Does Identity Status Influence Marriage Readiness Among Early

Adults in Bandung City?

Ifa Hanifah Misbach, Syahnur Rahman and Lira Fessia Damaianti

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Jl. Dr. Setiabudhi No. 229, Bandung, Indonesia

ifahmisbach@gmail.com

Keywords: Identity Status, Marriage Readiness.

Abstract: This study aims to identify the influence between identity status toward marriage readiness among early adult

in Bandung, West Java. This study used quantitative method. The sample selected by purposive sampling

technique with 118 subjects between 21-45 years old. The instrument used to collect the data of identity status

was Ego Identity Process Questionnaire (EIPQ) and marriage readiness was Personal Readiness Scale (PREP-

M). The data analysis used in this research was Multiple Regression technique. Results of this study show

influence between identity status toward marriage readiness with coefficient correlation of 0.399 (F=10.888,

p<0.05), thereby, marriage readiness variation explained by identity status are 15.9% (r2 = 0.159). Then, there

was a difference found between marriage readiness and identity status with sex.

1 INTRODUCTION

The process of individual development in the

adult period as a whole emphasizes the formation of

identity status and performs a new social role, one of

which is the ability and readiness in establishing a

stable intimate relationship or marriage readiness.

These two criteria are known as factors that determine

the individual in achieving psychological maturity in

the early adulthood (Erikson, 1968, Arnett, 2004;

Padilla-Walker et al., 2012). Building an intimate and

stable bond with others to have a child is one of the

major developmental tasks of early adulthood (Rauer

et al., 2013). Individual readiness to engage in bonds

is influenced by the process of identity formation,

because bonding requires an image of the identity of

a strong self, and a coherent identity within the self

makes individuals ready for gaining and maintaining

interpersonal commitment (Erikson, 1968;

Adamczyk and Luyckx, 2015). Previous studies have

proven the role of identity, identity formation process

towards individual initiation in achieving

housekeeping commitment (Arnett, 2004; Zimmer-

Gembeck and Petherick, 2006).

Marcia (1966) defines identity as 'the internal self-

structure which includes self-built constructs, the

organization of dynamic impulses, abilities, beliefs,

and individual life history'. Constitution of identity is

a development towards a steady individuality or can

be called a restructuring process. This self-

reconstructive process is assumed to strengthen the

process of the individual ego so as to be able to deal

with the various tasks of greater development. This

process links all previous identification and self-

image, in which earlier identity citations are

processed in future perspectives to deal with. The

establishment of identity as a fundamental

developmental task in the transition to adulthood

requires exploration of different alternatives in life

before the individual is committed to the chosen

device he sets (Adamczyk and Luyckx, 2015).

Exploration shows several periods experienced

individuals to think again, choose, and try various

roles and life plans that will be lived. The exploration

period is the time when the individual actively

chooses various meaningful alternative alternatives.

This is done by searching and exploring information

or alternatives as much as possible to compare. From

the results of comparison, the individual chooses or

makes a commitment to which alternative is most

profitable for himself in the future. Creation of

commitments is the level at which individuals make

choices about important issues of identity. When

commitment is made, the individual can be said to

have evaluated and proved that his choice is

congruent to his standards, expectations, and abilities.

Identification with commitment is an important

component in which individuals are confident and

386

Misbach, I., Rahman, S. and Damaianti, L.

Does Identity Status Influence Marriage Readiness Among Early Adults in Bandung City?.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences (ICES 2017) - Volume 1, pages 386-391

ISBN: 978-989-758-314-8

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

internalize the decisions that have been made

(Marcia, 1993; Adamczyk and Luyckx, 2015).

In the process, individuals will begin without

awareness of a clear identity (moratorium-no

exploration and commitment). As long as the

individual goes through the process of maturity, the

social demands create or force the state of the crisis

to ultimately make choices concerning survival, one

of which is marital issues. The crisis sometimes

generates a period of exploration of alternatives

identity (moratorium-the existence of uncommitted

exploration), after which it is expected to be able to

determine the choice of life as well as further solidify

the chosen identity (achievement-exploration

followed by commitment). However, there are

individuals who do not go through the exploration

process, where they tend to internalize expectations

of authority figures or social demands and norms in

their respective cultures, adopt goals, roles, and

beliefs about the modeled world without searching

and self-determination (foreclosure-a commitment

without exploration) (Marcia, 1993; Berman et al.,

2011).

The high level of exploration and commitment

indicates an increasingly mature or mature individual

identity, the more mature the identity is associated

with the high level of intimacy and individual

readiness in establishing a firm commitment with

others (Tesch and Whitbourne, 1982; Adamczyk and

Luyckx, 2015). When adults explore and then commit

to possibilities in every area of identity, they gain

awareness not just about who they are but focus on

their future role assignments. In other words, the

process in adulthood involves the adjustment of a new

social role into its identity (Crocetti et al., 2012;

Shulman and Connolly, 2013).

The present study was designed to identify the

entire identity dimensions which playing a role in the

marriage readiness of emerging adults. Previous

research has explored a number of issues in identity

development and relationship beliefs and formation,

but there are almost no finding research to date has

include the whole dimensions of identity

development and marriage readiness, it is found that

much of those research has explored only specific

dimensions such as achievement and variables such

as intimacy, attachment, premarital, short-term

beliefs and concurrent behaviors (Adamczyk and

Luyckx, 2015; Årseth et al., 2009; Askham, 1984;

Beyers and Seiffge-Krenke, 2010; Brzezińska and

Piotrowski, 2010). Most of the previous research also

conducted the study in Western cultures, which

makes the present study investigate how the culture

differences especially in East culture influenced the

identity formation and marriage readiness of

emerging adults.

2 METHODS

Participants in this study amounted to 118

respondents, who were early adults aged 21-45 years

(average age = 23.4 years), unmarried, and domiciled

in Bandung. 76% percent of the sample are female.

Researcher use non-probability sampling that is

purposive sampling, it involves selecting candidates

across a broad spectrum relating to the topic of study,

the idea is to focus on the precise similarity and how

it relates to the topic being researched thereby

achieving a greater understanding, thus, the sample is

selected to include people of interest and exclude

those who do not suit the purpose (Etikan et al,,

2016).

The instruments used to measure identity status

are Ego Identity Process Questionnaire (EIPQ)

proposed by Balistreri et al. (1995) to identify the

identity status of respondents. This scale consists of 2

sub-scales of commitment and exploration, which

consists of 32 statement items with 6 choices of

answer categories. Cronbach's α internal reliability

for the commitment dimension is 0.80 and for

exploration dimensions of 0.86 with test-retest

reliability of 0.90 for commitment dimensions and

0.86 for exploration dimensions (Balistreri et al.,

1995). In this research Cronbach's internal reliability

for the dimension of commitment of 0.76 while for

the exploration dimension of 0.57.

The instrument used to measure marriage

readiness is Personal Readiness Scale (PREP-M)

proposed by Holman, Busby, and Larson (1989) is a

measurement scale that measures the dimensions of

emotional health, emotional maturity, empathic

communication behavior, open communication

behavior, self- disclosure communication behavior,

self-esteem, drug abstinence, independence from

family of origin, overall readiness for marriage, age,

and religious activity. This scale consists of 36

statement items with 5 choices of answer categories.

Cronbach's α internal reliability of this instrument is

.86, whereas in this study is .75This research uses

correlation analysis of Multiple Regression and

Spearman correlation.

Does Identity Status Influence Marriage Readiness Among Early Adults in Bandung City?

387

3 RESULTS

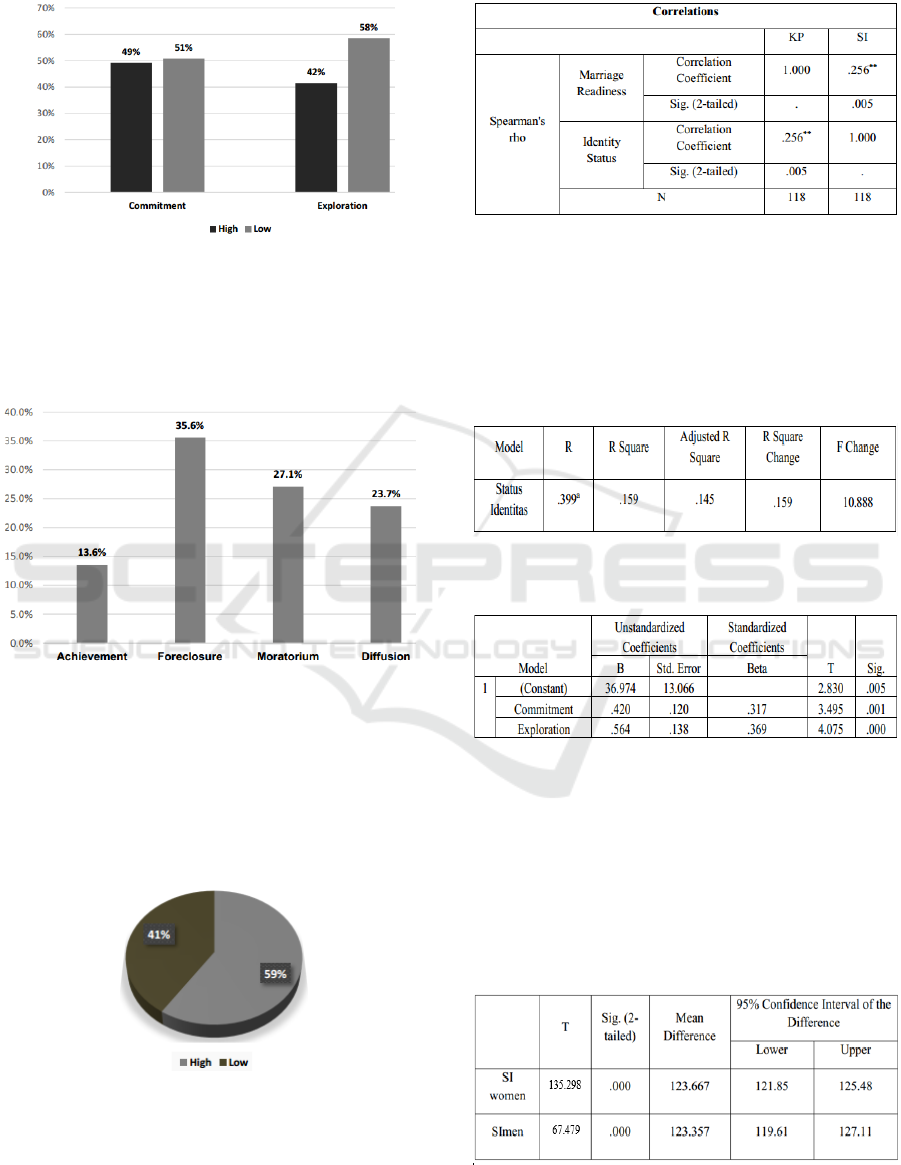

Figure 1: Identity status frequency.

Based on figure 1, then obtained data that

frequency of commitment most is in low category

with percentage equal to 51%, so also with frequency

of exploration aspect mostly in low category with

percentage equal to 58%.

Figure 2: Identity status frequency.

The figure 2 shows the frequency of the

proportion of each type of status on the identity of the

respondent, which found that the most dominant or

most of the respondents are of high priority

foreclosure identity 35.6%, followed by the identity

of the moratorium (27.1%), diffusion (23.7%), and

achievement (13.6%).

Figure 3: Frequency of marriage readiness.

Based on figure 3, the data obtained that the

frequency of most marriage readiness is on the high

category with a percentage of 59%.

Table 1: Correlation of Identity Status to Marriage

Preparation.

Spearman's correlation coefficient in table 1

shows a significant relationship between the status of

identity and the preparedness of marriage (r = .256, p

<.05), the results indicate that the more mature

individual identity is associated with the readiness of

marriage in early adulthood.

Table 2: Influence of identity status on marriage readiness.

Table 3. Influence coefficients identity status and

exploration commitment to marriage readiness.

The results in table 2 and 3 showed that

individuals who engage in exploration (β = 0:42, p

<.05) and a commitment (β = 0:56, p <.001) also have

the readiness to marry with a correlation coefficient

(r = 0388) and the determinant coefficient of

readiness describe marriage can have described by the

identity status of 15.9% (R ² = .159).

Table 4. Comparison of status of identity of men and

women.

ICES 2017 - 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences

388

There is a difference in table 4 between the status

of male identity and status of women's identity. Score

identity status of women (t = 135 298, p <.001) were

significantly higher than men (t = 67 479, p <.001).

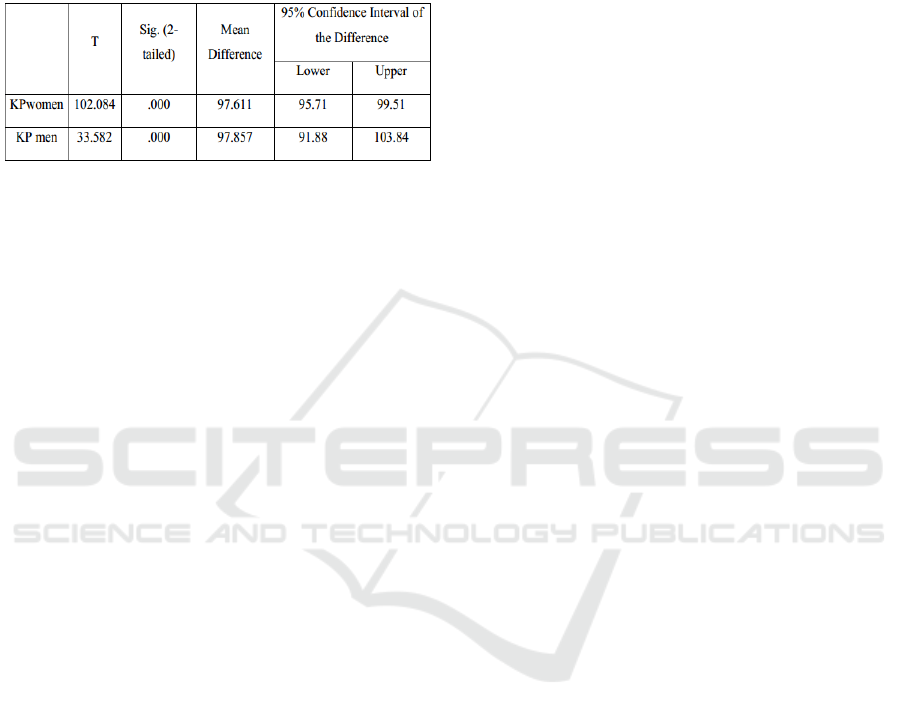

Table 5. Comparison of marriage preparation in men and

women.

There is a difference in table 5 between male

marriage readiness and female identity status.

Woman marriage readiness score (t = 102 084, p

<.001) were significantly higher than men (t = 33 582,

p <.001).

4 DISCUSSION

The findings in this study indicate that there is a

significant influence between the aspects of

exploration and commitment to marriage readiness.

The frequency of proportion of foreclosure identity

status and high marriage readiness in this study can

be attributed to the high percentage of female

respondents compared to men, which is in accordance

with previous research results which proves that

women in the early adult period tend to focus on

matters of relation intimate interpersonal or marriage

as well as more family oriented than men. In the early

adulthood to middle adulthood, their openness to the

exploration process appears to have decreased, and

increased in the commitment process so it is said that

this period is characterized by an increase in the

foreclosed intimate relationship identity or foreclosed

identity as a whole (Cramer, 2000; Cramer 2004;

Arnett, 2004; Kroger, 2007; Fadjukoff et al., 2007).

From the results of comparison in this study also

known that the female marriage readiness score is

higher than men, this is because men in the early adult

period tend not to think about marriage as well as

receive less pressure to marry compared with women.

Consistently, women are found to have shorter

waiting periods to get married and better prepared to

step into marriage than men, due to cultural demands

or expectations especially in Indonesia that are more

influential and focusing on women to think more

about marriage than men (Whitehead and Popenoe,

2000; Larson et al., 1998; Oppenheimer, 1988).

Erikson (1968) states that men tend to solve the

problem of some conflicts in identity earlier than

women, but not in the domain of sexual ideology. The

urge for women to think about marriage earlier is due

to a tendency for eligible men as life companions to

reject older women, so the likelihood of competition

among women occurs significantly. This is also

consistent with the ideal age trend for marriage for

women today, at the age of 27 (Whitehead and

Popenoe, 2000, 2004; Larson et al., 1998;

Oppenheimer, 1988).

Individuals in early adulthood are expected to

carry out a new social role where one of the main ones

is their readiness in carrying out marriage

responsibilities. Individuals with strong identity

awareness provide a strong basis for the development

of a mature social role, in which the capacity to

commit without fear of losing his ego (Erikson, 1968;

Beyers and Seiffge-Krenke, 2010). In societies with

high collectively cultures, like Indonesia, individuals

tend to have an interdependent self-construct. In

individuals with Eastern or Asian cultures, more are

found with foreclosure or diffusion identities than

Western cultures, so they are considered to have an

identity status which is considered less mature (less

mature). Exploration represents individuality, a self-

directed approach to developing self-awareness, in

which the approach may be incompatible with the

collectivist and interdependent Asian cultural

context. It is possible that the identity of the Asian

community does not so much pass through processes

that require crisis, exploration, self-discovery, and

commitment, but tend to be more collectively

accepted, which makes the level of commitment and

distress lower than in Western culture. In a communal

Asian culture, the development and awareness of

identity adopt a collective identity that is influenced

by members of the immediate group such as family,

friends, or community environment itself. It is also

said that fulfilling a social role in adulthood does not

necessarily indicate that the individual has maturity

or identity maturity, and does not always lead to

psychological independence. In other studies, it is

mentioned that the social role that is fulfilled in

adulthood is more associated to the age of the

individual than the identity or psychological maturity,

which also states that the responsibility for a

particular role is determined by social norms that

determine the ideal age to take on the role. This has

led to limited exploration that can be done by

individuals (Piotrowski et al., 2013; Yeh and Huang

1996; Markus and Kitayama, 2003; Berman et al.,

2011).

Does Identity Status Influence Marriage Readiness Among Early Adults in Bandung City?

389

5 CONCLUSION

This study proves that the development of identity

plays an important role in the transition to adulthood.

Specifically, the formation of identity is connected to

the readiness of each individual to assume a new

social role in entering the marriage stage. In addition,

it is important to know the identity of what is formed

when entering adulthood. In terms of marital

readiness, it can be stated that horizontal marriages

could not be considered equal in all adult individuals,

and differences in processes and objectives must be

ignored. While most important, this study reveals the

effect of identity formation on individual wedding

preparedness, which helps understand the

implications of various belief variables about

marriage, how the development that occurs during the

adult stage paves the way for success in every role in

adulthood. It provides important knowledge in

understanding how early adulthood individuals

perceive their role in marriage and in understanding

how individual readiness forms in marriage during

the transition to adulthood.

REFERENCES

Adamczyk, K., Luyckx, K., 2015. An Investigation of the

Linkage between Relationship Status (Single vs.

Partnered), Identity Dimensions and Self-construals in

a Sample of Polish Young Adults. Polish Psychological

Bulletin. 46(4), 616–623.

Arnett, J. J., 2004. Emerging adulthood: The winding

roadfrom the late teens through the twenties, Oxford

University Press. New York.

Årseth, A. K., Kroger, J., Martinussen, M., Marcia, J. E.,

2009. Meta-Analytic Studies of Identity Status and the

Relational Issues of Attachment and Intimacy. Identity:

An International Journal of Theory and Research. 9, 1–

32.

Askham, J., 1984. Identity and stability in marriage,

Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Balistreri, E., Busch-Rossnagel, N. A., Geisinger, K. F.,

1995. Development and preliminary validation of the

Ego Identity Process Questionnaire. Journal of

adolescence. 18(2), 179-192.

Beyers, W., Seiffge-Krenke, I., 2010. Does Identity Precede

Intimacy? Testing Erikson’s Theory on Romantic

Development in Emerging Adults of the 21

st

Century.

Journal of Adolescent Research. 25(3), 387 –415.

Berman, S. L., Yu-Fang, Y., Seth, S., Grace, T., Kohei M.,

2011. Identity Exploration, Commitment, and Distress:

A Cross National Investigation in China, Taiwan,

Japan, and the United States. Child Youth Care Forum.

40, 65–75.

Brzezińska, A. I., Piotrowski, K., 2010. Formowanie

siętożsamości a poczucie dorosłości, gotowośćdo

bliskich związków i poczucie koherencji [Identity

formation, sense of being adult, readiness to intimate

relationships and sense of coherence]. Czasopismo

Psychologiczne. 16(2), 265–274.

Cramer, P., 2000) Development of identity: Gender makes

a difference. Journal of Research in Personality. 34(1),

42-72.

Cramer, P., 2004. Identity change in adulthood: The

contribution of defense mechanisms and life

experiences. Journal of Research in Personality. 38(3),

280-316.

Crocetti, E., Scrignaro, M., Sica, L., Magrin, M., 2012.

Correlates of identity configurations: Three studies

with adolescent and emerging adult cohorts. Journal of

Youth and Adolescence. 41(6), 732–748.

Erikson, E. H., 1968. Youth and Crisis, WW Norton &

Company. New York.

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., Alkassim, R. S., 2016. Comparison

of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling.

American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics.

5(1), 1-4.

Fadjukoff, P., Kokko, K., Pulkkinen, L., 2007. Implications

of timing of entering adulthood for identity

achievement. Journal of Adolescent Research. 22, 504-

530.

Holman, T. B., Busby, D. M., Larson, J. H., 1989.

PREParation for marriage (PREP-M). Marriage Study

Consortium. Provo, UT.

Kroger, J., 2007. Identity development: Adolescence

through adulthood, Sage. Thousand Oaks.

Larson, J. H., Benson, M. J., Wilson, S. M., Medora, N.,

1998. Family of origin influences on marital attitudes

and readiness for marriage in late adolescents. Journal

of Family Issues. 19(6), 750-768.

Marcia, J. E., 1993. The ego identity status approach to ego

identity, Springer. New York.

Markus, H. R., Kitayama, S., 2003. Culture, self, and the

reality of the social. Psychological inquiry. 14(3-4),

277-283.

Oppenheimer, V. K., 1988. A theory of marriage timing.

American journal of sociology. 94(3), 563-591.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Larry, J. N., Jason, S. C., 2012.

Affording Emerging Adulthood: Parental Financial

Assistance of their College-Aged Children. J. Adult

Dev. 19(1), 50-58.

Piotrowski, K., Brzezińska, A. I., Pietrzak, J., 2013. Four

statuses of adulthood: adult roles, psychosocial

maturity and identity formation in emerging adulthood.

Health Psychology Report. 1, 52-62.

Popenoe, D., Whitehead, B. D., 2004. The state of our

unions, National Marriage Project, Rutgers.

Rauer, A. J., Pettit, G. S., Lansford, J. E., Bates, J. E.,

Dodge, K. A., 2013. Romantic relationship patterns in

young adulthood and their developmental antecedents.

Developmental Psychology. 49(11), 2159.

Shulman, S., Connolly, J., 2013. The challenge of romantic

relationships in emerging adulthood:

ICES 2017 - 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences

390

Reconceptualization of the field. Emerging Adulthood.

1(1), 27–39.

Tesch, S. A., Whitbourne, S. K. 1982. Intimacy and identity

status in young adults. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology. 43(5), 1041–1051.

Whitehead, B. D., Popenoe, D., 2000. Sex without strings,

relationships without rings. The state of our unions,

2000: The social health of marriage in America. 6-20.

Yeh, C. J., Huang, K., 1996. The collectivistic nature of

ethnic identity development among Asian-American

college students. Adolescence. 31(123), 645-662.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Petherick, J., 2006. Attachment

patterns during Year 12: Psychological symptoms,

rejection sensitivity, loneliness, social competence, and

support as correlates of stability and change. The

Educational and Developmental Psychologist. 23(2),

65-86.

Does Identity Status Influence Marriage Readiness Among Early Adults in Bandung City?

391