Interaction Patterns in Web-based Knowledge Communities:

Two-Mode Network Approach

Wouter Vollenbroek and Sjoerd de Vries

Behavioural Sciences, University of Twente, Drienerlolaan 5, Enschede, Netherlands

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Lifelong Learning, Social Network Analysis, Web-based Knowledge

Communities.

Abstract: The importance of web-based knowledge communities (WKCs) in the 'network society' is growing. This trend

is seen in many disciplines, like education, government, finance and other profit- and non-profit organisations.

There is a need for understanding the development of these online communities in order to steer it and to

affect the impact it has. In this research, we aimed to identify interaction patterns in these communities to

visualize and understand community developments, and show the relevance of WKCs for the development of

learning education. We conducted a content analysis and a network analysis on big social data to identify the

patterns in two Facebook-groups which were focused on educational development. Analysis of interaction

patterns enabled us to identify three interaction stages within WKCs in educational settings: introduction,

evolution and maturity. In the first stage, participants mainly introduce themselves. In the second stage, one

shares information and in the final stage, participants are more open to share their opinions. The study shows

that our network analysis approach is appropriate to analyse and visualize the development of interaction

patterns and the results could help us to steer communities effectively and efficiently.

1 INTRODUCTION

Individual and collective professionalization is

already a hot topic for decades (e.g. Sheng and Yao,

2004; Windahl and Rosengren, 1978). As Chugh

(2015) has indicated, there is – in our contemporary

society – still an enormous need for ways to create

and exchange tacit knowledge. One is thus still

looking for the holy grail concerning the successful

development of cooperative professional learning

practices. Multiple initiatives were taken to stimulate

this, some examples are communities of practice,

teams, and physical meetings. But the technological

advances has accelerated the developments in the way

we communicate, collaborate and share our

knowledge with others, this has resulted in a way of

working which is more efficient and effective and

which reaches a larger audience. The result is a

dramatically growing number of professionals who

share their resources, develop (new) working

strategies, solve (existing) problems, and improve the

individual-, the communal- and the organisational

performance (Tseng and Kuo, 2014). Web-based

knowledge communities (WKCs) exemplifies such

continuous professional development mechanisms. A

WKC is “a community that allows individuals to seek

and share knowledge through a website based on

common interests” (Lin et al, 2007). Especially in

educational institutions is the relevance of web-based

knowledge communities recognized by for example

teachers, pedagogics and instructional designers.

These professionals use it to improve their own

knowledge and skills, but also to realize a situation of

continuous educational development. In order to put

WKCs into perspective, we use the concept of

learning education. This phenomenon is defined as

“the learning landscape that facilitates the learning of

all its members within open educational networks and

continuously transforms itself in order to meet its

strategic goals by using the latest online

developments” (Vollenbroek et al, 2014). A learning

landscape consists of different elements and

professional learning practices, such as courses,

conferences, regulations and the web-based

knowledge communities.

In this study, we focus on the development of

web-based knowledge communities. Since these

online spots develop reasonable unstructured, it is

important to visualize and analyse it. In this study, we

make a first attempt by analysing interaction patterns

100

Vollenbroek, W. and Vries, S.

Interaction Patterns in Web-based Knowledge Communities: Two-Mode Network Approach.

DOI: 10.5220/0006035701000107

In Proceedings of the 8th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2016) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 100-107

ISBN: 978-989-758-203-5

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

and visualizing it by the two-mode network approach.

Interaction patterns represent the genre which

activates individuals to perform in a certain manner.

This leads to the following research question

which is central to this article: “What kind of

interaction patterns describe the development of an

online web-based knowledge community in an

educational context?” An answer to this research

question helps us to define the development of WKCs

based on interaction patterns and can be used to

monitor and steer the community development.

Furthermore, the method of analysis and visualization

of this development improves our methodological

understanding of approaches to analyse and visualise

these patterns.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this article, we analyse two specific professional

development cases which are embodied as web-based

knowledge communities. To describe these cases, we

have decided to use a mixed evaluation method,

which includes content analysis and network analysis

(SNA). The Excel-plugin NodeXL is used to

download and convert the data, and Gephi is used to

visualize and analyse it. The first case embodies an

interactive Facebook Group which belongs to a

Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), due to

privacy-issues we call this WKC: “Community of

Learning Innovation”. The second case is a Facebook

Group for the professional linguistic development of

individuals, we call this WKC: “Community of

Linguistic Innovation”. Initially the Community of

Learning Innovation is aimed as a discussion

environment for participants in the MOOC, this group

has for that reason no formally assigned community

leader. The Community of Linguistic Innovation has

been started by a group of linguistic enthusiasts. An

informal community leader takes the responsibility

for stimulating the members to interact. The

development of these public knowledge places offer

a unique opportunity for all educators to learn and

collaborate, despite their social and economic

background.

As said, the download phase has been conducted

with NodeXL, all likes and reactions on the Facebook

posts in the two cases were downloaded during three

periods described by Brown (2001) and Grossman et

al (2001). These periods were operated as a starting

point for the analysis of interaction patterns in the two

cases. We made some adjustments to ensure that the

phases better suit the short-term activities in these

communities. Nevertheless, the first period (4 weeks)

which was downloaded is defined as the introduction

phase. The central focus of this phase is the formation

of a group identity, in which teachers form a pseudo-

community with little interaction. The second phase

concerns the evolution stage (2 weeks). In this stage,

participants share thoughtful ideas. In the final stage,

after a relatively longer period of time and involving

intense association with others, one achieves

camaraderie (6 weeks).

In the convert phase, the social development

within these two cases was analysed using the

concepts central to the genre-theory described in the

work of Naaman et al (2010) to identify the

interaction patterns within two online WKCs in

Facebook, these interactions patterns were converted

by using NodeXL. In the convert stage, the messages

within the WKCs are coded with the genres described

by Naaman et al (2010). The genres introduced were

shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Genres.

Genre(s) Example(s)

Statements / Random

Thoughts

“It feels good to be

appreciated…”

Opinions “I would like to offer my

heartfelt congratulations

to…”

Information Sharing “For those of you who

missed <user>’s

Webinar…”

Introduction “Hello everyone. I am…”

Self-promotion “Please, read my blog

about…”

Me now “I’m watching the webinar

of…”

Question “Can anyone recommend

a nice, powerful, dynamic

and innovative tool for

presentations?”

Presence maintenance “Good morning all…”

Anecdotes (me) “My students mostly use

Moodle as a …”

Anecdotes (others) “<user> told me an

example of…”

When encoding the Facebook-nodes, we used

these genres as a base. For example, since Grossman,

et al (2001) suggested that online WKCs evolve with

a beginning phase where (new) members introduce

themselves, we have added a genre in which one

introduces them: ‘introduction’. Ultimately, the inter-

action patterns describe the development of WKCs

visualized through the various types of interactions

which occur.

Interaction Patterns in Web-based Knowledge Communities: Two-Mode Network Approach

101

In the visualization phase, we exported the

converted data from NodeXL into Gephi in order to

create relevant networks. These networks are visuali-

zed by following a two-mode network approach. A

two-mode network is also often called an affiliation,

bimodal or bipartite network. It means that the matrix

may not represent a network with the same entities

(Monge and Contractor, 2003). In the context of this

research, this is a network were authors are connected

to the genre of their interactions within Facebook. In

this case, the rows denote individuals, the columns

denote different types of posting (genres) and the

cells are filled with the type of interaction (like or

reaction). Broadly speaking, two basic approaches are

available to analyse two-mode data. Borgatti and

Halgin, (2011) distinguish the “conversion” approach

and the “direct” approach. In the conversion approach

visualizes one or both modes of the two-mode dataset

are converted into two one-mode projections which

are then analysed and separated. In the direct

approach, which has been carried out in this study,

both modes are analysed in a single graph.

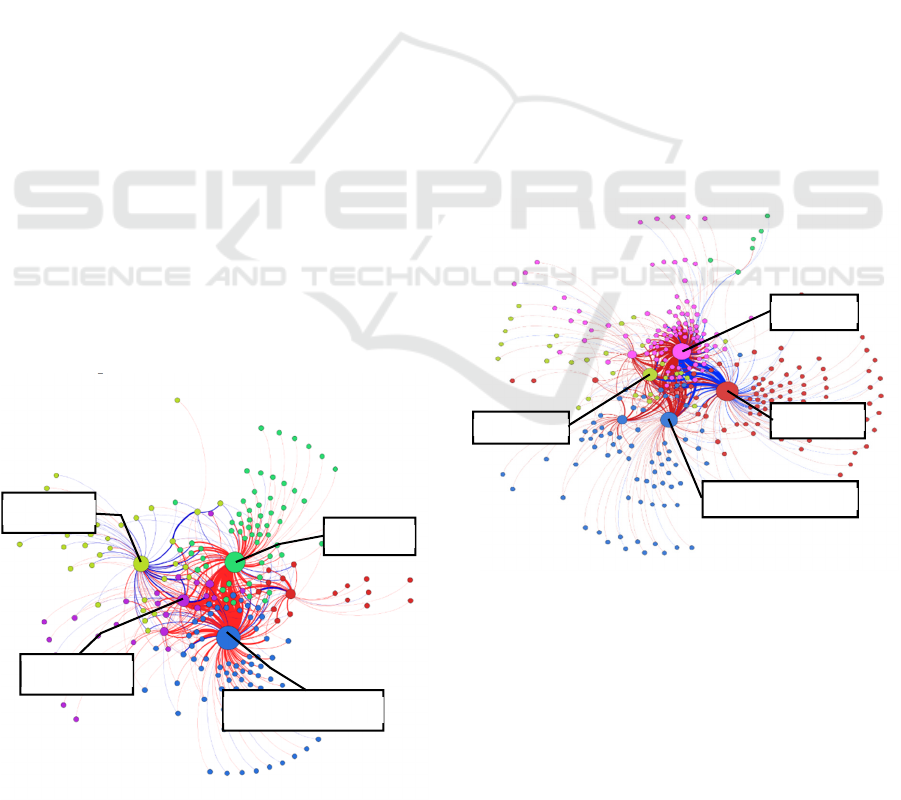

The colors

in the graphs represent characteristics assigned to the nodes

or edges, for example the genre or type of interaction. The

size of the nodes represents the frequency a certain genre

leads to an interaction.

Effectively identifying interaction patterns within

networked structures was done by modularity

analysis. Modularity is a measure that shows the

density of edges inside groups as compared to edges

between groups (Newman, 2006). Networks with a

high modularity have dense connections between the

nodes in a groups and sparse connections between the

nodes in different groups. Modularity is often used as

an optimization method for detecting community

structures in networks, but in this study we use

interaction patterns to define the dense groups of

members in a WKC. Besides the modularity, we also

use some descriptive measurements to describe the

developments within the two cases.

3 RESULTS

We conducted a systematic content analysis and

network analysis to define – in three different phases

(beginning, evolution and maturity) – the underlying

social interaction patterns in the two WKCs. The

interaction patterns are operationalized by using the

genres, described in the work of Naaman, Boase, and

Lai, (2010), see Table 1 on the previous page for the

genres and a realistic example from the Facebook-

data. In the following paragraphs, we describe the

resulting interaction patterns for each case in various

phases.

3.1 Case 1

The first online web-based knowledge community we

analysed in this research was the “Community of

Learning Innovation” case. Community of Learning

Innovation is a WKC that belongs to a Facebook

group page of a Massive Open Online Course

(MOOC). The goal of this MOOC is to teach

educational stakeholders more about course-design

by using educational technology in order to obtain

extensive practical experience with online technolo-

gies and to develop a working understanding of

incorporating successful online teaching strategies

into the practices of educators. The lessons took place

within Coursera, but the mutual knowledge exchange

(and collaborative development of knowledge)

largely took place on external social media platforms,

such as Twitter and Facebook. The MOOC officially

started in the last week of July 2014, but the

interactions and introductions of the participants

started two weeks earlier. The duration of the MOOC

officially was eight weeks, but including the four

weeks before the starting date, we analysed this case

over twelve weeks.

The first four weeks form the beginning or sowing

phase; during these four weeks, some participants

introduced themselves and shared knowledge. The

following two weeks forms the evolution phase;

during these weeks, the network of participants grew.

The last six weeks forms the maturity or harvesting

stage; during this stage, the online web-based know-

ledge community professionalizes. This is the result

of the course content of the MOOC and the increasing

depth of conversations. However, during the three

phases the number of co-likes decreased, while the

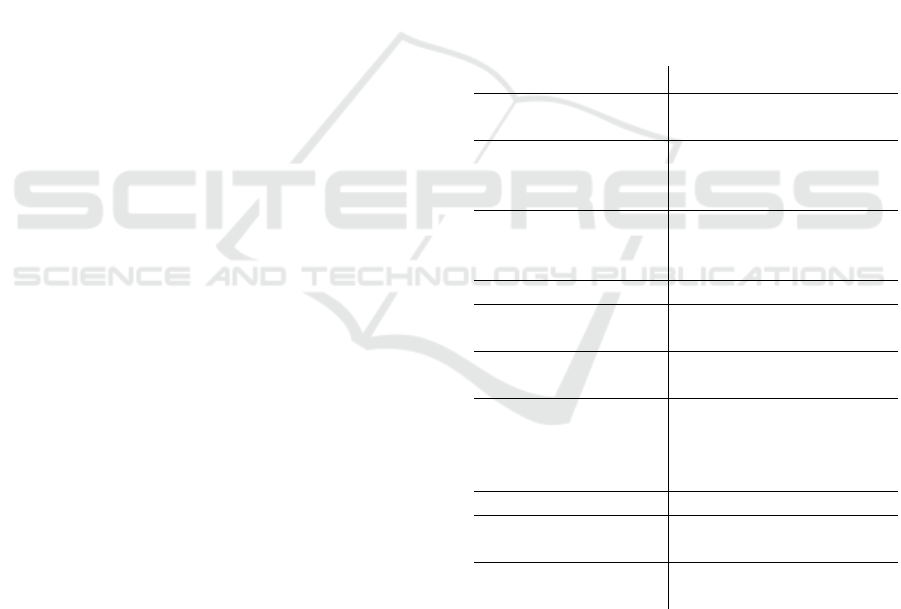

number of co-comments increased (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Level of Interactions (Case 1).

80%

76%

75%

20%

24%

25%

0

20

40

60

80

100

Beginning Evolution Maturity

Co-Likes

Co-

Comments

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

102

3.1.1 Beginning Phase in Case 1

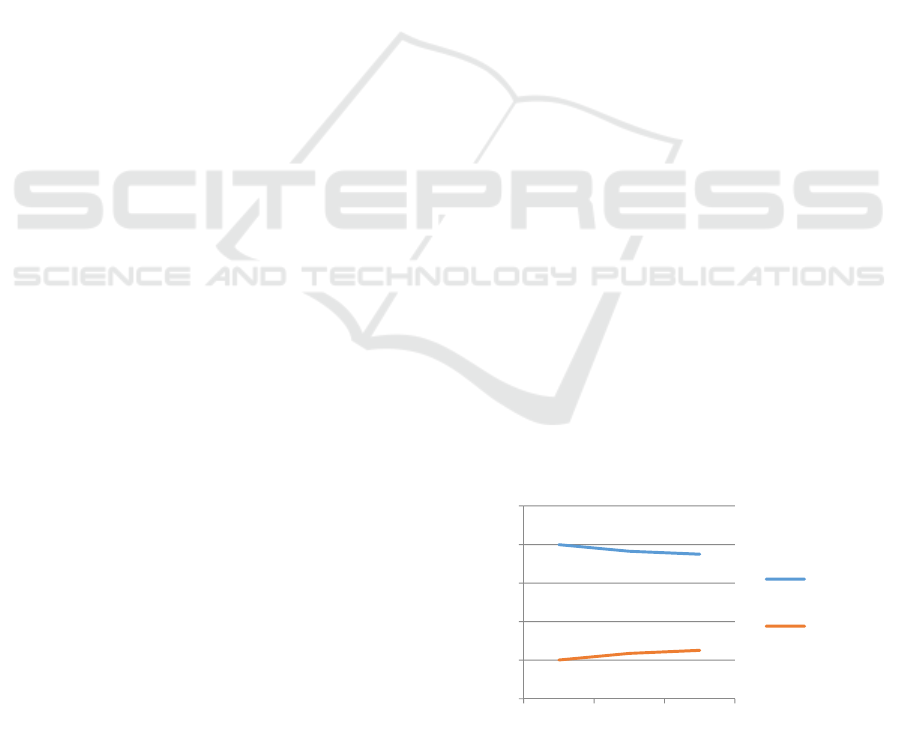

Figure 2: Beginning phase Case 1.

The main objective of the first community is to bring

teachers together who want to improve their online

teaching competencies. The following introdu-ctory

text, derived from the course description, gives a brief

explanation of the learning development the

educators need to go through: “The overarching

learning objective is to help existing educators to

establish or improve their own online or blended

teaching practices. As part of the course, there was

the opportunity to develop an own understanding of

effective online teaching practices and their

relationship to the use of different technologies. The

participants have also been encouraged to

progressively design and reflect upon the own online

learning activity, assessment or resource for use in the

own class”. The learning objectives described by the

instructors show to what extent and in what areas the

teachers develop themselves. They learn to establish

and improve their own online or blended teaching

practices; they learn to develop an understanding of

effective online teaching practices, and their

relationship to the use of different technologies. The

Facebook community created for this MOOC started

for socialization purposes. However, despite the lack

of a specific goal, many people still actively

participated in the community. A remarkable fact in

the analysis is that the vast majority of interactions

within the community consisted of participants

‘liking’ information, comments or questions instead

of responding to the content. The sociogram (Figure

2) show the network within Facebook, in which the

interactions were based on co-comments and co-likes

(initiator and responder). The results show an amount

of 349 nodes and 573 edges. The genres of these

interactions are related to questioning and individual

introductions. The modularity within the community

is 0.517 (51,7%), where a high modularity means

more edges (interactions between actors) within the

module than you expect by chance. Based on the

analysis of the modularity, we can identify 14

modules of interaction. The majority of these

interactions are co-likes (red edges), where members

appreciate the contributions of others. The blue edges

represent individual comments on certain genres.

3.1.2 Evolution Phase in Case 1

During the beginning phase, new members introduce

themselves to the community. In the evolution phase,

we see 283 nodes and 474 edges and a modularity of

0.335 (33.5%) with 5 clusters. The genres in this

phase shift from mainly introducing one to sharing

information and opinions. In total, the modularity is

0,335 (33,5%) and this resulted in a network of five

clusters. The major cluster is the exchange of infor-

mation, the second cluster represents the participants

who share their opinions; the third cluster describes

the number of questions from the participants; and the

fourth cluster consists of introducing oneself, and

therefore this fourth cluster strongly connects to the

genre ‘self-promotion’. In the final cluster in our

study, participants gave anecdotes about themselves,

to describe their best practices. In deeply conversa-

tions (information sharing and giving opinions.

Figure 3: Evolution Phase Case 1.

Question

Information sharing Introduction

Question

Information sharing

Opinions

Introduction

Interaction Patterns in Web-based Knowledge Communities: Two-Mode Network Approach

103

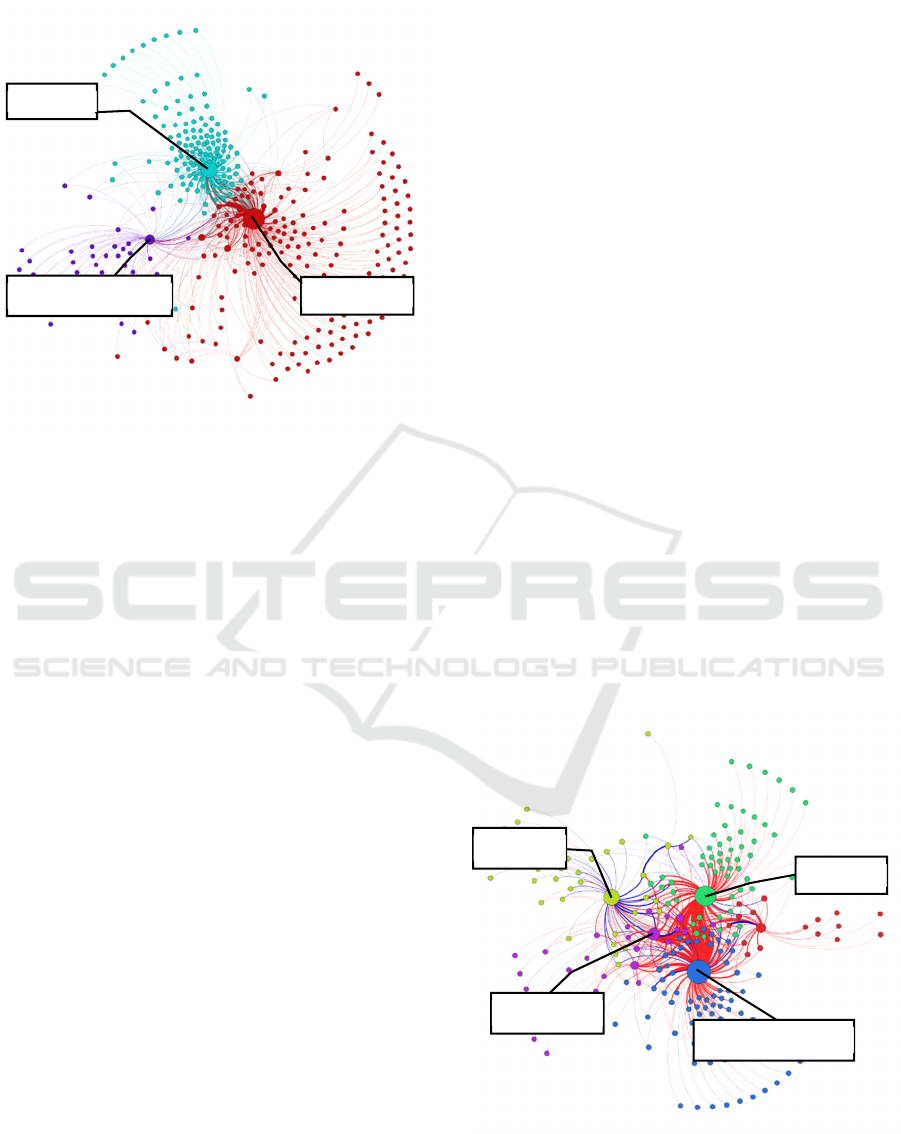

3.1.3 Maturity Phase in Case 1

In the maturity phase, we see 446 nodes and 845

edges. The modularity in this phase is 0.276 (27,6%),

with 6 clusters. The largest cluster or genre of the

activities within the web-based knowledge communi-

ty remains stable compared to the evolution phase:

individuals within the community ask questions,

share knowledge and information, and thank the

teachers and other participants for their feedback and

organization. Participants increasingly ask for help

from their colleague-students instead of teachers,

which underlines the benefits of a web-based know-

ledge community. The majority of interactions within

the community are ‘likes’ (~ 75 per cent) and the

remaining are comments, that are responses to

questions.

Figure 4: Maturity Phase Case 1.

3.2 Case 2

The Community of Linguistic Innovation is the

second Facebook group we have analysed in this

research. This group started in mid-September 2013.

The intentions of the Facebook group were to

researchers of English language who teach applied

linguistics. The community aimed to provide a

platform for English language professionals from

around the world to share and exchange teaching and

research information and ideas, despite their

background. The ultimate goal is not only to improve

the knowledge and skills on a micro-level (indivi-

duals), but essentially the improvement of skills and

competences on a macro-level (teaching society). The

content within the community is diverse, from topics

such as the development of curricula and materials to

language teaching methodology and classroom mana-

gement. Figure 5 shows that the mode of interaction

Figure 5: Level of Interactivity within Case 2.

over time increasingly shifts from the relatively

passive ‘liking’ of content, to the more actively

‘commenting’ on content.

3.2.1 Beginning Phase in Case 2

The ‘beginning’ phase of the Community of

Linguistic Innovation consisted in its first phase of

894 nodes and 1.574 edges in four weeks. The

network mainly consisted of females (64,43%). At the

start, the community leader introduced the formal

goals for the community and made the participants

aware of these goals. The community aims to provide

a platform for English language teachers from around

the world to communicate, share knowledge and

collaborate in order to improve their own working

practices, skills, effectiveness and/or competency.

The results of the content analysis and social network

analysis within Community of Linguistic Innovation

clearly show that from its first moments, the

introduction of the community has a special role, with

Figure 6: Beginning Phase Case 2.

90%

87%

84%

10%

13%

16%

0

20

40

60

80

100

Beginning Evolution Maturity

Co-Likes

Co-

Comments

Question

O

p

inion

Me now

Information sharin

g

Information sharin

g

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

104

185 interactions. However, within a few days, this

picture completely changed. When the guidelines

were clear and the participants introduced them-

selves, the participants considered it time to share

their knowledge, to ask questions and share opinions,

this is clearly visualized in Figure 6. The information

sharing genre is a cluster that supplants the other

clusters. The majority of the members (90,22 percent)

within the community liked the exchange of

knowledge with their colleagues. Almost 10 percent

(9,78%) of the members commented on the posts,

these are often questions, comments, articles or

announcements.

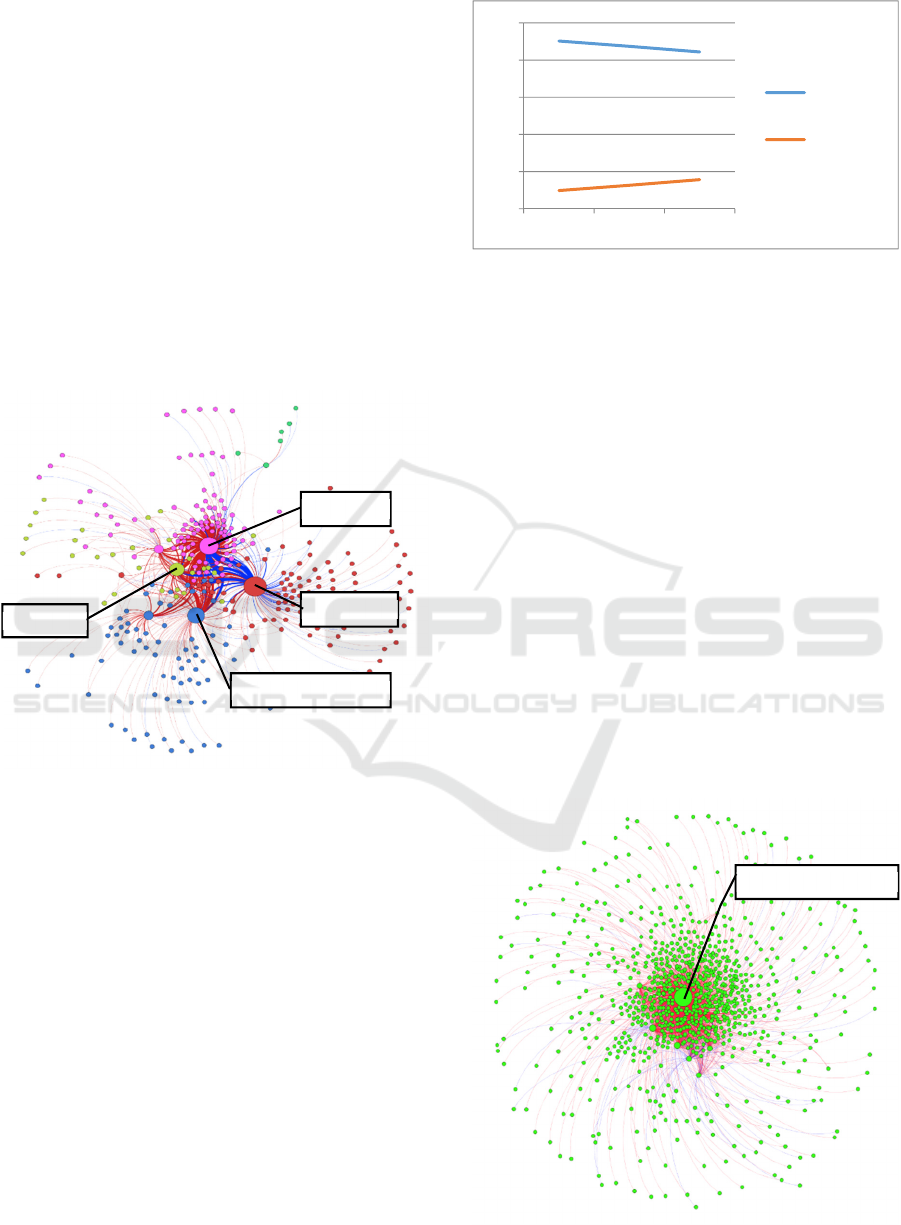

3.2.2 Evolution Phase in Case 2

The ‘evolution’ phase of Case 2 consisted of 283

nodes and 474 edges in a period of two weeks. The

interaction during these weeks has led to a modularity

of 0.335 (33.5%). The majority of the members in the

community shared, liked and otherwise reacted to

knowledge within the online place. This is – when

following the number of comments and ‘likes’ – the

most appreciated form of interaction by the members.

Another form of interaction; sharing opinions, and

exchanging opinions strongly relates to information

sharing. The code for the exchange of information

with a ‘personal touch’ was ‘opinion’, because of that

the information exchange is not completely objective.

During the evolution phase an increase in co-

comments can be identified, there was an increase

from 9.78% to 12.58%, which show an increase

of2.80% in comparison to the beginning phase. This

may indicate a growing sense of connectedness. The

other 87.42 percent of the interactions are co-likes.

Figure 7: Evolution Phase Case 1.

3.2.3 Maturity Phase in Case 2

The ‘maturity’ phase of the Community of Linguistic

Innovation consisted of 446 nodes and 845 edges

after a period of analysis of five weeks. This resulted

in six clusters with a modularity of 0.276 (27.6%).

The majority of interactions in the maturity phase of

the Community of Linguistic Innovation is

represented in co-likes (84.38 percent), and we

visualized this by the red edges in Figure 8. The major

part of the participants decided to easily ‘like’

another’s message. The remaining 15.62% are

‘comments’ on initial posts (blue edges). Again, we

see an increase in the volume of comments rather than

‘likes’. The interactions within the web-based

knowledge community were mostly based on

information sharing, expressing opinions and

introducing new members. Since Community of

Linguistic Innovation intended to be a continuous

developing community, the introduction of new

members is a continuous process. As the sharing of

information and expressing of opinions increases, we

can confirm that the individual’s self-confidence to

actively participate in the online environment is

rapidly increasing after a certain period of time,

whether this might be by liking other’s reactions or

posts or by commenting on others.

Figure 8: Maturity Phase Case 1.

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, multiple interaction patterns were

identified that represent the development of web-

based knowledge communities. These interaction

patterns were identified during three phases: the

Question

Information sharing

Opinions

Introduction

Question

Opinion

Me now

Information

Interaction Patterns in Web-based Knowledge Communities: Two-Mode Network Approach

105

introduction, the evolution and the maturity of the

community. The resulting patterns provide insight

into how WKCs evolve over time and provide insight

into the increasing voluntary use of such WKCs. The

patterns were identified by evaluating two WKCs in

which innovative educational stakeholders interact

with likeminded others with the common purpose to

improve education. In this study we studied the

development of these WKCs. A typical method for

analysing and visualizing the development of such

cases is by means of conventional methods available

in statistical computer programs (for example SPSS

and Amos). However, in this study we have opted for

a method based on secondary data: social network

analysis. We analysed and visualized the

development of WKCs by using a two-mode network

approach where the connectivity is represented in a

relationship between individuals and the genre of

conversations. The size of the nodes represent the

weight of the nodes. The larger nodes embody the

genre of interactions. The larger the nodes, the more

relevant the genre. The colour of the relations

characterize the type of interaction which can be a

more passive ‘like’ or a more active ‘comment’. The

majority of likes were given when one introduces

themselves, in case of opinions the number of

comments increased.

The research question posed in the beginning of

our study was: What kind of interaction patterns

describe the development of an online web-based

knowledge community in an educational context? To

answer this research question, we have used the

genre-theory introduced by Naaman et al (2010). Due

to the differences in the two WKCs, we identified

different interaction patterns. In the first case –

Community of Learning Innovation – the participants

all have a common interest: improving their online

teaching competencies. In a MOOC, the participants

have already learned the necessary skills to deliver

online teaching, but in the WKC-environment

discussions about the topic continued. In the second

case – Community of Linguistic Innovation –

individuals took part in an independent WKC with the

central topic of ‘improving English teaching’. In this

WKC, the participants discussed the topic from

various perspectives and at different levels of

knowledge. Despite the large differences between the

two WKCs, there are also some similarities. In both

WKCs, we identified a remarkably similar

development of phases. In the first phase, individuals

introduced themselves. In the second phase, the

individuals were more confident in sharing external

information and in the third phase, individuals felt

confident enough to share their opinions. In this

phase, a form of friendship could be identified that

was only minor in nature, but nonetheless, it is

indicative of the success. The members dared to

express their opinions openly– be it online and

anonymously in the – communities. Since the size of

the Community of Linguistic Innovation is

continuously increasing, each new participant

introduced themselves in contrast to the Community

of Learning Innovation were the majority of members

registered at the same time when the MOOC started.

Especially the first members introduced themselves,

but this trend gradually decreased.

To conclude, this research improves our

knowledge about WKCs in general and gives insight

into the sociological development of WKCs

described with the genres labelled in the two-mode

social graphs. The success of a WKC depends on the

individual willingness to create a sense of group

feeling (or community feeling). Each individual must

feel confident to add relevance to the community

before the individual and other members can benefit

from it. One of the activities which stimulates the

individuals willingness to share information is by first

letting them introduce themselves to the other

members. After a relatively short time frame, the

members share the more formal information and after

a couple of weeks they also share their opinions about

the information others give and share more

opinionated information/knowledge. Awareness of

these stages and the related patterns increases the

chance to successfully develop web-based knowledge

communities.

One of the limitations in this study is the genre

determination, since some interactions fit multiple

genres. If for example someone asks “Do you also

think that English should be the global language?”,

this statement can be judged as a question, but also as

an opinion. In such cases, we have labelled it as a

question. Since we have chosen to connect one genre

per interaction. In upcoming studies we recommend

to use multiple genres per interaction.

REFERENCES

Borgatti, Stephen P, and Halgin, D. S. (2011). Analyzing

affiliation networks. In The Sage handbook of social

network analysis, pp. 417–433.

Brown, R. E. (2001). The process of community-building

in distance learning classes. Journal of Asynchronous

Learning Networks, 5(2), pp. 18–35.

Chugh, R. (2015). Do Australian Universities Encourage

Tacit Knowledge Transfer? In Proceedings of the 7th

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

106

International Joint Conference on Knowledge

Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge

Management, 3(April), pp. 128–135. http://doi.org/

10.5220/0005585901280135

Grossman, P., Wineburg, S., and Woolworth, S. (2001).

Toward a theory of teacher community. The Teachers

College Record, 103(6), pp. 942–1012.

Lin, H., Fan, W., Wallace, L., and Zhang, Z. (2007). An

empirical study of web-based knowledge community

success. In System Sciences, 2007. HICSS 2007. 40th

Annual Hawaii International Conference.

Monge, P., and Contractor, N. (2003). Theories of

Communication Networks. New York: Oxford Press.

Naaman, M., Boase, J., and Lai, C. (2010). Is it really about

me?: message content in social awareness streams. In

2010 ACM conference on Computer supported

cooperative work.

Newman, M. E. J. (2006). Modularity and community

structure in networks. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, 103(23), pp. 8577–8582.

Sheng, J. and Yao, J. (2004). Teacher’s Professional

Development in Psychological Perspective. Journal of

Beijing Normal University (Social Science Edition), 1,

005.

Tseng, F. C., and Kuo, F. Y. (2014). A study of social

participation and knowledge sharing in the teachers’

online professional community of practice. Computers

and Education, 72, pp, 37–47.

Vollenbroek, W., Jagersberg, K, Vries, S, and

Constantinides, E. (2014). Learning Education: An

“Educational Big Data”approach for monitoring,

steering and assessment of the process of continuous

improvement of education. In European Conference in

the Applications of Enabling Technologies.

Windahl, S. and Rosengren, K. E. (1978). Newsmen’s

professionalization: Some methodological problems.

Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 55(3),

pp. 466.

Interaction Patterns in Web-based Knowledge Communities: Two-Mode Network Approach

107