Development of an Online Learning Platform for University

Pedagogical Studies-Case Study

Samuli Laato, Heidi Salmento and Mari Murtonen

Department of Educational Sciences, University of Turku, Turku, Finland

Keywords: Higher Education, Learning Platform, Distance Education, Online Teaching, Staff Development.

Abstract: Due to a high demand of university pedagogical staff development courses in our university, we were faced

with the problem of not being able to offer university pedagogy courses for everyone who wanted to study

them. Additionally, we wanted to seek ways to improve our already existing teaching. As a solution, we

created a web based learning platform called UTUPS (University pedagogical support). The platform allows

us to reach a wider audience and offer courses more conveniently to our teaching staff. Since the platform

was released in Autumn 2015, offered modules have been completed cumulatively over 300 times. We

propose a learning environment like UTUPS can significantly increase the flexibility and scale of studies that

a university can offer. We will provide a thorough explanation on why and how the environment was made,

a technical description of the current UTUPS platform, compared it to already existing solutions and analyse

its strengths and weaknesses. In order to evaluate the platform, we will utilize primarily student feedback and

refer to literature and existing solutions when relevant.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the demand for greater amount and

more flexible staff development courses, called the

university pedagogy courses in our university, has

increased. The University of Turku offers 10, 15 and

35, together 60 credits (ECTS) courses for those staff

members, who can show that they have teaching at

the university. Thus, we have not been able to accept

those researchers and doctoral students, who do not

teach at the university at the time they apply. Also, in

many years, we have not been able to take in all

teachers (who currently have teaching) willing to

participate in pedagogical courses due to high amount

of applicants. Therefore, we have been searching for

a solution to offer more courses for a wider student

group, including researchers and doctoral students,

with a relatively small funding. The situation is quite

similar in other smaller Finnish universities, so we

have been searching for cooperation possibilities with

the other universities.

In 2015, the University of Turku made a decision

to fund a development project named UTUPS to

create a learning platform for university pedagogical

courses that would be open to all university staff and

doctoral students for self-study and also offer some

courses to earn credit points. During 2015-2017 the

University of Turku Pedagogical Support, UTUPS,

was created, tested and consolidated in use. In the

beginning of 2017, the Finnish Ministry of Education

and Culture assigned a funding to a project called

University Pedagogical Support, UNIPS, to create a

platform in cooperation with 8 Finnish universities,

based on the previous UTUPS platform.

The UTUPS platform was built and designed

specifically for the purpose of distributing university

pedagogical material and knowledge, and it was

never intended to be a platform for, for example,

providing solely SPOC or MOOC courses. The aim

of this paper is to introduce the reader to the UTUPS

learning solution by analysing the basic principles of

the pedagogical and technical solutions, and

presenting results from the testing of the

environment. We will also set some visions for the

future, especially concerning our new UNIPS

developmental project.

2 PEDAGOGICAL SOLUTIONS

FOR UTUPS

When designing the UTUPS system, our focus was

on producing high quality online material on higher

education and providing an easy access for our staff

Laato, S., Salmento, H. and Murtonen, M.

Development of an Online Learning Platform for University Pedagogical Studies-Case Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0006700804810488

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 481-488

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

481

members to that material, so they can obtain

information through self-study on any university

pedagogical topic of their choosing that is available

on the platform, in order to support their teaching.

Our secondary focus was to incorporate guided study

with credit points in our system, which in addition to

using the self-study materials, would utilize online

teamwork for collaborative improvement on

pedagogical skill. Additional goals we wanted to

address with our solution included the possibility to

offer university pedagogy courses to our doctoral

students, to create an environment for flexible

studying, to create smaller sets of university

pedagogy studies than previously and to enable the

option of developing disciplinary specific courses.

The university pedagogical material on the

website was designed with a focus on making the

material engaging and entertaining, as well as being

informative. In practise this meant that the videos on

the website were purposefully short, and that quizzes

and other interactive elements were added when

relevant. The purpose of these interactive elements is

to activate the learner, as well as mediate information.

The more specific content of the university

pedagogical material on the website is out of the

scope of this paper, but we will refer to 3 pilot

modules “Becoming a teacher”, “Lecturing and

expertise” and “How to plan my teaching” in this

paper, in order to demonstrate some design decisions

we have made, and when we evaluate our platform.

The 3 pilot modules are a way to categorise the

material on the platform. This makes it easier for our

staff members to find information on the specific

topic they desire. The division of the pilot material

into 3 modules not only helps in finding information,

but also acts as a division into 1 credit (ECTS)

courses, referred to as guided study. The guided study

modules are all divided into two parts: an individual

task period and a small group working period. The

individual task period consists of going through the

study materials on a specific module, and writing an

essay based on those materials.

The small group working phase supports the

pedagogical principle of creating knowledge and

developing pedagogical expertise in collaboration

(Hakkarainen, 2015). By selecting groups that have

participants on different skill level, e.g. experienced

teachers and more novice doctoral students, we can

enhance the collaborative benefits of the group

working.

In small group working, the students will set

questions to each other and comment each other’s

texts, which will give them a possibility to reflect

their own thinking and help each other to develop

more elaborated conceptions. The more experienced

members of the group can share their teaching

experiences with the more novice ones and the

novices can ask advice from the more experience

ones. The members can also share feelings and solve

problems together. The goal is to enhance conceptual

development and change (Vosniadou 2013; Chi,

2017; Vosniadou, 2008; Vosniadou 2014; Chi, 2014;

Chi, 2009) , i.e. to help students to build their teaching

expertise through getting familiar to educational

concepts and discussing about those.

3 OUR TECHNICAL SOLUTION

AND WAYS TO STUDY IN

UNIPS

In the implementation of a new learning platform, the

design decisions previously made are constantly

evaluated, or alternatively evaluated in iterative

cycles. According to Hevner design science

methodology, both the knowledge base and the

environment effect design decisions. The feedback

from our students provided suggestions to improve

the platform from the environment side, and existing

similar solutions like Moodle or Coursera gave us an

example from the knowledge base side on how to deal

with certain problems. The UNIPS environment was

mostly based on the pedagogical goals discussed in

chapter 2 of this paper. The technical implementation

began in March 2015 and was ready in autumn 2015

for preliminary testing. Only minor revisions have

since been made to the core system, as the feedback

has been positive. However, we seek to constantly

evaluate and improve our platform. In this chapter we

will go through the current technical implementation

and design of the UTUPS environment. (Hevner,

2007).

3.1 UTUPS Compared to SPOCs and

MOOCs

When looking at already existing solutions that would

suit our needs, SPOCSs (Small Private Online

Courses) and MOOCs (Massive Open Online

Courses) need to be discussed. The University of

Phoenix launched an online campus with courses

covering entire bachelors and master’s degrees

already in 1989. Since then, online courses have

become increasingly popular over the recent years

with the introduction of (SPOCs) and (MOOCs). The

first time the term MOOC was used, was by Dave

Cormier in 2008, and is now a common term used to

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

482

describe perhaps the most popular form of online

teaching, and SPOC’s emerged roughly around the

same time as MOOC’s. The difference between the

two is, that MOOC’s are, as the name states, offered

for a wide audience through platforms like Coursera,

[4] where as SPOC’s are private and usually offered

only inside Universities. From now on we will set our

focus on SPOCs, as they share more characteristics

with our UTUPS solution than MOOC’s, since the

UTUPS modules can be completed in SPOC -style

with a guided study. (Kaplan 2016).

Even if SPOC’s are sometimes easily transferable

to MOOC courses, they have various different

characteristics. Kaplan et al (2016) list two types of

SPOCS: asynchronous and synchronous. An

asynchronous SPOC can be completed by students on

their own schedule, without the need to be present at

any specific times. However, also an asynchronous

SPOC can set deadlines for the students. On the other

hand a synchronous SPOC requires real time

participation from the students.

The UTUPS solution uses both the asynchronous

and synchronous solutions. One guiding principle in

developing the UTUPS solution was the idea that the

platform is always open for our staff and doctoral

students for self-study. The materials are always

available and there are instructions how to study the

materials. This can be done whenever the students

want to. However, our university also wants to offer

pedagogical studies where students can earn credit

points, so we offer the courses also in synchronous

way. It includes the same tasks as the self-study

mode, but adds a collaborative small group working

phase in the digital environment.

Stracke (2017) argues that high dropout rates are

essential in MOOCs and online courses, because the

costs of accepting extra students to these courses for

the course organiser are very low, or even close to

non-existent, and on the other hand some students

might only come to the courses to take a peek of what

the course actually contains. The UTUPS

environment embraces this idea, by offering the

course materials to all staff members at all times

without even the need to enrol to the modules for a

guided study. As the UTUPS material is constantly

available for all staff members to view and study, the

dropout rates for the actual guided studies can be

decreased. (Stracke 2017).

3.2 Technical Decisions in the

Development of Our Platform

Firstly, the decision between hosting an intranet

solution and an internet solution had to be made. The

main problem regarding having the solution built on

our universities intranet was the scalability. In case

we wanted to share the course materials at some point

with people outside our university, we would have

needed to expand to an internet website in any case.

Therefore we decided to create a new password

protected webpage for UTUPS, and reserved the

domain utupedasupport.utu.net for the purpose.

UTUPS environment was built on top of

WordPress CMS, which was chosen because it is a

widely used open source system that offers powerful

tools for quick standard website development. In our

WordPress site we could add video material, links to

course articles, simple tasks that had automated

checking, as well as various other interactive and non-

interactive elements. We used the Tesseract -theme,

and a collection of freely available plugins, our own

pictures and videos to come up with our websites

visual appearance.

A great emphasis was put on the usability of the

website. We wanted the modules containing the

actual study materials to be right on the front page,

one click away when entering the website. Also the

study material of one module was all put on their own

separate pages, so that all the information related to a

specific topic would be in one place. The only

exception being the scientific papers that were linked

on the module page and part of the material are

located elsewhere due to legal reasons. Figure 1

shows the front page of our website. Below the site

logo, menus and banner picture there are links to the

modules and some motivational videos for the

students.

Figure 1: The main page of the UTUPS website.

Following the principle of good usability and

modern stimulating design, we tried to make the place

the materials on the website in a creative, but clear

way. Figure 2 demonstrates how instead of simply

listing video materials on the website, we decided to

superimpose them on top of a picture. This kind of

design has resulted in a positive feedback from our

users. More detailed analysis of student feedback is

presented in chapter 4.

Development of an Online Learning Platform for University Pedagogical Studies-Case Study

483

Figure 2: Video materials placed on top of a picture in the

module “Becoming the teacher”.

The website is currently hidden from non-

authorized visitors with Ben Husons “Password

Protected” Wordpress plugin, which asks for a

password from any user who enters the website.

However, we are looking to add the SAML based

Shibboleth -login of our University federation to the

website. This way we would be able to obtain more

accurate data for research by identifying the students

visiting the website. Additionally this would allow us

to monitor and control better who has access to the

website and its materials.

3.3 How UTUPS Works in Practise

In order to test the platform in a form of offering

courses where students can earn credit points, one

pilot module was created. The pilot module was

named as “How to plan my teaching” and it was tested

in late 2015. The module was divided in two parts: a

self-study period, when students individually read

given materials and watched the videos in the

environments, as well as did other interactive tests or

task in the environment, and to the second period of

small group working.

When the first module was evaluated and good

results were obtained, two more modules were

created. All 3 pilot modules were divided into two

parts: a self-study period and a teamwork period. The

two other modules were “Becoming a teacher” and

“Lecturing and expertise”.

In the self-study period, which is the same to all

students whether they will pursue for credits or not,

we wanted to be able to offer our students videos,

selected scientific articles and possibly additional

simple tasks and interactive exercises. An example of

an additional interactive exercise would be a quiz,

where the student would automatically receive the

result of the test, telling him or her what kind of a

teacher he or she most likely is. This quiz is based on

the ATI, Approaches to Teaching Inventory by

Trigwell and Prosser (2004), but used as a self-testing

questionnaire it should be used with caution. Thus,

the students are informed that this is a playful quiz

that should not be taken too seriously and the

theoretical basis of the inventory is dealt in the

literature of that module.

In addition, students may participate in creating

word clouds and other interactive materials together.

The words clouds have been concentrating on some

specific topics or videos, where student have been

able to comment how they understand the topic or

what is related to it. The idea of these interactive

elements is to enrich the learning environment with

activating tasks, which help the student focus on

learning. Additionally the interactive exercises can be

used to, for example, demonstrate pedagogical

concepts and raise the student’s awareness of his or

her own teaching.

For the technical implementation of the teamwork

period, which is for those who seek to obtain credit

points by completing guided study modules, we

required a platform that enabled the students to

communicate with each other in a sensible way, and

collaboratively edit each other’s texts in order to

engage in collaborative information forming. After

exploring the possibilities of integrating this to our

website, we decided not to reinvent the wheel, and

chose Moodle (Dougiamas, 2003) as an additional

technology to support our system. However, some

exercises planned in the pilot modules required

collaborative editing, which at the time was not

available in Moodle. Therefore, for the purpose of

allowing collaborative editing and discussions as part

of our study modules, we adopted the use of google

docs (Spaeth, 2012) in our course platform.

In the teamwork period, the students are divided

to groups of four. Their task is to read each other’s

essays which they wrote in the individual study phase,

and then comment on each other’s works. By this

way, discussion is encouraged and the students can

both reflect their ideas together as well as built their

knowledge and pedagogical expertise in

collaboration with their colleagues.

There is a tutor on the course whose task is not to

guide discussions or participate in those, but to look

that every group is active and that the discussions and

comments are in line with the course goals, i.e. that

there are no discussions that concern some irrelevant

topics for the course or that are somehow harmful. In

case that more funding would be available, a tutor

who would guide the discussions would also be

beneficial for the group discussions.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

484

4 EVALUATION AND ANALYSIS

OF THE UTUPS

ENVIRONMENT

The three pilot modules: becoming a teacher,

lecturing and expertise and how to plan my teaching

have been completed 112, 120 and 112 times

respectively. The first modules were organised in

autumn 2015, and the last ones counted in this

number were completed in spring 2017. A successful

completion is counted, if the student completed all

required individual and group tasks in the module.

14,9% of all who completed the modules were

university staff members, 64,3% doctoral students

without teaching responsibilities, and 20,8% were

doctoral students who currently had teaching duties at

the university. All together 154 individuals have

completed at least one module through the UTUPS

environment. Most students studied more than one

module.

4.1 Student Feedback

In order to evaluate how well the UTUPS platform

works, we asked students to send feedback and

answer questions regarding the platform after

completing UTUPS guided study modules. Student

feedback data was collected over three instances. The

first data is from spring 2016, where we received

replies from 27 students. The next feedback

collection is from autumn 2016, where only 9

students participated by sending feedback. Another

feedback collection form was sent in autumn 2016,

where we received additional 21 replies. All together

we have obtained feedback from 57 students, which

is roughly 30% from all individuals who have

completed one or several modules in the UTUPS

environment. We will analyse the first feedback

session in greater detail, and provide shorter

descriptions of the two following feedback

collections.

Figure 3: Distribution of which modules students studied in

the feedback collected in spring 2016.

In spring 2016 we asked the students 5 questions after

they had completed one or more UTUPS modules.

Overall 27 students replied. From Figure 3 we notice

that the module “How to plan my teaching” was the

most popular of the 3 offered modules with 20

students completing the module, while the

“Becoming a Teacher” module was the least popular,

and was completed by 14 students. From other

instances where the modules have been organized, the

numbers have varied.

Figure 4: Did the individual task period support your

learning?

We asked the students 5 questions, which were:

1. Did the individual task support your

learning?

2. What do you generally think about the

individual tasks, would you change them

somehow?

3. Did the teamwork period support your

learning?

4. What do you generally think about the

teamwork tasks, would you change them

somehow?

5. General feedback, comments or

suggestions? Let us know how we can

improve UTUPS environment and the

modules. We are thankful for all kind of

feedback.

In figure 4 we see that an overwhelming majority

of 26 students out of 27 replied that they felt the

individual task period supported their learning. We

also asked the students verbal feedback of how they

would improve the individual task period. To analyse

the replies, we singled out all improvement

suggestions, and came up with how many students

suggested them. 3 students wished the video materials

in the course Lecturing and Expertise were shorter.

They found it difficult to search for specific

information in 15min long educational videos, and

said it would have been easier to have the same

material in text form. 4 students said the modules

contained too much work in relation to the amount of

student credits received from completing them.

Similarly to the feedback from the individual task

period, we analysed the replies we got concerning the

teamwork period by identifying improvement

suggestions received from the students. Figure 5

shows that generally the students also enjoyed the

teamwork periods of the modules, like they enjoyed

the individual tasks. 3 students said the teamwork

Development of an Online Learning Platform for University Pedagogical Studies-Case Study

485

Figure 5: Did the teamwork period support your learning?

period needed more time than 2 weeks. Only 3

students said the conversations emerging between the

students were not helpful for their learning, but that

otherwise they enjoyed the teamwork period.

Additionally, only2 students stated that having to

jump between the UTUPS website, our universities

Moodle page and Google Docs document was

annoying, and that if possible, all tasks should be

integrated under one single environment. Thus we

can conclude that the environment worked well, the

working load was reasonable and the teamwork

period supported students’ learning.

Finally we received 20 replies in our final

question asking general feedback of our solution.

Here the students gave very positive feedback, but

there was criticism by 2 students towards the video

material being hard to follow compared to traditional

lectures, and additionally the tight schedule of the

courses, and too big of a workload compared to the

student credits received, was also addressed.

4.2 UTUPS Website Activity

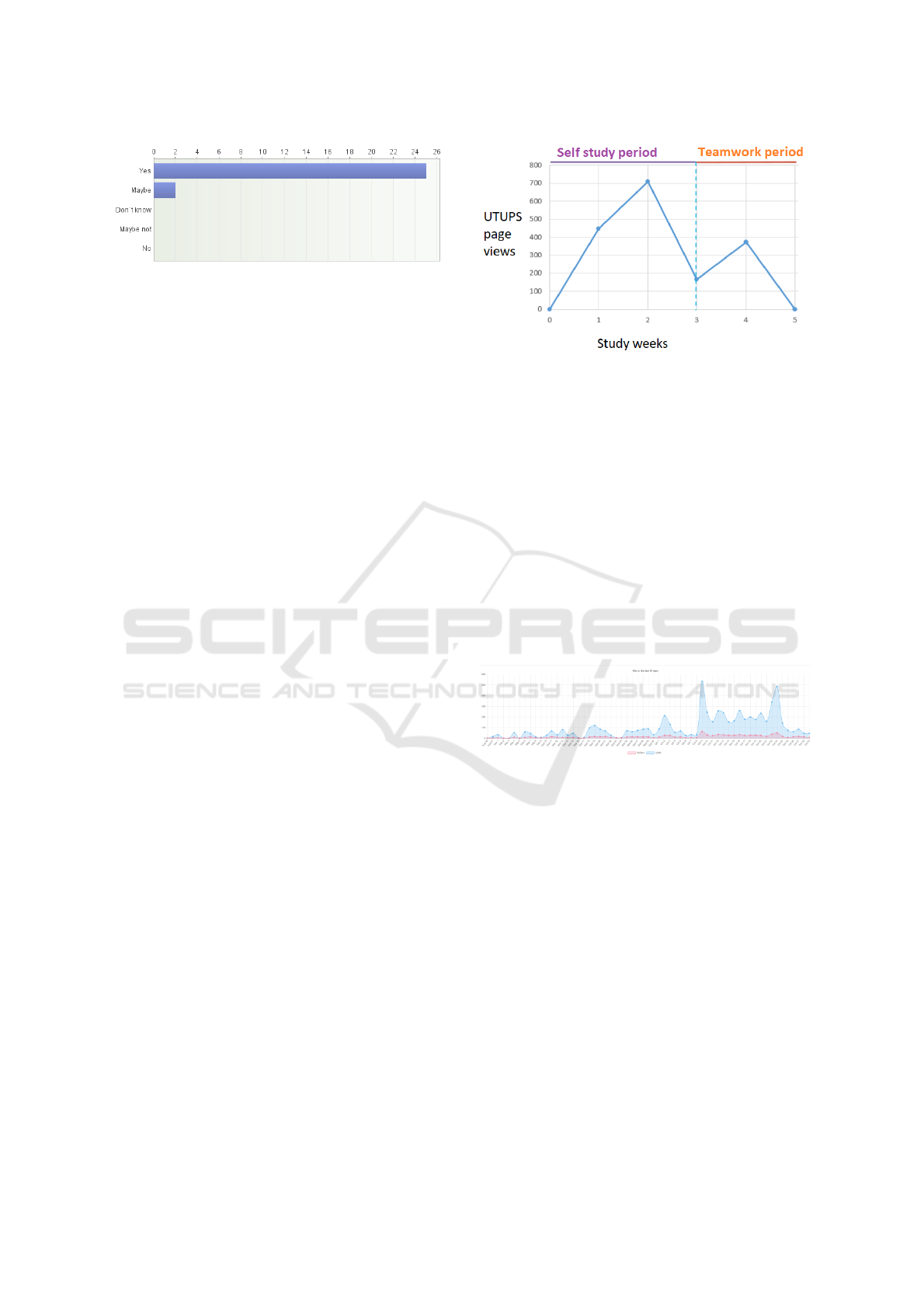

One way to analyse the UTUPS materials is to look at

website statistics from our platforms webpage. We

used WP statistics -WordPress plugin and Google

Analytics -WordPress plugin to obtain information on

how many unique visitors entered the website and

when, what materials did they use and so on. Figure

6 shows the evolution of website traffic during the

second pilot module phase in early 2016. This data is

cumulatively collected from the three password

protected modules, in order to clear the data from

random visitors. As expected, there was a peak on the

website traffic on the final week of the self-study

period, when the individual task deadlines

approached. Which was interesting however was, that

even in the teamwork period where students did not

necessarily need to refer to the course materials to

pass the exercises, there was still notable traffic on the

site.

In addition to following the website traffic during

guided studies, we wanted to know if students still use

the materials when they are not completing a guided

study. To do this, we observed data from our website

Figure 6: UTUPS platform traffic during the second pilot

module.

during the last 60 days. Figure 7 shows this data

plotted. The y axis presents the amount of visitors and

the x-axis is the time of 60 days. The two biggest

peaks in the graph are the moments when the guided

study period began, and the last two days before

individual task essay due date. From the data we can

observe that indeed the website is regularly utilized

by a few students, but primarily it is used during the

guided study periods. Additional researched is

required to identify whether the teaching staff in our

university has purposefully looked up knowledge

from the website to support their teaching, or if they

have come to the webpage only out of curiosity or

other reasons.

Figure 7: UTUPS platform traffic before and during a

guided study period.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

The guided study modules have been completed

cumulatively over 300 times in our environment and

the student feedback of the system has been positive.

Therefore we can conclude that the UTUPS platform

is a welcome addition in our University ecosystem, as

a medium for offering university pedagogical

courses. Additionally, the UTUPS materials that are

now available for all teaching staff at all times, is a

resource that has been previously unavailable for

teachers in our university, at such convenience.

Naturally in addition to the UTUPS environment, our

university still offers traditional pedagogical courses

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

486

that include contact teaching, as well as the possibility

to borrow literature to support the teachers’

pedagogical understanding.

With the success of the UTUPS environment,

funding was applied for its continued development

and extension to other Finnish universities. In early

2017, the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture

gave funding to build a new system (titled UNIPS) for

8 Finnish partner Universities, based on the UTUPS

solution. The project is funded until 2020 and it

covers the costs of the technical development of the

platform and the creation of several new modules and

materials, and research of the solution.

The new UNIPS environment will share the same

pedagogical principles as UTUPS. It will be hosted

online, and the webpage will have password

authentication for those partner University staff

members who want to study the materials. What

separates it from SPOCs and MOOCs is that the main

priority in the website is to have categorised high

quality university pedagogical materials available,

and only the secondary goal is to offer guided studies

for those who want to get credits or certificates for

studying the materials.

In the becoming UNIPS solution of 8 universities,

each university will provide other universities with

materials for at least one module. The modules are,

however, developed in cooperation, i.e., in addition to

the university that is responsible for the module, there

will be at least two other universities participating in

the planning and developing of the module. The

individual partner universities will be locally

responsible for offering the guided studies with credit

points for their own students, but all content creators

will offer example guidelines to other universities on

how to organise them. These instructions will include,

for example, tips how to organise groups, what kind

of ideas can be evolved in the group discussions and

what would be the pitfalls to avoid in each module.

The choice not to include automatic evaluation

was made, because the created modules include

teamwork sessions and essays as ways to study, and

with current technology it is not possible to evaluate

an essay or group processes automatically with

sufficient quality. Yet, the platform allows the use of

interactive tasks which give immediate feedback to

the user. Additionally, some modules might be

constructed in the future so that all tasks are

automatically assessed. This is another thing we will

look into as we develop the UNIPS platform.

Another goal for the environment, which we will

keep in mind in the future, is the development and

offering of disciplinary specific courses. This has not

yet been realised, but the platform provides an

opportunity for that and we hope that in the future it

will be utilised in a way that gives teachers

possibilities to develop and organise courses on

specific disciplines or topics. Further work is also

needed in organising and assessing the disciplinary

specific courses on our website.

The UTUPS and the upcoming UNIPS solutions

have thus far been proven to be effective, well-liked

and cost-efficient in offering university pedagogical

staff development courses for university teacher,

other staff and doctoral students. The platforms will

be further developed on the principles described

above and new solutions will also be searched for.

REFERENCES

Chi, M. T. H. (2009). Active-contructive-interactive: a

conceptual framework for differentiating learning

activities. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1, 73-105.

Chi, M. T. H., Kang, S., & Yaghmourian, D. L. (2017).

Why students learn more from dialogue- than

monologue-videos: Analyses of peer interactions.

Journal of the Learning Sciences, 26, 10-50.

Chi, M. T. H., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP

framework: Linking cognitive engagement to

active learning outcomes. Educational

Psychologist, 49, 219-243.

Christensen, G., Steinmetz, A., Alcorn, B., Bennett, A.,

Woods, D., & Emanuel, E. J. (2013). The MOOC

phenomenon: Who takes massive open online courses

and why?

Combéfis, S., Bibal, A., & Van Roy, P. (2014).

Recasting a Traditional Course into a MOOC by

Means of a SPOC. Proceedings of the European

MOOCs Stakeholders Summit, 205- 208.

Dougiamas, M., & Taylor, P. (2003). Moodle: Using

learning communities to create an open source

course management system.

Hakkarainen, K. & Palonen, T. & Paavola, S. &

Lehtinen, E. (2004) Communities of networked

expertise: Professional and educational perspectives.

Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Hevner, A. R. (2007). A three cycle view of design

science research. Scandinavian journal of

information systems, 19(2), 4.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2016). Higher

education and the digital revolution: About MOOCs,

SPOCs, social media, and the Cookie Monster.

Business Horizons, 59(4), 441-450.

Parpala, A., Lindblom‐ Ylänne, S., Komulainen, E.,

Litmanen, T., & Hirsto, L. (2010). Students'

approaches to learning and their experiences of

the teaching–learning environment in different

disciplines. British Journal of Educational

Psychology, 80(2), 269-282.

Spaeth, A. D., & Black, R. S. (2012). Google Docs as a

form of collaborative learning.

Development of an Online Learning Platform for University Pedagogical Studies-Case Study

487

Stracke Christian M, Why We Need High Drop-Out

Rates in MOOCs: New Evaluation and

Personalization Strategies for the Quality of

Open Education, 2017 IEEE 17th International

Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies

(ICALT).

Trigwell, K. & Prosser, M. (2004) Development and use

of the approaches to teaching inventory.

Educational Psychology Review 16:4, 409– 424.

Vosniadou, S. (2013) Conceptual change in learning and

instruction: The framework approach. In S. Vosniadou

(auth.) International handbook of research on

conceptual change. New York: Routledge 9–30.

Vosniadou, S. & Vamvakoussi, X. & Skopeliti, I.

(2008) The framework theory approach to the

problem of conceptual change. Teoksessa S.

Vosniadou (editor.) International handbook of

research on conceptual change. New York:

Routledge.

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

488