Perception and Utilization of Urban Corridor as Public Space in

Medan, Indonesia

Wahyuni Zahrah

1

, Achmad Delianur Nasution

1

, and Novi Rahmadhani

1

1

Department of Arcitecture, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia

Keywords: public space, urban corridor, perception, Medan, Indonesia

Abstract: The paper discuss the perception and utilization of street corridors as a public space. The study took place in

three commercial corridors in Medan. They are Asia Corridor, Kapten Muslim Corridor, and Ring Road

Corridor. The objective of the study is to explain and explore the planning and design process, the physical

quality, the perception of the users, and the utilization of the corridors. The interview with the Government

of Medan was carried out to get the information about the process of urban corridors planning and design.

The physical quality of the corridor was mapped and recorded through a visual survey. The surveyors

interviewed the users to collect the facts about the intensity of the activity and people perception of the

corridors. The analysis used mix method that consisted of qualitative and quantitative data. The study found

that the corridors were not planned in a detailed guideline by city government. The utilization was driven by

user’s initiatives, both the building owners and the street vendors. The corridors was not functioned

optimally as public space due to the lack of facility and quality. In general, people thought that it is not

allowed to use public space for street vending and vehicles parking area. However, they do not have any

proper choice in the urban space to meet their needs, so they use the urban public space individually.

1 INTRODUCTION

There are several types of public open space, such as

parks, squares, space between buildings, and streets.

In the past researches the authors have explored the

public life of parks and squares in Medan and other

towns in Sumatera Utara province. The investigation

showed that the using of the public spaces was

intensive, while the quality of the design was not so

good (Nasution dan Zahrah, 2015). However, the

parks and squares cannot be found easily, due to the

lack of land-availability for public use. There is a

kind of other public open space that always exist in

the urban area: the street. The street is a linear-form

public open space. The row of buildings along the

street shape a corridor and accommodate people

activities (Zahrah et al, 2016; Zahrah and Lie, 2016).

A corridor is more than just a circulation path. It

can be a community space where people engaged

(PPS, 2008). An urban corridor, which consists of

front yard of buildings, pedestrian path, green path

and streetscape, can be a melting point for

community to interact each other. Some studies

investigated the utilization of street corridor in

Indonesia based on several point of views.

Widjajanti (2016) analyzed the characters of space

occupied by street vendors in a corridor of an

education area. Uniaty (2017), that reviewed a street

in Northern Jakarta, highlighted the importance of

considering the street users. Darmoyono and Tanan

(2017) stressed their study to community

participation in corridor planning and design. To the

best knowledge of the authors, there is no study

about how people view the corridor in relation with

its actual quality and their needs, especially in

Medan, Indonesia. It is necessary to explore how the

urban space, shop houses corridor in this case, being

planned, perceived and used by people. Thus, it can

be understood the way people occupying the urban

space. This study would be a reference to respond to

local people needs in the urban planning and design

process.

2 METHOD

The study was located in three shop houses corridors

in Medan, Indonesia. The corridors were Jalan Asia,

Jalan Kapten Muslim, and Ring Road. Jalan Asia

346

Zahrah, W., Nasution, A. and Rahmadhani, N.

Perception and Utilization of Urban Corridor as Public Space in Medan, Indonesia.

DOI: 10.5220/0010095903460350

In Proceedings of the International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches (ICOSTEERR 2018) - Research in Industry 4.0, pages

346-350

ISBN: 978-989-758-449-7

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

was the oldest corridors, while Ring Road was the

newest construction.

This research was a descriptive exploratory study

since it means to explain and explore how the

corridors planned, perceived and used. The data

collected was qualitative and quantitative. The

planning and design process of the corridors was

investigated through the interview with Medan

Government, as well as the interview with corridors’

users and field observation. The physical quality of

the urban space was collected by using the visual

survey method. The surveyors mapped and recorded

the related elements, such as site plan, pedestrian

path, and street furniture. The intensity of utilization

was identified through the questionnaire. There were

189 respondents that found in the corridors and

agreed to participate in the survey. They were

chosen randomly along the corridor by considering

their activities, such as the pedestrians, the street

vendors, the customers of shop house and street

vendors, and the shop houses owners. The interview

to users was carried out to explore how they

perceived and used the space. The way they used the

urban space was recorded through behavioural

mapping, based on the photographs, observation, on-

site sketching, and video recorder.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The results will be discussed based on variables that

studied. They are the planning and design process of

corridor, the physical quality, the users perception,

and the way people use the corridor.

3.1 The Design and Planning Process of

the Corridor

Based on the interview to the official of Dinas

Perumahan Kawasan Pemukiman dan Penataan

Ruang (Housing, Settlement and Urban Design

Services) of Medan Municipality, it can be

concluded that the City Government did not have

and implement the detailed planning of the corridor

that could guide the design and control the growth.

The existing regulation was a general plan that

regulates the urban space in two dimensions, such as

building setback, and building coverage. There was

no regulation to manage and determine the building

frontage and mass, the pedestrian performance, the

vegetation arrangement and the land function. As a

consequence, the corridor grew spontaneously

without control, following the individual needs. The

field survey showed that the building owners did not

always obey the regulation of the setback and

building coverage. In one area the buildings had a

setback, while in the other area was adjacent to the

sidewalk.

Figure 1. The quality of the corridor: pedestrian path

obstruction by signage and parking

3.2 People’s Perception to Corridor

Perception is one of the significant parts in the urban

design. By recognizing the people perception, their

needs can be identified well (Carmona, 2004;

Nasution and Zahrah, 2014). The study tried to

investigate people perception of the corridor by

asking the users. Most of respondents were males,

(63.49 %), productive age (18 – 45, 87.31 %),

entrepreneur (35.98 %), married (50.26 %), owning

private vehicles (84.13 %) and use their vehicles as

the transportation mode (79.90 %) (Table 1).

Table 1. Respondents’ characteristics

Gende

r

a. Female

36.51%

b

. Male

63.49%

Ag

e

a. 18 - 25

35.98%

b

. 26 - 35

26.46%

Perception and Utilization of Urban Corridor as Public Space in Medan, Indonesia

347

c. 36 - 45

24.87%

d. 46 - 55

9.52%

e. 56 - 65

3.17%

f. > 65

0%

J

ob

Entrepreneu

r

35.98%

Government emplo

y

ee

15.87%

Governmen

t

-corporate

emplo

y

ee

7.94%

Private emplo

y

ee

8.47%

Professional/self-employee

1.59%

Others

30.16%

M

arital Status

a. Marrie

d

50.26%

b

. Not marrie

d

49.74%

M

onthl

y

expenses (million IDR)

a. < 5

58.73%

b

. 5 - 10

29.63%

c. 10 - 15

10.05%

d. 15 - 20

1.59%

e. 20 - 25

0%

f. > 30

0%

Do you have private vehicles?

a. Yes, motor cycle

59.26%

b

. Yes, automobile

24.87%

c. nothin

g

15.87%

What is the transportation mode you

use?

a. motor c

y

cle

55.56%

b

. automobile

24.34%

c. public transpor

t

9.52%

d. Online -

p

ublic

motorcycle

4.76%

e. Online taxi

3.17%

f. Trishaw

0.53%

g

. Walkin

g

2.12%

With the low physical quality of the corridors,

particularly if compared to the good urban corridor

standards (PPS, 2008), and the needs to public life

rather than public space (Banerjee, 2001), the

majority of respondents perceived the corridor as

‘good’ or ‘very good’, mainly at the aspects of

security, cleanliness, night lighting, traffic,

liveliness, and comfort. Meanwhile, the shade of

trees and the attractiveness factors were perceived as

‘not good’ (Table 2). As the security and comfort

became the crucial consideration they needed

(Crewe K, 2001), the respondents used the space for

their needs, though the quality of the corridor was

not good enough. The conditions seemed relating to

the activities occurred. In the study area, the optional

or recreational activities were rarely found, which

connected to the quality of the place (Gehl, 2002).

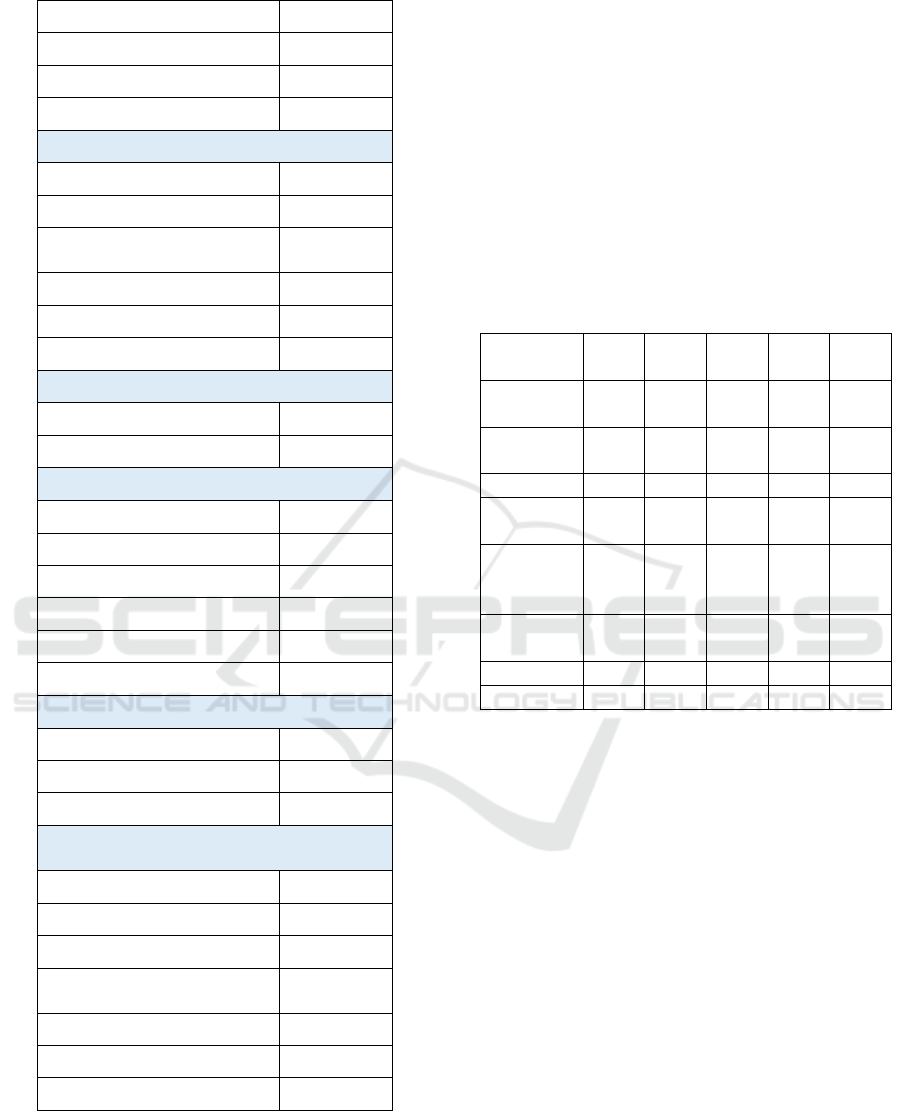

Table 2. People perception of the quality of corridors

Variables very

goo

d

good Less

goo

d

bad Very

b

a

d

Security 4,8 38,2 38,2 2,4 0

Cleanline

ss

0,9 54,6 35,3 8,7 0,5

Li

g

htin

g

5,3 66,7 22,2 5,3 0,5

Shady

trees

7,3 38,2 36,7 15,5 1,9

Beauty/at

tractivene

ss

1,5 27,5 49,3 19,3 2,4

Livelines

s

17,4 72,9 9,7 0 0

Traffic 5,3 55,6 33,9 4,4 0,9

Comfor

t

3,0 62,6 30,3 3,5 0,5

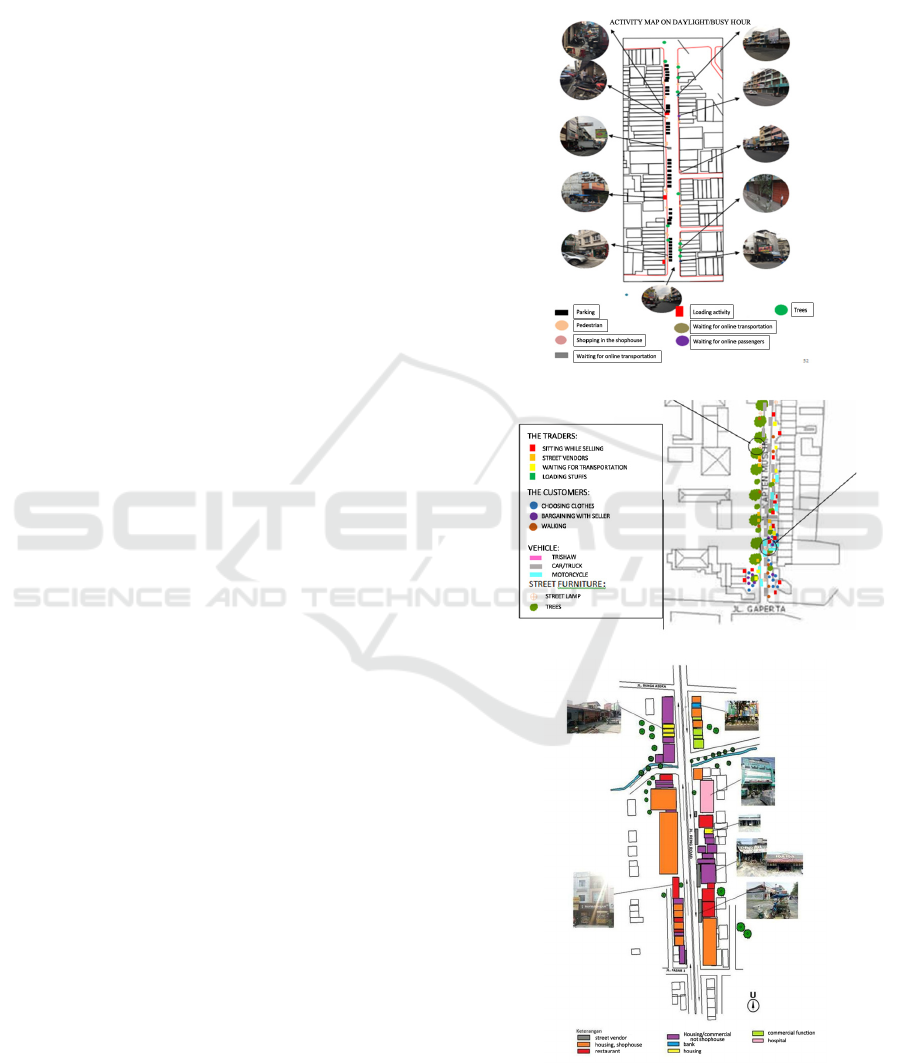

3.3 The Way People using the Corridor

The land use in the shop houses corridor was mostly

commercial function, such as retails, restaurants, or

services purpose. ‘Ruko’ as the acronym of ‘rumah’

(house) and ‘toko’ (shop) did not always present in

all corridor, except in the oldest Area of Jalan Asia.

The new shop houses, such as in Ring Road

Corridor, was only functioned as commercial uses,

not as a house where the family stayed and lived.

The owners or the tenants of the buildings,

particularly in Kapten Muslim and Ring Road

Corridors, lived in the other buildings, not in the

‘shop houses’. In this area, we could find the largest

portion of the empty shop house, the buildings

without occupants. In contrast, most of the shop

houses in Jalan Asia was functioned as a ‘shop’ and

also as a ‘house’. However, the newer the corridor,

the larger activities occurred. Jalan Kapten Muslim

Corridors was the liveliest zone compare to the two

other corridors. In here, street vendors operated from

morning until night. We could see that at the street

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

348

vendor spots along the corridors, the community

activities took place. The condition related to the

lack of communities’ facility along the pedestrian

path; there was no comfort spacious side walk or

benches. Meanwhile, the informal traders provided

sitting place and food. In this place people interacted

each other, at least between customers and the

tradesmen. In the other part of corridor, including

the pedestrian way, it was very rarely people

walked. It might correlate with the facts that the

majority of people was the vehicles-dependence

community, more than 80 % of them did not walk,

but used their private vehicles, mostly motorcycles.

Nevertheless, the interview with the pedestrians

showed that they ever said greeting to the other

people while walking. This fact indicated that

walking could stimulate interaction and social

contact. Since it was very rarely to find people walk,

the interaction happened in the street vendor’s

points.

How the vendors used the space? There was no

regulation or convention. They just came, chose a

location, and the place became ‘theirs’. The

favourite place was the shady spot under the tree. In

some cases, the vendors bargained with the building

owners to use the space in front of the building,

including the sidewalk and street, a part of public

space that should be ‘not for sale’. They put their

equipment in the buildings’ front yard, and or on the

pedestrian path, and or on the street’s boundary.

They sold something, having repeated customers,

and did not want to move from the place. The

vendors also said that their activities did not injure

the pedestrians, nor the traffic. This condition was

different with customers’ opinions. They said that

they knew it is not allowed occupying pedestrian

path for parking.

“... We place the stalls on the street, cashier, and

benches for customers on the sidewalk... we use only

as wide as one lot of a shop house.... ” (R, street

vendor in Jalan Asia)

“... We choose the shady place under the tree... it is

safe and secure here, never happens a crime ... we

don’t want to move from here. It has been a long

time we trade, it is the only our income resource...

“(A, street vendor in Jalan Kapten Muslim)

The other utilization of the urban space in the

corridor was the parking lot (Figure 3). Since the

buildings had no setback, and the presence of the

informal merchants on the sidewalk and or the edge

of the street, there was no allocation lot for parking.

As a result, the sidewalk – which was very rarely

being used by the pedestrians – was occupied by

cars or motorcycle for parking. The fact was contrast

with their most opinion that “agree that parking on

the pedestrian path injures the pedestrians” and

“agree that parking on the street bothers the traffic”.

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

Figure 2. Activities in the corridors (i) Asia (ii) Kapten

Muslim (iii) Ringroad

Perception and Utilization of Urban Corridor as Public Space in Medan, Indonesia

349

Figure 3. The occupation of the corridor: parking and

street vendor

4 CONCLUSIONS

The study showed that there was a gap between the

community’s knowledge and their practical in using

the urban space, the urban corridor in this case. They

knew about how the space should be used as a

public space, but there was no choices to fulfill their

needs, mostly for the economic interest and the

‘vehicle-dependence trap’. Furthermore, there was

no proper plan and design to accommodate and

anticipate the dynamics of the urban community.

The urban corridor seemed to be ‘a container of

vehicles and stalls’, rather than a public space,

where people engage in a mutual interaction. The

urban space was failed to provide the demand. These

findings confirmed the other researches that the

main problems in the urban corridor was the lack of

appropriate pedestrian path and the ‘attack’ of

vehicles and street vendors (Zahrah et al, 2016;

Tanan, 2017) because of the absence of the good

design, the weakness of regulation control, and the

shortage of community’s awareness. Since the

respondents of the survey were the people found in

the corridors, the study just describes the perception

based on them. It is much recommended to continue

this study by a household survey, so that it could be

obtained a more comprehensive picture of people

perception about the utilization of the corridor,

particularly in Medan, Indonesia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge that the

present research is supported by Ministry of

Research and Technology and Higher Education

Republic of Indonesia. The support is under the

research grant DRPM Kemenristekdikti of Year

2018 Contract Number 90/UN5.2.3.1/PPM/KP-

DPRM/2018.

REFERENCES

Banerjee T. 2001. The future of public space: Beyond

invented streets and reinvented places. Journal of the

American Planning Association vol 67 no. 1 : 9-24

Carmona M, 2004 Public Places Urban Spaces Oxford:

Elsevier and Architectural Press

Crewe K , 2001. Linear parks and urban neighborhoods: A

case study of the crime impact of the Boston South-

west corridor. Journal of Urban Design Vol 6 no. 3:

245 – 264

Gehl J 2002 Public Space and Public Life City of

Adelaide. City of Adelaide

Nasution AD, Zahrah W, 2014. Community perception on

public open space and quality of life in Medan.

Indonesia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

153: 585-594

Nasution AD, Zahrah W 2015. Urban Design Guidelines

for Shophouse: A Temperature Modificaion

Approach. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences

179: 308-317

Tanan N, Darmoyono L. 2017. Achieving walkable city in

Indonesia: Policy and responsive design through

public participation. AIP Conference Proceedings

1903(1):080010 (2017) doi: 10.1063/1.5011598

Uniaty Q. 2017. Pedestrian Space Characteristics Analysis

on Kyai Tapa-KH Hasyim Ashari Street Corridor,

West Jakarta. Aceh International Journal of Science

and Technology 6 (3): 153-165

Widjajanti, 2016. The Space Utilization by Street Vendors

Based on the Location Characteristics in the Education

Area of Tembalang, Semarang. Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences 227 : 186 – 193

Zahrah, W, Aulia, DN, Marpaung, Beny OY. 2016.

Koridor Ruang Kota Layak Huni: Budaya

“Merampas” Ruang Publik? Prosiding Temu Ilmiah

2016 IPLBI : E 081-088

Zahrah, W, dan Lie, S., 2016, People and urban space in

Medan: an environment behaviour approach.

Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal Vol 1

Issue 1 368-374

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

350