A New Approach for SBPM based on Competencies Management

Wafa Triaa

1

, Lilia Gzara

1

and Herve Verjus

2

1

GSCOP, Technology Institute of Grenoble, Grenoble France

2

LISTIC, Universite Savoie Mont Blanc, Annecy, France

Keywords:

BPM, Agile-BPM, SBPM, Collaboration, Competency Management.

Abstract:

In such continuous changing business work environment, traditional BPM has two principal issues: firstly

the model-reality-divide, the typical separation between process’s design and execution. Secondly, the loss

of innovation associated to the lack of internal performers’ implication. To overcome these issues and to

stress continuous adaptation and rapid innovation, BPM has to be agile. Otherwise, an agile enterprise is

basically an enterprise of knowledge and skills. Human dimension the key element of an agile enterprise was

and stills not taken into consideration within BPM. One of the recent solutions to support BPM agility is the

integration of Social Software (SS) principles within BPM leading to the emergence of Social BPM (SBPM).

Although the importance and the innovative ideas of the proposed approaches, they are not able to address all

the identified issues of traditional BPM and to support all the phases of its lifecycle. Thus, in our approach,

we integrate competency management to answer how stakeholders can find the right performers at the right

time for the right type of contribution. It is mainly based on three phases: 1) identification of the required

competencies to fulfil a specific need. Based on a semantic analysis, the system will be able to identify the

required competencies and automatically extract the possible candidates. 2) Then the identified candidates

will be evaluated against our defined criteria (related to time dimension, human dimension, cost dimension,

etc.) to select the relevant ones. 3) Finally, after selecting the relevant performers, the process model will be

adjusted based on the identified competencies. In this paper, we will typically present the first phase.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the advancement of technology over the past

decade and the increase of competition in the in-

dustry, the need for effective management of orga-

nization’s business processes has become more im-

portant than ever before (Ryan., 2009). Priority of

every organization or company is to increase oper-

ational efficiency, reduce costs, improve quality of

their products or services and better manage opera-

tional knowledge. Many organizations are using busi-

ness process management (BPM) as a key component

in automating their processes, increasing standardiza-

tion and improving performance and customer satis-

faction. BPM typically consists of series of activ-

ities for the ongoing improvement of business pro-

cesses that are carried out within an iterative life cy-

cle (Weske, 2012). In addition, business processes

are classified into two main categories depending on

their nature: the first concerns well structured, highly

repetitive processes. These processes are subject to

little change over time and they are often supported

by traditional BPM. The second category concerns

loosely structured processes known as knowledge-

intensive processes which cannot be supported by tra-

ditional BPM (Gottanka, 2012). As it was affirmed by

(Gilbert, 2010) in an example of a large bank, more

of 60% of the processes are knowledge-intensive pro-

cesses known also as ad-hoc processes, not covered

by classical BPM methods. While just 2.5% of them

are highly complex repetitive and allow a substan-

tial automation. Such ad-hoc processes can be seen

as to what (G., 2011) called the accelerated ”pace of

changes” as well as the ”spreading of context infor-

mation and the demand for quickly created process

solutions” of BPM. Furthermore, research in the field

of BPM pays more attention to reduce its incapacity

in order to support ad-hoc processes. The evolution of

BPM over the years suggests that there are still lim-

itations within the different stages of BPM’s lifecy-

cle. One of the main limitations of traditional BPM is

the separation between the process design and execu-

tion, which is often referred to as model-reality divide

(Palmer, 2011). Thus, during process execution, ideas

suggested by internal performers may remain unused

during process design and cannot be shared within

Triaa, W., Gzara, L. and Verjus, H.

A New Approach for SBPM based on Competencies Management.

DOI: 10.5220/0006704706730681

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2018), pages 673-681

ISBN: 978-989-758-298-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

673

the organization (Schmidt, 2009). Owing to the fre-

quently stated fast changing business world and un-

predictability of processes, several works in academia

and industry propose concepts to enable the continu-

ous and rapid adaptation of processes to change. This

capability known as agility considered as inescapable

feature of today’s forward-looking corporates. Thus,

BPM must be agile in order to be able to react quickly

and adequately to internal and external events. One

of the recent solutions to support BPM agility is the

integration of Social Software (SS) principles and

techniques within BPM leading to the emergence of

Social BPM (SBPM). In literature, combination of

BPM and social software is discussed under the terms

subject-oriented BPM (Felishman, 2010), social BPM

(Schmidt, 2009) and BPM 2.0 (Kern, 2015). These

terms refer to the improvement of business processes

that seeks to break down silos by encouraging a more

collaborative and transparent approach. In our pa-

per, we use the term Social BPM to describe the inte-

gration of social software principles within BPM. In

such context, BPM paradigm changes from closed to

open and social. Rather than centrally defining pro-

cesses by the managers and deploying them for exe-

cution by internal performers, business processes can

be reached to a broader class of stakeholders. The in-

tegration of social software with BPM depends on the

companies’ needs. Some of them will only use so-

cial software functionalities for communication, oth-

ers will use it to reduce their time to market, and

yet others will use it for transformation. Actually, in

such continuously changing and turbulent work envi-

ronment, using social software principles to enhance

process adaptation and transformation seems to be

strongly important. While most previous research was

focused on improving the collaboration between the

model creators and internal performers during process

design phase, minor loosely coupled social features

within BPMS are suggested. This is far from enabling

full exploitation of the SBPM benefits and the princi-

ples of social software which have been identified a

long time ago but not properly implemented. As well

as traditional BPM, SBPM allows efficiently man-

aging and coordinating business processes indepen-

dently from human resources. They are designed to

provide a support to the stakeholders involved in these

processes to answer the questions: what needs to be

done? When should it be done? These stakeholders

are assigned to perform tasks in specified sequences

without taking into consideration their acquired com-

petencies. Indeed, competencies management, which

has been suggested as a way to more effectively uti-

lize employee skills, stills not taken into consideration

while managing business processes. Thus, in this pa-

per we aim to answer how stakeholders can find the

right performers at the right time for the right type

of contribution. Our work is mainly based on three

phases: 1) identifying the required competencies to

fulfill a specific need. Based on a semantic analy-

sis, the system will be able to identify the required

competencies and automatically extract the possible

performers. 2) Then the identified performers will be

evaluated against our defined criteria (availability, co-

hesion, flexibility...) to select the relevant ones. 3)

Finally, after selecting the relevant performers, the

process model will be defined based on the identi-

fied skills. Therefore, processes could be designed,

modified and adjusted dynamically during execution

to include unplanned participants. In this paper, we

present our SBPM approach to support collaboration

during execution and designing processes on the fly.

So the remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 gives a depth review of BPM and the main

existing issues the roots of SBPM’s emergence. Then

Section 3 presents the suggested approach for effec-

tive and efficient SBPM improvement. And finally,

section 4 concludes the paper.

2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED

WORK

2.1 BPM

Business Process Management (BPM) is the dis-

cipline that combines knowledge from information

technology and knowledge from management sci-

ences and applies this to operational business pro-

cesses (Weske, 2012). The goal of BPM is to achieve

the organization’s objectives by aligning them with

business processes and to continuously improve these

processes. It includes concepts, methods, and tech-

niques to support the design, administration, configu-

ration, enactment and analysis of business processes

(Van der Aalst, 2007). BPM provides a platform to

manage business processes through their lifecycle as

it is depicted in Figure 1, which represents one of

the simplest proposed models of BPM’s lifecycle in

the literature. The technical tool to manage busi-

ness processes and support the entire lifecycle is Busi-

ness Process Management System (BPMS). Owing

to the complexity and turbulence of work environ-

ment, BPMS support the execution of stable and sim-

ple business processes. The need to support quick ad-

justment of business processes in order to meet chang-

ing environmental conditions was behind the devel-

opment of several approaches and suggestions in the

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

674

Figure 1: Van der Aalst’s BPM lifecycle.

literature. One from the best and newest way of sur-

vival and success of organizations is agility. Over the

last two decades, corporates have focused on improv-

ing the agility of their business processes. Several

solutions emerged today, to support processes agility

heavily influenced by context and application domain.

One of the recent solutions is Social BPM (SBPM)

mostly defined as the integration of Social Software

principles and techniques within BPM. The motiva-

tion for including social software and BPM contains

many facets: fostering collaboration, sharing knowl-

edge, support process models adaptation and others.

In fact, the aim of SBPM is to solve the principles is-

sues of traditional BPM, which will be revealed in the

next section.

2.2 BPM Principles Issues

The current state of traditional BPM has two princi-

pal issues identified by (Granitzer M. and Schmidt R.,

2010):”model reality divide” and ”lost innovations”.

• Model reality divide: it represents the gap be-

tween what the process actually is and what hap-

pens in real life. In fact, during the design stage of

BPM lifecycle, process models are created using

modeling languages like BPMN, Petri-nets and

others. Since these process models are often an

abstraction from the real world, exceptions are of-

ten not covered by them as well as tasks that are

difficult to be modeled.

• Innovation’s loss: during business process lifecy-

cle, the lack of model users’ implication leads to

lose some important ideas and information for in-

novation. BPM normally follows a top-down ap-

proach, where processes are designed by a group

of individuals and passed on to internal perform-

ers to follow (Sinur, 2011). Working under a strict

top down manner, employees are not motivated to

share ideas for process improvement and innova-

tion. Besides, their knowledge is either lost en-

tirely, or applied on the local scale of individual

process instances.

These properties of the standard BPM cycle make

it unsuitable for so-called knowledge-intensive pro-

cesses. These problems were behind the emergence

of SBPM.

2.3 Social BPM

Research in SBPM formally started in 2008 (Schmidt,

2009) and it has evolved ever since. Several defini-

tions have been proposed to understand what SBPM

is and how it operates. Although there is not a sin-

gle understanding of the concept of SBPM (Houy C.

and Loos P., 2011), depending on the specified needs,

SBPM could be adapted and its functionalities could

be integrated to satisfy these needs. Within BPM, so-

cial software principles can be used to support the

different lifecycle steps of a business process or to

support an individual lifecycle phase. In the litera-

ture, various works were carried out to well integrate

BPM and social software and to answer the research

question of how to overcome model-reality divide and

lost innovation principal issues of BPM. The first cat-

egory in SBPM is to support collaborative model-

ing of business process. Technical and non-technical

people have to participate in the discovery, modeling

and design of business processes in order to ensure

its acceptance. The first framework which is called

BPM4PEOPLE was developed by (Fraternali, 2012).

A social extension of BPMN known as BPMN 2.0

based on the use of design patterns is the principal fea-

ture of this framework. The extension made by (Fra-

ternali, 2012) aims to support collaboration among

stakeholders and to reduce model-reality-divide issue

using means of communication that will enable em-

ployees to exchange, talk about, integrate and lever-

age existing knowledge from different sources. In

(Hauder, 2014), they developed a solution based upon

hybrid wiki that empowers users to collaboratively

design and adapt information structures. Using hybrid

wiki, no special syntax or modeling concepts are re-

quired to utilize the structured information elements.

Another tool was presented by (Houy C. and Loos P.,

2011) called CoMoMod. This tool supports several

aspects of collaborative process modeling, such as si-

multaneous work of spatially distributed modelers on

one process model diagram. Socially support busi-

ness process during their execution phase is seldom

taken into account. Few approaches were developed

since the emergence of SBPM. One of these propo-

sitions is a framework called AGILIPO (AR., 2010).

AGILIPO follows the principles of agile software de-

velopment (Rosemann M., 2001) and of organiza-

tional design and engineering. An incomplete process

definition is specified by a set of activities that de-

scribe part, but not all, of the process instances behav-

A New Approach for SBPM based on Competencies Management

675

ior (AR., 2010). Another proposition to improve the

SBPM functionalities is developed by (Fettke, 2013).

This approach enables stakeholders to communicate

with each other, to create groups for discussions or

to ask question to the audience of a specific business

process. The given answers are not restricted to one

person rather they are visible to all members of the

created group. (Karakostas B., 2013) developed an-

other proposition that follows this idea. Their ap-

proach discusses how social tagging can be used in

the context of social business process management to

assist and support the execution of business processes

in a social environment. Even there are several ap-

proaches proposed in the literature to integrate social

software techniques within BPM, some problems re-

main unsolved. In many situations, a performer has

to improvise or to find the suited competencies to get

the work done. There are situations, where changes

on an existing process model are necessary, when ex-

ternal context of the process is changing. Although

the importance of competencies management none of

the proposed SBPM approaches supports this con-

cept. Offering BPM as social software is a promising

approach that fosters communication and collection

of knowledge by allowing multiple users to work on

the design, operation and improvement of a business

process simultaneously and without access control re-

strictions typical of traditional BPM (Karakostas B.,

2013). Enterprises have found it difficult to utilize

social software in such manner to 1) achieve its ob-

jectives, 2) add value and make it attractive to the

members and 3) avoid unintended consequences. Al-

though the importance of organizational integration

none of the proposed SBPM approaches support this

concept. Considering agility as the most important

aspect of processes management (Wafa Triaa, 2017),

SBPM needs to provide contextually useful informa-

tion, customized services connecting specific users to

each other in order to respond to subsequent process

exceptions. Lack of customization, community cre-

ation and expert’s retrieval process need to be studied

and implemented to better support and exploit SBPM

benefits. The accession of the required customized

information in real time is a crucial concept for a ro-

bust execution of business processes. Within actual

SBPM and even traditional BPM, information is not

classified, structured and organized; each actor can

express his or her opinion freely and give further sug-

gestions that need analysis before select the most rele-

vant ones. Instead of working alone, employees have

to establish and maintain relationships with one an-

other and to perform several interactions. We talk

about weak ties which are of special importance in

this context as they form the long tail of knowledge as

it is affirmed by (Schmidt, 2009). So leveraging the

collective intelligence of a business community can

only be accomplished if all relevant participants are

actually included and their needs considered. How

stakeholders can find the right actors at the right time

for the right type of contribution. To overcome this is-

sue, we think to support customized information dis-

tribution during run time. Actually, people cannot lo-

cate knowledgeable colleagues because they are not

provided with the proper means to do so. Based on

competencies retrieval process, employees can iden-

tify whom to talk and capture their knowledge effi-

ciently and easily. Our focus is to extend the reach

of SBPM for good inter organizational involvement

of employees during business process execution by

answering the following: how, when, and which ex-

ternal and internal actors should be included to per-

form processes activities? We also want to deal with

process actor autonomy as processes are often pre-

scriptive as the reality is mostly empirical and non-

determinist.

3 PROPOSED SBPM

FRAMEWORK

3.1 Functional Requirements

Our goal aims to analyze and construct the social net-

work between processes’ actors, to provide answers

to two important questions of ”who owns what?” and

”who needs what?” Owing to competencies retrieval

process and data mining techniques, unplanned par-

ticipations could be rapidly and dynamically taken

into account. To move forward the following areas

need to be investigated and addressed:

• Elimination of distinctions between designers and

executors in the SBPM framework. Executors

transmit the required information to complete the

process model. This is in order to avoid the typical

issue of model-reality divide as faced by current

approaches in BPM as well as SBPM.

• Merging of the design and execution phase in the

BPM model. So that there is no explicit or ordered

distinction between the two phases. Such ap-

proach will support agility of business processes.

• Elimination of pre-defined tasks in the processes,

in order to support knowledge intensive processes

characterized by activities that cannot be planned

easily. These processes may change on the fly

and are often driven by the contextual scenario in

which they are embedded in. The scenario dic-

tates who should be involved and who the right

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

676

person to execute a particular task is. The set of

users involved may be not formally defined and be

discovered as the process scenario unfolds.

• Identifying and exploiting competencies to op-

timize the choice of individual (or groups) for

emergent tasks. Relationships between the pro-

cess participants are mapped and measured within

social network analysis. One of its aims is

supporting collaboration in workplaces and team

building.

The above needs can be achieved through incorpo-

rating an approach where both design and execution

are blended, competency management is integrated

and social systems behavior is involved. Actors will

be identified due to their competencies to support pull

and push service. Therefore, we’ll support the cre-

ation of an organizational environment that enables

and fosters continuous customized contributions of all

stakeholders. The scenario dictates who should be

involved and who the right person to execute a par-

ticular task is. Therefore, the framework will sup-

port the design of a process during its execution (de-

sign by doing). Actually, one of the main basic pro-

cesses of competency management (Giuseppe Berio,

2006), (LeBoterf, 2004) is: competency utilization.

The aim of this process is to optimize the competency

allocation based on predefined human resources’ pro-

files. To better support the required-owned compe-

tency corresponding, performer’s profile should be

modeled. Without a clear sense of identity, there can

be no foundation for trust or reputation. Thus, when

using sufficient information about each performer’s

participation, each performer will have a specified

profile defined as a set of his owned competencies

facilitating the expert’s retrieval process. To do so,

we need to develop a competency referential to facil-

itate the identification of the required competencies

and the allocation of the acquired competencies. Now,

we will give some definition of the competency con-

cept and its main characteristics in the next section.

3.2 Competency Definition and

Characteristics

In industrial engineering competency is integrated as

an essential point of view for enterprise modeling. In

the literature, several definitions of competency are

available. For example in the HR-XML Consortium

Competencies Schema ((HR-XML, ), a competency

is defined as: A specific, identifiable, definable, and

measurable knowledge, skill, ability and/or other de-

ployment related characteristic (e.g. attitude, behav-

ior, physical ability) which a human resource may

possess and which is necessary for the performance

of an activity within a specific business context. There

are two main categories of competency derived from

the available literature, (SJanas, 2008), (Giuseppe Be-

rio, 2006):

• Hard competency: which refers to two types: a)

Know: It concerns everything that can be learned

from educational/formative systems. It represents

the theoretical understanding of something such

as a new or updated method or procedure, etcand

b) Know-how. It is related to personal experiences

and working conditions. It is learned by doing,

by practice and by experience. It is the practical

knowledge consisting in ”how to get something

done”.

• Soft competency: which consists on relational

know-whom, cognitive know-whom and behav-

ior. It is referred to individual characters, talents,

human traits, or qualities that drive someone to

act or react in a certain way under certain circum-

stances.

During our competency retrieval process, the aim is

firstly to identify what type of hard competency is

needed to reach/satisfy the goal. Thus, in our work,

we focus mainly on the first category of competency:

Hard competency. Many studies evaluate different

methods of competency modeling (Vernadat, 1999),

(Zarifian, 2001), (SJanas, 2008) show that ontology

have a greater expressiveness and meet better the re-

quirements and the goals of the competency model-

ing. Ontology are collections of concepts, instances

of concepts and relations among them that are ex-

pressed at the desired level of formality and that are

deemed to be important in characterizing the knowl-

edge domain under consideration at the desired level

of detail (Prilla, 2008). In our work, we have cho-

sen an ontological approach to define the function-

alities covered by the entreprise. In our ontology as

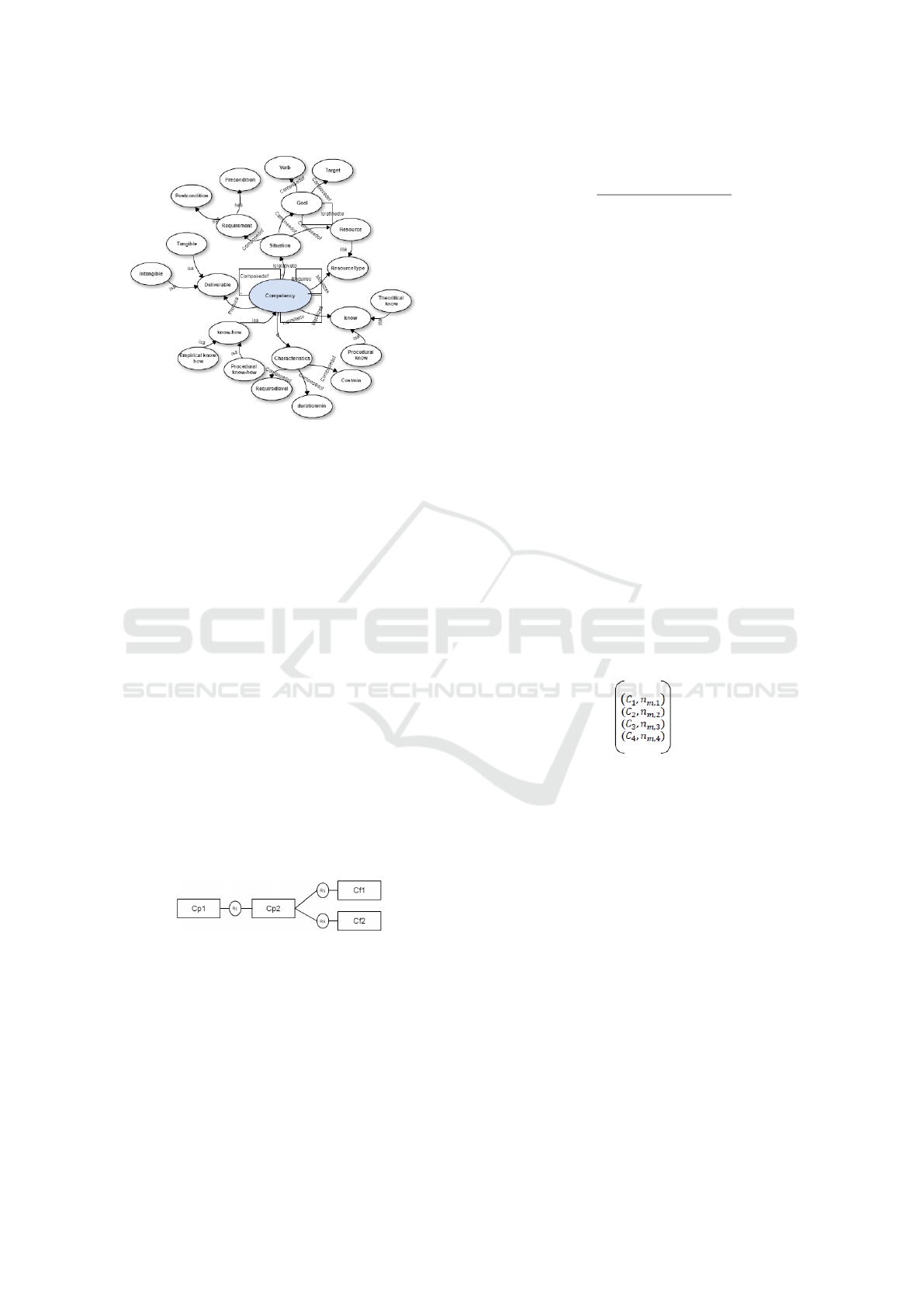

depicted in Figure 2, the central concept is ”Compe-

tency” which is linked to the five identified concepts:

Situation, Know-how, Know, ResourceType and De-

liverable. We propose that a competency manifests as

knowing how to act. It results in one or more knowl-

edge in action (Know how) in a given situation by

mobilizing knowledge (theories, procedures) and re-

sources (technologies, materials ) to provide a result.

The objective and the requirements of the correspond-

ing situation define the composition of the competen-

cies and specify the corresponding criteria for their

implementation. Possible relationships might exist

between two or more hard competencies. In some

cases, the execution of one competency requires the

presence of other one(s). Indeed, if a stakeholder

defines his goal in the form of a request, semantic

matching, which will be used to enable the identifi-

A New Approach for SBPM based on Competencies Management

677

Figure 2: Competency ontology.

cation of the required competency, will not be suffi-

cient if the relationships between them are not taken

into consideration. In this case, competency defini-

tion and modeling is supported by the relationship:

C

i

Requires C

j

where C

i

and C

j

are two hard compe-

tencies. Adding to that, symantic relations have been

defined to avoid the no recovery situation. We consid-

ered two types of ontological relationships: concep-

tual relations and semantic relations. A conceptual

relation is a relation between two concepts (ie ”pro-

duces” is a conceptual relation between the compe-

tency concept and the deliverable concept), where a

semantic relation is a relation between two names of

the same concept. (ie synonymy relation between two

names of the same competency: program in java ”is

a” develop in java). If we found different names for

the same concept, so we have to define a father con-

cept and the list of son concepts. We have defined the

relationships between the concepts of ontology as il-

lustrated in the Figure 3. The semantic relations exist

between the father concept and its son concept which

has the same meaning. Conceptual relations exist

only between two father concepts. When express-

Figure 3: Identified relations.

ing the need for the requestor through his request, the

extracted concept(s) can be directly aligned with the

competencies of our ontology or with other concept(s)

that are conceptually related to competency or seman-

tically related to another concept that is conceptually

related to one or more competencies. Each concept of

the stakeholder’s request will be randomly integrated

in the competency’s ontology and using the Dice mea-

sure as defined below, the corresponding concept will

be localized in the ontology.

Dice(C

r

, C

o

) =

2 ∗Card(C

r

∩C

o

)

Card(C

r

) +Card(C

o

)

right} (1)

The similarity values are real numbers between 0 and

1 where:

• Case 0.0: zero recovery.

• Case 1.0: Total recovery.

To match the concept of the request with the corre-

sponding one in the ontology, two situations are iden-

tified. On the first hand, the stakeholder could men-

tion the name of the required competency in his re-

quest, in such case the ontology is used to extend

the list of the required competencies with the similar

ones. On the other hand, the stakeholder may don’t

know what the required competency is. In this case

the ontology is used to (1) find the required compe-

tency and (2) extract the similar competencies if there

exist. Thus, a set of required competencies will be

identified which will be used to identify the relevant

performers.

3.3 Performer’s Profile

The profile of each performer is represented as a vec-

tor combing each acquired competency with the cor-

responding mastery level. Only father concepts are

used to define each performer’s profile. Where C

i

is

the index of competency i and n

mi

is the level of mas-

tery of competency i by the performer m. To evaluate

the acquired competency, we defined five levels ac-

cording to the French repository ROME (it provides a

simple description of competencies to be easily iden-

tified): (0: Absence), (0.25: Sensitization), (0.5: Ca-

pacity to put into practice), (0.75: Mastery) and (1:

Expertise). We have to note that the mastery level

is dynamic. It depends on two factors: learning (it

increases) and degradation (it decreases). According

to the available literature, the degradation of compe-

tency (respectively learning) depends on the number

of execution of the corresponding competency and the

period of interruption (respectively depends on the

number of execution and the learning ability of the

corresponding performer). As part of our approach,

the level of mastery is considered static but it is possi-

ble to take into account its dynamics in order to update

the repository of competency. To provide an efficient

access to relevant performer, we decide to present all

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

678

the identified profiles under the Galois approach. It

provides a formal and efficient classification process

to discover and represent hierarchies of concepts. It is

the basis of what is also called ”formal concept anal-

ysis”, mainly used in data analysis and knowledge ex-

traction. We chose to group all the profiles in the same

repository. In such case, the framework will sup-

port presenting performers with their owned assessed

competencies. The various defined performer’s pro-

file, presented in the form of competency’s vector,

will be aggregated. And due to an incremental struc-

turing algorithm, 1) competencies trellis will be con-

tinuously updated, and 2) possible candidates (per-

formers) to execute the set of required competencies

will be extracted. The result of using the Galois lat-

tice is a list of qualified competencies corresponding

to the required competency as shown in the following

picture: The reasons that prompt us towards the use

Figure 4: Result of using Galois Lattice.

of Galois Lattice are:

• It decomposes the context to characterize into

concepts (a set of performers with the same mas-

tered competencies). Indeed, every concept exists

in the lattice is a response to a query (search of

competencies). It gathers all actors mastering the

same competencies in a concept of Galois. It is

then easier to find for given competencies all cor-

responding performers.

• It is a dynamic method for concepts classification

where new concepts can be added to the lattice

or existing relationships between objects and their

properties can be modified. The profile of each ac-

tor is dynamic on two factors learning and degra-

dation. Indeed, the mastery level of the compe-

tence C

j

by the actor a

i

may increase or decrease

or actor a

i

can master a new competency.

• The relation in the Galois lattice classifies the

identified concepts (set of actors with set of

competences) in a decreasing or increasing way

(generalization or specialization). Indeed, while

browsing the lattice from bottom to top (inversely

from top to bottom), the number of the shared

competencies decreases and the number of actors

increases (conversely the number of competencies

increases and the number of actors decreases).

3.3.1 Basics of Galois Lattice

In this subsection, we briefly describe Galois lattices

(or concept lattices) and we give a basic overview of

the algebraic notions needed for our purposes. Ga-

lois lattices allow users to obtain every subset of in-

stances distinguishable according to the chosen at-

tributes. Further information, results and proofs may

be found in (M. Montjardet, 1970), (Birkhoff., 1973).

As input, we consider a non-binary relation between

a set of individuals and a set of attributes, in our case

a set of actors A and a set of keywords W of their ac-

quired competencies. A context is a triplet (A, C, R),

where R ⊆ A x C. R (a, c) means that the actor ”a”

has the competency c with a mastery level equals to R.

Using the relation R; we can derive each performer’s

profile (a set of keywords referring to all his/her ac-

quired competencies). Similarly, the set of perform-

ers mastering the same competency can be identified.

The basic idea of using Galois lattices is the partition

of data in a set of basic classes which are clusters of

instances sharing the same basic type (in our work

competency). The identification of the actors is done

using the following formula:

g(C) =

{

a ∈ A s.a ∀c ∈ C, R(a, c) ≥ α

}

(2)

Where α is the required mastery level to practice com-

petency C. This level as defined in the previous sec-

tion is between [0, 1]. Only actors, with acquired

mastery level above α, are selected. Actors, with

a mastery level below α, are considered as under-

competent and are not selected. To present the pro-

file of each actor, the set of his acquired competencies

with the corresponding mastery levels, we use the fol-

lowing expression:

f (A) =

{

c ∈ C s.a ∀a ∈ A, α = minR(a, c)

}

(3)

4 FURTHER SUGGESTIONS FOR

OUR APPROACH

Selecting the best performer depends on various at-

tributes from several dimensions: social, temporal,

business etc To socialize our framework and to opti-

mize its behavior with a high degree of positively af-

fecting stakeholders’ satisfaction, we add some func-

tionality. When looking at the time dimension, re-

garding the fuzzy nature of the only considered at-

tribute ”availability” (of performer and resources), to

trace it a need of a simple concept and easy to grasp

is recommended. A simple technique already used

with social applications (Facebook, twitter, Tumblr,

Google Plus) is adapted. Presence is about being able

A New Approach for SBPM based on Competencies Management

679

to share one’s availability status (online or offline)

so everyone is aware of it and can act accordingly.

Traceability of the status makes day-to-day allocation

easier. The social dimension typically focuses on the

cohesion of the group and the closeness between the

stakeholder and the performer(s). While selecting the

relevant performer(s) two cases should be taken into

consideration: 1) all owned competencies from one

performer correspond to the required ones, in this case

this candidate is adequate to satisfy the goal. Another

case, one performer has less than the required com-

petencies. Thus, team could be constructed based on

”cohesion” criteria and in this case soft competency is

taken into consideration. Overall, closeness between

stakeholder and selected performer(s) offered the best

combination of speed and efficiency; in general, the

more closed the network, the more misbehavior will

be detected and a significant benefit on problem solv-

ing will be offered. Regarding the cost dimension,

the costs of executing a competency may be fixed

or depend on the type of used resources. In our re-

search, we are focused on cost of used resources to

practice the required competencies. Costs related to

human resources are out of the scope of our research.

To reduce the level of uncertainty prevalent in this

type of decision-making (selection of the relevant per-

former(s)) a multi-criteria approach will be adopted

for the purpose of this step. Subsequent to the given

brief description of the identified attributes, to rapidly

and dynamically take into consideration unplanned

participations the following requirements need to be

investigated:

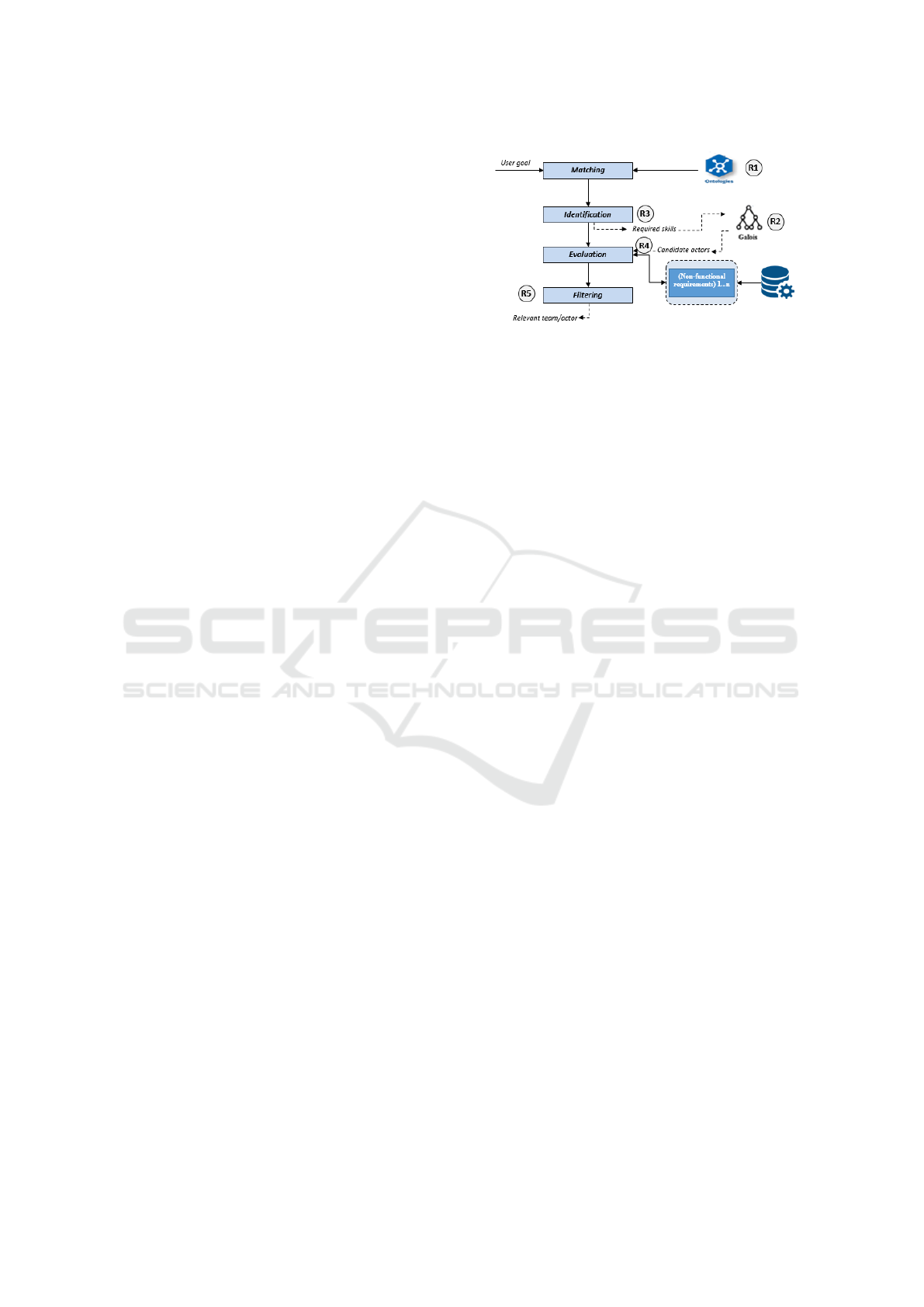

• R1: Identification and assessment of performer

owned competencies

• R2: Presentation of each performer with his

owned assessed competencies

• R3: Allowing goal and required competencies

correspondence

• R4: Allowing required and owned competencies

match

• R5: Selection of the relevant performer according

to context dependent criteria to make a personal-

ized service.

Each defined goal will provide the intention behind

the needed competencies to be performed. Once the

goal is defined and analyzed the corresponding re-

quired competencies will be identified. All these

identified requirements are classified into three main

steps as shown in Figure 6: Analysis, Identification

and then Selection. As a last step of our framework,

the process’s model will be adjusted according to the

identified competencies. As defined in our ontology,

Figure 5: Proposed framework.

the concept competency exhibits an intentionality for-

mulated by the goal (which characterizes the situation

of using the competency). Using each competency

goal and corresponding relations, processes could be

designed, modified and adjusted dynamically during

execution in order to include unplanned participa-

tions.

5 CONCLUSION

In this article we discussed the problem of traditional

BPM approaches. These approaches suffered from

several issues and a lot of works have been made

in order to support BPM and improve their agility.

Lastly, social software has been used to support the

different lifecycle steps leading to the emergence of

SBPM. Current SBPM approaches present their own

challenges and problems that first need to be over-

come. Our study shows that these approaches espe-

cially support the design phase of business processes

while the execution phase is seldom taken into ac-

count. In that way, knowledge intensive processes

still not supported. In our work, we aim to support

running processes which can be adapted during exe-

cution to include unplanned participants and complete

the work more effectively. We presented a framework

for SBPM using competencies management and so-

cial network features to support emergent processes

and find rapidly the relevant performers. Our frame-

work is mainly based on competency (required and

owned competency) and the context in which they can

be practiced. Effective and automated competency

management creates a real time and predictive inven-

tory of the capability of any workforce. It is more

than ever a primordial factor for many companies to

better assess their human capital, to plan the execution

of emerged tasks, to tackle highly innovative projects.

Performer’s selection requires a careful examination

of various attributes. Two aspects evaluate the benefit:

tangible and intangible. Tangible benefit includes en-

gendered cost; we are focused on material resources

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

680

used to practice the required competencies. Intangible

benefits may include social relationship with stake-

holder, availability status of performers and required

resources, the cohesion of the selected performers if

there is not possible performer able to reach the goal.

As a future work, required techniques to support Eval-

uation and Filtering steps of our framework will be

defined and the proposed framework will be proto-

typed and evaluated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Region Auvergne

Rhone-Alpes for financial support of this research

work.

REFERENCES

AR., Meziani, R. M. R. M. D. A. A. F. N. S. (2010). Ag-

ilipo: Embedding social software features into busi-

ness process tools. In Proceedings of BPM 2009

International Workshops (pp. 219-230). Germany:

Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Birkhoff., G. (1973). Lattice theory. In American Mathe-

matical Society Colloquium Publications.

Fettke, P., L. P. V. (2013). Organizational and technologi-

cal options for business process management from the

perspective of web 2.0. In Business and Information

Systems Engineering 2(1) 1528.

Fraternali, p., M. (2012). Combining social web and

bpm for improving enterprise performances. the

bpm4people approach to social bpm. In Proceed-

ings of the 21st international conference companion

on World Wide Web (pp. 223-226). New York: ACM

Publishers.

G., Dengler, F. J. B. K. R. N. S. P. M. S. M. S. R. S. B.

(2011). Key challenges for enabling agile bpm with

social software.

Gilbert (2010). The next decade of bpm.

Giuseppe Berio, Franois B. Vernadat, M. H. (2006). Analy-

sis and modeling of individual competencies: Toward

better management of human resources.

Gottanka, M. (2012). Modelasyougo: Design of sbpm pro-

cess models during execution time.

Granitzer M., Happ S., J. S. J. M. J. P. K. A. N. S. R. D. and

Schmidt R., S. E. (2010). Combining bpm and social

software: Contradiction or chance?

Hauder, M. (2014). Bridging the gap between social soft-

ware and business process management:. In A Re-

search Agenda.

Houy C., F. P. and Loos P., D. (2011). Collaborative busi-

ness process modeling with comomod. In Interna-

tional Workshops on Enabling Technologies.

HR-XML. Consortium competencies schema. In

http://www.hr-xml.org/.

Karakostas B., M. R. (2013). Goal-driven social business

process management. In science and information con-

ference. pages 894901. IEEE.

LeBoterf (2004). construire les comptences individuelles et

collectives : les rponses 90 questions. 3eme edition,

Editions dOrganisation.

M. Montjardet, M. B. (1970). Key challenges for enabling

agile bpm with social software.ordre et classification,

alg‘ebre et combinatoire 2. In Hachette Universite,.

Palmer, N. (2011). The role of trust and reputation in social

bpm.

Prilla, M. (2008). Semantic integration of process mod-

els into knowledge management: A social tagging ap-

proach. In Proceedings of 11th International Confer-

ence on Business Information Systems (pp.130 141).

Austria: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Rosemann M., Uthmann C., J. B. (2001). Guidelines of

business process modeling. In vol. 1806 of Lec-

ture Notes in Computer Science, Springer Verlag, pp.

3049.

Ryan., K. S. S. L. E. W. (2009). Business process manage-

ment (bpm) standards: a survey.

Schmidt, N. (2009). Bpm and social software.

Sinur, J. (2011). Social bpm: Design by doing. In Gartner.

SJanas (2008). Choosing the right method to assess and rate

competencies in your organization. In Aug 27th 2008,

Competency Management.

Vernadat, F. (1999). Techniques de modlisation en en-

treprise : application aux processus oprationnels. In

Economica.

Wafa Triaa, Lilia Gzara, H. V. (2017). Exploring the influ-

ence of social software on business process manage-

ment. In IFAC, Toulouse.

Weske (2012). Business process management - concepts,

languages, architectures.

Zarifian, P. (2001). Le modle de la comptence. ditions Li-

aisons, Paris.

A New Approach for SBPM based on Competencies Management

681