Household Income and Unbalanced Diet Among Urban Adolescent

Girls

Rian Diana, Sri Sumarmi, Triska Susila Nindya, Mahmud Aditya Rifqi, Stefania Widya

Setyaningtyas and Emalia Rhitmayanti

Department of Nutrition, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga, Mulyorejo, Surabaya, Indonesia

rian.diana@fkm.unair.ac.id

Keywords: Adolescent girls, Dietary intake, Income, Urban.

Abstract: Dietary intakes are important for adolescent girls’ growth and development. Not all adolescents have an

adequate daily intake, particularly in urban areas which have a high disparity of household income. This

study was aimed to examine the relationship between household income and dietary intakes among

adolescent girls in urban areas. This cross-sectional study included 132 subjects aged 12-16 years old,

conducted in Junior high school in Surabaya City, East Java, Indonesia. Dietary intakes were obtained by

using 24-hour dietary recall method. Spearman’s rank correlation was applied to analyse the association

between household income and dietary intakes. High disparity of household income was found in this study

with median IDR 4,000,000 (≈$308). Adolescent girls had low dietary intakes with median as follows,

energy 1235kcal, protein 45.1g, fat 46.1g, carbohydrate 141.6g, iron 5.0mg, calcium 182.8mg. The

proportion of energy from carbohydrate was 49.5%, fat 34.9% and protein 14.8%. There was a significant

correlation between household income with protein intake (p=0.010, r=0.224) and energy proportion from

protein (p=0.043, r=0.177). Generally, adolescent girls eat an unbalanced diet, with less carbohydrate and

high fat. Urban adolescent girls with low household income have a low protein intake.

1 INTRODUCTION

Dietary intakes are important for adolescent girls’

growth and development. Adolescence is a crucial

time for puberty and body image development.

Negative body image, which includes body

dissatisfaction, is a strong predictor of disordered

eating behaviours. Bad eating behaviour can lead to

malnutrition (Reel et al, 2015). Not all adolescents

have an adequate intake (Badan Penelitian dan

Pengembangan Kesehatan, 2014). Poor intake can

lead to malnutrition (Branca et al, 2015), delay in or

faster sexual maturation (Soliman et al, 2014), and

not reaching optimal catch up growth (Modan-

Moses et al, 2012). Adolescent eating behaviour is

influenced by personal factors, physical, social

environment (Salvy et al, 2012) and socioeconomic

factors (El-Gilany and Elkhawaga, 2012).

There have been many studies about dietary intake

and its determinants among female adolescents (de

Andrade et al, 2016), including association between

socioeconomics and diet quality (Darmon and

Drewnowski, 2008). Few studies have been

conducted on dietary intake and its correlation with

household income in Surabaya City with high

income disparity. The purpose of this study was to

examine the relationship between household income

and dietary intakes among adolescent girls in urban

area.

2 METHODS

This cross-sectional study included 132 subjects

aged 12-16 years old, conducted in Santa Agnes and

Unggulan Bina Insani junior high school in

Surabaya City, East Java, Indonesia. The two school

represent the diversity of household socio-economic

in urban area (low-high income household). Dietary

intakes were obtained by using 24-hour dietary

recall method. Energy and nutrient intakes were

calculated by Nutrisurvey (2007). Descriptive

analysis was determined by median, minimum,

maximum and proportion. Energy proportion from

carbohydrate, fat and protein were categorised into

Diana, R., Sumarmi, S., Nindya, T., Rifqi, M., Setyaningtyas, S. and Rhitmayanti, E.

Household Income and Unbalanced Diet Among Urban Adolescent Girls.

In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association (INAHEA 2017), pages 295-297

ISBN: 978-989-758-335-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

295

two groups (carbohydrate: <55% energy and ≥ 55%

energy; fat: < 30% energy and ≥ 30% energy;

protein: < 15% energy and ≥ 15% energy)

(Hardinsyah et al, 2014). Spearman’s rank

correlation was applied to analyse the correlation

between household income and dietary intakes and p

value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

High disparity of household income and dietary

intake was found in this study. Household income

median was IDR 4,000,000 per month (1 USD =

around IDR 13,000). The lowest household income

was IDR 500,000 ((≈$38) and the highest was IDR

50,000,000 ((≈$3846) per month. Table 1 shows that

dietary intake of adolescent girls in urban areas was

below the adequacy level. Adolescent girls had low

dietary intakes with median as follows: energy

1235kcal, protein 45.1g, fat 46.1g, carbohydrate

141.6g, iron 5.0mg and calcium 182.8mg. High

disparity in dietary intake can be seen from the

lowest intake and the highest intake.

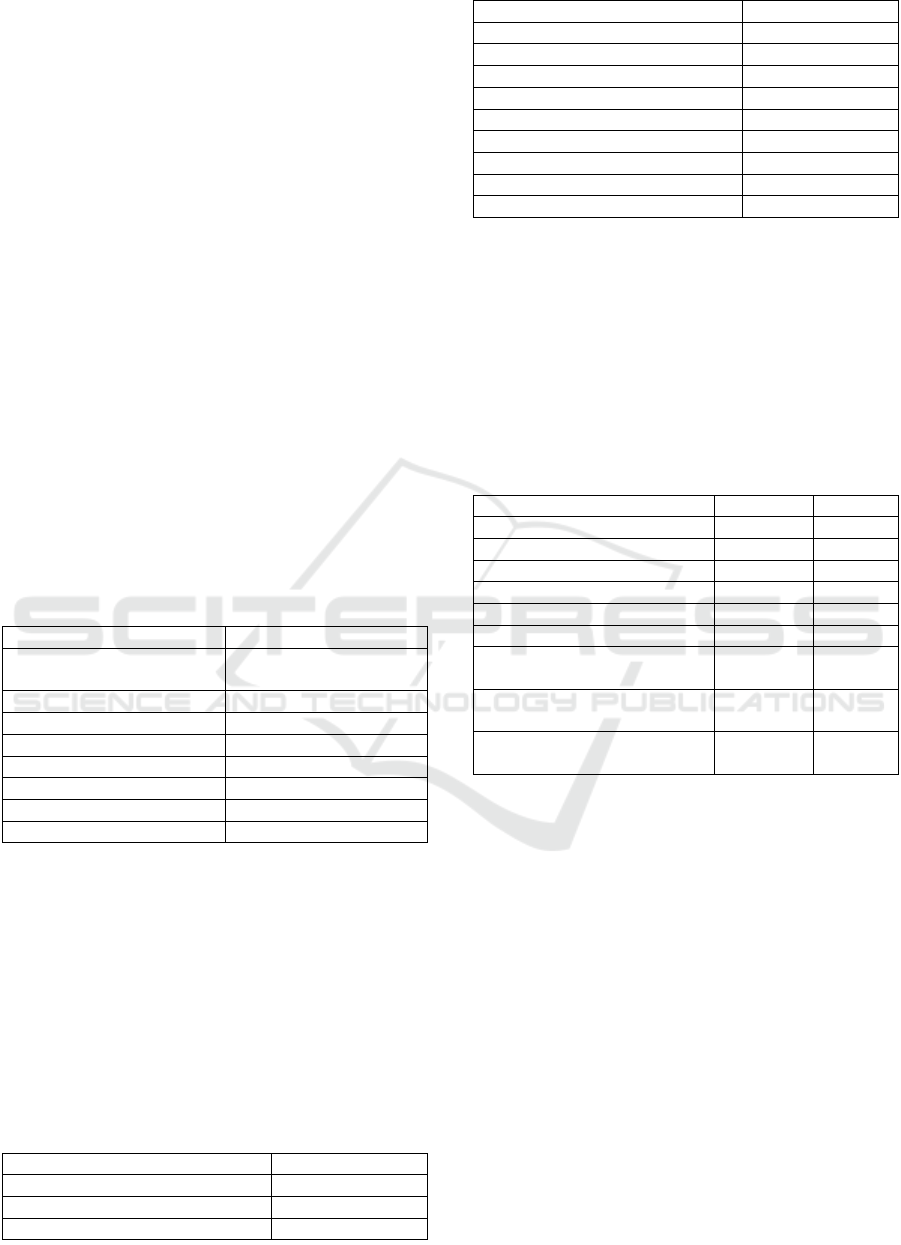

Table 1: Median of household income and dietary intake

Variable

Median (min; max)

Household income

(IDR/month)

4,000,000

(500,000; 50,000,000)

Dietary intake

Energy (kcal)

1235 (374; 4027)

Protein (g)

45.1 (8.8; 171.5)

Fat (g)

46.1 (4.2; 185.1)

Carbohydrate (g)

141.6 (24.9; 821.0)

Iron (mg)

5 (0.8; 71.0)

Calcium (mg)

182.8 (25.6; 1886.8)

Based on the proportion of energy from

carbohydrate, fat and protein, adolescent girls have

an unbalanced diet. Table 2 shows that energy

proportion from carbohydrate was 49.5%, fat 34.9%

and protein 14.8%. More than half of adolescent

girls have a low energy proportion from

carbohydrate and protein, contrarily with energy

proportion from fat. Generally, adolescent girls eat

an unbalanced diet with less carbohydrate, protein

and high fat.

Table 2: Energy proportion

Energy Proportion (%)

n (%)

Carbohydrate

< 55% energy

85 (64.4)

≥ 55% energy

47 (35.6)

Median (min; max)

49.5 (10.9; 90.5)

Fat

< 30% energy

48 (36.4)

≥ 30% energy

84 (63.6)

Median (min; max)

34.9 (4.5; 70.9)

Energy Proportion (%)

n (%)

Protein

< 15% energy

69 (52.3)

≥ 15% energy

63 (47.7)

Median (min; max)

14.8 (2.7; 28.5)

Correlation between variables in this study can

be seen in Table 3. Protein intake (p=0.010, r=0.224)

and energy proportion from protein (p=0.043,

r=0.177) have a positive correlation with household

income. There was no significant correlation for

energy, fat, carbohydrate, iron and calcium with

household income.

Table 3: Correlation between dietary intake, energy

proportion and household income

Variable

r

p

Intake of energy (kcal)

0.083

0.346

Intake of fat (g)

0.054

0.535

Intake of protein (g)

0.224

0.010

Intake of carbohydrate (g)

0.054

0.535

Intake of iron (mg)

0.159

0.069

Intake of calcium (mg)

0.025

0.780

Energy proportion from

carbohydrate (%)

-0.043

0.627

Energy proportion from fat

(%)

-0.009

0.920

Energy proportion from

protein (%)

0.177

0.043

4 DISCUSSION

Household income of adolescent girls are very

diverse, from IDR 500,000-50,000,000. This high

disparity income can lead to high differences of food

access. The median of adolescent household income

was higher than Surabaya minimum wages (IDR

3.296.212). Higher incomes enhanced the

sustainability of food access (Adom, 2014).

Table 1 shows that adolescent nutrient intake

was below the recommended dietary allowance

(RDA). RDA for adolescent girls was: energy

2125kcal, protein 69g, fat 72g, carbohydrate 292g,

iron 26g and calcium 1200mg. Low nutrient intake

can cause suboptimal growth (Alshammari et al,

2017) and development (Solimin et al, 2014).

Unbalanced diet among adolescent girls is found

in this study with a high energy proportion from fat

INAHEA 2017 - 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association

296

(>30%) and low energy proportion from

carbohydrate (<55%) and protein (<15%).

Adolescents eat a lot of fried food, so they have a

high energy proportion from fat. Table 3 shows that

there was a significant association between protein

intake and energy proportion from protein with

household income. This implies that parents with

higher incomes can fulfil their children's protein

intake better than those of low incomes. Animal

sources of protein have a better quality than non-

animal protein. But, animal protein prices are more

costly than non-animal. Muzayyanah et al. (2017)

revealed that increase in household income can

improve the animal protein consumption. Darmon

and Drewnowski (2008) in their review stated that

socioeconomic status can influence diet quality and

diet cost. People with lower socioeconomic status

have a lower diet quality than higher ones. There

was no significant association between other nutrient

intake with household income. This may be because

a result of the homogeneous data of nutrient intake.

Limitation of this study was dietary intake

collected using 24-hour recall. This method has

recall bias and is not representative for micronutrient

intake. The trained enumerator questioned and

probed to reduce the recall bias and food picture

were used to visualise the portion size.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Adolescent girls in urban area eat an unbalanced

diet, with high fat and less carbohydrate. Urban

adolescent girls with low household income have a

low protein intake.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thanks to Faculty of Public Health, Universitas

Airlangga for funding this study.

REFERENCES

Adom, P.K. (2014). Determinants of food

availability and access in Ghana: what can we

learn beyond the regression results ? Stud Agric

Econ 116(3):153–64. [online] Available at:

http://econpapers.repec.org/article/agsstagec/196

909.htm (Accessed: ).

Alshammari, E., Suneetha, E., Adnan, M., Khan, S.

and Alazzeh, A. (2017). Growth Profile and Its

Association with Nutrient Intake and Dietary

Patterns among Children and Adolescents in Hail

Region of Saudi Arabia.1–9.

Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan.

(2014), Buku Studi Diet Total: Survei Konsumsi

Makanan Individu Indonesia 2014. Jakarta:

Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan,

Kementerian Kesehatan RI.

Branca, F., Piwoz, E., Schultink, W. and Sullivan,

L.M. (2015). Nutrition and health in women,

children, and adolescent girls. BMJ, 351h4173.

Darmon, N. andDrewnowski, A. (2008). Does social

class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 87(5),

pp. 1107–17.

de Andrade, S.C., Previdelli, Á.N., Cesar, C.L.G.,

Marchioni, D.M.L. and Fisberg, R.M. (2016).

Trends in diet quality among adolescents, adults

and older adults: A population-based study. Prev

Med Reports, 4, pp.391–396.

El-Gilany, A.H. and Elkhawaga, G. (2012).

Socioeconomic determinants of eating pattern of

adolescent students in Mansoura, Egypt. Pan Afr

Med J.,13, p. 22.

Hardinsyah, H. Riyadi, H. and Tambunan, V.

(2014). Energy, Protein, Fat, and Carbohydrate

Adequacy (Kecukupan Energi, Protein, Lemak,

dan Karbohidrat). In: Recommended Dietary

Allowance Indonesia (Angka Kecukupan Gizi

yang Dianjurkan Bagi Bangsa Indonesia).

Jakarta: Ministry of Health Indonesia, pp. 26–47.

Modan-Moses, D., Yaroslavsky, A., Kochavi, B.,

Toledano, A., Segev, S., Balawi, F., Mitrany, E.

and Stein, D. (2012). Linear Growth and Final

Height Characteristics in Adolescent Females

with Anorexia Nervosa. PLoS One. 7(9), e45504.

Muzayyanah, M.A.U., Nurtini, S., Widiati, R.,

Syahlani, S.P. and Kusumastuti, T.A. (2017).

Household Decision Analysis on Animal Protein

Food Consumption: Evidence From D.I

Yogyakarta Province. Bul Peternak, 41(2),

pp.203–211.

Reel, J., Voelker, D. and Greenleaf, C. (2015).

Weight status and body image perceptions in

adolescents: current perspectives. Adolesc Health

Med Ther.,6, pp.149–158.

Salvy, S., de Haye, K., Bowker, J.C. and Hermans,

R.C.J. (2012). Influence of Peers and Friends

on Children’s and Adolescents’ Eating and

Activity Behaviors. Physiol Behav.,106(3), pp.

369–378.

Soliman, A., De Sanctis, V. and Elalaily, R. (2014).

Nutrition and pubertal development. Indian J

Endocrinol Metab., 18(1), S39-47.

Household Income and Unbalanced Diet Among Urban Adolescent Girls

297