The Experiential Meaning in Forensic Courtroom Discourse

T. Silvana Sinar

1

, T. Thyrhaya Zein

1

, Nurlela

1

and Muhammad Yusuf

1

1

English Literature Department, Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia

Keywords: Forensic Linguistic, Courtroom Discourse, Systemic Functional.

Abstract: As a part of forensic linguistics, courtroom discourse is crucial to be explored. This paper is an attempt to

investigate the experiential meaning focused on process types in courtroom discourse based on Halliday’s

systemic functional grammar. Descriptive qualitative method focused on content analysis was employed as

the research design. The data were the clauses taken from the conversation between jury, witness, and public

prosecutor in a courtroom discourse in Medan-Indonesia. The findings reveal that material process is the

dominant among other processes totalling to 33.07% followed successively by verbal (20.47%), mental and

relational process (16.54%). It means that the interaction in courtroom discourse explores more about what

happened in the case and what has performed by the actor or defendant. The speaker employs material process

‘to deliver’, action of corruption done implicitly, while verbal process is used to cover his worries of being

known as corruptor.

1 INTRODUCTION

Language of law is able to be utilized as evidence in

forensic linguistics (FL). Fuzer and Barros (2009)

assert that a challenge is exactly presented by legal

language through its complexity and technicality to

the people who are concern on the legal practitioner

education. Rodrigues (2005) argues that rules cover

many areas in social life. Furthermore, the law

language is regarded as having specific

characteristics (Strębska-Liszewska 2017). The

utilization of language in courtroom discourse is one

of the main areas of FL (Coulthard & Johnson 2007;

Olsson 2004; Wang 2012).

Fundamentally, systemic functional linguistics

(henceforth SFL) is beneficial to analyze and explain

how meanings are made in everyday linguistic

interactions. Almost any area of linguistics can be

relevant in court (Tiersma & Solan 2002) and

language use was taken place in legal process (Sadiq

2011). Then, SFL also iews that language possesses

three simultaneous meanings regarded as

metafunctions (Sinar 2007). Metafunctions are

divided into the ideational; to represent the

experiences, the textual; to link or organize the

experiences, and the interpersonal; to exchange the

experiences. Moreover, the ideational is divided into

two categories, they are experiential function and

logical function; those which realize the function of

clause as representation and communication. That is

why the ideational meaning is regarded the

representation of clause and its realization is through

transitivity system covering process type. This can be

used in analyzing courtroom discourse as the

following examples.

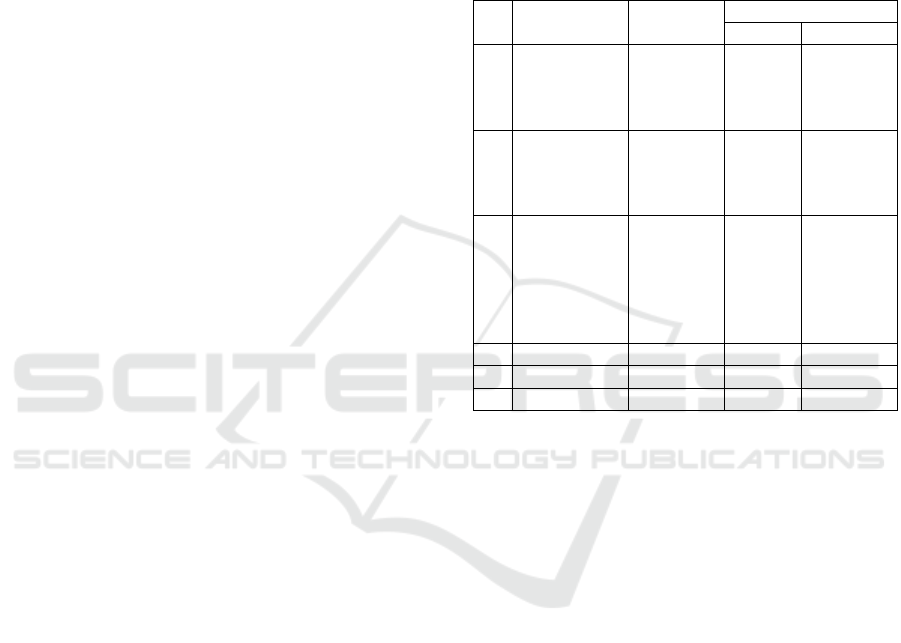

Table 1: Jury’s statement.

Kalau proyek lanjutan

peningkatan ruas jalan pasar

8 kecamatan Air Putih

sudah tau ?

About the continuity of the

improvement of road at pasar

8 district Air Putih

Have (you)

known?

Phenomenon Process; mental

Table 2: Witness’ statement.

si abun Sebenarnya menitipkan 230

juta

Abun trully deposited 230 M

Actor Process;

material

Goal

Those utterances are taken from jury and witness’

statement in courtroom discourse. Then, the

representation of mental process ‘sudah tau’ or have

Sinar, T., Zein, T., Nurlela, . and Yusuf, M.

The Experiential Meaning in Forensic Courtroom Discourse.

DOI: 10.5220/0010084915011505

In Proceedings of the International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches (ICOSTEERR 2018) - Research in Industry 4.0, pages

1501-1505

ISBN: 978-989-758-449-7

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

1501

known in Jury’s statement is used to explore the

involvement and the knowledge of the witness about

the case. Then, material process is used by witness

through the word ‘menitipkan’ or deposit to express

that he did something. The system of transitivity has

a purpose to explain how an action is done through

various kinds of processes.

There are many studies conducted in the area of

forensic linguistic and courtroom discourse. Stroud

(2012) sees activity in courtroom discourse

specifically on the participants’ changing role,

Susanto (2016) in his study provides the examples of

some language aspects applied in the courtroom, and

then, Matin and Rahimi (2014) highlight the use of

forensic discourse analysis to interpret and analyze

legal context. Those previous research has some

differences from this paper. Therefore, this paper is

intended to investigate experiential meanings in

courtroom discourse. To do this, the theory of

transitivity analysis described by Halliday and

Matthiessen (2014) was employed.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Forensic Linguistics (FL) and

Courtroom Discourse

Jordan (2002) states that FL is defined as one of

applied linguistics branches or forensic sciences. It is

also supported by Pádua (2012) claiming that FL

deals with the concern on the use of language inside

legal contexts and the legal phenomena. Another

expert also argues that the research in the area of

discourse in courtroom may cover many aspects such

as testimony, opening and closing statements, etc

(Dong 2013).

2.2 Systemic Functional Linguistics

(SFL)

This theory has a close relation to the texts and

context (Sinar 2018) and it is utilized for construing

human experiences and looking into the working of

language within social context (Naz, Alvi & Baseer

2012). Another expert also argues that it also provides

a study the interrelationship between language, text

and the contexts (Lirola 2012). Three different levels

of meaning are covered in metafunctions namely

ideational function, interpersonal function, and

textual function.

2.3 Transitivity System

Transitivity system elucidates the process as the

realization of experience (Halliday 1994). Then, it is

also related to the process type choice and the

participants’ role realized into reality experiences

(Eggins 2004). Halliday and Matthiessen (2004)

divide process types as illustrated in table 3.

Table 3: Types of process in transitivity system.

N

o

Types of

Process

Meaning Participants

I II

1. Material:

- Action

- Event

“doing”

“doing”

“happening

”

Actor Goal

2. Mental

- Perception

- Affection

- Cognition

“sensing”

“seeing”

“feeling”

“thinking”

Sensor Phenomen

on

3. Relational

- Attribution

- Identificati

on

- Possession

“being”

“attributing

”

“identifyin

g”

“having”

Token

Carrier

Identifie

d

Possess

or

Value

Attribute

Identifier

Possessed

4. Behavioural “behaving” Behaver -

5. Verbal “saying” Sayer Target

6. Existential “Existing” Existent -

3 METHOD

This study applied descriptive qualitative method

focused on FL analysis on courtroom discourse. The

analysis was based on SFL including metafunctions

constructed ideationally through the transitivity

choices of the process types of jury, witness, and

public prosecutor in a trial stage in Medan. To carry

out the research, some transcribed text of interaction

among jury, witness, and public prosecutor in a trial

stage was selected as the source of data. There are 127

clauses were analyzed. Firstly, each clause was

analyzed, then the process was categorized, next the

transitivity was analyzed based on type of process.

After that, the types of processes were ranked based

on the result of the analysis. Finally, the conclusion

was drawn based on the analysis.

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1502

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Results

It is discovered that five kinds of process appeared in

the courtroom discourse containing the interaction

between jury, witness, and public prosecutor. The

detail of the distribution is illustrated in table 4.

Table 4: Process distribution.

No. Process Occurrences %

1 Material 42 33.07

2 Mental 21 16.54

3 Relational 21 16.54

4 Behavioural 0 0.00

5 Verbal 26 20.47

6 Existential 17 13.39

Total 127 100

The table elucidates that the material process is

the dominant one among the processes whereas the

verbal, material, relational, and existential,

respectively follow the material process; although, as

far as frequency is concerned. In contrast, behavioural

process did not occur in the data.

4.2 Discussion

The interaction in the courtroom discourse reveals

that material process is most frequently used among

other processes and the interaction describes that

material process dominantly occurs and it is followed

by three other processes, mental, relational, verbal

and existential. This analysis implies that corruption

act is closely related to the actor (who), place (where),

and the goal (what), as represented in the following.

Clause 10

Jury: Kemudian CV Jodi dipergunakan oleh

Sucipta Abun dalam proyek peningkatan ruas jalan

komplek 126 Kompi C Tanjung Kaso Kecamatan Sei

Suka (Then, CV Jodi was used by Sucipta Abun in a

project of road improvement of area 126 block c

Tanjung Kaso districts Sei Suka).

Clause 11

Witness: iya (yes)

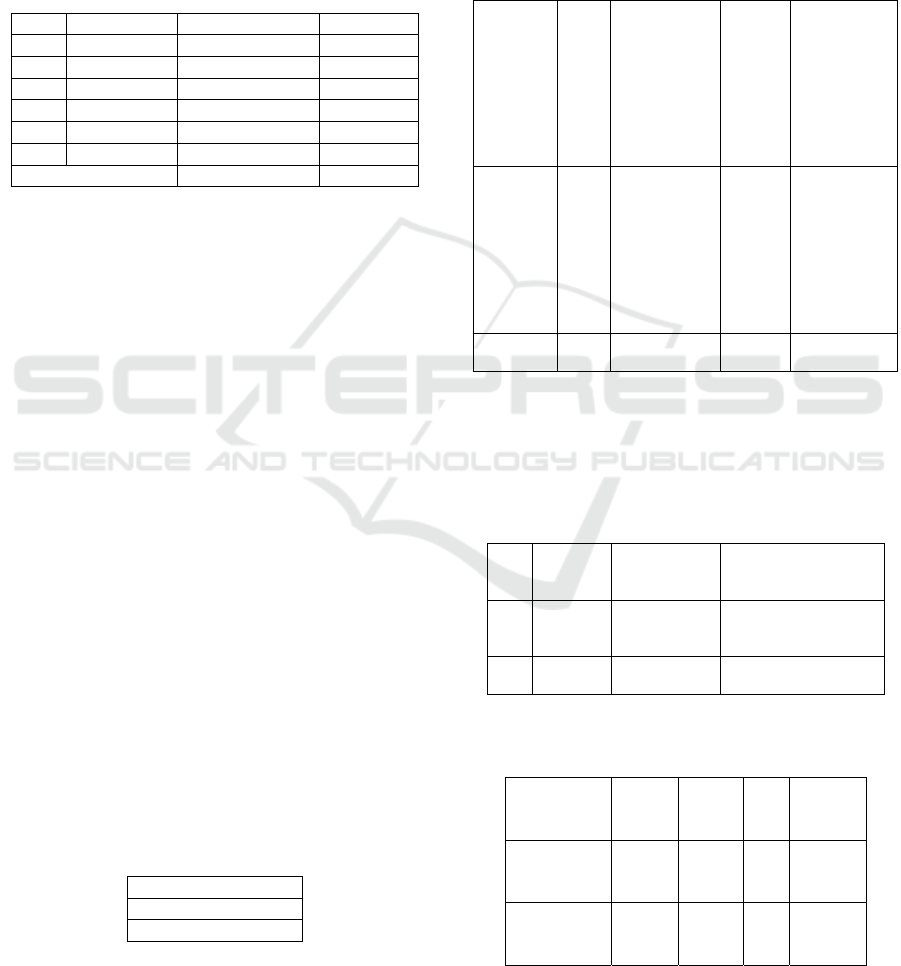

Table 6: Witness’ response.

iya

y

es

-

The clauses 10 and 11 illustrated the interaction of

the jury and the witness. It contains material process

‘dipergunakan’ or ‘used’. The jury emphasised by

delivering material process that the actor performed

or did something about the project case and the actor

is involved. The witness then replied with a minor

clause ‘yes’ to confirm the statement. This is also

relevant to research conducted by Bartley (2017)

proving that material (action) process is dominantly

utilized in the courtroom discourse.

Table 5: Clause containing material process.

kemudian cv

jodi

dipergunakan oleh

Sucipta

Abun

dalam

proyek

peningkatan

ruas jalan

komplek 126

kompi c

tanjung kaso

kecamatan

s

ei suka..

Then CV

Jodi

was used by

Sucipta

Abun

a project of

road

improvement

of area 126

block c

Tanjung

Kaso

districts Sei

Suka

Goal Process:

Material

Actor Circ; place

Clause 29

Jury: Ini saudara menyebutkan uang tersebut

jumlahnya 240 juta, ya (You mentioned that the

money is totalling to 240 millions, right.

Table 7: Clauses containing verbal process.

ini saudara menyebutkan uang tersebut

jumlahnya 240 juta,

ya?

this You mentioned mentioned that the

money is totalling to

240 millions, right?

Sayer Process:

verbal

Verbiage

Table 8: Clauses containing relational process.

harusnya, tapi 240

juta,

iya tapi

(it) should

be

but 240

M

yes but

Process;

relational

- Value - -

The Experiential Meaning in Forensic Courtroom Discourse

1503

Clause 30

Witness: harusnya, tapi 240 juta, iya tapi…(It

should be, but,… 240 M, yes, but…….)

Clauses 29 and 30 show the interaction between

the jury and witness. The clause explained in the table

7 shows the use of verbal process. This process

respectively followed material process as the

frequently used process. Verbal process is used to

signal the process of saying. The jury used verbal

process to clarify witness’ statement about the

amount of the money totalling to 240 millions. Then,

the jury tried to explore the details and the witness’

honesty and remind the witness based on what has

been stated in police investigation report. This makes

sense since Waskita (2014) argues that FL entails

gaining truth and honesty, and who was speaking and

its purpose can be guessed. In the trial stage, the jury

and the witness were involved in the interaction. They

also used relational process (clause 30) to signal the

process of ‘being’ and to identify token and value.

Then, mental process (clause 14 and 15) was also

represented in the utterances. The mental process

explains what actually occurs in the internal world of

the mind (Suhadi 2012).

Clause 14

Jury: tau saudara, yang dipakai abun yang ini?

(Do you know it is used by Abun?)

Table 9: Mental process used by jury.

tau saudara yang dipakai

yang ini

abun

Do (…..) know (you) it is used By

Abun

Process: mental vocative Phenomenon senser

The jury tried to explore the memory of the

witness by expressing the word ‘know’. This then was

replied by the witness through the expression ‘saya

tau cuma 2’ (I know only 2). This means that the

witness actually acknowledges about the information

stated by the jury.

Clause 15

Witness: saya tau cuma 2 (I know only 2)

Table 10: Mental process used by witness.

Sa

y

a tau cuma 2

I know onl

y

2

Senser Process:

mental

Phenomenon

In courtroom discourse specifically corruption

case, it can be interpreted that even though there are

some codes or symbols, the indication of the

existence of money transaction is realized by actor

and goal, the place is realized by circumstance, and

the use of process is utilized in order to deceive the

meaning. Then, text and context should be

harmonious since the function of language is to

convey meaning. Language is regarded as semiotic

system which has form, meaning, and realization as

asserted by Halliday and Matthiessen (2014).

5 CONCLUSION AND

SUGGESTION

The experiential meaning analysis through

transitivity presents that material process becomes

frequently used that characterizes the courtroom

discourse totalling to 33.07% followed successively

by verbal (20.47%), mental and relational process

(16.54%). It means that the interaction between jury,

witness, and public prosecutor discussed more about

what happened in the case and what has performed by

the actor or defendant and the speaker employs

material process ‘to deliver’, action of corruption

done implicitly, while verbal process is used to

accomplish his worries of being known as corruptor.

It is also suggested for further research to explore the

courtroom discourse based on other sub-field of

linguistic such as syntax, semantics, and pragmatics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The writers would like to express appreciation to The

Ministries of Research, Technology and Higher

Education of Indonesia for funding the research grant

no 121/UN5.2.3.1/PPM/KP-DRPM/2018.

REFERENCES

Barley, LV 2017, Transitivity, no stone left unturned:

introducing flexibility and granularity into the

framework for the analysis of courtroom discourse,

dissertation, Granada, Universidad de Granada, viewed

31 July 2018.

Coulthard, M & Johnson, A 2007, An introduction to

forensic linguistics: language in evidence, Routledge,

London.

Dong, J 2013, ‘Interpersonal metaphor in legal discourse:

modality in cross-examinations’, Journal of Language

Teaching and Research, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 1311-1321,

viewed 31 July 2018, doi:10.4304/jltr.4.6.1311-1321

Eggins, S 2004, An introduction to systemic functional

linguistics, Continuum, New York.

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1504

Fuzer, C & Barros, NS 2009, ‘Accusation and defense: the

ideational metafunction of language in the genre

closing argument’ in C Bazermen, A Bonini & D

Figueiredo, Genre in a changing world, ParlorPress,

Indiana, pp. 78-96.

Halliday, MAK 1994, An introduction to functional

grammar, 2nd edn, Edward Arnold, London.

Halliday, MAK and Matthiessen C M I M 2004, An

introduction to functional grammar, 3rd edn,

Routledge, London.

Halliday, MAK & Matthiessen, CMIM 2014 An

introduction to functional grammar, 4th edn,

Routledge, London.

Jordan, SN 2002, Forensic linguistics: the linguistic analyst

and expert witness of language evidence in criminal

trials, master thesis, California, Biola University,

viewed 30 July 2018.

Lirola, MM 2012, ‘Exploring the image of women to

persuade in multimodal leaflets’, Theory & Practice in

English Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 27-55, viewed 30 July

2018.

Matin, SA & Rahimi, A 2014, ‘Forensic discourse analysis:

legal speech acts in legal language’, Language Related

Research, vol. 4, no.4, pp. 152-172, viewed 29 July

2018.

Naz, S, Alvi, SD & Baseer, A 2012, ‘Political language of

Benazir Bhutto : a transitivity analysis of her speech

‘democratization in pakistan’’, Interdisciplinary

Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, vol. 4,

no. 8, pp. 125-141, viewed 29 July 2018.

Olsson, J 2004, Forensic linguistics: an introduction to

language, crime and the law, Continuum, London.

Pádua, JP 2012, ‘Norm-enacting activity as on object of

study in forensic linguistics: propositions and first

impressions’, Proceedings of the international

association of forensic linguists’ tenth biennial

conference, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 104, viewed 30 July 2018.

Rodrigues, CCC 2005, Contributos Para A Análise Da

Linguagem Jurídica E Da Interacção Verbal Na Sala

De Audiências, dissertation, Coimbra, University of

Coimbra, viewed 30 July 2018.

Sadiq, MT 2011, A discourse analysis of the language of

interrogation in police/criminal investigations in the

kano metropolis, master thesis, Zaria, Ahmadu Bello

University, viewed 30 July 2018.

Sinar, TS 2007, Phasal and experiential realizations in

lecture discourse: a systemic-functional analysis,

Koordinasi Perguruan Tinggi Swasta Wilayah- I NAD-

Sumut, Medan.

Sinar, TS 2018, ‘Functional features of forensic corruption

case in Indonesia’, The 1st annual international

conference on language and literature, KnE social

sciences, vol. 2018, no. 1, p. 66, viewed 30 July 2018,

doi: 10.18502/kss.v3i4.1919

Strębska-Liszewska, K 2017, Epistemic modality in the

rulings of the american supreme court and polish sąd

najwyższy a corpus-based analysis of judicial

discourse, dissertation, University of Silesia, Katowice,

viewed 30 July 2018.

Stroud, N 2012, ‘Non-adversarial justice: the changing role

of courtroom participants in an indigenous sentencing

court’, Proceedings of the international association of

forensic linguists’ tenth biennial conference, vol. 1, no.

1, p. 115, viewed 30 July 2018.

Suhadi, J 2012, Introduction to English Functional

Grammar, Islamic University of North Sumatra,

Medan.

Susanto 2016, ‘Language in courtroom discourse’,

Proceedings of the fourth international conference on

education and language (4th ICEL), vol. 1, no. 1, p. 26,

viewed 30 July 2018.

Tiersma, P & Solan, LM 2002, ‘The linguist on the witness

stand: forensic linguistics in american courts’,

Language, vol. 78, no. 2, pp. 221-239, viewed 31 July

2018.

Wang, ZH 2012, Forensic Linguistcs. Collected Works of

J.R. Martin, 8th edn, SJTU Press, Shanghai.

Waskita, D 2014, ‘Transitivity in telephone conversation in

a bribery case in Indonesia : a forensic linguistic study’,

Jurnal Sosioteknologi, vol. 13, no. 2, viewed 31 July

2018.

The Experiential Meaning in Forensic Courtroom Discourse

1505