A Study on the Japanese Adverbs “Zenzen” and “Mattaku” in Terms

of Pragmatics

Anggia Septiani Putri and Nuria Haristiani

Postgraduate School of Japanese Language Education Department, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia

anggia.septiani@student.upi.edu

Keywords: Complete Negation, Adverbs, Pragmatical Function.

Abstract: Japanese is known as one of the complex languages which has many ruigigo (synonyms). “Zenzen” and

“mattaku” are adverbs that are also synonyms, and they have the same meanings which are complete

negations. In English, those have the same meanings as “not at all”. However, lately, many younger people

use it to express positive responses indicating that the meaning and function of these adverbs had already

changed pragmatically. This pragmatical change becomes a challenge for Japanese learner and it is important

to be studied further to prevent misuse which can lead to misunderstanding on the usage of these adverbs.

This study aimed to examine pragmatic function changes on adverbs “zenzen” and “mattaku”. The data of

this study were collected from Corpus Spontaneous Japanese. The data of these adverbs were then sorted into

three types: negation, negative conotations, and new function. Then, the data were analyzed using descriptive

analysis method. The result of this study showed that it could be understood that the negative

connotations had huge frequency on the “zenzen” and “mattaku” functions. “Zenzen” was mostly

used for something that is relative and could be changed if seen from different point of view, while “mattaku”

is absolute no matter what, and also “mattaku” has a tendency to underestimate something.

1 INTRODUCTION

Japanese is a complex language that has different

syntax, grammar structure, and writing system from

another language. Written Japanese is complex and

inherently ambiguous for many reasons. Writing or

typing Japanese typically involves the use of a

combination of three orthographic scripts—kanji,

katakana, and hiragana. (Bjarnestam, 2009).

Also, Japanese has many words with same

meaning (synonims) called ruigigo. To understand

what the meaning of these synonyms, learners should

know the whole of context of the sentences. The

distributional hypothesis states that words with

similar meanings tend to appear in similar context

(Harris, 1968).

This study discussed about “zenzen” and

“mattaku´ which have same meaning as a negation in

negative context. In English these words have the

same meaning with “not at all”, “completely”, and

“any”. “Zenzen” and “mattaku” are located on the

scale of gradient from degree to intensity (Yamauchi,

2012). Even though that these adverbs have negative

meaning, lately many young people use it to express

the postive response which means there is a language

change happening.

This language change can cause many problems

for Japanese learners. Because what they learned in

the class could be different from what is being used

in reality. Many studies show learners to be highly

sensitive to pragmatic in function (Ohta, 2001).

Students are often trained with “academic”

vocabulary. Even though many students establish a

non-academic vocabulary they still need to be able to

distinguish between functional and non-functional

language (Solano-Flores, 2006). But, not only for

Japanese learner, can this language change be a

problem for the teacher too. Therefore, this study of

“Zenzen” and “Mattaku” is important to be discussed

to prevent misuse which can lead to misunderstanding

on the usage of these adverbs.

Some Japanese language learners sent to Japan

will experience obstacles in interpreting the meaning

of the word zenzen and mattaku. Not only had the

limitations of knowledge possessed but also because

its use has changed. Changes in written language

occur but not very significantly as occurs in spoken

language. So research on zenzen and mattaku adverbs

should be investigated to prevent errors in their use

24

Putri, A. and Haristiani, N.

A Study on the Japanese Adverbs “Zenzen” and “Mattaku” in Terms of Pragmatics.

DOI: 10.5220/0007161400240029

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 24-29

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

which can lead to misunderstandings in meaning

interpretations.

The use and change of zenzen and mattaku can be

investigated using its pragmatic function and seen

how it relates to one adverb with another adverb.

Therefore, the authors raised this topic into the theme

of research.

2 JAPANESE ADVERBS

There are Japanese adverbs that contain negative

meaning which have always been used in negative

context sentence. For example, in Japanese nouns,

“nanimo” (nothing) ,”dare mo” (nobody), and

“dokomo” (anywhere) which have “mo” (also in

negative meaning) particle behind. Another example

is “shika~nai” (only-neg.), “kessite~nai” (never) and

“kanarazushi mo~nai” (necessarily), these negative

adverbs are followed by “~nai” which have minus

image in the sentence. In English, the words that have

a negative meaning are any (anybody, anything,

anymore), ever, yet, and at all (Sano, 2012).

The opposite of this expression is positive adverb,

like “kanarazu” (certainly) in Japanese and some

(somebody, someone, somewhere) in English.

‘Zenzen” and “mattaku” including to Japanese

gradable adverbs. Gradable adverb is connected with

norm aberration, marking a ‘more than the norm’ or

‘less than the norm’ situation. Intensification is not

only norm deflection, but also a kind of evaluation.

The role of context is by all means of paramount

importance when defining positive or negative types

of evaluation (Subich et al, 2014)

2.1 The Function of “Zenzen”

Zenzen is one of the negative polarity items

(hiteikyokuseikoumoku), also known in Japanese

grammar as chinjutsufukushi or statement adverb

(Sano, 2012). So, the word after zenzen, it always has

negative words such as ~nai (negative form in

Japanese).

In the late Meiji period up until the early Showa

period, the usage included both negative and

affirmative functions (Yamada 2014). In early

Showa, the use of zenzen in conjunction with an

affirmative word was deemed incorrect for unknown

reasons and this usage dropped (Suzuki, 1993).

However, lately, there has been an increase in the

affirmative usage of zenzen. The use of zenzen with

affirmation is observed especially among the younger

generation, and it occurs with adjectives or adverbs to

emphasize degrees, as in example (1).

Example (1)

このケーキは全然{美味しい・美味しくない}

Kono Keeki wa zenzen {oishii / oishikunai}.

This cake (tasty / untasty) at all.

Both can be used in the use of the word zenzen in

this modern. In contrast to the period of showa which

strongly prohibits the use of the word zenzen in a

positive response even if only for affirmation.

Younger people recently use expressions such as

zenzen daijoubu (absolutely fine), zenzen OK

(absolutely OK) or zenzen ii (absolutely good)

frequently in spoken language. The “zenzen +

positive word” usage which has increased in recent

years often contains more modern expressions, but it

is still seems to be the same affirmative usage that

used more than 100 years ago (Wallgren, 2015).

That positive function was never used before in

Japanese. But nowadays, many people is using it even

they know that function is wrong grammatically. But

it can be used in pragmatic view.

2.2 The Function of “Mattaku”

Sunagawa (1998, p.544) cited that mattaku divided to

be two types: mattaku with “~nai” ending and

mattaku that emphasizes the degree. The meaning of

Mattaku can be seen from the words that followed.

“Mattaku + negative functions” mean it emphasizes

the overall negative meaning.

Mattaku which has almost the same meaning as

totemo, used to emphasize the degree and show

feelings about emphasis on facts / assessments.

Mattaku which shows meaning similar to “sukkari”

(entirely) is something that entirely takes place like

conditions at that time. Mattaku in the function of

“mattakuda” and “mattakudesu” used to strengthen

confession or disclaimer of the other person’s words

in the conversation. The category of Mattaku can be

divided into 4 groups, there are:

1) Adverbia mattaku which followed by negative

form words such as nai, zu, nashi, mai, n or

negative expressions such as dame, mu ~, fu ~ ..

Emphasizing the overall negative meaning.

2) Adverbia mattaku which has almost the same

meaning as totemo 'very' hontouni 'really' and jitsu

ni 'really'. In this category also includes mattaku

with the addition of particle no in mattakuno.

Used to emphasize degrees and show feelings

about emphasis on facts / judgments.

A Study on the Japanese Adverbs “Zenzen” and “Mattaku” in Terms of Pragmatics

25

3) Adverbia mattaku which shows the meaning

similar to 'full' in sukkari is something that

entirely occurs as the condition at that time.

4) Adverbia mattaku in the form of mattakuda,

mattakudesu and others to respond to the words of

the opponent that shows the meaning of

strengthening the recognition or denial of the

speaker's words in the conversation.

3 RESEARCH METHODS

Pragmatics has traditionally been a field of qualitative

rather than quantitative analysis, and also a field

where detailed micro-analyses of small pieces of data

were more common than generalisations over large

bodies of data. Pragmatic aspects of language are

usually best studied on authentic and spontaneous

data (Schmidt & Worner, 2009). The data produced

in this study is qualitative data in the form of

sentences derived from the instrument data obtained

from Corpus Spontaneus Japanese (CSJ). Therefore

the authors use qualitative descriptive method in this

study.

CSJ is a voice corpus made by National Institute

for Japanese Language, Information and

Telecommunication Research of Tokyo Institute of

Technology. CSJ contains 661 hours of voice records

including the script. It can be used for linguistic,

phonetic, Japanese, Japanese education research

(Sano, 2012). Some Japanese researcher is using this

corpus because it has actual data and there is renewal

for the program. The data inside CSJ is taken from

television scripts, radio scripts, and also the data from

the previous researches.

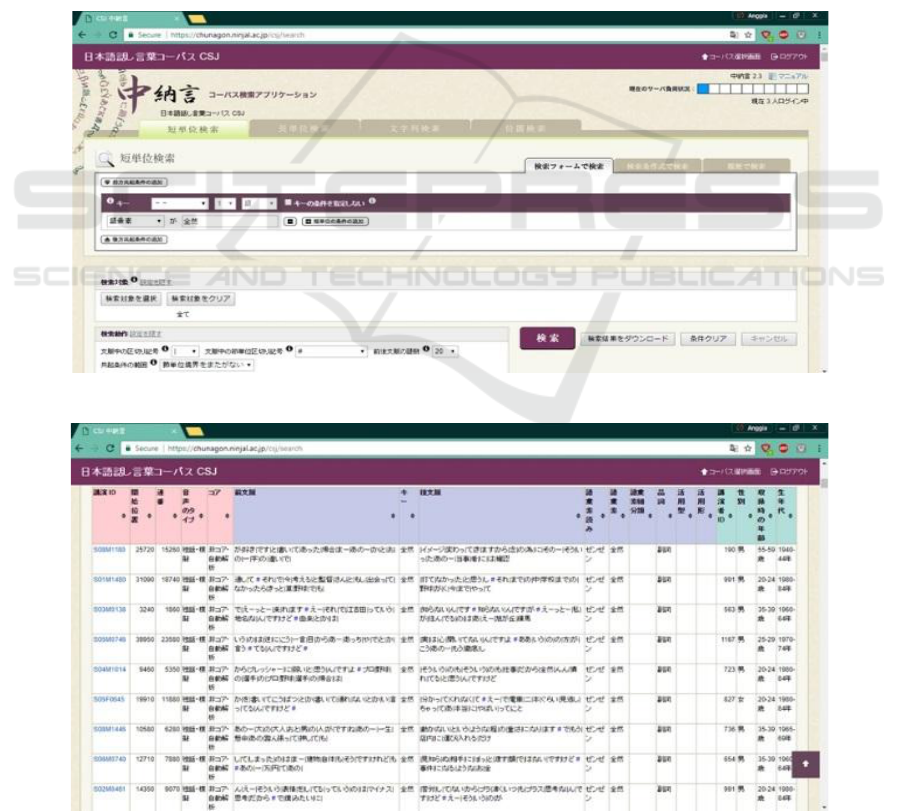

Figure 1: Layout of Corpus Spontaneous Japanese.

Figure 2: Layout of Corpus Spontaneous Japanese.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

26

First, we classified all of the sentences that use

zenzen and mattaku words in oral Japanese corpus

system or Corpus Spontaneous Japanese. The data is

script of the conversations which are available in

Corpus Spontaneous Japanese program.

After all of the data has been collected, it was

sorted to 3 types: negation, negative connotations and

new function. Negation function is the one which

followed by ~nai. Negative connotations function is

the affirmative words such as chigau (different),

dame (useless), betsu (another or distinction), etc.

Lastly, the new function is the positive response d

function like ii (good), daijobu (all right), heiki

(unconcern), and more.

Then, it using the distributional and change

methods to distinguish the use of the word zenzen and

mattaku. After that, we compared of the differences

and similarities of the use of zenzen and mattaku

annotations obtained from corpus and summed up the

result of the research.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

There are 7.608.368 words available on CSJ program,

and there could be found 1704 words of zenzen and

1435 words of mattaku. Then, zenzen and mattaku

function sorted into three groups, negation (~nai or

~masen), negative connotation (dame, chigau, etc)

and new function (positive functions). Then it was

analysed based on pragmatic functions with

descriptive analytic using distributional and change

method.

The figures (3) and (4) show about the function of

zenzen and mattaku in Japanese daily life

conversation. Japanese tend to use zenzen and

mattaku as a negation and avoid the positive function

of these adverbs.

Figure 3: The Function of Zenzen.

Figure 4: The Function of Mattaku.

Figure (3) shows that the function of zenzen as

negation has the highest frequency, 78% or used 1334

times. Negative connotation only appeared 19% or

320 times, and the new function used only 3% or 50

times. While Figure (4) shows that Japanese tend to

us mattaku as negation is high. The negation function

appeared 75% equals to 1.084 times, negative

connotation function appeared 10% equals to 137

times, and new function appeared 15% equals to 214

times. According to data from figure 1 and figure 2,

zenzen’s new function is being used less than its

negative connotation while on the contrary, mattaku

as a new function is being used more than its negative

connotation.

From figure (3) and (4), it can be understood that

the negative connotations has huge frequency on the

“zenzen” and “mattaku” function.

The data in this section from Examples (2) until

(7) is analysed based on the 3 different function of

zenzen and mattaku that has been aforementioned

above, negation, negative connotation and new

function.

Example (2)

その行き方が全く分からなくて地図とか見てい

ても全然分からない。

Sono ikikata ga mattaku wakaranakute chizutoka

miteitemo zenzen wakaranai.

I do not understand the directions (at all) and I do not

understand it at all even if I look at a map (Women,

25-29 years old).

Example (2) shows the usage of negative context

shown by the using of ~nai following the usage of

zenzen and mattaku. The using of “mattaku/zenzen +

wakaranai” could be found in CSJ, there are 545

usages of mattaku and 743 usages of zenzen. On

example (2) we could see 2 different function of

zenzen and mattaku on 1 sentence, the meaning of

those 2 phrases are different, the one with “mattaku

wakaranai” means that the speaker did not

understand and the “zenzen wakaranai” means that

78%

19%

3%

Negation

Negative

Connotation

New Function

75%

10%

15%

Negation

Negative

Connotation

New Function

A Study on the Japanese Adverbs “Zenzen” and “Mattaku” in Terms of Pragmatics

27

the speaker has did some effort but the speaker still

do not understand.

Example (3)

それまでは海外での生活と言うか仕事の経験全

くありませんでした。

Soremade wa kaigai de no seikatsu to iu ka shigoto

no keiken mattaku arimasendeshita.

Until then I have no experience of work or job abroad

(Men, 55-59 years old).

Example (4)

そんなに悪いことなんか言ってる訳では全然あ

りませんでした。

Sonnani waruikoto nanka itteruwaku dewa zenzen

arimasen deshita.

I was not saying anything bad (Women, 45-49 years

old).

Example (3) and (4) shows the usage of negative

sentence shown by the using of “arimasen” following

the use of zenzen and mattaku. In the CSJ could be

found 28 sentences using “zenzen arimasen” and 56

sentences using “mattaku arimasen”. Although both

sentences are using arimasen but their meaning are

different from each other. From example (3) we could

see that the speaker dont have any experience of

working abroad for his whole life, while the usage of

“zenzen arimasen” on example (4) could mean

relative, she did not say anything bad at the time but

has probably say something bad before at one point

of her life.

Example (5)

父親に座ってもらったりするんですけれどもも

う全然ダメですね。

Chichioya ni suwatte morattari surundesukeredomo

mou zenzen damedesune.

I have my father sit down, but it’s no good at all

(Women, 25-29 years old).

Example (6)

女性二人というのがもう全く英語がダメです。

Jousei futari toiu no ga mou mattaku eigo ga dame

desu.

Those two girls are really bad at english (Women, 30-

34 years old)

The usage of “zenzen/mattaku + dame” is for

showing a negative connotation. “Dame” has the

same meaning with “yokunai” (it is not good). In the

CSJ There are 18 sentences using “zenzen dame” and

6 sentences using “mattaku dame”. In example (5),

the speaker said that the speaker has did some effort

but it is pretty much useless, while on example (6) the

speaker said that the object being talked about by the

speaker is not good or bad at something and the

speaker could do nothing about it. This result is

reinforced by Taguchi (2009) theory. According to

Taguchi, the usage of mattaku is often used following

the feeling of emotion within the speaker because of

its function as a strong negation.

Example (7)

俺の一年だったともう全然大丈夫だよ。

Boku no ichinendatta to mou zenzen daijoubudayo.

My whole year have no problem. (Men, 20-24 years

old)

In CSJ could be found 18 sentences using “zenzen

daijoubu” but no usage of “mattaku daijoubu” could

be found. Example (7) shows that the speaker dont

have any problem at all, but the usage of “zenzen

daijoubu” could mean relative as there are probably

some minor problem on the speaker’s year, and there

is no way that one person could get through a year

without any single problem at all, because of that

mattaku could not be used because mattaku is

absolute.

Seeing example (2) through (7) we could

understand that zenzen mostly being used for

something that is relative and could be changed if

seen from different point of view while mattaku is

absolut no matter what, and also mattaku has a

tendency to underestimate something.

Despite the changes in use in both adverbs, the use

of positive meanings is more commonly found in the

use of mattaku. Conversely, positive words that have

a negative meaning can be seen in the use of zenzen.

Therefore, we can know that the use of zenzen

using a positive word has a denial of the previous

sentence as seen in example (7) which shows that

there is a denial that life is not working. Although

logically, it is impossible for a person to have no

problems throughout the year in his life.

While the use of mattaku has an emphasis for the

sentence that explained. As the phrase described in

examples (5) and (6) in which example (6) has an

emphasis and satire on a third party, and he cannot do

anything for the object of speech. Where example (5)

shows more of an effort and point of view of the

speaker.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study is focusing on the function of zenzen and

mattaku on different usage such as negative

connotation, negation and new function. For both

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

28

zenzen and mattaku. Its usage as a negation is the

most used one, while on the negative connotation and

new function they got different result. Zenzen is

mostly being used on a negative connotation while on

the contrary mattaku is mostly being used by its new

function as a positive connotation. Zenzen is mostly

being used on something that is relative or temporary

from the speaker’s point of view while mattaku tend

to be something that is absolute no matter from what

point of view.

REFERENCES

Bjarnestam et al., 2009. Content Search in Complex

Language, Such as Japanese. U.S Patent and

Trademark Office. Seattle

Harris, Z.S., 1968. Mathematical Structures of

Language.Wiley. New York.

Hibiya, J., Takano, S., Matsuda, K., Sano, S., Hattori, N.

and Oota, I., 2012. Hajimete Manabu

Shakaigengogaku, Minerva. Kyoto.

Ohta, A.S., 2001. Second Language Acquisition Processes

in the Classroom: Learning Japanese. Routledge.

Washington.

Schmidt, T., Worner, K., 2009. EXMARaLDA - Creating,

Analysing, and Sharing Spoken Language Corpora for

Pragmatic Research. In Pragmatics. International

Pragmatic Association.

Solano-Flores, G. 2006. Language, Dialect, and Register:

Sociolinguistics and the Estimation of Measurement

Error in the Testing of English Language Learners,

Teachers College Record. New York.

Subich et al., 2014. Gradability and intensification of the

language quantity (on the materials of English, Russian

and Japanese). in Life Science Journal. Russia.

Sunagawa, Y., 2000. Kyoushi to Gakushuusha no Tame no

Nihongo Bunkei Jiten. Kurosio. Tokyo.

Suzuki,H. 1993. Kango no Ukeire nit suite “Zenzen” wo rei

toshite. Matsumura Akira Sensei Kiju Kinenkaihen

[Kokugo Kenkyuu]. MEIJI SHOIN. pp. 428-449.

Wallgren, J., 2015. Attitudes Towards and Uses of the

Japanese Adverb Zenzen by Swedish Learners of

Japanese. Dalarna University Thesis. Unpublished.

Taguchi, N., 2009. Pragmatic Competence. Walter de

Gruyter GmbH 7 Co. KG. New York.

Yamada, S., 2014. Yoku Aru Kotoba no Shitsumon.

National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistic

Yamauchi, N., 2012. English Looks at Japanese and Vice

Versa: A Contrastive Approach to Intensifiers in

English and Japanese. Journal of Culture and

Infunctionation Science, 7(2). pp 1-12.

A Study on the Japanese Adverbs “Zenzen” and “Mattaku” in Terms of Pragmatics

29