Wear It or Fear It

Exploration of Drivers & Barriers in Smartwatch Acceptance by Senior Citizens

Sima Ipakchian Askari

1

, Alina Huldtgren

2

and Wijnand IJsselsteijn

1

1

School of Innovation Science, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

2

Department of Media, University of Applied Sciences D

¨

usseldorf, D

¨

usseldorf, Germany

Keywords:

Smartwatches, Seniors, Technology Acceptance, Wearables, Assistive Technology.

Abstract:

The number of people with an age above 65 is increasing, and many live longer. Most seniors prefer to stay

at their own home. Within the area of ambient assisted living (AAL) technology solutions have been aimed

to assist seniors in the challenges that can arise when wanting to live independently. However, technology

acceptance has been rather low, also due to stigmatization when using assistive systems. New technologies,

such as the smartwatch, which is unobtrusive and not recognized as an assistive device by outsiders, have the

potential to improve the autonomy and independence of seniors. This research aims to investigate the potential

barriers and drivers of smartwatch use by seniors, by means of conducting a diary study and interviews. Results

showed that the acceptance of the smartwatch depended mainly on the usability, interest and added value of

the smartwatch. Additionally, the findings indicate that changes to the smartwatch need to be made in order to

address the barriers that are found, and to ultimately enhance acceptance.

1 INTRODUCTION

We are witnessing a phenomenon that is called “dou-

ble greying”, i.e. the number of people with an age

above 65 is increasing and these people also live lon-

ger lives (Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid, 2017).

In the period of 2008-2013 the number of Dutch ci-

tizens above 65 increased with almost 400 thousand

(van Duin, 2007). Not all these seniors are capable

of living on their own. In 2014, ca. 140.000 seni-

ors above 65 lived in a nursing home or rehabilitation

center. The living conditions in nursing homes are

not always optimal, in 2015 51% of the residents and

nurses of nursing homes had the feeling that there was

not enough time to take care of the residents. 61% of

them felt that there was not enough time to give resi-

dents personal attention (Ouderenfonds, 2017). Over-

all, most seniors prefer to stay at their own home

as long as possible (Rijksoverheid, 2016). However,

the desire for independence bears challenges as well.

Many seniors, have to deal with multiple health is-

sues as they grow older, e.g. declining vision, labored

walking and lower endurance (GGZ Drenthe, 2013).

Moreover, more than 260.000 people in the Nether-

lands suffer from dementia, in 2050 it is expected that

this number will increase towards half a million. Furt-

hermore, the number of Dutch citizens above 65 who

have died due to a fatal fall has continued to increase

in the past years (Ouderenfonds, 2017). Technology

has the potential to improve the lives of seniors. Un-

der the umbrella term ‘ambient assisted living’ several

technologies, including sensors (either on the person

or in the environment) and ICT, are employed to as-

sist seniors in their life by providing necessary infor-

mation or required services (Abrahao et al., 2014).

They enable monitoring of home appliances (smart

home), monitoring diets, reminding seniors of ap-

pointments and medication schedules (Chappell and

Zimmer, 1999). A new technology that can be pro-

grammed to fulfill these functions is the smartwatch–a

wearable device with computational power that can

be worn around the wrist. It can be connected to ot-

her devices through wireless connection, alert users

through notifications and can also collect and store

personal data through the wide range of sensors that

are embedded in the watch (Cecchinato et al., 2015).

Currently, the smartwatch is aimed as a generic we-

arable consumer electronics product. At the same

time, the smartwatch bears the potential to signifi-

cantly support seniors in their daily live due to the

many functionalities that the smartwatch can support

like activity tracker, fall detection, or medication plan

follow up etc. As a result of this, a smartwatch could

improve the autonomy and independence of the se-

26

Ipakchian Askari, S., Huldtgren, A. and IJsselsteijn, W.

Wear It or Fear It.

DOI: 10.5220/0006673000260036

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2018), pages 26-36

ISBN: 978-989-758-299-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

nior, making it possible for a senior to stay in their

own home, instead of having to live in a care home

(Fuchsberger, 2008). Additionally, because the smart-

watch is a consumer product and not designed spe-

cifically as an assistive device, stigmatization is low

and, thus, seniors may accept it more easily. Howe-

ver, the potential of the smartwatch to support seniors

in their daily live has not been fully explored and stu-

died yet. Focusing on user acceptance is an important

factor in the success of new technologies (Nickerson,

1981; Gould et al., 1991). Therefore, we explored

the barriers and drivers of acceptance of smartwatches

for seniors through qualitative interviews and a diary

study.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Obstacles for Seniors when using IT

In order for new technologies to be successful it is im-

portant to focus on user acceptance (Nickerson, 1981;

Gould et al., 1991). The technology acceptance mo-

del (TAM) can be used to understand the rationale of

why users accept or reject an information technology

(IT). According to the TAM model, the perceived use-

fulness and perceived ease of use of the technology

are the two important factors determining whether a

person may or may not use the system (Legris et al.,

2003). While the TAM model is focused on the accep-

tance of IT and can be applied to all user groups, the

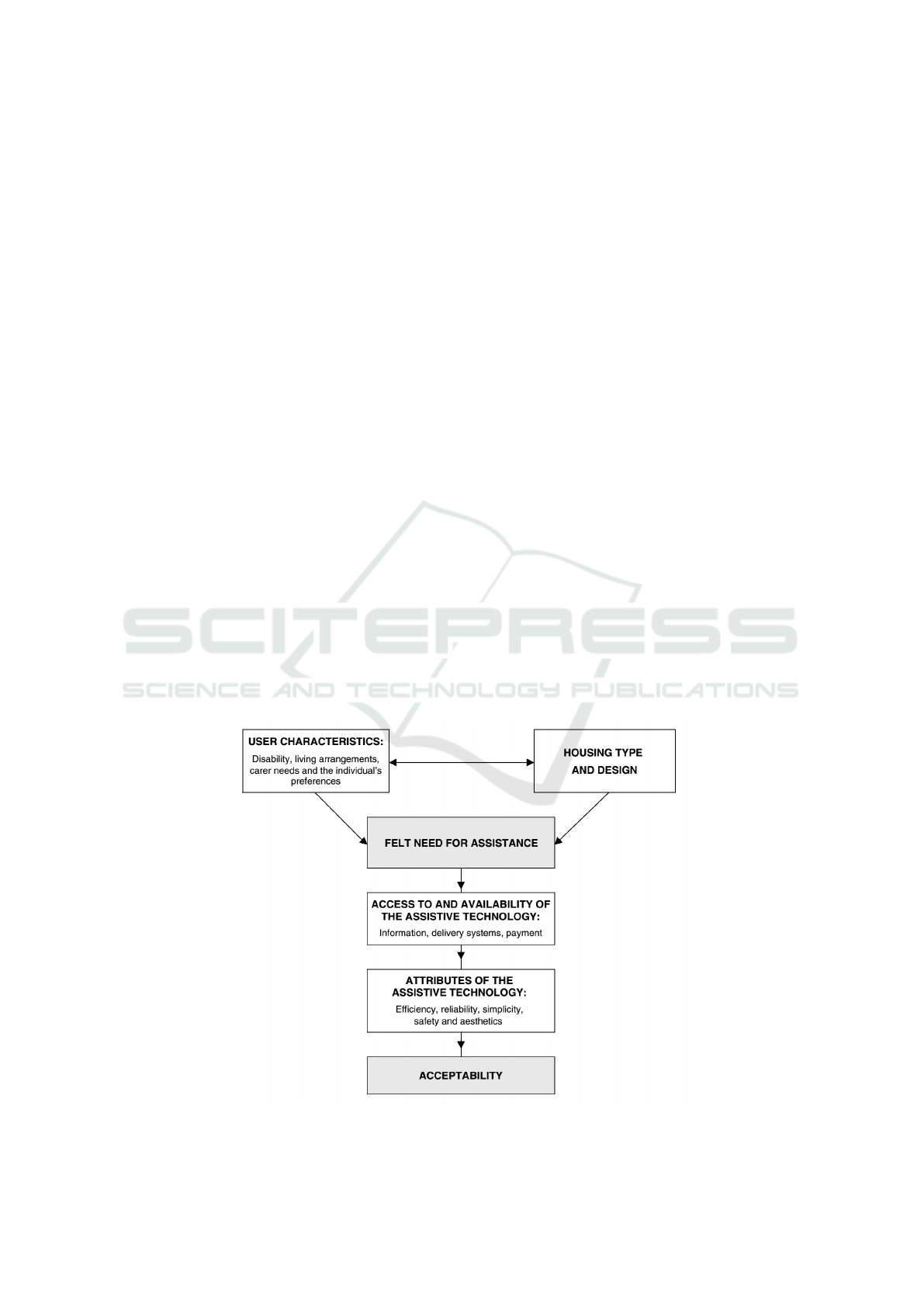

model developed by McCreadie and Tinker (2005),

as illustrated in Figure 1, is focused specifically on

the acceptability of assistive technologies by seniors.

According to this model the acceptability of assistive

technologies depends on the following factors:

• The Need for Assistance by the Senior. This is

affected by disabilities of the senior, their living

arrangements, preferences and caregiver needs.

• Access to and Availability of Technology. This

entails whether the senior could afford the techno-

logy and if the senior has information about the

technology.

• Acceptability. This is dependent on the attributes

of the assistive technology, such as the efficiency,

reliability, simplicity, safety and aesthetics.

As described in the model of McCreadie and Tinker

(2005) the need for assistance plays an important role

in acceptance of assistive technology. According to a

prior study (Portet et al., 2013) some of the frequently

expressed needs by seniors are: security, the ability to

monitor their health, the use of proactive systems, sy-

stems with good usability, confidence in being able to

use the systems, privacy and the use of voice inter-

faces. Unfortunately, in many cases technologies are

developed without seniors in mind (Czaja and Lee,

2007). This often results in interfaces or systems with

a low user-friendliness for seniors. Consequently, se-

niors can encounter difficulties when using the device

(Demiris et al., 2004). An additional factor is, that

seniors encounter difficulties when learning how to

Figure 1: Model for acceptability of assistive technology (McCreadie and Tinker, 2005).

Wear It or Fear It

27

use a new system, due to their declining learning ca-

pacity (Czaja and Lee, 2007). The older seniors get,

the harder it is for them to comprehend context and

to recall and learn new information. Furthermore, se-

niors might experience a level of stress and anxiety,

related to low self-efficacy when using technology; a

sense they do not have the capabilities to use a new

technology. This feeling increases when receiving ne-

gative feedback and/or feedback that is not fully un-

derstood (e.g., error messages) (Czaja and Lee, 2007;

Nap et al., 2013). It has also been observed that the re-

covery time of seniors, after making an error is higher

compared to younger people. Moreover, they tend to

become more anxious when tasks get more complica-

ted (Gudur et al., 2009). Besides anxiety surrounding

low technology self-efficacy and the challenges of le-

arning a new system, other age-related declines such

as vision loss and diminished motor skills can result in

barriers, when using new technologies (Yang, 2008;

Becker, 2004).

2.2 Potential Drivers of Smartwatch

Use

As smartwatches have only recently become availa-

ble on the consumer market, research surrounding dri-

vers and barriers of smartwatch use by senior citizens

is very limited. Moreover, research on the topic of

smartwatches in general is also scarce. One of the

few studies in this area (Boletsis et al., 2015) was con-

ducted to explore the possibilities of using smartwa-

tches for health monitoring in home-based dementia

care. It was found that although the collected data

could not be seen as accurate and valid, it could pro-

vide valuable information and an indication for care-

takers.

Ehrler and Lovis (2013) performed a literature

study focusing on the drivers and barriers of smartwa-

tch use for seniors. Their findings suggest that smart-

watch’ sensors could be useful in case of emergency

situations. For example, accelerometers can be used

to detect a situation where a person falls. GPS can

be used to track and/or assist a user when they are

lost. Additionally, the emergency response systems

available on the smartwatch, such as alarm buttons,

can increase the autonomy of seniors (Mann et al.,

2005). While traditional emergency response systems

limit the freedom of movement of the senior by requi-

ring them to stay in the vicinity of a homebound recei-

ver unit, the smartwatch affords a much larger range

of movement. Furthermore, compared to smartpho-

nes or tablets that are not always carried around, the

smartwatch is a ubiquitous device that the user can ea-

sily wear around their wrist, thereby increasing chan-

ces of easy access in an emergency situation. Anot-

her advantage is that the smartwatch might not be

perceived as stigmatizing by seniors. Emergency re-

sponse systems are directly noticeable for bystanders

or friends, resulting in seniors finding them stigma-

tizing (Zwijsen et al., 2011). However, a smartwa-

tch is both less noticeable physically, and does not

portray an image of dependency. Quite the contrary,

it is associated with an image of tech-savviness and

independence. Additionally, a large number of ap-

plications including reminder systems, calendar, or

voice memos are available for the smartwatch. Since

the smartwatch can be personalized, seniors can de-

cide for themselves which applications they need and

would like to have installed.

2.3 Barriers to using a Smartwatch

The current generation of seniors did not grow up

with technologies such as tablets, smartphones and

smartwatches. Many of them do not find it impor-

tant to learn how to control the interfaces and gestu-

res on these systems. Several studies have shown that

in order for seniors to adopt these technologies, seni-

ors have to be convinced that the technology is use-

ful for them – that it has real added value (Mallenius

et al., 2007; Tang and Patel, 1994; Conci et al., 2009;

Venkatesh et al., 2003). Research (Ehrler and Lovis,

2013) suggests that seniors may have mixed feelings

regarding the usefulness of a smartwatch. When com-

pared to traditional health devices, the smartwatch is

not intrusive. However, the watch is also a personal

accessory. A senior may very well be emotionally at-

tached to the current watch that he or she is wearing.

This can result in him or her being less inclined to

wear a smartwatch. Furthermore, seniors might have

the feeling that they need to wear such a tool because

something is wrong with them (Bostr

¨

om et al., 2013).

Besides barriers of the smartwatch that are rela-

ted to personal factors, several usability factors might

also become a hindrance when smartwatches are used

by senior citizens. One of these obstacles is the user

interface. Standard interfaces for seniors are designed

with large menus and fonts; making it easier for se-

nior citizens with bad eyesight to use them (Marcus,

2003). However, a smartwatch has a much smaller

screen compared with for example a smartphone or ta-

blet, resulting in a barrier for these users (Plaza et al.,

2011). Additional practical barriers include the limi-

ted battery life and relatively high price of the smart-

watch. In order for seniors to be persuaded to spend

money on buying a smartwatch they should be con-

vinced that a smartwatch can significantly improve

the quality of their life (Mallenius et al., 2007).

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

28

In one of the key studies to date, Rosales et al.

(2017) investigated how seniors used a smartwatch

over a period of two months. Interview results in-

dicated that many different factors are involved in the

initial phase of learning how to operate the devices.

It depends on whether the senior has prior experience

with using the technical devices, e.g. a smartphone

or tablet, and their overall level of technical skills. In

addition, personal interest, attitude towards the device

and whether or not they have social support, plays a

role. Interestingly, no problems were encountered, re-

garding the small screen of the smartwatch (cf. Plaza

et al., 2011) and the short battery life (cf. Ehrler and

Lovis, 2013). Additionally, participants did not see

the potential of using the smartwatch in order to solve

possible problems that seniors can face, such as sen-

ding out an alarm in case of an emergency, monitoring

health or improving physical activity (cf. Ehrler and

Lovis, 2013; Mann et al., 2005). Overall it seemed

that whether or not senior citizens are interested in

technology plays a key role in the initial acceptance

of the smartwatch (Rosales et al., 2017).

2.4 Knowledge Gap

As we can see from the related work, only a few stu-

dies have been conducted with smartwatches used in

real life context and/or with senior citizens. To date,

it is still unclear exactly which obstacles or advan-

tages seniors encounter when using the smartwatch

from the seniors’ perspective. The study by Rosales

et al. (2017) offers a valuable point of departure for

the current work. We aim to extend this work in two

ways. First, where Rosales et al. (2017) have expli-

citly chosen for participants who had prior experience

and were active users of smartphones, we would also

like to include people with little experience in using

smartphones. Although smartphone use is on the rise,

also in the senior demographic, still less than 50% of

all older adults own or use a smartphone (Pew Re-

search Center, 2017). In our study, we are also inte-

rested in drivers and barriers that are relevant for seni-

ors without technical experience or for people who are

not a priori interested in the smartwatch. Secondly, -

in terms of method - where Rosales et al. (2017) ex-

clusively relied on interview data, we aim to extend

the insights drawn from their study by using the diary

method in a real-life context. We hope this method

allows us to capture rich information in-situ and in-

the-moment. An exclusive reliance on interview data

may limit the richness of insights as participants have

to retrospectively remember and report experiences

that occurred over a two months period, thus poten-

tially missing, forgetting, or incorrectly remembering

experiences during the interviews. In addition to our

contributions in terms of user demographic and met-

hod, we also observed several contradicting findings

between the study by Rosales et al. (2017) and other

studies (Ehrler and Lovis, 2013; Mann et al., 2005;

Plaza et al., 2011), as discussed in section 2.3. In

order to address such discrepancies we need to furt-

her explore potential drivers and barriers that can arise

when smartphones are used in context, by a represen-

tative sample of older adults.

3 IDENTIFYING DRIVERS AND

BARRIERS

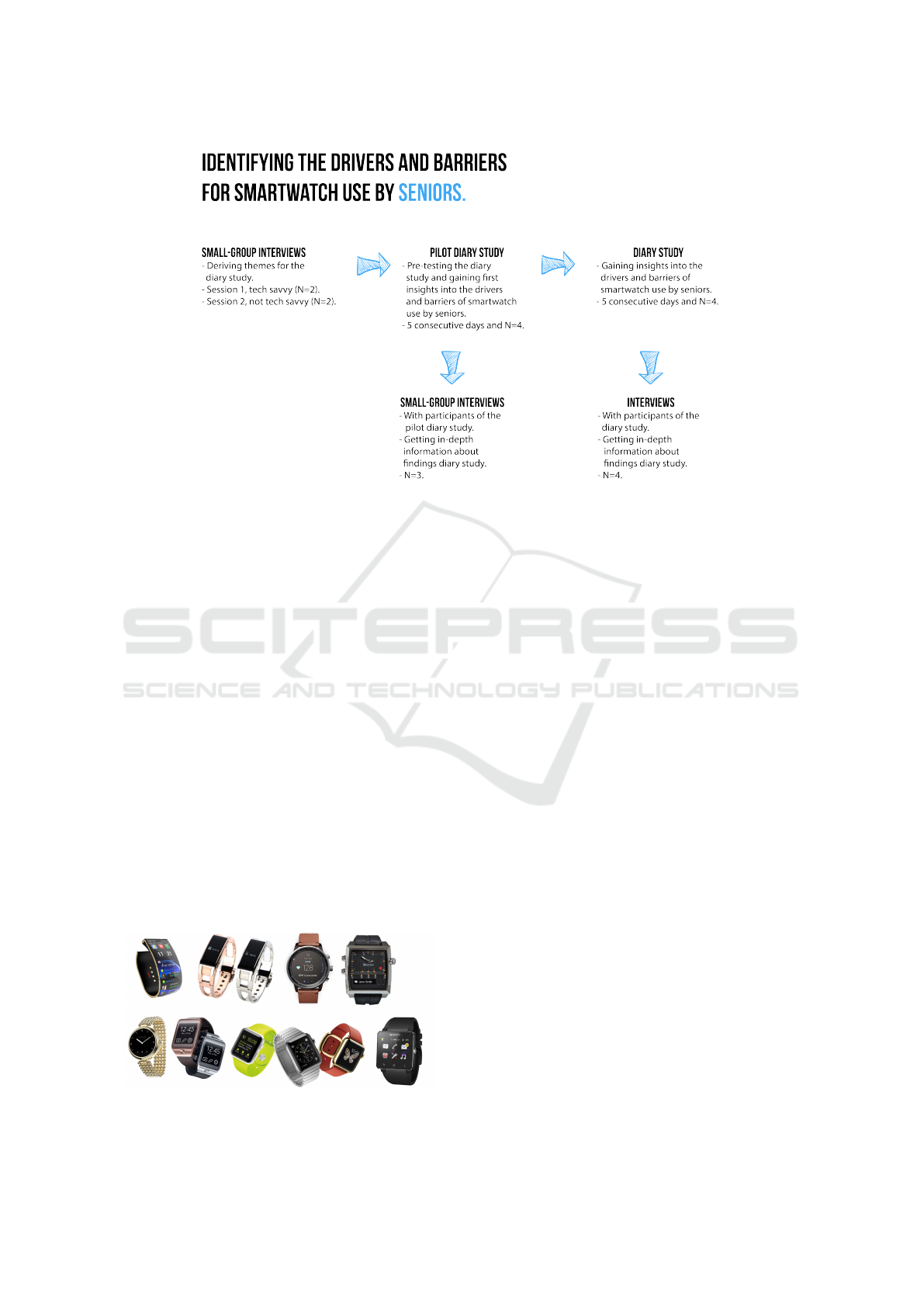

To further explore the possible drivers and barriers,

also for less technically-experienced seniors, and to

validate the findings of the study by Rosales et al.

(2017), several studies were conducted. In order to

get a clearer idea on which struggles or benefits might

arise when seniors use the smartwatch, it was cho-

sen to conduct a diary study, followed by an inter-

view with the participants. Figure 2 shows an over-

view of these studies. Initially, group interviews were

conducted, in order to define the themes for the di-

ary study. Once the themes were established, a pilot

study was conducted to pre-test the diary study fol-

lowed with a group interview in order to administer

final improvements of the final diary study described

in section 3.2.

3.1 Small-group Interviews

3.1.1 Participants

Participants of the interviews were recruited through

personal recruiting and by accessing the university de-

partment’s participant database. In total there were

four participants. These were divided into two groups,

participants who were tech savvy; P1,M, aged 70 and

P2,M with a age of 74 and participants who were not

tech savvy; P3,M aged 78 and P4,M aged 92. For this

study tech savvy was defined as participants who had

a technical background, either through work or hob-

bies. All participants were males indicated by the M

after the participant number.

3.1.2 Study Set-up

In total two interviews were conducted, one existing

of two tech-savvy people and one existing of two not-

tech savvy people. During the initial interviews two

researchers were present; one who acted as a modera-

tor and one who took notes. Prior to the start, parti-

Wear It or Fear It

29

Figure 2: Overview of the conducted studies.

cipants were introduced to the project, this was follo-

wed by the moderator asking participants to read and

sign the informed consent. Participants then received

an explanation of smartwatches, this included sho-

wing participants pictures and actual smartwatches,

as can be seen in Figure 3. Participants were then as-

ked questions, regarding themes such as: acceptance,

data privacy, functionality, UI, obstacles.

3.1.3 Materials

During the interviews, two smartwatches were shown;

the Moto 360 and the Samsung Gear. Participants had

the possibility to hold these and try them out. Par-

ticipants were also shown pictures from a selection

of smartwatches (Figure 3). For audio recordings a

smartphone was used.

3.1.4 Data Analysis

The data collected during the interviews were analy-

zed by means of a thematic analysis (Aronson, 1995).

Figure 3: Picture of different smartwatches, shown du-

ring the interviews.

Prior to the analysis, audio recordings of the inter-

views were transcribed verbatim. This was followed

by detecting and listing patterns from the data. These

different patterns were then grouped into correspon-

ding sub-themes. The next step was to validate the

chosen themes. This was done by going through the

related literature. Moreover, one week after the ini-

tial analysis, data was coded for a second time, in or-

der to validate that the understanding of the themes

was not a momentary reflection (Schreier, 2014). The

first author carried out this procedure and co-authors

performed a check of the suitability of the extracted

themes. Lastly, the themes are elaborated in the next

section, with the addition of quotes.

3.1.5 Themes for the Diary Study

Based on the interviews, it was derived which themes

were important to be further explored. These themes

were grouped into three categories: aesthetics, functi-

onality and attitude, and are elaborated next.

Aesthetics. One of the emerging themes during the

interviews was the looks and feel of the smartwa-

tch. Participants were pleased with the appearance

of the smartwatch, some praising its modern design

and ubiquity “I find this a very nice device, I like

the design and the readability is very good of this

device [Samsung smartwatch]....This [the smartwa-

tch] is easier than a phone, because I always have to

take it somewhere, I always have to put it in my poc-

kets..and this [the smartwatch] is always within my

reach (P2,M)”. It should be noted however that all

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

30

participants were male. It is therefore unknown yet

what views females would have on the overall appea-

rance of the smartwatch. Moreover, further explora-

tion is needed on readability, when the smartwatch is

used during daily live, meaning also in an outside en-

vironment and when used by participants with bad eye

sight. Additionally, concerns were raised with regard

to the usability and learning curve of the smartwatch.

It was predicted by participants, that for seniors who

do not have prior experience with touch screen devi-

ces it will be hard to learn how to operate a smartwa-

tch. Especially if interest is not there, this might be a

large barrier “I think that for seniors it is a barrier, if

you are not used to handle a phone... then it is three

steps too far (P2,M)”.

Functionality. The smartwatch offers a wide range

of functionalities that can be used. Participants per-

ceived this as a benefit. It was proposed that the

smartwatch could be suitable for health monitoring,

sending reminders; e.g. for the intake of medicines

or to send out an alarm in emergency situations “The

beauty of it, what would be easy, would be that for

people who need to take in medicines, it is easy to set

when they have to take in something (P1,M)”. Ho-

wever, participants also raised the concern that for

some seniors the many functionalities on the smart-

watch might be overwhelming “The target group is

not handy with it, and then there is just too much

on that thing [smartwatch], which they don’t need

(P1,M)”. Another concern was data privacy, when as-

ked about this during interviews, opinions varied on

who should have access to stored data. However,

more in-depth information is needed on this, also with

regard to the view of females.

Attitude towards the Smartwatch. There was a

clear distinction between the attitude towards the

smartwatch between the tech savvy participants, who

embraced the smartwatch “Yeah, I would like to buy

one (P2,M)” and the not tech savvy participants who

were of the opinion that they were too old for the

smartwatch and that it was more suitable for youn-

ger generations or more technical experienced seniors

“We are actually too old for that (P4,M)”. However,

further exploration is needed in the diary study in or-

der to explore whether a change in attitude can occur

after not tech savvy participants experience using the

smartwatch and see the potential of it in their lives.

3.2 Diary Study

Based on the themes discussed above we conducted

a diary study in the field. The diary study was pre-

tested during a pilot. Based on the pilot adjustments

were made to the design of the diary study.

3.2.1 Participants

Participants of the diary study were recruited through

personal recruiting. The diary study had four partici-

pants with an age ranging between 64-75, containing

three female participants and one male participant, in-

dicated by either a F or M after the participant num-

ber. Participants were a mixture of tech savvy and not

tech savvy seniors. This was asked about, prior to the

study, during the recruiting phase. The diary was in

Dutch, all participants were fluent in Dutch. P8,M is

65 years old. He has worked independently for 35

years, but was forced to quit after an accident on the

work field. His hobbies are fishing and crafts. Ad-

ditionally, he is interested in technology and tries to

help his friends and neighbors whenever they encoun-

ter problems with their computer. P7,F is the wife of

P8,M. She is 64 years old and used to work as fa-

mily caregiver. Her hobbies are cooking and crochet.

She has prior experience working with computers, but

does not see herself as a tech savvy person. Both she

and her husband do not obtain touch screen devices.

P5,F is a 75 year old widow. She has experience using

a computer and a smartphone, which were introduced

and explained by her granddaughter. Personally, she

is not interested in technology and she often gets ner-

vous using technological devices. However, at the ur-

ging of her daughter and granddaughter she tries to

keep up with technology. P6,F is 74 years and used

to work as city watchman and in hospitality. She is a

very active person, who has exercising as hobby. She

keeps up with technology and is an active user of her

laptop, tablet and smartphone.

3.2.2 Study Set-up

In order to pre-test the diary study, a pilot with 4

participants was conducted. This pilot took place

for 5 consecutive days, with participants receiving a

Samsung Galaxy Gear, Samsung Gear 2 or Moto 360

smartwatch. Based on the pilot, adjustments were

made to the diary book and the study itself. Additi-

onally, a group interview was conducted, containing

3 out of the 4 participants from the pilot. Objective

of this was to get more in-depth information on the

findings of the pilot. After the pilot and group inter-

view, the main diary study, containing 4 new partici-

pants and lasting of five consecutive days was con-

ducted. Prior to the start, participants were visited by

the researcher in their homes. During this visit, in-

structions were provided regarding the study and the

smartwatch, and a diary booklet was handed to the

Wear It or Fear It

31

participants. After five days, the researcher visited

the participants’ homes a second time. During this vi-

sit, participants were interviewed based on the insight

from the diary booklet as well as predefined questi-

ons. After the interview was concluded, participants

received a small monetary reward and were thanked

for their participation.

3.2.3 Materials

At the start of the study, participants received the

Samsung Gear S smartwatch and a stylus to interact

with the smartwatch. The smartwatch contained a set

of pre-installed applications, e.g. games, newspapers,

SOS applications, navigation, money converters and

health related applications. Furthermore, all partici-

pants were given a digital copy of the user manual of

the smartwatch.

Additionally, every participant received a diary

booklet. The diary booklet contained questions and

tasks for each consecutive day. Each day had its

own theme; Introduction to the smartwatch, Health,

Contact, Free day (decide for yourself whether and

how you want to use the smartwatch) and Evaluation.

During the 5 days, participants were free to use the

smartwatch as they pleased. In addition, they were

also asked, in the booklet, to try a specific applica-

tion each day; e.g. game, phone, text message, he-

art rate monitor and step counter. Figure 4 shows the

package each participant received. Figure 5 shows a

diary book entry.

3.2.4 Results

The data collected during the diary study was analy-

zed by means of a thematic analysis (Aronson, 1995).

The audio recordings of the interviews with the par-

ticipants of the diary study were transcribed verba-

tim. From all collected data patterns of opinions and

experiences were listed. The different patterns were

then grouped into corresponding sub-themes. The

next step was to validate the chosen themes. This was

done by going through the related literature. Moreo-

ver, one week after the initial analysis, data was co-

ded for a second time, in order to validate that the

understanding of the themes was not a momentary re-

flection (Schreier, 2014). The first author carried out

this procedure and co-authors performed a check of

the suitability of the extracted themes. Lastly, the the-

mes are elaborated in the next section, with the addi-

tion of quotes.

Privacy. Regarding the theme of data privacy, it was

found that opinions varied. While 2 participants indi-

cated not having problems sharing data acquired by

Figure 4: Package for the diary study.

Figure 5: Diary book entry.

the smartwatch, with their children, “Knows almost

everything (P5,F)” “Then directly informed (P6,F)”,

there was on the other hand also one participant: P7,F,

who did not want her children to get access to her

personal data. However, all participants were open to

sharing their data with their doctor. Participants indi-

cated that this allowed their doctor to monitor their

health. Additionally, it allowed them to alert their

doctor, in case of threatening circumstances “If so-

mething happens you can call them (P8,M)”. More-

over, participants expressed the need of being able to

control your own data, meaning, having the possibi-

lity, to decide for themselves, which data is shared,

especially with regard to sharing data with third par-

ties “With my own input (P7,F)”, “If I can decide it

myself (P8,M)”. There was also a problem with pri-

vacy, with regard to the calling application. On the

smartwatch a conversation is through a speaker, allo-

wing bystanders to overhear the conversation. For one

participant this was a reason to not use the application

very often “The sound, if I was in the store and they

called me, everyone could intercept the conversation.

(P6,F)”

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

32

Appearance. The greater part of the participants

were satisfied with the overall look and appearance

of the smartwatch “The design fits the time (P8,M)”,

“I found it bold, yeah I really liked it, also the mo-

del (P6,F)”. It seemed that this was facilitated by

the reactions of their environment, towards them we-

aring a smartwatch. “people in the train were look-

ing at us, they maybe thought what is that old wo-

men doing. (P6,F)”, “Yeah, people really noticed

it, in the stores, everywhere. (P7,F)”. This, resulted

in some of the participants experiencing a feeling of

pride, when wearing the smartwatch, as they recei-

ved positive attention and due to the uniqueness of

the device “It is something new, modern, not everyone

has it (P8,M)”. Moreover, participants indicated that

they preferred the smartwatch over traditional assis-

tive devices “A smartwatch [over traditional devices]

without a doubt. (P8,M)”, “Because the people, they

say if they wear that thing around their neck, yeah we

have it somewhere in the house, this [the smartwatch]

is easier” (P7,F).

However, there were also remarks on the design

of the smartwatch. One of the participants indica-

ted that for her the smartwatch was too heavy, as she

has thin wrists “it is too big and too heavy...because

I have thin arms and a small wrist (P6,F)”. Another

participant expressed that the smartwatch design was

more suitable for males, due to the large size. Mo-

reover, she indicated that watches with a rectangle

screen are more suitable for man, while watches with

a round screen are more suitable for women “I think

that round is more charming for a women. I found

it more of a man’s watch.. because of its big format.

(P5,F)”.

Small Screen. All participants encountered diffi-

culties with the small screen of the smartwatch. Espe-

cially typing was found challenging. These difficul-

ties occurred mostly when participants tried to send

a text message. Since the screen and therefore the

selection area on the smartwatch is rather small, it

was difficult for participants to select the right letter

“The most difficult was to type a message.” (P5,F),

“You have to practice a lot because the booths are too

small (P6,F)”. This also resulted in participants sen-

ding messages containing several typing errors “Be-

cause the image is so small, with your finger, you are

just next to it, ... I made strange words. (P5,F)”. One

of the participants also encountered difficulties when

using the smartwatch outdoors. The reason for this

was her having to put on her reading glasses, which

can be quite a hassle if you are walking with a group

and your glasses are located in your bag “That is dif-

ficult, you have to first get your glasses if you receive

a message, it depends where you are (P5,F)”. One of

the other participants, who did not experience diffi-

culties with reading or typing, did however experience

eye strain. This occurred whenever she played a game

for too long. This resulted in her vision becoming

blurry “If you have played games after a while, then

you had.. blurriness. (P7,F)”.

Useful Applications. Throughout the 5 days, the

application Calling was used most frequently by the

greater part of the participants. One participant in par-

ticular attached great value to the Calling application.

When asked about this during the interview, he ex-

plained that during an accident he lost his phone while

falling from a shelf. However, the chance of losing a

smartwatch during a fall, is less likely to occur, as the

smartwatch is securely attached to your wrist. The-

refore, if an emergency situation occurs, you can re-

ach for your smartwatch in order to call for help “If I

bump my head or fall, then I have it at hand...maybe I

have the opportunity then to say I need help. (P8,M)”.

Another participant was however more interested in

the health related applications, such as the heart rate

monitor and step counter, both of which she used fre-

quently, especially as she was still active in sports.

This functionality allowed her to keep track of her

progress.

Barriers when using Applications. During the 5

days of the diary study, participants also encountered

obstacles while using certain applications. One was

the language setting of applications. While the smart-

watch interface itself was in Dutch, several third-party

applications were in English. Not all participants

were able to comprehend the English language, the-

refore they were not able to use these particular appli-

cations “You are busy reading something in Dutch..

a new function appears, and you continue but it is

explained in English what you have to do. Since I

do not understand any English it is goodbye for me

and I am back at the beginning (P8,M)”, “If every-

thing was in Dutch.. Yeah, then I could read it bet-

ter. (P6,F)”. Furthermore, the auditory notifications

of the Watermeter application (an application that re-

minds the user to drink water) were found disturbing

after a while by all participants “Yeah and I kept on

drinking the whole day, until I found it disturbing at a

certain moment. (P8,M)”, “Because you want to get

rid of that sound as quick as possible. (P6,F)”. Some

of the participant also encountered difficulties when

wanting to turn these notifications off “I pressed and

clicked on anything and everything, I had about pres-

sed everything before it was turned off. (P6,F)”. As

indicated by one participant, because the application

Wear It or Fear It

33

was in English, he was not able to turn it off “But they

explain everything perfectly fine in English, hence I

am not able to succeed (P8,M)”. With regard to the

health application, one participant noted that for her

these applications were disappointing, as it seemed

that the heart rate application was stuck on one value

and she doubted the validity of the step counter “Yeah

I found it disappointing, because it cannot exist that it

stays stuck on the same value [heart rate monitor], re-

gardless whether you walk faster or slower. (P6,F)”.

Overall Acceptance of the Smartwatch. Opinions

regarding interest in the smartwatch varied among

participants. Some participants were very enthusias-

tic about the smartwatch and acclaimed the ubiquity

of the smartwatch, especially when compared to a

smartphone. “Only benefits, I find this one easier than

the phone, you wear it around the wrist. You do not

have to continuously take a phone with you. (P7,F)”.

In contrast, an other participant was satisfied with her

mobile phone, which was small enough to take with

her everywhere “If I did not have a mobile phone

I would possibly get used to it [smartwatch], but I

have a mobile where I am used to, it is smaller, I can

put it between everything, so that is easier. (P5,F)”

. Another participant explained, that while currently

she was not interested in buying a smartwatch, she

might be in the future, if all the bugs were to be sol-

ved “I would only buy it if those changes were made..

if all the child diseases are solved. (P6,F)”. An in-

teresting observation was that P7,F, who was initially

not keen on participating in the study, as she found

herself not experienced enough, was very enthusias-

tic about the smartwatch. In contrast, another parti-

cipant, P5,F, who was also very skeptical beforehand,

remained so after the study. One important difference

between these two participants was that P7,F recei-

ved support of her partner, who had a technical back-

ground, while P5,F had to learn by herself. The price

of the smartwatch was also an issue for several par-

ticipants “If it would cost AC100.. you are then more

inclined to buy it (P8,M)”, “expensive (P5,F)”. Mo-

reover, it seems that interest and openness to use the

smartwatch also play an important role in seeing the

full potential of the smartwatch. Without it, seniors

may not be sufficiently motivated to explore the pos-

sibilities and functionalities of the smartwatch “You

need to be interested to do that, I do not have inte-

rest for it (P5,F)”, “By practicing a lot, really playing

with it and dare, really dare to tap, it gives a good fee-

ling if you make progress. (P6,F)”.

4 DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to get more in-depth insig-

hts on the potential drivers and barriers in smartwatch

acceptance by senior citizens, both for seniors that are

technically experienced and seniors that have no ex-

isting knowledge on touchscreen devices. Interviews

and a diary study, including 5 days of smartwatch use

in daily life, allowed us to get in-depth insights from

a small but varied number of seniors on the potenti-

als of these new devices. Overall the results of this

study are in line with the findings of Ehrler and Lo-

vis (2013), especially when looking at themes such as

usability, the smartwatch being a disruptive techno-

logy, price, ubiquity and safety. With regard to the

findings of Rosales et al. (2017), where participants

reported not to see great added value in smartwatches

in case of emergency or in health monitoring, our re-

sults deviate. In both the group interviews and the

diary study users mentioned the benefits of having a

smartwatch under circumstances of personal distress

or health risk, especially referring to the ubiquity of

the smartwatch, implying fast and easy access. It was

however mentioned during the group interviews, that

technically unexperienced users could face barriers in

benefiting from the watches in these situations. It is

unclear why the findings of our study and those of Ro-

sales et al. (2017) deviate from each other. A possible

explanation could be the type of smartwatch that was

used by Rosales et al. (2017), the Moto 360. This

smartwatch was pre-tested during our pilot, and the

fact that it could not operate as a stand-alone device

(i.e., without needing connection to a nearby smartp-

hone), was perceived as a large barrier by participants

in that pilot. In contrast, the Samsung Gear does make

it possible for users to text or call someone, without

needing a smartphone, thus effectively serving as a re-

placement of the smartphone and therefore making it

more suitable for emergency situations. In relation to

the ergonomics of the device, our results correspond

to the findings of Ehrler and Lovis (2013), who also

found that the small screen of a smartwatch may result

in difficulties for older adults, especially when typing

messages. One of the unique features of our work, in

comparison to other studies to date, is the inclusion

of non-tech-savvy seniors as part of our sample, the-

reby expanding current knowledge. When looking at

the results of the conducted studies it seems that prior

experience does not have to be a barrier per se, as it

can be overcome when the senior is aided by someone

who does have technical experience, e.g. partner or

children. Furthermore, having an open mind to the

potential added value of a smartwatch and feeling a

high level of self-efficacy in operating it, plays an im-

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

34

portant role in the acceptance of this technology, in

line with the model of McCreadie and Tinker (2005)

and the findings of Rosales et al. (2017). An impor-

tant aspect seems to be curiosity and a motivation to

explore new technology. Another important theme in

this study was data privacy. Overall the key lies in

giving participants control over their data, which en-

hances autonomy and makes it possible for them to

decide for themselves who they will give access to

their data, a preference that was clearly expressed by

participants. This is fully in line with the frequently

expressed need for autonomy (Portet et al., 2013).

Additionally, other expressed needs, such as secu-

rity and the ability to monitor one’s health also corre-

spond to the findings of this study. Especially, when

looking at preferred applications by seniors. Overall,

it seems that there are still barriers to overcome for

the smartwatch in order to be accepted by senior ci-

tizens. However many of the proposed barriers can

be addressed by improving usability of the smartwa-

tch. Most importantly, though, in order to enhance

acceptance of the smartwatch for senior citizens, the

device should have a clear added value for them. In

this sense, smartwatches are evaluated no differently

by older adults than other innovative communication

and information technologies that were introduced in

the past (Melenhorst et al., 2006; IIsselsteijn et al.,

2007). Here too, a benefit-driven approach seems to

dominate the motivated acceptance and use of new

communication technologies. Our results provide ten-

tative support that smartwatches carry specific added

value for older adults. When usability and cost bar-

riers are overcome, the smartwatch may be a good,

non-stigmatizing alternative or complement to traditi-

onal assistive devices.

5 LIMITATIONS

Recruiting seniors for this study was a challenge.

Most seniors, especially women, were not interested

in using a smartwatch, and did not see the added va-

lue of it. Furthermore, many seniors indicated to have

a busy life, therefore not having time to participate in

the study. However, in order to gain more in-depth in-

sights, a study with more participants and especially

a more diverse population is recommended. Additio-

nally, the running time of the diary study can be seen

as a limiting factor. Ideally, the study would have run

for a longer period of time - multiple weeks or even

months. This would allow us to gain more insights

in the appropriation of the smartwatch in the senior’s

daily life, becoming part of daily routines, rather than

focusing on specific, limited scenarios of use, impo-

sed by the researchers. However, as was observed du-

ring the diary study, for some of the participants 5

days of using and wearing the smartwatch was alre-

ady challenging.

6 FUTURE WORK

This study has focused on the drivers and barriers in

smartwatch acceptance of seniors. One of the barriers

in acceptance is the usability of the smartwatch. The

next step will therefore be to explore how usability of

the smartwatch can be improved for seniors. Additi-

onally, as previously discussed, a field study of lon-

ger duration, and a more diverse sample, would allow

us to gain a deeper understanding of the appropria-

tion of the smartwatch, and to explore which drivers

and barriers exist over a longer time period of time.

Moreover, exploring how social support (e.g. family

or friends) can positively influence acceptance of the

smartwatch would also be of interest, as social uses

of information and communication technologies are a

major factor in their acceptance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all seniors that participated in the studies.

Additionally, we thank Daphne Miedema, Bo Liu and

Haoying Cheng, for helping with the set-up and exe-

cution of the small-group interviews and pilot diary

study.

REFERENCES

Abrahao, A. L., Cavalcanti, A., Pereira, L., and Roque, L.

(2014). Accessibility study of touch and gesture inte-

raction with seniors. SBC Journal on Interactive Sys-

tems, 5:27–38.

Aronson, J. (1995). A pragmatic view of thematic analysis.

The qualitative report, 2:1–3.

Becker, S. A. (2004). A study of web usability for older

adults seeking online health resources. ACM Tran-

sactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI),

11:387–406.

Boletsis, C., McCallum, S., and Landmark, B. F. (2015).

The use of smartwatches for health monitoring in

home-based dementia care. In International Confe-

rence on Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Popula-

tion, pages 15–26. Springer.

Bostr

¨

om, M., Kjellstr

¨

om, S., and Bj

¨

orklund, A. (2013). Ol-

der persons have ambivalent feelings about the use of

monitoring technologies. Information Technology and

Disabilities, 25:117–125.

Wear It or Fear It

35

Cecchinato, M. E., Cox, A. L., and Bird, J. (2015). Smart-

watches: the good, the bad and the ugly? In Procee-

dings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended

Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

pages 2133–2138. ACM.

Chappell, N. L. and Zimmer, Z. (1999). Receptivity to new

technology among older adults. Disability and Reha-

bilitation, 21:222–230.

Conci, M., Pianesi, F., and Zancanaro, M. (2009). Useful,

social and enjoyable: Mobile phone adoption by older

people. In Human-Computer Interaction–INTERACT

2009, pages 63–76. Springer.

Czaja, S. J. and Lee, C. C. (2007). The impact of aging on

access to technology. Universal Access in the Infor-

mation Society, 5:341–349.

Demiris, G., Rantz, M. J., Aud, M. A., Marek, K. D., Tyrer,

H. W., Skubic, M., and Hussam, A. A. (2004). Ol-

der adults’ attitudes towards and perceptions of’smart

home’technologies: a pilot study. Informatics for He-

alth and Social Care, 29:87–94.

Ehrler, F. and Lovis, C. (2013). Supporting elderly ho-

mecare with smartwatches: advantages and draw-

backs. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics,

205:667–671.

Fuchsberger, V. (2008). Ambient assisted living: elderly

people’s needs and how to face them. In Proceedings

of the 1st ACM International Workshop on Semantic

Ambient Media Experiences, pages 21–24. ACM.

GGZ Drenthe (2013). Lichamelijke klacht en ouderen.

Website. last checked: 21.7.2017.

Gould, J. D., Boies, S. J., and Lewis, C. (1991). Making

usable, useful, productivity-enhancing computer ap-

plications. Communications of the ACM, 34:74–85.

Gudur, R. R., Blackler, A. L., Popovic, V., and Mahar, D. P.

(2009). Redundancy in interface design and its impact

on intuitive use of a product in older users. IASDR

2009 Rigor and Relevance in Design, pages 209–209.

IIsselsteijn, W., Nap, H. H., de Kort, Y., and Poels, K.

(2007). Digital game design for elderly users. In Pro-

ceedings of the 2007 Conference on Future Play, pa-

ges 17–22. ACM.

Legris, P., Ingham, J., and Collerette, P. (2003). Why do

people use information technology? a critical review

of the technology acceptance model. Information &

Management, 40:191–204.

Mallenius, S., Rossi, M., and Tuunainen, V. K. (2007). Fac-

tors affecting the adoption and use of mobile devi-

ces and services by elderly people–results from a pilot

study. 6th Annual Global Mobility Roundtable, 31.

Mann, W. C., Belchior, P., Tomita, M. R., and Kemp, B. J.

(2005). Use of personal emergency response sys-

tems by older individuals with disabilities. Assistive

Technology, 17:82–88.

Marcus, A. (2003). Universal, ubiquitous, user-interface de-

sign for the disabled and elderly. Interactions, 10:23–

27.

McCreadie, C. and Tinker, A. (2005). The acceptability

of assistive technology to older people. Ageing and

Society, 25:91–110.

Melenhorst, A.-S., Rogers, W. A., and Bouwhuis, D. G.

(2006). Older adults’ motivated choice for technologi-

cal innovation: evidence for benefit-driven selectivity.

Psychology and Aging, 21:190.

Nap, H. H., De Greef, H. P., and Bouwhuis, D. G. (2013).

Self-efficacy support in senior computer interaction.

International Journal of Cognitive Performance Sup-

port, 1:27–39.

Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid (2017). Vergrijzing:

Wat is de huidige situatie? Website.

Nickerson, R. S. (1981). Why interactive computer systems

are sometimes not used by people who might bene-

fit from them. International Journal of Man-Machine

Studies, 15:469–483.

Ouderenfonds (2017). Feiten en cijfers - het nationaal ou-

derenfonds. Website. last checked: 26.1.2016.

Pew Research Center (2017). Tech adoption climbs among

older adults en ouderen. Website. last checked:

13.10.2017.

Plaza, I., Mart

´

ın, L., Martin, S., and Medrano, C. (2011).

Mobile applications in an aging society: Status and

trends. Journal of Systems and Software, 84:1977–

1988.

Portet, F., Vacher, M., Golanski, C., Roux, C., and Meillon,

B. (2013). Design and evaluation of a smart home

voice interface for the elderly: acceptability and ob-

jection aspects. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing,

17:127–144.

Rijksoverheid (2016). Seniorenwoningen. Website. last

checked: 26.1.2016.

Rosales, A., Fern

´

andez-Ard

`

evol, M., Comunello, F., Mu-

largia, S., and Ferran-Ferrer, N. (2017). Older people

and smartwatches, initial experiences. El Profesional

de la Informaci

´

on (EPI), 26:457–463.

Schreier, M. (2014). Qualitative content analysis. The

SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis, pages

170–183.

Tang, P. C. and Patel, V. L. (1994). Major issues in user

interface design for health professional workstations:

summary and recommendations. International Jour-

nal of Bio-Medical Computing, 34:139–148.

van Duin, C. (2007). In 2013 bijna 400 duizend 65-plussers

erbij. Website. last checked: 26.1.2016.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D.

(2003). User acceptance of information technology:

Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, pages 425–

478.

Yang, T. (2008). Appropriate user interface for the elderly.

Zwijsen, S. A., Niemeijer, A. R., and Hertogh, C. M.

(2011). Ethics of using assistive technology in the care

for community-dwelling elderly people: An overview

of the literature. Aging & Mental Health, 15:419–427.

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

36