A Framework for Small Group Support in Online Collaborative

Learning

Combining Collaboration Scripts and Online Tutoring

Aleksandra Lazareva

Department of Global Development and Planning, University of Agder, Gimlemoen 25, Kristiansand, Norway

Keywords: Computer-supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL), Collaboration Scripts, Online Tutoring, Learning

Management System (LMS), Technology-mediated Learning (TML) Model.

Abstract: Many learners experience difficulties engaging in collaborative learning activities online. Computer-

supported collaborative learning (CSCL) scripts have been implemented to support online learners.

Collaboration scripts have shown much potential in facilitating students’ general collaboration skills.

However, reported effects of collaboration scripts on domain-specific knowledge acquisition have been less

positive. In this paper, I suggest an alternative framework for supporting CSCL learners by combining

collaboration scripting and online tutoring. While collaboration scripts can facilitate the acquisition of

general collaboration skills, the online tutor is capable of monitoring and assessing small groups’ progress

and providing them with suitable content-specific prompts. The role of the online tutor is also important in

terms of establishing social presence in the online learning environment. In order to develop the conceptual

framework, I present experiences from an online collaborative learning course. I support the discussion by

student insights collected through surveys and a focus group interview.

1 INTRODUCTION

Collaborative learning is a result of a continued

attempt to reach and maintain a shared

understanding of a concept (Roschelle and Teasley,

1995). Collaboration may happen spontaneously, but

usually this is not the case (Strijbos, Martens, and

Jochems, 2004). Lack of prior knowledge about

collaboration makes it challenging for students to

engage in crucial processes of an effective

collaboration setting (Fischer et al., 2013).

In addition to predicting the interaction and

impact of multiple factors in a computer-supported

collaborative learning (CSCL) environment,

researchers attempt to directly influence the flow of

collaborative learning (Dillenbourg, 2002), by

providing specific support. Kopp et al., (2012)

specify that there are two methods to support online

collaborative activities: providing certain structures

in the learning environments or moderating the

collaborative learning process during the process

itself. An example of the former is CSCL scripts,

and of the latter – online tutoring. Collaboration

scripting has shown much potential in facilitating

interactions among learners. However, there is a

number of unsolved challenges in relation to the

design and implementation of collaboration scripts.

This paper presents a framework for small group

support in CSCL contexts that combines CSCL

scripting and online tutoring.

The paper reports on 2,5 years of experience

from a tutor-supported online collaborative learning

course. The paper presents a holistic view of the

CSCL environment created, and discusses how the

learner support functions in this. The discussion is

complemented with data collected through student

surveys and interviews. Thus, the paper seeks to

address the following question: How can CSCL

scripting and online tutoring be combined to provide

small groups with support for cognitive, meta-

cognitive, and social processes?

The paper is structured as follows. The next

section discusses related literature, followed by an

outline of the methods applied for the empirical

research. Next, the experiences from the online

collaborative learning course are presented. The

preliminary framework for learner support is

discussed. The final section presents conclusions and

implications for future research.

Lazareva, A.

A Framework for Small Group Support in Online Collaborative Learning - Combining Collaboration Scripts and Online Tutoring.

DOI: 10.5220/0006325802550262

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 2, pages 255-262

ISBN: 978-989-758-240-0

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

255

2 RELATED RESEARCH

A collaboration script is a “set of instructions

prescribing how students should form groups, how

they should interact and collaborate and how they

should solve the problem” (Dillenbourg, 2002, p.

61). A variety of collaboration scripts and their key

functions have been discussed in the literature

(Dillenbourg, 2002; Kobbe et al., 2007; Kollar et al.,

2006; Weinberger, 2011). Collaboration scripts can

be introduced in both face-to-face and computer-

mediated conditions (“CSCL scripts”).

A recent meta-analysis by Vogel et al., (2016)

demonstrates that collaboration scripts have a strong

positive effect on collaboration skills, but a small

effect on domain-specific knowledge acquisition.

Studies have reported on absent or even negative

effects of scripting on domain-specific knowledge

acquisition (Stegmann et al., 2007; Weinberger et

al., 2005). It has been demonstrated how a script can

limit learners’ reflective thinking (Weinberger et al.,

2005). Providing too much structure can also lead to

learners choosing not to follow the script due to the

cognitive load (Popov et al., 2014).

Instead of imposing a lot of structure on

learners’ activities, scripts can be particularly

effective when they promote knowledge about

argumentation (Noroozi et al., 2013).

The effectiveness of collaboration scripts has

also been found to depend on learners’ internal

scripts, that is, their prior knowledge on

collaboration (Kollar et al., 2006; Kollar et al.,

2007). The adaptive way of scripting has been

discussed as the optimal solution – fading the script

out over time or providing scripting only when

necessary (Rummel et al., 2009). Fading would be

optimal in case it is “adapted to the learner’s current

state of development of internal script components”

(Fischer et al., 2013, p. 63). Therefore, in order to

provide an adequate level of scaffolding, it is

necessary to evaluate learners’ current needs.

Online tutoring is another way to provide

support to online students. Normally, tutors do not

really teach; instead, they guide students through the

activities planned by the course teacher (Goold et

al., 2010).

Berge (1995) categorizes a tutor’s tasks into

pedagogical, social, managerial and technical.

Kopp et al., (2012) mention three large groups of

collaborative learning activities which need to be

supported by the online tutors: content-specific

cognitive activities, social activities, and meta-

cognitive activities. These classifications can be

viewed together (see Table 1).

In this paper, I aim to explore the potential of

combining collaboration scripts and online tutoring

in order to ensure sufficient and adaptive support for

CSCL learners.

Table 1: Roles of the online tutor aimed at supporting

content-specific cognitive, social and meta-cognitive

collaborative learning activities.

Role

(Berge, 1995)

Supported

processes

(Kopp et al., 2012)

Examples

Pedagogical

Content-specific

cognitive

Monitor progress;

provide feedback and

prompts

Social

Social

Promote open and

inclusive learning

environment

Managerial

Meta-cognitive

Help students plan and

coordinate activities

Technical

3 METHOD

In order to develop a conceptual framework for

small group support in a CSCL environment, I

discuss observations from an online collaborative

learning course through the lens of the technology-

mediated learning (TML) model (Gupta and

Bostrom, 2009). I support the discussion by insights

from student surveys and a focus group interview.

3.1 Course and Participants

The context is a one-year postgraduate online

collaborative learning course run by a Norwegian

university. The course focuses on online pedagogy

and design of online courses. By February 2017, two

cohorts have completed the course (N=54) and the

third cohort (N=24) is currently taking the course.

The course is international and has involved

participants from Europe, central Africa, Asia, and

Latin America. Educational background and age of

the participants also vary. As the course is targeted

at specific groups in partner universities, some of the

participants may be familiar with each other before

starting the course. In addition, there is a one-day

face-to-face kick-off session organized locally for

groups located in Norway and central Africa.

The scope of the course is 20 ECTS credits.

Students are assigned in small (5-6 members) cross-

cultural groups where they work throughout the

semester. The first cohort was not facilitated by the

online tutor. The online tutor support was introduced

in the second round of the course, and the author of

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

256

the paper has been involved in this role up to the

present moment. Implementation of collaboration

scripts in the course is discussed in Section 4.3.2.

The main learning platform is a university

learning management system (LMS) with standard

functionality.

3.2 Student Perspective

In this paper student insights are used in order to

build a comprehensive framework for learner

support in CSCL. Student insights were collected

from representatives of all three cohorts:

Student survey of the 2

nd

cohort administered in

the end of fall semester 2015 (N=14);

Focus group interview with African participants

from the 1

st

and 2

nd

cohorts carried out in the end

of spring semester 2016 (N=14);

Student survey of the 3

rd

cohort administered at

the start of spring semester 2017 (N=9).

Selected excerpts from the surveys and the interview

are included in the paper in order to complement the

observations.

3.3 TML Model

The experiences from the online collaborative

course and the results of the empirical data

collection are presented based on the TML model

(Gupta and Bostrom, 2009). The model is based on

two premises. First, external structures are designed

to reflect the spirit of the system (i.e., the specific

way of how the participants are expected to act).

Second, the participants (i.e., learners) interact with

the system and adapt its features according to their

interpretation of the spirit. Importantly, the TML

model focuses on the learning process, during which

the students are expected to appropriate the

structures.

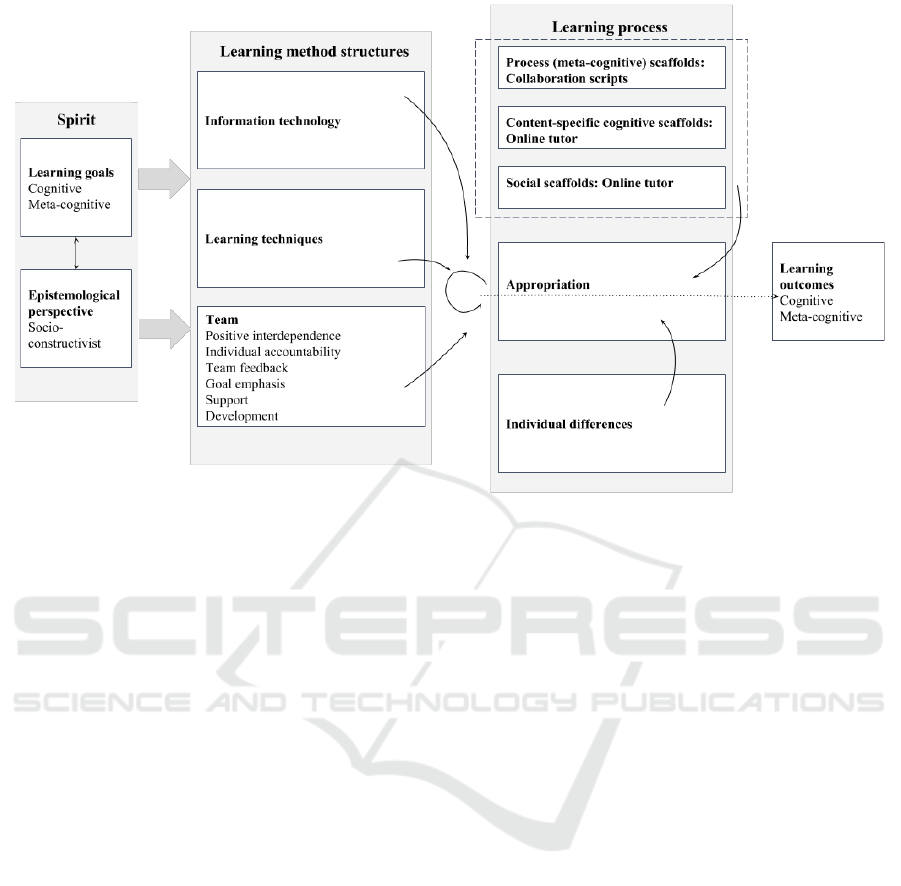

The model is used in the paper as a lens for

understanding the interplay of core elements in a

CSCL environment holistically. In the next section, I

discuss each of these elements, following the

propositions of the TML model and referring to the

experiences from our course. Most attention is

focused around the learning process and support

mechanisms integrated in this (see Figure 1).

4 EXPERIENCES FROM THE

COURSE

4.1 Spirit

The spirit of the system is driven by the learning

goals and epistemological perspectives (Gupta and

Bostrom, 2009). The epistemological perspective of

the collaborative learning course discussed in the

paper is socio-constructivist, where learners are

active in advancing their knowledge through the

shared processes of discussion and argumentation.

Meta-cognitive learning goals become as important

as cognitive goals, since students are expected to

learn to reflect, question and argument in addition to

obtaining content-specific knowledge.

4.2 Learning Method Structures

The structures are implemented in the learning

method dimension, which includes the aspects of

information technology, learning techniques and

team (Gupta and Bostrom, 2009).

4.2.1 Information Technology

Jeong and Hmelo-Silver (2016) have identified

seven core affordances of technology to support

collaborative learning. Collaborative technologies

should allow students to (1) engage in a joint task,

(2) communicate, (3) share resources, (4) engage in

productive collaborative learning processes, (5)

engage in co-construction, (6) monitor and regulate

collaborative learning, and (7) find and build groups

and communities.

The LMS has proved to be an appropriate

technology for online collaboration. Students

actively use the platform to work collaboratively.

All discussions in the LMS run asynchronously by

means of text. The asynchronous mode of

communication ensures flexibility for students from

different parts of the world to participate, which is

crucial in this context. Moreover, asynchronous

discussions make learning visible and help students

reflect (Serçe et al., 2011).

However, some student feedback has also

suggested that synchronous channels for

communication need to be provided to some extent:

“We never had a clear time we could discuss more

synchronously” (survey of the 2

nd

cohort).

A Framework for Small Group Support in Online Collaborative Learning - Combining Collaboration Scripts and Online Tutoring

257

Figure 1: Small group support framework (dashed line) in the context of the TML model (Gupta and Bostrom, 2009).

4.2.2 Learning Techniques

CSCL courses often deal with fuzzy learning

techniques which encourage the learners to explore,

discuss and negotiate with each other, which is also

the case in the course discussed in this paper.

Constructing meaningful tasks having variant

solutions is crucial for learners to have a productive

collaborative discussion.

4.2.3 Team

The team dimension in the TML model includes

several components which are especially important

in collaborative learning.

Positive interdependence refers to each group

member not being able to succeed unless the other

team members succeed. This way, each peer’s

contribution benefits the rest of the group (and vice

versa) (Kreijns et al., 2003). I have observed that

positive interdependence may not have been

promoted sufficiently in our course environment, as

a large part of the assessed work is done

individually.

Individual accountability refers to each of the

group members being responsible for doing his or

her share of the common task (Kreijns et al., 2003).

One of the problems in the CSCL context is that the

external observer (i.e., tutor) does not always have

the full overview of the group’s activity. While it is

possible to provide feedback to the group,

identifying the contribution of individual

participants becomes challenging.

Team feedback refers to students reflecting on

how well the team is performing (Gupta and

Bostrom, 2009). In the course discussed in this

paper, participants are encouraged to share

reflections after completion of each module on their

group’s forum. These reflections concern individual

and group learning processes.

Goal emphasis refers to students focusing on

accomplishing team goals (Gupta and Bostrom,

2009). An effective strategy used in this course is

the “group contract” which students are required to

agree upon in the beginning of the process. A

standard template of the contract can guide students

in specifying the aspects necessary for successful

collaboration. Goal emphasis is crucial for students

in building a common ground before starting the

collaborative process. Students commented on the

usefulness of the group contract in the surveys and

interview, for example, “The group contract that we

made at the beginning of the course helped us to

work together” (survey of the 2

nd

cohort).

The support and development refer to promoting

students’ understanding and sustaining effective

interactions respectively (Gupta and Bostrom, 2009).

In collaborative learning, students prompt each other

and build on each other’s understanding in order to

advance their knowledge. In addition to acquiring

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

258

content-specific knowledge, students need to be able

to argument, discuss and negotiate. While some of

the participants may have more advanced

collaboration skills, other members may require

more support and scaffolding. I focus on the support

techniques in the next section.

4.3 Learning Process

During the learning process students are expected to

actually appropriate the learning method structures.

According to the TML model, learning process

includes appropriation, process scaffolds, and

individual differences (Gupta and Bostrom, 2009). I

complement the framework with content-specific

cognitive scaffolds and social scaffolds.

4.3.1 Appropriation

If structures are well-designed, better appropriation

is expected to lead to better learning outcomes

(Gupta and Bostrom, 2009).

In this course, the structures have generally been

appropriated the way it was expected. Student

groups settle with the shared understanding of how

the tools are to be used. However, the results of the

focus group interview reveal that students

sometimes had to switch to alternative

communication channels due to the access issues.

Moreover, the focus group interview revealed

that a significant number of participants had felt

uncomfortable as they had experienced challenges

when navigating in the LMS in the beginning of the

course. These participants confessed that if not for

the help of their peers and tutors, they would have

most likely given up at the early stages of the course.

4.3.2 Process Scaffolds

If the learning method has well-designed structures,

scaffolds will influence the faithfulness of learning

method appropriation. According to the TML model,

appropriation of the learning method structures is

facilitated by the meta-cognitive (i.e., promoting

individual reflection on learning), procedural (i.e.,

promoting effective use of available resources and

tools), and strategic (i.e., helping students plan and

analyze) scaffolds (Gupta and Bostrom, 2009).

I have observed that scaffolding is important on

both macro (i.e., the course) and micro (i.e., the task)

levels. In this course, scaffolding on the macro level

is implemented through a detailed overview of the

course structure. Such scaffolding fosters students’

awareness as they have a clear idea of how the roles

will be rotated and activities distributed throughout

the course (Weinberger, 2011). Tutorials on the use

of the tools are provided in the course environment.

Scaffolding on the task level was not provided

for the first two cohorts. I then observed that

participation in the beginning of the course was

rather limited as students seemed insecure about the

necessary steps to be taken and their timing. It also

took time for the tutor to evaluate students’ levels of

participation to provide prompts. Moreover,

throughout the course students often spent too much

time (even with tutor’s intervention) on specifying

their course of action. The collaboration scripts were

implemented in selected activities for the latest

cohort. Collaboration scripts facilitated role division,

and students generated more questions to peers

aimed at building shared understanding of concepts.

In addition, they had a clearer course of action and

the overall amount of coordination was reduced.

4.3.3 Content-specific Cognitive Scaffolds

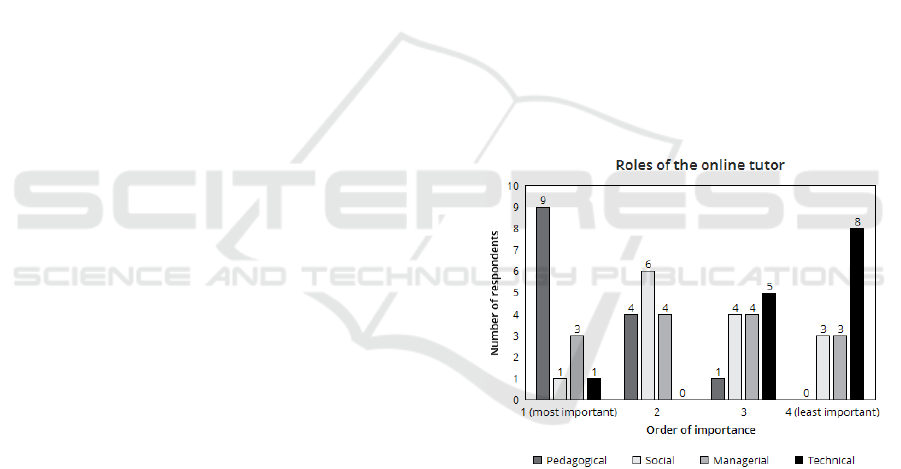

In the survey of the 2

nd

cohort, the students were

asked to rank the four roles of the online tutor

(Berge, 1995) in order of importance for them (see

Figure 2).

Figure 2: Roles of the online tutor ranked by students.

The pedagogical role was considered most

important, which emphasizes the importance of tutor

participation in the process of content-specific

knowledge acquisition.

In addition, students from the 2

nd

cohort were

also asked to choose from one to five specific

functions of the online tutor which they experienced

as most beneficial for them (also the “other” option

was provided, but was not chosen) (see Table 2).

The most frequently chosen options demonstrate that

students especially appreciated the pedagogical and

managerial role of the tutor.

A Framework for Small Group Support in Online Collaborative Learning - Combining Collaboration Scripts and Online Tutoring

259

Table 2: Students’ responses about tutor’s functions (“P” –

Pedagogical, “S” – Social, “M” – Managerial, “T” –

Technical).

Functions

Role

N

Explaining aspects of the course content

P

9

Providing additional materials

P

8

Pointing out the areas for improvement

P

7

Providing feedback after the task

completion

P

7

Providing guiding questions

P

4

Providing individual support

P

2

Encouraging your participation

S

6

Acknowledging your work

S

3

Promoting social interactions

S

2

Helping to handle conflicts in the group

S

0

Guiding you through the course structure

and assignment requirements

M

9

Reminding you of the deadlines

M

2

Helping you to use the technology

T

1

Too much tutor intervention may result in students

only addressing the tutor’s requests instead of

developing their own line of discussion (An et al.,

2009). I have observed students having different

opinions about the frequency of tutor’s

interventions. For example, the survey of the 3

rd

cohort suggests that the cohort is somewhat less

dependent on the online tutor’s involvement

(possibly due to a higher number of students having

experience in online collaborative learning).

4.3.4 Social Scaffolds

Reflecting on earlier research (Kopp et al., 2012;

Remesal and Colomina, 2013; Sung and Mayer,

2012), it is crucial to include social processes as one

of the learning process dimensions in CSCL.

Learners should be able to share opinions freely in

order to relate to and benefit from each other’s

knowledge. Online tutoring has been demonstrated

to be able to promote social presence (Lazareva,

2017; Sung and Mayer, 2012).

Generally, the students perceive the course

environment as open and supportive: “I felt that my

views were never ridiculed at any time, so it made

me free to say whatever I wanted to say” (survey of

the 2

nd

cohort); “[…] all members were very

courteous and civil to one another” (survey of the

3

rd

cohort). However, it was also mentioned that

there was little personal communication in the

platform: “My group interactions were strictly on

the academic discussions we were meant to handle.

There was very little sharing of personal experiences

and it was too little for me to learn about my peers

or my tutor” (survey of the 2

nd

cohort).

4.4 Individual Differences

Last but not least, it is important to mention that

individual differences can influence learning

outcomes by affecting the faithfulness of learning

method appropriation (Gupta and Bostrom, 2009).

Although multiple aspects can be discussed in this

section, I will underline two of them: (1) cultural

background and (2) previous experience in online

collaborative learning.

Generally, students have been reporting positive

experiences regarding the cross-cultural

collaboration as they have perceived it as enriching.

However, some of the students have reported on

differences in approaching the tasks, for example:

“[…] while we would initiate a conversation about a

topic by conveying our own thoughts and feelings on

a subject, very often they would write a big article

about the subject where they talk about the views of

other people on this subject, complete with a list of

references” (survey of the 3

rd

cohort).

I have also observed how differences among

students in terms of experience in online

collaborative learning have influenced the quantity

and quality of participation in discussion forums.

Naturally, experienced learners are more proactive

and master the features of the LMS more efficiently.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Outlining the Framework

Synthesizing research on online tutoring and CSCL

scripting and complementing it with our experiences

from running an online collaborative learning course

made it possible to suggest a framework for small

group support in the CSCL setting (see Figure 1).

The framework addresses facilitation of content-

specific cognitive, meta-cognitive and social

learning processes in students. The TML model

(Gupta and Bostrom, 2009) used as a lens to develop

the framework considers the interplay of crucial

dimensions in a CSCL environment as a whole. It is

important to ensure that all the elements are present.

If not, this may impede the collaborative learning

process in ways that cannot be effectively addressed

by the online tutor or collaboration scripts.

Meta-cognitive learning processes can be

facilitated by CSCL scripts. Instruction by scripts

implies specific behavior from students. The scripts

here make concrete prompts on how to act and take

care of role rotation to ensure equal participation.

Scripts also help students reduce process losses by

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

260

grouping them, distributing tasks among the group

members and setting the time frames. Too much

effort paid to the coordination activities may impede

the socio-cognitive processes (Weinberger, 2011).

Scripts decrease students’ uncertainty about the

organization of the course in general, procedures in

separate tasks and use of the tools.

However, as Vogel et al., (2016) discuss,

students acquire effective collaborative learning

skills when they are repeatedly supported by scripts

so that they have time to internalize effective

strategies.

Content-specific cognitive processes can be

scaffolded by the online tutor. Students’ different

opinions on the amount of tutor interventions

underline the importance of support being adaptive.

It is vital for the tutor to monitor how much support

students need to provide appropriate scaffolding.

A positive social atmosphere is an important

aspect in effective CSCL, which should not be taken

for granted. In online environments students may

experience lack of social connection with each other

due to the text-based nature of communication (Sung

and Mayer, 2012). The online tutor can help students

avoid the feeling of loneliness in an online

environment (Kopp et al., 2012). The social role of

the tutor is therefore included into the framework.

Relatively small amount of survey and interview

respondents is the main limitation of this paper.

However, I have considered student reflections from

each of the three cohorts to create a wider picture of

the course design, its advantages and drawbacks.

5.2 Implications for Further

Improvement of the CSCL

Environment

Reporting on the course experiences through the

TML model makes it possible to reflect on

implications for further improvement:

Complementing the asynchronous learning

environment with opportunities for synchronous

communication may be beneficial. This would

also facilitate more off-task interactions (Serçe et

al., 2011);

More emphasis should be put on the group

dimensions (as opposed to individual) in order to

enhance positive interdependence;

Implementing peer assessment techniques may

be helpful in order to ensure individual

accountability;

Implementing collaboration scripts should start

from the very beginning of the course and allow

students to gradually internalize the effective

strategies.

Moreover, the role of peers and tutors should not be

underestimated in the beginning of the course when

the online environment is being introduced. Many

novice participants may require additional guidance.

6 CONCLUDING REMARKS

The paper has discussed an approach for combining

collaboration scripting and online tutoring in the

overall design of a CSCL course in order to ensure

support for learning processes in small groups. This

approach is transferable to similar contexts and does

not require specific software for its implementation.

The discussion also signals several areas where

work remains to be done, such as facilitating

collaborative interactions across cultures and

developing assessment techniques that would ensure

positive interdependence and individual

accountability.

It has previously been questioned whether

experienced tutors develop their approach based on

daily practice or whether they have a theoretical

basis for more profound reflection (Kopp et al.,

2012). Developing a more systematic view on

providing content-specific and social scaffolds is

important in order to introduce concrete guidelines

for online tutors. In the same way, future research

should look into guidelines for educators in terms of

designing collaboration scripts to support meta-

cognitive learning processes in small groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the research participants for

their valuable input, and my supervisors Bjørn Erik

Munkvold and Oddgeir Tveiten for their guidance

and comments on the paper.

REFERENCES

An, H., Shin, S., Lim, K., 2009. The effects of different

instructor facilitation approaches on students’

interactions during asynchronous online discussions.

Computers & Education, 53, 749-760.

Berge, Z. L., 1995. Facilitating computer conferencing:

Recommendations from the field. Educational

Technology, 35, 22-30.

Dillenbourg, P., 2002. Over-scripting CSCL: The risks of

blending collaborative learning with instructional

A Framework for Small Group Support in Online Collaborative Learning - Combining Collaboration Scripts and Online Tutoring

261

design. In P. A. Kirschner (ed.), Three worlds of

CSCL. Can we support CSCL? (pp. 61-91). Open

Universiteit Nederland, Heerlen.

Fischer, F., Kollar, I., Stegmann, K., Wecker, C., 2013.

Toward a script theory of guidance in computer-

supported collaborative learning. Educational

Psychologist, 48, 56-66.

Goold, A., Coldwell, J., Craig, A., 2010. An examination

of the role of the e-tutor. Australasian Journal of

Educational Technology, 26, 704-716.

Gupta, S., Bostrom, R.P., 2009. Technology-mediated

learning: A comprehensive theoretical model. Journal

of the Association for Information Systems, 10, 686-

714.

Jeong, H., Hmelo-Silver, C. E., 2016. Seven affordances

of computer-supported collaborative learning: How to

support collaborative learning? How can technologies

help? Educational Psychologist, 51, 247-265.

Kobbe, L., Weinberger, A., Dillenbourg, P., Harrer, A.,

Hämäläinen, R., Häkkinen, P., Fischer, F., 2007.

Specifying computer-supported collaboration scripts.

Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 2, 211-

224.

Kollar, I., Fischer, F., Hesse, F.W., 2006. Collaboration

scripts – A conceptual analysis. Educational

Psychology Review, 18, 159-185.

Kollar, I., Fischer, F., Slotta, J.D., 2007. Internal and

external scripts in computer-supported collaborative

inquiry learning. Learning and Instruction, 17, 708-

721.

Kopp, B., Matteucci, M. C., Tomasetto, C., 2012. E-

tutorial support for collaborative online learning: An

explorative study on experienced and inexperienced e-

tutors. Computers & Education, 58, 12-20.

Kreijns, K., Kirschner, P.A., Jochems, W., 2003.

Identifying the pitfalls for social interaction in

computer-supported collaborative learning

environments: A review of the research. Computers in

Human Behavior, 19, 335-353.

Lazareva, A., 2017. Role of the online tutor in establishing

the social presence in asynchronous text-based

collaborative learning environments. In M. E. Auer, D.

Guralnick, J. Uhomoibhi (eds.), Interactive

Collaborative Learning (pp. 128-142). Springer

International Publishing.

Noroozi, O., Weinberger, A., Biemans, H. J. A., Mulder,

M., Chizari, M., 2013. Facilitating argumentative

knowledge construction through a transactive

discussion script in CSCL. Computers & Education,

61, 59-76.

Popov, V., Biemans, H.J.A., Kuznetsov, A.N., Mulder,

M., 2014. Use of an interculturally enriched

collaboration script in computer-supported

collaborative learning in higher education.

Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 23, 349-374.

Remesal, A., Colomina, R., 2013. Social presence and

online collaborative small group work: A

socioconstructivist account. Computers & Education,

60, 357-367.

Roschelle, J., Teasley, S.D., 1995. The construction of

shared knowledge in collaborative problem solving. In

Computer supported collaborative learning (pp. 69-

97). Springer, Heidelberg.

Rummel, N., Spada, H., Hauser, S., 2009. Learning to

collaborate while being scripted or by observing a

model. Computer-supported Collaborative Learning,

4, 69-92.

Serçe, F.C., Swigger, K., Alpaslan, F.N., Brazile, R.,

Dafoulas, G., Lopez, V., 2011. Online collaboration:

Collaborative behavior patterns and factors affecting

globally distributed team performance. Computers in

Human Behavior, 27, 490-503.

Stegmann, K., Weinberger, A., Fischer, F., 2007.

Facilitating argumentative knowledge construction

with computer-supported collaboration scripts.

International Journal of Computer-Supported

Collaborative Learning, 2, 421-447.

Strijbos, J.-W., Martens, R.L., Jochems, W.M.G., 2004.

Designing for interaction: Six steps to designing

computer-supported group-based learning. Computers

& Education, 42, 403-424.

Sung, E., Mayer, R.E., 2012. Five facets of social presence

in online distance education. Computers in Human

Behavior, 28, 1738-1747.

Vogel, F., Wecker, C., Kollar, I., Fischer, F., 2016. Socio-

cognitive scaffolding with computer-supported

collaboration scripts: A meta-analysis. Educational

Psychology Review, 1-35.

Weinberger, A., 2011. Principles of transactive computer-

supported collaboration scripts. Nordic Journal of

Digital Literacy, 6, 189-202.

Weinberger, A., Ertl, B., Fischer, F., Mandl, H., 2005.

Epistemic and social scripts in computer-supported

collaborative learning. Instructional Science, 33, 1-30.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

262