Is an Educational Level Affect Women’s Participation on Cervical

Cancer Screening?

A Systematic Review

Rafika Rosyda

1

, Budi Santoso

2

, Esti Yunitasari

1

1

Faculty of Nursing Universitas Airlangga, Kampus C Mulyorejo, Surabaya, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya

Keyword: Cervical cancer, Cervical cancer prevention, Screening, Early detection, Education.

Abstract: Cervical cancer became fourth most common cancer case among women in the world. There were

approximately 528.000 new cases in 2012. Screening is the most proven method to prevent cervical cancer.

Level of education seems to be an important predictor of cancer screening participation. Nowadays, there is

a little strong evidence of this specific association. Therefore, a systematic review is necessary. This review

was guided by PICO framework to identified appropriate resources for relevant study. Search of the studies

were carried out by Pro-Quest and Medline, with keywords: “cervical cancer screening”, “Pap smear”,

“VIA” “screening program”, “socioeconomic factors”, “educational level” and “screening participation”.

From 904 studies found, 13 included for review. 11 of 13 (84,6%) reported that level of education were

positively associated with women’s participation on cervical cancer screening, and only 2 studies reported

that there is no association. This review conclude that women with higher educational level are more likely

to participate cervical cancer screening.

1 BACKGROUND

Cervical cancer became fourth most common cancer

among women and seventh in all cancer all over the

world. There were approximately 528.000 new cases

in 2012. In Western counties, cervical cancer

prevention effort was done by increasing HPV

vaccination (Cullen, Stokley, & Markowitz, 2014).

However, screening is the most proven method for

reducing rates of cervical cancer (de Blasio, Neilson,

Klemp, & Skjeldestad, 2012). There were some

evidences that Pap Smear, and VIA are associated

with decreasing mortality of cervical cancer

(Meggiolaro et al., 2016; Sankaranarayanan et al.,

2007).

There are some recommendations for cervical

cancer screening (Schwaiger, Aruda, LaCoursiere,

Lynch, & Rubin, 2013). In general, cervical

screening interval may once in 3 to 5 years

(Schwaiger et al., 2013). Screening policy could

affect screening participation. Other than that, there

are more various factors as well as the characteristic

of health system, sociocultural factors,

environmental factors, invitation method, and

individual factors such as age, occupation, and

education. Notably, level of education is one of

health determinant that could be an important

predictor of cancer screening participation (Damiani

et al., 2012).

Although there were a lot of studies had found

positive relationship between level of education and

participation on cervical cancer screening, some of

the results did not find statistically significant.

Nowadays, the strong evidence for this relationship

is still low. Therefore, this systematic review is

necessary. This systematic review assessed the

impact of educational level on women’s

participation on cervical cancer screening.

2 METHODS

The PICO framework was used to guide this

systematic review, with P: sexually active women,

with no symptom and history of female cancers, I:

higher level of education, C: lower level of

education, O: have ever done cervical cancer

screening in their lifetime.

482

Rosyda, R., Santoso, B. and Yunitasari, E.

Is an Educational Level Affect Women’s Participation on Cervical Cancer Screening?.

DOI: 10.5220/0008327204820488

In Proceedings of the 9th International Nursing Conference (INC 2018), pages 482-488

ISBN: 978-989-758-336-0

Copyright

c

2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2.1 Search Strategy

Search of the studies were carried out by ProQuest

and Medline, with keywords: “cervical cancer

screening”, “Pap smear”, “VIA” “screening

program”, “socioeconomic factors”, “educational

level” and “screening participation”.

2.2 Assessment of the Studies

2.2.1 Eligibility

The inclusion criteria for this review:

- Studies published between 2008 – 2018,

- Articles published in English,

- The result section reported the relationship

between level of education and cervical cancer

screening participation.

The exclusion criteria for this review:

- Participants were women with history or family

history of cervical cancer,

- Participants with other disease (e.g. diabetes).

Methodological Quality:

The quality assessment consisted:

- The design of the study,

- Data collection,

- Selected bias,

- Statistical analysis conformity.

Quality assessment was done by rating each item

above as “strong”, “moderate”, or “weak”. As

consequence, the study would be “high quality” if

three of them were strong, with no weak. If there

was only one weak, study would be “moderate

quality”, and if there were more than one item rated

weak, the study would be “low quality”.

2.2.2 Data Extraction

These following items were collected from each

study:

- Author, years of publication

- Design of the study

- Population size and targeted age

- Outcome

- Educational level

- Relationship between educational level and

screening participation

3 RESULTS

3.1 Included Studies

Twelve from Thirteen studies are cross sectional,

and one is case control. Studies selected for this

review obtained by the Swedish National Cervical

Screening Registry (Broberg et al., 2018),

Morehouse School of Medicine (Miles-Richardson,

Allen, Claridy, Booker, & Gerbi, 2017), The

KNHNES (Chang et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2013),

WHO’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health

(Akinyemiju, Ogunsina, Sakhuja, Ogbhodo, &

Braithwaite, 2016), GPMSSP (Gyulai et al., 2015),

University of Pittsburgh (Alfaro et al., 2015),

Karolinska Institutet (Östensson et al., 2015), New

Americans Community Services, and University of

Minnesota (Harcourt et al., 2014), European Health

Interview Survey for Spain (Martín-López et al.,

2012), ISTAT (Damiani et al., 2012), BRFSS and

ARF (Coughlin, Leadbetter, Richards, & Sabatino,

2008), and the JCUSH (Blackwell, Martinez, &

Gentleman, 2008).

Two studies were conducted in Sweden (Broberg

et al., 2018; Östensson et al., 2015), four studies in

US (Blackwell et al., 2008; Coughlin et al., 2008;

Harcourt et al., 2014; Miles-Richardson et al., 2017),

two studies in Korea (Chang et al., 2017; Lee et al.,

2013), and the other respectively in Canada

(Blackwell et al., 2008), El Salvador (Alfaro et al.,

2015), Spain (Martín-López et al., 2012), Italy

(Damiani et al., 2012), Hungary (Gyulai et al.,

2015). Twenty two different populations were

identified. Specifically, 10 studies analyzed one

population, and 3 studies analyzed more.

3.2 Quality Assessment

Based on the design of the study, twelve studies

rated “weak” due to cross sectional, and one study

rated “moderate” due to case control. Based on their

data collection, all studies rated “moderate” because

obtained by surveys. Based on selection bias, ten

studies rated “strong” (Akinyemiju et al., 2016;

Blackwell et al., 2008; Broberg et al., 2018; Chang

et al., 2017; Coughlin et al., 2008; Damiani et al.,

2012; Gyulai et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2013; Martín-

López et al., 2012; Miles-Richardson et al., 2017)

because conducted nationwide and enrolled

representative sample. Then, based on statistical

analysis conformity, all studies rated “strong”.

Overall, all studies are in moderate quality.

Is an Educational Level Affect Women’s Participation on Cervical Cancer Screening?

483

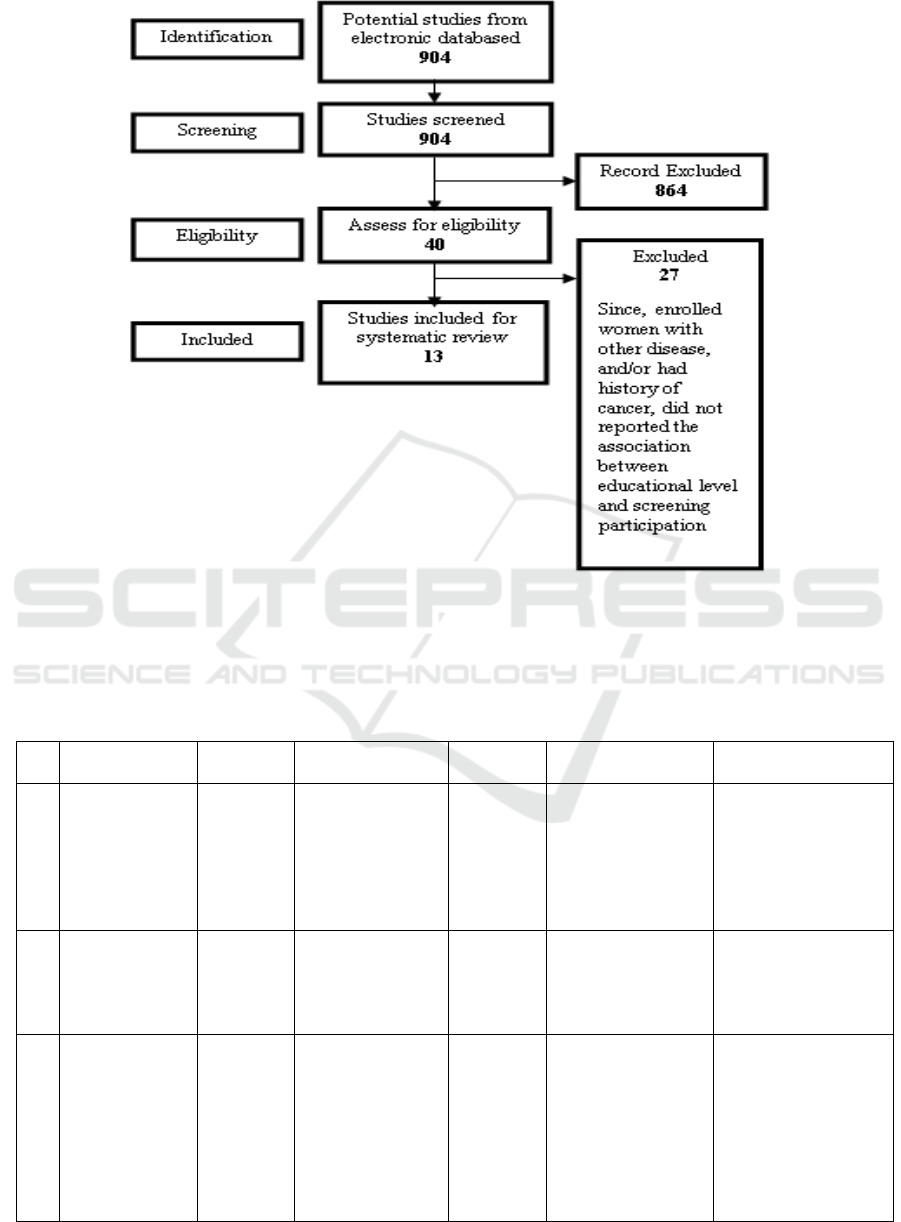

Figure 1: Review method.

3.3 Study Characteristic

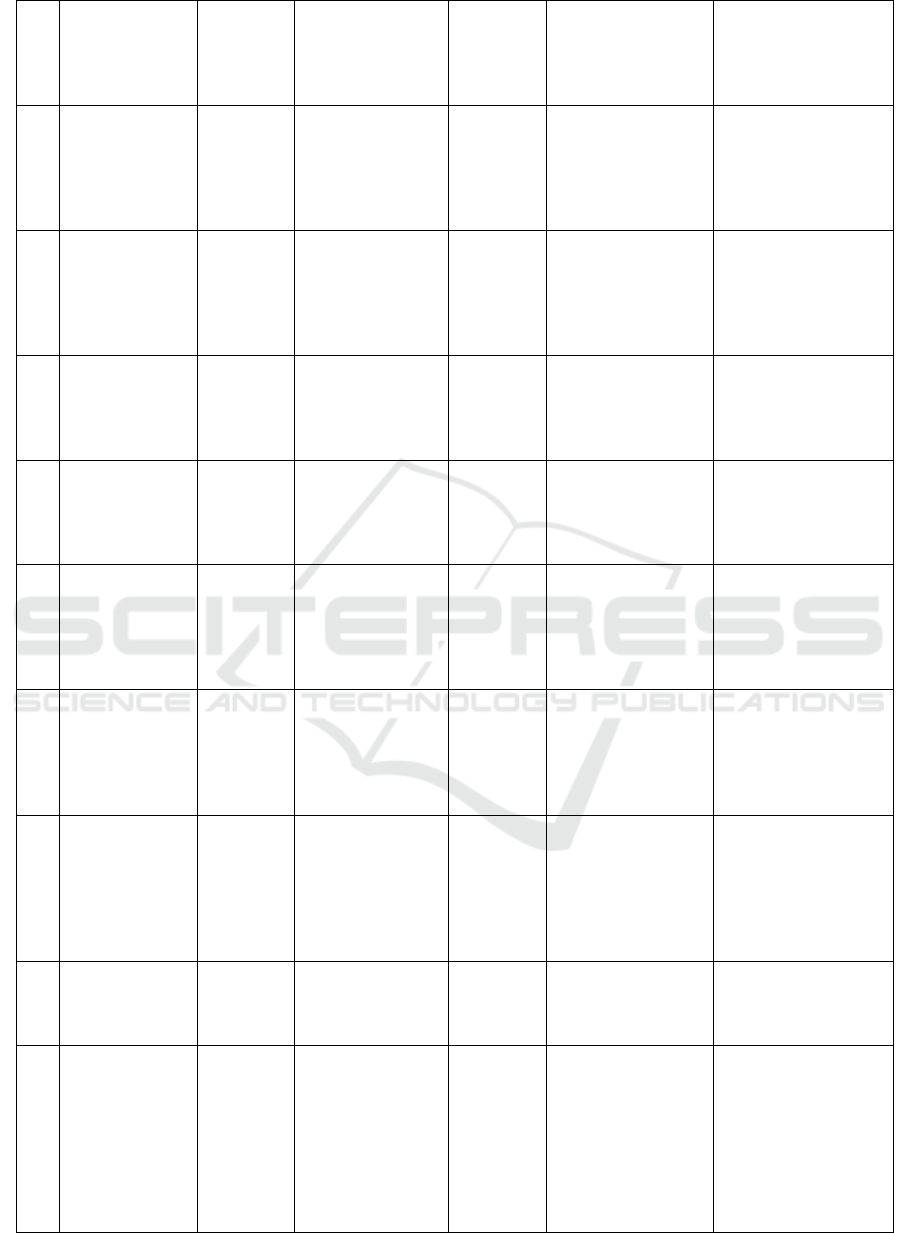

Table 1: Study Characteristic.

N

o

Author, Year of

Publication

Design

Populations,

Targeted Age

Outcome

Educational Level

Relationship

1

(Broberg et al.,

2018)

Case

control

1

Sweden;

Case; n=314.302

Control;

n=266.706

30-60 years old

Attended

pap smear

test

1. ≤ 9 years

2. 10-12 years

3. > 12 years

Women with lower

education were more

likely to not attend

cervical screening

2

(Chang et al.,

2017)

Cross

sectional

1

Korea; n=3.734

15-39 years old

Had pap

smear test

1. < 6 years

2. 6-9 years

3. 10-12 years

4. >12 years

Higher educational

levels associated with

participation in

cervical cancer

screening

3

(Akinyemiju et

al., 2016)

Cross

sectional

5

China; n=8.002

India; n=7.489

Mexico; 1.689

Russia; n=2.676

South Africa;

n=2.427

21-65 years old

Had pap

smear test

1. No formal

education

2. Primary

3. Secondary

4. University/

college

education,

significantly

increased cervical

cancer screening

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

484

4

(Alfaro et al.,

2015)

Cross

sectional

1

El Salvador;

n=409

30-49 years old

Had

cervical

cancer

screening

1. < Elementary

2. Middle school

3. > High school

There was no

association

between screening

participation and

educational level

5

(Östensson et

al., 2015)

Cross

sectional

1

Sweden; n=1.510

23-60 years old

Attended

cervical

cancer

screening

1. < High-school

2. High-school or

equal

3. > High-school

Educational levels

positively associated

with cervical cancer

screening

participation

6

(Harcourt et al.,

2014)

Cross

sectional

1

USA; n=421

≥ 18 years old

Had

cervical

cancer

screening

1. ≤ High school

2. > High school

There was no

association between

educational level and

cervical cancer

screening

participation

7

(Martín-López

et al., 2012)

Cross

sectional

1

Spain; n=7.634

25-64 years old

Had Pap

smear test

1. Primary

2. Secondary

3. University

Undergoing cervical

cancer screening

positively associated

with higher

educational levels

8

(Damiani et al.,

2012)

Cross

sectional

1

Italy; n=35.349

25-64 years old

Had 1 pap

smear test

1. < Primary

2. Secondary

3. > high-school

Education level were

positively associated

with attendance to

cervical cancer

screening

9

(Coughlin et

al., 2008)

Cross

sectional

1

USA; n=97.820

≥18 years old

Had Pap

smear test

1. < high-school

2. High-school

graduate/ GED

3. Some college/

technical school

4. College graduate

higher educational

levels related to

having cervical

cancer screening

10

(Blackwell et

al., 2008)

Cross

sectional

2

Canada; n=1.895

US; n=2.959

18-69 years old

Had Pap

smear test

1. < High-school

2. High-school

Diploma/ GED

3. Vocational

certificate

4. University

Educational levels

predict compliance

with cervical cancer

screening in Canada

(and nearly

did in the US)

11

(Gyulai et al.,

2015)

Cross

sectional

1

Hungary; n=

1539

25-65 years old

Had pap

smear test

1. Primary

2. Some Secondary

3. Secondary

4. Post-secondary

without diploma

5. College /

university

higher education

increases

participation

12

(Miles-

Richardson et

al., 2017)

Cross

sectional

1

USA; n=272.692

≥ 18 years old

Had pap

smear test

1. ≤ high school

2. Some college

3. College graduate

women with higher

level of education

were more likely to

be screened

13

(Lee et al.,

2013)

Cross

sectional

5

Korea; N=17.105

[1998]; n=2725

[2001]; n=1622

[2005]; n=2596

[2008]; n=2944

[2010]; n=2737

≥30 years old

Participat

ed

cervical

cancer

screening

1. ≤ elementary

2. Middle – high

school

3. ≥ university

Educational levels

influenced screening

participation. lower

educational levels

were less likely to be

screened

Is an Educational Level Affect Women’s Participation on Cervical Cancer Screening?

485

4 DISCUSSION

This review found that 84,6% studies reported that

women with higher level of education are more

likely to participate cervical cancer screening

compare with women with lower level of education.

Overall, this review confirms that the risk of

participating cervical cancer screening is affected by

education.

Similar review found that there was positive

association between educational level and some

health-related behavior, one of them is screening

participation (Cutler & Lleras-Muney, 2010). The

reason is Well-educated women may have better

interest, and better access to resources and

information, so they have better knowledge about

health issue and behavior to improve their health.

Also, they have greater awareness of risks (Adams,

2010; Hahn & Truman, 2015). Simply, sufficiency

of current knowledge has a positive influence on

health-promoting behavioral options.

The argument of this finding is health literacy

has positive association with level of education.

Health literacy is an individual capacity to get,

process, and figure out the necessary information

and basic health service to determine health-related

decisions. One of the important factor that can

determine health literacy is level of education.

People with higher educational level were found to

demonstrated higher health literacy skill. (van der

Heide et al., 2013). Well-educated people are more

likely to completely understand the information and

instructions. Furthermore, people with higher level

of health literacy can increase the likelihood of

communication to health care providers that can lead

to better outcomes. Simply, low health literacy skill

can be a barrier in access health information, health

service, and disease prevention.

People with high capacity of health literacy also

have a higher capacity to be informed that screening

is necessary to prevent cervical cancer. This means

that the association between educational level and

some health behaviors – in this case cervical cancer

screening participation – is affected by health

literacy skill.

Cervical cancer screening participation is also

affected by the type of health care system and its

accessibility, screening policy, environmental,

sociocultural, and factors at individual level such as

age, race, insurance coverage and occupation

(Blackwell et al., 2008; Coughlin et al., 2008;

Damiani et al., 2012). In addition, cultural factors

can predict cervical cancer screening participation

and may be related with educational level. Some

studies reported that low cervical cancer screening

participation was caused by low knowledge about

screening guideline, along with various cultural

factors, such as negative attitudes toward illness and

misunderstanding about risk factors and screening

practices (Cadet, Burke, Stewart, Howard, &

Schonberg, 2017; Luque et al., 2015; Madhivanan,

Valderrama, Krupp, & Ibanez, 2016). Furthermore,

there is a correlation between cervical cancer

screening and some of the health-related behaviors,

including unhealthy diet, obesity, lack of physical

activity, and tobacco and alcohol consumption

(Damiani et al., 2012; Martín-López et al., 2012).

All factors above should be considered as they

may lead to be confounders in the evaluation of the

role of education level on cervical cancer screening

participation. Nevertheless, all included studies

conformed their analysis to those possible

confounding factors.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Women with higher educational level have a higher

risk to participate cervical cancer screening. This

finding can be considered in decision-making

processes to reduce the inequalities and increase

women’s participation on cervical cancer screening.

Overall, this review confirms that more educated

women are more likely to have cervical cancer

screening.

REFERENCES

Adams, R. J. (2010). Improving health outcomes with

better patient understanding and education. Risk

Management and Healthcare Policy, 3(3), 61–72.

https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S7500

Akinyemiju, T., Ogunsina, K., Sakhuja, S., Ogbhodo, V.,

& Braithwaite, D. (2016). Life-course socioeconomic

status and breast and cervical cancer screening:

analysis of the WHO’s Study on Global Ageing and

Adult Health (SAGE). BMJ Open, 6(11), e012753.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012753

Alfaro, K. M., Gage, J. C., Rosenbaum, A. J., Ditzian, L.

R., Maza, M., Scarinci, I. C., … Cremer, M. L. (2015).

Factors affecting attendance to cervical cancer

screening among women in the Paracentral Region of

El Salvador: a nested study within the CAPE HPV

screening program. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1058.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2360-7

Blackwell, D. L., Martinez, M. E., & Gentleman, J. F.

(2008). Women’s compliance with public health

guidelines for mammograms and pap tests in Canada

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

486

and the United States: an analysis of data from the

Joint Canada/United States Survey Of Health.

Women’s Health Issues : Official Publication of the

Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 18(2), 85–99.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2007.10.006

Broberg, G., Wang, J., Östberg, A.-L., Adolfsson, A.,

Nemes, S., Sparén, P., & Strander, B. (2018). Socio-

economic and demographic determinants affecting

participation in the Swedish cervical screening

program: A population-based case-control study.

PLOS ONE, 13(1), e0190171.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190171

Cadet, T. J., Burke, S. L., Stewart, K., Howard, T., &

Schonberg, M. (2017). Cultural and emotional

determinants of cervical cancer screening among older

Hispanic women. Health Care for Women

International, 38(12), 1289–1312.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2017.1364740

Chang, H. K., Myong, J.-P., Byun, S. W., Lee, S.-J., Lee,

Y. S., Lee, H.-N., … Park, T. C. (2017). Factors

associated with participation in cervical cancer

screening among young Koreans: a nationwide cross-

sectional study. BMJ Open, 7(4), e013868.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013868

Coughlin, S. S., Leadbetter, S., Richards, T., & Sabatino,

S. A. (2008). Contextual analysis of breast and

cervical cancer screening and factors associated with

health care access among United States women, 2002.

Social Science & Medicine, 66(2), 260–275.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.09.009

Cullen, K. A., Stokley, S., & Markowitz, L. E. (2014).

Uptake of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Among

Adolescent Males and Females: Immunization

Information System Sentinel Sites, 2009–2012.

Academic Pediatrics, 14(5), 497–504.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2014.03.005

Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2010). Understanding

differences in health behaviors by education. Journal

of Health Economics, 29(1), 1–28.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.10.003

Damiani, G., Federico, B., Basso, D., Ronconi, A.,

Bianchi, C. B. N. A., Anzellotti, G. M., … Ricciardi,

W. (2012). Socioeconomic disparities in the uptake of

breast and cervical cancer screening in Italy: a cross

sectional study. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 99.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-99

de Blasio, B. F., Neilson, A. R., Klemp, M., &

Skjeldestad, F. E. (2012). Modeling the impact of

screening policy and screening compliance on

incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in the post-

HPV vaccination era. Journal of Public Health, 34(4),

539–547. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds040

Gyulai, A., Nagy, A., Pataki, V., Tonté, D., Ádány, R., &

Vokó, Z. (2015). Survey of Participation in Organised

Cervical Cancer-Screening Programme in Hungary.

Central European Journal of Public Health, 23(4),

360–364. https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a4068

Hahn, R. A., & Truman, B. I. (2015). Education Improves

Public Health and Promotes Health Equity.

International Journal of Health Services, 45(4), 657–

678. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731415585986

Harcourt, N., Ghebre, R. G., Whembolua, G.-L., Zhang,

Y., Warfa Osman, S., & Okuyemi, K. S. (2014).

Factors Associated with Breast and Cervical Cancer

Screening Behavior Among African Immigrant

Women in Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant and

Minority Health, 16(3), 450–456.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9766-4

Lee, M., Park, E.-C., Chang, H.-S., Kwon, J. A., Yoo, K.

B., & Kim, T. H. (2013). Socioeconomic disparity in

cervical cancer screening among Korean women:

1998–2010. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 553.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-553

Luque, J. S., Tarasenko, Y. N., Maupin, J. N., Alfonso, M.

L., Watson, L. C., Reyes-Garcia, C., & Ferris, D. G.

(2015). Cultural Beliefs and Understandings of

Cervical Cancer Among Mexican Immigrant Women

in Southeast Georgia. Journal of Immigrant and

Minority Health, 17(3), 713–721.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0117-5

Madhivanan, P., Valderrama, D., Krupp, K., & Ibanez, G.

(2016). Family and cultural influences on cervical

cancer screening among immigrant Latinas in Miami-

Dade County, USA. Culture, Health & Sexuality,

18(6), 710–722.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2015.1116125

Martín-López, R., Hernández-Barrera, V., de Andres, A.

L., Carrasco-Garrido, P., de Miguel, A. G., &

Jimenez-Garcia, R. (2012). Trend in cervical cancer

screening in Spain (2003–2009) and predictors of

adherence. European Journal of Cancer Prevention,

21(1), 82–88.

https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32834a7e46

Meggiolaro, A., Unim, B., Semyonov, L., Miccoli, S.,

Maffongelli, E., & La Torre, G. (2016). The role of

Pap test screening against cervical cancer: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. La Clinica Terapeutica,

167(4), 124–139.

https://doi.org/10.7417/CT.2016.1942

Miles-Richardson, S., Allen, S., Claridy, M. D., Booker,

E. A., & Gerbi, G. (2017). Factors Associated with

Self-Reported Cervical Cancer Screening Among

Women Aged 18 Years and Older in the United States.

Journal of Community Health, 42(1), 72–77.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0231-5

Östensson, E., Alder, S., Elfström, K. M., Sundström, K.,

Zethraeus, N., Arbyn, M., & Andersson, S. (2015).

Barriers to and Facilitators of Compliance with Clinic-

Based Cervical Cancer Screening: Population-Based

Cohort Study of Women Aged 23-60 Years. PLOS

ONE, 10(5), e0128270.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128270

Sankaranarayanan, R., Esmy, P. O., Rajkumar, R.,

Muwonge, R., Swaminathan, R., Shanthakumari, S.,

… Cherian, J. (2007). Effect of visual screening on

cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Tamil

Nadu, India: a cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet,

370(9585), 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-

6736(07)61195-7

Schwaiger, C. B., Aruda, M. M., LaCoursiere, S., Lynch,

Is an Educational Level Affect Women’s Participation on Cervical Cancer Screening?

487

K. E., & Rubin, R. J. (2013). Increasing Adherence to

Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines. The Journal

for Nurse Practitioners, 9(8), 528–535.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2013.05.013

van der Heide, I., Wang, J., Droomers, M.,

Spreeuwenberg, P., Rademakers, J., & Uiters, E.

(2013). The Relationship Between Health, Education,

and Health Literacy: Results From the Dutch Adult

Literacy and Life Skills Survey. Journal of Health

Communication, 18(sup1), 172–184.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.825668

INC 2018 - The 9th International Nursing Conference: Nurses at The Forefront Transforming Care, Science and Research

488