Design Methods for Personified Interfaces

Claudio S. Pinhanez

IBM Research, São Paulo, Brazil

Keywords: Personified Interfaces, Design Methods, Chatbots, Humanoid Robots.

Abstract: Recent advances in natural language processing, computer graphics, and mobile computing are driving a

new wave of interfaces, called here personified interfaces, which have clear and distinctive human-like

characteristics. The paper argues that personified interfaces need to portray coherent human traits, deal with

conflict, and handle drama, driving a need of new design methods. Using theoretical frameworks drawn

from different disciplines, concisely described in the paper, four design methods are presented to support the

design of personified interfaces, merging traditional design techniques with the use of personality models,

improvisational theater techniques, comics-inspired storyboards, and even some ideas from puppetry and

movie animation. The design methods are exemplified with results from three student workshops aimed at

designing a service recovery interface for e-commerce.

1 INTRODUCTION

From the beginning of the 2010s computer interfaces

based on speech, chat, and avatars have started to

reach everyday consumers. Personal mobile

assistants such as Siri and Cortana, voice-activated

speakers such as Echo and Google Home, and

chatbots of all kinds and purposes have left the

laboratories and have become a part of people’s

daily conversations. At the same time, humanoid

robots such as Nao and Pepper, conversational toys,

and automotive systems have incorporated

interactive speech and voice capabilities.

In most of those cases the interfaces exhibit

typical human traits such as personality, gender,

sentiments, and even the appearance of

consciousness. Although research has shown that

there is almost always some level of humanization in

any interaction with computers (Reeves and Nass,

1996), the introduction of speech, chatting

capabilities, and humanoid embodiments seem to

trigger behaviors from users resembling those used

to deal with other human beings. Users greet, thank,

yell at, mock, curse, and play with those interfaces

in a way quite different from when they use a

traditional point-and-click interface.

We use the term personified interfaces to

describe interfaces which display human traits such

as personality, gender, and character; and the term.

personified machines to name the systems which

employ personified interfaces. In our view, the key

novelty is that personified interfaces tend to elicit

typical human-to-human behaviors from their users

which are not usually seen in traditional interfaces.

However, most principles and practices used

today in interface design assume that users are

interacting with pure machine systems and not with

personified machines. The goal of this paper is to

discuss how different should be designing a

personified interface and to propose principles,

theoretical frameworks, and some design methods to

address the challenges of this context for designers.

In this paper, we argue that personified interfaces

need to be designed to convey coherent human

traits and personality, to engage in sound social

behaviors, to be embodied through consistent

actions, and to be able to participate in dramatic

stories co-created with their users.

This work adapts and expands some early work

we did in the design of service systems (Pinhanez,

2014). Because service providers have a tendency to

be personified by their users, in that work we

proposed a design methodology to improve service

quality by understanding the personification issues

and address them in the design of the service

processes of the interface, but without personifying

it. Here we apply some of the same methods to meet

the design requirements of a personified interface.

We start by discussing what we see as the main

requirements which distinguish the design of

Pinhanez C.

Design Methods for Personified Interfaces.

DOI: 10.5220/0006487500270038

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2017), pages 27-38

ISBN: 978-989-758-267-7

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

personified interfaces from traditional interfaces. We

argue that personified interfaces must exhibit

coherent human traits, must deal with conflict with

their users, and must be able to handle drama. We

then explore theoretical frameworks to support the

design of the human traits of the personified

interface and its embodiment, personality, and social

behaviors; and to enable the interface to manage

conflict and fulfil dramatic roles. We then explore

four design methods inspired by the ones proposed

in (Pinhanez, 2014), using examples from the

student workshops conducted in the original paper.

Our aim is to construct personified interfaces

which create rich, meaningful, and trustable

interactions with the user. Unfortunately, many of

the personified interfaces designed to date seem to

portray something like a caricature of a human

being. At the best, some of those personified

interfaces are cute; at worst, they become annoying

after a couple of interactions (like Clippy, the

infamous interface character introduced in Microsoft

Office in the 1990s).

2 PERSONIFIED INTERFACES

The discussion throughout this paper is based on

three fundamental requirements we believe most

personified interfaces need to meet:

1. personified interfaces must exhibit coherent

human traits and social behaviors;

2. personified interfaces must be able to deal

with conflict with their users;

3. personified interfaces must handle dramatic

narratives created by their users.

It is not the goal of this paper to provide

empirical evidence of the validity of each of the

three requirements but instead to explore how we

believe they guide the design process in theory and

practice. The requirements can be treated as our

working hypotheses for this paper and we will not

try to validate them experimentally here. We

acknowledge that this validation is needed, using,

for instance, methods such as structured interviews,

focus groups, user surveys, and experiments such as

the ones described in (Reeves and Nass, 1996) but

this validation is beyond the scope of this paper.

In the conversations we have had with design

professionals about those requirements, most of

them found them relevant and agreed that they are

likely to be present in most scenarios of personified

interfaces. The main point of content we got from

designers has normally been how those requirements

can be met by the design process. But before we

explore this issue, it is necessary to clarify better

what we mean by each of three requirements.

2.1 Coherent Human Traits

Users have a strong tendency to attribute human

characteristics to objects, places, and machines, and

change interaction patterns accordingly (Reeves and

Nass, 1996). In the cases where machines produce

voice or text, users have shown to recognize gender,

personality, and race in spite of being aware that

they are interacting with machines (Nass and Brave,

2005). Moreover, users of conversational systems

exhibit social behaviors typically associated with

other human beings, such as similarity

attraction (Tajfel, 1981). For instance, Lee et

al. (Lee et al., 2000) showed that not only male users

liked more interacting with “male” computers but

also that they trusted them more (and vice-versa).

Many experiments have shown that people react

negatively when faced with a personified interface

with incoherent human traits (Nass et al., 2006).

In (Nass and Najmi, 2002), subjects listened to

descriptions of products recorded by Caucasian

Americans and first-generation Koreans, which were

cross-matched with faces of Koreans and Caucasian

Australians. When subjects heard descriptions with

Korean accents matched to Caucasian faces they

react negatively, and vice-versa, not only disliking

the voices but also rating less favourably the

products described.

The reality is that most personified interfaces

today are designed without regard for those

principles and ideas. In the absolute majority of

cases, the human traits of personified interfaces are

not addressed in the design process and left to be

created by the user’s imagination during the

interaction process. To avoid this, we believe that a

personified interface should be coherently structured

around clear definitions of its gender, race, level of

schooling, personality, etc., designed with the help

of some of the methods described later.

2.2 Dealing with Conflict

As (brilliantly) pointed out by Daniel Dennett, the

complexity of most (pure) computer systems is

better dealt with by the intentional stance, in which

the user understands the system and predicts its

behavior not by knowing how it works but “… by

ascribing to the system the possession of certain

information and supposing it to be directed by

certain goals, and then by working out the most

reasonable or appropriate action on the basis of

these ascriptions and suppositions.” (Dennett,

1981), pp. 224.

In personified interfaces users have additional

reasons to adopt the intentional stance right away as

the framework for the interaction. If a machine talks

to a user or has a humanoid body, human beings

have a hard time not thinking that the machine has

its own intents and desires, and feel compelled to

respond taking that fact in account. Personified

interfaces tend to intensify the adoption of the

intentional stance by their users.

However, quite often the intents and goals

ascribed by the user to the personified machine are

different from the user’s own intents and goals. For

instance, when the interfaces are part of the

interaction with an organization (such as in a

corporate chatbot), there is often a clear and real

difference in the goals of the machine/organization

and the user, as we discussed at length in (Pinhanez,

2014). We believe that this gap between the goals of

the user and the perceived goals of the machine

breeds conflict.

Studies of actual interactions with today’s

conversational systems often portray cases of

conflict and frustration. In a qualitative study of

Apple’s Siri, (Luger and Sellen, 2016) found many

instances where failures of a conversational agent

where perceived as its stubbornness. Similarly, most

people believe that the phone answering systems do

not understand them purposefully in many

situations, such as when closing a service account.

In personified interfaces, we expect that the

tendency for the machine to be perceived as in

conflict with the user is likely to more pronounced

than with non-personified systems. We believe that

we will see users regarding machines as mean,

stubborn, selfish, and arrogant as they argue with

them or see them pursuing goals different from

theirs. The important question for designers is how

this conflict can then be managed and, if possible,

mitigated. For that, we propose to look into how

human-human conflicts are dealt with, that is,

through social norms and constructs, and apply

conflict resolution techniques to the design of

personified interfaces.

2.3 Handling Drama

One way people use to make sense of their

interactions with other people in life is to mentally

represent their interactions as dramatic narratives.

By making themselves heroes or victims and by

rendering other people as gods or villains, people

can more easily make intentions, values, and goals

explicit. And by using narrative structures such as

causation, succession, and counterpoint, the

representation of the complex temporal patterns of

our social life becomes more manageable.

Similarly, we have seen that interaction with

personified machines tends to be dramatized in a

narrative by the user. The idea of narratives as

representations or cognitive foundations for

interaction is not new to HCI theory as, for example,

in (Laurel, 1991). The key difference in the case of

personified interfaces is that the narrative almost

always becomes dramatic: personified machines can

easily take the role of friends, gods, villains, or

sidekicks in the narrative.

For instance, users often report their initial

experiences with speech-based personal assistants as

a story of high expectations and deceit (Luger and

Sellen, 2016). They start asking really difficult

questions to the machine, get disappointed with

basic mistakes, resort to ask for jokes or other form

of play, and finally use it for menial tasks. We

contend that to make a personified interface work in

the real world requires designing it to survive (and

possibly break) this first tale where the personified

interface is made to play the roles of a fortune teller,

an idiot, a jester, and finally a servant.

Handling of dramatic structures in personified

interfaces is an important requirement whose need

often only surfaces in longer, more complex, or

more conflicting interactions. Nevertheless, we

believe personification dramatically changes the

users’ perception of the actions and responses of a

personified machine and therefore designers should

try to prepare the interface to deal with the stories

their users are likely to co-create to explain and

represent their sequence of interactions.

3 THEORETICAL

FRAMEWORKS

If personified machines need to have coherent

human traits, deal well with conflict, and handle

drama, an important set of questions arise for

personified interface designers. To what extent the

personified interface must be constructed to be

perceived as an “artificial” human being, that is,

how much do they need to personify the interface?

Which are the human traits and characteristics more

often perceived and are needed by the users? When

and how do users treat — and would like to treat —

personified machines with courtesy? How to design

interfaces which highlight particularly desirable

human traits? How can the interface drive the drama

behind the interaction process constructed by the

user and better participate in it?

To address those issues, we introduce the

concept of the interface persona which is simply the

“human being” personified by the interface. The

interface persona is the result of the combination of

the personified interface’s visual appearance, its

style of speaking and writing, its action affordances,

and the internal processes which are responsible for

generating and controlling the interface.

We postulate here that for a personified interface

to meet the requirements discussed before,

adequately designing the interface persona is a

fundamental part of the process. That is, the

(coherent) human being perceived by the users in

their interaction with the personified machine must

be the object of a targeted design process using

specific design methods such as those described in

section 4.

However, human beings are complex creatures

and therefore we should not expect that designing

interface personas and constructing effective

personified interfaces to be a simple task. Also, bad

persona interface design is as easy to recognize as a

poor characterization or bad acting in theatre or

movies. To tackle those challenges, we propose to

ground the design process in solid and tested

theoretical frameworks which have been used in

other disciplines to understand and, in some cases,

“create” human beings (such as in theatre). We

explore here some of those frameworks which we

believe can be useful foundations for conceiving,

designing, and constructing personified interfaces

and their interface personas.

3.1 Human Traits in Interaction

As mentioned before, there is a lot of evidence that

users tend to assign human traits such as gender,

personality, and emotions to all kinds of systems,

including cars, television sets, and traditional

computer systems (Reeves and Nass, 1996). In

particular, research has shown that people perceive

gender even in the absence of explicit cues, for

instance, from the writing style (Newman et al.,

2008). Gender is important because people have

biases for specific genders to help them in specific

tasks. For instance, Lee et al. (Lee, 2003) showed

that subjects in a shopping task prefer to take advice

from computers with male voices about cars and

from female voices about beauty products.

Experiments have also shown that people have

similar reactions towards perceived race and place of

origin in conversational systems (Giles and Scherer,

1979). All this point towards the need to clearly

define to which gender and race an interface persona

belongs.

Pursuing neutral instances of gender and race

seems to be a path to be avoided. Studies in

psychology have shown that people who manifest

inconsistent personalities and traits are often

perceived by their interlocutors as incapable,

unpredictable, or liars, and the same has been

demonstrated for computer systems and in

particular, for conversational systems (Nass and

Brave, 2005). (Nass and Najmi, 2002) describes

experiments where users, when interacting with

conversational systems with inconsistent personas,

tend to not only to dislike more those systems (in

comparison to coherent personas), but also that

inconsistency is extremely impactful to the

accomplishment of the task by the users.

A further complicating issue is the tendency of

people to like people who are similar to them, as

discussed in (Tajfel, 1974), subsequently expanded

to what is generically known as similarity

attraction (Tajfel, 1981). The principle applies also

for interfaces: male users tend to prefer “masculine”

conversational systems, while women are more

likely to prefer “feminine” system personas (Nass

and Brave, 2005, Reeves and Nass, 1996);

extroverted people prefer “extroverted”

systems (Nass and Lee, 2001); and similarly to race,

ethnicity, emotions, and education — although this

effect is sometimes moderated by type of task and

cultural biases. A key consequence of similarity

attraction is that in many cases there is not a right

gender, race, or other human trait for a given system.

Those human traits should match the corresponding

traits in the user, stressing the need of some form of

choice or personalization of the interface persona.

3.2 Character Embodiment

When the personified interface employs a visual,

humanoid embodiment, such as in virtual humans or

robots, all the issues discussed in the previous

section seem to apply, if not made stronger (Li et al.,

2016, Breazeal, 2003), and therefore we will not

explore them again in the context of embodiments.

We focus here in the issue of how embodied

personified machines move, gesture, speak, and act,

as a way to express their human traits, sentiments,

and goals. To help the design and construction of

personified interfaces, we are exploring and using

techniques used in arts and entertainment for

character embodiment, such as the Stanislavski’s

system, willing suspension of disbelief, and illusion

of life. Such concepts and techniques address how to

make the interface persona look real, inspire trust,

and play effectively its personality, social behaviors,

and story role.

Stanislavski’s system is the name associated with

the methods of Konstantin Stanislavski who is often

credited as the pioneer of modern acting techniques

in theater. Departing from the tradition of reliance

on facial expressions, excessive gesturing, and voice

manipulation, Stanislavski focused on physical

action: “Acting is doing.” The best embodiment of a

character does not pretend to be the character

through facial expressions or display of emotions:

they perform actions which manifest their emotions

and goals (Stanislavsky, 1949). Considering this,

personified machines should not display sad faces in

case of failures: regret is better expressed with acts

of repair and renouncing, such as giving a voucher

to compensate for a service failure. Acting is doing.

An alternative body of knowledge can be used

borrowing from concepts and techniques from

puppetry and movie animation, whose fundamental

quest is to vent humanity onto inanimate objects and

drawings. Puppetry deals almost always with the

physical limitations of the puppet, with its inability

to speak, to move, to have facial expressions, and to

perform complex gestures. The key lesson from

puppetry is to choose stories and roles which can be

conveyed by the affordances of the puppet. Hand

puppets convey most of their character through

head, torso, and arm movements, and by

occasionally transforming the body into a hand, so

they are not suited for narratives with long dialogues

or require facial expressions; shadow puppetry uses

the flat borders between black and white worlds to

convey the intricacy and beauty of the characters, so

it works best for contexts rich in singing or poetic

soliloquies.

At the same time, puppetry shows that it is

surprisingly easy to make audiences believe that

there is an intelligent, emotional human being inside

every puppet (Blumenthal, 2005). By matching

carefully the story (or interaction) to the right, albeit

minimal, set of affordances, it is possible to portray

characters who look alive, caring, loving, hating, and

interacting with other puppets and the public. Less is

sometimes more in embodied personified interfaces.

Puppetry takes to extremes the key dramatic

notion of willing suspension of disbelief (proposed

as the center of storytelling by poet Samuel

Coleridge in 1817). Audiences must suspend their

disbelief that the puppets are not real people. A

technique often used in puppetry to help the

suspension of disbelief is the exposition of the

materials and inner workings of puppets, making

them move in non-realistic ways, or openly

showcasing the puppeteer on the stage as in bunraku

theatre (a traditional Japanese puppet art). Doing so,

puppeteers amplify the need of willing suspension of

disbelief and in the process, create larger empathy

between audience and characters. An example of

this principle in a chatbot is when it displays

alternative understandings of an utterance from the

user, and ask the user to choose the option that best

represents what he or she means. By exposing

(instead of hiding) its limitations such chatbot not

only improves the overall interaction but also

increases the confidence and trust of the user in it.

Similarly, there are lessons to be learned from

movie animation which have similar challenges in

animating drawings to convey emotions and humor.

In the quest for what is referred to as the illusion of

life, a set of 12 fundamental principles of animation

was compiled by Walt Disney’s animators in the

1930s (Thomas and Johnston, 1981). For example,

the anticipation principle states that “[the audience]

must be prepared for the next movement and expect

it before it occurs. […] Before Mickey reaches to

grab an object, he first raises his arms as he stares

at the article, broadcasting the fact that he is going

to do something with that particular

object.” (Thomas and Johnston, 1981), pp. 52.

In personified interfaces, we can apply

anticipation by making sure that an important action

such as charging a credit card is clearly anticipated

by actions which potentially could be stopped by the

user: after the user agrees verbally, there can be a

depiction of the preparation for charging which

allows one more chance for the user to change her

mind. Other fundamental principles of animation

such as staging, follow through and overlapping

action, arcs, secondary action, timing, exaggeration,

and appeal (Thomas and Johnston, 1981) may also

be applied in the design of personified interfaces.

We do not explore them further in this paper due to

space restrictions.

3.3 Personality Archetypes

There is a vast number of proposed personality

models of human beings, well beyond what could be

explore in the context of this paper. We have been

employing personality theory, a general name for

psychological models which assign archetypal

categories of personality to human beings, aiming to

help predict the effects of having each archetype in a

context or how each archetype normally interacts

with people of the other archetypes.

There are two basic streams of personality

archetypes. The first stream is based on the Lexical

Hypothesis of Sir Francis Galton and has been

applied to fundament the use of five broad

dimensions to describe personality traits, commonly

known as Big Five or OCEAN for their initials

(Norman, 1963): Openness, Conscientiousness,

Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (or

Need for Stability). Openness is a dimension that

describes how much the person is attracted to new

experiences. Conscientiousness describes how much

the individual can control his or her impulses and

emotions. Extraversion relates to how much the

person can communicate and engage with others.

Agreeableness describes the ability to befriend and

cooperate with other people, and to be concerned

with their well-being. Neuroticism refers to the level

and need of emotional stability.

The second stream of personality archetypes has

its origins in Jung’s Psychological Types (Jung,

1976) which influenced, among many, the works of

Myers and Briggs, who created the Myers-Briggs

Type Indicator (MBTI) (Myers, 1998) which

classifies individuals along four dichotomies:

Extraversion vs. Intraversion (E-I), the preferred

mode to acquire energy and motivation; Sensing vs.

iNtuition (S-N), determining the preferred mode to

obtain information; Thinking and Feeling (T-F),

referring to the decision-making mechanism of

choice; and Judging vs. Perceiving (J-P) indicating

the preferred mode to relate to the world, using T-F

or S-N channels, respectively. The four preferences

define the 16 MBTI types: ESTJ, ESTP, and so on.

More popular personality archetypical methods

are horoscope signs, of which the most known are

based on the Sun sign astrology (Leo, Virgo, etc.)

and on the Chinese zodiac (Rabbit, Monkey, etc.).

Let us not get distracted here by the validity of

whether stars and planets can influence the

personality of person and what will happen to her.

The reality is that horoscope signs are an interesting

compendium of 12 basic human archetypes which

most people are extremely familiar with, and

therefore can comfortably use in the design process

of the personality of the interface persona.

Describing an interface persona as being Leo is, for

most people, simpler to understand than saying it has

a INFJ type.

Personality theory can make concrete and

communicable to the different stakeholders in the

design process the personality traits that should be

present in the interface persona. For instance, if a

chatbot should be perceived as nurturing, patient,

pragmatic, loving, methodical, dedicated, and

flexible, it may be just simpler to say its interface

persona is a Virgo.

3.4 Social Behaviors and Emotions

Psychology has a long tradition of debating the

relative importance, differences, and relationships

between the personal and social aspects of the

individual. Social psychology is one of the

disciplines we can draw ideas and concepts from. It

focuses on how social context affect human beings

and how people perceive and relate to each other,

therefore providing a theoretical framework to

examine the interactions between users and

personified machines. With the risk of some

oversimplification, we can say that there are two

basic currents in social psychology, coming from the

psychological and sociological traditions

respectively. For lack of space in this paper, we only

examine basic ideas of the psychological stream,

often associated to Kurt Lewin’s work (Lewin and

Gold, 1999).

Social psychologists from this tradition divide

the social phenomena into two spheres:

intrapersonal and interpersonal. Intrapersonal

phenomena of interest include the study of attitudes,

or basic likes and dislikes; persuasion; social

cognition, or how people collect, process, and

remember information about others; self-concept, or

how people perceive themselves; and cognitive

dissonance, the feeling that someone’s behavior or

self-concept are inconsistent. For instance, cognitive

dissonance increases whenever people voluntarily

do activities they dislike to achieve a goal.

Paradoxically, doing this cause the perception of the

value of the goal to be increased. For instance, when

users must work with a difficult interface they value

the accomplishment of the task more than if they

were using an easy interface (somewhat contracting

the whole goal of the interface design), as noticed in

some studies on the use of voice-based personal

assistants (Luger and Sellen, 2016).

Among interpersonal phenomena studied in

social psychology which may be relevant to the

design of personified interfaces, we can list: social

influence, or how conformity, compliance, and

obedience manifest themselves; interpersonal

attraction, including propinquity, familiarity,

similarity, physical attractiveness, and social

exchange; and interpersonal perception, which

includes issues related to the accuracy, self-other

agreement, similarity, projection, assumed

similarity, reciprocity, etc. For example, in

interpersonal attraction, it is often true that the more

someone interact with a person, the more likely she

is to become emotionally engage with that person, or

the propinquity effect. Personified systems which are

often interacting with the users, such as one-button

smartphone assistants or always-on ubiquitous

speakers, will tend to be better perceived by human

beings than an app-based personified interface

which must be launched every time is used.

Another important aspect of the social behavior

is related to how emotions are used to convey and

mediate social interaction between human beings.

Emotional communication theory, which aims to

understand how emotions are used in the context of

interpersonal communication, is therefore an

important source of models for the design of social

behavior of personified machines. Although research

on emotions goes back to Darwin in the 19th

century, the field experienced an extraordinary

growth in the 1990s (Andersen and Guerrero, 1998).

Several categorizations of emotion types have been

proposed, including Ekman’s (Ekman and Friesen,

1975) which proposed happiness, sadness, fear,

surprise, anger, and disgust as the most basic

emotions, expressed and recognized in almost any

cultural group on Earth. A more complete model to

use is Plutchik’s sentiment wheel (Plutchik, 1980)

which adds anticipation and trust as basic emotions,

describes variations of intensity in each emotion,

and assigns colors to them. For instance, the anger

scale starts with rage, passes through anger, and

softs with annoyance, going from a deep red to pink.

3.5 Narrative Theory

We all construct in our minds dramatic stories to

better explain the world and the behavior of the

people around us. We believe the same applies in

this context, that is, users have a strong tendency to

construct and justify their relationship and actions

with a personified machine by means of a “made-

up” dramatic story the users and the machine are

part of, and in which they play different characters.

To model this process, we employ a dramatic

framework called narrative theory, initially laid

down by Vladimir Propp, a Russian formalist who

collected and studied hundreds of folktales and

proposed that there is a common typology of

narrative structures (Propp, 1968). It is based on

common subsequences of 31 basic steps and the

identification of 8 basic roles played by what he

calls dramatis personae, or the characters involved

in a typical plot: hero, villain, donor (who prepares

the hero for his journey), helper, princess, princess’

father, dispatcher (who sends the hero off), and the

false hero/anti-hero/usurper.

Propp claims that all folktales have similar

characters and narrative structures, given and take

some characters and plot steps. Similar claims can

be found in the work of Joseph Campbell on

mythology and mythical heroes (Campbell, 1996),

which identifies similar structures across

mythologies around the world; and in Vogler’s

discussion of Campbell’s work (Vogler, 2007)

which is extensively used in character and narrative

development by the entertainment industry (for

instance, by George Lucas in the Star Wars saga).

We believe that the interaction of a user and

personified machine is often constructed cognitively

and emotionally as a dramatic narrative where the

user sees herself as the hero. The key question for

the designer is which role(s) the interface persona

should aim to portray in such a narrative. The

interface persona could be the donor, the helper, or

even the princess’ father (the gatekeeper to the

user’s goals), although, in many times, it inevitably

becomes the villain.

To help, character theory has some of the

concepts necessary to understand not only how to

construct the story character but also to define the

different roles of the interface elements in the “fairy

tale” encounter with its user. Character theory

provides designers with a structure for human

interaction with the personified interface based on

powerful, deeply engrained psychological structures

built on people from their childhood.

To finalize this discussion of dramatic models it

is important to point out that many of the discussed

techniques for character, story creation, and

enactment aim to maximize conflict, which is a

major engine of drama in theater and entertainment.

However, in the context of personified interfaces, we

may find often that the desirable interface persona is

the one precisely with the opposite property, that is,

an interface that minimizes conflict with the user. In

that sense, it may be necessary to repurpose the

discussed dramatics models to arrive at models that

are more appropriate for less conflict-prone interface

personas.

4 DESIGN METHODS FOR

PERSONIFIED INTERFACES

After having presented and discussed some key

requirements personified interfaces have and

explored fundamental theoretical frameworks, we

present here some design methods we have been

developing to address those specific requirements in

the design process of personified interfaces. We

firmly believe that many of the traditional design

methods used in computer-human interaction are

also applicable to personified interfaces, since there

are many interface challenges which are basically

related to the communication media. We implicitly

assume here that the overall personified interface

design process must also apply traditional concepts,

methods, and steps of a user-centered design such

as, for example, the construction of user

personas (Pruitt and Adlin, 2006).

However, the methods discussed in this section

exemplify in concrete terms the need of additional

work to systematically expose and target the

intrinsic difficulties of creating personified

interfaces. Inspired by the frameworks techniques

from social sciences, theater, puppetry, and social

psychology discussed in section 3, we describe here

four design methods: personality workshop, conflict

battle, comics workshop, and puppet prototyping.

The design methods were inspired in previous

work on service design (Pinhanez, 2014). They were

originally developed to address issues in the design

of computer interfaces to service systems,

specifically the process of personification of the

service provider which often occurs during service

recovery. Service recovery is often a very

conflicting process where users see themselves

battling against (personified) corporations. In this

paper, we repurpose those methods in the more

general context of personified interfaces.

We have explored those service design methods

in three workshops with students in the context of

designing the service recovery interface for a self-

service e-commerce website. Although we have not

yet used the repurposed design methods in de facto

contexts of design of personified interfaces, we

include here some of the results of those workshops

because they do a great job in exemplifying the

methods and the kind of results we are seeking.

The service design workshops were structured as

follows. First, participants were presented with the

problem of designing the service recovery interface

of a web-based delivery failure system for an

imaginary small website for expensive, fashionable

sneakers called powersneakers.com. As part of the

input to the participants, a list of user personas,

representative of the typical customers of the

sneaker store was provided, as well as a list of

typical service failures such as failing to deliver the

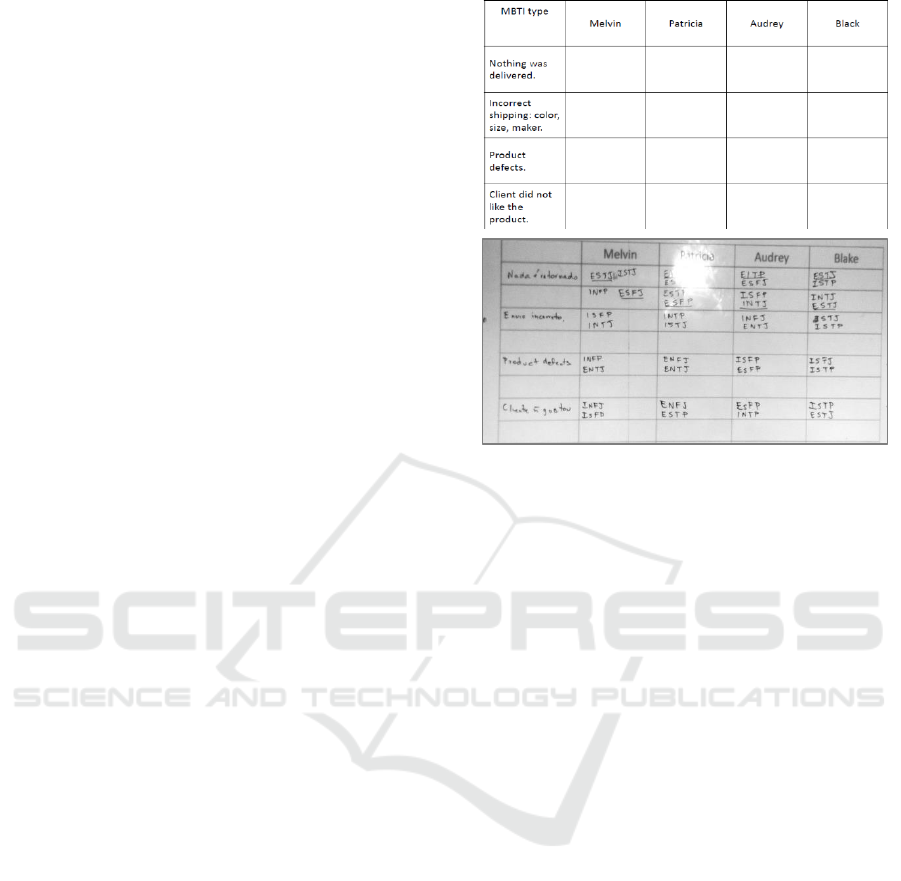

Figure 1: Handout and results of a personality workshop.

product, the product was incorrect or had defects,

etc.

The workshops were conducted in distinct

locations and in different contexts. The first

workshop was executed in a service design school

with about 10 service design students in three

sessions of 4 hours. The other two workshops were

conducted in one day each involving 2 groups of 15

students, mostly from computer science

backgrounds. As mentioned before, the workshop

results are included in this paper only to better

illustrate the design methods proposed and not as

validation of the usefulness or efficacy of the design

methods.

4.1 Personality Workshop

The first of the proposed methods, called personality

workshop, is where designers, potential users, and

stakeholders try to establish the main characteristics

of the personality of the interface persona.

Participants explore individually and in group the

personality traits by using one of the frameworks

discussed earlier. In our workshops, we asked

participants to use the Myers-Briggs framework to

construct the personality of the interface. To

accomplish this, we provided them with a table of

typical service failures as rows and the user personas

as columns, and asked them to explore which MBTI

personality would best work in each case if a human

being was interacting with the user. We then

collected the opinion of everyone on a drawing

board (see Figure 1).

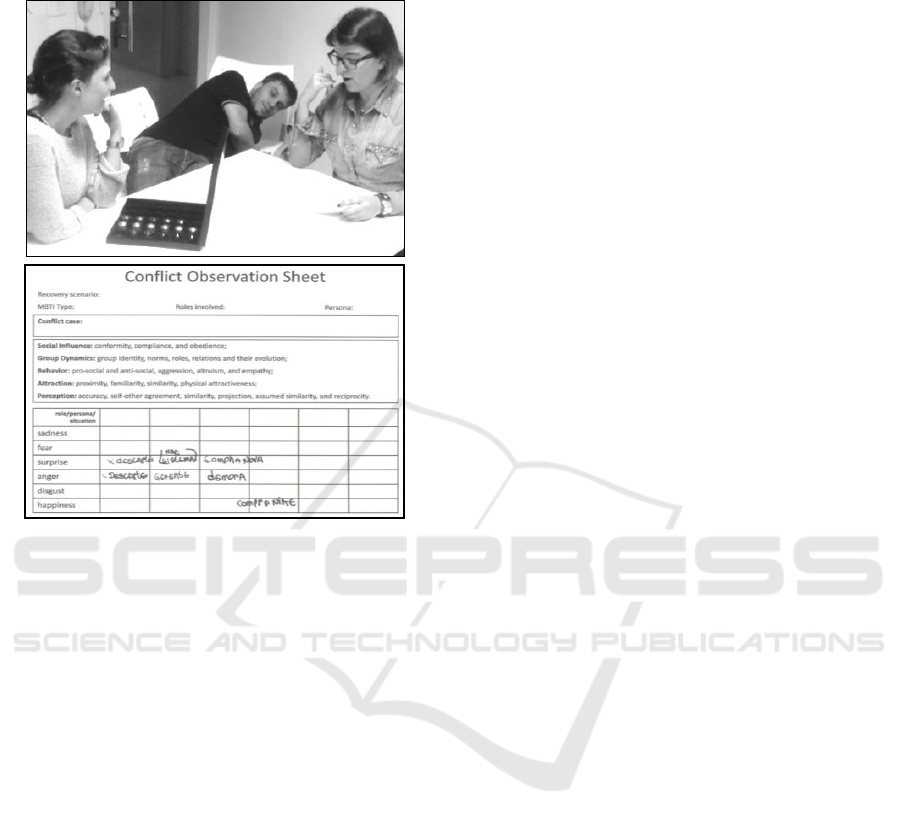

Figure 2: Photo and handout of a conflict battle.

Often, participants in a personality workshop

disagree about the appropriate MBTI for each case

and user persona, what could lead to an interface

persona with multiple personalities. The facilitator

should work on the drawing board to identify the

most common personality types, trying to converge

to a single, most useful personality type which could

handle well most cases and users. In some cases, it

may be necessary to settle for two or more candidate

personalities which can then be explored further

during the rest of the design process. For instance, in

the workshop depicted in Figure 1, participants

preferred an extroverted personality to handle cases

of failed delivery (possible to assertively assure that

a new delivery was scheduled) but considered an

introverted personality as more effective in the case

where the product shipped was incorrect (perhaps to

apologize better for what is a basic mistake).

4.2 Conflict Battle

The second design method we propose juxtaposes a

given personality of the interface persona with the

user personas in specific scenarios of conflict. In this

method, called conflict battle, participants enact

physically a conflict scenario by taking turns playing

the role of the personified interface and the user

personas. This design method employs several

theatrical methods to expose the root causes of the

and to amplify it. It is easier to create better ways to

handle conflicts when all participants understand

their good, band, and ugly components.

The main result of the conflict battle is a series of

conflict skits, short theatrical plays which depict the

social behaviors and emotions involved in actual

conflict scenarios (see Figure 2). We use both

techniques of improv (Johnstone, 1981) and

pantomime (Barba and Savarese, 1991) to foster

theatrical interplay, summarized in the following

“rules of engagement”:

1. Agree (respect what your partner has created).

2. Not only say “Yes.” Say “Yes, and...”.

3. Make statements.

4. There are no mistakes... only opportunities.

5. Exaggerate... and then a little more.

6. React only to what happened.

7. Think aloud to the audience.

Rules 1 to 4 are typical of improvisational theatre

while rules 5 to 7 aim to externalize emotions as

commonly seen in pantomimes. Also, the workshop

facilitator can employ techniques used by theatre

directors such as stopping the action, silencing

temporarily one of the players, switching actors, or

even suggesting possible developments to courses of

action. The goal is to have every skit representing

vigorously the complexity of each conflict scenario.

“Actors” should not take notes or write scripts but

instead “record” in memory the skit as a scene which

can be re-enacted at any moment of the design

process.

While some of the participants are acting out the

scenarios and creating the conflict skits, others take

notes on the conflict observation sheet of the social

behaviors (such as aggression, altruism, empathy)

and the emotions being exhibited by users and the

personified machine (see Figure 2). In our

workshops we employ the standard list of emotions

based on Ekman’s theory (Ekman and Friesen,

1975): happiness, sadness, fear, surprise, anger, and

disgust, and allow observers to include others as

they judge necessary. We also ask participants to

record interpersonal social behaviors related to

social influence, group dynamics, pro- and anti-

social behaviors, attraction, and self-deception.

The conflict battle also explores ways to mitigate

conflicts. After the conflict skits have been

developed and the emotions and social behaviors

discussed, the participants explore variations of the

conflict scenarios where conflict is either reduced or

better resolved. This is accomplished by the

participants re-enacting segments of the conflict

skits using alternative personalities for the

personified interface. For instance, they can try to

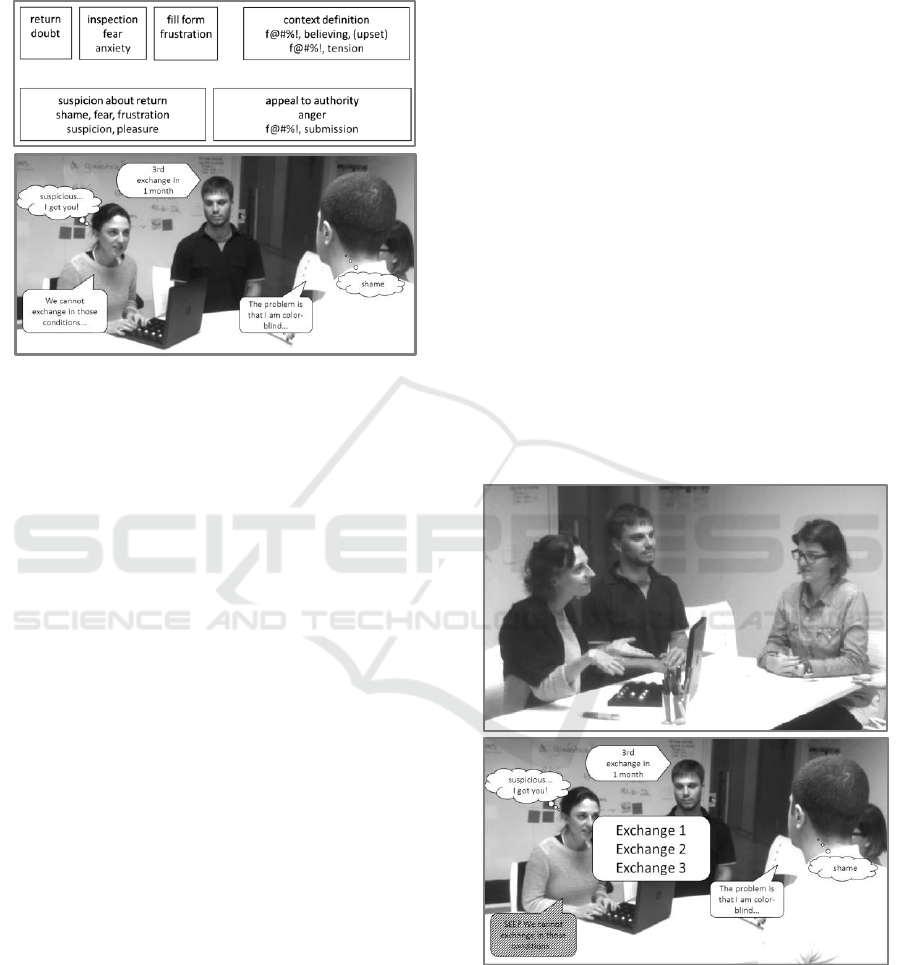

Figure 3: Interaction script and comics storyboard of a

comics workshop.

make the personified machine to be more

subservient, shy, or talkative; and to change the

narrative role the personified machine plays, for

instance, to stop acting as a villain and try to become

a princess in distress.

4.3 Comics Workshop

To better register the results of the conflict battles

we developed a design method using a hybrid

between a comics story (more precisely, a photo

novel) and an interaction storyboard which we call a

comics storyboard. It is an enriched version of the

traditional storyboard used in interface design where

we included photos of the participants enacting the

conflict pantomimes accompanied with typical

markings from comics such as balloons which

explicit the inner thoughts and emotions of the user

and the personified machine (see Figure 3).

As an initial step towards the creation of the

comics storyboard, participants are asked first to

create an annotated interaction script which is a

summary in written form of the main actions of the

corresponding conflict pantomime and their

associated emotions and social behaviors. This script

is used as a guide in the construction of the comics

storyboard to ensure that emotions and social

behaviors are clearly displayed.

The comics storyboards produced in the

workshop are then analyzed in terms of character

consistency, clarity, enjoyment, and quality of

conflict resolution. We found that the production of

the annotated interaction script, prior to the comics

storyboard, is quite helpful in gathering the basic

structure of the pantomime and its main

components. After that, groups or individuals work

separately crafting subsets of the frames of the

comics storyboard. The overall result is a very rich

representation of key aspects of the interaction, its

main conflicts, the characters and subtext of the

narrative, and the emotions and social behaviors

involved.

4.4 Puppet Prototyping

Having explored the range of human exchanges,

emotions, and social behaviors during the conflict

battles and registered them in the comics storyboard

format, the goal of puppet prototyping is to

transform the comics storyboards into concrete

interface actions which can express the mitigating

social behaviors and emotions. For this, participants

go back to the conflict skits they developed and

work using a variety of methods to transform

dialogue and human actions into appropriate

interface actions.

Figure 4: Photo of an action pantomime and an interface

comics.

For this we employ the theatrical action-based

methods of the Stanislavsky’s system, and techniques

from puppetry and movie animation as discussed

before. Using those ideas and principles, participants

are first asked to create action pantomimes, a version

of the conflict skits where emotions and social

behaviors are eventually expressed through interface

actions. They start by re-enacting the conflict skits

using constricted dialoguing techniques. For

example, they act the conflict skits using only very

short sentences, or only gestures, or not facing each

other, or pretending to be animals. The goal is to

explore the limits of human expression to find

mechanisms which convey the social behaviors and

emotions of the conflict skits and their mitigating

solutions. The actions found in the process take the

place of or augment the original dialogue in the

conflict skits and are also recorded in the

corresponding comics storyboard transforming it in

what we call an interface comics (see Figure 4). By

putting them together, participants can then critique

the interface actions considering the human actions,

emotions, and social behaviors they should be

expressing. We then iteratively refine the interface

comics by doing, as necessary, more exploratory

work with constricted dialoguing or by considering

alternative interface actions.

At the end of the puppet prototyping workshop,

the interface comics should contain a complete

interface storyboard to guide the actual

implementation of the interface. Notice that the

interface comics goes further than traditional

storyboards by serving as a documentation also of

the actions, emotions, thoughts, and social behaviors

of the users and of the personified interface.

5 DISCUSSION

This paper presents new methods and techniques to

design personified interfaces and explores their

foundational theoretical frameworks. We argue here

that designing personified interfaces is challenged

by three key requirements: coherent human traits,

dealing with conflict, and handling drama. Inspired

by the service design methodology proposed

in (Pinhanez, 2014), we described and discussed

four design methods to improve the design of the

personified interfaces, illustrated with examples

from three test workshops.

In the test workshops we conducted only

informal debriefs with the participants. The most

common feedback is the surprise on how easily the

design methods revealed and exposed the underlying

conflicts and helped the participants to find ways to

mitigate them. Some initial uneasiness with the

theatrical games and techniques, especially the

constricted dialogue part, was also reported.

There are still many issues and unanswered

questions regarding the proposed design methods.

Our next step is to apply the design methods to real

cases of personified interface design, developing and

deploying the interface, and evaluating how

effective it is in practice.

While we welcome the explosion of chatbots,

mobile assistants, and humanoid robots around us,

we are concerned that there is too much to be

learned too fast to meet the demand of designing

personified interfaces. We hope that some of the

ideas in this paper, although still preliminary and

untested, can serve as a guide for designers facing

the challenge of creating personified interfaces. Our

final goal is to make designers and developers able

to create interfaces in which users can structure their

relationship with personified machines reliably and

consistently, recognizing and appreciating their

personality, engaging in trustable social behaviors,

and co-producing rich, meaningful, and satisfying

interactive drama.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participants of the workshops who

gracefully agreed to allow the use in this paper of

the photos and other materials produced during the

workshops. We thank Heloisa Candello for

references and discussions about designing chatbots.

REFERENCES

Andersen, P. A. and Guerrero, L. K., (1998), Handbook of

Communication and Emotion: Research, Theory,

Applications, and Contexts, Academic Press, San

Diego.

Barba, E. and Savarese, N., (1991), Dictionary of Theatre

Anthropology: The Secret Art of the Performer,

Routledge, London, England.

Blumenthal, E., (2005), Puppetry: a World History, Harry

N. Abrams, Publishers, New York.

Breazeal, C., (2003), "Emotion and Sociable Humanoid

Robots", International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies, 59 (1-2) 119-155.

Campbell, J., (1996), The Hero with a Thousand Faces,

MJF Books, New York.

Dennett, D. C., (1981), "Intentional Systems", in Mind

Design: Philosophy, Psychology, Artificial

Intelligence, (Ed, Haugeland, J.), MIT Press,

Cambridge, Mass., pp. 220-242.

Ekman, P. and Friesen, W. V., (1975), Unmasking the

Face: a Guide to Recognizing Emotions from Facial

Clues, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Giles, H. and Scherer, K. R., (1979), Social markers in

speech, Cambridge,[Eng.]; New York: Cambridge

University Press; Paris: Éditions de la Maison des

sciences de l'homme.

Johnstone, K., (1981), IMPRO: Improvisation and

Theatre, Methuen Drama, England.

Jung, C. G., (1976), Psychological Types, Princeton

University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Laurel, B., (1991), Computers as Theatre, Addison-

Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts.

Lee, E. J., (2003), "Effects of “gender” of the computer on

informational social influence: the moderating role of

task type", Internation Journal of Human-Computer

Studies, 58 (4) 347-362.

Lee, E. J., Nass, C. and Brave, S., (2000), in CHI '00

Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, The Hague, The Netherlands, pp. 289-290.

Lewin, K. and Gold, M., (1999), The Complete Social

Scientist : a Kurt Lewin Reader, American

Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Li, J., Ju, W. and Reeves, B., (2016), in 66th Annual

Conference of the International Communication

Association, Fukuoka, Japan.

Luger, E. and Sellen, A., (2016), in Proceedings of the

2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, Santa Clara, California, USA, pp.

5286-5297.

Myers, I. B., (1998), MBTI Manual: a Guide to the

Development and Use of the Myers-Briggs Type

Indicator, Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto,

California.

Nass, C. and Lee, K. M., (2001), "Does computer-

synthesized speech manifest personality?

Experimental tests of recognition, similarity-attraction,

and consistency-attraction", Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Applied, 7 (3) 171.

Nass, C. and Najmi, S., (2002), Paper submitted to CHI

2002.

Nass, C., Takayama, L. and Brave, S., (2006), "Socializing

Consistency", in Human-Computer Interaction and

Management Information Systems: Foundations, (Eds.

Zhang, P. and Galleta, D. F.), ME Sharpe, pp. 373-

391.

Nass, C. I. and Brave, S., (2005), Wired for Speech: How

Voice Activates and Advances the Human-Computer

Relationship, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Newman, M. L., Groom, C. J., Handelman, L. D. and

Pennebaker, J. W., (2008), "Gender Differences in

Language Use: An Analysis of 14,000 Text Samples",

Discourse Processes, 45 (3) 211-236.

Norman, W. T., (1963), "Toward an adequate taxonomy of

personality attributes: Replicated factor structure in

peer nomination personality ratings.", Journal of

Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66 574-583.

Pinhanez, C., (2014), in Proc. of 4th Service Design and

Service Innovation Conference, Lancaster, UK, April

9-11, pp. 100-109.

Plutchik, R., (1980), Emotion: A psychoevolutionary

synthesis, Harpercollins College Division.

Propp, V., (1968), Morphology of the Folktale, University

of Texas Press, Austin.

Pruitt, J. and Adlin, T., (2006), The Persona Lifecycle:

Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design,

Elsevier : Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, an imprint of

Elsevier, Amsterdam ; Boston.

Reeves, B. and Nass, C., (1996), The Media Equation:

How People Treat Computers, Television, and New

Media like Real People and Places, CSLI, Stanford,

California.

Stanislavsky, C., (1949), Building a Character,

Routledge/Theater Arts Books, New York.

Tajfel, H., (1974), "Social identity and intergroup

behaviour", Social Science Information/sur les

sciences sociales, 13 (2) 65-93.

Tajfel, H., (1981), Human Groups and Social Categories:

Studies in Social Psychology, Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge, England.

Thomas, F. and Johnston, O., (1981), Disney Animation:

The Illusion of Life, Abbeville Press, New York.

Vogler, C., (2007), The Writer's Journey: Mythic

Structure for Writers, Michael Wiese Productions,

Studio City, CA.