User Centered Design of an Augmented Reality Gaming Platform for

Active Aging in Elderly Institutions

Hugo Simão and Alexandre Bernardino

Institute for Systems and Robotics, Instituto Superior Técnico, University of Lisbon, Portugal

Keywords: Active Ageing, Human Centred Design, Augmented Reality, Exergames.

Abstract: In this article, we describe the design and development of a gaming platform with augmented reality

components whose purpose is to fight sedentary lifestyle by promoting active aging in elderly institutions.

The augmented reality components project games on the floor where the users can interact by moving

sideways or sitting and playing with the arms. In this work, we target the design of a complete platform that

can be easily transported, configured and deployed in elderly institutions to promote exercise. The concepts

were developed using a user-centered methodology. End-users were motivated to participate in a study where

social, economic and pathological conditions were analysed. The acceptance of the concept, the expectations

generated, and the concerns raised, were assessed through questionnaires formulated both to the elderly users

and to the professionals of the care institutions. Our results show that the elderly can be stimulated to practice

physical exercise with the addition of fun and social interaction.

1 INTRODUCTION

Modern societies have a growing elderly population

due to the medical advances that increase the life

expectancy of the human being. In developed

countries, there is also social pressure to maintain the

quality of life and optimize the institutions that care

for the elderly. This growing number of people can

benefit from digital technology innovation tailored to

different needs. The aging population represents one

of the major societal problems today with a rising

trend (Nations, 2015). All people born in the

Babyboom era will belong to the elderly population

(Allianz, 2014) in less than a decade and a half,

representing 1.4 billion people by 2030 (Nations,

2015). The fight against sedentarism and the

promotion of active aging are a necessity to provide a

better quality of life and to combat the problems of

the geriatric population (Udayshankar &

Parameaswari, 2014). This aging population will

require infrastructures, professionals and tools

adapted and optimized to respond to the challenges

associated to the elderly age. The existing

infrastructures are insufficient to provide services to

all elderly (Bloom, Jimenez, & Rosenberg, 2011).

Traditional services are sometimes less agile and less

versatile in the response provided. For example,

activities carried out by occupational therapists are

run using mainly paper and pencil, often in group

activities. However, new technologies provide a

much wider range of possibilities to promote active

lifestyles that urge to be exploited by the society and

professionals. Furthermore, many of the institutions

targeted in this work have a short number of

professionals that is clearly insufficient to provide

adequate support in periodic examinations and

revaluations of the physical and cognitive conditions

for all. These facts portray the need to use

technological approaches that allow an optimization

of resources.

In this study, we describe the initial work in

designing and testing a digital interactive platform

that promotes physical exercise in the geriatric sector.

We used an iterative design process to build and user

test the platform to meet the needs, concerns, and

expectations listed by the professionals and elderly of

the institutions. Also, we want to understand how we

can create approaches focused on physical activity to

improve wellbeing in late life. In this way, for the

platform development, we use a process based on

user-centered-design (Abras, Maloney-Krichmar, &

Preece, 2004).The design process is composed of

three stages. The first stage only takes into account

the technological and logistic requisites of the system:

it must include the necessary hardware and software

SimÃ

ˇ

co H. and Bernardino A.

User Centered Design of an Augmented Reality Gaming Platform for Active Aging in Elderly Institutions.

DOI: 10.5220/0006606601510162

In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support (icSPORTS 2017), pages 151-162

ISBN: 978-989-758-269-1

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

for operating a pre-defined set of games for exercise

and it must be easily transported between and within

the care institutions. A prototype was developed for

early testing. In the second stage the developed

prototype was presented at three care institutions and

a series of interviews allowed the collection of

feedback both from professionals and elderly users.

The interview generated a set of guidelines to

improve the design. In particular the need for suitable

covers and interfaces was pointed out by the

interviewees.

In the third stage, we designed alternative concepts

for the cover and interfaces that were again presented

to the institutions. A final design was selected for

production.

This paper starts with an overview of related work

in Section 2, where the main approaches for

technological devices for the promotion of exercise

among the elderly are outlined. In section 3, 4 and 5

we describe the three aforementioned stages of

design. In Section 6 we discuss the main concerns and

expectations that we could infer from the interviews

with the professionals and users. Finally, in Section 7

we draw the main conclusions of the study and

perspectives for future developments.

2 RELATED WORK

The work on this article tries to address the lack of

technological tools in geriatric institutions in

Portuguese context, to promote active aging. It’s

specifically focused on the physical exercise

component allied to cognitive stimulation. Active

aging is seen as a primordial thing in society that

encourages an improvement in the general quality of

life (Mendoza-Ruvalcaba & Arias-Merino, 2015),

specifically in our study, the part of mobility

(Rantanen, 2013). However, sometimes the difficulty

is in eliciting users to opt for a more dynamic and less

sedentary lifestyle. The reasons depart from society

(Rantanen, 2013), motivation issues in older people

(Francis, 2014) and some health professionals may

involuntary discourage older people from exercising

(Hirvensalo, Heikkinen, Lintunen, & Rantanen,

2005).

It has been observed in the literature that

traditional methods of activities, if recreated in a

different and stimulating way, guarantee higher levels

of interest and participation when compared to

conventional methods (Cohen, 2006). In particular,

exergames are video games that rely on technology to

promote an active lifestyle (Sinclair, Hingston, &

Masek, 2007) and represent a good alternative to

traditional methods, for potentiating physical

exercise, simultaneously promoting cognitive

stimulation and dialogue (Pasqualotti, Barone, &

Doll, 2012), (Gerling, et. al., 2014), (Mandryk &

Gerling, 2015). Exergames can also be a good

strategy for rehabilitation therapies, as expressed by

some authors (Alankus, et. al., 2014) (Gerling, et. al.,

2015). Additionally, using wearable technologies

allows monitoring of vital signs and efficient

continuous monitoring (Fletcher, Poh, & Eydgahi,

2010), although a search for less intrusive solutions is

currently searched (El-Bendary, Tan, Pivot, & Lam,

2013). Approaches such as those taken by (Maczka,

Parry, & Curry, 2015) measure the effects potentiated

by technology in responding to the needs of

institutions, which increase the effectiveness and

efficiency of professionals. These current approaches

use games as a resource, based on physical exercise

combined with cognitive stimulation, which can bring

health benefits to the elderly (Gonzalez et al., 2008),

(Omholt & Wærstad, 2013). There are also studies

that list some advantages of approaches based on

virtual reality (Ribeiro-Papa, Masseti, Crocetta,

Menezes, & Antunes, 2016), (García-Betances,

Jiminéz-Mixco, Arredondo, & Cabrera-Umpiérrez,

2014), and trough exergaming (Rice et al., 2011)

resulting in a reduction of disability and depression

(Skelton & Dinan-Young, 2008). Also, the game

consoles industry has been developing augmented

reality games for the past 15 years that complement

the virtual gameplay with physical interaction. This

field of entertainment stimulates group activities and

family interaction, while promoting physical exercise

(Nintendo, 2009), (Playstation, 2009). One limitation

of this kind of technology is that it mainly targets

children and young adults and in general, they were

designed for groups of people with full motion

capacity. There are also intergenerational approaches

in this sense as the Age Invaders (Khoo & Cheok,

2006) which has the added value of minimizing the

generational gap through games.

However, the aging population is is prone to to

have a sedentary lifestyle and the one that requires

more external help for encouragement for the practice

of physical exercise (Harvey, Chastin, & Skelton,

2013). In addition, because game consoles do not

spontaneously motivate the beneficiary to the action,

they rely on the user’s proactive behaviour, which is

more likely to happen in the young population.

Another problem worth of attention in the use of

games for elderly people is that they are often too

complex for this population (Mader, Dupire, Natkin,

& Guardiola, 2012). The problems highlighted are

related to game speed, too many visual elements and

lack of feedback (Omholt & Wærstad, 2013).

The importance of user-centered design has been

stressed in the literature by Omholt, Gulliksen and

Rice (Omholt & Wærstad, 2013), (Gulliksen, Lantz,

& Boivie, 1999), (Rice et al., 2011). The primary

objective of the user-centered design is to involve the

public for whom it is developing, generating

customized solutions adapted to them, in an iterative

process with periodic contact points (Baek, Cagiltay,

Boling, & Frick, 2008).

Following similar principles, in this project, we

developed a system that would stimulate a more

active response of the geriatric segment, in which we

included aspects suggested by the professionals and

elderly users in the design, but with added attention

to the requirements on miniaturization and

portability.

2.1 Main Contribution

In this work, we proposed an interactive platform for

games. This study is based on user centered design

regarding the platform design and user test in the pre-

defined context. Besides, some design guidelines

were established for the development of exergames

platforms. Our study provided a platform that

combines augmented reality through projections and

simultaneously measure vital signs and manage

parameters such as balance, posture, agility, and

aerobic activity.

3 DESIGN PROCESS - STAGE 1

The first stage of design relied on the technological

and logistic requirements of the platform. Previous to

this stage, the infrastructure necessary to experience

the games that we had at university could not be

transported easily because of its size.To test the

system with users in real contexts in multiple

institutions, there was a need to reduce the size of the

structure that projects the games, so that it could be

easily transported.

These logistical and size requirements dictated the

birth of the platform that is being developed under the

scientific project AHA (aha.isr.tecnico. ulisboa.pt).

This project aims to use a social robot for the

promotion of physical exercise in a geriatric context.

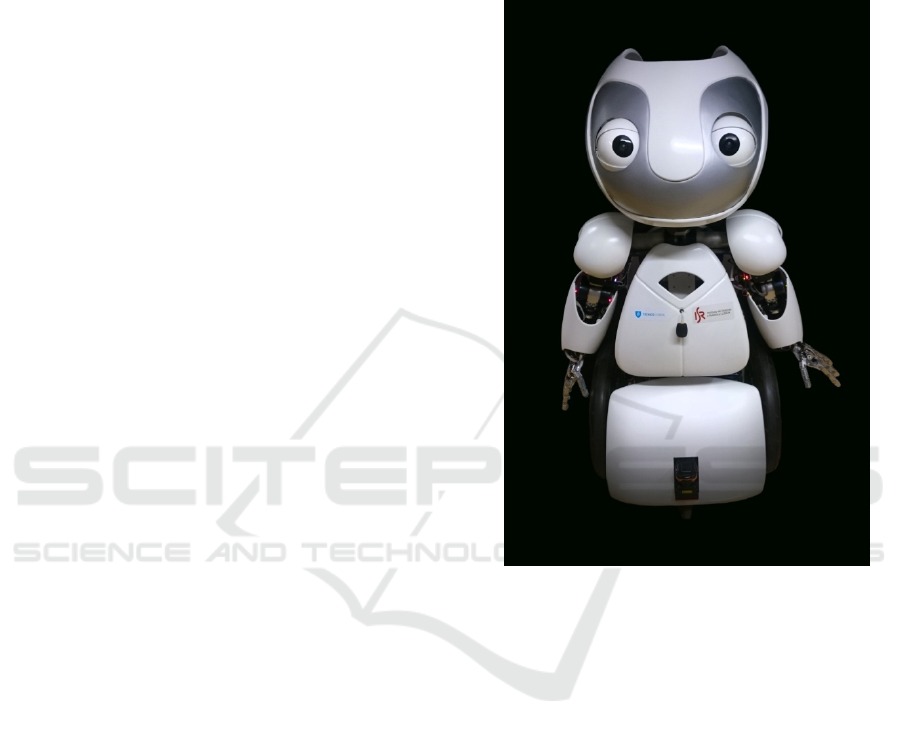

The robot in question, Vizzy (Moreno et al., 2016),

has two fundamental components:

autonomy/mobility and promotion of physical

exercise. Vizzy, shown in Fig. 1, will elicit people to

do physical activity through verbal instructions and

body language that users will have to imitate. Also,

Vizzy will play the role of mediator and dynamic

element of institution areas, in which he will control

the same games as the platform. At the same time,

Vizzy will monitor the performance of users playing

these games.

Figure 1: The social robot Vizzy to be used as the target of

AHA project.

In this paper, we focus on the execution of a

platform without the robotic components for more

easy validation of the augmented reality games, that

we denote Portable Exergame Platform for Elderly

(PEPE). PEPE will allow to evaluate and validate

some of the components that robot Vizzy might

incorporate, and be himself a provider of game

exercises to the elderly population. It may also be

used independently of Vizzy as a lower cost

standalone product that may share with Vizzy some

common aspects. In this sense, some technological

components were included in the interactive gaming

platform, to test its relevance and future applicability

in Vizzy. In this study, we fit PEPE into a play

product that simultaneously aggregates medical

component, prevention and maintenance of

functionalities. PEPE also has the purpose of studying

mechanisms and strategies of promotion and

motivation to physical exercise. This concept is

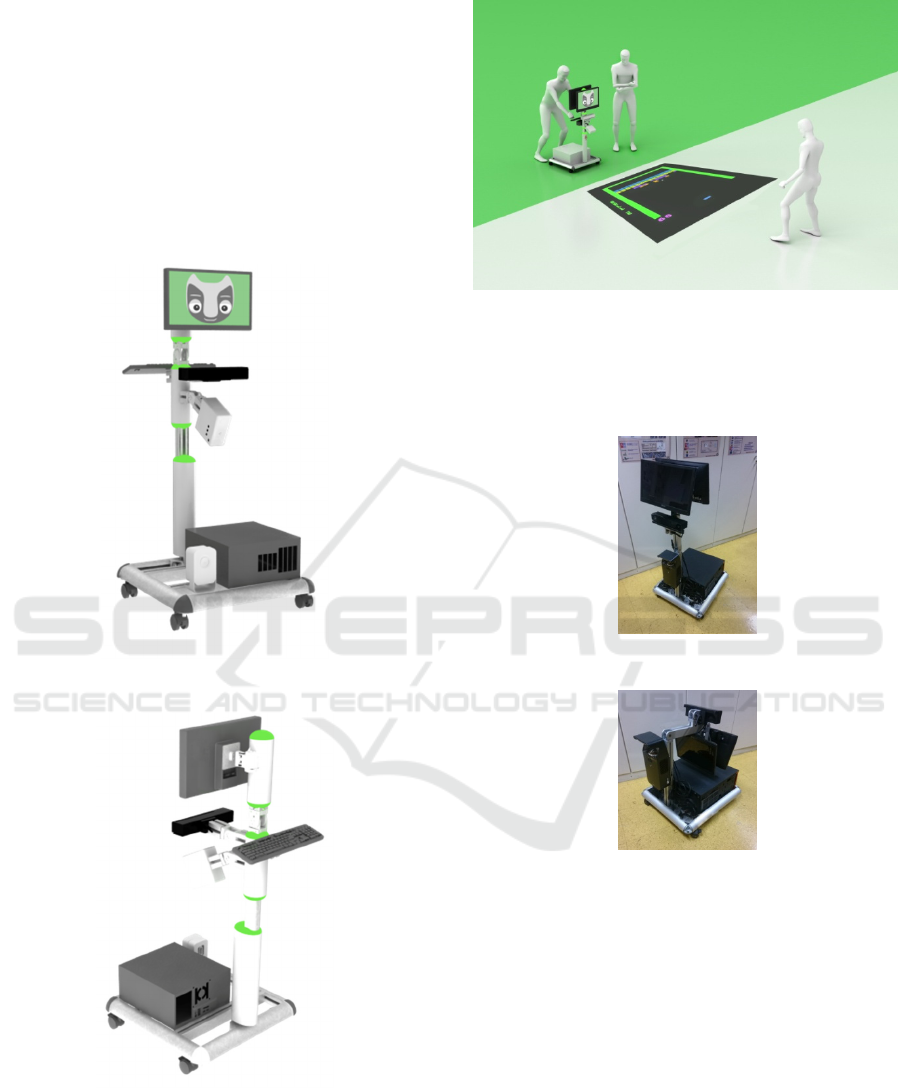

shown in Fig. 2, Fig.3 and Fig.4 The initial requisites

of PEPE are to contain all the hardware required for

the interaction (a computer, a 500-lumen projector, a

Kinect™ v2 sensor, a keyboard and one monitor), and

dimensions that allow easy transportation in a normal

city car boot. This last requirement was the first

verified by the researchers, due to the need to deploy

the system in a short time in several nursing homes.

To meet this necessity, the platform got two rotational

points, to bend the structure and make it smaller, as

can be seen in Figs. 5 and 6, that shows real pictures

of the prototype developed for early testing.

Figure 2: Front View of PEPE.

Figure 3: Rear view of PEPE.

Figure 4: Simulation of the interaction to be performed with

PEPE.

This prototype also served to elicit the participants to

give us their feedback with a visual and functional

perception.

Figure 5: Unfolded PEPE.

Figure 6: Folded PEPE.

4 DESIGN PROCESS - STAGE 2

In order to continue the development of PEPE, we

used an exploratory study in which the elderly and

professionals were consulted on the appearance and

functional aspects of the platform. We took three

group sessions in three institutions, in order to

investigate how the elderly and the professionals

perceive PEPE and the general interaction concept.

The three institutions were based on the geographical

area of Lisboa, Portugal. Focus groups are used for

the discovery of topics related to social involvement

and are a good strategy in revealing diverse opinions

on a particular subject (Morgan, Krueger, & King,

1998). The sessions were orchestrated by an

investigator, who watched, took notes and recorded

audio, and by a professional from the visited

institution. The duration of the three sessions lasted

approximately 60 minutes.

One institution is private more focused on daily

occupation (Institution 1), the two others are senior

residences with occupational and care services (a

public centre Institution 2 and a private senior

residence Institution 3). An experiment was also

carried out in each institution with the real platform,

together with the elderly and professionals that will

be deepened at the end of the second stage (see

Section 4.1)

Participants

To cover a large heterogeneous number of inputs, the

participants are from multidisciplinary areas that

work with the geriatric sector, being: 2 psychologists

(P1) and (P2), 1 gerontologist (G1), 1 Occupational

Therapist (OT1), 1 Physiotherapist (F1), 1 Technical

Director (DT1). A total of 24 elderly people, ranging

in age from 66 to 94 years, were consulted during the

three sessions (5 in the first, 8 in the second and 11 in

the third). Seven participants were male and 17 are

female. Eleven participants had some type of motor

disability.

Procedure

The three sessions were held in three different

institutions in order to gather different social,

economic and ergonomic points of view. At the

beginning of each session, the researcher presented

and contextualized the purpose of his visit to the

institution and the objectives of the process. Each

session consisted of three steps. In the first step, the

participants were questioned about the current

practices of institutions in promoting physical

exercise. The question asked was "How do you

practice physical exercise here in the institution?"

The second step tried to understand the expectations

of the elderly and the professionals regarding

technological approaches in the promotion of active

aging. The third step was related to the presentation

of the PEPE concept and structure. Interviewees were

asked to comment on their adherence to the concept

and guidelines for building and improving PEPE.

This step also dictated the development of three

different appearances to be adopted by PEPE. The last

step was to use PEPE in real usage, where they

experimented with the platform and some technical

aspects were reviewed.

Analysis

Field notes and audio files were then analyzed

through thematic analysis and an inductive approach

(Braun & Clarke, 2006). A number of core subjects

were identified that expressed ideas of participants

during the three sessions. Although some divergences

of opinion have been noticed, most points are

common to all three institutions. This methodology

allowed us to cross different ideas and perceptions.

Results

The main objectives of the sessions were to provide

researchers with guidelines and considerations of the

technical development and appearance of PEPE.

The first issue pointed out by the professionals, is

related to the cognitive and motor limitations of the

elderly, for example dementia or reduced mobility,

that may represent a threat to any solution developed.

One of the stated requirements is that the equipment

must be used also by people in wheelchairs or people

with crutches. The professionals recognise the

advantages and benefits in the practice of physical

exercise, as it can delay some problems of aging and

allows a maintenance of physical condition.

However, it is stated that encouraging some seniors to

practice physical activity and balance exercises may

not be easy because of the lack of motivation. The

common practice for physical activity is based on

rehabilitation, when the person already has some

problem. Desirably, the common practice should be

prevention. At present, the elderly people have

activities that promote exercise, usually in the

morning. These are composed of exercises of

repetitive movements, with series of 10 movements

for each member or worked area. Even if they are

motivated to carry out the activity, it is up to them if

they want to participate in the activity. These

activities are practiced in a group, except in cases

requiring individual monitoring by physiotherapists.

Utility and Predisposition to Acceptance

of Technological Concepts

There is currently a technological scarcity, mainly at

the level of logistical optimization and optimization

of human resources. Due to shortage of staff,

exercises are predominantly developed in group,

resulting in lack of time for individual interactions.

For example, in Inst 2, there is 1 Psychologist to

around 200 older adults. These group activities are

made using traditional tools, with almost no use of

technology. Adaptation to each user was one of the

most critical requirements. We were also alerted to

the need of monitoring in real-time the user vital signs

during the activities to alert the caregiver of any

abnormal event, a practice that is currently non-

existing. A gerontologist mentioned that in addition

to the monitor turned to the person operating the

platform, it might also be interesting to have a

elderly-oriented monitor to enrich the visual

experience as a complement to the projection of the

game. This suggested the addition of a front screen in

the platform, that we decided to be touch sensitive to

increase future possibilities of use with the users.

Professionals stated that the platform design should

have an empathic aspect, so that the levels of

acceptance and participation rates were higher.

Another relevant requirement for professionals, is

that the platform needs to be movable inside an

institution, because many older adults have difficulty

in locomotion, so the platform should be easily

transported between several division in the facility.

This necessity is in accordance with the logistics

requirements of easy transportation, already

mentioned.

Socioeconomic Contextualization of the

Institution and of the Elderly

The main reasons for the lack of technology are

economic and the lack of information on the added

values with respect to classical approaches. Thus, the

professionals have difficulty in communicating the

advantage of the new technological solutions to the

administrative board, which is the decisive factor in

its adoption.

Exploration of Acceptance Among the

Elderly

Elderly were questioned about the general idea of

promoting physical exercise, and about their

willingness to participate in the practice of physical

activity. 19 seniors were receptive to the concept and

willing to perform some activities.

However, 12 affirmed or questioned whether they

could do the activity seated or with some physical

support. The elderly pointed out pain and limitations

in the joints that make it impossible for them to carry

out the activities completely. The remaining nine

subjects mentioned that they would not use the

platform and did not intend to play. The allegations

about this position are related to pain, not liking

physical activity, preference to remain at rest, and the

technology gap (some mentioned that technology is

something not adjusted to the elderly population).

4.1 Interactive Session

PEPE was tested at the Institutions (see Fig. 7 and

Fig. 8). Both elderly and the professionals tested the

different interaction modalities provided by the

platform (playing games while sitting or standing).

This interaction served us mainly to assess the

dynamics of game provided and whether the

specifications of hardware corresponded to the needs

of the elderly.

Figure 7: Demonstration of the platform in Institution 1.

Figure 8: Demonstration of the platform in Institution 2.

5 DESIGN PROCESS - STAGE 3

5.1 Platform Re-design

Based on feedback from the sessions, there were three

main conclusions taken to improve the platform.

First, there is the need for an empathic aesthetics of

the platform. Second, the platform should have two

monitors, one for the elderly and another for the

professional, with adequate graphical elements and

real-time monitoring. The third requirement is in

relation to the games and the capacity they have to

adapt to each user. The aesthetics of PEPE was one of

the most discussed points among the participants. In

the perspective of private institutions, some

professionals believe that PEPE has to have a more

sophisticated and more sober design, “something

premium” (DT1).

On the other hand, the generality of the

professionals, especially in the public institution, a

more emphatic formal language with brighter colours

is more fitting, and several have mentioned that blue

is the preferred colour among people, which is in

agreement with some researchers (Wolchover, 2012)

The third concept was created based on the

opinion of a psychologist and an occupational

therapist, who reveal that a PEPE in white would

make more sense because it does not create additional

visual stimulation - the projection of games is already

a very present visual stimulus. In this way, since

PEPE isused jointly withVizzyin the AHA project

(Fig. 1), we decided to use some aesthetic lines of the

robot and adapt them to PEPE.

The concepts A, B and C are shown in Fig. 9, Fig.

10 and Fig. 11.

Figure 9: Concept A.

The first concept (Figure 9 - Concept A) was created

to respond to a more wide target audience, mainly

because of its colour and most basic formal

appearance. The left side represents the front of the

platform and the right side the back. The aperture on

the front is used to let the projector light through. The

central concept (Figure 10 – Concept B) tries to

Figure 10: Concept B.

Figure 11: Concept C.

respond aesthetically to a higher economy class due

to its metallic and futuristic aspect that gives it a

premium appearance. This version has no front

opening because its coating is unidirectional mirror

film, which makes the carapace transparent and

allows the passage of light from the inside to the

outside. The third concept (Figure 11 – Concept C)

formally derives from the Vizzy robot. In this

concept, the left part corresponds to the rear view and

the right part corresponds to the front view.

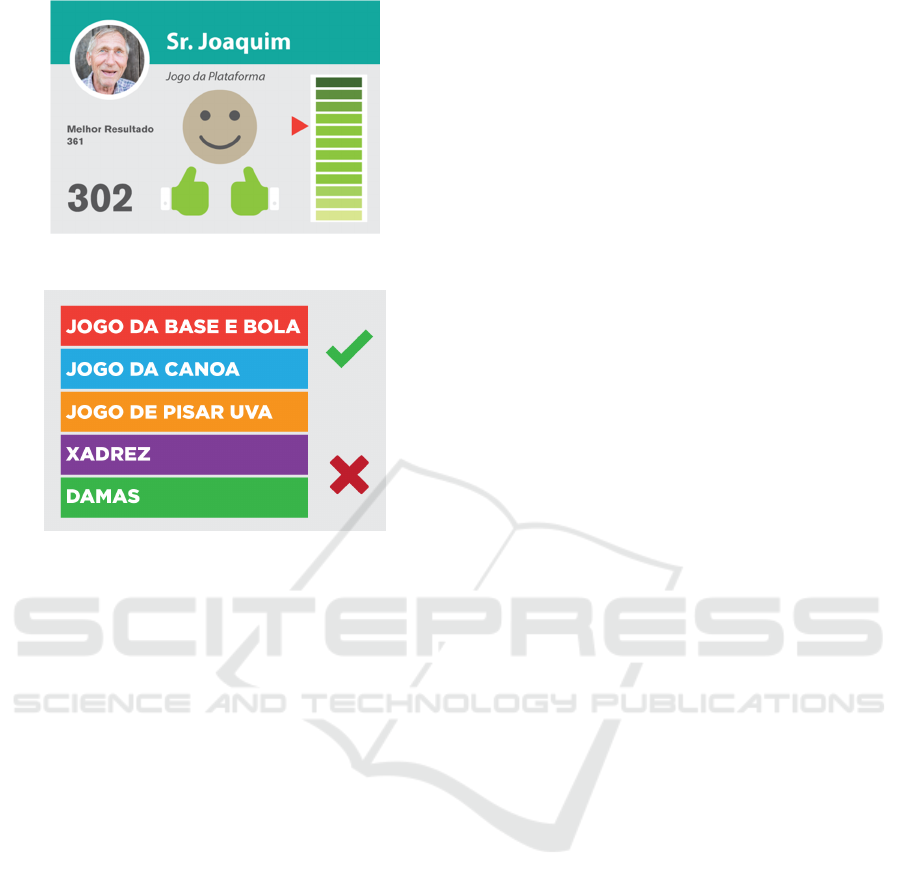

Regarding the information display, three images

have been developed that simulate the graphical

contents that could appear on the screen facing the

user (see screens A, B and C in Figs. 12, 13, and 14,

respectively). Screen A simulates the profile of each

user in which they have access to their physical

provision. Screen B shows the player's previous

score, the current score during the game and the

maximum record reached by any user. This screen is

also based on positive reinforcement, turning green

when the user scores. The last screen (C) was

designed to give the user the opportunity to choose

the game they want to play without a professional.

Figure 12: Screen A. Biometric data.

Figure 13: Screen B. Game scores.

Figure 14: Screen C. Game selection.

5.2 New round of Interviews

After the concepts had been developed upon the

results of the first phase, all institutions were visited

again to carry out questionnaires that quantified the

evaluations. Field notes were also noted for further

analysis. These focused on the appreciation of the

various concepts. Some of the questions asked are

relative to stakeholder preference and what aspects

are relevant to consider.

The results from the first phase (cover designs in Fig.

9, Fig. 10 and Fig. 11 and information display

alternatives in Fig. 12, Fig. 13 and Fig. 14) were

shown to the professionals and users. Additionally,

further concerns on technical, functional and aesthetic

aspects of the platform, as well as the institutions

positioning in the market were made to the

professional. The objectives of this iterative process

were related to perceptions regarding the platform

and needs from the point of view of the elderly. This

option was taken so that both parties could

complement with new observations and feedback the

information provided in the first phase of interviews.

5.3 Evaluation

5.3.1 Cover

We have shown the professionals and the elderly the

different cover designs shown in Fig. 9, 10 and 11.

Each participant voted for the preferred design.

Among the professionals, most votes went to design

A (4 votes), then B (2 votes) and finally C (1 vote).

Empirically, most professionals defended that

concept A is the most empathic and what should

generate greater levels of acceptance, not only due to

the form factor but mainly because blue is more

cheerful and inviting. However, in the opinion of

other interviewees, the elderly has difficulty in

focusing attention, so the platform itself must be an

object that goes unnoticed and does not distract them.

Thus, the white colour of concept C should be more

appropriate. As for the concept B, developed for a

segment of the high class, had the second highest

percentage of votes, however in a chromatic level was

the least empathic and cold-looking. The technical

director of the day care centre (Institution 1) defends

this option is not adjusted to the current older people,

because they are very little technological and this

concept may be too futuristic for the aging population

and be less accepted.

Among the elderly, a sample of 30 seniors with a

mean age of 73.4 years was collected for feedback on

the three concepts. The votes counted correspond to

15 for concept A, 11 for concept B, and 4 votes for

concept C. Analogous to what was pointed out by the

professionals, the elderly users mentioned the most

empathic nature of solution A due to colours and

rounded forms.

5.3.2 Information Display

The first screen, A, was unanimously excluded by the

professionals, who said that elderly people are

already alarmed by heartbeats, and because of this,

this information should only be consulted by the

professional. Screen B was the best accepted, by

professionals and elderly, even because it was said

that there is some healthy competitiveness among the

elderly to play. The last screen was discouraged

because the users had difficulty interpreting its

meaning (selection of the games) and the

professional’s preference in having full control of the

operation of the platform.

6 DISCUSSION

In this section, we describe the main ideas, concerns

and expectations inferred from the sessions of the

design phases and the observations taken during the

interactive sessions. The results presented here derive

from the exposure and interaction with PEPE.

However, the guidelines given below are general and

can be used as guiding lines for the development of

augmented reality technology that promotes the

practice of physical exercise and combat the

sedentary lifestyle in elderly institutions.

6.1 Concerns

Cognitive Deficits

One of the major concerns regards the physical/motor

disabilities that several users have. It was stated that

this type of solution must be used by the maximum

number of possible users. The first reason is to avoid

excluding people or accentuate cognitive or motor

differences. The second reason, as stated by a

technical director (DT1) of an institution, "the more

users can serve, the more it will offset the

investment." To address this problem, some software

modifications have been made that allow seniors in

wheelchairs or seniors who use crutches to play as

well. Also, this locomotion problem in some users is

the principal factor that justifies the wheels on the

platform.

In any case, the generality of the participants

believes that this type of technological approach is

more adjusted to the more autonomous population or

with few physical and cognitive impairments. The

daycare environment was the most indicated because

it has more independent people who can benefit from

these approaches.

Monetary Cost

One of the major concerns raised by professionals is

the cost of such a device. It was declared that it might

not be a democratic product due to its high cost,

which will make it impossible for most institutions to

acquire it. G1 reveals that it can be a costly

investment for a device that brings together

capabilities that will only be used to the fullest by the

minority of people who have no physical or cognitive

impairment. It has also been mentioned that such a

product type, in addition to providing prevention, can

function as rehabilitation or monitoring, thus opening

its range of use and lifetime.

6.2 Expectations

Technological Acceptance

All the interviewees agreed with the potentialities and

optimization of processes that technology can

generate. First, the professionals can save time in

preparing the occupational games since the platform

is very easy to setup and operate. Second, the games

can stimulate simultaneously both the physical and

cognitive aspects, thus reducing the need of having

separate physical and cognitive rehabilitation

sessions. In addition, a portable gaming platform

allows for increased interaction levels and has a broad

range of gaming/activities options that traditional

tools cannot provide. Besides, it was mentioned that

through this type of technological approach, it would

be easier to encourage and motivate the elderly to

participate in physical activities. In addition to

technological proficiency that will become more

common in the coming generations, it is a response to

a societal challenge, not only in the future but today.

As stated by the technical director (DT1) "it is a

necessity because life expectancy is increasing and

you don't watch a paradigm shift. People do not try to

have a healthy and dynamic aging”.

Visual Elements and Color

In visual terms, several professionals argue that it is

important that an object for this segment of the

population has few visual elements. Some

professionals mentioned that usually, objects for the

geriatric section are simplified because they have

some degrees of technological incapacity. This

argument is supported by the study (Habinteg &

Pocklington Trust, 2010), which defends formal

simplicity and suggests intensified contrasts in

objects. The reasons go beyond the positive and

cheerful load that bright colors have (Unicamp,

2008). According to the professional's experience,

colorful tools can represent a strategy of attention

focus and consequently, capacity to pay attention to

the platform. However other professionals have a

different perspective, reporting that an object with

intense colors may have an overly demarcated

presence and may shift user's attention to the object

rather than the action it should take. These defend that

the platform in white or soft colors may be a good

option in this regard. They claim that although they

are projecting animated content on the floor, it is

already quite captivating and that an overly flashy

object will divide the attention.

Infantilization

An important aspect to be considered when designing

products for the geriatric segment is the need to

develop objects which do not increase the social

stigma surrounding the elderly. These warn of the

child load that the object may possess by having

oversized interfaces and buttons, but especially the

games to be realized and projected.

Customization

One of the significant benefits seen in a digital device,

is that it establishes itself with the formal and

multimedia personalization that can be offered.

Personalization creates a sense of belonging and

lowers the rejection rate. Another advantage of

customization is that the platform can represent a

useful personalized stimulation tool already adapted

to each user. This customization is essential not only

for success rates that may be higher (Harriette

Halepis, 2013). It has been suggested by some

professionals that approaches of this kind have to

adapt to the performance and motor and cognitive

capacity of each user. Also, because the geriatric

segment is full of several people with multiple

symptoms that differ from person to person, it was

mentioned that the platform must undergo changes

and mechanical adjustments to fit each case and to

optimize its functionalities depending on the person.

Positive Reinforcement

Some professionals were discouraged when they

realized that the platform did not have any positive

reinforcement that indicated the success rate of the

user. They mentioned that this interaction strategy

might cause users to be motivated for a longer period.

This positive reinforcement can be achieved through

visual or sound cues. It was suggested that part of this

reinforcement could work with verbalizations

indicating the performance of the game. CD1 states

that part of the motivation can also come from a

healthy competition that the game can elicit. It was

expressed that in the ludic activities or traditional

activities, there is a certain competitiveness and even

a collaborative spirit that puts them to carry out the

activity in a more pleasant and motivating form.

Resource Optimization

One of the greatest advantages projected in this kind

of assistive technology approaches is its possible

optimization of data logging. This data can be

accessed by professionals for further analysis. Now,

during the activities, no data is collected regarding the

mobility of the person or physical performance. It was

stated that only rarely these are annotated, typically

on paper, which can give rise to "qualitative

summaries, often information is put as topics". It was

also mentioned that it could be a tool for monitoring

the vital signs of the users and that could contain the

alarm or warning functionality in case of vital signs

anomaly. This kind of process also allows the

development of a history of progress of the various

users, enabling professionals to measure the impact

of their intervention.

Safety

It has exposed the need for security measures that

provide real-time control while the user interacts with

the platform. The professionals must have an

interface that allows them to verify the person's

performance and parameters that indicate the vital

signs or issues related to balance.

Evaluation

The evaluation was considered as one of the most

important issues, not only in validating the concept

and its practical applicability at start, but also

continually during the life of the platform. A good

strategy may be small informal daily questionnaires

made to the population about how they felt playing

and how much they like it. It should be noted that DT1

mentioned that this type of validation among users

will be the determining factor that will dictate future

investment by an institution. In future tests, it will be

useful to understand how PEPE has to be used

regularly to effectively promote active aging and to

understand the impact of this type of technology on

an elderly institution. These tests have to be

performed together with physiotherapists and

psychologists who perform periodic tests in order to

obtain the evolution of the health condition of the

elderly users.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Throughout the iterative design process, we discussed

the social panorama among elderly and the possible

conception of a mobile interaction platform. At the

moment, there is some exploitation of technology in

elderly institutions, but in this research, we added

miniaturization and portability in conjunction with

user-centered design. The tendency with this type of

devices is to increase and become more useful with a

great potential to help both the seniors and the

professionals. The proposed technology allows a

more engaging experience in the exercise and

optimization of resources for the institution. Our

findings demonstrate that users can be proactive in

engaging in exercise with the game platform. The

envisaged benefits include captivating the seniors to

physical activity through games, also increasing

levels of communication and social interaction and

joy. It was unanimous among professionals that this

type of approach must be implemented from the

perspective of promoting physical activity as a

preventive measure. In any case, they recognize that

there are multiple examples of people in institutions

that already have some limitations and that platforms

of this type could be a useful rehabilitation tool. The

main gains are motivation and fun while performing

rehab exercises.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Portuguese Science

Foundation FCT through project AHA – CMUP-

ERI/HCI/0046/2013.

REFERENCES

Abras, C., Maloney-Krichmar, D., & Preece, J. (2004).

User-Centered Design. Encyclopedia of Human-

Computer Interaction. Retrieved from http://www.e-

learning.co.il/home/pdf/4.pdf

Alankus, G., Lazar, A., May, M., & Kelleher, C. (2014).

Towards customizable games for stroke rehabilitation.

Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems CHI 10, (2113),

2113–2122. http://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753649

Allianz. (2014). Baby, It’s Over: The Last Boomer Turns

50. Project M.

Baek, E. O., Cagiltay, K., Boling, E., & Frick, T. (2008).

User-centered design and development. Handbook of

Research on Educational Communications and

Technology, 14(1), 659–670.

http://doi.org/10.1145/1273961.1273973

Bloom, D. E., Jimenez, E., & Rosenberg, L. (2011). Social

Protection of Older People. PROGRAM ON THE

GLOBAL DEMOGRAPHY OF AGING, (83). Retrieved

from http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/pgda/working.htm

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in

pscychology. Qualitative Research in Pscychology.

Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

http://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cohen, G. (2006). Social Protection of Older People. Social

Protection of Older People.

El-Bendary, N., Tan, Q., Pivot, F. C., & Lam, A. (2013).

Fall detection and prevention for the elderly: A review

of trends and challenges. International Journal on

Smart Sensing and Intelligent Systems, 6(3), 1230–

1266. Retrieved from

http://www.s2is.org/Issues/v6/n3/papers/paper23.pdf

Fletcher, R. R., Poh, M. Z., & Eydgahi, H. (2010). Wearable

sensors: Opportunities and challenges for low-cost

health care. In 2010 Annual International Conference

of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology

Society, EMBC’10.

http://doi.org/10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5626734

Francis, P. (2014). Physical Activities in Elderly: Benefits

and Barriers. Human Ageing and Elderly Services.

Retrieved from

https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/77087/

Francis _Purity.pdf?sequence=1

García-Betances, R., Jiminéz-Mixco, V., Arredondo, M., &

Cabrera-Umpiérrez, M. (2014). Using Virtual Reality

for Cognitive Training of the Elderly. American

Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias.

Retrieved from

file:///C:/Users/TOSHIBA/Downloads/AJA_Using

Virtual Reality for Cognitive Training of the

Elderly_version2.pdf

Gerling, K. M., Mandryk, R. L., & Linehan, C. (2015).

Long-Term Use of Motion-Based Video Games in Care

Home Settings. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems -

CHI ’15, 1573–1582.

http://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702125

Gerling, K. M., Miller, M., Mandryk, R. L., Birk, M., &

Smeddinck, J. (2014). Effects of Skill Balancing for

Physical Abilities on Player Performance, Experience

and Self-Esteem in Exergames. CHI 2014, (Exergame

Design). http://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2556963

Gonzalez, M. F., Facal, D., Buiza, C., Urdaneta, E., Köffel,

C., Geven, A., … Soldatos, J. (2008). HERMES –

Cognitive Care and Guidance for Active Aging D.6.1

Cognitive Training Exercises. Hermes.

Gulliksen, J., Lantz, A., & Boivie, I. (1999). User Centered

Design in Practice - Problems and Possibilities.

SIGCHI Bulletin, 31(2), 25–35.

http://doi.org/10.1386/jmpr.2.1.30

Habinteg, B., & Pocklington Trust, T. (2010). Design

Guidance for people with dementia and for people with

sight loss.

Harriette Halepis. (2013). Having It Their Way: The Big

Opportunity In Personalized Products. Retrieved

February 25, 2017, from

http://www.forbes.com/sites/baininsights/2013/11/05/

having-it-their-way-the-big-opportunity-in-

personalized-products/

Harvey, J. A., Chastin, S. F. M., & Skelton, D. A. (2013).

Prevalence of sedentary behavior in older adults: a

systematic review. International Journal of

Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(12),

6645–61. http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10126645

Hirvensalo, M., Heikkinen, E., Lintunen, T., & Rantanen,

T. (2005). Recommendations for and warnings against

physical activity given to older people by health care

professionals. Preventive Medicine, 41(1), 342–347.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.020

Khoo, E. T., & Cheok, A. D. (2006). Age Invaders: Inter-

generational Mixed Reality Family Game. The

International Journal of Virtual Reality, 5(2), 45–50.

Retrieved from

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c80f/20de038485c079

20a71452a47846a32a0202.pdf

Maczka, M., Parry, D., & Curry, R. (2015). The Sehta

Review Technology and Innovation in Care Homes.

Setha.

Mader, S., Dupire, J., Natkin, S., & Guardiola, E. (2012).

Designing Therapeutic Games for Seniors : Case Study

of “ Le Village aux Oiseaux .”

Mandryk, R. L., & Gerling, K. M. (2015). Discouraging

Sedentary Behaviors Using Interactive Play.

Interactions, 22(3), 52–55.

http://doi.org/10.1145/2744707

Mendoza-Ruvalcaba, N. M., & Arias-Merino, E. D. (2015).

“I am active”: effects of a program to promote active

aging. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 829–37.

http://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S79511

Moreno, P., Nunes, R., Figueiredo, R., Ferreira, R.,

Bernardino, A., Santos-Victor, J., … Aragão, M.

(2016). Vizzy: A humanoid on wheels for assistive

robotics. Advances in Intelligent Systems and

Computing, 417, 17–28. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-

319-27146-0_2

Morgan, D. L. (Sociologist), Krueger, R. A., & King, J. A.

(1998). Focus group kit. SAGE Publications. Retrieved

from

https://books.google.pt/books/about/The_Focus_Grou

p_Kit.html?id=dFE_XwAACAAJ&redir_esc=y

Nations, U. (2015). World Population Ageing 2015. United

Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs,

Population Division.

Nintendo. (2009). Wii Operations Manual System Setup.

Omholt, K. A., & Wærstad, M. (2013). Exercise Games for

Elderly People. Identifying important aspects,

specifying system requirements and designing a

concept, (June), 1–223.

Pasqualotti, A., Barone, D. A. C., & Doll, J. (2012).

Comunicação, tecnologia e envelhecimento: idosos,

grupos de terceira idade e processo de interação na era

da informação. Saúde E Sociedade, 21(2), 435–445.

http://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-12902012000200016

Playstation. (2009). Comando de movimento PlayStation

Move | Mais formas de jogar | PlayStation. Retrieved

February 24, 2017, from

https://www.playstation.com/pt-

pt/explore/accessories/playstation-move-motion-

controller/

Rantanen, T. (2013). Promoting mobility in older people.

Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health =

Yebang Uihakhoe Chi

, 46 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S50-4.

http://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.2013.46.S.S50

Ribeiro-Papa, D., Masseti, T., Crocetta, T., Menezes, L., &

Antunes, T. (2016). Motor learning through virtual

reality in elderly - a systematic review. Medical

Express. Retrieved from

file:///C:/Users/TOSHIBA/Downloads/v3n2a01.pdf

Rice, M., Wan, M., Foo, M.-H., Ng, J., Wai, Z., Kwok, J.,

… Teo, L. (2011). Evaluating gesture-based games

with older adults on a large screen display. In

Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGGRAPH Symposium

on Video Games - Sandbox ’11 (p. 17). New York, New

York, USA: ACM Press.

http://doi.org/10.1145/2018556.2018560

Sinclair, J., Hingston, P., & Masek, M. (2007).

Considerations for the design of exergames.

Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on

Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques in

Australia and Southeast Asia, ACM(December), 289–

295. http://doi.org/10.1145/1321261.1321313

Skelton, D. A., & Dinan-Young, S. M. (2008). Ageing and

older people. In Exercise Physiology in Special

Populations (pp. 161–223). Elsevier.

http://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-10343-8.00006-8

Udayshankar, P. M., & Parameaswari, P. J. (2014). Healthy

and active ageing. World Applied Sciences Journal,

30(7), 927–928.

http://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wasj.2014.30.07.82124

Unicamp. (2008). Luz e Cor. São Paulo: Nova Alexandria,

1–18. Retrieved from

http://www.iar.unicamp.br/lab/luz/ld/Cor/luz_e_cor_.p

df

Wolchover, N. (2012). Humanity’s Favorite Colors |

What’s Your Favorite Color? Retrieved September 4,

2017, from https://www.livescience.com/34105-

favorite-colors.html