good entrepreneurial education

curriculum. Based on this information a hypothesis

can be stated representing the relationship between

Entrepreneurial Orientation and Entrepreneurial

Intention:

H4: Entrepreneurial Orientation has a positive

impact on Entrepreneurial Intention, such that

the higher the degree of Entrepreneurial

Orientation a college student has, the higher

their degree of Entrepreneurial Intention as

well.

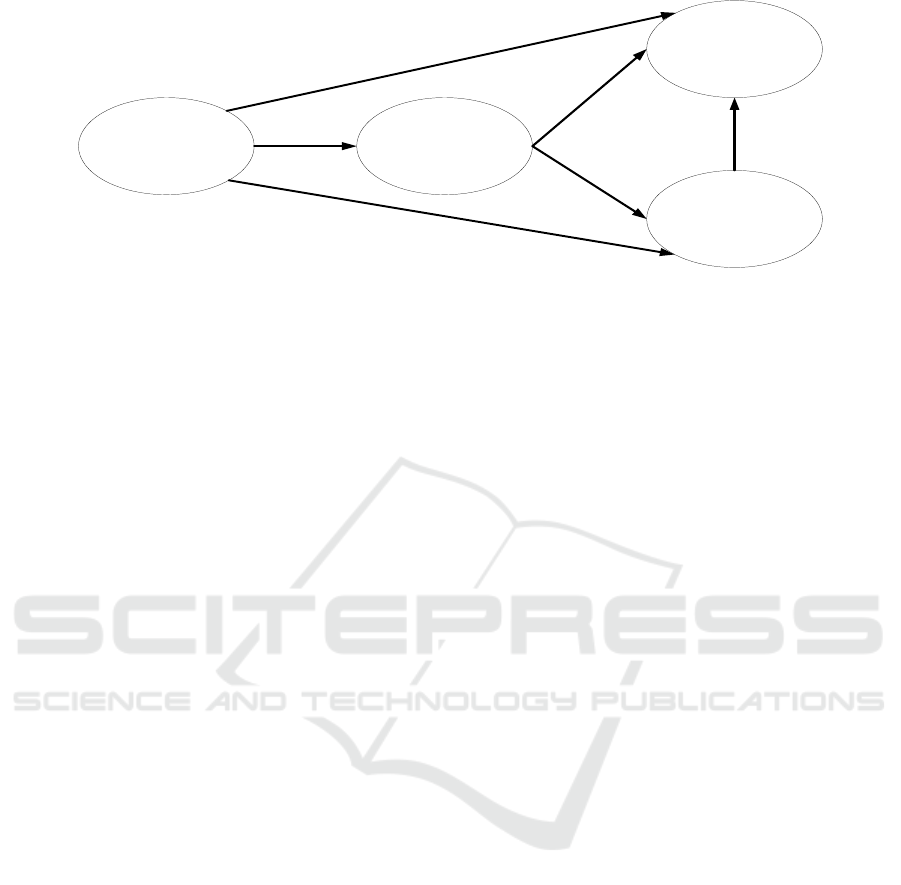

Based on the theories and hypotheses above, a

theoretical frameworks can be created to show the

impact of university business incubator program

quality on entrepreneurial intent and orientation as

shown in Figure 1.

SEABC 2018 - 4th Sriwijaya Economics, Accounting, and Business Conference

312

The Quality of

Incubator Programs

Entrepreneurial

Perceived

Self Control

Entrepreneurial

Intention

Entrepreneurial

Orientation

H1a

H2

H3

H4

H1c

H1b

Figure 1: Theoretical Frameworks

3 METHODS

3.1 Sample and Data Acquisition

This research was conducted using a sample of

college students from 7 universities in Indonesia that

have active Business Incubators. Those targeted

were IIB Darmajaya, UNILA, Universitas Indonesia,

Universitas Padjajaran, Universitas Media

Nusantara, Universitas Bina Nusantara and

Universitas Telkom. The total sample size was 200

students, all of which had joined the

entrepreneurship program from the business

incubator at their university. The program services

from the different incubators varied, but can be

categorized generally into 4: Infrastructure Provider,

Business Services, Financial Provider and People

Connectivity.

3.2 Instrument and Evaluation

The survey instrument was a 10 point Likert

scale ranging from Strongly Disagree to Strongly

Agree. The instrument was distributed online and

had previously undergone a validity and reliability

test. The survey instrument was an expansion of the

previous evaluations performed, namely: The

Quality of Incubator Programs from the work of

Misoska et al. (2016), Entrepreneurial Perceived

Self-Control based on the evaluation of Solesvik

(2013), Entrepreneurial Orientation based on the

evaluation of Song et al. (2017), and Entrepreneurial

Intention from the work of Miranda et al. (2017).

3.3 Analysis

The researchers used Structural Equation

Modeling as the method of analysis and were

assisted by the statistical software AMOS 22.0

which enabled them to test alternative models that

were fairly complex. This analysis with SEM-

AMOS was done in two stages, the first of which

was a measurement test which was followed by a

structural test. The purpose of this analysis was to

determine the impact of The Quality of Incubator

Programs and Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-

Control on Entrepreneurial Orientation and

Entrepreneurial Intentions.

4 RESULTS

The data gathered was analyzed using the

software package SEM IBM-AMOS 22 in order to

test the validity of the model and the relationship

between its variables. Before performing further

analysis, the researchers performed a data

normalizing test to guarantee the quality of the data.

Based on the analysis and normalizing test

performed, the c.r. value for all indicators was

between +2,58 and -2,58 with a multivariate kurtosis

of 3,386 which is well below the cut off value of 8.

All of this indicates that there is no evidence to

suggest that the data has an non normal distribution.

After the model passed the normality test, the

validity and reliability of it was also tested. Table 1

shows the scale indicators with their standardized

estimates and critical ratios in order to evaluate the

validity of the construct for the concepts used in this

research based on the AMOS 22 output from the

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Is The Quality of Business Incubator Programs Capable of Boosting Entrepreneurial Orientation and Intention at Higher Education?

313

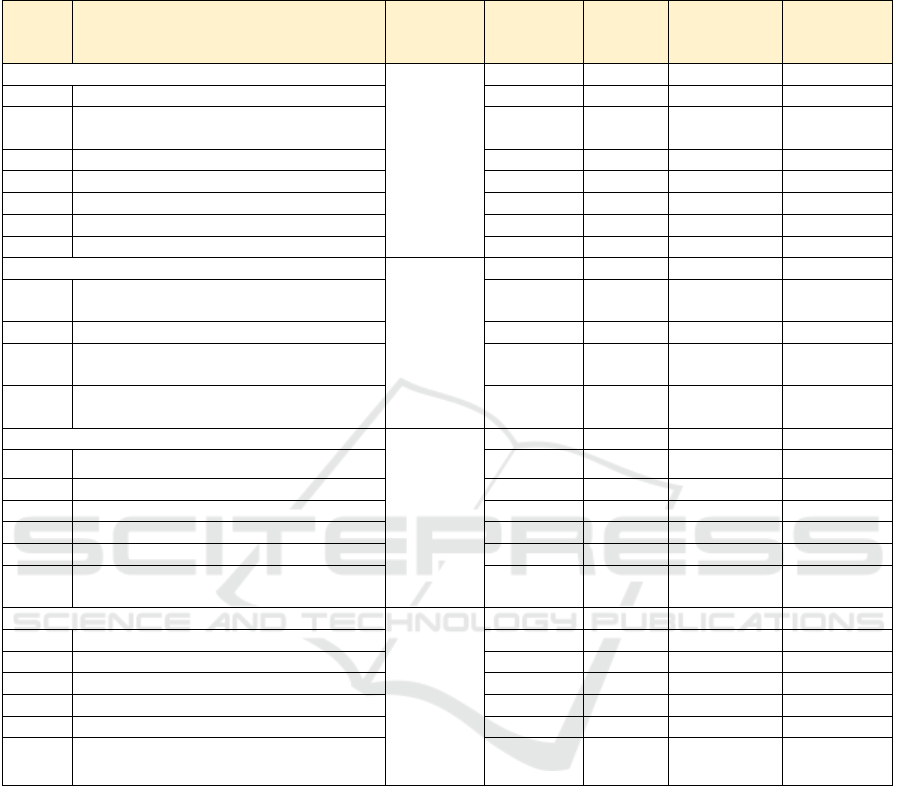

Table 1: Scale, Measurement, Validity, Reability

Code

Scale Indicators

Reference

Std.

Estimate

Critical

Ratio

Convergent

Validity-

Ave

Construct

Reliability

The Quality Of Incubator Programs

Misoska,

Dimitrova

, and

Mrsik

(2016)

0,937

0,990

IPQ1

Better Skill To Conduct Business Plan

0,963

36,403

IPQ2

Thorough Understanding For Business

Risks

0,968

37,768

IPQ3

High Confidence To Develop Business

0,970

38,451

IPQ4

Motivation Toward Achievements

0,969

38,163

IPQ5

Abilities To Harness Incubator Services

0,969

38,009

IPQ6

Easiness To Access Capital Venture

0,971

38,577

IPQ7

Having A Strong Business Network.

0,966

38,577*

Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control

Solesvik

(2013)

0,899

0,973

EPC1

Perceived Of Business Knowledge

Gains.

0,941

28,824*

EPC2

Perceived Easiness To Start A Business

0,950

28,824

EPC3

Perceived Confidant To Handle A

Business Problems.

0,948

28,475

EPC4

Perceived Control Of Choice To

Become Entrepreneur

0,953

29,222

Entrepreneurial Orientation

Song,

Min, Lee,

and Seo

(2017)

0,962

0,993

EO1

Active to Grow & to Innovate

0,986

50,561

EO2

Creative Doing Many Things

0,983

48,329

EO3

Fondness To Have High-Risk Projects

0,980

46,769

EO4

Easy To Make Decisions

0,979

46,126

EO5

First To Take Action.

0,980

46,624

EO6

Always Take Advantage Of New

Opportunities.

0,976

46,624*

Entrepreneurial Intention

Miranda,

Chamorro

-Mera,

and Rubio

(2017).

0,863

0,974

EI1

Entrepreneurship Readiness

0,842

15,430*

EI2

Entrepreneur As Professional Purposes

0,840

15,430

EI3

Committed To Developing Business

0,971

20,448

EI4

Keen To Starting A New Business.

0,974

20,562

EI5

Interest To Develop New Business

0,968

20,305

EI6

Plan To Start A Business After

Graduating.

0,966

20,190

*) This variable was estimated twice: first as a constrained variable and then as an unconstrained variable in order to

calculate the critical ratio.

The Confirmatory Factor Analysis generated a

loading factor for each construct or variable in the

model to show level (acceptable magnitude/value)

which was acceptable, all of which were above 0,60

with a critical ratio above 1,96. As a result, the

indicators give a good reflection of the actual

construct. Additionally, the construct validity

measurements showed good AVE values: The

Quality of Incubator Programs (0,937),

Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control (0,973),

Entrepreneurial Orientation (0,993), and

Entrepreneurial Intention (0,863) all of which were

above the cut-off AVE >= 0,50. Therefore, it can be

concluded that the instrument measuring the four

variables and the indicators are both valid and

reliabel.

The measurements for reliability of the

constructs also showed good results, having the

following values: The Quality of Incubator

Programs (0,990), Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-

Control (0,928), Entreprenuerial Orientation (0,920),

and Entrepreneurial Intention (0,974) which all show

values above the cut-off CRI >= 0,70.

Based on the results of the validity and reliability

studies performed, the model could proceed to the

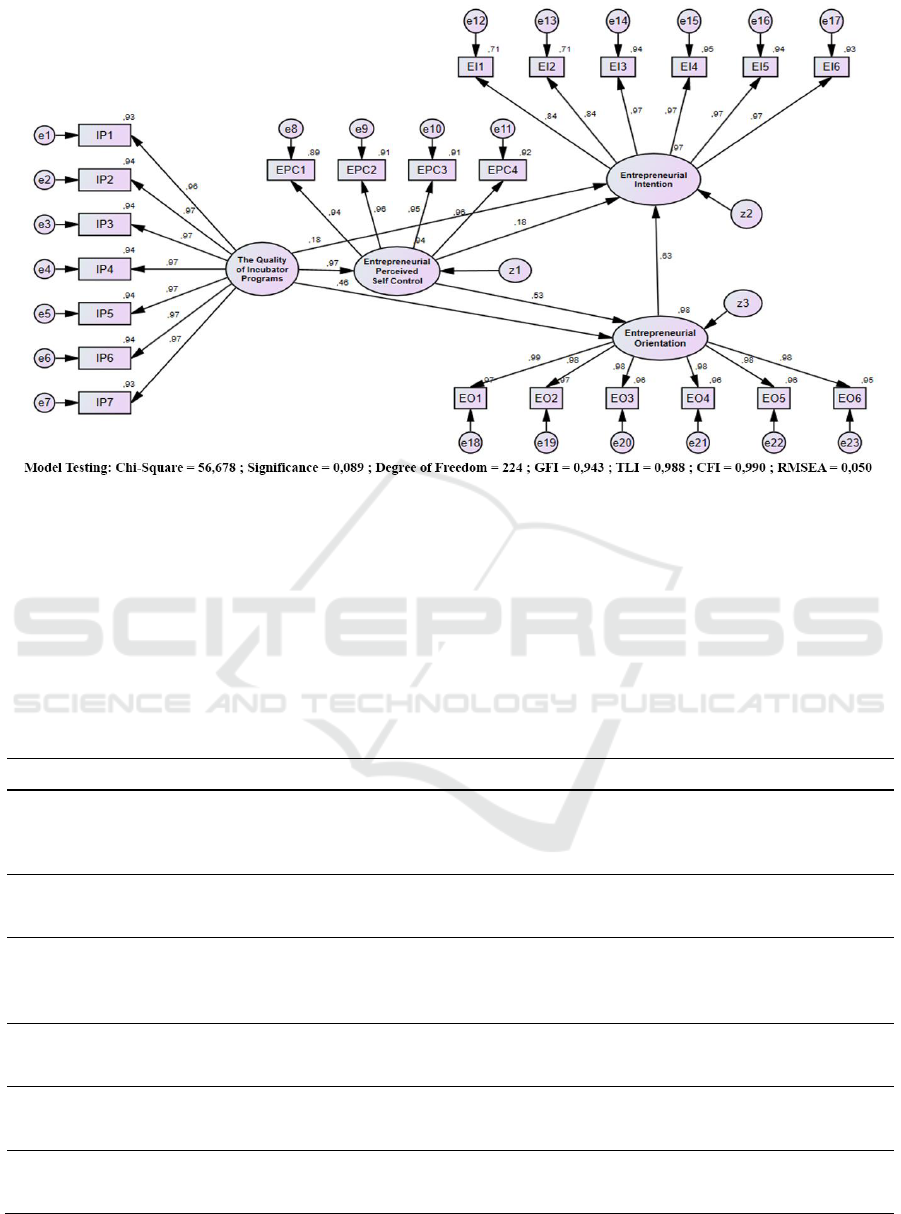

hypothesis testing phase. A diagram of the results

analysis and empirical model testing can be seen in

Figure 2.

SEABC 2018 - 4th Sriwijaya Economics, Accounting, and Business Conference

314

Figure 2: Test Model for Empirical Research

Table 2 displays the results of the structural

equation model analysis. The Goodness of Fit test

was performed using both Statistic and Non-statistic

measurement against the hypothesis and shows that

this model fits the empirical data. This can be seen

through the value of Chi-Square = 56,678 with a

probability of p = 0,089 demonstrating that there is

no difference between the the sample covariance and

the covariance of the estimated population. Further,

the values of GFI (0,943); TLI (0,988); CFI = 0,990

and RMSEA (0,050) fall within the acceptable

range. Therefore, this model is acceptable.

Table 2: The Coefficient of Reggresion

Hyphothesis

Std.estimate

Estimate

Std.error

Critical Ratio

Significance

Conclusion

H1a: The Quality of

Incubator Programs

Entrepreneurial Perceived

Self-Control

0,972

0,893

0,032

27,901

***

Supported

H1b: The Quality of

Incubator Programs

Entrepreneurial Orientation

0,465

0,563

0,095

5,929

***

Supported

H1c: The Quality of

Incubator Programs

Entrepreneurial Intention

0,176

0,136

0,077

1,766

0,077

Not

Supported at

0,05

H2: Entrepreneurial

Perceived Self-Control

Entrepreneurial Orientation

0,53

0,698

0,105

6,672

***

Supported

H3: Entrepreneurial

Perceived Self-Control

Entrepreneurial Intention

0,185

0,156

0,101

1,536

0,125

Rejected

H4: Entrepreneurial

Orientation

Entrepreneurial Intention

0,628

0,402

0,087

4,626

***

Supported

Is The Quality of Business Incubator Programs Capable of Boosting Entrepreneurial Orientation and Intention at Higher Education?

315

From the results of this analysis it can be

observed that hypothesis H1a which states “The

Quality of Incubator Programs has a positive effect

on Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control,” can be

accepted as shown by a critical ratio of 27,901 >

1,96 and a parameter of 0,972. Hypothesis H1b

which state that “The Quality of Incubator Programs

has a positive effect on Entrepreneurial Orientation”

can also be accepted with a critical ratio of 5,929 >

1,96 and a parameter of 0,465. Hypothesis H1c

which states “The Quality of Incubator Programs has

a positive effect on Entrepreneurial Intention” must

be rejected due to a critical ratio of 1,766 < 1,96 and

a parameter of only 0,176 at a significance of 0,05;

however, if we use a significance of 0,1 this

hypothesis can be accepted, albeit with a weak

parameter value.

Hypothesis H2 which states “Entrepreneurial

Perceived Self-Control has a positive effect on

Entrepreneurial Orientation” can be accepted since it

has a critical ratio of 6,672 > 1,96 with a parameter

of 0,53. On the other hand, hypothesis H3 which

states “Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control has a

positive effect on Entrepreneurial Intent” must be

rejected due to a critical ratio of only 1,536 < 1,96

with a weak parameter of 0,185 – for both a 0,05 &

0,10 significance. This means that even university

students with high Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-

Control, do not necessarily desire to become directly

involved in entrepreneurial activities. Finally,

hypothesis H4 which states “Entrepreneurial

Orientation has a positive effect on Entrepreneurial

Intention” can be accepted as it has a critical ratio of

4,626 >1,96 with a parameter of 0,628.

5 DISCUSSION

This research attempts to determine an answer

for the question of whether the programs organized

by the higher education business incubator are able

to boost the entrepreneurial orientation and intention

of college students. Additionally, what is the role of

Entrepreneurial perceived Self-Control on the

entrepreneurial orientation and intention when pre-

exposed to the entrepreneurial programs of a

business incubator. To that end, the researchers have

expanded and explored entrepreneurial orientation

and intention development models with an input of

The Quality of Incubator Programs mediated by

entrepreneurial perceived Self-Control. Based on the

acceptance of the hypotheses and the relationships

between variables, several conclusions can now be

drawn.

One way of growing strong and tenacious

entrepreneurs at the higher education is to give them

assistance and guidance through a variety of

entrepreneurial programs (Ghina, 2014). This means

giving entrepreneurial students guidance over a

period of time by assisting them in education,

training, and internships that are supported by access

to technology, management, marketplaces, capital,

and information. These activities are then used to

provide entrepreneurial skills for tenants so that they

master a variety of areas like marketing and selling

concepts, human resources management, financial

strategy and management, quality control,

networking, etc. (Kadir et al., 2012). With these

skills it is hoped that students have the ability and

self-confidence to both plan and solve business-

related problems. The model and hypothesis testing

performed support this statement, wherein we can

see that there is a significant relationship and large

impact between the quality of incubator programs

and entrepreneurial perceived Self-Control – which

is the degree of self-confidence and perception of

whether someone is or is not able to conduct

entrepreneurial activities.

Entrepreneurial programs are indeed able to

improve one’s skills, but can they directly and

immediately cause students to be interested in doing

business? Many times students get involved in

entrepreneurial programs with a variety of motives.

Some get involved because they are part of an

entrepreneurship class. As a result, they may later

possess business skills, but not necessarily have a

high entrepreneurial intention since they are merely

completing a curriculum requirement. In addition,

there are some students who may join a business

incubator program, but part-way through they lose

interest in the program for a reason related to the

influence of their environment (Sondari, 2014). Such

things were demonstrated in this research model

where The Quality of Incubator Programs only had a

small, insignificant relationship on the

entrepreneurial intention directly.

An interesting discovery was that The Quality of

Incubator Programs and Entrepreneurial Orientation

have a significant relationship. This was made

possible because usually every entrepreneurial

program is designed to stimulate students to think

creatively and innovatively, work proactively, and

take risks. Not only that, Entrepreneurial Perceived

Self-Control was shown to have a great mediating

effect on The Quality of Incubator Programs and

Entrepreneurial Orientation. This strengthens the

research results of Montiel Campos (2017), who

state that if entrepreneurs have energy, self-

SEABC 2018 - 4th Sriwijaya Economics, Accounting, and Business Conference

316

confidence, and skills mastery, they tend to be able

to involve themselves in finding new opportunities,

growing the marketplace, and even optimizing

organizational processes to be better adapted to the

times.

Another conclusion that can be identified from

the research are that there is no significant

relationship between Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-

Control and Entrepreneurial Intention in the model.

However, when Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-

Control is first paired with Entrepreneurial

Orientation the result will be a significant

relationship and a strong impact on Entrepreneurial

Intention. This demonstrates that it is not easy for

higher education business incubators to generate

entrepreneurial intention. Rather the business

incubator must first stimulate the students mindset to

have an Entreprenuerial Orientation in order to

increase their entrepreneurial intention.

6 CONCLUSION & FUTURE

RESEARCH

The implications of this research are that there is

an empirical model that demonstrates the formation

of entrepreneurial orientation and intention.

Business incubator programs—in the form of quality

services like Infrastructures Provider, Business

Services, Financial Provider and People

Connectivity—can cause an entrepreneurial student

to gain a variety of business skills that will give

him/her self-confidence and a positive perception in

doing business. Later this self-confidence and

positive perception can shape students who have an

entrepreneurial orientation – being innovative and

proactive as well as taking risk—to the extent that it

can increase their entrepreneurial intention.

Therefore, what needs to be emphasized is the

importance of business incubators ensuring that their

programs are capable of increasing entrepreneurial

orientation, as this variable is the key to improving

the entrepreneurial intention among university

students.

A study of The Quality of Incubator Programs

related to Entrepreneurial Perceived Self-Control is

a new initiative to help explain Entrepreneurial

Orientation and Intention. This study was

structurally prepared and scientifically performed,

however, a few limitations must be addressed for

further research. Firstly, the ontology of Quality of

Incubator Programs and Entrepreneurial Perceived

Self-Control has been clearly defined as a concept,

but efforts to develop the dimensions of this concept

are still very open, especially the expansion of the

indicators. It is also possible that they could be

retested not only among university students.

Additionally, there are some insignificant

relationships in the model related to the formation of

Entreprenuerial Intention, such that these could be

explored further to find the causes or antecedents

that have a stronger relationship.

REFERENCES

Adom, K. & Asare-Yeboa, I. T. 2016. An evaluation of

human capital theory and female entrepreneurship in

sub-Sahara Africa: Some evidence from Ghana.

International Journal of Gender and

Entrepreneurship, 8, 402-423.

Aerts, K., Matthyssens, P. & Vandenbempt, K. 2007.

Critical role and screening practices of European

business incubators. Technovation, 27, 254-267.

Ajzen, I. 1991. The theory of planned behavior.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 50, 179-211.

Alvarez, R. D., Denoble, A. F. & Jung, D. 2006.

Educational Curricula and Self-Efficacy:

Entrepreneurial Orientation and New Venture

Intentions among University Students in Mexico. 5,

379-403.

Blackburne, G. D. & Buckley, P. J. 2017. The

international business incubator as a foreign market

entry mode. Long Range Planning.

De Jorge‐Moreno, J., Laborda Castillo, L. & Sanz

Triguero, M. 2012. The effect of business and

economics education programs on students'

entrepreneurial intention. European Journal of

Training and Development, 36, 409-425.

Ferrandiz, J., Fidel, P. & Conchado, A. 2018. Promoting

entrepreneurial intention through a higher education

program integrated in an entrepreneurship ecosystem.

International Journal of Innovation Science, 10, 6-21.

Ghina, A. 2014. Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship

Education in Higher Education Institutions. Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 115, 332-345.

Herman, E. & Stefanescu, D. 2017. Can higher education

stimulate entrepreneurial intentions among

engineering and business students? Educational

Studies, 43, 312-327.

Hong, J., Yang, Y., Wang, H., Zhou, Y. & Deng, P. 2018.

Incubator interdependence and incubation

performance in China’s transition economy: the

moderating roles of incubator ownership and strategy.

Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 1-15.

Ismail, K., Anuar, M. A., Omar, W. Z. W., Aziz, A. A.,

Seohod, K. & Akhtar, C. S. 2015. Entrepreneurial

Intention, Entrepreneurial Orientation of Faculty and

Students towards Commercialization. Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 181, 349-355.

Is The Quality of Business Incubator Programs Capable of Boosting Entrepreneurial Orientation and Intention at Higher Education?

317

Kadir, M. B. A., Salim, M. & Kamarudin, H. 2012. The

Relationship Between Educational Support and

Entrepreneurial Intentions in Malaysian Higher

Learning Institution. Procedia - Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 69, 2164-2173.

Kamal, S. B. M., Zawawi, D. & Abdullah, D. 2016.

Entrepreneurial Orientation for Small and Medium

Travel Agencies in Malaysia. Procedia Economics

and Finance, 37, 115-120.

Krueger, N., Hansen, D. J., Michl, T. & Welsh, D. H. B.

2011. Thinking “Sustainably”: The Role of Intentions,

Cognitions, and Emotions in Understanding New

Domains of Entrepreneurship. 13, 275-309.

Krueger, N. F. & Carsrud, A. L. 1993. Entrepreneurial

intentions: Applying the theory of planned behaviour.

Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 5, 315-

330.

Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D. & Carsrud, A. L. 2000.

Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions.

Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 411-432.

Li, L., Jiang, F., Pei, Y. & Jiang, N. 2017. Entrepreneurial

orientation and strategic alliance success: The

contingency role of relational factors. Journal of

Business Research, 72, 46-56.

Marques, C. S. E., Santos, G., Galvão, A., Mascarenhas,

C. & Justino, E. 2018. Entrepreneurship education,

gender and family background as antecedents on the

entrepreneurial orientation of university students.

International Journal of Innovation Science, 10, 58-

70.

Mei, H., Zhan, Z., Fong, P. S. W., Liang, T. & Ma, Z.

2015. Planned behaviour of tourism students’

entrepreneurial intentions in China. Applied

Economics, 48, 1240-1254.

Miranda, F. J., Chamorro-Mera, A. & Rubio, S. 2017.

Academic entrepreneurship in Spanish universities:

An analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurial

intention. European Research on Management and

Business Economics, 23, 113-122.

Misoska, A. T., Dimitrova, M. & Mrsik, J. 2016. Drivers

of entrepreneurial intentions among business students

in Macedonia. Economic Research-Ekonomska

Istraživanja, 29, 1062-1074.

Montiel Campos, H. 2017. Impact of entrepreneurial

passion on entrepreneurial orientation with the

mediating role of entrepreneurial alertness for

technology-based firms in Mexico. Journal of Small

Business and Enterprise Development, 24, 353-374.

Morgan, H. 2014. Venture Capital Firms and Incubators.

Research-Technology Management, 57, 40-45.

Murphy, P. J., Welsch, H. P. & Liao, J. 2006. A

conceptual history of entrepreneurial thought. Journal

of Management History, 12, 12-35.

Murugesan, R. & Jayavelu, R. 2015. Testing the impact of

entrepreneurship education on business, engineering

and arts and science students using the theory of

planned behaviour. Journal of Entrepreneurship in

Emerging Economies, 7, 256-275.

Nabi, G., Holden, R. & Walmsley, A. 2010.

Entrepreneurial intentions among students: towards a

re‐focused research agenda. Journal of Small Business

and Enterprise Development, 17, 537-551.

Poole, D. L. 2018. Entrepreneurs, entrepreneurship and

SMEs in developing economies: How subverting

terminology sustains flawed policy. World

Development Perspectives, 9, 35-42.

Randerson, K. 2016. Entrepreneurial Orientation: do we

actually know as much as we think we do?

Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 28, 580-

600.

Rodrigo-Alarcón, J., García-Villaverde, P. M., Ruiz-

Ortega, M. J. & Parra-Requena, G. 2018. From social

capital to entrepreneurial orientation: The mediating

role of dynamic capabilities. European Management

Journal, 36, 195-209.

Solesvik, M. Z. 2013. Entrepreneurial motivations and

intentions: investigating the role of education major.

Education + Training, 55, 253-271.

Sondari, M. C. 2014. Is Entrepreneurship Education

Really Needed?: Examining the Antecedent of

Entrepreneurial Career Intention. Procedia - Social

and Behavioral Sciences, 115, 44-53.

Song, G., Min, S., Lee, S. & Seo, Y. 2017. The effects of

network reliance on opportunity recognition: A

moderated mediation model of knowledge acquisition

and entrepreneurial orientation. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change, 117, 98-107.

Usaci, D. 2015. Predictors of Professional Entrepreneurial

Intention and Behavior in the Educational Field.

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 187, 178-

183.

Van Weele, M., Van Rijnsoever, F. J. & Nauta, F. 2017.

You can't always get what you want: How

entrepreneur's perceived resource needs affect the

incubator's assertiveness. Technovation, 59, 18-33.

Viinikainen, J., Heineck, G., Böckerman, P., Hintsanen,

M., Raitakari, O. & Pehkonen, J. 2017. Born

entrepreneurs? Adolescents’ personality characteristics

and entrepreneurship in adulthood. Journal of

Business Venturing Insights, 8, 9-12.

Woodside, A. G., Bernal, P. M. & Coduras, A. 2016. The

general theory of culture, entrepreneurship,

innovation, and quality-of-life: Comparing nurturing

versus thwarting enterprise start-ups in BRIC,

Denmark, Germany, and the United States. Industrial

Marketing Management, 53, 136-159.

Wright, F. 2017. How do entrepreneurs obtain financing?

An evaluation of available options and how they fit

into the current entrepreneurial ecosystem. Journal of

Business & Finance Librarianship, 22, 190-200.

SEABC 2018 - 4th Sriwijaya Economics, Accounting, and Business Conference

318