Conservative and Innovative Form of Proto Malay in Malay Asahan

Dwi Wida

y

ati

1

, Gustianin

g

sih

1

, Rosliana Lubis

1

1

Departement of Sastra Indonesia

Faculty of Cultural Science, Universitas Sumatera Utara,

Jl. Universitas No. 19 Kampus USU, Padang Bulan Medan 20155, Indonesia

Keywords: Conservative, Innovative, Vocal, Consonant, Proto Malay, Asahan.

Abstract: This paper aims to describe the innovative and conservative forms of Proto Malay (PM) in Malay Asahan

(BMA) through its reflexes. These forms include vowel and consonant phonemes. The method is a

comparative historical method with the probability theory of language change. From the analysis it is

concluded that the vowels are generally reflected in an innovative rather than consonant. Innovative reflexes

on the vowels cause the reflected lexicons to be innovated. The high vowel /*i/ is reflected into /i/ and /e/.

Meanwhile the vowel /*u/ is split into /u/ and /ɔ/. The middle vowel /*ә/ is reflected into /a /and /ɔ/

innovatively. The vowels /*a/ and /*ә/ simultaneously merge into /a/. Innovatively reflected consonants are

found in /*h/, /*k/, /*ʔ/, and /*r/ consonants. The plosive voiceless consonants /*p/, /*t/, and /*k/ are reflected

at all positions linearly. Meanwhile, the /*c/ consonant appears only in the initial and medial positions, and

/*ʔ/ only appears in the final position. The plosive voiced consonants i.e /*b/, /*d/, /*j/, and /*g/ are only

reflected in the initial and medial positions linearly. The nasal consonants /*m/, /*n/, and /*ŋ/ are also reflected

in all positions linearly, but /*ɲ/ is reflected only in initial and medial positions. The liquid consonant /*r/ and

/*l/ and fricative /*s/ and /*h/ are reflected in all positions. /*r/ consonant is innovated into /R/, while /h/ is

split into /h/ and /Ø/.

1 INTRODUCTION

Asahan Malay (BMA) in its development has a

relationship with the parent language, namely the

Protoaustronesia language (PAN). As a proto

language that covering the Austronesian language

family, PAN language inherits a number of lexicon in

its derivative language. However, after separating

from the parent language, evolutively every language

evolves even in its own way in accordance with its

environment (Bynon, 1979). Evolving and changing

a language even the shifting of a language is a

community efforts in meeting their interaction needs.

Natural conditions, culture, and environment are

other causes. Therefore, it is not surprising that there

is a common terminology in different languages. This

condition also occurs in the sustainability of the

cognate languages.

The languages of the Austronesian family are so

numerous, so the researchers attempted to group the

languages into smaller groups through reconstruction.

So that the Protomalay, Protobatak, and other

protolanguage are found. It is done to observe the

process of inheritance that occurs in the

protolanguage from the PAN language. PAN

language hypothetically derives the Protomalay (PM)

language and other proto language. Furthermore, the

PM language is a language that hypothetically derives

the current Malay language and its dialects, one of

them is BMA. For example, if the reconstructed is

/*p/, this protoconsonant /*p/ should be seen as a

formula characterized [+consonantal, +obstruen,

+anterior] and so on. These characteristics are made

as conclusions based on similar or almost identical

features found in /p/ in various Malay dialects. It is

impossible to describe exactly how the /*p/ sounds in

protolanguage are spoken. The phonemes derived

from the protolanguage are referred to as derived or

reflex phonemes. Thus, /p/ in a dialect is a reflex of

*p (Asmah Haji Omar, 1995). This reflex is called a

linear reflex.

A proto phoneme sometimes has only one reflex

and sometimes more than one reflexes. These

different reflexes can appear in different

environments and in different dialects. PM vowel

phonemes /*ә/, for example, have reflexes /ә/, /ɔ/, and

/a/. The relationship between one reflex and another

1178

Widayati, D., Gustianingsih, . and Lubis, R.

Conservative and Innovative Form of Proto Malay in Malay Asahan.

DOI: 10.5220/0010069111781183

In Proceedings of the International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches (ICOSTEERR 2018) - Research in Industry 4.0, pages

1178-1183

ISBN: 978-989-758-449-7

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

derived from a proto phoneme is called a diaphon

(Asmah Haji Omar, 1995). In examining this

reconstruction, it holds on the "probability factor"

which Asmah Haji Omar called the probability theory

of language change. The meaning of this theory is that

the processes of change prevailing in language

repeated from time to time. Therefore, what applies

in synchronic language change is nothing but the

repetition of the same process that prevailed in the

past (Asmah Haji Omar, 1995).

2 METHOD

There are two concepts in the inheritance system of

Protolanguage into derivative language, namely the

concepts of innovation and retention. The concept of

innovation is based on the writings of Llamzon. He

described that innovation is the continuity of change

of certain features of a language whereas if the

continuity is not changed it is called retention

(Llamzon, 1969). However, certain features can not

change up to a certain stage in its development and

therefore it can be regarded as retention from the

stage of innovation. The form of retention and

innovation in derivative languages is called a

conservative and innovative form.

The process of preserving the proto language in

the present language is called linear inheritance.

Greenberg (Fernandez, 1996) explains that in its

historical development, language can occur

independently without going through a period of

common development. This is the opposite of

innovation that the innovations experienced by

language are exclusively common through a period of

common development. Innovation is assumed to

occur when language as a whole break up into a

number of specific language subgroups [see

Widayati, 2016).

In phonology, innovation is concerned with the

rules of change that encourage the formation of new

vocabularies (Nurmaida, Sibarani, Widayati, and

Nurlela, 2019). Phonological innovations appear in

various forms of change including the number and

distribution of phonemes such as mergers and splits,

deletion, and substitutions (see also Purba, Mbete, Ni

Wayan, 2017). Regular phoneme changes in the

related languages are an earlier language heritage,

while irregular changes occur later. There are

generally two innovations: replacement and emerging

forms. Substitution is a change in the form of a parent

language cognate.

The research for conservative and innovative

forms in the BMA of the PM uses historical linguistic

analysis and comparative methods (Widayati, 2016).

Therefore, descriptive data collection is the first step

for provision of appropriate data in this study. The

natural data of the speakers strives to emerge

naturally without manipulation. Here the researchers

are required with all the ability to capture and

simultaneously analyze the data with the theories and

methods appropriate, in order to materialize the

expected research results. The data of

Protoaustronesia language (PAN) and Proto Malay

language (PM) were obtained from von Dempwolff

(1938), Nothofer (1988 dan 1975), Blust (1988),

Collins (1986), Adelaar (1994, 1988), Asmah Haji

Omar (1995), and Inyo Yos Fernandez (1996).

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The results will be discussed in two subsections, they

are the innovative and conservative forms of PM

vowels in BMA and the innovative and conservative

forms of PM consonant in the BMA

3.1 The Innovative and Conservative

Forms of PM Vowels in BMA

The PM vowel system who reconstructed by Adelaar

is similar to the Proto Austronesian vowel system,

which recognizes two high vowels /*i/ and /*u/, a

middle vowel /*ә/, and a low vowel /*a/ (Collins,

1986 ).

3.1.1 The PM High Vowels in BMA

The high vowels are distinguished over the back

vowel /*i/ and the front vowel /*u/. PM Vowel /*i/

has various reflexes in BMA, ie /i/ linearly inherited

and /a/, /e/ innovatively inherited. For example, *biar

> biaR, * kǝcik> kɔcIk, *bulih > buleh, bɔlɛh. The

PM vowel /*i/ of the open penultimate syllable

remain linearly inherent. However, in the open and

closed ultimate and penultimate syllabels /*i/ also

become [e] (on closed syllables only). This change

can be explained that in the closed syllable /i/ changes

the distinguishing feature [+ high] to [-high] and the

neutralization of the syllables before or after. The

change /* i/ > /e/ occurs because /* i / undergoes a

feature adjustment process in the presence of /ɔ/, ie [+

high] > [-high]. The process of change because of the

environment has resulted in phonemic separation /* i/

> /i/ and /e/. In the antepenultimate syllable /*i/

becomes /i/ and /a/ in BMA. The alteration of */ i/ >

Conservative and Innovative Form of Proto Malay in Malay Asahan

1179

/a/ in this syllable is the result of the second syllable

neutralization or penultimate syllable (see Adelaar,

1994). For example, *binantu> m (i, a) nantu,

*tiŋadah > t(i,a)ŋadah.

From the above description it can be concluded

that /*i/ has split into the derived phoneme, ie / i, e,

and a /. In addition, BMA also retains many archaic

forms or conservative forms that having /i/ vowel.

That is, in the BMA is still maintained PM forms. The

existence of a low vowel /e/ or /a/ is a later change

(c.f. Nothofer, 1975).

The PM vowel /*u/ has different reflexes because

of its environment. In open and closed ultimate and

penultimate syllables /*u/ > /u/. The closed syllable

[u] weakened into [U]. The distinctive features [+

height, + tense] change into [+ high, -tense]. For

example, *batu > batu, *jatuh > jatUh, *hulu >

hulu, *pǝrut > pɔRUt. However, /u/ also splits into /ɔ/

in the same environment, ie ultima and penultima

syllables. The appearance of /ɔ/ in this BMA is the

result of neutralization of low vowel sounds /e, a, or

ɔ / that located before or after neutralized sounds. For

example, *bulih> bulɛh, bɔlɛh, * iluk> ɛlɔk, *puhun>

pɔhɔn, *tuluŋ > tɔlɔŋ, and *ikuR> ikUR. That is,

BMA lexicon shows an innovative and conservative

form. In antepenultimate syllable /*u/ has a diverse

reflex: /u, i, and a/. This diversity arose sporadically

in the BMA. For example, *kuliliŋ > k(u, a)lilIŋ, *

sumaŋat > s(u, a)maŋat, *surambiʔ > s(u,a)rambi,

*subaraŋ > s(i,a)bɔRaŋ, *kulambu > k(u, a)lambu.

The emergence of an innovative phoneme, ie /a, i/ can

be called as the vowel harmony or the neutralization

of the sound of the penultimate vowel syllable.

3.1.2 The PM Middle Vowels in BMA

The PM middle vowel /*ә/ has a reflex /ɔ/, and /a/ in

BMA. These innovative reflexes appear in different

syllables. In the penultimate syllable /*ә/ is reflected

innovatively as /ɔ/. For example, *kәɲaŋ > kɔɲaŋ,

*bәlum > bɔlUm, *sәɲap > sɔɲap, *dәbu > dәbu. In

antepenultimatel/preantepenultimate and closed

ultimate syllables /*ә/ reflected as /a/. The reflex of

/a/ arises as a result of the neutralization of the vowel

in the second syllable of the end/penultimate. For

example, bәrapa > baRapɔ, *bәlakaŋ > balakaŋ,

*mәŋapa > maŋapɔ, * bәrkәlahi> bakalai. In the

closed ultimate syllable /*ә/ is inherited inovatively

as /a/. For example, *pinjәm > pinjam, *cәpәt >

cɔpat, *tahәn > tahan, *lәmәk > lɔmak, *kәbәl >

kɔbal.

3.1.3 The PM Low Vowel in BMA

The PM low vowel /*a/ on closed penultimate and

open/closed penultimate syllables are linearly

inherited in the BMA. However, in the open ultimate

syllable /*a/ > /ɔ/, whereas in antepenultimate

syllable /*a/ > /a/. That is, PM /*a/ has split in BMA.

For example, *salah > salah, *bara > baRɔ, *apa >

apɔ, *baŋkay > baŋke, *baRani > baRani, *kamuniŋ

> kamunIŋ

Reflexes of /*a/ are also present in double vowels.

There is a double vowel that appears due to the loss

of consonant /*h/ on the position between the vowels

and there is also a double vowel which is a form of

PM. For example, *bahiraʔ > bairaʔ > berak,

*sahupan > saupan > sɔpan, *baisan > besan,

*mairah > meRah. In the lexicon *bahiraʔ, at first

happening was /*h/ > /Ø/, then contraction /*ai/ > /e/

and also the lexicon *sahupan. The process is

*sahupan > *saØupan> saupan> sɔpan. On *baisan

and *mairah lexicons only the contraction process

occurs, namely *baisan > besan; *mairah> merah.

Based on the description of the PM phoneme

above and its reflexes, it can be concluded that the

BMA vowel system consists of a five-phoneme

system which is a reflex of the four PM vowel

phonemes, ie

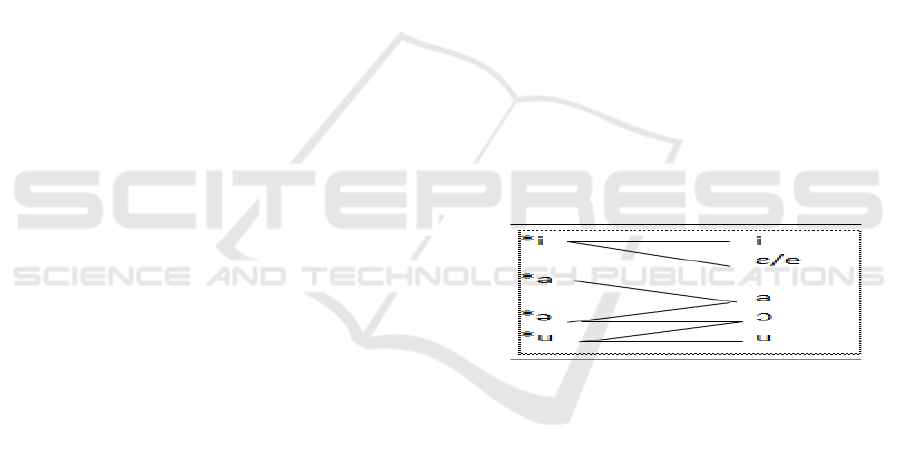

Figure 1: PM vowel reflex in BMA

3.2 The Innovative and Conservative

Forms of PM Consonants in the BMA

PAN language recognizes 25 consonants, ie, *p, *b,

*t, *d, *D, *c, *j, *k, *g, *q, *m, *n, *ɲ,* ŋ, *s, *S,

*h, *l, *r, *R, *y, *w, *z, and *Z. All consonants

occupy all positions, only consonants *T, *Z, *z, *ɲ,

and *j do not occupy the final position. The phonemic

development of the PAN consonants to PM is

described as follows (see Blust, 1988 and Fernandez,

1996 ).

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1180

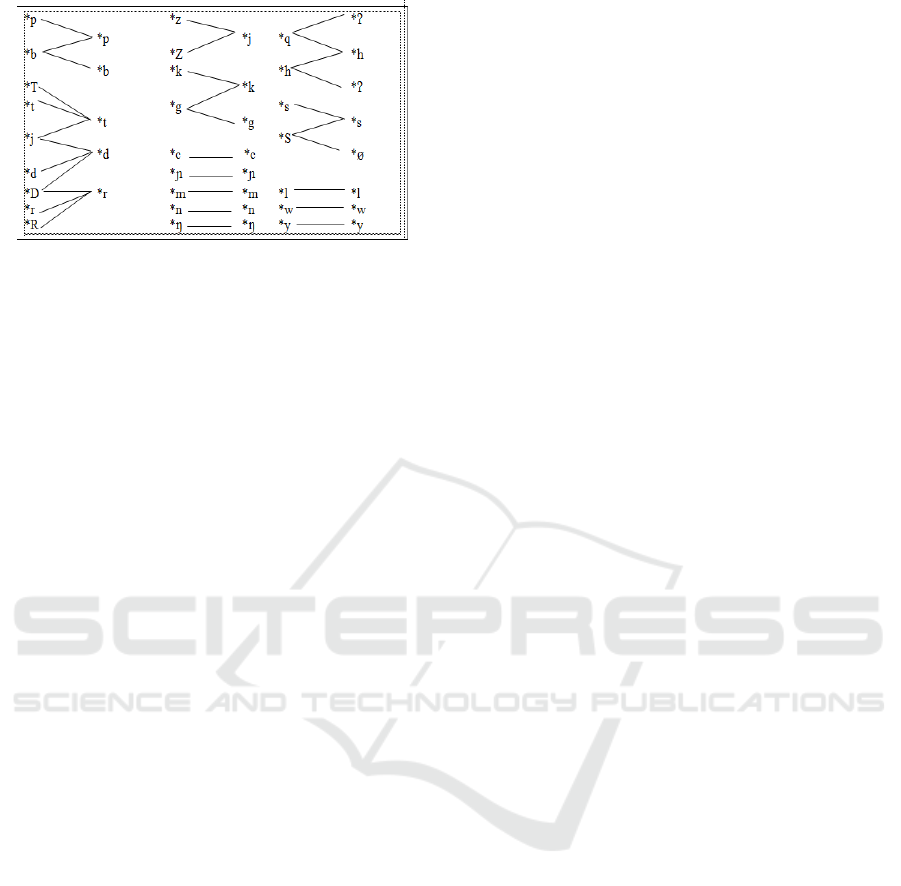

Figure 2: PAN consonants reflex in PM

3.2.1 The PM Plosive Voiceless Consonants

in BMA

Consonants of /p, t, c, k and ʔ/ typically appear in the

inter-vowel position, at the initial position, and after

the nasal consonant. The plosive voiceless PM /*c/

consonant is less common than the others. Words like

curi and cium contained in Malay are borrowing

words from a language in Northern India. According

to Zorg (Blust. 1988) the plosive voiceless

consonants in standard Malay is a derivative form that

developed later from Protopolynesia /*s or *t/, which

is reinforced by accent patterns that often appear in

the last syllables. However, according to Adelaar

(1988) this view may be true, but the developments

may have occurred before the PM stage. However, all

isolects have /c/ in at least several comparable devices

that are clearly not borrowed. That is, in

reconstructing the consonant of BMA can still be

done through PM * c.

The consonants of PM /*p and /*t/ are linearly

inherited in the BMA either in the initial, medial, or

final position without any environment. Similarly

with /*c/, but /*c/ never appears in the finial position.

For example *puluh > pulUh, *tipu > tipu, *lipәt >

lipat, *әmpat > ɔmpat, *hatәp > atap, *tuha> tu

w

ɔ,

*datәŋ > dataŋ, *bәlut> bɔlUt, *cari > caRi, *cәray

> cɔRe, *cucuk > cucuk, *bәnci > bɔnci. Those

inherited lexicons are innovative and conservative.

The deleting of /*h/ in the initial and medial positions

is a reasonable occurrence in almost every

Austronesian language. While other vowel changes

such as /*ә/ > /a/ on *hatәp > atap and /*ә/ > /ɔ/ on

*lәtup > lɔtUp are regular inheritance.

The consonant PM /*k/ is reflected as [k] and [ʔ].

The reflexes of /k/ > [k] appear in the initial and

medial positions. In the final position /*k/ PM is

innovative, ie /*k/ > [ʔ]. Actually, in this final

position /*k/ remains reflected as /k/, but this

phonetically [k] weakned to [ʔ]. The sound [ʔ] which

is the realization of /k/ is not distinctive and this is

different from the segmental phoneme [ʔ] which is

derived from /*ʔ/. For example, *kәmbar > kɔmbaR,

*kutu > kutu, *sakit > sakIt, *ikan > ikan, *tәluk >

tɔlUk.

In contrast to the consonant /*k/, the consonant

/*ʔ/ is reflected in three forms, ie /k, ʔ, and Ø/ in

BMA. The three reflexes are in the final position. The

phoneme of /*k/ and /*ʔ/ are two different phonemes.

The character is the phoneme of /*k/ in the final

position never deleted, while /*ʔ/ can be deleted in the

final position. Obviously, it appears in the following

examples, ie *baliʔ > balɛk, *datuʔ > datuk, *tapaʔ

> tapak, *bukaʔ > bukaʔ, *nasiʔ > nasiʔ, *butaʔ >

butɔ, *jәraʔ > jɔRɔ. In the final position [ʔ] appears

as a non-distinctive phoneme, as in the word *bukaʔ

> buka

ʔ. This word is used to distinguish words

*buka >bukɔ in [babukɔ puaso] and bukaʔ > bukaʔ

in [mambukaʔ pintu]. This problem also appears on

the realized muka which is realized to be [mukɔ] and

[mukaʔ]. The lexicone of [mukɔ] is used to declare

‘part of the head’, ie ‘face’ in the [lagak mukɔnyɔ]

‘pretty’, while [mukaʔ] is used to declare ‘front’ in

[pɔgi ka mukaʔ]. The appearance of reflexes /k/ and

/ʔ/ from /*ʔ/ and /*k/, indicates that there has been

partial merger and partial splits of two different proto

phonemes and and produce the same two phonemes.

In BMA’s lexicon there is *garuk, *garuʔ >

gaRut, gaRu. Both lexsemes were used in different

meanings. Lexicon gaRut is used to ‘scavenging

garbage’, while the lexicon gaRu is used to 'rub each

other from two touching/scratching itchy surfaces',

for example because it is bitten by an insect. Based on

the correspondence of sound changes from the PM

that * ʔ> Ø, it is concluded that the lexicon gaRut is

reflected from the PM *garuk, while the lexicon gaRu

is reflected from PM *garuʔ. In comparison, in

Banjar (in Borneo) and Serawai (in Palembang)

languages recognize lexicon garut/ gaxut

<*garuk/garuʔ (Adelaar, K.A. 1994).

3.2.2 The PM Plosive Voice Consonants in

BMA

The plosive voice consonants PM in BMA are /b, d,

j, and g/. All these consonants can appear in the

initial, inter-vowel, and postnasal positions (see

Adelaar, 1994). Based on this correspondence

Adelaar (1994) reconstructs that the four consonants

are reflected from /*b, *d, *j, and *g/. The consonant

PM /*b/ is present only in the initial and medial

positions. In the medial position /*b/ is present

between the vowels whether identical or not and

postnasal. In both positions /*b/ retains in derivative

languages, for example *bintaŋ > bintaŋ, and

*tumbuh > tumbUh. Only on some lexsemes that

Conservative and Innovative Form of Proto Malay in Malay Asahan

1181

correspondence cannot be explained /*b/ innovated

into /w/, for example *kaban > kawan, *taban >

tawan, *laban > lawan.

The PM consonants /*d, * j, and *g/ are present

only in the initial and medial positions. This

consonant is not found in the final position. In the

medial position /*d/ is reflected between the identical

and not identical vowels, as well as the postnasal

position. These three consonants are inherited linearly

in the BMA. For example, *dada > dadɔ, *hiduŋ >

iduŋ, *tujuh > tujuh, *injәm > pinjam, *gigi > gigi,

*tәgak > tɔgak.

3.2.3 The PM Nasal Consonant in BMA

The identifiable nasal consonants are /*m, *n, *ɲ, and

*ŋ/. The consonant of /*m/ is present in every

position, initials, medial, and final. This consonant is

reflected linearly in the BMA. In the medial position,

the consonant appears between the vowels and in

front of the homorgan plosive consonant , ie /b, p/, eg

*muncuŋ > muncUŋ, *kami > kami, *tumpul >

tumpUl, muntUl, *tajәm > tajam, *kәtәm > kɔtam.

The lexsemes surrounding the presence of /m/ in their

reflexes appear innovatively with changes in

identifiable vowels. In addition, there is also a lexsem

which is reflected conservatively.

Just like the /*m/ consonant, this /*n/ consonant

is also reflected linearly in every position. In the

medial position this consonant appears between the

vowels and in front of the homorgan plosive

consonant, ie /t, d/, eg * nibuŋ> nibUŋ, *panas >

panas, *lantay > lantɛ, *hintay > intɛ, *iŋin > iŋin,

*dәlapan >(da)lapan, *sәmbilan > sambilan. The

derived lexicons in the BMA is conservative and

innovative. This innovative lexicon arises from a

systematic change in vowels. In lexsem *dәlapan is

inherited with one syllabic deleted at the beginning of

a word. This apheresis appears sporadically.

Generally, the speakers bring it up in two syllables

only in daily speech, that is lapan. The interesting

inheritance observed is *dәlapan <* dua(ʔ)alapan

(originally meaning two taken out of ten). In addition,

there are also lexicon *sәmbilan < *әsaʔ-ambil-an

(one taken out of ten). Ambil dan alap 'take' comes

from two different etymons. In Minangkabau

language is known leksem salapan <* әsaʔ-alap-an.

Blust explains that in Minangkabau s/alap/an ‘eight’

comes from the lexicon of origin s/alap/an

synonymous with s/embil/an 'nine' (Blust, 1988).

This lexicon then undergoes a change of meaning to

'eight' because of the loss of the original

morphological function of this form, ie sa <* әsa. In

leksem of

*binantu > minantu there is a substitution

of the plosive consonant in the third syllable of the

end (antepenultimate syllabel) with nasal homorgan,

ie b > m.

The consonant /*ɲ/ exists only in the initial and

medial positions between the vowels and in front of

the homorgan plosive consonant /c, j/. For example,

*ɲamuk > ɲamUk, *aɲam > aɲam, *kәɲaŋ > kɔɲaŋ,

*taɲaʔ > taɲɔ. Lexicons of *muncuŋ > muncuŋ

actually phonetically appear sounds of [ɲ] in front of

[c], ie [muɲcuŋ]. The realization of /n/ dental to [ɲ]

palatal occurs due to a regressive assimilation process

of palatal sound [c]. There has been a feature change

of /n/ in the cluster of [nc] from [+ dental, + nasal] >

[ɲ] in the cluster of [ɲc] [+ palatal, + nasal]. The

similar processes to this change is for example

*cincin > [ciɲcin], *[bәnci] > [bɔɲci], *kanciŋ >

[kaɲcIŋ]. Similarly with /n/ in the cluster /nj/ is the

feature change from [+ dental, + nasal] become [-

dental, + nasal], i.e. [ɲj]. For example *tunjuk >

[tuɲjUk], *janji > [jaɲji]. The consonant of /*ŋ/ is

also reflected linearly in all positions in the BMA. In

the medial position, the consonant /*ŋ/ is present

between the vowels and in front of of the homorgan

plosive consonant, ie /k, g/, eg. *ŋәri > ŋɔRi, *sәŋәt>

sɔŋat, *baŋkay > baŋke, *taŋgaʔ > taŋgɔ.

3.2.4 The PM Liquid (lateral, trill)

Consonants in BMA

The PM liquid consonants are /*r and *l/ which are

reflected innovatively in BMA. The consonants of

/*r/ innovate in all positions to velar fricative /R/, for

example, *rusaʔ > Rusɔ, *buruŋ > buRuŋ, *hilir >

hiliR. The reflexes of /*r/ to be velar fricative

hypothesized as the result of separation from Proto

Malay Polynesian (PMP) fricative /*R/ and trill /*r/

into /*r/ (PM) and become /R/ (BMA). For example,

*DaRaq > *darah > daRah, *DәŋәR > *dәŋәr >

dɔŋaR, *Rumaq > *rumah > Rumah, *ular> * ular

> ulaR. The PM consonant of /*l/ is reflected linearly

in all positions. For example, *lamaʔ > lamɔ, *malu

> malu, *gatәl > gatal.

3.2.5 The PM Fricative Consonant PM in

the BMA

The PM fricative consonants are /*s and *h/. Fricative

/*s/ reflected linearly at the initial, medial positions

between the vowels and the postnasal, and the final

position in the BMA. For example, *saraŋ > saRaŋ,

*bisik > bisik, *suŋsaŋ > suŋsaŋ, *haus > aus, *ruas

> Ruas. Conservative lexicons appear in BMA. Also,

the consonant of /*h/ PM is reflected linearly in the

medial position between the vowels and the final

ICOSTEERR 2018 - International Conference of Science, Technology, Engineering, Environmental and Ramification Researches

1182

position. In the initial position /*h/ innovated to be

/Ø/. For example, *harimaw> aRimɔ, * huban>

uban, *halia> aliɔ, * tihaŋ> tiaŋ, *tuha > tua, *tahan

> tahan, *pilih > pilih. This apheresis /*h/ appears

regularly, but in the lexicon that having an additional

[+ emotion], /h/ more often appear than not. Its

function is to give emphasis to the spoken lexicon.

For example hapak> hapak 'smell moist', harum >

hɔRum 'fragrance'. In the medial position between

identical vowels /h/ still exist, but /h / deletes

between vowels that are not identical. That is, /*h/ has

a split in BMA, ie /h/ and / Ø /.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The vowels are generally reflected in an innovative

rather than consonant. nnovative reflexes on the

vowels cause the reflected lexicons to be innovated.

The high vowel /*i/ is reflected into /i/ and /e/.

Meanwhile the vowel /*u/ is split into /u/ and /ɔ/. The

middle vowel /*ә/ is reflected into /a /and /ɔ/

innovatively. The vowels /*a/ and /*ә/ simultaneously

merge into /a/. Innovatively reflected consonants are

found in /*h/, /*k/, /*ʔ/, and /*r/ consonants. The

plosive voiceless consonants /*p/, /*t/, and /*k/ are

reflected at all positions linearly. Meanwhile, the /*c/

consonant appears only in the initial and medial

positions, and /*ʔ/ only appears in the final position.

The plosive voiced consonants i.e /*b/, /*d/, /*j/, and

/*g/ are only reflected in the initial and medial

positions linearly. The nasal consonants /*m/, /*n/,

and /*ŋ/ are also reflected in all positions linearly, but

/*ɲ/ is reflected only in initial and medial positions.

The liquid consonant /*r/ and /*l/ and fricative /*s/

and /*h/ are reflected in all positions. /*r/ consonant

is innovated into /R/, while /h/ is split into /h/ and /Ø/.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was financially supported by

Universitas Sumatera Utara in according to

TALENTA Universitas Sumatera Utara Research

Contract for the Year 2018 Number 2590/

UN5.1.R/PPM/2017 dated March 16

th

, 2018.

REFERENCES

Adelaar, K.A, 1988. ”More on Proto-Malayic”. Dalam

Rekonstruksi dan Cabang-Cabang Bahasa Melayu

Induk. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. Kuala Lumpur.

Adelaar, K.A, 1994. Bahasa Melayik Purba: Rekonstruksi

Fonologi dan Sebagian dari Leksikon dan Morfologi.

RUL. Jakarta

Asmah Haji Omar, 1995. Rekonstruksi Fonologi Bahasa

Melayu Induk. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. Kuala

Lumpur

Blust. Robert A, 1988a. Austronesian Root Theory: An

Essay on The Limits of Morphology. John Benjamins.

Amsterdam/Philadelphia.

Blust. Robert A, 1988b. “Malay Historical Linguistics: A

Progress Report”. Dalam Rekonstruksi dan Cabang-

Cabang Bahasa Melayu Induk. Dewan Bahasa dan

Pustaka. Kuala Lumpur

Bynon, Theodora, 1979. Historical Linguistics. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press Collins, James.T. 1986.

Antologi Kajian Dialek Melayu. Dewan Bahasa dan

Pustaka. Kuala Lumpur.

Fernandez, Inyo Yos, 1996. Relasi Historis Kekerabatan

Bahasa Flores. Nusa Indah. Flores.

Llamzon, Teodoro A, 1969. A Subgrouping of Nine

Philippine Languages. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Nothofer, Bernd, 1975. The Reconstructions of Proto

Malayo-Javanic. Martinus Nijhoff. ‘S-Gravenhage

Nothofer, Bernd, 1988. “A Discussion of Two Austronesia

Subgroups: Proto-Malay and Proto-Malayic”. In

Rekonstruksi dan Cabang-Cabang Bahasa Melayu

Induk. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. Kuala Lumpur.

Nurmaida, Robert Sibarani, Dwi Widayati, Nurlela, 2019.

International Journal of Humanities and Social

Science; 5 (9): 268-272. ISSN 2220-8488 (Print),

2221-0989 (Online) www.ijhssnet.com

Purba, Maria Apulina, Aron Meko Mbete, Ni Wayan

Arnati, 2017. Jurnal Humanis, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya

Unud; 21(1): 129-134

Von Dempwolff, Otto. 1938. Austronesisches

Worterverzeichnis. Friederichsen, Der Gruyter.

Hamburg.

Widayati, Dwi, 2016. “Vocal and Consonant PAN Features

in Nias and Sigulai Languages”. Dalam “International

Journal of Linguistics, Language and Culture (IJLLC);

online at http://ijcu.us/online/journal/index.php/ijllc-si

; Vol. 2, No. 4, November 2016, pages: 74~82 ; ISSN:

2455-8028

Conservative and Innovative Form of Proto Malay in Malay Asahan

1183