A Retrospective Study: Acne Vulgaris with Oral Antibiotic

Treatment at Dermatovenereology Outpatient Clinic Dr. Soetomo

General Hospital Surabaya

Chesia Christiani Liuwan, Evy Ervianti, Rahmadewi

Department of Dermatology and Venerology, School of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Dr. Soetomo General Hospital,

Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: Acne Vulgaris, Doxycycline, Oral Antibiotic, Lehmann, Plewig and Kligman

Abstract: Introduction: Acne vulgaris (AV) is a common skin disease, affecting more than 85% of adolescents and

often continuing into adulthood. The pathogenesis of acne involves 4 main processes: follicular

hyperproliferation, excess sebum production, inflammation, and proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes.

Although acne vulgaris is not an infection, the normal resident, Propionibacterium acnes, is the stimulus for

inflammation in acne vulgaris, and a reduction in P. acnes populations is usually accompanied by clinical

improvement. Objective: The aim of this study is to evaluate the use of oral antibiotic treatment in patients

with acne vulgaris at dermatovenereology outpatient clinic dr.Soetomo general hospital. Methods: This is a

retrospective study which analyze the data from medical records. Result: Among 475 patients, 63,37% has

been diagnosed AV moderate or AV Papulopustular grade 3-4. Doxycycline is the first choice oral

antibiotic used to treat Acne Vulgaris, used in 98,53% cases, with the duration between 4-8 weeks in

54,36% cases. There are good improvement, shown as decline severity index in diagnosis (before oral

antibiotic treatment is AV moderate at 65,37% and after treatment is AV mild at 68,90%) , after the patients

get the treatment. Conclusion: Doxycycline is effective as first line oral antibiotic to treat moderate and

severe acne vulgaris in Dr.Soetomo general hospital.

1 INTRODUCTION

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis

notable for open or closed comedones (blackheads

and whiteheads) and inflammatory lesions, including

papules, pustules, or nodules (also known as cysts)

(Collier, et al., 2007). AV is a multifactorial

inflammatory disease affecting the pilosebaceous

follicles of the skin. The current understanding of

AV pathogenesis is continuously evolving. Key

pathogenic factors that play an important role in the

development of AV are follicular hyper

keratinization, microbial colonization with

Propionibacterium acnes, sebum production, and

complex inflammatory mechanisms involving both

innate and acquired immunity. In addition, studies

have suggested that neuroendocrine regulatory

mechanisms, diet, and genetic and nongenetic

factors all may contribute to the multifactorial

process of AV pathogenesis (Zaenglein, et al.,

2016).

AV is a common skin disease, especially in

adolescents and young adults. AV affects

approximately 85% of teenagers, but can occur in

most age groups and can persist into adulthood.

There is no mortality associated with AV, but there

is often significant physical and psychological

morbidity, such as permanent scarring, poor self-

image, depression, and anxiety (Lehman, et al.,

2002).

Antibiotic therapy is a time-honored practice

in AV treatment. Although AV is not an infection,

the normal resident, Propionibacterium acnes, is the

stimulus for inflammation in acne, and a reduction in

P. acnes populations is usually accompanied by

clinical improvement. Many AV patients is

effectively treated with the use of long-term

antibiotic regimens, and the practice is generally

considered to be safe and effective (Webster and

Graber, 2008).

The aim of this study is to evaluate

the use of oral antibiotic treatment in patients with

AV at dermatovenereology outpatient clinic

dr.Soetomo general hospital.

338

Liuwan, C., Ervianti, E. and Rahmadewi, .

A Retrospective Study: Acne Vulgaris with Oral Antibiotic Treatment at Dermatovenereology Outpatient Clinic Dr. Soetomo General Hospital Surabaya.

DOI: 10.5220/0008157003380342

In Proceedings of the 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology (RCD 2018), pages 338-342

ISBN: 978-989-758-494-7

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 METHODS

This study is a retrospective study that analyze the

data of AV that we get based on medical record

during January 2013 until December 2015. We only

analyze the new patients who got oral antibiotic as

one of the treatment choice in dermato-venereology

outpatient clinic.

3 RESULTS

There were 2.525 new patients who diagnosed with

AV and got treatment from Dermato-venereology

outpatient clinic in Dr.Soetomo General Hospital,

Surabaya from 2013 until 2015. There were 475

patients (18,81%) given oral antibiotic. Table 1

shown the distribution of the diagnose and therapy.

Of 475 patients, 301 patients (63,37%) has been

diagnosed AV moderate or AV Papulopustular grade

3-4. Doxycycline is the most frequent oral antibiotic

used to treat AV in Dr.Soetomo General Hospital.

From 475 patients with oral antibiotic treatment,

only 283 patients (59,75%) control to dermato-

venereology outpatient clinic. Of 283 patients, 195

patients show a good improvement during the

second visit (data not shown). The duration of the

treatment depends on the amount of visitation

recorded. Most of them, 54,36%, have the treatment

between 4-8 weeks. The detail is shown in Table 2.

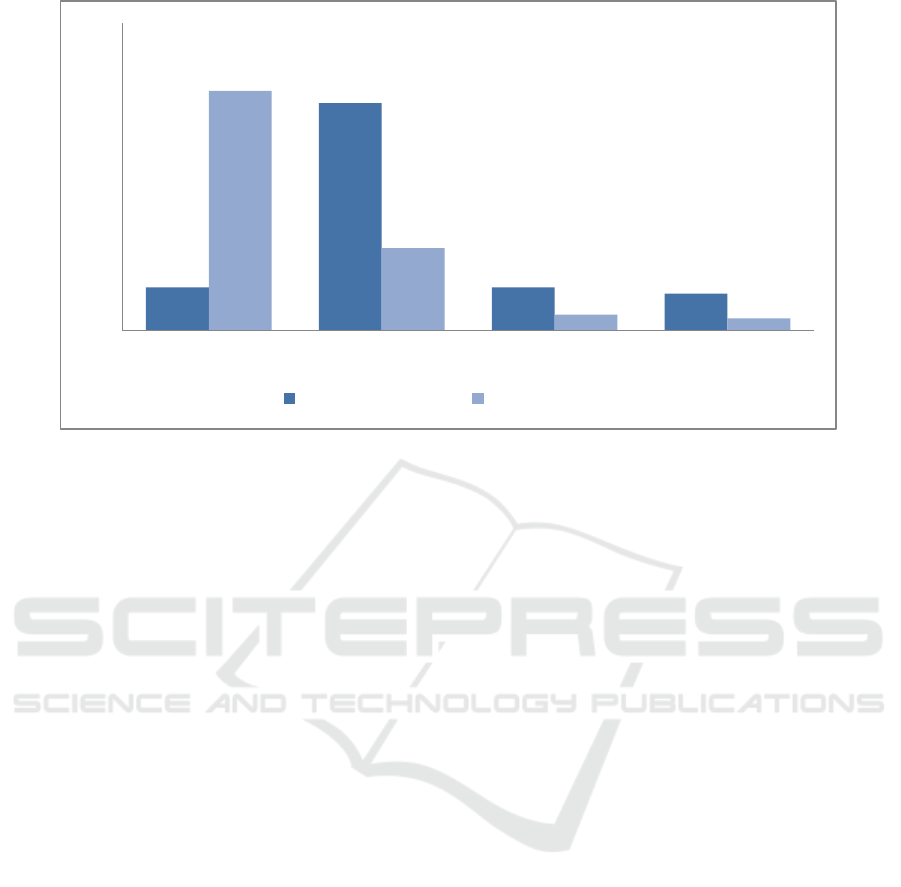

Figure 1 shows the comparison diagnose before

and after oral antibiotic treatment. AV moderate was

the most diagnose made before the treatment (185

among 283 patients, 65,37%) while after the

treatment most patients was diagnosed as AV mild

(195 among 283 patients,68,90%).

4 DISSCUSSION

AV is a multifactorial, pleomorphic skin disease of

the pilosebaceous follicles characterized by a

variety of noninflamed (open and closed

comedones) and inflamed (macules, papules,

pustules and nodules) lesions. Microcomedones

(earliest subclinical lesions) are thought to be the

precursor lesions that can then develop into non-

inflamed and ∕ or inflamed lesions. Although a

common disease, the etiology of acne is not yet fully

elucidated and is thought to be a multifactorial

process. Androgens, excessive sebum production,

hyper-proliferation and abnormal differentiation of

the follicular infundibulum, changes in the microbial

flora, as well as inflammation and immunological

Table 1: Diagnose and Therapy of Acne Vulgaris.

Information Amount Percenta

g

e

(

%

)

Dia

g

nose / AV Severit

y

AVMil

d

*

/ Komedonal-Pa

p

ulo

p

ustular

g

rade 1-2

**

68 14,31

AV Moderate

*

/Pa

p

ulo

p

ustular

g

rade 3-4

**

301 63,37

AV Severe

*

53 11,16

AV Kon

g

lobata

**

53 11,16

Total 475 100

Thera

py

Dox

y

c

y

cline 468 98,53

Er

y

throm

y

cin 4 0,84

Clindam

y

cin 2 0,42

Cefixime 1 0,21

Total 475 100

*)

Lehmann Criteria

**)

Plewig and Kligman Criteria

Table 2: Durations of Treatment.

Duration of treatment Amount Precentage (%)

<4 weeks 87 30,74

4-8 weeks 140 49,48

9-12 weeks 6 2,12

13-18 weeks 6 2,12

>18 weeks 7 2,47

Without data 37 13,07

Total 283 100

A Retrospective Study: Acne Vulgaris with Oral Antibiotic Treatment at Dermatovenereology Outpatient Clinic Dr. Soetomo General

Hospital Surabaya

339

Figure 1. Distribution of AV diagnose before and after treatment.

host reactions are considered the major contributors

to acne pathogenesis (Shaheen and Gonzales, 2012).

Plewig and Kligman divide AV into three

categories, (1) comedonal acne, (2) papulopustular

acne, and (3) acne conglobata. Comedonal acne

mean that the lesions are dominantly open and

closed comedones. Some inflammatory lesions may

be, and frequently are present, but there are never

more than five on one side of the face. The severity

of comedonal acne is measured as grade I: less than

10 comedones on one side, grade II : 10-25

comedones on one side, grade III: 25-50 comedones

on one side, grade IV: above 50 on one side. Papulo-

pustular acne is by far the commonest type in mid

adolescence. Actually, it is a mixture of comedones

and inflammatory lesions which are either pustules

or papules. Assignment to this category is based

solely on the prevalence of inflammatory lesions,

regardless of the number of comedones. Grade I:

less than 10 on one side, grade II: 10-20 on one side,

grade III: 20-30 on one side, grade IV: more than 30

on one side. By definition, acne conglobate is never

mild. The disease is usually appeared with nodul and

cystic form with severe inflammation.

6

Lehmann

also divides AV into three categories, (1) mild, (2)

moderate, and (3) severe. Mild acne character is <20

comedones, or <15 inflammatory lesions, or total

lesion count <30. Moderate acne is 20-100

comedones, or 15-50 inflammatory lesions, or cyst <

5, or total lesion count 30-125. Severe acne >5

cysts, or total comedones count >100, or total

inflammatory count >50, or total lesion count > 25.

Inflammatory lesion in Lehmann categories is papul

and pustul (Lehmann, et al., 2002)

From Table 1, we can see that most of the

patients is diagnosed with AV moderate in Lehmann

categories, equivalent with papulopustular grade 3-4

in Plewig and Kligman categories. Before 2015,

Plewig and Kligman criteria was used to diagnose

acne vulgaris in Dr.Soetomo general hospital. After

Kelompok Studi Dermatologi Kosmetik Indonesia

(KSDKI) set Lehmann criteria as standard criteria to

diagnose acne vulgaris, we used Lehmann criteria at

Dr.Soetomo general hospital. This is the reason there

were some differentiations in acne vulgaris diagnose

at dermato-venereology outpatient’s medical records

during 2013-2015.

Without treatment, acne is generally expected to

spontaneously regress during the late teenaged or

early adulthood years. However, a significant

number of patients experience persistent acne or

develop new-onset adult acne after adolescence

(Collier, et al., 2007). Systemic antibiotics have

been a mainstay of acne treatment for years. They

are indicated for use in moderate to severe

inflammatory acne and should be used in

combination with a topical retinoid and Benzoyl

Peroxide. Evidence supports the efficacy of

tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline,

erythromycin, and azithromycin to treat AV

(Zaenglein, et al., 2016).

The tetracycline class of antibiotics, including

doxycycline and minocycline as second generation

of tetracycline, should be considered first-line

therapy in moderate to severe acne, except when

contraindicated because of other circumstances (ie,

35

185

35

30

195

67

13

10

0

50

100

150

200

250

AVMild AVModerate AVSevere AVKonglobata

BeforeTreatment AfterTreatment

RCD 2018 - The 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology 2018

340

pregnancy, below 8 years of age, or allergy). The

antibiotics of the tetracycline class work by

inhibiting protein synthesis by binding the 30S

subunit of the bacterial ribosome. This class also has

notable anti inflammatory effects, including

inhibiting chemotaxis and metalloproteinase activity

(Zaenglein, et al., 2016). Tetracycline, often dosed

at 500 mg twice daily for acne, must be taken on an

empty stomach (1 hour before eating or 2 hours after

eating). Ingestion with food and especially dairy

products can block the absorption of tetracycline in

the gut. Tetracycline can frequently cause

gastrointestinal upset and may very rarely cause

esophagitis and pancreatitis (Webster and Graber,

2008).

Doxycycline, a second-generation member of

the tetracycline family, is often dosed at 100 mg

twice daily to give optimal antibacterial effects.

Unlike tetracycline, doxycycline may be taken with

food. However, doxycycline has more potential to

induce a phototoxic reaction than tetracycline and

extreme care should be used when prescribing

doxycycline in the summer months (Webster and

Graber, 2008). According to Kelompok Studi

Dermatologi Kosmetik Indonesia (KSDKI) and

Panduan Praktik Klinis Perhimpunan Dokter

Spesialis Kulit dan Kelamin Indonesia

(PERDOSKI), doxycycline is a first line oral

antiobiotic to treat AV moderate with the dose 50-

100 mg, 1-2 times daily (Wasitaatmaja, et al., 2016;

Anon, 2017). In Dr.Soetomo dermato-venereology

outpatients clinic, doxycycline was used as oral

antibiotic treatment in 98,53% AV patients.

Another second-generation tetracycline,

minocycline, is also commonly dosed at 100 mg

twice daily for acne, although 1 mg/kg has been

shown to be an effective dosage for the average acne

patient and one with fewer side effects. Like

doxycycline, minocycline can be taken with food.

Unlike the other tetracyclines, the minocycline

chemical structure has a large side chain that

increases its side effect profile. Because of the high

lipophilicity of minocycline, it can cross the blood–

brain barrier and may induce vestibular disturbances,

such as dizziness, vertigo, and ataxia. A blue– gray

discoloration of the skin may be seen with long-term

minocycline use. Rarely, minocycline may induce a

serum sickness-like reaction characterized by

arthralgias, urticaria, fever, and lymphadenopathy.

When this occurs, it typically starts just days to

weeks after beginning minocycline. Other less

common side effects of minocycline include drug

induced lupus-like disease, vasculitis and hepatic

failure (Webster and Graber, 2008).

Erythromycin

and azithromycin have also been used in the

treatment of acne. The mechanism of action for the

macrolide class of antibiotics is to bind the 50S

subunit of the bacterial ribosome. Again, there are

some antiinflammatory properties for these

medications, but the mechanisms are not well

understood. Azithromycin has been primarily

studied in the treatment of acne in open label studies

with different pulse dosing regimens ranging from 3

times a week to 4 days a month, with azithromycin

being an effective treatment in the time span

evaluated usually 2 to 3 months. A recent

randomized controlled trial comparing 3 days per

month of azithromycin to daily doxycycline did

show superiority of doxycycline (Zaenglein, et al.,

2016). Beside the high used of doxycycline in

dermato-venereology outpatients clinic, there were 7

patients (1,47%) using other classes of oral

antibiotics, such as erythromycin, clindamycin, and

cefixime. The consideration of using different class

of oral antibiotic usually depends on the history of

doxycycline allergy, pregnancy and lactation.

Unfortunately, there were not enough documentation

in these 7 patient’s medical record.

The intensity of doxycycline penetration is

excellent in the pilosebacea unit, and it takes 6-7

days to reach the pilosebasea gland. Doxycycline

works long-term with a half-life of 18-22 hours.

Therefore, the duration of oral antibiotic therapy for

AV cases is a minimum of 6-8 weeks, a maximum

of 12-18 weeks. The expected clinical effects take 4-

8 weeks. If an individual does not respond to

antibiotics or stops responding, there is no evidence

that increasing the frequency or dose is helpful. Such

strategies increase selective pressure without

increasing efficacy. Antibiotics should be stopped if

no further improvement is evident. Antibiotics

should not be routinely used for maintenance.

Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in acne

(2003) recommends that if antibiotics must be used

for longer than 2 months, benzoyl peroxide should

be used for a minimum of 5–7 days between

antibiotic courses to reduce resistant organisms from

the skin (Williams, et al., 2012). The used of

doxycycline in AV management at Dr.Soetomo

general hospital is already appropriate with the

guideline. The dose and duration is correct to treat

AV moderate or worse. From Figure 1, it is

concluded that using doxycycline is giving a good

result in AV patient because there are a significant

decrease in AV severity (before treatment: AV

moderate 65,37% and after treatment AV moderate:

23.68%, AV mild: 68,90%).

The choice of antibiotic should therefore be

based on the patient’s preference, the side-effect

A Retrospective Study: Acne Vulgaris with Oral Antibiotic Treatment at Dermatovenereology Outpatient Clinic Dr. Soetomo General

Hospital Surabaya

341

profile, and cost. Clinicians also should pay attention

to pharmacokinetic factors that influence the

absorption and tissue distribution for individual

antibiotic agents to better inform on rational dosing

considerations of oral antibiotics for the treatment of

acne vulgaris (Leyden and Rosso, 2011). A general

problem with the tetracycline derivate is the

potential for photosensitivity. Doxycycline was

believed to impair the effectiveness of many types of

hormonal contraception due to CYP450 induction.

Recent research has shown no significant loss of

effectiveness in oral contraceptives while using most

tetracycline antibiotics (including doxycycline),

although many physicians still recommend the use

of barrier contraception for people taking the drug to

prevent unwanted pregnancy. Doxycycline is

categorized by the FDA as a class D drug in

pregnancy. As with all tetracycline antibiotics, it is

contraindicated in pregnancy through infancy and

childhood below eight years of age, due to the

potential for disrupting bone and tooth development.

Doxycycline crosses into breast milk. Although the

dose an infant would receive through breastfeeding

would likely be minimal, it is better to not give

doxycycline to breastfeeding mothers (Zaenglein, et

al., 2016). Although the tetracycline can function in

many ways to be beneficial, the physician should be

well versed in the potential side effects of these

drugs. This detail side effect, interaction, and

pregnancy and lactation status were not well

recorded in dermato-venereology outpatients clinic

so that we could not evaluate any further to this

condition.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The used of doxycycline as first line oral antibiotic

at dermato-venereology outpatient clinic,

Dr.Soetomo general hospital is already appropriate

the guideline and effective to treat acne vulgaris.

The suitable dose and duration also play an

important role of the successful treatment. We

recommend to continue using doxycycline as the

first line oral antibiotic treatment for acne vulgaris.

REFERENCES

Collier, C.N., Haerper, J.C., Camtrell, W.C., Wang, W.,

Foster, K.W., Elewski, B.E., 2007. The prevalence of

acne in adults 20 years and older. J Am Acad

Dermatol,58, pp.56-59..

Zaenglein, A.L., Pathy, A.L., Schlosser, B.J., Alikhan, A.,

Baldwin, H.E., Berson, D.S., et al., 2016. Guideline of

care for management of acne vulgaris. Am Acad

Dermatol, pp.1-64.

Lehmann, H.P., Robinson, K.A., Andrews, J.S., Holloway,

V., Goodman, S.N., 2002. Acne therapy. A

methodologic review. J Am Acad Dermatol, 47,

pp.231-240.

Webster, G.F., Graber, E.M., 2008. Antibiotic treatment

for acne vulgaris. Semin Cutan Med Surg,27, pp.183-

187.

Shaheen, B., Gonzalez, M., 2012. Acne sans P. acnes. J

Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 27(1), pp.1-10.

Plewig, G., Kligman, A.M., 1975. Acne: Classification of

Acne Vulgaris. Berlin: Spinger-Verlag, pp.162-167.

Wasitaatmadja, S.M., Arimuko, A., Norawati, L.,

Bernadette, I., Legiawati, L., 2016. Kelompok Studi

Dermatologi Kosmetik Indonesia. Pedoman Tata

Laksana Akne di Indonesia. 2

nd

ed. Jakarta: Centra

Communication;. pp.1-16.

Anon, 2017. Akne Vulgaris. Panduan Praktik Klinis bagi

dokter spesialis kulit dan kelamin di Indonesia.

Perhimpunan Dokter Spesialis Kulit dan Kelamin

Indonesia.

Williams, H.C., Dellavalle, R.P., Garner, S., 2012. Acne

Vulgaris. Lancet, 379, pp. 361–72.

Leyden, J., Rosso, J., 2011. Oral antibiotic therapy for

acne vulgaris pharmacokinetic and

pharmacodynamics perspectives. Nevada, 4.

RCD 2018 - The 23rd Regional Conference of Dermatology 2018

342