Syllable Awareness of Indonesian Children with Developmental

Dyslexia

Yanti Br Sitepu, Harwintha Yuhria Anjarningsih and Myrna Laksman-Huntley

Linguistics Department, Faculty of Humanities, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia

yantisitepu@live.de

Keywords: Syllable Awareness, Phonological Representation, Dyslexia.

Abstract: Goswami (2010) revealed that children had the ability to detect and manipulate the component sounds that

comprise words at different grain sizes. They differ from dyslexic children who have difficulties to recognize

them. For instance, English dyslexic children showed disabilities to count the number of syllables and were

unable to manipulate syllables due to their lack of phonological representation. Therefore, the present study

aims to characterize the syllabic awareness of Indonesian dyslexic children. Five dyslexics from Pantara

Inclusive Primary School, Jakarta and 25 children from Kwitang 8 Primary School, Depok (chronological

age-matched control) were administered two experimental tasks: syllable counting and syllable reversal. This

study used quantitative and qualitative methods using a case control study. The instrument consisted of words

taken from the 10,000 highest frequency words in a linguistic corpus of Indonesian language. The results

generally suggested: 1) dyslexics found difficulties to count and replace syllables for words that have two and

three syllables; 2) dyslexics tended to alter CCV syllable to CV syllable; 3) dyslexics substituted phonemes

during syllable reversal task; and 3) four out of five control groups were unable to replace syllables in three-

syllable-reversal task. This study supports the phonological representation hypothesis of dyslexic children

suggested by Goswami (2010).

1 INTRODUCTION

Dyslexia is a specific learning difficulties and a

neurological condition caused by a different wiring of

the brain (dyslexiaida.org). Young children who have

been diagnosed with dyslexia normally have

language difficulties when they are three or four years

old. They tend to be late in talking, show unclear

speech, talk with a long-winded and unsystematic

speech, and have difficulties in distinguishing sounds

(Reid, 2011; Solek and Kristiantini, 2015). Therefore,

when they enter school, they generally have

difficulties in reading, spelling, writing (Lyon et al.,

2003), and speech perception (Brady et al., 1989;

Snowling, 2000; Ziegler, et al., 2009; Sitepu et al.,

2017). Dyslexics also seem to have difficulties to

identify syllables and letter sounds, and because of

those disabilities, they are considered lazy or stupid

(Hurford, 1998). In addition, most of those

difficulties are attributed to a deficit in phonological

awareness (Fawcett and Nicolson, 1995).

In terms of phonological awareness, Fawcett and

Nicolson (1995) defined phonological awareness as a

metalinguistic skill involving knowledge about the

sounds that make up words. However, it has been

suggested that dyslexics’ poor performance in

phonological awareness tasks may reflect

inaccuracies in the phonological representations of

the words that they are asked to analyze. Swan and

Goswami (1997) revealed that phonological

awareness skills of dyslexic children depend on the

accuracy of the underlying phonological

representations of words. Phonological awareness

develops as a natural part of language acquisition. At

the time children learn sounds, their brains develop

phonological representations of the sound structure of

individual words. Hence, normal children first gain

awareness of syllables when they turn to three years

old and they are able to distinguish syllable like /ba/

and /ga/ perceptually within the first month of life

(Goswami, 2010).

The ability of children to distinguish syllables has

been examined by Liberman et al (1974). They

measure the syllable awareness ability of American

children by asking them to clap their hands once for

words which have one syllable (i.e., dog), clap their

hands two times when they heard words which have

two syllables (i.e., tur-key), and clap their hands three

times for words that have three syllables (i.e., pres-i-

Sitepu, Y., Anjarningsih, H. and Laksman-Huntley, M.

Syllable Awareness of Indonesian Children with Developmental Dyslexia.

DOI: 10.5220/0007171706010606

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 601-606

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

601

dent). As a result, the criterion is passed by 90 per

cent of the 6-year-old children. Similar evidence of

success at the syllable level has been found by

Treiman and Baron (1981). It is reported that good

awareness of syllables was demonstrated by 5-year-

old American pre-readers when they were asked to

count the number of syllables. For instance, when

they were asked to count the number of syllable of

rabbit, the children were able to set out two counters.

Furthermore, Cossu et al (1988) asked Italian pre-

readers (aged 4-5, and 7-8) to tap out the number of

syllables in words like gatto ‘cat’, melone ‘melon’

and termometro ‘thermometer’. Criterion is also

reached by 80 per cent of the aged 5 children and 100

per cent of the school-age sample. Hoein et al (1995)

tested the Norwegian pre-schoolers using a similar

syllable-counting test, and the performance is 83 per

cent correct (i.e., telephone = 3 marks).

Based on the success at the syllable level by the

normal children and the differences with the children

who have reading disorders, Swan and Goswami

(1997) compared the phonological awareness skill of

English dyslexic children, poor readers and their

chronological age-matched control group by

administering syllable tapping task of words with one

syllable (e.g. clock, queen), three syllables (e.g.

hospital, potatoes) and four/five syllables (e.g.

television, electricity). The results suggested that

dyslexic children showed significantly lower syllable

awareness skill than the chronological age-matched

control (ps < .01), but were significantly higher than

the group of poor readers (p < 0.05) and all subjects

were equally proficient at the syllabic analysis of

short and long words.

Similar with the finding of Swan and Goswami

(1997), Bruck (1992) also found the same results with

dyslexic children selected from the patient population

of a clinic specializing in the assessment and

treatment of specific reading disorders. Children were

asked to listen to a non-word on a tape recorder and

then were asked to use blocks as counters to indicate

the number of syllables in the non-word. Bruck

(1992) found dyslexic children made more errors than

their chronological-age matched controls on all

phonological awareness measures, especially on the

syllable awareness, such as the dyslexic children

made syllable counting errors (f(1,26)=9,41, p<0,05).

Dyslexic children also made fewer overshoot

responses on digraph errors in the phoneme counting

task [f (1.26) =13.94, p<.0.01), and made single-letter

deletion responses on digraph errors in the deletion

task [f (1.13) =6.71, p<0, 05].

In line with the aforementioned investigations,

this study aims to characterize the syllable awareness

skill of Indonesian dyslexic children. These tasks are

devised to measure the syllable awareness of

Indonesian dyslexic children and their chronological

age-matched control groups, particularly analyzing

the children’s ability to recognize short and long

words containing simple consonant-vowel sounds

and consonant clusters. On the one hand, this study

will uncover new findings regarding the syllable

awareness of Indonesian dyslexic children and help

parents and therapists to examine the syllable

knowledge of children. On the other hand, the result

findings can show what kind of syllable is the most

difficult for dyslexic children. The scope is only on

the investigation of the production and recognition of

syllable awareness of Indonesian children by

administering them with syllable counting and

syllable reversal tasks.

In addition, based on the previous studies, it is

observed that results of normal children examined by

Treiman and Baron (1981), Cossu et al. (1988) and

the control group of Bruck (1992) are in line with

those of Goswami (2010). They differ from the

phonological awareness skill of dyslexics found by

Bruck (1992). The finding provides strong evidence

that dyslexic children suffer from a disorder in

syllable awareness skill which persists in 7 or 8-year-

old children. The comparison between the normal and

dyslexic children indicates that the children with

dyslexia are deficient in all areas of phonological

awareness. However, despite showing persisting

phonological awareness deficits of dyslexics

remaining as a crucial stumbling block for the

acquisition of fluent words recognition skills, the data

show that Bruck (1992) did not collect IQ or

intelligence level information for the normal children.

Moreover, Bruck (1992) asked children to count

the number of syllables in non-words that contained

two, three and four syllables. Along the same line, the

present study intends to see whether the Indonesian

children with dyslexia in an orthographically

transparent language also show poor performance in

syllable awareness like the findings of Bruck (1992),

and Swan and Goswami (1997). The current study

uses simple CV words and consonant clusters that

contain two and three syllables only. It is also

investigated whether any deficit uncovered also

reflects inaccuracies in the phonological

representations of the words as proposed by the

phonological representation hypothesis of Goswami

(2010).

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

602

2 METHODS

The method of this study is quantitative and

qualitative with a case control study approach.

Dyslexic children and control groups are observed

and interviewed. The children are administered with

two syllable awareness tasks: syllable counting and

syllable reversal tasks. Then, the correct answer is

counted. The syllable awareness skill of Indonesian

children with dyslexia is compared with the skill of

chronological age-matched control groups by using t-

test independent (SPSS). The children’s skill is

investigated by asking them to count the number of

syllables of 48 words (24 words with two syllables

and 24 words with three syllables, and the words

contain simple CV syllables and consonant clusters).

Examples of syllable counting and syllable reversal

for words with two syllables and simple words type

are bayi ‘baby’, daging ‘meat’, gizi ‘nutrition’; for

three syllables with clusters : drama ‘drama’, global

‘global’, gratis ‘for free’, three syllables for simple

words: merdeka ‘independent’, bakteri ‘bacteria’,

bendera ‘flag’; three syllables with clusters : promosi

‘promotion’, presiden ‘president’, pribadi ‘private’.

This study involves five Indonesian children with

dyslexia from Pantara Inclusive Primary School

based in Tebet, Jakarta. To qualify for the study, the

dyslexic children needed to attain an IQ score above

91 on the WISC-R (Wechsler, average IQ in

Wechsler ranging from 91 to 110), aged 7-9 (3 males

(aged 7-8), 2 females (aged 8-9)); living in an urban

area; speaking Bahasa Indonesia; and having parents

who graduated at least from high school. All the

children with dyslexia had been diagnosed as

dyslexics. The dyslexics are referred to as DA

(IQ=92), DB (IQ=92), DC (IQ=92), DD (IQ=96), DE

(IQ=93), and as for the control groups, CA, CB, CC,

CD and CE.

The chronological age-matched control group is

selected from Kwitang 8 Primary School, Pancoran

Mas, Depok. Inclusion criteria of the control group

are children aged 7 or who already studied in primary

school; without any psychological interference;

living in urban areas; having average level of

intelligence; having no speaking problems as

experienced by children with deafness or muteness;

and were fluent in Bahasa Indonesia. The intelligence

test for the control group was conducted in mass on

May 29th, 2017. None of the children selected for the

control group showed below-average level of

intelligence. The children were 7 years old (n=5), 8

years old (n=15) and 9 years old (n=5). The control

group selected shows the same age and sex with those

of children with dyslexia.

The test administrations is the following. First, the

children hear words on a recorder and clap their hands

as counters to indicate the number of syllables.

Second, the children are asked to move the last

syllable to the front of the words. All words used at

the syllable reversal task are similar with the words

used during the syllable counting task. All words used

in these tasks are taken from 10,000 words with the

highest frequency according to a linguistic corpus of

Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesianwac corpus) in 2016.

Subjects are tested individually. Two

experimental tasks are administered to all children,

among them: syllable counting and syllable reversal

test. As for the syllable counting tasks, subjects are

asked to count the number of syllables (clapping

hands) of words they hear from the recorder (i.e.,

simple words: bayi ‘baby’ (two times); merdeka

‘independent’ (three times); consonant clusters:

drama ‘drama’ (two times), presiden ‘president’

(three times). If children count the syllables

incorrectly or do not say anything, then the children

get a null score. Afterwards, they are asked to replace

the last syllable of each word and place the syllable to

become the first syllable. For example, when they are

asked to replace the last syllable of bayi (baby), they

have to say yiba. For the words which consist of three

syllables, when they are asked to replace the last

syllable of presiden (president), they have to move

den forward (become first syllable) and say denpresi.

3 FINDING AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Results of t-test Independent Test

The syllable counting and syllable reversal ability of

words with two syllables and three syllables of

dyslexic children are compared with that of control

group by using t-test independent statistic test. The

average score of syllable counting of the child with

dyslexia A (DA) with that of control group A (CA)

shows that for two syllable-words, mean DA=24,

SD=0; mean CA=23.00, SD=1.000, t=0.00, p=0.413

or p>0.05, and for three syllables: mean DA=0.00,

SD=0; mean CA=15.60, SD=5.899, t=-2.41, p=0.073

or p>0.05. As for the syllable reversal task, the result

shows mean DA=1.00, SD=0; mean CA=17.60,

SD=17.60, t=-2.08, p=0.105, or p>0.05; for the three

syllables, the result shows mean DA=0.00, SD=0;

mean CA=15,60, SD=5.899, t=-2.41, p=0.073 or

p>0.05, as for the control group, the result shows

mean DA=4.00, SD=0.

For DB compared with CB, the result of words

with two syllables shows mean DB=24.00, SD=0;

Syllable Awareness of Indonesian Children with Developmental Dyslexia

603

mean CB=23.20, SD=0.837, t=-19.33 p=0.43 or

p>0.05, and for words with three syllables, mean

DB=11.00, SD=0; mean CB=23.00, SD=1.000, t=-

20.82, p=0.000 or p<0.05. As for the syllable reversal

task of two syllables, the result shows mean DB=4.00,

SD=0; mean CB=18.00, SD=6.058, t=-2.230, p=0.90

or p>0.05, and for words which have three syllables,

mean DB=0.00, SD=0; mean CB=15.60, SD=5.899,

t=-2.41, p=0.073 or p>0.05.

For the comparison of the performance of DC

with that of CC, the statistic result shows mean

DC=24.00, SD=0; mean CC=23.20, SD=0.837,

t=0.873, p=0.432, or p>0.05, and for words which

have three syllables, mean DC=11.00, SD=0;

CC=23.00, SD=1.000, t=-10.954, p=0.000, or

p<0.000. As for the syllable reversal task, DC shows

mean=1.00, SD=0; mean CC=20.60, SD=2.074, t=-

6.62, p=0.001, or p<0.05; for the words which have

three syllables, mean DC=0.00, SD=0; mean

CC=17.20, SD=3.564, t=-4.40, p=0.012, or p<0.05.

For the comparison of the ability of DD with that

of CD, the statistic result in counting shows mean

DD=18.00, SD=0; mean CD=23.40, SD=0.894, t=-

5.51, p=0.005, or p<0.05, as for the result of three

syllables shows mean DD=7.00, SD=0; mean

CD=32.40, SD=0.894 t=-16.73, p=0.000, p<0.05. As

for the task of syllable reversal, the result shows mean

DD=17.00, SD=0; mean CD=11.80, SD=12.00,

t=0.39, p=0.713 or p>0.05; for the words which have

three syllables, the result shows mean DD=3.00,

SD=0; mean CD=11.60, SD=12.03, t=-0.65, p=0.550,

p>0.05.

In the comparison of the ability of DE with that of

CE, the statistic result in counting syllable of words

with two syllables shows mean DE=2.00, SD=0;

mean CE=21.20, SD=6.261, t=-2.79, p=0.049 or

p<0.05, as for the words of three syllables shows

mean DE=22.00, SD=0; mean CE=23.20, SD=1.789,

t=-0.61, p=0.573, p>0.05). For the task of replacing

syllables, DE shows mean DE=2.00, SD=0;

CE=24.00, SD=0.000, t=0; for the words which have

three syllables, the result shows mean DE=0.00,

SD=0; mean CE=22.60, SD=0.894, t=-23.06,

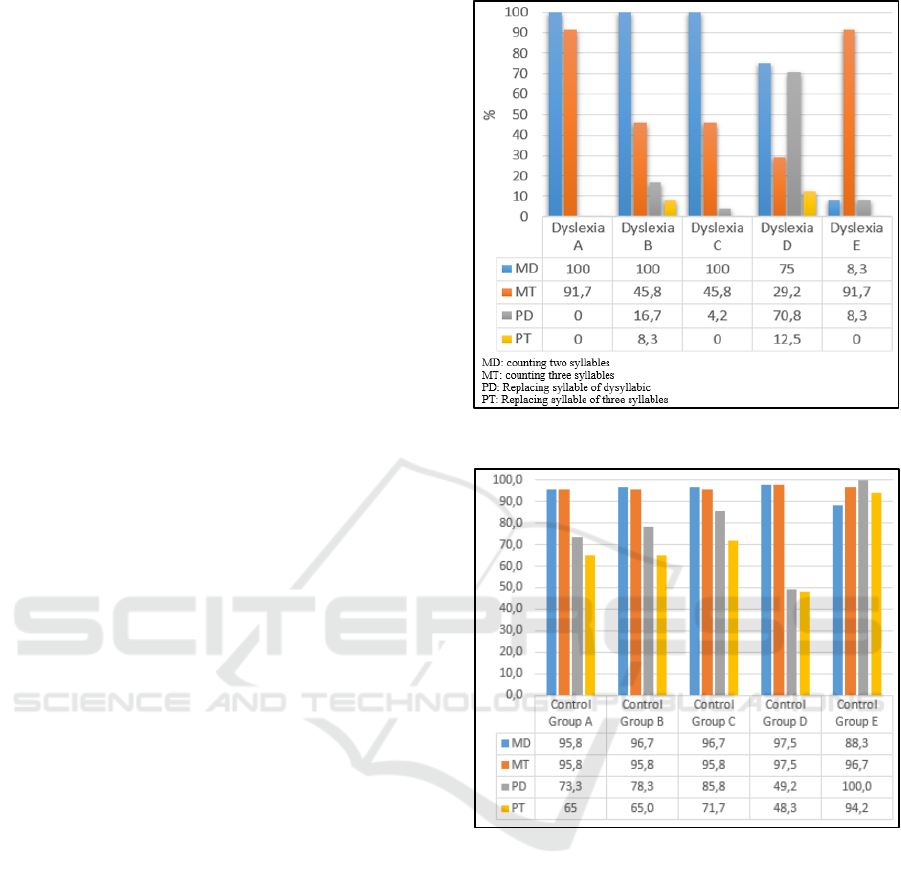

p=0.000, or p<0.05. In summary, 4 out of 5 children

with dyslexia have difficulty in syllable counting (see

figure 1) (DB, DC, DD, DE) and 2 out of 5 dyslexic

children have difficulties in syllable reversal task

(DB, DE). The percentage of syllable awareness skill

of Indonesian dyslexic children with the control

group can be seen at Figure 1 and 2.

Figure 1: Syllable awareness ability of dyslexic children.

Figure 2: Syllable awareness ability of control group.

Based on the aforesaid quantitative measures, the

present study’s results differ from the normal

children’s skill in general, similar with the finding of

Cossu et al. (1988) who ask Italian children aged 7-8-

year-old to tap out the number of syllables in words.

Criterion is reached by 100% of the school-age

sample, 80% of the 5-year-old, and 67% of the 4-

year-old. In addition, the present result is also

consistent with Treiman and Baron (1981, look at

Goswami, 2010) who found 90% of 6-year-old and

100% of 7-year-old succeeded to count the number of

syllables. The results also support Swan and

Goswami (1997) and Bruck (1992) who found that

the dyslexics show significantly lower results than the

chronological age-matched control in syllable

counting task. Although Bruck (1992) did not collect

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

604

the IQ data of normal children, this study shows that

the disability of dyslexics may not be confounded by

either IQ or intelligence level differences. Yet, the

present study is inconsistent with previous findings

suggesting that all subjects were equally proficient at

the syllabic analysis of short and long words, because

this study result shows that Indonesian dyslexic

children find difficulties to count syllables neither

short nor long words.

3.2 Results of the Qualitative Analysis

Based on the qualitative research, it is observed that

dyslexic children tend to change complex syllable

structures to become simple ones during the syllable

counting task. Two out of five dyslexic children also

tend to substitute vowels during the syllable reversal

task, but mostly, dyslexic children are not able to

replace syllable and they tend to shorten the length of

syllables.

3.3 Syllable Structure

Dyslexic children tend to alter syllable structure

during the syllable reversal task. They alter the

syllable structure of CVC to CCV [(DA; n=5), (DB;

n=5)]; CCV to CVC [(DC; n=1), (DD; n=2), (DE;

n=2)]; CV to CCV [(DA; n=1), (DB; n=4), (DC; n=1),

(DE; n=8)]; CV to CVC [(DA; n=1), (DB; n=2), (DC;

n=2), (DD; n=7), (DE; n=7)]; CVC to CV (DA;

n=13), (DB; n=9), (DC; n=8), (DD n=5) and (DE;

n=2)]. For instance: when DA is asked to replace sing

of the word pusing ‘dizzy‘ (CV-CVC) forward, he

answers sipung (CV-CVC) instead of singpu (CVC-

CV). As for the alteration of CCV to be CV, dyslexic

children tend to alter CCV to be CV syllables [(DA;

n=12), (DB; n=5) and (DC; n=3), (DE; n=16)]. For

instance, when DA is asked to replace fik of word

spesifik ‘specific‘ (CCV-CV-CVC), he says visiti

(CV-CV-CV) instead of fikspesi; and DB alters studi

‘study‘ (CCV-CV) to ditus (CV-CVC) instead of

distu.

3.4 Phoneme Substitution and Word

Addition

It is observed that DA and DB do not replace syllables

but tend to alter vowel sounds to /i/. DA alters /a/

sound to be /i/ (n= 24), /u/ sound to be /i/ (n=4), and

/ɛ/ to be /i/ (n= 14). For instance, planet ‘planet‘ to be

plipi; gratis ‘for free‘ to be gritis. As for DB, he alters

wanita ‘woman‘ to be ‘tiwani‘. The dyslexics also

show varying performances during the syllable

awareness tasks. The dyslexics cannot execute the

instruction syllable DA, DC and DE given by the

examiner. As for the syllable reversal task, they are

unable to replace syllables as instructed. For example,

when DE is asked to replace the syllable of the word

gratis ‘for free‘, she says oke instead of tisgra. For the

word kopi ‘coffee‘, DE says kopi pahit ‘bitter coffee‘

instead of piko.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Based on the results of this study, the difficulties to

distinguish syllable structure and to do syllable

segmentation indicated that Indonesian children with

dyslexia have phonological awareness deficit due to

their lack of phonological representation in the brain

(Goswami, 2010). Indonesian dyslexics find

difficulties to count the number of syllables for words

that have three syllables and contain simple syllable

structures and consonant clusters. Furthermore,

dyslexics also tend to substitute CVC and CCV to CV

syllables and substitute vowel sounds. Hence, the

study result is consistent with the finding of Swan and

Goswami (1997) that dyslexic children’s

performance in counting the number of syllables is

significantly lower than that of the control group, but

inconsistent with the finding stating that there is no

difference in the length of syllables. In addition, the

result also supports the finding of Bruck (1992) that

finds dyslexics are less successful than control group

in identifying words which contain simple syllable

structure. Moreover, the average ability of the control

group to count the number of syllable is 97%. This is

consistent with the ability of Italian children

suggested by Cossu et al (1988), and Treiman and

Baron (1981).

REFERENCES

Brady, S., Poggie, E., Rapala, M. M., 1989. Speech

repetition abilities in children who differ in reading

skill’. Language and Speech. 32(2), pp.109-122.

Bruck, M., 1992. Persistence of dyslexics: phonological

awareness deficits. Developmental Psychology. 28(5),

pp.874-886.

Cossu, G., Shankweiler, D., Liberman, I, Y., Katz, A. L.,

and Tola., G. 1988. Awareness of Phonological

Segments and reading ability of Italian children.

Applied Psycholinguistics. 9, pp.9-22.

Dyslexiaida.org., 2012. Definition of dyslexia, (Online)

Retrieved on October 2018 from:

https://dyslexiaida.org/dyslexia-at-a-glance.

Fawcett, A. J., Nicolson, R. I., 1995. Persistence of

phonological awareness deficits in older children with

dyslexia (Vol.7), p.361.

Syllable Awareness of Indonesian Children with Developmental Dyslexia

605

Goswami, U., 2010. A psycholinguistic grain size view of

reading acquisition across languages, In Nicola

Brunswick, Sine McDougall and Paul de Mornay

Davies (ed). Reading and Dyslexia in Different

Orthographies, Psychology Press. Hove.

Hoein, T., Lundberg, L., Stanovich, K. E., Bajaalid, I. K.,

1995. Components of phonological awareness. Reading

and Writing. 7, pp.171-188.

Hurford, D. M., 1998. To Read or Not to Read, A Lisa Drew

Book/Scribner. New York.

Liberman, I. Y., Shankweiler, D., Fischer, F. W., Carter, B.,

1974. Explisit syllable and phoneme segmentation in

the young child. Journal of Experimental Child

Psychology. 18, pp.201-202.

Lyon, G. R., Shaywitz, S. E., Shaywitz, B. A., 2003. A

definition of dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia. 53(1), pp.1-

14.

Reid, G., 2011. Special Educational Needs: Dyslexia 3rd

Edition (3), Continuum. London, GB.

Sitepu, Y., Anjarningsih H. S., Laksman-Huntley, M.,

2017. Nonword and Pseudoword Perception Deficit of

Indonesian Children With Dyslexia (Unpublished).

Solek, P., Kristiantini, D., 2015. Dyslexia today, Genius

Tomorrow, Dyslexia Association of Indonesia

Production. Bandung.

Snowling, M. J., 2000. Dyslexia, Blackwell publishing.

Swan, D., Goswami, U., 1997. Phonological awareness

deficits in developmental dyslexia and the phonological

representations hypothesis’. Journal of Experimental

Child Psychology. 66(1), pp.18-41.

Treiman, R., Baron, J., 1981. Segemental analysis:

Developmental and relation to reading ability, In G. C.

Mackinnon & T.G. Waller (Eds). Reading research

Advances in theory and practice, 3, pp. 159-198.

Academic Press. New York.

Ziegler, J. C., Pech‐Georgel, C., George, F., Lorenzi, C.,

2009. Speech‐perception‐in‐noise deficits in dyslexia.

Developmental science. 12(5), pp.732-745.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

606