Developing a Conceptual Model for Resilient Community Against

Fire in a Densely Populated Settlement in Surabaya

Retno Indro Putri

1

, Muhammad Zainudin

2

and Adjie Pamungkas

3

1

Postgraduate School, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

2

Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

3

Urban & Regional Planning, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember (ITS), Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: Fire, Community Resilience, Conceptual Model.

Abstract: The purpose of this study was to analyze the factors that affect community resilience and to develop a

conceptual model for a resilient community against disaster caused by fire in Surabaya. Fire is one of the

main threats in Surabaya, and for the last three years the highest occurrence happened in residential areas.

The community resilience factors used in this study was based on the Community Coastal Resilience (CCR)

framework of US/IOWTS (2007). This framework has been modified to measure urban community

resilience against fire hazards. Smart PLS 2.0 was used to analyze the relationship between the factors and

system dynamic modelling was utilized in the development of the conceptual model. The analyses showed

that the factors, which include governance, community and economy, land use and structural design, risk

knowledge, warning and evacuation, emergency response, and disaster recovery has good predictive

influence to the model. The conceptual model itself has three sub models: prevention of fire, action during

fire, and support after fire incidence.

1 INTRODUCTION

Surabaya is the second largest city in Indonesia and

the capital of East Java Province. Surabaya

economic growth is higher than all areas in Java.

Development, urbanisation, and population growth

makes Surabaya more densely populated and

densely built. All these increase the risk of fire in

Surabaya.

In the last five years, the fire incident in

Surabaya has shown an increasing trend of events.

Fire in building category is dominated by fire in

residential building. In 2017, the number of fire

incidents in building category was 372 incidents or

twice as much compared to 2016.

Fire also caused high financial loss as well high

losses of life. In 2016, fires caused 5 deaths, 50

injured and an economic loss of almost thirty billion

rupiah.

According to Sendai Framework (2015), one of

the strategies for disaster risk reduction is to build

resilience against disaster in the communities. This

strategy also applies for reducing the risk of fire

disaster.

Disaster resilience is a combination of three

basic characteristics that includes: (1) the level of

shock that a community can absorb and withstand;

(2) the ability to recover and bounce back from

hazard events; (3) the capacity for learning and

adaptation (Folke, 2002 in US/IOWTS, 2007).

Based on Coastal Community Resilience from

US/IOWTS, it should have eight essential elements:

governance, social and economy, land use and

structural design, risk knowledge, warning and

evacuation, emergency response, and disaster

recovery.

A community that is resilent and have a risk

reduction perspective should have a contigency plan

that includes warning and evacuation, emergency

response and recovery plan (LIPI-UNESCO/ISDR,

2006; Twigg, 2009; Horney et al, 2017). This plan

should be made based on a good risk knowledge

(Twigg 2009; DFID, 2012). Successful

implementation of the risk reduction plan can be

influenced by the community economic capability

and the strength of its social ties with each members

(Cutter 2008; Paton & Johnston 2001). And

Governance is the underlying element that provide

Putri, R., Zainuddin, M. and Pamungkas, A.

Developing a Conceptual Model for Resilient Community Against Fire in a Densely Populated Settlement in Surabaya.

DOI: 10.5220/0007552308290833

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference Postgraduate School (ICPS 2018), pages 829-833

ISBN: 978-989-758-348-3

Copyright

c

2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reser ved

829

an enabling environment for the other elements of

resilient to grow (Twigg, 2009).

Therefore, using a modified CCR framework,

this study aimed to analyze the factors that affect

community resilience which then will be used to

develop a conceptual model for resilient community

against fire hazard.

2 METHODS

A hypothetical model was made based on literature

reviews. A relationship analysis or correlation

between the variables was done to the model using

SmartPLS 2.0. Samples for the model were gathered

from questionnaire filled out by 103 family

representatives in RW 11 Petemon Urban Village,

Surabaya.

Petemon was chosen because it is one of the

urban villages in Surabaya that has experienced fire

incidents. It has a high population and buildings

density, and some members of the community had

received fire preparedness training in the past.

Samples were gathered using simple random

sampling method. The number or samples taken

from each of neighbourhood group is proportional to

the population in each group.

Interview with Dinas Kebakaran (Fire

Department) Surabaya was used to further

understand the system that was used to build

community disaster resilience. A conceptual model

of community resilience against fire was then made

based on the interview and the analysis result.

3 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Coefficient of determination (R

2

) was used to

evaluate the model. This coefficient is a measure of

a model predictive accuracy (Hair et al., 2014).

Evaluation on the coefficient of determination

(R

2

) for predictive accuracy criteria showed a result

of 0.6535, which means that governance, social and

economy, land use and structural design, risk

knowledge, warning and evacuation, emergency

response, and disaster recovery have moderate

influence to community resilience. It can also be

interpreted that the variability of resilience

constructs that can be explained by the seven

exogenous mentioned above were 65.33%, while the

remaining 34.67% was explained by other variables

that are not examined in this research.

The descriptive statistics of the questionnaire

showed that in general Petemon urban village has

good community resilience (Table 1). Three resilient

elements had moderate scores while the remaining

four had good scores. However, further observations

found some improper or weak implementation of

disaster risk reduction.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics.

Variables

Mean

Standard

deviation

Score

Governance (X

1

)

2,94

0,63

Moderate

Social and

economic (X

2

)

0.69

0,33

Good

Land use and

structural design

(X

3

)

3,07

0,59

Good

Risk knowledge

(X

4

)

0.82

0,15

Good

Warning and

evacuation (X

5

)

2,91

0,74

Moderate

Emergency

response (X

6

)

2,71

0,60

Moderate

Disaster

recovery (X

7

)

3,12

0,60

Good

Community

resilience (Y)

0.74

0,27

Good

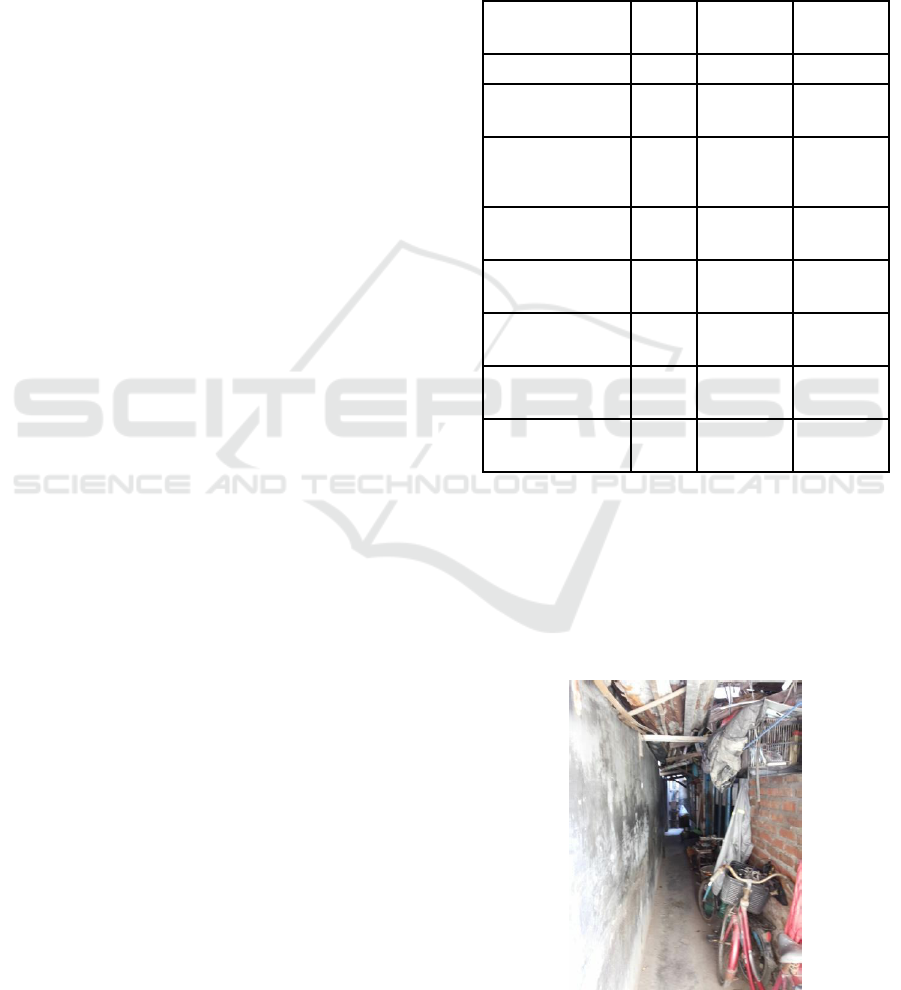

For example, most of the respondents stated that

they have prepared an evacuation route in their

house and on their neighbourhood. However, some

of the evacuation routes do not have adequate

lightings and filled with obstructive items.

Furthermore, the existing evacuation signage and

warning system are not maintained properly.

Figure 1: Inadequate evacuation route.

ICPS 2018 - 2nd International Conference Postgraduate School

830

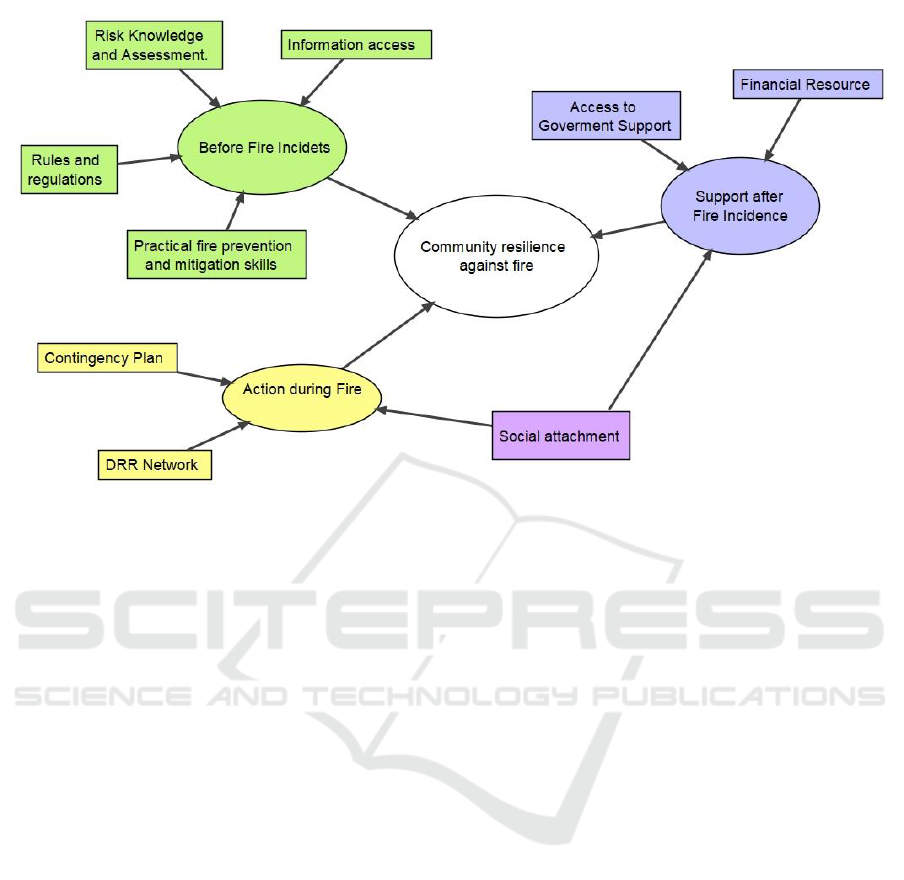

3.1 Conceptual Model for Community

Resilience against Fire

This conceptual model is an iteration of the

hypothetical model.

3.1.1 Before Fire Incidents

This segment focuses on factors that could support

prevention and mitigation measures:

a. Risk knowledge and assessment

An individual who is aware of a threat that could

happen to him/her will take a preventive measure

to avoid or reduce the impact (Lindell and White,

2010 in Sagala, 2014). Furthermore, Pamungkas,

et. al. (2017) stated that increase in risk

knowledge will increase awareness and

precautionary measures.

Therefore, risk knowledge is needed to raise

awareness about the fire hazards and based on

that knowledge the community can do an

assessment to identify the gaps between the

vulnerability and capacity that they have. Risk

knowledge could raise awareness that will

encourage people to take actions and the

assessment of the gaps could provide necessary

information on things to improve.

b. Practical fire prevention and mitigation skills

Increase awareness of a hazard that is not

accompanied by capabilities to avert the threat

will not encourage people to take protective

actions (Djalante & Thomalla, 2010). However,

this preventive and mitigation action should be

something that can be implemented by the

community; thus, it should be a practical

measures and skills that are easy to do.

c. Information access

Vulnerable people need to know about the

hazards and risks that they face. They also need

to know about the technology, practices and

measures to prevent and mitigate the impact of

those risks. Access to this information is needed

to enable continuous learning and adaptation on

preventing fire incidents and in risk reduction

innovations.

Therefore, the communication method for

distribution of this information has to be an

integral part of the resilient building (Twigg,

2004).

d. Rules and regulations

Rules and regulations that are made with risk-

reduction perspectives would encourage

resilience building (Twigg, 2009). It should be

adaptive and understand the need and limitation

of the community in which it will be

implemented.

Figure 2: Conceptual model for community resilience against fire.

Developing a Conceptual Model for Resilient Community Against Fire in a Densely Populated Settlement in Surabaya

831

Surveillance and maintenance procedure should

also be considered to ensure proper implementation.

The effectiveness, commitment and accountability

of community leaders in the implementation of DRR

will support the successful implementation of

resilient building (Lebel et.al, 2006).

3.1.2 Action during Fire

Main focus of this segment is preparedness for

effective action plan that can enable the community

to absorb the impact of fire incident.

a. Contingency Plan

One of the characteristic of resilient community

is the existence of good contingency plan (Arbon

et al, 2013). The contingency plan should

encourage involvement from the community

members in its creation and implementation.

Community involvement in problem

identification, formulation of the plan, and

finding the solution, will foster commitment, a

sense of togetherness, and problem-focused

coping (Paton & Johnston, 2001).

The contingency plan should include:

warning system, evacuation plan and procedures,

and emergency response plan.

b. DRR Network

A strong network will support local authorities

and community resilience against disaster

(Twigg, 2009). The existence of networks

between government, local community and third

parties, such as NGOs or the private sector, can

help cover the shortcomings of local

communities in the provision of facilities and

infrastructure for disaster risk reduction.

c. Sense of community

According to IFRC (2014) the higher the social

cohesion of a society, the higher the ability of

that community to overcome stress and shocks

from disaster. In the time of disaster, sense of

togetherness and attachment could encourage

mutual assistance (gotong royong).

3.1.3 Support after Fire Incidence

This segment focuses on the community capabilities

to bounce back after disaster strikes

a. Financial resource

Recovery requires resources to implement.

Sources of this resource are own resources,

extended family or institutional and most

household usually rely on more than one source

(Lindell, 2013).

Financial resource is one of the main factors

that can enable fast disaster recovery. The source

for this can be from personal savings, insurance,

cooperative savings, or support from

government.

b. Sense of community

The impact of lack of financial resource can be

minimized when there is a strong sense of

community among the member of the

community. A feeling of togetherness in facing a

disaster and attachment to people and place

could encourage people to help each other (Paton

and Johnston, 2001).

c. Access to government support

Government support is one of the supporting

capabilities for disaster recovery (Lindell, 2013).

This support can be in the form of financial help,

temporary shelter or housing, or the reparation

and rehabilitation of public facilities and

infrastructures.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This conceptual model of community resilience

against fire disaster is made based on the

understanding of the formation of community

disaster resilience. The conceptual model consists of

three sub-models.

By dividing the conceptual model into three sub-

models, the resilience development can concentrate

on the sub-models that need attention.

REFERENCES

Arbon, P.A., et al. 2013. How Do We Measure and Build

Resilience Against Disaster in Communities and

Households? Torrens Resilience Institute. Adelaide.

Cutter, S.L. et al. 2008. A place-based model for

understanding community resilience to natural

disasters. Global Environmental Change, 18. 598-606.

Djalante, R.,& F.Thomalla. 2010. Community Resilience

to natural hazards and climate change impacts: a

review of definitions and operational frameworks. 5th

Annual International Workshop & Expo on Sumatra

Tsunami Disaster & Recovery.

Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., and Sarstedt, M.

(2014). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural

Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). California: SAGE

Publications, Inc.

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent

Societies. 2014. IFRC Framework for Community

Resilience. International Federation of Red Cross and

Red Crescent Societies, Geneva.

Lebel, L., Anderies, J.M., Campbell, B., Folke, C.,

Hatfield-Dodds, S., Hughes, T.P. and Wilson, J., 2006.

Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in

ICPS 2018 - 2nd International Conference Postgraduate School

832

regional social-ecological systems. Ecology and

Society, 11(1).

Lindell, M.K., 2013. Recovery and reconstruction after

disaster. In Encyclopedia of natural hazards (pp. 812-

824). Springer, Dordrecht.

LIPI-UNESCO/ISDR. 2006. Kajian Kesiapsiagaan

Masyarakat dalam Mengantisipasi Bencana Gempa

Bumi & Tsunami. Deputi Ilmu Pengetahuan Kebumian

Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia, Jakarta.

Pamungkas, A., et al. 2016. A Conceptual Model for

Water Sensitive City in Surabaya. IOP Conf,Series:

Earth and Environmental Science

Pamungkas, Adjie, et al. Making a Low Risk Kampong to

Urban Fire. Asian Journal of Applied Sciences, Apr.

2017,

Paton, D., & Johnston, D. 2001. Disasters and

communities: Vulnerability, resilience and

preparedness. Disaster Prevention and Management,

10(4), 270-227

Sagala, S., et al. 2014. Perilaku dan kesiapsiagaan terkait

kebakaran pada penghuni permukiman padat kota

bandung. Forum Geografi, 28 (1).

Twigg, J. 2004. Disaster risk reduction: mitigation and

preparedness in development and emergency

programming. Overseas Development Studies (ODI).

Twigg, J. 2009. Characteristic of a Disaster-Resilient

Community, A Guidence Note Version 2. November

2009.

U.S. Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System Program.

2007. How Resilient is Your Coastal Community? A

Guide for Evaluating Coastal Community Resilience

to Tsunamis and Other Coastal Hazards. U.S. Indian

Ocean Tsunami Warning System Program, Bangkok,

Thailand. 144 p.

Developing a Conceptual Model for Resilient Community Against Fire in a Densely Populated Settlement in Surabaya

833