A Cross-cultural Sociopragmatic Study

Apology Speech Act Realization Patterns in Indonesian, Sundanese, and Japanese

Nuria Haristiani

and Ari Arifin Danuwijaya

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Jl. Dr. Setiabudhi No. 229, Bandung, Indonesia

nuriaharist@upi.edu

Keywords: Cross-cultural, Sociopragmatic, Apology, Speech Act.

Abstract: In everyday life, when a person has performed an action of utterance which has offended another person, and

for which he can be held responsible, the person needs to apologize. However, in the cross-cultural context,

different rules and customs may apply according to its language and cultural background. This study examined

the differences and similarities of apology speech acts and strategies used in different cross-cultural contexts,

i.e., in Indonesian, Sundanese, and Japanese. The data on this research were collected using Discourse

Completion Test (DCT), which investigated four apology situations focused on the relations with the

interlocutors. The subjects of this study were 60 Japanese native speakers, 60 Indonesian native speakers, and

54 Sundanese native speakers. The collected data were then classified using Cross-Cultural Speech Act

Realization Pattern (CCSARP) coding scheme. The study findings revealed that Indonesian, Sundanese, and

Japanese native speakers used four similar strategies overall, but used different main strategies depending on

the relation with the interlocutor. Moreover, Indonesian and Japanese native speakers tend to express apology

in the highest frequency, whereas Sundanese native speakers tend to express their responsibility in the highest

frequency. Furthermore, the difference of apology speech act also showed in utterance level which indicates

the characteristics of each language. This study is expected to give a reference in speech act study, and help

understanding apology in cross-cultural context.

1 INTRODUCTION

Apology is a speech act intended to remedy the

offense for which the apologizer takes responsibility

and rebalance the social relations between

interlocutors (Holmes, 1990). In addition, it is also

perceived as a social event and is called for when

social norms have been violated whether the offence

is real or potential (Olshtain & Cohen, 1983). The act

of apologizing whether as ‘remedial work’ or social

events, requires an action or an utterance which is

intended to ‘set things right’ (Trosborg, 1987). Searle

(1965) claims that speech act is operated by universal

pragmatic principles and possible variations in

verbalization and conceptualization exist across

languages (Wierzbicka, 1985).

Several studies have attempted to analyse speech

acts across languages and cultures aiming at

investigating the existence of pragmatic universals

and their characteristics (e.g., Blum-Kulka,1989).

The result shows that concerning apologies, little

variation was found in the use of five main apologies

across languages studied. However, Olshtain (1989)

points out that similarities of expressing apology

(IFID) and preferences of expressing responsibility

from CCSARP data was surprising. It means that in

most situation, participants tend to express apology

and took responsibility of the offence. Regardless of

similarity pointed out from these results, there are

also possibility to find out different tendencies from

different languages with different cultures that

possess different rules. Furthermore, Blum-Kulka

(1989) also stated that studies of speech acts need to

move away from western languages and include as

many non-western languages and cultures in their

scope of study as possible.

Apology speech act in Japanese has been studied

from many points of view, such as analysing Japanese

apology strategies based on its semantic formulae

(Yamamoto, 2004; Sato, 2011; etc.), and also in

cross-cultural context such as in Japanese and English

(Barnlund and Yoshioka, 1990; Ikeda, 1993; Ootani,

2008;), Japanese and Chinese (Boyckman and Usami,

2005; Abe, 2006; etc.), Japanese and Korean (Jung

2011). However, there are only few cross-cultural

studies which compares apology speech acts in

Haristiani, N. and Danuwijaya, A.

A Cross-cultural Sociopragmatic Study - Apology Speech Act Realization Patterns in Indonesian, Sundanese, and Japanese.

DOI: 10.5220/0007166603130318

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 313-318

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

313

Indonesian and other languages, especially with

Japanese (Takadono, 1999; Haristiani, 2010), and

fewer in Sundanese and other languages. Therefore,

as an attempt to respond to Blum-Kulka’s (1989) call

to examine deeper about the characteristic of speech

act in non-western languages, this study aimed to

extract and categorize the range of strategies in the

speech act of apologizing in Indonesia, Sundanese

and Japanese as Asian languages, based on Blum and

Kulka’s (1984, 1989) CCSARP coding scheme and

main formulas.

2 RESEARCH METHOD

2.1 Participants

One hundred seventy two students took part in this

study, which include 60 Indonesian native speaker

(INS), 54 Sundanese native Speaker (SNS), and 60

Japanese Native Speakers (JNS). INS and SNS were

all students studying in different academic fields at

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, and JNS were all

students studying in different academic fields at

Hiroshima University. The average age of the

participants was 22.5 for INS, 22 for SNS, and 23

years old for JNS. The reason for choosing university

students was that in most studies on speech acts, the

participants had been university students. Thus, for

the sake of comparability of the results of this study

with the findings of the other studies carried out

around the world, collecting the data from a sample

of a similar population i.e., university students is

advisable (Afghari, 2007).

2.2 Data Collection

The data in this study were collected through an open

questionnaire which is a Discourse Completion Test

(DCT). The DCT used in this study included a brief

description of the situation. The situation in DCT was

a situation that university students are likely to

encounter in their daily language which is “Failed to

return book borrowed from interlocutor”. The two

main social factors specifically added in the situations,

i.e., social distance and social dominance. The social

distance is that the interlocutors either had a close

relationship (- distance) or hardly knew each other (+

distance). The social dominance or the power

relationship between the interlocutors inside the DCT

in this study was assigned only two values: status

equal (student-student), and status non-equal

(student-lecturer). All the interlocutors in the DCT is

set as follows: (1) Status un-equals, intimates:

Intimate Lecturer (IL), (2) Status un-equals, non-

intimates: Non-intimate Lecturer (NL), (3) Status

equals, intimates: Intimate Friend (IF), and (4) Status

equals, non-intimates: Non-intimate Friend (NF).

Data collected from DCT were then classified into

coding scheme from Cross-cultural Speech Act

Realization Project (CCSARP) by Blum-Kulka (1984,

1989), minus the “A promise of forbearance” (FORB).

3 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Coding Scheme of DCT Data

Based on CCSRAP coding scheme, the linguistic

realization of apology speech act can take the form of

five main strategies (Blum-Kulka, 1984, 1989;

Afghari, 2007). However, since the apology subject

in this study is about failing to return borrowed book,

“A promise of forbearance” (FORB) strategy mainly

replaced by “Promise to return the book” which

already included in “An offer of repair” (REPR).

Thus, the FORB strategy is not included in the coding

scheme in this study. According to the results from

DCT data, the apology strategies used by INS, SNS,

and JNS mainly including four (4) strategies based on

CCSARP coding scheme described as follows:

(Substantial English translation from utterance (E),

examples utterance taken from the data from three

languages in Indonesian (I), Sundanese (S) and

Japanese (J) with Japanese utterance’s reading in

alphabet are also provided)

1. An expression of an apology (use of IFID)

e.g. (E) I apologize

(I) Saya memohon maaf yang sebesar-

besarnya.

(S) Hapunten pisan Bu.

(J) 本当にすみませんでした。

(Hontouni sumimasendeshita)

2. An acknowledgement of responsibility (RESP)

e.g. (E) I forgot to bring the book.

(I) Buku yang kemarin saya pinjam itu lupa

dibawa hari ini.

(S) Abdi hilap teu nyandak bukuna.

(J) 今日返却の本を忘れてきてしまいま

した。(kyou henkyaku no hon o wasurete

kite shimaimashita)

3. An offer of repair (REPR)

e.g. (E) Can I return the book tomorrow?

(I) Bolehkah kalau saya bawa bukunya

besok saja?

(S) Upami enjing tiasa teu Bu?

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

314

(J) 明日お返ししてもよろしいでしょう

か。

(Ashita okaeshishitemo yoroshiideshouka)

4. Concern for the hearer (CONC)

e.g. (E) Do you need it today?

(I) Gimana emang butuh banget untuk hari

ini ya?

(S) Bukuna teu kacandak, bade enggal

dianggo?

(J) もしかして今日必要だった?

(Moshikashite kyou hitsuyoudatta?)

The first strategy which is “An expression of an

apology”, is the most direct realization of an apology

done via an explicit Illocutionary Force Indicating

Device (IFID) (Searle, 1969; Afghari 2007).

Furthermore, the main four strategies above consist

of a number of sub-formulas (sub-strategies), which

will not be discussed further in this paper.

3.2 Frequency Distribution of Apology

Strategies Used by INS, SNS, and

JNS

The data collected from DCT then classified into four

coding schemes of apology strategies and each

strategy’s frequency distribution is as seen in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that INS used the highest frequency of

apology strategies overall (715 times), followed by

JNS (689 times), and lastly by Sundanese (618).

Further, the sequence of most strategies used in INS

and SNS are similar, which are RESP (INS: 273 or

38.18%; SNS: 230 or 37.22%), at the highest

frequency, followed by IFID (INS: 255 or 35.66%;

SNS: 215 or 34.79%), then REPR (INS: 155 or

21.68%; SNS: 128 or 20.71%), and lastly by EXPL

(SNS: 32 or 4.48%; SNS: 45 or 7.28%). Meanwhile,

JNS used IFID most frequent (274 or 39.77%),

followed by RESP (229 or 33.24%), then REPR (148

or 21.48%) and lastly by EXPL (38 or 5.52%).

Table 1: Frequency distribution of apology strategies used

by INS, SNS and JNS (%).

INS SNS JNS

IFID

255 215 274

(35.66) (34.79) (39.77)

RESP

273 230 229

(38.18) (37.22) (33.24)

REPR 155 128 148

INS SNS JNS

(21.68) (20.71) (21.48)

EXPL

32 45 38

(4.48) (7.28) (5.52)

Total

715 618 689

(100) (100) (100)

Even though the most frequently used apology

strategy in three languages was slightly different, the

two most used apology strategies in all three

languages were the same: IFID and REPR. It seems

that, as also put by Trosborg (1987) and Afghari

(2007), the two strategies which are ‘directly

apologizing’ (IFID) and ‘showing responsibility’

(RESP), are the most frequently used apology

strategy in Indonesian, Sundanese and Japanese, as

well as in English and Persian. Several studies stated

that Indonesian tend to use many strategies in

frequent number while apologizing (Takadono, 1999;

Haristiani, 2010; etc.), and the result of this study also

showed the same tendency since Indonesian used

apology strategies in higher frequency compared to

the other two languages. Meanwhile, there are studies

reported that Japanese tend to use simple and small

amount of strategies in apologizing (Ikeda, 1993;

Abe, 2006; etc.). However, the results of this study

showed rather different tendency, since Japanese

native speaker used higher frequency of apology

strategies compared to Sundanese native speaker.

3.3 The Use of Apology Strategies by

INS, SNS, and JNS Based on the

Interlocutors

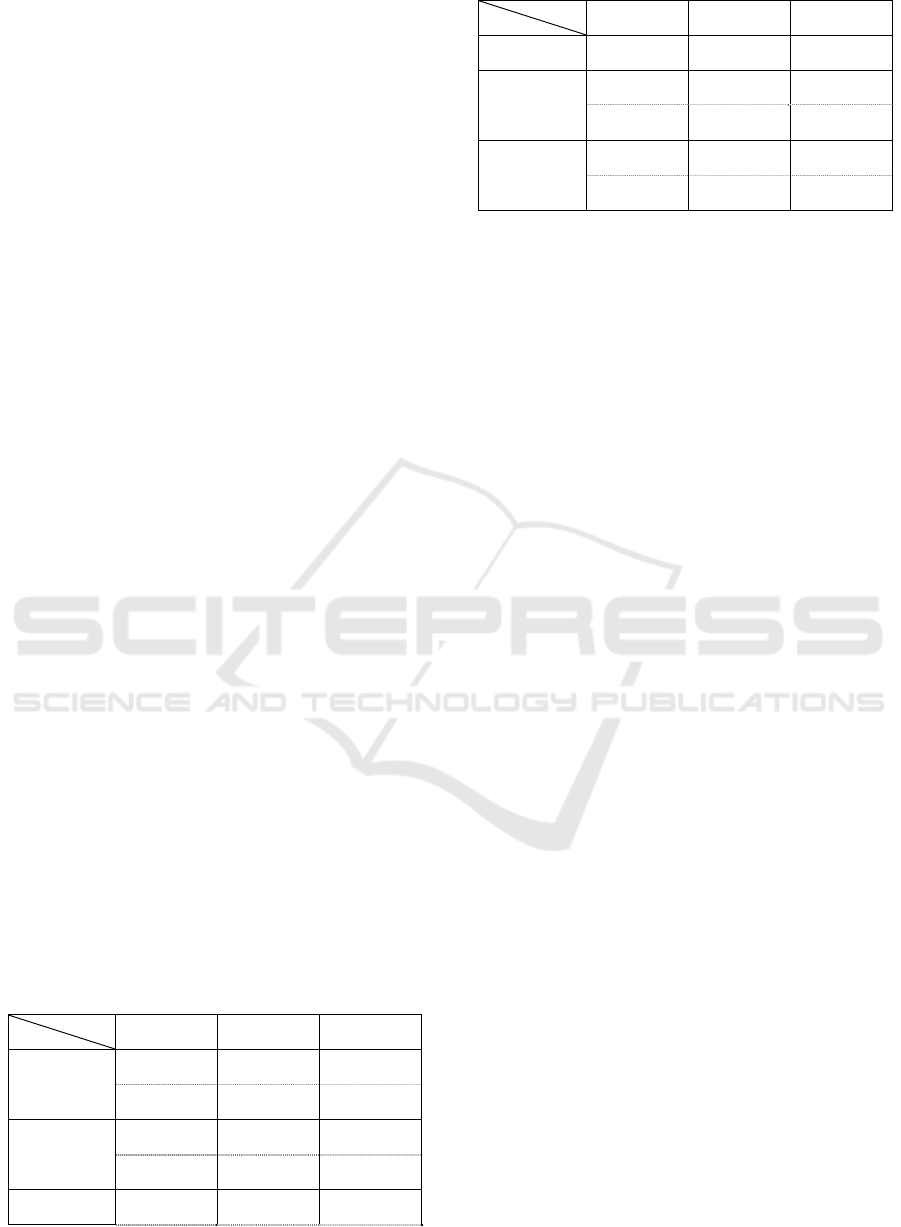

The use of four main apology strategies according to

the interlocutors in three languages is as seen on

figure 1 (a), (b) and figure 2 (a), (b). Figure 1 (a)

shows that when the interlocutor is an intimate

lecturer (IL), INS and JNS used IFID in the highest

frequency with a slight difference (INS: 37.71%;

JNS: 38.01%), followed by RESP as second frequent

strategy (INS: 32.57%; JNS: 35.09%), then REPR

(INS: 21.71%; JNS: 15.79%), and lastly EXPL (INS:

8%; JNS: 11.11%). Meanwhile, SNS used two

strategies as the most frequent strategies which are

IFID and RESP (37.91%), followed by REPR

(19.23%), and lastly EXPL (4.95%). Further, when

the interlocutor was a non-intimate lecturer (NL), ISN

and JNS again showed a highly similar tendency.

A Cross-cultural Sociopragmatic Study - Apology Speech Act Realization Patterns in Indonesian, Sundanese, and Japanese

315

Figure 1: Percentage of overall apology strategies used by

INS, SNS, and JNS to non-equal interlocutors (Lecturer).

Figure (a) shows apology strategies used to Intimate

Lecturer (IL), while (b) to Non-intimate Lecturer (NL).

In addition, as seen in Figure 1 (b), INS and JNS

used IFID the most (INS: 38.95%; JNS: 39.39%),

followed by RESP (INS: 33.16%; JNS:33.33%), then

REPR (INS: 17.89%; JNS: 18.18%), and lastly EXPL

(INS: 10%; JNS: 9.09%). Meanwhile SNS tend to use

RESP the most (38.80%), and followed by IFID

(37.70%) with only a slight difference. SNS then used

REPR (18.03%) and lastly EXPL (5.46%), which are

similar to other two languages.

From these data, it is understandable that in

Indonesian and Japanese, when apologizing to the

non-equal (+ power) interlocutors, expressing

apology is considered as the most important strategy.

While in Sundanese, both expressing apology and

responsibility are considered equally important, or

moreover expressing responsibility tend to be

considered as more important. The change of social

distance from intimate to non-intimate slightly

affected the use of main strategy in Sundanese, but

not in Indonesian and Japanese. However, in

Indonesian, the frequency of offering a repair tend to

be higher when the interlocutor is an intimate lecturer,

while in Japanese, offering a repair tend to be used

more to non-intimate lecturer.

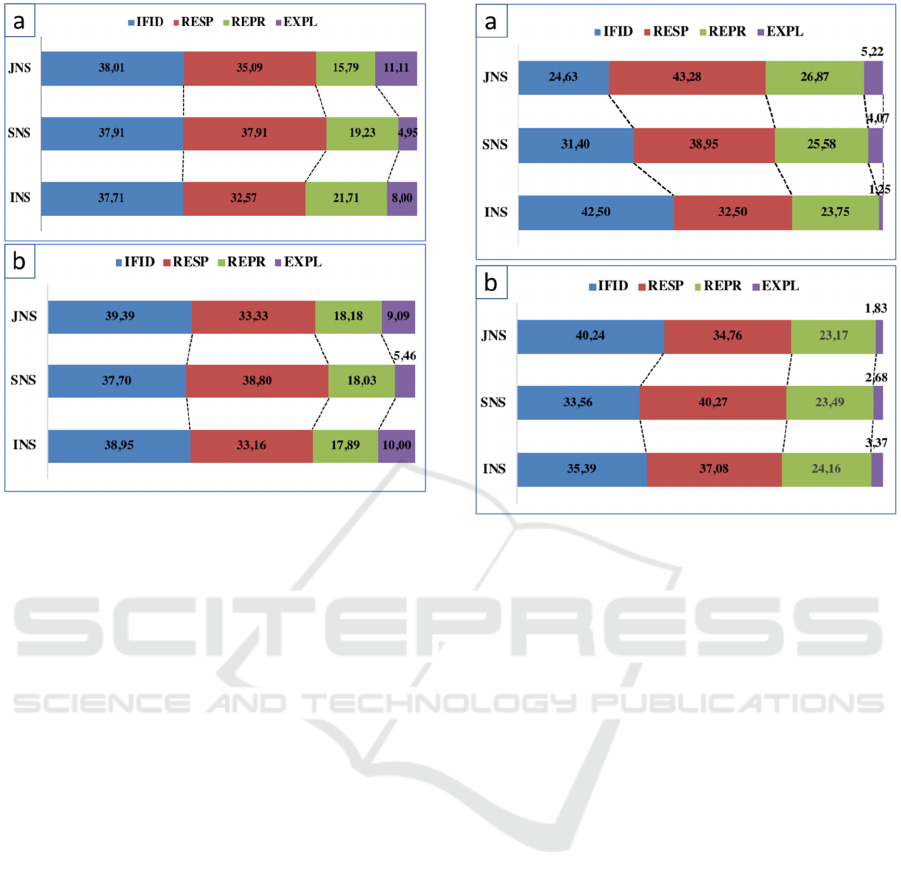

Figure 2: Percentage of overall apology strategies used by

INS, SNS, and JNS to equal interlocutors (Friend). Figure

(a) shows apology strategies used to Intimate Friend (IF),

while (b) to Non-intimate Friend (NF).

Further, in the situations where the interlocutor is

an equal, the use of apology strategies in three

languages showed different tendencies. As seen on

Figure 2 (a), to an intimate friend (IF), INS still used

IFID as the main strategy with significant frequency

(42.50%), followed by RESP (32.50%), while SNS

and JNS used REPR as the main strategy (SNS:

38.95%; JNS: 43.28%), followed by IFID (SNS:

31.40%; JNS: 24.63%). On the other hand, as seen in

figure 2 (b), to non-intimate friend (NF) INS and SNS

has the same tendency to use RESP as the main

strategy (INS: 37.08%; SNS: 40.27%), followed by

IFID (INS: 35.39%; SNS: 33.56%). While JNS used

IFID in the highest frequency (40.24%), and then

RESP (34.76%). Moreover, REPR and EXPL used in

a similar tendency in three languages, either when the

interlocutor is intimate (IF) or non-intimate (NF).

From above data, it can be seen that the use of

main apology strategies and its frequency to equal

interlocutors (friends) in Japanese and Indonesian

showed different tendency between intimate and non-

intimate interlocutors, but not in Sundanese. In

Japanese, when apologizing to an intimate friend,

expressing responsibility considered as the most

important strategy, while in Indonesian expressing

apology considered as the most important strategy.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

316

Meanwhile, when apologizing to non-intimate friend,

the most used strategy in Japanese changed to

expressing apology, while in Indonesian the most

frequently used strategy switched to expressing

responsibility. However in Sundanese, when

apologizing to both intimate and non-intimate equal

interlocutors, expressing responsibility is considered

as the most important strategy, regardless the social

distance or the intimacy difference.

The findings of this study show that Indonesian

and Japanese native speakers tend to distinguish the

use of most frequent strategies to the interlocutor

mainly influenced by the power dominance. When

the interlocutor is equal, the use of most frequent

strategy is also influenced by social distance.

Indonesian and Japanese also used apology

expression (IFID) in high frequency and tend to

repeat using IFID, which also stated in many previous

studies (Ikeda, 1993; Haristiani, 2010; Jung, 2011;

etc.). On the other hand, Sundanese native speakers

prefer to use the same main strategy, which is

expressing responsibility, to all interlocutors

regardless the difference in social dominance and

social distance.

However, besides the use of main four apology

strategies, the distinction of speech act also showed in

the level of utterance. For example, in Japanese that

has honorific forms, many expressions of apology

from the highest level of polite terms (sonkeigo) to

regular level form (futsuukei) such as Moushiwake

gozaimasen, Moushiwake arimasen, Sumimasen,

Gomen, Gomennasai, Warui, etc., were all used by

Japanese native speaker to express their apology

according to their relationship with the interlocutors.

Other than apology expression, the honorific forms

(sonkeigo, kenjougo, teineigo) in Japanese were also

used respectively in all utterance, mainly when the

interlocutor has higher social dominance. Meanwhile,

in Indonesian that has no structural honorific form,

the utterance distinction to different interlocutors

mostly showed by using address terms (Bapak/Ibu)

(Haristiani, 2012), and also by using indirect speech

(euphemism), which mainly used to interlocutors

with higher social dominance. On the other hand, in

Sundanese that also has structural honorific form

similar to Japanese, apology expression also used in

some forms with different level of politeness such as

Hapunten, Punten, Hampura, and Maap.

Furthermore, similar to Indonesian, in Sundanese,

address terms also used in high frequency especially

to interlocutors with higher social dominance. These

findings showed that even the use of main strategies

according to CCSARP coding scheme in these three

Asian languages did not show a striking difference

with those in European languages (Olshtain, 1989;

Holmes, 1990), the difference of speech act in three

languages found particularly in the level of utterance,

which indicates the characteristics of each language.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study aimed to extracting and categorizing the

range of main strategies used in performing speech

act in cross-cultural context which are in Indonesian,

Sundanese, and Japanese. This study also examined

the use of apology strategies according to the

relationship with the interlocutors, based on social

dominance (equal and non-equal), and social distance

(intimate and non-intimate).

The findings of this study indicate that in

Indonesian, Sundanese, and Japanese – as in the other

languages studying the western (Olshtain and Cohen,

1983) and non-western (Afghari, 2007), apologies

generally fit within the framework of the categories

explored and discovered in western studies. Also,

expressing of apology directly and an acknowledging

responsibility were found to be the most frequent

apology strategies used to all interlocutors in all three

languages. However, the expression of apology

mainly used most in Indonesian and Japanese, while

acknowledging responsibility was Sundanese most

used strategy. Furthermore, the characteristic of

apology speech act of each language in this study also

reflected in the utterance level, which shows the

characteristic of Japanese and Sundanese which has

structural honorific forms, and Indonesian which

doesn't have honorific forms, structurally.

Lastly, this study succeeded in categorizing

apology speech act strategies based on CCSARP

main formulas. However, to understand deeper about

the characteristic of apology speech act in each

language in the cross-cultural context, the sub-

formula (sub-strategies) is also significant to be

analyzed further in the next study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper acknowledged the students in Universitas

Pendidikan Indonesia and Hiroshima University that

has participated in data collection in this study. This

paper also acknowledged Universitas Pendidikan

Indonesia for providing research fund through

Bangdos (Grant: Afirmasi).

A Cross-cultural Sociopragmatic Study - Apology Speech Act Realization Patterns in Indonesian, Sundanese, and Japanese

317

REFERENCES

Abe, K. 2006. Shazai no Nicchuu Taishou Kenkyuu. Thesis

in Hiroshima University, unpublished.

Afghari, A. 2007. A sociopragmatic study of apology

speech act realization patterns in Persian. Speech

Communication, 49, pp. 177-185.

Barnlund, D. C., Yoshioka, M. 1990. Apologies: Japanese

and American styles. International Journal of

Intercultural Relations, 14, pp. 193-206.

Blum-Kulka S., House J. 1984. Request and Apologies: A

cross cultural study of speech act realization patterns

(CCSARP). Applied Linguistics, 5 (3), pp. 196-214

Blum-Kulka S., House J. 1989. Cross-Cultural and

Situational Variation in Requesting Behaviour. In S.

Blum-Kulka, J. House and G. Kasper (Eds.). Cross-

Cultural Pragmatics: Request and Apologies. Norwood,

NJ: Ablex, pp. 123-154

Boyckman, S., Usami, Y. 2005. Yuujinkan de no Shazaiji

ni Mochiirareru Goyouron teki Housaku: Nihongo

bogo washa to Chuugokugo bogo washa no hikaku.

Goyouron Kenkyuu, 7, pp 31-44

Haristiani, N. 2010. Indonesiago to Nihongo no

Shazaikoudou no Taishoukenkyu – Shazaibamen to

Gokaibamen ni okeru feisu no ijihouryaku ni

chakumokushite, Thesis in Hiroshima University,

unpublished.

Haristiani, N. 2012. Indonesia go to Nihongo no koshou no

hikaku – Shazai bamen ni mirareru jishoushi-taishoushi

no taiguuteki kinou ni chakumokushite, Sogogakujutsu

gakkaishi, 11, pp. 19-26

Holmes, J. 1990. Apologies in New Zealand English. Lang.

Soc., 19, pp. 155-200.

Ikeda, R. 1993. Shazai no Taishoukenkyuu: Nichibei

Taishoukenkyuu - Face to iu shiten kara no kousatsu -.

Nihongogaku, 12(11), pp 13-21.

Jung, H. A. 2011. Shazaikoudou to Sono Hannou ni

kansuru Nikkan Taishoukenkyuu: Poraitonesu riron no

kanten kara, Gengo Chiiki Bunka Kenkyuu, 17, pp 95-

112.

Olshtain, E., Cohen, A. 1983. Apology: A speech act set. In

Wolfson, N., Judd, E. (Eds) Sociolingusitics and

Language Acquisition. Newburry House, Rowly. MA.

Olshtain, E. 1989. Apologies Across Languages. In S.

Blum-Kulka, J. House and G. Kasper (Eds.). Cross-

Cultural Pragmatics: Request and Apologies. Norwood,

NJ: Ablex, pp. 155-173

Ootani, M. 2008. Shazaikenkyuu no Gaikan to Kongo no

Kadai: Nihongo to Eigo no taishoukenkyuu o chuushin

toshita kousatsu. Gengo Bunka to Nihongo Kyouiku.

Zoukan tokushuugo, pp 24-43.

Sato, A. 2011. Gendai Nihongo no Shazai Kotoba ni

kansuru Kenkyu. Iwate Daigaku Daigakuin

Jinbunshakaikagaku Kenkyuka Kiyo, 20, pp. 21-38.

Searle, J. 1969. Speech acts. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Takadono, Y. 1999. Nihongo to Indonesiago ni okeru

Shazai no Hikaku. Indonesiago to Bunka, 5, pp 27-50

Trosborg, A. 1987. Apology Strategies in Natives/Non-

Natives. Journal of Pragmatics, 11, pp. 147-167.

Wierzbicka, A. 1985. Different cultures, different

languages and different speech acts. Journal of

Pragmatics, 9, pp. 145-178

Yamamoto, T. 2004. Shakaiteki sougo koui toshite no

shazaihyougen – gengohyougen sentaku no haikei ni

wa naniga aruka- Shinshuu Daigaku Ryuugakusei Senta

Kiyo, 5, pp. 19-31.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

318