Politeness Principles Expressed by Minangkabau Migrants in

Traditional Market: A Cultural Pragmatic Study

Ely Hayati Nasution

1

, Roswita Silalahi

1

, and Deliana

1

1

Department of English, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Jl. Universitas No. 19, Medan, Indonesia

Keywords: Cultural pragmatic study, Minangkabau migrants, Politeness principles, Technology, Violations,

Abstract: Politeness is a social as well as a universal phenomenon involving language as its representation to be

measured. Massive globalization and developing technology have contributed to the migration of people and

the language used by the speakers as well as the politeness applied. This paper aims at analyzing the politeness

principles represented by Minangkabau migrants in Halat traditional market in the city of Medan. This

research was the combination of library and field research by applying descriptive qualitative method focused

on a cultural pragmatic study supported with documentation, in-depth interview and questionnaire. It involved

12 (twelve) migrant sellers and buyers as the population and 3 (three) of them were selected as the sample.

The transcribed text obtained from the conversation happened between migrant sellers and buyers was

selected as the main data and the result of an in-depth interview and questionnaire was treated as additional

data. The research found 6 (six) politeness maxims proposed by Leech (2014) were found in the conversation

involving MK migrants in the selling and buying process, yet the violation of maxims also occurs. It shows

that globalization and technology contribute much to the language politeness of migrants Minangkabau in

their daily life.

1 INTRODUCTION

Politeness in general covers many aspects of human

life. One of the crucial aspects required by people as

the building blocks of a society is communication.

Communication itself encompasses the role of

language and politeness in order to manage the people

with various background and needs. In other words,

politeness and language must be present during

communication. It is difficult to define which comes

first or becomes the priority. Both are social as well

as a universal phenomenon found around the world.

Politeness itself has become a prominent issue to be

discussed as it has been viewed from different

perspectives (Shahrokhi and Bidabadi, 2013): face-

saving view (Brown and Levinson, 1978,1987),

emotive communication and interpersonal politeness

(Arndt and Janney, 1985, 1991), discernment and

volition (Ide, 1989), social norm view and

conversational contract view (Fraser, 1990),

conversational maxim view (Grice, 1975; Leech,

1983, 2014; Lakof, 1989, 1990), rapport management

(Spencer-Oatey, 2000), intercultural communication

(Scollon and Scollon, 2001), even politic behaviour

(Watts, 2003, 2005). It also has been analyzed in

many areas: classroom (Jiang, 2010), advertisement

(Liu, 2012), administration (Hammond, 2017), a

movie (Budiarta and Rajistha, 2018), etc. Moreover,

politeness has received various amounts of attention

from all areas of linguistics throughout the twentieth

century (Held, 1992). It represents that significantly

politeness is still attractive to be studied further and

wider. However, analyzing politeness principles in

which traditional market used as the research of

location and the speakers are migrants speaking in

their native language is still limited conducted. Thus,

this research tries to analyse this problem thoroughly.

Language as a primary media in communication

presents among the communities in order to bridge

any existing purposes. It is definitely accepted that

language has a closed relationship with politeness. In

linguistics, politeness is a well-established scholarly

concept, basic to ‘politeness theory’ – one of the more

popular branches of contemporary pragmatics, and a

widely used tool in studies of intercultural

communication. It has been improved for many years

with certain emphasize of its functions through

politeness principles. One of the notable theories on

1864

Nasution, E., Silalahi, R. and Deliana, .

Politeness Principles Expressed by Minangkabau Migrants in Traditional Market: A Cultural Pragmatic Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0010104618641870

In Proceedings of the International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches (ICOSTEERR 2018) - Research in Industry 4.0, pages

1864-1870

ISBN: 978-989-758-449-7

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

politeness proposed by Leech (2014) emphasizing the

notion of politeness on an atmosphere of relative

harmony in social interaction described on eight

characteristics, they are: 1) it is not obligatory, 2)

varying gradations of polite and impolite behavior, 3)

a sense of what is normal, 4) depends on situation, 5)

reciprocal asymmetry, 6) battle of politeness, 7)

transaction of value and 8) a balance among

participants. These characteristics are used generally

in order to classify what being polite or impolite.

Furthermore, Leech improved the correlation

between politeness and language in the form of

maxims of the politeness which are divided into 6

(six) types, they are:

1. Tact maxim: minimize the cost to other, maximize

the benefit to other.

2. Generosity maxim: minimize benefit to self,

maximize cost to self.

3. Approbation maxim: minimize dispraise of other,

maximize praise of other.

4. Modesty maxim: minimize praise of self,

maximize dispraise of self.

5. Agreement maxim: minimize disagreement

between self and other, maximize agreement

between self and other.

6. Sympathy maxim: minimize antipathy between

self and other, maximize sympathy between self

and other.

These principles indicate that politeness basically

tends to build good relation among the community

members or simply speakers involved in a

communication process. In Indonesia, everyone

appreciates politeness as one of the Indonesian

personality characteristics instead of cultural

diversity. It is still considered as a crucial aspect

embedded within the culture of a community. A

number of different factors involved in determining

politeness, such as behavior, status, language, culture,

etc. also contribute to the politeness. However, being

polite or impolite is actually relative and naive as

there is disagreement on the parameters or criteria

related to it. It indicates there is a gap occurring due

to the differences existing among generations. The

simple illustration given here is the age difference

between young and old. This difference influences

the way of thinking of each generation and sometimes

leads problems; for instance, the youngsters must

speak in a lower tone to the elders, listen to their

advice or ask for their suggestion of doing or planning

something; therefore, they must consider the way to

express the language and the language used, yet they

often ignore these things. For youngsters, politeness

is an obstacle for their life since it makes them

become unconfident and outdated, especially dealing

with local language. The rules purposed for politeness

make them feel discomfort or in other words;

youngsters need the feeling of freedom, included in

the communication. It is also supported by the

development of technology which partially also

causes the youngsters to leave the politeness

principles in communication. As a result, it leads

them to the image of ‘polite’ or ‘impolite’.

Furthermore, in Indonesia, everyone appreciates

politeness as one of the Indonesian personality

characteristics instead of its cultural diversity. Multi-

ethnic enriching and supporting national identity

become one of the Indonesian culture diversities.

Each ethnic has certain characteristics reflecting any

cultural features belonged to it; believed, performed,

and integrated into the community. The language

itself can be regarded as the first acquired and

developed by an ethnic which has significant

functions and roles for the people living with it. This

language is commonly known as vernacular language

or local language designating the ethnic itself. For

instance, Minangkabau people with Minangkabau

language, Batak people with Batak language,

Javanese with Java language, etc. Minangkabau

language is one of the local languages spoken

throughout the Indonesian archipelago due to the

Minangkabau marantau tradition of migration with

approximately seven million speakers (Drakard,

1999). It is an Austronesian language primarily

spoken by Minangkabau ethnics living in the

highland of West Sumatera (Gordon, 2005), which is

known as Minang or Padang language and becomes

a daily language used for communication for a long

time and identic with rhythmical intonation. This

language has both a pragmatically motivated voice

system and a conceptually motivated voice system

(Crouch, 2009). This rhythmical intonation even can

denote meaning for the politeness of the speaker. For

example, the high and loud tone of a speaker is

considered as impolite if she/he talks to others,

especially for the older. Moreover, according to

Azrial (2008) in Kurniawan and Isnanda (2014),

Minangkabau people has certain rule related to

language they use in their daily communication which

is known as Nan Ampek (The Four), consisting of

Kato Mandaki (the language used to the elders), Kato

Manurun (the language used to the younger), Kato

Mandata (the language used to the same age), and

Kato Malereng (the language used to the honors).

Thus, MK people try to maintain their local language

in every activity as for them language is also the

representation of politeness.

Politeness Principles Expressed by Minangkabau Migrants in Traditional Market: A Cultural Pragmatic Study

1865

Developing and massive globalization has led

MK people to take part in mobilization for various

reasons and purposes. Demographically, in

Indonesia, it will be found in many ethnic

communities that have out-migrated to places outside

their homelands. They become migrants (perantau)

and spread throughout the Indonesian archipelago. It

certainly affects the socio-cultural and language

domains of the migrants as they have to adapt to the

new places and it leads them to disengage from their

own culture. They come from various ethnics in

Indonesia, such as Bataknese, Javanese, Malay, and

Minangkabau. North Sumatera Province is one of the

preferred regions by the migrants to live in. Medan as

the capital city becomes the most favorite destination

to settle permanently for it offers economic

potentiality for migrants to support their life. Medan

is interesting to be selected as the location of the

research as it consists of various ethnics or plural

communities either as natives or migrants who are

different from other cities or regions in Indonesia. It

is difficult to find a person speaking in local dialects

for daily language differ from other cities in

Indonesia, for instance in Java. People living in part

of Java will be easier to be recognized due to their

special dialect, yet it will be different from the

migrants living in Medan, especially for MK people.

Consequently, other ethnics must go to certain places

in order to find out MK people speaking in their

native language, for instance, a traditional market.

Minangkabau ethnic is one of the most migrants

living in Medan. They live in certain districts in part

of Medan, such as Matsun, Halat, Perjuangan,

Sukaramai, etc. Most of them working as merchants

or sellers at the traditional market around their homes.

It has become their job since their ancestors are also

well-known as traders. Thus, nearby markets are

labeled by MK markets as the sellers and buyers are

dominated by MK people, one of them is Halat

market located at City of Medan.

MK migrants are used to practicing MK language

to interact with each other and politeness becomes an

obligation in selling and buying transaction. It is

actually a hard fact to be challenged as in the reality,

the situation and condition encountered have made

and led them to speak language other languages to

build communication in selling their goods or

products. It means that politeness principles dealing

with language must be maintained to achieve good

interpersonal relationship during selling and buying

transaction, yet the violation toward it may take place.

Thus, this research aims at analyzing six types of

maxims of principle politeness expressed by MK

migrants in Halat traditional market and the

violations occur towards those maxims during selling

and buying transaction in order to provide a new

model of identifying the level of language politeness

used by speakers.

2 METHOD

This research was the combination of library and field

research by applying descriptive qualitative method

supported with documentation, in-depth interview

and questionnaire. 12 (twelve) Minangkabau

migrants working as sellers were selected as

population and 3 (three) of them together with the

buyers became the sample of the research. The

transcribed text obtained from the recorded

conversation happened between migrant sellers and

buyers was selected as the main data and the result of

an in-depth interview and questionnaire was treated

as additional data.

The main data then were translated into

Indonesian language and English in order to find out

six types of maxims of the politeness proposed by

Leech (2014) used by Minangkabau migrants at Halat

traditional market. However, only the conversations

translated into English were displayed in the analysis.

The translated conversations in the Indonesian

language were only used in order to help the translator

in understanding the message of information

conveyed by the speakers and translating them into

English. These data then were compared with the

violations occurred and were analyzed by using the

data from the result of an in-depth interview and

questionnaire.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The data of this research were conversations of MK

migrants working as sellers and their buyers at Halat

international market. The conversation was recorded

and transcribed. After that, the conversation was

translated into Indonesian Language and English and

was used as the analyzed data. Based on the result of

analysis, it was found that all six types of maxims of

politeness principles; tact maxim, generosity maxim,

approbation maxim, modesty maxim, agreement

maxim, and sympathy maxim improved by Leech

(2014) were used in the conversations expressed by

the MK migrants working as sellers with their buyers

at Halat Traditional Market, however, the violations

also occur, as shown in the actions illustrated in table

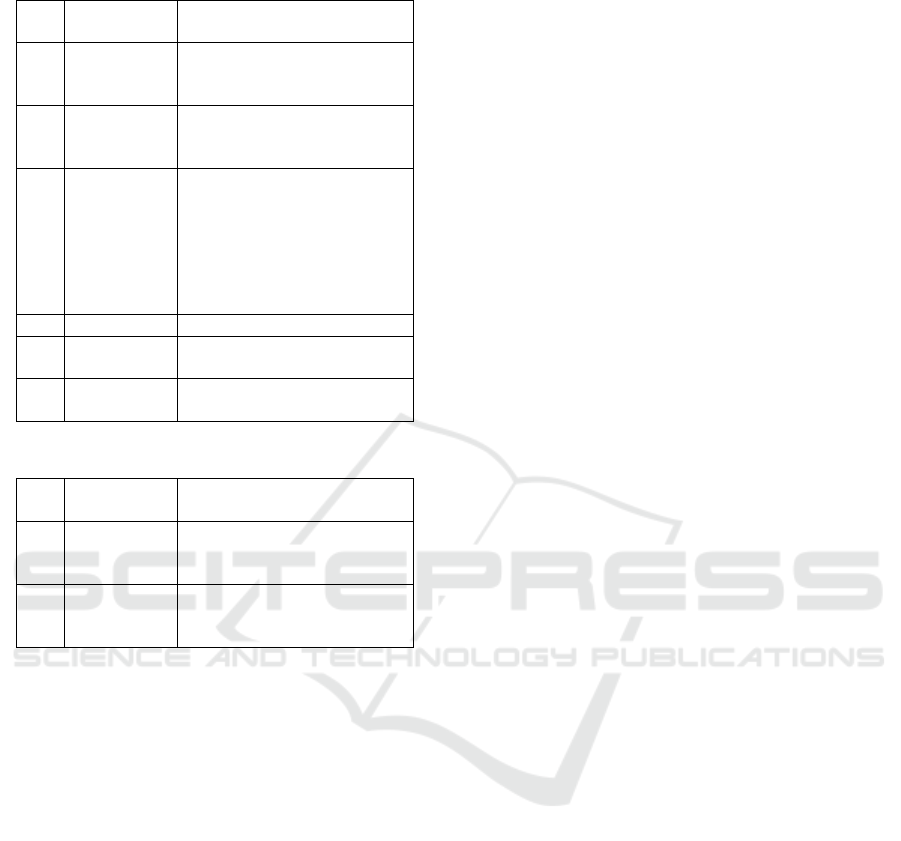

1 (one) and table 2 (two).

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1866

Table 1: Actions Represented Politeness Maxim

No.

Politeness

Maxims

Actions

1

Tact

- Patiently gives reasonable

opinions to ensure the buyer

for her choice.

2

Modesty

- Greets the buyer friendly

and politely to see her

goods.

3

Approbation

- Praising the buyer by

saying ‘thank you’.

- Answering the buyer’s

questions.

- Doing what the buyer

asks/orders without

complaining.

4

Generosity

- Giving a cheaper price.

5

Agreement

- Agreeing to give the price

determined by the seller.

6

Sympathy

- Asking for forgiveness for

the inconvenience.

Table 2: Actions Represented Violations of Maxim

No.

Violations

of Maxims

Actions

1

Generosity

- Feeling reluctant to give

the lower price to the buyer

by describing strict reasons.

2

Agreement

- Deciding the final price and

neglecting the buyer’s

request.

The occurrence of the maxim of politeness table 1

(one) represents that MK Migrants working as sellers

in the traditional market still maintain the politeness

of language in interaction. It is certainly supported by

the primary aim of sellers in selling and buying

process, to attract buyers in order to buy their

products through the process of bargaining and the

agreement of price, as illustrated in conversation 1

(one):

Conversation 1

Buyer :

Iko bara ciek, Pak?

(How much is it, Sir?)

Seller :

Mano, Mak? Iko? Dua limo.

(Which one, Madam? This one? It is

twenty thousand rupiah.)

Buyer :

Lai warna lain?

(Are there other colors?)

Seller :

Ado. Merah.

(Yes, it is red.)

Buyer :

Mano? Caliak.

(Which one? Can I see?)

Seller :

Iko.

(Here it is.)

Buyer :

Indak kurang ko haraganyo?

(Can it be cheaper?)

Seller :

Dua tigo.

(Twenty-three thousand rupiah.)

Buyer :

Dua puluah yo?

(How about twenty thousand rupiahs?

Seller :

Ambiaklah.

(Okay)

Buyer :

Tarimo kasi yo.

(Thank you.)

Seller :

Samo-samo.

(You are welcome.)

Conversation 1 (one) involves 2 (two) speakers,

one is a buyer (female) and another is a seller (male).

According to the data obtained through in-depth

interview and questionnaire, both are migrants, but

they come from different areas or hometowns of West

Sumatera Province. The former comes from Solok

and she has lived in Medan for more than 50 (fifty)

years. She moved to Medan for getting an

economically better life for her family. The latter

comes from Payahkumbuh and he also has lived in

Medan for more than 50 (fifty) years. He migrated to

Medan to get a better job, but finally, he decided to

be a seller and make a life hereafter.

Based on the result of the analysis of conversation

1 (one), it is found that there are 3 (three) maxims

exemplified; approbation maxim, generosity maxim,

and agreement maxim. The approbation maxim is

described in the conversation started by a buyer

asking for the price of a pair of sandals. The seller

appreciates the buyer by answering the buyer’s

question. After that, the buyer gives another question;

asking about alternative colors and the seller again

patiently answers that question. Then, it is continued

with the buyer's request to show the sandals which she

asks for and the seller gives the sandals immediately.

These parts of conversation imply that the seller tries

to minimize dispraise of other and maximize praise of

other. The conversation is continued by the buyer by

asking for cheaper price and the seller generously

gives the lower price, yet unpredictably the buyer

bargains the sandals for the lowest price and the

seller, agrees with her. This situation reflects that the

seller also tries to minimize benefit to self, maximize

cost to self or in politeness principles it is categorized

as generosity maxim. The conversation is ended by

the agreement on price between seller and buyer as a

form of the maxim of agreement and thanking

expression from the buyer for kindly giving what she

wants and needs, especially dealing with the price and

the buyer responds it well.

The whole utterances in the conversation indicate

that both, buyer and seller maintain politeness during

Politeness Principles Expressed by Minangkabau Migrants in Traditional Market: A Cultural Pragmatic Study

1867

the selling and buying process. Since both are about

the same age, so they speak the language to the same

age (kato mandata) which makes them feel more free

in expressing what they want. In other words, the

language they use will support them in selling and

buying transaction even though they have migrated

for years. However, this situation does not happen if

the seller and buyer have the different level or type of

the language used, as described in conversation 2

(two):

Conversation 2

Seller :

Apo caliak? Singgahlah siko sabantah.

(Come and see, Madam.)

(A buyer points a long dress.)

Buyer :

Baranya ko, Uni?

(How much is it?)

Seller :

Saratuih ribu.

(One hundred thousand rupiah.)

Buyer :

Indak kurang?

(Can it be cheaper?)

Seller :

Ado kurang. Bisa.

Awak sama awak yo.

(Yes, it can. You are Minang, aren’t

you?)

Buyer :

Hijau barendo.

(But, I do not like the green dress with

lace.)

Seller :

Ndak barendo. Kombinasi. Rancak.

(It is not full of lace, it is a combination.)

Buyer :

Baranya ko, Uni?

(How about this one. How much is it)

Seller :

Iko hargo saratuih dua puluah.

(It is one hundred and twenty thousand

rupiah.

Buyer :

Indak kurang?

(Can it be cheaper?)

Seller :

Beko bertransaksi tak tawar menawar.

Iko alah harago pas. Ndak bisa ditawar

lai.

(You do not need to bargain as I always

give the lowest price. It cannot be

bargained. It is a fixed price.

Buyer :

Baranyo kuniang?

(How much is the yellow dress?)

Seller :

Saratuih ampek puluah.)

(One hundred and forty thousand.)

Buyer :

Iko punya jadi bakuranglah haraganyo.

Saratuih dua puluah yo?

(Would you give me the cheaper price if

I bought this dress? How about one

hundred and twenty thousand rupiahs?

Seller :

Yang mana ko?

(Which one?)

Buyer :

Iko.

(This one.)

Seller :

Bukan begitu Bu sayang. Ambo terus

terang kalau nak bajualan ndak baduto.

Saratuih ampek puluah ribu. Modal

saratuih dua puluah ribu. Ambiak dua

puluah ribu. Indak baduto. Sebab siko

langganan dah lamo-lamo.

(Let me explain my dearest, Madam…I

am definitely honest to sell. I only get

twenty thousand rupiahs of one hundred

and forty thousand rupiahs I sell to you.

I talk honestly. You can ask the visitors

as they are all my old customers.)

Buyer :

Saratuih tiga puluah ribu yo?

(How about one hundred and thirty

thousand?)

Seller :

Astagfirullahaladzim. Dapek sapuluah

ribu. Belum lai ongkos becak barang.

Ko tanyalah ke urang. Buat mahal ambo

indak pernah. Indak pernah.

(Please forgive me, God. I only get ten

thousand rupiahs for my profit. It is not

even enough to pay for the cart cost.

You can ask other people. I never sell

with the high price. Never.)

Buyer :

Bara haragonya kini?

(So, how much is the final price)

Seller :

Satu ampek ambiaklah.

(It is still one hundred and forty

thousand)

Buyer :

Bara samuanyo?

(How much is the total price?)

Seller :

Duo anam. Minta izin labiah kurang.

(Two hundred and sixty thousand

rupiah.) Please forgive me for the

inconvenience.

Buyer :

Samo-samo.

(So do I)

There are 2 (two) speakers involved in

conversation 2 (two). Both of them are female. The

word Uni expressed by the buyer in the conversation

is referred to an older woman and indicates that the

buyer is younger than the seller. Based on the result

of the in-depth interview and questionnaire which is

treated as supporting data, it is found that both of

them are migrants and come from Bukittinggi. The

buyer has lived in Medan for more than 40 (forty)

years meanwhile the seller has lived in Medan for

more than 60 (sixty) years. The buyer moved to

Medan for family reason, contrastively, they seller

moved for an economic reason. Both still maintain

their local language in their daily life although they

have been living in the city for years.

The result of analysis done on conversation 2

(two) found that there are 4 (four) maxims of

politeness principles represented in the conversation,

namely tact maxim, modesty maxim, generosity

maxim, and approbation maxim, however, the

violations also occur. The beginning of the

conversation illustrates the modesty maxim in which

the seller greets the buyer friendly and politely and it

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1868

makes the buyer is attracted to see her products. The

conversation is continued by the buyer asking for the

price of a long dress and lower price. The seller

answers the buyer's question and also agrees to give a

lower price as the buyer is Minangkabau ethnic. This

situation describes that approbation maxim takes

place in the conversation. However, the buyer does

not want to buy the long dress as it has lace with it.

Nevertheless, the seller patiently gives a reasonable

opinion to ensure the buyer for her choice and it

implicitly shows the tact maxim. The buyer directly

asks the seller the price of another long dress and also

asks for the lower price. The seller answers it but she

does not agree to give a cheaper price and tries to give

an understanding to the buyer. This part of the

conversation indicates that the violation of agreement

maxim occurs because the seller, in this case,

maximizes disagreement between her and the buyer.

The buyer agrees to buy the long dress due to she has

no alternatives for the dress she wanted.

The following conversation describes the buyer who

asks for yellow long dress and begs for the seller

generosity to give a lower price. However, the seller

starts giving strict explanations and reasons which

clearly concludes that she feels reluctant to accept the

buyer's request. In other words, this situation implies

the violation of the maxim of generosity. The buyer

keeps begging for the seller's generosity by

bargaining the price of the yellow long dress she is

interested in, yet the seller refuses her offer by

repeating the word ‘never' which emphasizes that it is

actually the cheapest and final price. Strict opinions

and explanations stated by the seller breaks the

politeness principles as the seller maximizes the

benefit to herself which means as the violation of

generosity maxim. The buyer finally unwillingly

accepts the final price and confirm the total of the

price that she must pay to the seller. This situation

also shows the violation of agreement maxim. The

buyer ends the conversation by telling the total of the

price, however, she also forgives for the

inconvenience. This situation describes the sympathy

maxim because the seller minimizes antipathy

between herself and the buyer, and the buyer responds

to her forgiveness.

Since the seller is older than the buyer, violation of

the maxims of politeness principles are potentially

done by her. It is due to she has more authority to

control the situation. This situation surely has a

relationship to the level of language in which the

seller speaks with kato mandata (the language used to

the younger) whereas the seller must speak with kato

mandaki (the language used to older). This age

difference certainly limits the buyer's power in the

selling and buying process. In other words, it can be

said that the level or types of language used by MK

migrants contribute to the application of politeness

principles as well as the violation during the selling

and buying process.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Based on the analysis done, it is found that the six

maxims of politeness; tact maxim, modesty maxim,

approbation maxim, agreement maxim, generosity

maxim, and sympathy maxim proposed by Leech

(2014) are found in the conversation done between

migrant Minangkabau sellers and buyer in traditional

market during selling and buying transaction.

Furthermore, politeness principles are applied

conditionally; depend on the speakers’ background

involved, especially age and social status which

associate with the language they use (Nan Ampek).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge that the present

research is supported by the Ministry of Research,

Technology and Higher Education of Republic of

Indonesia. The support is under the research grant

TALENTA USU of the Year 2018.

REFERENCES

Arndt, H. & Richard J. Politeness revisited: Cross-modal

supportive strategies. International Review of Applied

Linguistics 23:281-300. 1985.

Arndt, H. & Richard J. Verbal, prosodic, and kinesic

emotive contrasts in speech. Journal of Pragmatics

15:521-549. 1991.

Azrial, Yulfian. 2008. Budaya Alam Minangkabau SD

Kelas 4. Padang: Angkasa Raya.

Brown, P. & Levinson, S. Universals of language usage:

Politeness phenomena. Pp. 56-324 in Questions and

Politeness, edited by E. Goody. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press. 1978.

Brown, P. & Levinson, S. Politeness: Some Universals in

Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. 1987.

Budiarta, I.W., and Rajistha, I.G.N.A., 2018. Politeness in"

Adit dan Sopo Jarwo" Animation. Lingua

Cultura, 12(1), pp.25-30.

Cherry, R.D., 1988. Politeness in written

persuasion. Journal of pragmatics, 12(1), pp.63-81.

Crouch, S. E. (2009). Voice and verb morphology in

Minangkabau, a language of West Sumatra,

Politeness Principles Expressed by Minangkabau Migrants in Traditional Market: A Cultural Pragmatic Study

1869

Indonesia (Doctoral dissertation, External

Organizations).

Drakard, J. 1999. A kingdom of words: Language and

power in Sumatra. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Fraser. Perspectives on politeness. Journal of Pragmatics

14. B. 1990.

Gordon, Raymond G., Jr ed. 2005. Ethnologue: Languages

of the world, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL

International

Grice, P. Logic in conversation. in Syntax and Semantics:

Speech Acts 3, edited by P. Cole & J. Morgan. New

York: Academic Press. 1975.

Hammond, C., 2017. Politeness in Administrative

Discourse: Some Perspectives from Two Institutions in

Ghana. Journal of Universal Language, 18(1), pp.35-

67.

Held, G. (1992) ‘Politeness in linguistic research’, in

Richard Watts, S. Ide, K.Ehlich (eds) Politeness in

language: Studies in its history, theory, and practice,

Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Ide, S. Formal forms and discernment: Two neglected

aspects of universals of linguistic politeness.

Multilingua 8:223-248. 1989.

Jansen, F. and Janssen, D., 2010. Effects of positive

politeness strategies in business letters. Journal of

pragmatics, 42(9), pp.2531-2548.

Jiang, X., 2010. A Case Study of Teacher's Politeness in

EFL Class. Journal of Language Teaching &

Research, 1(5).

Kuntsi, P., 2012. Politeness and impoliteness strategies

used by lawyers in the Dover trial: A case

study. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of

Eastern Finland, Finland.

Kurniawan, C. and Isnanda, R., 2014. Kesantunan

Berbahasa Minangkabau dalam Tindak Tutur Direktif

Anak terhadap Orang yang Lebih Tua di Pauh Kamang

Mudiak Kecamatan Kamang Magek Kabupaten

Agam. Abstract of Undergraduate, Faculty of

Education, Bung Hatta University, 3(7).

Lakoff, R. The limits of politeness: Therapeutic and

courtroom discourse. Multilingua 8:101-129. 1989.

Lakoff, R. Talking power. New York: Basic Books. 1990.

Leech, G. Principles of Pragmatics. Essex: Longman. 1983.

Leech, G. (2014). The Pragmatics of politeness. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Liu, F., 2012. A Study of the principle of conversation in

advertising language. Theory and Practice in Language

Studies, 2(12), p.2619.

Scollon, R & Scollon, S. Intercultural Communication.

Malden: Blackwell. 2001.

Shahrokhi, M. and Bidabadi, F.S., 2013. An overview of

politeness theories: Current status, future

orientations. American Journal of Linguistics, 2(2),

pp.17-27.

Spencer-Oatey, H. Rapport Management: A framework for

analysis. in Culturally speaking: Managing rapport

through talk across cultures, edited by H. Spencer-

Oatey. London: Continuum. 2000.

Watts, R. Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. 2003.

Watts, R. Linguistic politeness research. In Politeness in

language: Studies in its history, theory, and practice,

edited by R. Watts, S. Ide, & K. Ehlich. Berlin: Mount

De Gruyter. 2005.

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1870