Regulating Online Speech in Malaysia

Playing the Devil’s Advocate on the Fake News Law Dichotomy

Mazlina Mohamad Mangsor, Mazlifah Mansoor, Noraiza Abdul Rahman

Faculty of Law, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

Keywords: Communications, Fake News, Freedom of Speech, Multimedia Law, Online Content.

Abstract: On 2 April 2018, the Malaysian House of Representative passed the Anti-Fake News Act 2018 (‘AFNA

2018’). The former Law Minister emphasised that the objective of the legislation is to protect the public from

the proliferation of fake news. On the contrary, advocates of human rights criticise that the new law is

extremely vague and disrespectful of the right to freedom of speech. Thus, the fake news legislation creates a

dichotomy between maintaining public order and nurturing the fundamental rights of the citizen in a

democratic society. This paper argues that regulating online speech in Malaysia under the AFNA 2018 scheme

still raises concerns with regard to the infringement of the right to freedom of speech and requires the urgent

attention from the relevant authorities. This paper aims to critically examine the normative aspects of the

AFNA 2018 and other relevant legislation addressing false content. This paper commences with a

constitutional review of the AFNA 2018. It continues to discuss other existing laws. This paper concludes

that AFNA 2018 contains a number of flaws that does not promote ones’ constitutional right to freedom of

speech. This paper employs a qualitative and doctrinal research method through content analysis approach.

1 INTRODUCTION

Malaysian political landscape has transformed since

the introduction of the Anti-Fake News Act 2018

(hereinafter ‘the AFNA 2018’). Since Malaysia’s

independence in 1957, the old regime has been in

power for 61 years by one political coalition, the

National Front (‘Barisan Nasional’ or hereinafter ‘the

BN’). The BN is said to maintain its hegemony

through authoritarian actions including incumbent-

favoured gerrymandering and media dominance

(Ueda, 2018). It is under this former reign the AFNA

2018 was enacted. The new government historic

victory during the 14th general election promises

better Malaysia and Malaysian with the hope of

upholding the rights of the people, particularly the

freedom of speech and expression. It is no surprise

that this promise leads to a proposed legislative

measure to repeal the AFNA 2018 (Bernama, 2018).

Prior to the enforcement of the AFNA 2018, few

existing laws have been applied to regulate issues

related to online and offline fake content. Although

some may argue about the lacking aspects of the latter

legislation, the instrumental considerations in the

ineffectiveness of the current laws to control false

content has not been empirically highlighted. The

passing of the AFNA 2018 marked a more stringent

approach on fake contents. Ironically, the

enforcement of the AFNA 2018 has taken placed a

month before the 14th Malaysian general election on

9 May 2018. Critics proposed that the primary aim of

the AFNA 2018 is to silence any criticism of the

ruling government and the related issues including the

1MDB crisis (Hutt, 2018). In addition, human rights

activists have raised concern on the breach of the right

to freedom of speech and expression under the fake

law regime (Hutt, 2018; Human Rights Watch, 2018;

Sipalan, Menon & Birsel, 2018).

The objective of the study is to critically analyse

the normative aspects of the AFNA 2018 and current

laws in relation to false content. This paper explains

the constitutional position of the freedom of speech

and expression in Malaysia. This paper also examines

the statutory limitations of the right in light of the

AFNA 2018, the Communications and Multimedia

Act 1998, the Printing Presses and Publications Act

1984 and the Penal Code. This paper concludes that

AFNA 2018 contains a number of flaws that does not

promote ones’ constitutional right to freedom of

speech.

Mangsor, M., Mansoor, M. and Rahman, N.

Regulating Online Speech in Malaysia Playing the Devil’s Advocate on the Fake News Law Dichotomy.

DOI: 10.5220/0010053501630170

In Proceedings of the International Law Conference (iN-LAC 2018) - Law, Technology and the Imperative of Change in the 21st Century, pages 163-170

ISBN: 978-989-758-482-4

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

163

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

This paper employs a qualitative and doctrinal

research method through content analysis approach

where the normative facets of the AFNA 2018 and

other legislation are examined. It comprises of

primary and secondary sources through the library-

based research. Whilst the first encompasses of

Malaysian legislation, policies and judicial decisions,

the latter constitutes a significant proportion of online

databases content including LexisNexis, Westlaw and

others.

The existing laws prior to the introduction the

AFNA 2018 are briefly discussed with emphasis on

the applicability of the laws to control fake content.

The authors acknowledge that the Defamation Act

1957 also impliedly addresses the issue of fake news

but due to the constraint, the Defamation Act 1957

will not be discussed in this paper.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Freedom of Speech and Expression

The international recognition of the right to freedom

of speech and expression is manifested in the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (hereinafter

‘the UDHR’). Malaysia is a signatory to the first

global expression of human rights, on a limited scale.

This is reflected in light of Section 4(4) of the Human

Rights Commission of Malaysia Act 1999 that regard

shall be had to the UDHR to the extent that it is not

inconsistent with the Malaysian Federal Constitution.

Article 19 of the UDHR lays down the following

provision:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and

expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions

without interference and to seek, receive and impart

information and ideas through any media and regardless

of frontiers;

The phrase ‘freedom to hold opinions without

interference’ does not connote an absolute right to

freedom of speech and expression at the international

level. This is due to the conditions stated under

Article 29 of the UDHR in order to impose any

limitations on the right to free speech. Article 29 of

the UDHR highlights the following aspects:

…everyone shall be subject only to such

limitations as are determined by law solely for the

purpose of securing due recognition & respect for

the rights & freedoms of others & of meeting the

just requirements of morality, public order & the

general welfare in a democratic society..

Any restraints must fulfil a three-part test,

approved by the United Nation Human Rights

Committee (Human Rights Committee, 2011). The

conditions of the test are first, the restriction must be

provided by law, which is clear and accessible to

everyone. This requirement highlights the principle of

legal certainty, predictability and transparency in

order to prevent arbitrariness by the relevant

authority. Second, the limitation must fulfil one of the

purposes set out in Article 19(3) of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (hereinafter

‘the ICCPR’). The ICCPR (1966) underlines the

premise to protect the rights, reputations of others, to

protect national security, public order or public health

or moral and the principle of legitimacy. Third, the

restraint must be proven necessary and restrictive

means which are needed. The restraint must also

correspond with the purpose in light of the principle

of necessity and proportionality. The term ‘necessary’

must demonstrate a pressing social need and protect

legitimate interests (Human Rights Committee,

2011).

The Malaysian position of the right to freedom of

speech and expression is enshrined in Article 10(1) of

the Federal Constitution as follow:

subject to clauses (2),(3) & (4) every citizen has

the right to freedom of speech and expression

Similar to the international approach, the freedom

is not absolute and the limitations are provided under

Articles 10(2)(a) and 10(4) of the Federal

Constitution. Articles 149 and 150 of the Federal

Constitution also authorise restriction on free speech

on the grounds of subversion and emergency

situations. However, the above mentioned Malaysian

limitations under the Federal Constitution are slightly

differed from the international measures in terms of

the requirements and principles that have been

emphasised. The requisite standard of ‘necessity’

aiming to safeguard a legitimate public interest with

a pressing social need are not clearly embedded in the

drafting of the legal mechanism to restrict free speech

in Malaysia. Some of the laws are politically driven

to address the current situations including the

introduction of the AFNA 2018.

Whilst Article 10(2) (a) of the Federal

Constitution allows the Parliament to pass law on

eight grounds to restrict free speech, Article 10(4) of

the Federal Constitution restricts the act of

questioning four highly sensitive issues in Malaysia.

In addition, Articles 149 and 150 of the Federal

Constitution provided two more grounds to restraint

free speech. The grounds are provided in the

following table:

iN-LAC 2018 - International Law Conference 2018

164

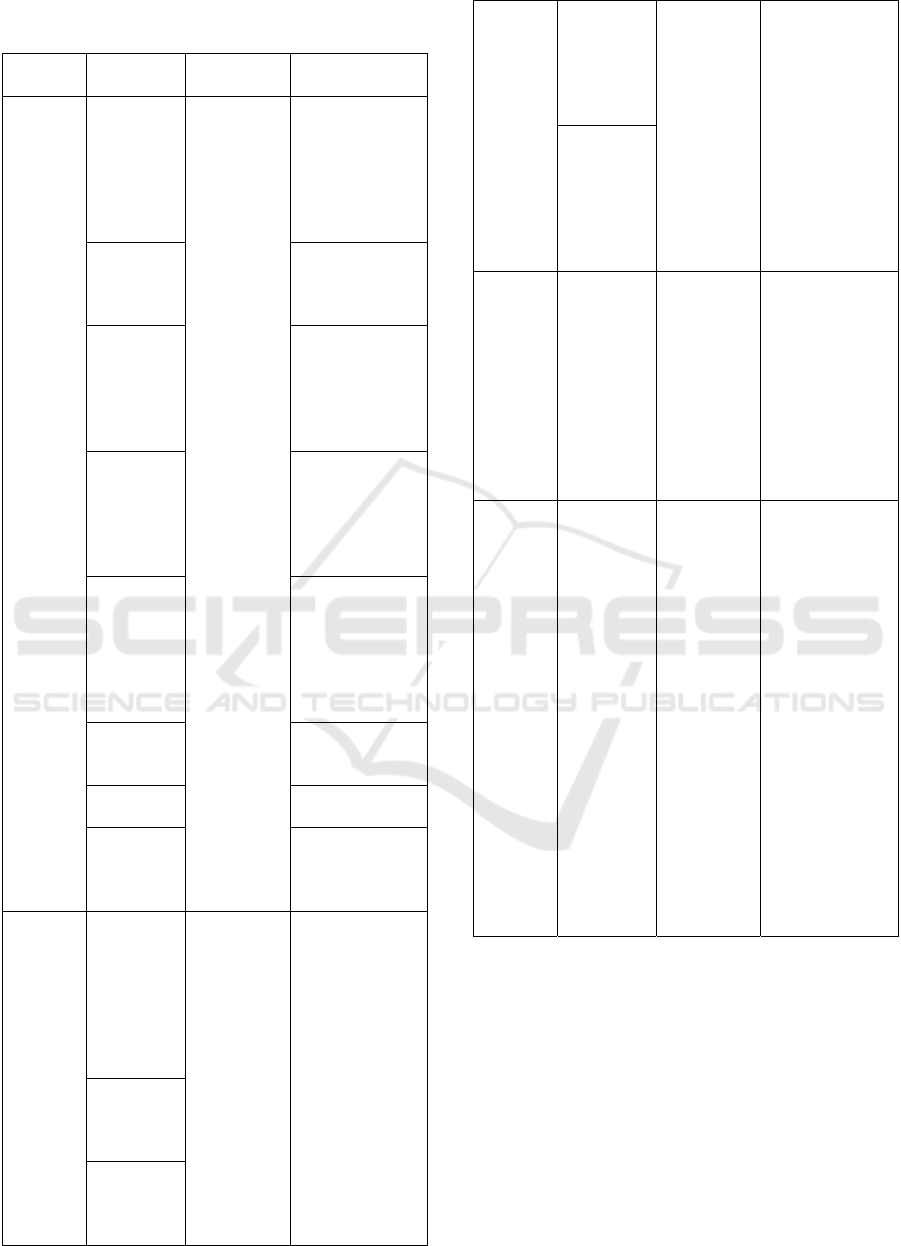

Table 1: Constitutional grounds to restrict free speech in

Malaysia.

Article Grounds Restriction

s

Law Enacted

Art

10(2)(a)

Security Allows any

legislative

measure to

restrict the

freedom of

speech

under any

of the eight

grounds

Security

Offences

(Special

Measures) Act

2012 & Official

Secret Act

1972

Friendly

relation

with other

countries

Public

order

Sedition Act

1948, Police

Act 1967 &

Printing Presses

& Publications

Act 1984

Morality Film

Censorship Act

2002 &

Printing Presses

& Publications

Act 1984

Protection

of the

privileges

of

Parliamen

t/ SLA

House of

Parliament

(Privileges &

Powers) Act

1952 & the

Standing

Orders

Contempt

of Court

Courts of

Judicature Act

1964

Defamatio

n

Defamation Act

1957

Incitement

to any

offence

Obscenity

under sections

292-294 of

Penal Code

Art

10(4)

Rights to

citizenshi

p

(Part III of

the

Federal

Constituti

on)

Allows any

legislative

effort to

restraint

the

questionin

g of the

four

matters

Adopted under

section 3(1)(f)

of the Sedition

Act 1948

Status of

the Malay

language

(Art 152)

Position

and

privileges

of the

Malays

and native

of Sabah

and

Sarawak

(Art 153)

Sovereign

ty and

prerogativ

e of the

Malay

Rulers

(Art 181)

Art 149

Subversio

n,

organised

violence

& crime

prejudicial

to public

order

Permits

any

legislative

action that

infringe

the

freedom of

speech

under

Article

10(1)

Security

Offences

(Special

Measures) Act

2012 &

Sedition Act

1948

Art 150

Allows

any laws

required

by reason

of an

emergenc

y

Permits

any

legislative

measure

that

changes

the

provision

of the

Federal

Constitutio

n except

for six

grounds,

by which

freedom of

speech is

not

included

Article

150(6A)

Emergency

(Essential

powers)

Ordinance No.

1, Emergency

(Essential

powers)

Ordinance No.

2

&

Emergency

(Security

Cases)

Regulations

1975. These

ordinances and

regulation have

been repealed

in 2011.

The above table illustrates the extensive power of

the Malaysian Parliament granted by the Federal

Constitution to enact laws restraining the right to

freedom of speech and expression under fourteen

grounds.

3.2 The Anti-fake News Act 2018

The AFNA 2018 consists of four parts and fourteen

sections. This law has an extra-territorial application

under Section 3 of the AFNA 2018. It is also

applicable to Malaysian and foreigner outside

Regulating Online Speech in Malaysia Playing the Devil’s Advocate on the Fake News Law Dichotomy

165

Malaysia provided that the fake news concerns

Malaysia or any Malaysian. Section 2 of the AFNA

2018 defines ‘fake news’ to include the following:

Any news, information, data, and reports, which

is or are wholly or partly false, whether in the

form of features, visuals, or audio recordings or

in any form capable of suggesting words or ideas.

The abovementioned definition claimed to be so

general and judicial interpretations are needed to

determine the meaning of fake news whereby under

the former regime demonstrated a heavy disposition

towards the ruling party (Hutt, 2018). The broad

meaning of ‘fake news’ covers public and private

communications; actual reporting and online

gossiping; and media inaccurate information and an

individual lying text message (Lim, 2018; Hutt,

2018). Furthermore, the term ‘fake news’ also creates

a twist, ‘a content that is fake cannot be news’ (Lim,

2018). The blurring aspect of the meaning of ‘fake

news’ can easily be used to infringe the peoples’ right

to freedom of speech and expression. In other

jurisdiction, academics and non-governmental

organisations took initiatives to define fake news and

to discuss the viability of workable solutions (Baron

& Crootof, 2017).

The AFNA 2018 creates six new offences. First,

knowingly and maliciously creates, offers, publishes,

prints, distributes, circulates or disseminates fake

news or publication of fake news. Second, the act of

providing financial assistance for purpose

committing or facilitating offences under Section 4;

and intends or knows or have reasonable grounds to

believe financial assistance will be used for fake

news. Third, failure to carry out duty to remove fake

news content after knowing or having reasonable

grounds to believe it is fake news. While the fourth

offence is about a failure to comply court order for

removal of publication containing fake news, the fifth

offence is abetment or assisting in any of the above

offence. Sixth, the AFNA 2018 criminalises the act

done by a corporation and any officer of the

corporation may deem to be severally or jointly liable

for the same offence.

The offences are illustrated in further details in the

following table:

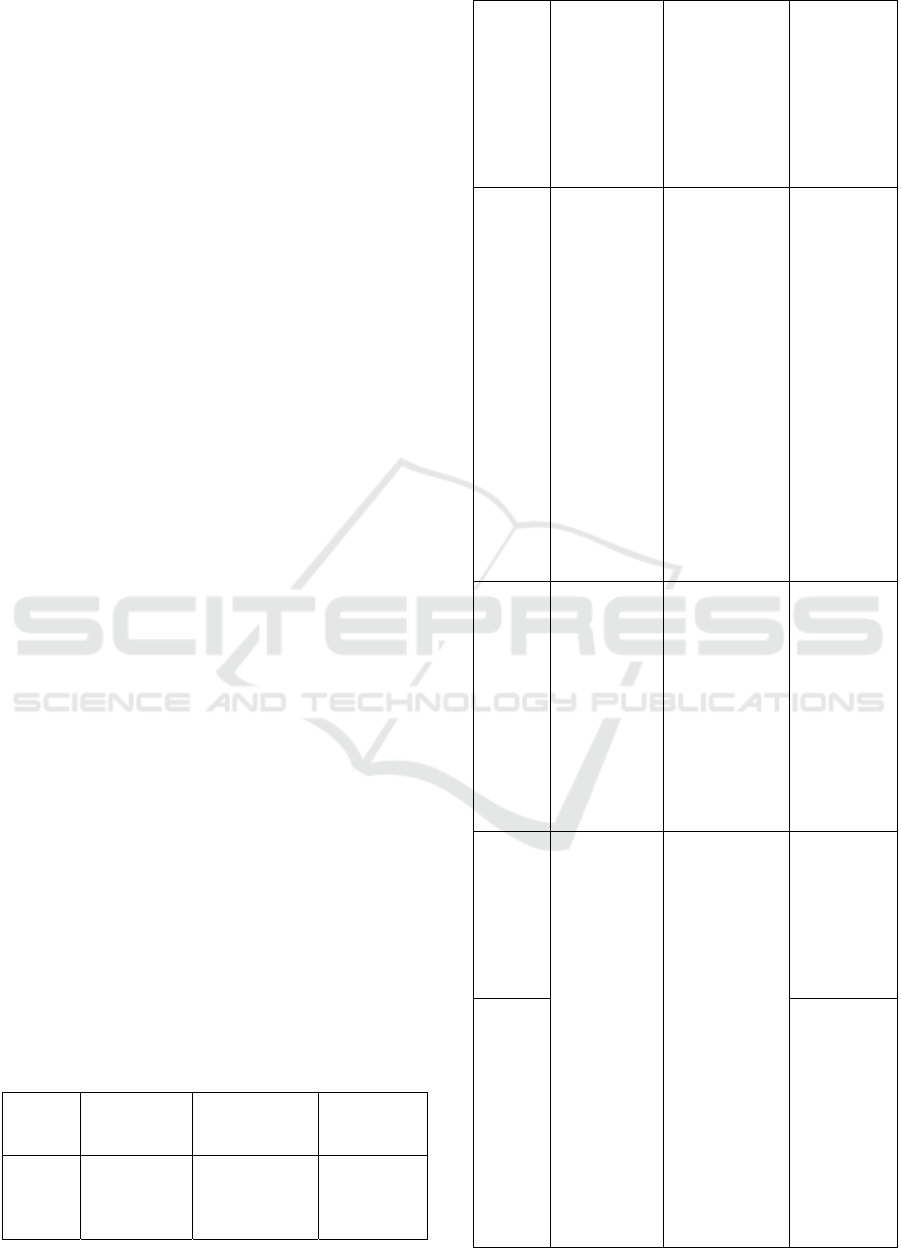

Table 2: Offences under the AFNA 2018.

Sectio

n

Offence Penalty Additional

Order/

Condition

S 4 Maliciously

creates,

offers,

publishes,

Maximum

RM500,000

fine/

Failure to

make an

apology as

ordered by

prints,

distributes,

circulates/

disseminate

s fake news/

publication

of fake

news

maximum 10-

year jail/ both

Maximu

m daily

RM3000 fine

if offence

continues

after

conviction

Court shall

be

punishable

as a

contempt of

court

S 5 Provides

financial

assistance

for purpose

committing

/ facilitating

offences

under

section 4 /

intends/

knows/ have

reasonable

grounds to

believe

financial

assistance

will be used

for fake

news

Maximum

RM500,000

fine/

maximum 10-

year jail/ both

S 6 Failure to

carry out

duty to

remove fake

news

content after

knowing/

having

reasonable

grounds to

believe it is

fake news

Maximum

RM100,000

fine

Maximu

m daily

RM3000 fine

if offence

continues

after

conviction

S7 Failure to

comply

court order

for removal

of

publication

containing

fake news

Maximum

RM100,000

fine

Court order

can be

served by

post or by

electronic

means

including

emails

S8 May apply

to set aside

of order for

removal of

publication

containing

fake news

provided

not under

the grounds

of

prejudicial

iN-LAC 2018 - International Law Conference 2018

166

to public

order/

national

security

S9 Non-

compliance

, court may

order police

officer to

remove

publication

s of fake

news

S10 Abetment

(assisting)

in any of the

above

offence

Punishment

provided for

the offence

S13 Offence by

body

corporate

Punishment

provided for

the offence

Any officer

of the

corporation

may deem

to be

severally or

jointly

liable

unless

proven that

he or she

has no

knowledge/

not

consented/

taken

reasonable

precautions

The abovementioned offences highlight few

significant implications to individuals and

corporations. Section 4 of the AFNA 2018

criminalises a range of online activities from creating,

uploading, blogging, posting, reposting, forwarding,

retweeting and sharing a link of the fake news in the

social media and other platforms. Thus, a click or a

tap of retweeting the fake news may cause an

individual to be imprisoned 10 years or lesser or to be

fined RM500,000.00 or lesser or both. Section 4 of

the AFNA 2018 also provides few scenarios to

illustrate the online activities including the scenario

such as ‘A publishes an advertisement about a person

Z as a successful investor, when Z was never involved

in such activity. A is guilty’. Critics argued that the

ubiquitous nature of the Internet and the advancement

of the technology make it difficult to control the

dissemination of the online fake news (Shanmugam,

2018). It will be more challenging if it is disseminated

by a foreigner in a foreign country.

Section 6 of the AFNA 2018 states that once a

person realised that he or she communicates the fake

news, there is a duty to remove or to delete the news.

This creates a burden to the individuals and may also

apply to the administrators of social media platforms

including Google, Twitter and Whatsapp (Lim,

2018).

3.3 The Communications and

Multimedia Act 1998

The Communications and Multimedia Act 1998

(hereinafter ‘the CMA 1998’) governs the online

content. Two essential sections addressing false or

fake contents are Sections 211 and 233 of the CMA

1998. Section 211 of the CMA 1998 prohibits the use

of content applications service by a person to provide

any content that is deemed to be false and with intent

to annoy or abuse another person. Section 233 of the

CMA 1998 disallows the use of network facilities or

network services by a person to transmit any

communication that is deemed to be false and with

intent to annoy or abuse another person. Both sections

impose a maximum fine of RM50,000 or a maximum

one-year jail term or both, and a further fine of

RM1,000 for every day the offence is continued after

conviction.

On 13th April 2018, two individuals were fined

RM3,000 each for fake postings on social media over

the seizure of seventy-four containers containing

beef, lamb and pork in the previous year (Nazlina,

2018). Both were charged under Section 233(1) (a) of

the CMA 1998. In 2017, forty individuals had been

investigated by the Malaysian Communications and

Multimedia Commission (hereinafter ‘the MCMC’)

and four were charged for spreading and sharing false

news (Jaafar, Wan Alias & Shamsuddin, 2018). The

former Minister of Communications and Multimedia

Datuk Seri Salleh Said Keruak highlighted the

creation of many fake social media accounts on

Facebook and Twitter which intended to spread false

content that ‘might adversely impact the country’s

social and economic well-being, as well as national

security’ (Jun, 2017). In 2017, 2,000 fake accounts

were investigated by the MCMC and 1,500 fake

accounts were put into action including blocking and

closing the accounts (Jun, 2017).

Section 233 of the CMA 1998 invokes a chilling

effect on the freedom of speech and expression

(Thiru, 2015). Under this Section, any person who

disagrees with any statement made online by any

other person to the extent that it arouses a feeling of

hurt and disgust in him, could immediately use this

Section as a tool not only to silence out the other

Regulating Online Speech in Malaysia Playing the Devil’s Advocate on the Fake News Law Dichotomy

167

person whose opinion he finds disagreeable and also

to use to the might of the State in punishing him for

something which any reasonable person is entitled to

express under freedom of speech. Thiru (2015)

echoed that the continuous application of the said

section to restraint views, discourse and expression,

and to limit democratic space, ‘creates a climate of

fear that threatens to silence Malaysians’.

Malaysian media landscape witnesses a group of

victims charged under this Section ranging from a

radio journalist, the Malaysian Insider editor, a

whistleblower of Sarawak Report, a political analyst

to a former Chief Minister (Thiru, 2015). This

development evidenced the effectiveness of the said

section to control false content to the extent that it

received a heavy criticism on the implementation of

the law (Thiru, 2015).

3.4 The Printing Presses and

Publications Act 1984

The Printing Presses and Publication Act 1984

(hereinafter ‘the PPPA 1984’) defines the phrase

‘newspaper’ and ‘publication’ to include a wide range

of documents including reports, visible

representations and anything capable of suggesting

words or ideas. Section 8A (1) of the PPPA 1984

creates an offence for maliciously published false

news. All the parties involved including the printer,

publisher, editor and the writer shall be subjected to

imprisonment not exceeding three years or to a fine

not exceeding twenty thousand ringgit or to both. The

news is malicious if the accused failed to prove that

he took reasonable measures to verify the truth of the

news under section 8A (2) of the PPPA 1984.

Section 8A of the PPPA 1984 has been applied in

a number of cases receiving media attention. Irene

Fernandez, a renowned journalist, who wrote about

the alleged abuse of illegal immigrants, was

convicted under this section (Faruqi, 2008). Irene was

imprisoned for 12 months after she appeared in court

310 times. ARTICLE 19 & SUARAM (2005)

claimed that this case was the longest running trial in

the legal history of Malaysia.

In the case of Lim Guan Eng v PP [1988] 3 MLJ

14, the accused, a Member of Parliament, published

pamphlets containing the phrase ‘victim imprisoned,

criminal free’. The phrase ‘victim imprisoned’ was

held to be false and malicious. The victim, 16 years

old was gang raped and later was ordered to undergo

rehabilitation at a centre. In addition, she also alleged

been sexually violated by a former chief minister. The

charge against the politician was dropped due to lack

of evidence.

The constitutionality of Section 8A was tested in

the case of PP v Pung Chen Choon (1994) 1 MLJ 566.

The reasoning behind the review was rejected on the

said section invoking a blanket restriction on false

news without connecting the restraint to the grounds

permitted under Article 10 (2) of the Federal

Constitution (Faruqi, 2008).

3.5 Penal Code

The Penal Code (hereinafter ‘the PC’) criminalises an

act of disseminating of false reports. Section 124I of

the PC provides that it is an offence to orally spread

false reports or to make the false statements in writing

in any newspaper, periodical, book, circular, or other

printed publication or electronic means and likely to

cause public alarm. An individual can be imprisoned

for five years. The provision highlights that false

reports can be disseminated using either traditional

printed documents or electronic media including

social media platforms, in which the AFNA 2018 has

a similar parameter.

The offence does not count the act of creating the

false reports as in the AFNA 2018. However, if the

false report is disseminated, the crime is committed.

Furthermore, this provision clearly constructs the

implication of the action ie ‘likely to cause public

alarm’. In order words, if a false report does not cause

public alarm, the individual may rebut the charge

against him or her.

3.6 Comparative Analysis

The above discussions on controlling fake news

encapsulates few significant closures in the following

table.

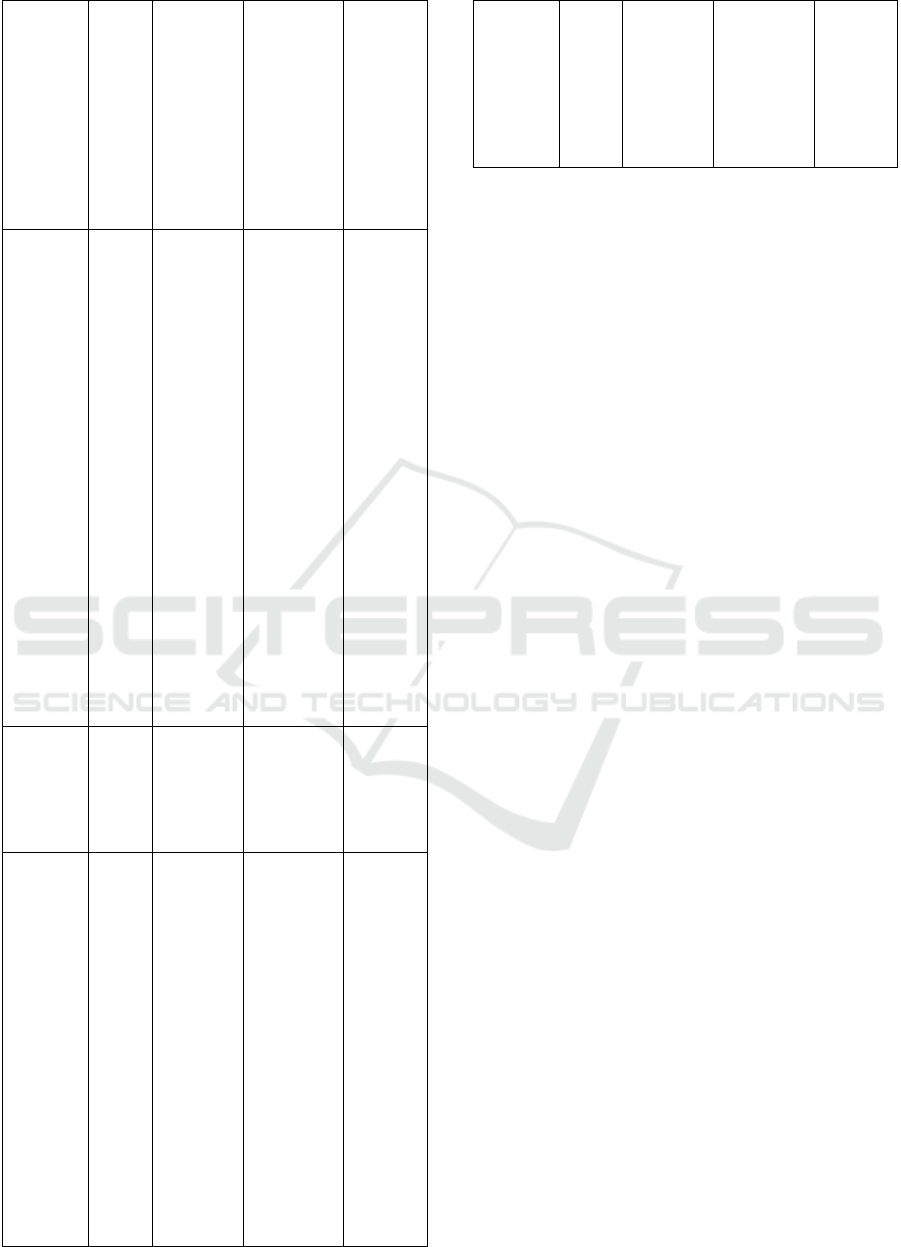

Table 3: Selective types of offences and punishments.

Legislat

ion

Secti

on

Offence Punishme

nt

Additio

nal

Order

The

AFNA

2018

S4 Maliciou

sly

creates,

offers,

publishes

, prints,

distribute

s,

circulates

/

dissemin

ates fake

news/

Maximum

RM500,00

0 fine/

maximum

10-year

jail/ both

Maximu

m daily

RM300

0 fine if

offence

continu

es after

convicti

on

Failure

to make

an

iN-LAC 2018 - International Law Conference 2018

168

publicati

on of

fake

news

apology

as

ordered

by

Court

shall be

punisha

ble as a

contem

pt of

court

The

CMA

1998

S233 Knowing

ly makes,

creates,

solicits

and

initiates

the

transmiss

ion of

false

content

by means

of

network

facilities

or

network

services

with

intent to

annoy or

abuse

another

person

Maximum

RM50,000

/ one year

imprisonm

ent/ both

Maximu

m daily

RM100

0 fine if

offence

continu

es after

convicti

on

The

PPPA

1984

S8A Maliciou

sly

publishe

d false

news

Maximum

RM20,000

/ three

years

imprisonm

ent/ both

The

Penal

Code

S124

I

Orally

spread

false

reports

or to

make the

false

statement

s in

writing

in any

newspap

er,

periodica

l, book,

circular,

or other

printed

publicati

Maximum

5 years

imprisonm

ent

on or

electroni

c means

and

likely to

cause

public

alarm

The existing law ie the CMA 1998, the PPPA

1984 and the PC reflected the applicability of the

legislation to address the online fake news with a

lesser degree of punishment. The said legislation also

provide a clear implication of the criminal mind or

mens rea in order to punish an individual in particular,

the Penal Code with ‘likely to cause public alarm’ and

the CMA 1998 with ‘an intent to annoy or abuse

another person’. The CMA 1998 is broad enough to

play the devil’s advocate on the fake news law

dichotomy. Furthermore, the broad and vague nature

of the AFNA 2018 may breach the right to the

freedom of speech by placing a burden to individuals

and social media administrators to remove the fake

news once known to them.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In short, the introduction of the AFNA 2018 provides

specific platform or sui generis to address the

proliferation of the false news. However, the

existence of other relevant laws creating an

overlapping jurisdiction and multiple approaches

dealing with a similar online content raises concern.

In addition, a number of flaws identified under the

AFNA 2018 requires urgent action from the relevant

authorities including the vagueness of the AFNA

2018.

REFERENCES

ARTICLE 19, 2016. Annual Report 2016: Defending the

right to speak and the right to know.

<https://www.article19.org/data/files/medialibrary/387

34/Annual_report-FINAL.pdf>

ARTICLE 19 & SUARAM, 2005. Freedom of Expression

and the Media in Malaysia. <https://www.

article19.org/data/files/pdfs/publications/malaysia-

baseline-study.pdf>

Baron, S. & Crootof, R., 2017. Fighting Fake News: The

Information Society Project & The Floyd Abrams

Institute for Freedom of Expression.

<https://law.yale.edu/system/files/area/center/isp/docu

ments/fighting_fake_news_-_workshop_report.pdf >

Regulating Online Speech in Malaysia Playing the Devil’s Advocate on the Fake News Law Dichotomy

169

Bernama, 2018. Gobind: Anti-Fake News Act will be

abolished <https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/

2018/05/22/gobind-antifake-news-act-will-be-

abolished/>

Faruqi, S.S., 2008. Reflecting on the law: Freedom on the

march. The Star, 14 May 2008.

<https://www.thestar.com.my/opinion/columnists/refle

cting-on-the-law/2008/05/14/freedom-on-the-march/>

Human Right Committee, 2011. General Comments No 34:

Article 19: Freedom of speech and expression. United

Nations.<https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybo

dyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2fC%2

fGC%2f34&Lang=en>

Human Rights Watch, 2018. Malaysia: Drop proposed

‘fake news’ law. Human Right Watch, 29 March 2018.

<https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/03/29/malaysia-

drop-proposed-fake-news-law>

Hutt, D., 2018. The real problem with Malaysia’s fake news

law. The Diplomat, 5 April 2018.

<https://thediplomat.com/2018/04/the-real-problem-

with-malaysias-fake-news-law/>

ICCPR, 1966. International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights. United Nations Human Rights, Office of the

High Commissioner, 16 December 1966.

<https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/

ccpr.aspx>

Jaafar, N., Wan Alias, W. N. H. & Shamsuddin, M. A.,

2018. MCMC can catch fake news spreaders in 24

hours. The New Straits Times, 8 March 2018.

<https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2018/03/34311

6/mcmc-can-catch-fake-news-spreaders-24-hours>

Johnson, G. R., 2002. The First Founding Father: Aristotle

on Freedom and Popular Government. Liberty and

Democracy. Hoover Press. (page 29-30)

<http://media.hoover.org/sites/default/files/documents/

0817929223_29.pdf>

Jun, S. W., 2017. 227 cases of misuse of new media,

including social media, probed last year. The New

Straits Times, 15 August 2017

<https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2017/08/26819

9/227-cases-misuse-new-media-including-social-

media-probed-last-year>

Lim Guan Eng v PP [1988] 3 MLJ 14

Lim, I., 2018. Watch out! ‘Fake news’ law covers

Facebook, WhatsApp admins, private messages. The

Malay Mail, 27 March 2018.

<https://www.malaymail.com/s/1607895/watch-out-

fake-news-law-covers-facebook-whatsapp-admins-

private-messages>

Shanmugam, M., 2018. Why bothers on the laws on fake

news?. The Star, 10 March, 2018.

<https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-

news/2018/03/10/why-bother-with-laws-on-fake-

news/>

Nazlina, M., 2018. Two charged for fake news… but under

CMA, not new fake news law. The Star, 13 April 2018.

<https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/04/13

/two-charged-for-fake-news-but-under-cma-not-new-

fake-news-law/#p2bYMmRvKseMKrrx.99 >

PP v Pung Chen Choon (1994) 1 MLJ 566

Sipalan, J., Menon, P. & Birsel, R., 2018. Malaysia outlaws

‘fake news’; sets jail of up to six years. Reuters, 2 April

2018. <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-malaysia-

election-fakenews/malaysia-outlaws-fake-news-sets-

jail-of-up-to-six-years-idUSKCN1H90Y9>

Thiru, S., 2015. Section 233(1)(a) of the Communications

and Multimedia Act 1998 Creates a Chilling Effect on

Freedom of Speech and Expression, and Should be

Repealed. The Malaysian Bar.

<http://www.malaysianbar.org.my/press_statements/pr

ess_release_%7C_section_2331a_of_the_communicat

ions_and_multimedia_act_1998_creates_a_chilling_ef

fect_on_freedom_of_speech_and_expression_and_sho

uld_be_repealed.html>

Ueda, M., 2018. Malaysia’s New Political Tsunami. The

Diplomat, 12 May 2018.

<https://thediplomat.com/2018/05/malaysias-new-

political-tsunami/>

iN-LAC 2018 - International Law Conference 2018

170