Improving Students’ Performace Through Gamification:

A User Study

Natalia Nehring, Nilufar Baghaei and Simon Dacey

Department of Computer Science, Unitec Institute of Technology, Private Bag 92025, Auckland 1142, New Zealand

Keywords: Gamification, PeerWise, Performance, Motivation, Tertiary Education, Active Learning.

Abstract: Lack of motivation is an issue for some learners. If they do not find the course materials engaging, they do

not spend enough time to gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter. The term gamification is used to

denote the application of game mechanisms in non-gaming environments with the objective of enhancing the

process. Gamification has been shown to be an effective and motivating technique for enhancing students’

learning outcome. In this paper, we evaluate the effectiveness of a web-based gamified tool (PeerWise) in

enhancing tertiary students’ performance doing a Computer Science degree at Unitec Institute of Technology.

PeerWise allows students to actively participate in a subject by authoring their own questions and answering,

commenting on and rating other students’ questions. Results of an evaluation study conducted over 11 weeks

(n = 180) showed that using the tool (both voluntary and compulsory) improved students’ performance and

they found it valuable for their learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

The term gamification is used to denote the

application of game mechanisms in non-gaming

environments with the objective of enhancing the

process enacted (Deterding et al., 2011a and Nacke,

2011). Gamification is related to pre-existing

concepts such as serious games, playful interaction

and game-based technologies (Deterding et al., 2011b

O'Hara, and Dixon, 2011). Gamification, in an

educational context, can be applied at elementary

education, lifelong education, and higher education

levels.

Some learners drop out of study and/or achieve

poor results due to lack of motivation (Fan and

Wolters, 2014) and the low engagement with the

content (Yang, 2013). Gamification has been shown

to increase learners’ engagement with course

materials and improve their motivation, learning

participation and collaboration (Angelova, 2015;

Dicheva et al., 2015). Gamification has potential, but

a lot of effort is required in the design and

implementation of the experience for it to be fully

motivating for participants (Domínguez et al., 2013).

PeerWise, https://peerwise.cs.auckland.ac.nz/,

(Denny et al., 2008b 2008a, 2008b) is a freely

available gamified badge-base achievement tool. It

allows students to author multiple-choice questions

based on their understanding of the subject, and

answer, comment on and rate other students’

questions, thus supporting active learning (Bonwell,

1991), curiosity, creativity, problem solving and

collaboration. Students get more points and badges by

creating and explaining their understanding of course

related assessment questions, and by answering and

discussing questions created by their peers. PeerWise

provides students with a reputation score, which is an

approximate measure of the value of student’s

contributions to others and it gradually increases over

time. The individual components of the one’s score

are based on the questions they have posted, their

answers to questions and their evaluations. A user’s

reputation score will only increase when other

students agree with, or endorse his/her contributions.

PeerWise has been reported to stimulate a profound

learning and to improve students’ performance

(Denny et al., 2008a and Luxton-Reilly, 2010; Danny,

2015).

In this paper, we investigate the effect of

compulsory vs voluntary use of a web-based gamified

tool on students’ learning outcome in a computer

science course. The research questions we are

investigating are: 1) Will using a gamified tool in a

CS course improve the learning outcome of our

students? 2) Is there any correlation between using

Nehring, N., Baghaei, N. and Dacey, S.

Improving Students’ Performace Through Gamification: A User Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0006687402130218

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 213-218

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

213

PeerWise throughout the semester and the course

formal assessments’ results? 3) Is there any difference

in learning outcome, if course marks are allocated to

PeerWise contribution? 4) What is the students’

perception of having a gamified tool embedded in

their study? The rest of the paper is organised as

follows. Section 2 gives an overview of recent

literature. Section 3 presents the methodology and

Section 4 reports our initial findings. Section 5

concludes the paper and highlights future research

opportunities.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Currently students are digital natives and they have a

different profile. They grew up with digital

technologies and have different learning styles, new

attitude to the learning process and higher

requirements for teaching and learning (Kiryakova et

al., 2014).

Some reviews of the literature available have

already been carried out: Gamification in education:

A Systematic Mapping Study (Dicheva et al., 2015

and Angelova, 2015), A systematic mapping on

gamification applied to education (de Sousa Borges

et al., 2014 and Isotani, 2014) and Gamification and

education (Caponetto et al., 2014 2014). Research

objectives in gamification articles can be categorised

into behavioural change, challenging the students,

engagement, improving learning, mastering skills,

producing guidelines and encouraging socialisation

(de Sousa Borges et al., 2014).

Gamification, in an educational context, can be

applied at elementary education, lifelong education,

and higher education levels. In a practitioner’s guide

to gamification of education (Huang and Soman,

2013) outline a five step process 1) understanding the

target audience and the context, 2) defining the

learning objectives, 3) studying the experience, 4)

identifying the resources, and 5) applying

gamification elements. When considering

gamification some key criteria to be considered are

the duration of the learning program, the location of

the learning (for example: classroom, home, or

office), the nature of the learning programme (for

example one-on-one or group), and size of class (or

size of groups) (Huang and Soman, 2013).

It is also important to define what the lecturer

wants the student to accomplish by completing the

learning program. Specific learning goals can include

the students understanding a concept, being able to

perform a specific task, or being able to complete the

learning programme (Huang and Soman, 2013).

Olsson et al. (2015) pointed that in virtual learning

environment users usually feel lonely and puzzled in

their learning journey, therefore visualization and

gamification may be applied as solutions, but the

former worked better than the latter. It is suggested

that the effects of gamification are worth studying

more deeply and widely on various learning styles.

Urh et al. (2015) analysed the use of gamification in

e-Learning process, including its advantages and

disadvantages, and argued that there were

possibilities of practice gamification in higher

education. They stated that the application of

gamification was designed to meet project objectives,

thus different types of education would affect the

system development as well as different learning

styles and personalities of learners. De-Marcos et al.

(2014) conducted a test on the effects of using both

social networking and gamification into an

undergraduate e-Learning course. The results show

that they work well for practical learning but not for

gaining knowledge. Although learners’ attitude

towards study has been improved, their participation

and achievement are still low, which is not in line

with the assumption that gamification will boost the

learning effects. The reasons lying under are worth

investigating.

Swacha and Baszuro (2013) proposed an open-

source e-Learning platform for computer

programming education with gamification concepts

and methods. The system takes into account both

personal engagement and team collaboration,

however, its operability and effectiveness are still to

be tested in a real learning environment. Bitonto et al.

(2014) presented UBICARE system integrated with

gamification mechanism for training and learning

purposes, playing the role of improving engagement

and interaction. The long-term effects require

ongoing research. Osipov et al. (2015), after

investigating the effects of gamification, find out that

the people with shy personalities don’t benefit much

since they don’t like to collaborate with others. Gene

et al. (2014) describe a gamification framework

integrated with Massive Online Open Course

(MOOC), the purpose of which was to decrease

learners’ drop-off rate through motivation and

collaboration inspiration. The competition from

ranking rating, team work from voluntary activity,

and the social networking from publishing the

number of “Likes” together with course progress and

certification gamification elements towards the

higher achievement rate of MOOC course. It has

proved to be able to play a very good role in

promoting learners’ motivation and cooperation;

however, they pointed out the real effects of

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

214

gamification on the quality of learning should be

investigated through comparing it with traditional

learning process.

One difference between game-based learning

(GBL) and gamification is that in GBL learners are

playing to learn while gamification is to incentivize

learners to learn, which makes game-based learning

appear more interesting and engaging (Baghaei et al.,

2016; Plass et al., 2015). An analysis of game-based

learning and gamification applications in university

environment (Cózar-Gutiérrez and Sáez-López,

2016) describes that game-based learning is

perceived to improve learners’ engagements and

active participation while gamification works better

for interaction and collaboration. In our earlier work,

we investigated whether introducing weekly quizzes

improved final mark for the students (Nehring et al.,

2017). In this study, we are investigating another type

of active learning components, i.e. students

participating in writing questions on weekly topic by

using a gamified web tool and the effect on enhancing

their learning.

3 METHOD

An evaluation study was conducted over 11 weeks

period with 180 tertiary students aged 19-29 at Unitec

Institute of Technology. The participants were

studying a second-year course on Web Design and

Development. They were randomly allocated to three

groups. The control group (n = 64) did not have

access to PeerWise. First experimental group (n = 55)

had voluntary participation (VP) and second

experimental group (n = 61) had compulsory

participation (CP), meaning 2.5% of total grade had

been allocated to their PeerWise contribution.

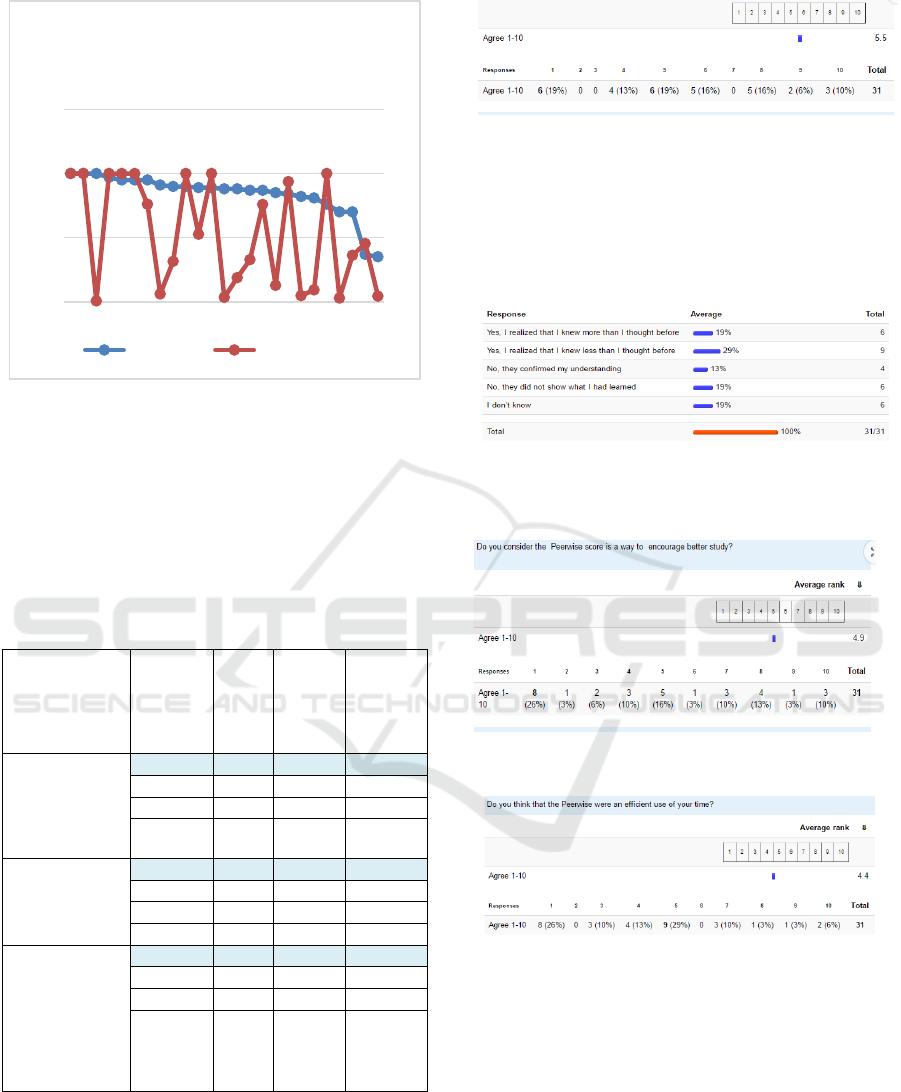

Figure 1: PeerWise statistics on our experimental groups:

voluntary participation (VP) at the top and compulsory

participation with (2.5%) mark allocated (CP).

The PeerWise dashboard for our course is shown

in Figure 1. It contains information about number of

participants, number of questions created, number of

answers, number of comments and a date of last

answer. PeerWise activity was introduced in week

one. Each student was asked to contribute minimum

of one question per week.

A subjective evaluation was also conducted to

find out what students think about PeerWise.

Questions about the user experience were developed

and are listed below:

1. Do you believe that participation in PeerWise

affect your study habits?

2. Did the participation in PeerWise affect your

understanding of how much you knew or how

much you had learned about the IWD course?

3. Did you find it stressful to do the PeerWise

question(s)?

4. Were your study habits affected by the existence

of the PeerWise or your results on them?

5. Do you consider the PeerWise score is a way to

encourage better study?

6. Do you think that the spending time on PeerWise

was an efficient use of your time?

4 RESULTS

In voluntary participation group (VP) 37 students out

55 decided to participate. As shown in Figure 1, The

VP group created 96 questions compared with 199

questions created by the CP group. The CP group

submitted 3657 answers compared with 1085

submitted by the VP group and the number of

comments was 5 times more compared with the VP

group.

Our hypothesis was that there is a correlation

between PeerWise contribution and the formal

assessment’s marks and that it would help predict

student’s results. The initial results show that there is

no correlation and the score on PeerWise activity can

only predict results for 50% of students. We believe

one reason for this is because the marks allocated to

PeerWise activity is small and some students ignore

it all together.

The semester is currently in progress and we only

obtained results for the first formal assessment and

compared the groups, as shown in Table 1. The results

for the PeerWise participants’ marks show that the

average scores are higher than the non-participants’

marks. The average mark on first formal assessment

is 72.2 for the control group, compared with 77.8 for

the VP group and 78.5 for the CP group.

Improving Students’ Performace Through Gamification: A User Study

215

Figure 2: Correlation between PeerWise score and formal

assessment marks.

We also looked at the course assessment marks for

students actively contributing to PeerWise and

students not participating. Their mark is 84.4 in

average for the first formal assessment compared with

73.7, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Average marks on formal assessments for different

groups.

Groups

Assessment

All

PeerWise

Not

participated

Conrol group

without

PeerWise

access (n=64)

1

72.2

N/A

N/A

2

76.2

N/A

N/A

3

83.7

N/A

N/A

Final

73.1

N/A

N/A

Voluntary

participation

(VP) (n=55)

(PW37)

1

77.8

79.8

70.7

2

82.1

83

74.6

3

82.9

83

68.9

Final

76.5

79.3

70.7

Compulsory

participation

with course

mark 2.5%

assigned,

(n=61)

(PW52)

1

78.5

84.4

73.7

2

N/A

N/A

N/A

3

N/A

N/A

N/A

Final

N/A

N/A

N/A

The subjective evaluation survey was done in

week 10. 31 participants chose to take part in this

exercise. About half of the students believed that

participation in PeerWise on a weekly basis improved

their study habit (see Figure 3). The average answer

is 5.5 out of 10.

Figure 3. Response to “Do you believe that participation in

PeerWise affect your study habit?”.

In response to question 1 (“Did the participation

in PeerWise affect your understanding of how much

you knew or how much you had learned about IWD

course”), the results show that 29% said they know

less, and 19% found that they know more. (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Response to “Did the participation in PeerWise

affect your understanding of how much you knew or how

much you had learned about IWD course?”.

Figure 5: Response to “Do you consider the PeerWise score

is a way to encourage to better study?”.

Figure 6: Response to “Do you think that the PeerWise were

an efficient use of your time?”.

5 CONCLUSION & FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we investigated the effect of

compulsory vs voluntary use of a web-based gamified

tool on students’ learning outcome in a second-year

computer science (web design and development)

course. We uncovered several interesting

observations. The preliminary results show that the

0

50

100

150

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25

Comparison Project 1

Marks and Participation in

PeerWise

Project 1 Participation

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

216

individual reputation scores on PeerWise was not

correlated with the average formal assessment results.

There was improved performance for both

experimental groups (VP and CP) who contributed to

PeerWise, with more noticeable improvement for the

students who actively participated. The CP group

who had 2.5 course marks allocated to PeerWise

contribution authored, commented on and responded

to significantly more questions than the VP group and

did slightly better in the formal assessment.

Subjective evaluation showed that half of the

participants liked contributing to PeerWise and found

it valuable for their learning.

More studies are needed to examine the

effectiveness of gamification on students’

performance and enjoyment throughout the entire

semester. We plan to analyse the difficulty level of

students’ questions and its correlation with students’

achievement level. We will look at further analysing

the user interaction data logged on PeerWise, which

would allow us to gauge the extent to which the

gamification process successfully embeds enjoyable

experiences and meaningful learning outcomes.

Analysis of the interaction data as well as conducting

a series of interviews with participants will also allow

us to think in terms of what motivates a student to

interact with a web-based gamified tool and how that

motivation can be sustained over time. We plan to

study the effectiveness of different gamification

features on long-term behavioural changes,

motivation level and increased knowledge of

participants and propose a set of design guidelines.

We believe our research paves the way for the

systematic design and development of full-fledged

gamified tools in the context of education.

REFERENCES

Baghaei, N., Nandigam, D., Casey, J., Direito, A., and

Maddison, R., 2016. Diabetic Mario: Designing and

Evaluating Mobile Games for Diabetes Education.

Games for Health Journal: Research, Development,

and Clinical Applications, 5(4).

Bonwell, C. C. E., and James A., 1991. Active Learning:

Creating Excitement in the Classroom. ASHE-ERIC

Higher Education Reports.

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED336049

Caponetto, I., Earp, J. and Ott, M., 2014. Gamification and

education: A literature review. In European

Conference on Games Based Learning, Academic

Conferences International Limited, 50.

de Sousa Borges, S., Durelli, V. H., Reis, H. M. and Isotani,

S., 2014. A systematic mapping on gamification

applied to education. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual

ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, 2014. ACM,

216-222.

Cózar-Gutiérrez, R. and Sáez-López, J.M., 2016. Game-

based learning and gamification in initial teacher

training in the social sciences: an experiment with

Minecraft. International Journal of Educational

Technology in Higher Education, 13(1), p.2.

De-Marcos, L., Domínguez, A., Saenz-de-Navarrete, J. and

Pagés, C., 2014. An empirical study comparing

gamification and social networking on e-

learning. Computers & Education, 75, pp.82-91.

Denny, P., 2013. The effect of virtual achievements on

student engagement. Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Paris, France: ACM.

Denny, P., 2015. Generating Practice Questions as a

Preparation Strategy for Introductory Programming

Exams. Proceedings of the 46th ACM Technical

Symposium on Computer Science Education. Kansas

City, Missouri, USA: ACM.

Denny, P., Luxton-Reilly, A. and Hamer, J., 2008a. The

PeerWise system of student contributed assessment

questions. Proceedings of the tenth conference on

Australasian computing education - Volume 78.

Wollongong, NSW, Australia: Australian Computer

Society, Inc.

Denny, P., Luxton-Reilly, A. and Hamer, J., 2008b. Student

use of the PeerWise system. SIGCSE Bull., 40, 73-77.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R. and Nacke, L., 2011a.

From game design elements to gamefulness: defining

gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th international

academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future

media environments, 2011a. ACM, 9-15.

Deterding, S., Sicart, M., Nacke, L., O'Hara, K. and Dixon,

D., 2011b. Gamification. using game-design elements

in non-gaming contexts. In CHI'11 extended abstracts

on human factors in computing systems, 2011b. ACM,

2425-2428.

Di Bitonto, P., Corriero, N., Pesare, E., Rossano, V. and

Roselli, T., 2014. Training and learning in e-health

using the gamification approach: the trainer interaction.

In International Conference on Universal Access in

Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 228-237). Springer,

Cham.

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G. and Angelova, G., 2015.

Gamification in education: a systematic mapping study.

Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18, 75.

Domínguez, A., Saenz-de-Navarrete, J., de-Marcos, L.,

Fernández-Sanz, L., Pagés, C. and Martínez-Herráiz, J.-

J., 2013. Gamifying learning experiences: Practical

implications and outcomes. Computers & Education,

63, 380-392.

Fan, W. and Wolters, C.A., 2014. School motivation and

high school dropout: The mediating role of educational

expectation. British Journal of Educational

Psychology, 84(1), pp.22-39.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K.,

Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H. and Wenderoth, M. P., 2014.

Active learning increases student performance in

Improving Students’ Performace Through Gamification: A User Study

217

science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 8410-8415.

Gené, O.B., Núñez, M.M. and Blanco, Á.F., 2014.

Gamification in MOOC: challenges, opportunities and

proposals for advancing MOOC model. In Proceedings

of the Second International Conference on

Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing

Multiculturality (pp. 215-220). ACM.

Huang, W. H.-Y. and Soman, D., 2013. Gamification of

education. Research Report Series: Behavioural

Economics in Action, Rotman School of Management,

University of Toronto.

Kiryakova, G., Angelova, N. and Yordanova, L., 2014.

Gamification in education. In Proceedings of 9th

International Balkan Education and Science

Conference.

Nehring, N., Dacey, S. and Baghaei, N., 2017. Providing

Regular Assessments and Earlier Feedback on Moodle

in an Introductory Computer Science Course: A User

Study. In Proceedings of 25

th

International Conference

on Computers in Education (ICCE'17), Christchurch,

New Zealand, December 4-8.

Olsson, M., Mozelius, P. and Collin, J., 2015. Visualisation

and Gamification of e-Learning and Programming

Education. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 13(6),

pp.441-454.

Osipov, I.V., Nikulchev, E., Volinsky, A.A. and Prasikova,

A.Y., 2015. Study of gamification effectiveness in

online e-learning systems. International Journal of

advanced computer science and applications, 6(2),

pp.71-77.

Plass, J.L., Homer, B.D. and Kinzer, C.K., 2015.

Foundations of game-based learning. Educational

Psychologist, 50(4), pp.258-283.

Prince, M. 2004. Does active learning work? A review of

the research. Journal of engineering education, 93,

223-231.

Swacha, J. and Baszuro, P. 2013. Gamification-based e-

learning platform for computer programming

education. In X World Conference on Computers in

Education (pp. 122-130).

Urh, M., Vukovic, G. and Jereb, E., 2015. The model for

introduction of gamification into e-learning in higher

education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 197, pp.388-397.

Yang, D., Sinha, T., Adamson, D. and Rosé, C.P., 2013.

Turn on, tune in, drop out: Anticipating student

dropouts in massive open online courses.

In Proceedings of the 2013 NIPS Data-driven

education workshop (Vol. 11, p. 14).

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

218