State Obligation to Combat Enforced Disappearance: An Empirical

Analysis in Bangladesh Perspective

Syed Robayet Ferdous

School of Law, University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Keywords: Bangladesh, Enforced Disappearance, Enforced Disappearance Convention, National Law.

Abstract: Enforced disappearance has been committed by members of the ruling political party, with the alliance of law

enforcement agencies to intimidate political opponents in Bangladesh. Besides, law enforcement agencies

gain pecuniary benefits from enforced disappeared victims and families, precipitating impunity as an agent of

the ruling political party. Therefore, it is essential to stop this practice, not only for ensuring the human rights

but also to protect the image of law enforcement agencies in Bangladesh. Purpose of this scholarship is to

provide a summary of state liabilities to combat enforced disappearance under the domestic laws of the land.

To know the level of compliance with the Enforced Disappearance Convention (from now on the Convention)

is the other purpose of this manuscript. The quantitative methodology has been used to know the level of

compliance with the provisions of Enforced Disappearance Convention, and the result shows that Bangladesh

complies to a minimum level with the provisions of the Convention. Also, this paper reveals that enforced

disappearance may be reduced if Bangladesh ratifies the Convention. The qualitative result demonstrates that

even though, Bangladesh has not ratified the Convention; however, it must combat enforced disappearance

under the Constitutional law as well as the Criminal law of the Land.

1 INTRODUCTION

The enforced disappearance was first manifested on

December 7, 1941, when Adolf Hitler issued “Nacht

und NebelErlass” as known as the Night and Fog

Decree (Dalia Vitkauskaitė-Meurice, Justinas

Žilinskas, 2010, p. 197). In the late 1960s, in Brazil

and then in Guatemala where enforced disappearance

re-emerged under Latin American military ruler by

the name of so-called national security (Dalia

Vitkauskaitė-Meurice, Justinas Žilinskas, 2010, p.

198). In between the 1970 and 1980, enforced

disappearance was a common phenomenon in many

States of this region. In addition to Latin America, the

extreme level of enforced disappearances was

reported and occurred in Iraq, Sri Lanka and the

former Yugoslavia (Nowak, M. 2009, p. 152). In

Bangladesh, the enforced disappearance was first

reported in 1971 during the Liberation War.

Numerous distinguished intellectuals and scholars

were abducted, and their locations remained

unidentified until their bodies were found (Odhikar,

2016, p. 14).

The international community firstly addressed

enforced disappearance as a breach of human rights

and created a framework agenda to combat enforced

disappearance. Thereafter, adopted three specific

international instruments known as the UN

Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from

Enforced Disappearances, (GA Res. 47/133, 1992);

Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance

of Persons, (OAS Doc. OEA/Ser.P/Doc.3114/94,

1994); and finally the UN International Convention

for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced

Disappearance, (UN Doc. A/61/488, 2006) and this

Convention is the expansion of the Rome Statute of

the International Criminal Court, 1998. According to

these three instruments enforced disappearance is

amount to be crimes against humanity under the

specific circumstances (Irena Giorgou, 2013). Now,

enforced disappearance is not only a violation of

human rights but also an international crime.

The Convention came into force on December 23,

2010, intended to prevent enforced disappearance. As

of June22, 2018, 58 states had ratified, and 97

countries have signed the Convention (United

Nations Treaty Collection, n.d.). Bangladesh has not

yet ratified the Convention as well as reluctant to

follow the Conventional provision and presumes that

Ferdous, S.

State Obligation to Combat Enforced Disappearance: An Empirical Analysis in Bangladesh Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0010049400790086

In Proceedings of the International Law Conference (iN-LAC 2018) - Law, Technology and the Imperative of Change in the 21st Century, pages 79-86

ISBN: 978-989-758-482-4

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

79

she is free from any obligation adopted by this

Convention.

Though Bangladesh has not ratified the Convention,

she is responsible in many aspects to follow the

Conventional provisions under the national law of the

land. To address the above statements, the research

questions have been set in the following:

Does Bangladesh oblige to combat enforced

disappearance under the national law of the

land? If so,

To what extent are the provisions of

Convention implemented to combat

enforced disappearance in Bangladesh?

These research questions explored the people’s

perception regarding compliance with the provisions

of Convention as well as the people's rights

guaranteed by laws of the land. The study also

assesses, evaluates, and analyzes the State obligations

to follow the Convention as well as national laws of

the land to combat enforced disappearance.

2 RESEARCH DESIGN

The method of the study is qualitative as well as

quantitative in nature. Both primary and secondary

information have been collected according to the

following table.

Table 1: The following table shows how to respond to the research questions:

Research Questions Method(s) Tools Sample Respondents

Compliance with the

provisions of Convention to

combat enforced

disappearance in Bangladesh

Quantitative

Structured& Semi-

structured Questionnaire

Yes

Law Students of public

& private universities in

Dhaka, Bangladesh.

FGD

KII Law Faculties of public

& private universities in

Dhaka, Bangladesh

The obligations to combat

enforced disappearance under

the national law of the land.

Qualitative

Primary sources Secondary sources

National statutes, i.e.,

Constitution, Penal

Code/leading cases/judicial

opinions and so on.

Articles/ books/book-chapters in the

edited volume/blogs and so on.

In the quantitative method, a total of 213 data has

been collected between February and March 2018,

using convenient sampling technique. FGD and KII

were developed to capture some necessary qualitative

information about students’ and teachers’ perceptions

which were not covered by the structured

questionnaire. The questionnaire included various

statements, and perceptions of the students were

measured by the response of interviewees to the

separate items at a 5-Point Likert Scale. Point-5

indicates strongly agree; on the contrary point-1

means strongly disagree with a statement.

1

Odhikar is one of the leading human rights non-

governmental organizations in Bangladesh. Odhikar is a

Bangla (native)word that means ‘rights'. On October 10,

1994, it came into being with the aiming

3 COMPLIANCE WITH THE

PROVISIONS OF

CONVENTION

In recent times, the incident of enforced

disappearance is unusually rising in Bangladesh.

According to Odhikar,

1

enforced disappearance is a

new form of violation of human rights in Bangladesh

which was recognized since 2009(Odhikar, 2017, p.

6). In 2017, a record number of extra-judicial killing

in the form of crossfire and enforced disappearance

perpetrated by government law enforcement agencies

(Odhikar, 2017, p. 7). The UN Human Rights

Committee, in its concluding observation of the

ICCPR on March 28, 2017, termed the Bangladesh

government as critical on such issues. The Committee

at creating a broader monitoring and awareness raising

system on the abuses of civil and political rights.

iN-LAC 2018 - International Law Conference 2018

80

also expressed concern about the high level of

enforced disappearances and the extreme use of force

by the State security forces (United Nations Human

Rights Committee, 2017). Though Bangladesh has

not ratified this Convention, however, she is

responsible for combating enforced disappearance in

many aspects under the national law of the land. To

address the State’s obligation, a survey was

conducted between February and March 2018, in

Dhaka, Bangladesh to fulfill one of the objectives of

this study. At first, the respondents were asked by the

following three yes/no/undecided general questions,

intended to know their perceptions about the

ratification and compliance with the Convention.

Question_1: Bangladesh should ratify and

practice Enforced Disappearance Convention.

Question_2: Enforced disappearance will be

reduced if Bangladesh ratifies the Convention.

Question_3: Bangladesh has customary

obligation to comply with the Convention.

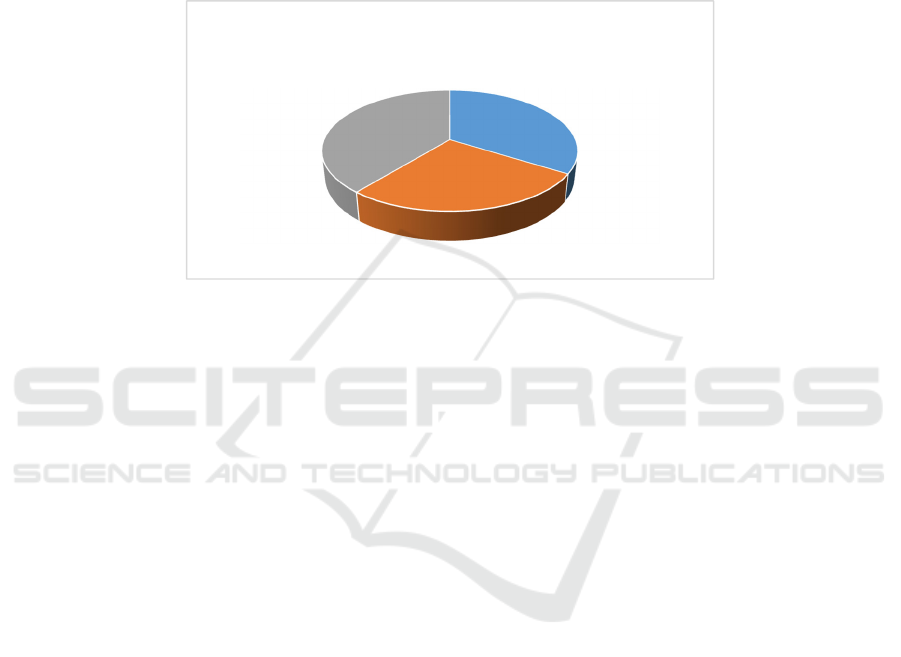

Figure 1: shows that Bangladesh should ratify and comply with the Convention, ratification of the Convention will reduce on

enforced disappearance, and Bangladesh has customary obligation to comply with the Convention.

According to figure 1, about 91% of the respondents

opined that Bangladesh has customary obligation to

comply with the Convention. About 79% of the

respondents think that Bangladesh should ratify and

implement the provisions of Convention. Also, about

63% of the respondents agree that enforced

disappearance will be reduced if Bangladesh ratifies

the Convention.

Comparatively less number of the respondents

think that enforced disappearance will be reduced if

Bangladesh ratifies the Convention. However, this

number of percentage is high (63%). Therefore, it can

be said that the ratification of the Convention is

positively associated to reduce the enforced

disappearance. As a result, a hypothesis can be

developed in the following manner:

H1: ratification of the Convention can reduce

enforced disappearance.

The Focus Group Discussion (FGD) and Key

Informant Interview (KII) argues that Bangladesh has

ratified numerous international Covenants and

Conventions adopted by the UN. For example, the

Rome Statute of ICC, International Covenant on Civil

and Political Rights (ICCPR), Torture and Other

Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or

Punishment (CAT), Geneva Conventions, Additional

Protocols, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

(UDHR). All the instruments mentioned above

expressly or impliedly suggest combatting enforced

disappearance. Therefore, the State is responsible for

combatting enforced disappearance under these

instruments. As a result, it is better to sign and ratify

the Convention and gain acceptance from the

international community. The KII exposes that after

ratification if Bangladesh fails to reduce the enforced

disappearance or if the disappearance trend raises, the

state will have to account and face severe criticism;

thus, the state is unwilling to ratify the Convention.

The survey data replied to the questions of a fair

investigation, appropriate penalties, abductors

brought to justice, and to combat enforced

disappearance in figure 2.

1_Question,

79%

2_Question,

63%

3_Question,

91%

%Yes

State Obligation to Combat Enforced Disappearance: An Empirical Analysis in Bangladesh Perspective

81

Figure 2: shows a limited level of compliance with the provisions of a fair investigation, penalty, abductor brought to justice,

and to combat enforced disappearance.

The Convention has been adopted to combat

enforced disappearance. Under article 1 (2) of the

Convention in any circumstances such as internal

political instability or public emergency or any state

of war or threat of war may not invoke as a defense

for forced disappearance. However, according to

figure 2, only about 49% of the respondents agree that

there is no enforced disappearance in Bangladesh,

and only 20% of the respondents think that

Bangladesh follows the provisions of Convention to

combat enforced disappearance.

Article 3 of the Convention states that the state

party shall be responsible for prosecuting the

perpetrators. Also, according to article 4 of the

Convention, state party shall criminalize forced

disappearance under its national criminal law.

Nonetheless, figure 2 shows only 43% of the

respondents who think that the perpetrators are

brought to justice, and only 31% of the respondents

opined that the perpetrators get appropriate penalty

under the national criminal law.

The State is also responsible for providing

stringent punishment to the perpetrators who take into

account the extreme seriousness of the offence as per

the provision of article 7 of the Convection.

Furthermore, according to article 12 of the

Convention, the victim has a right to report to the

appropriate authority, and article 3 refers that the state

will be responsible for investigating the allegation

promptly and fairly. Nevertheless, according to figure

2, only 40%of the respondents think that the State

complies with these provisions.

The survey data replied to the questions of secret

detention, official registers, access to information,

access to the progress report, and adequate

compensation as shown in figure 3.

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

Peoplearenotenforceddisappearedin

Bangladesh

Theabductorisbroughtandresponsibleto

justice

Stateprovidesappropriatepenaltiesagainst

theperpetrator

Enforceddisappearanceinvestigationisfair

ineachstage

BangladeshfollowtheConventiontocombat

forceddisappearance.

49%

43%

31%

40%

20%

Agree

iN-LAC 2018 - International Law Conference 2018

82

Figure 3: shows a limited level of compliance with the Convention particularly on compensation, investigation and progress,

access to information, to maintain official registrar, and secret detention.

Article 24 of the Convention states that the victim

of forced disappearance has a right to get fair

compensation. However, according to figure 3, only

19% of the respondents agree that the victim of the

enforced disappearance has been accorded adequate

compensation.

The government is responsible for maintaining an

official register of enforced disappearance, and the

State must ensure that no one may beheld in secret

detention following article 17 of the Convention.

However, only39% of the respondents believe that

the Government maintains official registers about the

enforced disappearance incidents, and only 47% of

the respondents think that no one is held in secret

detention in Bangladesh.

Further, the State must provide information to

victim’s relatives following article 18 of the

Convention. Also, the Government is obliged to

provide all progress and investigation report to the

victim's relatives in accordance with article 24 of the

Convention. The data indicates that only 30% of the

respondents opined that the relative of the victims

have access to get information from the Government

while only 37% of the respondents think that relatives

of the victims of enforced disappearance have access

2

For example: Armenia (Art. 392, Criminal Code);

Belgium (136ter, Criminal Code); Australia (Section

268.21, International Criminal Court (Consequential

Amendments) Act 2002); Canada (Sections 4(1) (b), 6(1)

(b), Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act);

Colombia (Arts 165, 166, Criminal Code); Bosnia and

Herzegovina (Art. 172(1) (i), Criminal Code); Costa Rica

(Art. 379, Criminal Code); Croatia (Art. 1, Decision No. 01-

081-03-3537/2); El Salvador (Arts 364–366, Criminal

Code); Ethiopia (Art. 281, Criminal Code); Guatemala (Art.

to get the investigation and other progress reports

from the Government.

So, to answer the first research question, the

discussion can be summarized that the provisions of

Enforced Disappearance Convention have not been

adequately implemented in the context of

Bangladesh.

4 THE OBLIGATION UNDER

THE DOMESTIC LAWS

The Enforced Disappearance Convention obliges the

State to criminalize forced disappearance under their

national laws (Sourav, 2015). The Convention

emphasizes to enact a national law to take necessary

steps against enforced disappearance (Enforced

Disappearance Convention, 2006, art. 4) and the

Convention intends to encourage the national law to

take additional steps to combat enforced

disappearance (Enforced Disappearance Convention,

2006, art. 8.3). In response to the above provisions,

different countries enacting their national laws to

combat enforced disappearance.

2

However, there isno

201ter, Criminal Code); Cyprus (Law No. 23 (III)/2006);

Ireland (Sections 7(1), 9(1), International Criminal Court

Act 2006); Paraguay (Art. 236, Criminal Code); Mali (Art.

29(1), Criminal Code); South Africa (Sections 1(vii), 4(1)

and Schedule 1, Implementation of the International

Criminal Court Act 2002); Republic of the Congo (Art. 6(i),

(k), Law No. 8-98); Trinidad and Tobago (Section 10(2)(i),

International Criminal Court Act 2006); Malta (Section 2,

International Criminal Court Act 2002); Venezuela (Art.

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50%

Nooneheldinsecretdetention

Govt.maintainofficialregistersof…

Relativescanaccessinformation…

Relativesgetallprogress,…

Victimsgetadequatecompensation

47%

39%

30%

37%

19%

Agree

State Obligation to Combat Enforced Disappearance: An Empirical Analysis in Bangladesh Perspective

83

explicit provision in the Penal Code of Bangladesh,

1860 against enforced disappearance. However, the

provisions relating to abduction under section 362

3

and kidnapping under section 359 (classify two types

of kidnapping: kidnapping from Bangladesh

4

and

kidnapping from lawful guardianship

5

) in the Penal

Code, 1860 may amount to be similar to the meaning

of enforced disappearance (Huq, 2010). Therefore,

the perpetrators shall be held liable for breach of the

said provisions.

6

However, there is no successful

prosecution record against the perpetrators in the

experience of Bangladesh.

Along with the criminal responsibilities, the State

has Constitutional

7

obligation to combat enforced

disappearance. According to Ratner, Abrams &

Bischoff, (2009, pp. 128-129) enforced

disappearance is a cumulative violation of human

rights; thus, it may affect many aspects. For example,

victims are deprived of right to dignity (Constitution

of Bangladesh, 1972, art. 11); right to protection of

the law (Constitution of Bangladesh, 1972, art. 31);

right to be free from arbitrary detention and right to

human conditions during detention (Constitution of

Bangladesh, 1972, art. 33); right to fair trial

(Constitution of Bangladesh, 1972, art. 35); right to

life (Constitution of Bangladesh, 1972, art. 32); right

not to be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman

or degrading treatment or punishment (Constitution

of Bangladesh, 1972, art. 33); and right to free

movement (Constitution of Bangladesh, 1972, art.

36). All the rights mentioned above has guaranteed by

the Constitution of Bangladesh and enforceable by a

competent court of the State (Islam, 2010). In (Edriss

El Hassy v. The Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, 2007) the

United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC)

focused on the duties of the State party and mentioned

the responsibilities of the State parties to establish

proper judicial as well as administrative mechanisms

for combating the alleged abuses under the national

law. In its General Comment No. 31, the UNHRC

181-A, Criminal Code); United Kingdom (Sections 50, 51,

58, International Criminal Court Act 2001).

3

“Whoever by force compels, or by any deceitful means

induces, any person to go from any place, is said to abduct

that person."

4

“Whoever conveys any person beyond the limits of

Bangladesh without the consent of that person, or of some

person legally authorized to consent on behalf of that

person, is said to kidnap that person from Bangladesh

according to section 360 of Penal Code, 1860.”

5

According to section 361 of the Penal Code, 1860,

“whoever takes or entices any minor under fourteen years

of age if a male, or under sixteen years of age if a female,

or any person of unsound mind, out of the keeping of the

addressed that if a State party fails to investigate the

allegations of violation, it may amount to be a breach

of the Convention. The committee also recalled that

every State party is duty-bound to eliminate enforced

disappearance (Sourav, 2015, pp. 233-234).

From the discussion mentioned above, can be

summarized that Bangladesh has a clear obligation to

combat enforced disappearance under the national

criminal law as well as Constitutional law as the

supreme law of the land. However, the shattering

truth is that none of the perpetrators was brought to

justice for committing the offence of enforced

disappearance. No law has been implemented to

protect the rights of disappeared victims. Instead,

there has been a sequence of arbitrary arrest, kidnap,

abduction, extra-judicial killings and excessive use of

power by the Government law enforcement officials

as well as internal political armed groups which has

resulted into the breach of the rights of innocent

individuals.

5 CONCLUSION WITH

RECOMMENDATIONS

Bangladesh has a clear obligation to combat enforced

disappearance under the numerous provisions of its

national laws. However, the State has failed to

combat enforced disappearance under the law of the

land(Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust

(BLAST) and others, 2003).Also, the existing

criminal law is insufficient to protect from

indiscriminate arrest and enforced disappearance

(“Enforced disappearances must be halted,” 2010).

The codified domestic laws have some limitation to

criminalize the perpetrators under a uniform category

of offence such as crime against humanity. In the

absence of the application of UN Conventional

provisions, the Government actively precludes media

coverage of death in custody, does not grant anybody

lawful guardian of such minor or person of unsound mind,

without the consent of such guardian, is said to kidnap such

minor or person from lawful guardianship.”

6

“Whoever kidnaps any person from Bangladesh or from

lawful guardianship, shall be punished with imprisonment

of either description for a term which may extend to seven

years, and shall also be liable to fine” and “Whoever

kidnaps or abducts any person in order that such person may

be murdered or may be so disposed of as to be put in danger

of being murdered, shall be punished with imprisonment for

life or rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend

to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine” according to

existing Penal Code in Bangladesh.

7

The Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

iN-LAC 2018 - International Law Conference 2018

84

to visit any spot of extra-judicial killings (“Enforced

disappearances must be halted,” 2010).

In the experience of Bangladesh, most of the

enforced disappearances committed by the

Government law enforcement agencies such as

police, Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) and so on. A

tradition has been set up that the ruling political party

uses law enforcement agencies to commit enforced

disappearance to intimidate the political opponents.

The law enforcement agencies sometimes, gain

pecuniary benefits from the enforced disappeared

victims and relatives, precipitating impunity as an

agent of the ruling political party. The recent seven

murder heinous incident committed by the RAB high

ranking officials in Narayanganj in 2014is a glaring

example (Sourav, 2015, p. 221).

Therefore, true political wisdom among the

political parties is essential to combat enforced

disappearance in Bangladesh. The Government may

establish a new department under the domestic court

of justice to deal with the enforced disappearance

incidents. A healthy and independent judicial

committee may investigate each incident with due

care and prudence. Along with this initiatives, a

comprehensive training can make it clear to the law

enforcement agencies that the enforced disappearance

is equivalent to war crime and crime against humanity

(Alexander Murray, 2013, p. 59; US v Greifelt et

at,1948; US v Altstoetter et al. 1947)for which an

individual and the State may have to face prosecution

under the International Criminal Court.

Bangladesh ratified the Convention against

Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading

Treatment or Punishment 1984 (CAT). Therefore it is

a conventional obligation under article 10 of CAT to

train and educate the law enforcement agencies about

the prohibition of torture during arrest and detention.

To prevent torture, Bangladesh must periodically

review arrest, detention, and interrogation as

provided under article 11of the CAT.

The civil society actors can play an active role to

combat enforced disappearance. The civil society can

suggest the Government to ratify and comply with the

Convention as well as enact a domestic law to prevent

enforced disappearance. They can participate in the

debate on new legislation to battle against the

enforced disappearance. The international

community can play an important role to stop

enforced disappearance in Bangladesh. In their

diplomatic relations, they can refer to forced

disappearance as a crime against humanity. Donor

agencies may urge the Government to ensure that, no

one will be kidnapped or tortured or enforced to

disappear for their different political identity and

everyone will get equal protection of the law

regardless of the political identity. The international

community also may urge the Government to ratify

the Convention and its compliance incorporating new

provisions in domestic criminal law in parity with the

Convention.

Bangladesh is an active member of the United

Nations and a robust participant in several UN

peacekeeping missions. To keep the goodwill intact,

the State should take necessary steps to ratify the

Convention, amend the national criminal law with a

view to refraining her from the onslaughts of enforced

disappearances.

6 LIMITATION

Enforced disappearance violate disappeared

relatives’ rights (Alexander Murray, 2013, p. 57;

Maria del Carmen Almeida de Quinteros et at v

Uruguay, 1990). However, this paper does not

include this issue. Therefore, disappeared relatives

rights may be the future scope of the study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to thank Professor Ilario M. I. Maiolo,

Department of Law, University of Ottawa for his

valuable guidelines for writing this manuscript. I am

thankful to Emdadul Haque, Assistant Professor,

Department of Law & Justice, Southeast University,

Dhaka for proofreading of this paper.

REFERENCES

Alexander Murray, 2013. Enforced Disappearance and

Relatives' Rights before the Inter-American and

European Human Rights Courts, 2 Int'l Hum. Rts. L.

Rev. 57.

Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST) and

others, 55 (2003) DLR (HCD) 363.

Dalia Vitkauskaitė-Meurice, and

JustinasŽilinskas,2010.The Concept of Enforced

Disappearances in International Law.

Jurisprudencija/Jurisprudence, 2(120).

Edriss El Hassy v. The Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, 2007. U.N.

Doc. CCPR/C/91/D/1422/2005. Communication No.

1422/2005. Retrieved from

http://www.worldcourts.com/hrc/eng/decisions/2007.1

0.24_El_Hassy_v_Libya.htm.

Enforced disappearances must be halted. (2010, August

24). Asian Legal Resource Centre. Retrieved from:

www.scoop.co.nz/stories/ WO1008/S00381/enforced-

State Obligation to Combat Enforced Disappearance: An Empirical Analysis in Bangladesh Perspective

85

disappearances-must-be-halted.htm. Date of accessed:

February 28, 2018.

Huq, 2010. Penal Code, 5th ed. (Publisher:

AnupamGyanBhander).

Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of

Persons, (1994, June 9) OAS Doc.

OEA/Ser.P/Doc.3114/94.

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons

from Enforced Disappearance, (2006, December 20).

UN Doc. A/61/488.

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons

from Enforced Disappearance, Art. 4 (2006, December

20). UN Doc. A/61/488.

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons

from Enforced Disappearance, Art. 8.3 (2006,

December 20). UN Doc. A/61/488.

Irena Giorgou, 2013. State Involvement in the Perpetration

of Enforced Disappearance and the Rome Statute,

Journal of International Criminal Justice, Volume 11,

Issue 5, Pages 1001–1021,

https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqt063.

Islam, 2010. Constitutional Law of Bangladesh, 2nd ed.

(Publisher: Mullick Brothers).

Maria del Carmen Almeida de Quinteros et at v Uruguay,

(1990). Communication No. 107/1981, UN Doc.

CCPR/C/OP/2 at 138.

Nowak, M. 2009. Torture and enforced disappearance. In

International Protection of Human Rights: A Textbook.

Krause, C.; Scheinin, M. (eds.). Turku: Institute for

Human Rights, Abo Akademi University.

Odhikar, 2017. Annual Human Rights Report of

Bangladesh. Available online at http://odhikar.org/wp-

content/uploads/2018/01/Annual-HR-Report-

2017_English.pdf. Date of accessed: June 17, 2018.

Odhikar,2016. Annual Human Rights Report of

Bangladesh. Available online at http://odhikar.org/wp-

content/uploads/2017/01/AHRR-2016_Eng.pdf. Date

of accessed: February 17, 2018.

Ratner, Abrams & Bischoff, 2009. Accountability for

Human Rights Atrocities in International Law: Beyond

the Nuremberg Legacy, 3rd ed. (Publication: OUP).

Sourav, Md. Raisul Islam, 2015. Defining the Crime of

Enforced Disappearance in Conformity with

International Criminal Law: a New Frontier for

Bangladesh. Bergen Journal of Criminal Law and

Criminal Justice. 3(2):221-235 DOI

10.15845/bjclcj.v3i2.909.

The Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh,

1972.Articles, 11,31, 32, 33, 35, 36 ofThe Constitution

of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Retrieved from

http://bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd/pdf_part.php?id=367.

UN Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from

Enforced Disappearances, (1992, December 18). GA

Res. 47/133, 1992. Retrieved from

http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/47/a47r133.htm.

United Nations Treaty Collection. (n. d.). Retrieved from

https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IN

D&mtdsg_no=IV-16&chapter=4&clang=_en. Date of

accessed: June 17, 2018.

United Nations Human Rights Committee, 2017.

Concluding observations of the ICCPR on the initial

report of Bangladesh (Adopted by the Committee at its

119th session on 6-29 March). Retrieved from

http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/

Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2fC%2fBGD%2f

CO%2f1&Lan g=en. Date of accessed: June 22, 2018

US v Greifelt et at., 1948. 'The RuSHA Case', Trials of War

Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals, vol.

V (United States Government Printing Office:

Washington)

US v Altstoetter et al., 1947. 'The Justice Case', Trials of

War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military

Tribunals, vol. III, (United States Government Printing

Office: Washington).

iN-LAC 2018 - International Law Conference 2018

86