Tax And Samin: A Way To Understand Tax Compliance in The

Samin People

Selvia Eka Aristantia

1

and Hamidah

2

Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya-Indonesia

1

selviaekaaristantia@gmail.com,

2

hamidah_unair@yahoo.com

Keywords:

Ethnography, Postcolonial Theory, Samin People, Tax Compliance.

Abstract: This study aims to determine the meaning of tax compliance according to the local wisdom of the Samin

people, in addition to how their interpretation of tax compliance is based on particular spiritual and cultural

values. This study used a qualitative ethnographic research approach, which enables understanding of the

habits, customs, or cultures of organizations or communities, and allowed the researchers to interpret the

Samin people’s concept of tax compliance. Samin teaching is guided by the idea of manunggaling kawula

gusti, which demonstrates that the teaching of kindness is reflected in the tax compliance behavior of the

Samin people. This behavior is inseparable from the teachings of the Samin people’s life philosophy, which

includes four elements (panggada, pangrasa, pangrungu, and pangawas) that can put a person at the highest

level of him/herself. The researchers wanted to focus on the behavior of the Samin people, who are well

known for their unique views on taxation. In addition, by using an ethnographic approach in the research field

of taxation, this study will provide a broader and deeper insight into tax research.

1 INTRODUCTION

"Accounting exists and evolves over time. Past

accounting is history, current accounting is a reality,

and future accounting is a dream or a delusion which can

come true in reality” (Lutfillah & Sukoharsono, 2013).

Taxation, as one of the domains of accounting, has

been around since Imperial times. In fact, in those

times, it was the largest source of income for the

Kingdom of Indonesia (Lutfillah & Sukoharsono,

2013; Sukoharsono & Lutfillah, 2008). However, the

tax to the king, known as a ‘tribute’ by the people,

could be given in the form of farm products or

livestock. No rewards were given by the king to the

people for the payment of tribute because it was only

used for the benefit of the kingdom (Nawangsari,

2017). Meanwhile, in the Dutch colonial period, the

people of Indonesia were also required to deliver farm

products as tax, which was called Contingenten

(Dekker, 1913). The term tax itself only emerged in

the 19

th

century on the Java islands, which is when it

was colonized by the British. At that time, a landrente

charge was created by Thomas Stafford Raffles

(Swim, 2003).

In the colonial period, tax exploitation was used

for the benefit of the colonizers. The collection was

carried out with no regard for justice and human

rights, and, for this reason, Indonesians suffered

terribly (Purnami, 2015). For this reason, compliance

levels were very low, and various forms of resistance

emerged against the colonial power, one of which was

undertaken by the Samin people.

The Samin people inhabit eastern and central

Java, in Blora and Bojonegoro. They are well known

in society for persistently refusing to pay taxes

(Hardiansyah, 2014). In this regard, the issue of tax

has become important in the actions of the Samin

people and has invited much debate.

With regard to a general definition, tax

compliance is a condition in which the taxpayer has

fulfilled all tax obligations according to established

rules. Tax compliance can be understood as complex

behavior because of the many factors that lie behind

it. Therefore, tax compliance is an interesting

phenomenon, which, up to now, has been frequently

researched and discussed. Chuenjit (2014) states that

the phenomenon of tax compliance can be viewed as

a result of the culture of taxation. In this regard, a

culture of taxation relates to a person’s way of life or

life view, including a collection of ideas, values, and

behaviors, which result in a relationship between

different interested parties in shaping the tax system.

A culture of taxation is an important factor in the

success of an organization’s tax systems and the

Aristantia, S. and Hamidah, .

Tax And Samin: A Way To Understand Tax Compliance in The Samin People.

In Proceedings of the Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics Symposium 2018 on Special Session for Indonesian Study (JCAE 2018) - Contemporary Accounting Studies in

Indonesia, pages 167-173

ISBN: 978-989-758-339-1

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

167

direction of the organization, and it will affect the

way people or groups in the tax system interact with

each other.

In addition, Cummings (2004) states that culture

has an influence on tax compliance behavior. In this

regard, “accounting practices in the past were closely

related to aspects of social life and the culture of

society” (Burchell, Clubb & Hopwood 1985;

Hopwood 1987; Miller & Napier, 1993). Research

into accounting and taxation in regard to local

wisdom has begun to grow. It is important to know

the culture of taxation so as to achieve success in its

collection (Chuenjit, 2014). Research on the people

of Samin has also been carried out from various

perspectives, such as culture, marriage customs,

religion, language, education, and politics, either by

local (Hardiansyah, 2015; Rosyid, 2013; Subarkah &

Wicaksono, 2014) or international scholars (Benda &

Castle, 1969; Rohman, 2010; Widodo, 2007).

Different from previous research, the present

study focuses on exploring an economic issue relating

to taxation and the Samin people. In accordance with

the habits, traditions, and culture of the Samin people,

the researchers wanted to examine the meaning of tax

compliance according to the Samin people in the hope

that the research can provide additional information,

insight, and knowledge about the existence of a

unique culture (i.e. local wisdom) that results in

particular tax behavior; further, it can also be the

subject of study and evaluation for local governments

in response to a given behavior or culture in the face

of tax implementation.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND

THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

As outlined below, this study utilizes several related

theories.

2.1 Theory of Planned Behavior

Human behavior can be simple or complex because

people can have different perspectives and

dispositions. According to the Theory of Planned

Behavior (TPB), the most important determinant of a

person’s behavior is the individual’s intention to

display his/her behavior. In TPB, Ajzen (2015) adds

one factor in relation to determining the intention of

perceived behavioral control. Perceived behavioral

control is an individual’s perception of the control

he/she has with respect to certain behaviors. These

factors refer to individual perceptions of the ease or

difficulty of generating certain behaviors, and they

are assumed to reflect past experiences as well as

anticipated obstacles. In this regard, this factor,

which relates to subjective norms and perceived

behavioral control, can predict the intention of

individuals in performing certain behaviors (Ajzen,

2015).

2.1.1 Normative Beliefs

Normative beliefs produce components called

subjective norms, which represent one’s perceptions

about someone else’s behavior. A subjective norm

indicates the extent to which the social environment

affects the behavior of an individual (Ajzen, 2015).

2.1.2 Control Beliefs

Control beliefs determine the level of perceived

behavioral control, which describes the feeling of

self-efficacy or the ability of the individual to behave

in a particular way. Perceived behavior control refers

to a belief about the presence or absence of factors

that facilitate or deter individuals from performing a

given behavior. In this regard, someone will perform

a certain behavior if that person evaluates the

behavior positively (Ajzen, 2015).

2.2 Postcolonial Theory

Uncomfortable images of the colonized can cause a

great deal of criticism. There is a possibility for the

imperialism of the way of thinking raises an attempt

to restore the way of thinking, which then results in

postcolonial discourse or study (Gandhi, 2001).

Postcolonialism aims to examine the practices of

colonialism, which gave birth to a life full of racism

and unequal power relations. Postcolonial discourse,

as a tool of criticism, clearly sees how the connections

between culture, society, and the economy are

controlled for the interests of the dominant class (or

the center). Postcolonial theory attempts to dismantle

the myths that “dwarf” the critical powers of mastery

through cultural movements and consciousness. In

this sense, it can be said that the postcolonial is daily

resistance (Anderson, 1999).

In short, postcolonial theory addresses the

conditions of colonialism and the circumstances

thereafter. Postcolonial theories relate to the situation

in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, in addition

to focusing on indigenous cultures that are oppressed

under the rule of colonialism. This theory also relates

to representations of race, ethnicity, and the formation

of a nation or state.

JCAE Symposium 2018 – Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics Symposium 2018 on Special Session for Indonesian Study

168

2.3 Tax Compliance

Tax compliance refers to the fulfillment of tax

obligations undertaken by taxpayers in order to

contribute to the development of society, and it is

expected to be given voluntarily. Tax compliance has

become an important area, considering that

Indonesia’s taxation system adopts a self-assessment

system in which its process affords absolute trust in

taxpayer to calculate, pay, and report their

obligations.

According to Article 1 of the DGT Policy

(Keputusan Direktorat Jenderal Pajak Nomor KEP-

213/PJ/2003): “For tax compliance, a taxpayer is

stipulated by the Directorate General of Taxes as a

someone who meets certain criteria as referred to in

Keputusan Menteri Keuangan Nomor 544/KMK.04

/2000 on Taxpayer Criteria that can be given Return

of Introduction of Excess Tax Payment as amended

by Keputusan Menteri Keuangan Nomor

235/KMK.03/2003.”

2.4 Samin (Sami-sami Amin)

The Samin people are Javanese, and they have unique

characteristics different from Javanese people in

general. The Samin people embrace a worldview that

contains a particular value system (Melalatoa, 1995),

and this view of life encompasses a doctrine, often

called Saminism, that was embodied in the Samin

movement against Dutch colonial power.

The history of Samin’s name comes from the gang

movement of Saminism led by Surowidjoyo or Raden

Suratmoko, who was the son of a regent of Suromoto.

He was concerned that the Indonesian people were

being forced to pay taxes arbitrarily by the colonial

government, while the tax collectors were none other

than natives who worked for the colonial government.

The tax payable from farmers was very high, and if

they could not pay, they had to give up their goods in

the form of livestock, staple food, and household

items. Seeing the behavior of the natives who became

Dutch henchmen, Raden Surowidjoyo went to

Kadipaten and joined a band of robbers named Tiyang

Sami-sami Amin, which means a group of people of

the same destiny and fate.

3 RESEARCH METHODS

This research utilized a qualitative research approach,

with inductive thinking, which is used to discover the

meaning or understanding behind a phenomenon; in

this regard, the information obtained is real

information (Moleong, 2009). In accordance with

research that aims to understand the habits, customs,

or culture of an organization, the correct paradigm for

achieving the purposes of such research is the

interpretive paradigm, since it focuses more on the

social realities that are consciously and actively built

by individuals (Soetriono & Hanafie, 2007).

To understand and interpret the Samin people’s

concept of tax compliance, this research used an

ethnographic approach. Ethnography is a method

commonly used to understand the world from the

point of view of indigenous peoples (Spradley, 1997).

It is a research method that aims to examine an object

in relation to the culture or social society of a

community by describing the way people think, live,

behave, and exist as they are (Muhadjir, 2007).

Sukoharsono (2009) argues that ethnographic

research can also be utilized in exploring and

describing accounting life in the midst of social

interactions. Ethnographic research does not just look

at human behavior, but it also interprets the behavior

that can be framed in the life of accounting science

The meaning of the concept of tax compliance in

this study emphasizes local wisdom, i.e. meaning

based on the spiritual values/culture that exists in

Samin society. Research methods using local wisdom

are supported by scholars. In this sense, Budiman

(1984) states that there is a need to explore the

elements of the philosophy of social science and

research methods that result from the ideology/local

wisdom of the Indonesian nation, given that the

majority of the philosophy of social science comes

from the West, which is not necessarily in accordance

with the state of Indonesian society.

The research location was Dusun Jepang,

Margomulyo, Bojonegoro, where the majority of the

Samin and the original offspring of Samin

Surosentiko (4

th

generation) live. Data collection

techniques in this study were participant observation

and open, in-depth interviews with informants.

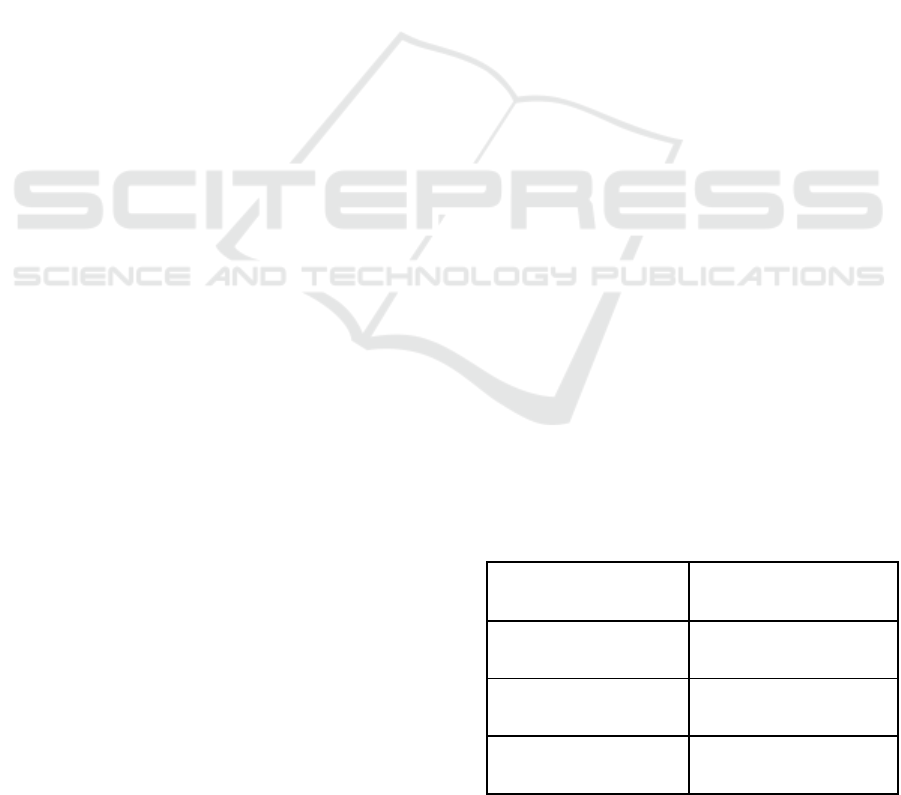

Table 1: List of Informants

Name Role

Mbah Hardjo Kardi Descendants of Samin

Pak Miran

Dusun Jepang Villagers

Pak Iswanto

Village Secretary

Tax And Samin: A Way To Understand Tax Compliance in The Samin People

169

4 RESULTS

Samin Surosentiko is the pioneer of Samin teaching.

Samin comes from “Sami-sami amin … Sami-sami

jowone sami-sami negarane,” meaning that they are

a group of people with the same destiny. If they are

united, they can defend the country. Dusun Jepang,

Margomulyo, Bojonegoro is one of the areas where

the Samin people live, and most of the population are

followers of Saminism. In the past, access to the

village was difficult because it is in the middle of teak

forests and rocky dirt roads. However, the village is

now open, which can be seen from the many visits by

outsiders to the village. In this sense, the village is

now easily accessible. At the present time, many

people refer to the Samin as a tribe; however, Mbah

Hardjo Kardi, as a descendant of Samin Surosentiko,

states unequivocally that this is wrong. Samin people

include tribal Javanese. The Samin people can be

understood as a society that has its own uniqueness

and has undergone many changes, although there are

still values that have been maintained.

One aspect of uniqueness can be seen in Mbah

Hardjo Kardi’s typical dress: a headband, a batik

shirt, and black pants to the ankles. The economic life

of the Samin people is considered as advanced. In this

regard, the Samin people feel they have enough in

their lives: no exaggeration and no shortage:

“Manungsa niku nek nuruti kurang nggih kurang

terus to,” according to Mbah Hardjo Kardi.

The majority of the Samin people are farmers and

cattlemen. According to the Samin people, being a

farmer is the cleanest, nicest, and most honest

profession. They avoid trading because they assume

that this is opening oneself up to lies. However,

according to Mbah Hardjo Kardi, the Samin people

may trade, but they must prioritize honesty and

transparency in determining any profit. It is evident

that there are small stores in the Samin people’s

settlements:

“Dagang niku angsal nanging ojo geroh. Satus

nggih muni satus. Mek bati yo mek bati. Kulakan

kaleh ewu ajeng mek bati pinten mawon nggih

dudohke.” (Trading is allowed, but it is forbidden to

lie. If it costs a hundred rupiah, say a hundred rupiah.

If you want to make a profit, that’s okay, but show

how much profit you get).

Besides an emphasis on honesty, the Samin

people also have hereditary teachings, and when they

apply these teaching they can become great human

beings (Mbah Hardjo Kardi gives two thumbs up):

“Ojo ngantos nglakoni drengi, srei, dahwen,

kemeren lan siya marang sapadha-padhaning urip,

kudune gotong royong, rukun. Mpon ngantek mbedo

sepodo mirang sepodo. Ngeplak anak nggitik bojo

mboten angsal nopo maleh tonggo.” (Do not be

jealous, envious, or arbitrary to others; help each

other be harmonious).

The Samin did not want to pay taxes in the

colonial period because, at that time, the Indonesians

did not rule themselves and the Dutch were very

arbitrarily in regard to collecting taxes. This behavior

is in accordance with postcolonial theory, which

focuses on indigenous cultures as the oppressed

cultures of the rule of colonialism. Mbah Hardjo

Kardi, with a fiery tone, stated:

“Pajek niku kangge mbangun negoro londo, mriki

dibageni ampas tok.” (Taxes were only used to build

the colonial state, while Indonesians got nothing).

“Bapake niki ngantos purun ngrampok kangge

ngingoni rakyat, mboten kangge awake kiyambak.”

(…and Samin Surosentiko had to become a thief to

help the poor people).

So, Samin Surosentiko, who was a pioneer of the

Samin movement against the invaders, advised his

offspring not to pay taxes to the Dutch in the hope that

all his grandchildren could unite as one against them.

In this sense, the purpose of refusing to pay taxes was

like soft warfare, or om sumuruping banyu, which

means like a needle into water.

“Sebab perang iki mau tanpa sarana gegaman

utawa sing diarani senjata, sebab mbah surasentika

emoh mateni, emoh menthung uwong nanging kudu

sabar lan trokal.” (In this war, we do not use

weapons on the ground because Samin Surosentiko

does not want to kill and beat people. Be patient).

This behavior is in accordance with planned

behavior theory, which states that specific behaviors

can be considered as a reflection of past experiences.

It is also shows that normative beliefs produce a

component called subjective norms, which represents

one’s perceptions about the behavior of others.

Further, subjective norms indicate the extent to which

the social environment affects the behavior of an

individual. Samin people are very obedient to

Samin’s teachings. Even through Samin Surosentiko

is dead, his teaching continues. Until the country was

independent, the Samin rejected the taxes because

their lives were lived mainly in the forests.

However, when he heard that the country was

free, Suriokarto Kamidin went to Jakarta to meet with

Pak Karno (President Soekarno) in order to asked him

directly about the truth of the current regulation. After

returning from Jakarta, he immediately told his

grandchildren to obey the government because it

ruled the nation of Indonesia:

JCAE Symposium 2018 – Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics Symposium 2018 on Special Session for Indonesian Study

170

“Wong jowo wis merdika lan wis diperentah karo

wong jowo” (Javanese people are independent and

led by the Java people themselves).

Mbah Hardjo Kardi also supported this idea. In

this regard, he said: “Wong jowo dipimpin wong jowo,

mpun merdika ngge mpun mbayar pajak kangge

mbangun negaranipun kiyambak. Niku paling

diidam-idamken.” (After Indonesia’s independence

led by the people of Java (President Soekarno), Samin

people obeyed the government’s rules, including

paying taxes).

Based on an interview with one of the Jepang

villagers, Mr. Miran, “tax compliance for the Samin

people (i.e. paying tax) should now be given a

thumbs-up, although

Samin people once refused to pay taxes. Now, this

behavior is no longer appropriate for the Samin. It is

the values of obedience that must be followed.”

This was also supported by information from Mr.

Iswanto, as the village secretary of Margomulyo, who

said that “in terms of compliance, Samin people pay

their taxes in the most orderly and timely manner in

their territory. Everyone pays just in time. So, the

negative image that has been inherent about the

Samin people in terms of defying the government and

refusing to pay taxes to this day is not true because

the tax compliance of the Samin people is very good.

They are very disciplined and honest.”

Figure 1: Data monograph 2016 Margomulyo

In addition, Samin people are very concerned

about, and feel obligated towards, the condition of

other community members who are experiencing

difficulties. For example, they are willing to sacrifice

and lend their own money to help neighbors who

cannot pay. The teachings of “Rembug lan

manunggal” (deliberation and upholding

togetherness) form the basis of the Samin people’s

order to create a just and prosperous society. The

Samin people’s compliance with values that they

consider as hereditary is highly respected. The

progress that has been achieved so far is also the result

of compliance, in that they will not break the

promises of their predecessors.

Samin’s teachings are guided by the idea of

“manunggaling kawula gusti,” meaning attaching the

properties of God to a person (Prambadi, 1997). In

understanding the Samin conception of

manunggaling kawula gusti, one is able to do good

things and not harm others. The doctrine contains

deep meaning. Good moral teaching is manifested in

the form of tax compliance by the Samin people, so

as to help the government in the interests of the state.

Good intentions to jointly build the country is

part of the ideals of the Samin people, and it is

expressed through an attitude of tax compliance

consistent with the doctrine of virtue, according to

their philosophy. The life philosophy of the Samin

people, in the form of moral teachings and behavior,

is closer to the order of harmony than has previously

been believed. This philosophy of life is sounded on

the call Panggada, Pangrasa, Pangrungu, and

Pangawas. Panggada refers to the sense of smell that

knows good smells and those that are not fragrant.

This sense of smell relates to the need to be wary of

things that are not good and to avoid them

immediately. Pangrasa means to taste and to

understand where the good and bad deeds are.

Pangrungan, as the sense of hearing, can distinguish

between what should be heard what should not.

Finally, Pangawas, as the sense of sight, serves to see

that which is fine.

These four elements, when executed, will allow

one to place oneself at the highest level of oneself,

namely the noble man of the soul. Apart from the

above four elements, Samin people advise their

grandchildren to do good. They believe that an event

is the result of past deeds. In this sense, compliance

in paying taxes will realize ideals relating to the

development of the country (Nandhur pari, thukul

pari, ngundhuh pari). It is clear that the philosophy of

life of the Samin people is the result of the human

mind having inner power in the quest for good.

Tax And Samin: A Way To Understand Tax Compliance in The Samin People

171

Figure 2: One of the researchers and Mbah Hardjo Kardi

5 CONCLUSIONS

Samin encouraged his followers to do good, which is

reflected in the philosophy of life in Panggada,

Pangrasa, Pangrungu, and Pangawas. The Samin

people highly respect adherence not only to the

teachings of their ancestors but (after Indonesian

independence) also to the government. In this regard,

Samin people teach: “Aja siya marang sapadha-

padhane urip.” In summary, the Samin people

refused to pay taxes in the colonial period. However,

after independence (wong jowo led wong jowo), the

Samin people became the most compliant and

disciplined in their territory with regard to paying

taxes. In this sense, compliance in paying taxes

reflects their goal to contribute to the building of the

country.

REFERENCES

Anderson, B., & Imajiner, K. (1999). Renungan Tentang

Asal-Usul dan Penyebaran Nasionalisme (terj).

Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar-Insist.

Ajzen, I. (2015). Subjective Norm. Retrieved September

22, 2015 from http://people.umass.edu/aizen/sn.html

Benda, H. J., & Castles, L. (1969). The Samin

Movement. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en

Volkenkunde, (2de Afl), 207-240.

Budiasih, I. G. A. N. (2015). Fenomena Akuntabilitas

Perpajakan pada Jaman Bali Kuno: Suatu Studi

Interpretif. Jurnal Akuntansi Multiparadigma, 5(3).

Budiman, A. (1984). Ilmu Sosial di Indonesia: Perlunya

Pendekatan Struktural. Jakarta: PLP2M.409.

Burchell, S., Clubb, C., & Hopwood, A. G. (1985).

Accounting in its social context: towards a history of

value added in the United Kingdom. Accounting,

organizations and Society, 10(4), 381-413

Chua, W. F. (1986). Radical developments in accounting

thought. Accounting review, 601-632.

Chuenjit, P. (2014). The culture of taxation: Definition

and conceptual approaches for tax administration.

Journal of Population and Social Studies [JPSS],

22(1), 14-34.

Cummings, R. C., Martinez-Vazquez, J., McKee, M., &

Torgler, B. (2004). Effects of culture on tax

compliance: A cross check of experimental and survey

evidence.

Dekker, E. D. (1913). De Indische Partij. Haar Wezen en

haar Doel, Bandung.

Gandhi, L., Wahyutri, Y., & Hamidah, N. (2001). Teori

Poskolonial: Upaya Meruntuhkan Hegemoni Barat.

Penerbit Qalam.

Hardiansyah, Dicki. (2014). Perlawanan Masyarakat

Samin terhadap Kebijakan Pajak pada Masa Kolonial.

Retrieved September 22, 2015 from

https://www.academia.edu/10353516/perlawanan_ma

s

yarakat_samin_terhadap_kebijakan_pajak_pada_mas

a _kolonial

Hopwood, A. G. (1987). The archeology of accounting

systems. Accounting, organizations and society, 12(3),

207-234.

Lutfillah, N. Q., & Sukoharsono, E. G. (2013).

Historiografi akuntansi indonesia masa Mataram Kuno

(Abad VII-XI Masehi). Jurnal Akuntansi

Multiparadigma, 4(1).

Melalatoa, M. J. (1995). Ensiklopedi Suku Bangsa

di

Indonesia Jilid LZ. Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan.

Miller, P., & Napier, C. (1993). Genealogies of

calculation. Accounting, Organizations and

Society, 18(7-8), 631-647.

Moleong, L. J. (2009). Qualitative research methodology

(in Bahasa). Rosdakarya, Bandung.

Muhadjir, N. (2007). Metodologi Keilmuan: Paradigma

Kualitatif, Kuantitatif, dan Mixed. Yogyakarta: Rake

Sarasin.

Nawangsari, A. T. (2017). Peran Akuntansi Dalam

Kehidupan Masyarakat Kerajaan Kediri Abad 12-13

M (Doctoral dissertation, Universitas Airlangga).

Purnami, Ni Luh Junia (2015). Perkembangan Perpajakan

Pada Zaman Kerajaan Dan Penjajahan Di Indonesia.

Retrieved Februari 25, 2018 from

https://purnamiap.blogspot.co.id/2015/03/perkembang

anperpajakan-pada-zaman. html

Rohman, A. (2010). Rumours and Realities of Marriage

Practices in Contemporary Samin

Society. Humaniora, 22(2), 113-124.

Rosyid, M. (2013). Konversi Agama Masyarakat Samin:

Studi Kasus di Kudus, Pati, dan

Blora (Doctoral

dissertation, IAIN Walisongo).

Soetriono, S., & Hanafie, R. (2007). Filsafat ilmu dan

metodologi penelitian.

JCAE Symposium 2018 – Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics Symposium 2018 on Special Session for Indonesian Study

172

Spradley, J. P. (1997). Metode Etnografi, terj. Tiara

Wacana, Yogyakarta.

Subarkah, S., & Wicaksono, A. (2014). Perlawanan

Masyarakat Samin (Sedulur Sikep) Atas Kebijakan

Pembangunan Semen Gresik Di Sukolilo Pati (Studi

Kebijakan Berbasis Lingkungan Dan Kearifan Lokal).

Pena Jurnal Ilmu Pengetahuan Dan Teknologi, 26(2).

Sukoharsono, E. G., & Lutfillah, N. Q. (2008). Accounting

in the golden age of Singosari kingdom: A

Foucauldian

perspective. Simposium Nasional

Akuntansi XI.

Sukoharsono, E. G. (2009). Refleksi Ethnografi Kritis:

Pilihan Lain Teknik Riset Akuntansi. Jurnal

Akuntansi, 4(1), 91-109.

Swim, S. (2003). Pengaruh Pola Pikir Masyarakat Hukum

Adat Terhadap Perkembangan Pendaftaran Tanah Di

Karupaten Semarang (Doctoral dissertation, Program

Pascasarjana Universitas Diponegoro).

Triyuwono, I. (2006). Perspektif, Metodologi, dan Teori

Akuntansi Syariah. PT RajaGrafindo Persada.

Widodo, S., & Hasan, F. (2007). Proses transformasi

pertanian dan perubahan sosial budaya pada

masyarakat Samin di Bojonegoro: laporan penelitian

dosen muda. Jurusan Agribisnis, Fakultas Pertanian,

Universitas Trunojo

Tax And Samin: A Way To Understand Tax Compliance in The Samin People

173