Network Overlap and Network Blurring in Online Social Networks

Nan (Andy) Zhang

1

and Chong (Alex) Wang

2

1

Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, University of Jyvaskyla, Agora, 40100, Jyvaskyla, Finland

2

Department of Information Systems, City University of Hong Kong, 83 Tat Chee Avenue, Hong Kong, China

Keywords: Social Networking Site, Online Community, Affective Commitment, Network Overlap, Network Blurring.

Abstract: Online communities and the online social networks embedded become a prominent medium for social

interactions. The success of social media depends on users’ willingness to continue investing their time and

efforts in the absence of economic rewards, making psychological attachment critical to online communities.

While prior studies identify that members do develop psychological commitment to online communities, why

and how the commitment arises remain underexplored. This study focuses on the relationship between

network overlap, a common feature of online social networks, and affective commitment to an online

community. Drawing on the commitment theory and social network boundary theory, we argue that the effect

of online/offline network overlap is partially mediated by network boundary blurring. Meanwhile, contrary

to industrial wisdom, the direct impact of network overlap on commitment is negative. Our empirical study

supports our proposal. It indicates that it is critical to help users integrate online and offline social networks.

Without success social network boundary blurring, high level of network overlap may backfire.

1 INTRODUCTION

As one of the most important social media

applications, social networking site (SNS) has

revolutionized how media contents are created and

consumed and has been among the most mentioned

buzzword in the business in recent years. However,

as the initial flame cooling down, business critiques

began to question about the sustainability of SNSs in

the absence of formal ways to award users for

continuous participations. Some even argue that

online social networking and online communities

may only be something that matter hugely until, very

suddenly, they don’t matter at all (Hirschorn, 2007).

A recent report indicates that Facebook is losing teen

audience (Tech Times, 2015) and we see many once

hot SNSs falling. For SNSs to survive and match the

hype, one of the major challenges is to maintain

active users’ participations. Without the right

mechanism to sustain online activities, SNSs will

inevitably become something “hot today and gone

tomorrow” (Knowledge@Wharton, 2006).

Supported by social networking functions, users

form online communities in SNSs. Through online

social networking activities such as sharing personal

experiences and opinions, playing online games, and

providing and receiving social supports, SNSs users

generate psychological attachment (affective

commitment) to their online communities. Researchers

identify that this affective commitment can influence

SNSs users’ post-adoptive usage and contribution

behaviors. For example, drawing on commitment

theory, Bateman et al. (2011) explain how commitment

to an online community influences the likelihood that

a member will engage in particular behaviors.

Similarly, Tsai and Bagozzi (2014) identify a

relationship between anticipated emotions and

behavioral desires in an online community. However,

it is still not clear how the affective commitment is

developed in online communities.

Meanwhile, recognizing the bonding power of

offline, strong-tie social connections, practitioners

make significant efforts to bring current users’ offline

friends to the online community, hoping that it will

make online social networking experiences more

engaging. This strategy significantly increases the

overlap between online and offline social networks.

Despite the prominence of overlap between online

and offline networks, few study tried to explore the

relationship between network overlap and user’s

commitment to online communities (Zhang and

Venkatesh, 2013).

To fill these gaps in our understanding and shed

lights on the effectiveness of bringing in offline social

Zhang, N. and Wang, C.

Network Overlap and Network Blurring in Online Social Networks.

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2016) - Volume 2, pages 327-332

ISBN: 978-989-758-187-8

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

327

connections, we study the relationship between

network overlap and user commitment to online

communities in the context of SNS. Based on

commitment theory and network boundary theory, we

argue that the overlap between online and offline

social networks have both a direct and a mediated

effect on affective commitment. While the mediated

effect, through network blurring, is positive, the

direct effect of network overlap is negative, contrary

to the popular belief. Without successfully blurring

the boundary between the two networks, bluntly

increasing network overlap may result in confusion

and a utility focus in the usage of online SNS tools,

which impedes the development of affective

commitment and hurt continuous participations on

SNSs. Our empirical study supports this theoretical

proposal and confirms a partially mediated effect of

network overlap on affective commitment to an

online community.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

Existing research has significantly enhanced our

understanding about users’ behaviors in SNSs. For

example, the effects of moral beliefs (Xu et al., 2015),

homophily between online peers (Gu et al., 2010) and

reputation (Tang et al., 2014) have been identified.

However, we would like to argue that the existing

models failed to capture an important aspect of online

communities, that is, the social network embedded in

an online community is formed by peers from both

offline and online worlds. Such a network overlap can

influence the focal people’s behaviors (Zhang and

Venkatesh, 2013). Thus, drawing on commitment

theory and boundary theory, we will go a step further

to focus on the relationship between network overlap

and user commitment to online communities.

2.1 Affective Commitment

Commitment is individuals’ enduring desire to stay in

a community or an organization. It is agreed that

individuals’ commitment to a community can affect

their intention to be a part of the community (Wasko

and Faraj, 2005).

Commitment theory was used to explain why

volunteers at non-profit organizations varied in their

level of dedication (Becker, 1960). In SNSs, user’s

usage of the services is primarily voluntary rather

than mandatory, and switching from one website to

another similar site is relatively easy and involves low

costs (Brynjolfsson and Smith, 2000). Thus,

commitment theory is an appropriate framework for

investigating users’ voluntary behaviors in SNSs

(Bateman et al., 2011). In the context of SNS, the type

of commitment that a member may have to an online

community is affective.

Affective commitment is defined as “the degree to

which people experience an emotional attachment

with their organization” (Meyer and Allen 1991, p.

67). Members who have developed a strong affective

commitment to an community generally like that

community and identify with it, are more likely to

desire to be a part of conversations that occur in that

community, and therefore inclined to stay in

(Bateman et al., 2011). Despite the importance of

affective commitment, its antecedents in the context

of SNS are not clear. Therefore, we will identify the

factors that can influence the development of the

affective commitment in SNSs.

2.2 Social Network Boundary

Boundaries occur at points of discontinuity in space,

time, or function. Such a discontinuity is a boundary if

there is control or regulation of transactions across it

(Miller et al., 1978). From the social psychology

perspective, social network boundaries reflect an

individual’s perception of the differences between

different social environments (Morrison et al., 1985).

In the offline world, people employ a variety of

mechanisms to regulate their social networks

boundaries. Verbal and non-verbal communications,

territoriality behaviors and personal space creations

are identified as boundary-control mechanisms

(Altman, 1975). People can use body language to

block themselves from unwanted contacts. They can

also build up physical barriers to mark, defend and

limit others’ access to a network. Further, by altering

the distance and angle of orientation from others, the

individual creates an intimate zone reserved to avoid

intrusions from strangers. In general, different social

networks are separated from each other in the offline

world.

When social interactions are moved to SNSs, the

situation is changing. Some boundary regulation

mechanisms are not as efficient as it used to be in

offline world. Social network boundaries in the

context of SNSs are blurring. Online network

boundaries are obscure due to the absence of temporal

and spatial discontinuity helps to achieve absolute

separation (Pierce et al., 2001). Intimacy and reserve

are hardly secured as online discussions and

comments are mostly publicly observable. The

maintaining of network boundaries is more

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

328

challenging due to the rapid diffusion of information

among online peers. Such a blurring of network

boundary will influence the development of the

affective commitment to an online community.

3 THEORY DEVELOPMENT

Bateman et al. (2011) identify a positive relationship

between affective commitment and users’ intention to

stay in an online community. However, it is not clear

in the literature how online social networks help to

produce the affective commitment. Drawing on the

network boundary perspective, we propose that the

overlap between online and offline social networks

have both a direct and a mediated effect on affective

commitment. While the mediated effect, through

network blurring, is positive, the direct effect of

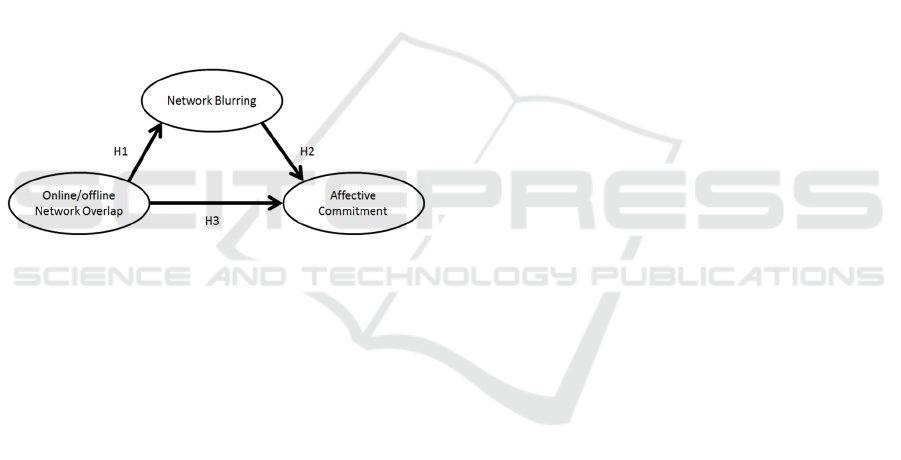

network overlap is actually negative. Figure 1 shows

our conceptual model.

Figure 1: Conceptual model.

3.1 Online/Offline Network Overlap

Online/offline network overlap is defined as extent to

which a focal SNS user’s peers in his/her online social

network are also peers in his/her offline social

network. It is an objective description of the

composition of the focal user’s online network.

Online communities are extensions of people’s

offline social relationships. On the one hand, people

develop new friendship online. On the other hand,

they tend to communicate offline acquaintances on

the websites as well. Meanwhile, SNSs vendors also

use the strategy to facilitate a quick diffusion of their

services by encouraging users to send invitation

emails to their offline peers to let them join the SNS.

As a result, part of the peers in the focal users’ online

community is also friends in their offline networks.

Thus, an overlap between the focal user’s online and

offline social networks is generated.

3.2 Network Blurring

While online/offline network overlap reflects the

composition of a focal SNS user’s online social

networks, we introduce another construct, network

blurring, to describe the user’s perception of the

similarities between online and offline social

networks. Specifically, network blurring is defined as

extent to which a focal SNS user believe that his/her

online and offline social networks are the same or

inseparable.

3.3 Affective Commitment, Network

Overlap and Network Blurring

Since most behavior is closely embedded in networks

of social relations, the structure of an individual’s

social network will influence the individual’s

behavior (Reagans and McEvily, 2003). In the current

context, network overlap, as a reflection of the pattern

of an individual’s online social network, will impact

his/her affective commitment to an online

community. The influences are two folds. Depending

on the focal user’s perception of the similarities

between the two networks, the impact could be either

positive or negative. Specifically, network overlap

could have both a mediated and a direct effect on

affective commitment. While the mediated effect,

through network blurring, is positive, the direct effect

is negative

Network overlap could have positive effects on

SNSs users’ affective commitment because of two

reasons. First, the focus of trust belief can shift from

those offline peers to the online community (Meyer et

al. 1998). People trust their offline peers more than

their pure online peers in general due to the better

ability of face-to-face communications in terms of

trust-building cues transmission (Kumar and

Benbasat, 2006). When the network overlap is high,

due to the existence of trustful offline peers, the

online community becomes a more trustful space for

the focal user. In such an environment, it is easier for

the focal user to develop affective commitment to the

online community.

Second, the focus of commitment can shift from

those offline peers to the online community (Meyer et

al., 1998). In the current context, when the network

overlap is high, traditional boundaries between online

and offline network is blurring. The two networks can

be integrated together. Therefore, people may shift

the focus of the affective commitment from their

offline communities to the online communities. When

the overlap is increasing, the proportion of offline

Network Overlap and Network Blurring in Online Social Networks

329

peers is increasing, and consequently, the possibility

of the commitment focus shifting is larger.

The focus of trust belief and affective

commitment can shift from offline peers and

communities to an online community. However, the

transference would be hard if the focal user thinks that

the two communities are different or separable. The

user may use some methods to maintain the boundary

(e.g. group peers into different categories). Due to the

approach, the transference of trust belief and affective

commitment will be blocked. Thus, the positive effect

from online/offline network overlap on affective

commitment is mediated by network blurring.

The degree of network overlap can increase the

degree of network blurring. Conversations in SNSs

are not limited by temporal and spatial separations.

SNSs therefore free individuals from the

geographical boundaries. When peers start to

communicate to each other in both online and offline

environment, the natural boundary of online and

offline network is blurring. The focal individual’s

perception of the similarity between these two

networks is therefore increasing.

H1: The degree of online/offline network overlap

increases the focal user’s network blurring.

It would be easier for members to shift the focus

of their trust belief and affective commitment from

one to another if they do not view the two

organizations as fundamentally different (Thompson,

2001). With the same logic, if the degree of network

blurring is high, he/she may shift the focus of trust

belief and affective commitment from offline peers

and communities to online communities as well. In

this case, it is easier for the user to either shift the

existed affective commitment to the online

community or develop new one to the online

community.

H2: The degree of network blurring increases the

focal user’s affective commitment to the online

community.

When the positive impact of network overlap on

affective commitment is mediated by network

blurring, the direct effect is negative. When most of

peers in an online network come from the focal user’s

offline network, the online community becomes a

complementary communication tool of the offline

network. Although, people may communicate with

each other predominantly online, their relationships

are still based on the offline contexts (e.g. classmates,

relatives and colleges). In this case, high degree of

network overlap could result in a feeling of triviality

of the online community. Online community becomes

a communication platform or maintaining tool for

different relationships embedded in the offline

network. Thus, the high degree of overlap may inhibit

the focal user from forming affective commitment to

the online community.

H3: Online/offline network overlap decreases the

focal user’s affective commitment to the online

community.

4 METHODS AND PROCEDURE

Items for affective commitment are adopted from

Allen and Meyer (1996) with modifications for the

SNSs context where needed. Online/offline network

overlap is measured by the questions like “I knew

most of my friends in my virtual community before I

joined this website.” Network blurring is measured by

the questions like “It is often difficult to tell the

difference between my online social network and my

offline social network.”

An online survey is carried out among the students

from a Hong Kong based university. We select

students enrolled in a course in the business school.

The online survey lasts for two weeks and two

reminders for participation are sent out during the

period. 165 out of 344 students complete the survey.

The response rate is 48%.

5 DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULT

5.1 Measurement Model Assessment

We use covariance-based structural equation

modeling in AMOS to test our measurement model.

The fit statistics for the measurement model

(χ

2

=60.15, df=32, χ

2

/df=1.88, RMR=0.10, GFI=0.93,

NFI=0.93, CFI=0.96, RMSEA=0.07) indicate good

fit. Further, the scales exhibit good reliability

(composite reliabilities range from .746 to .906),

good convergent validity (all item loadings are above

0.7 and the AVE is greater than 0.5 for all constructs),

and good discriminant validity.

5.2 Results of Hypotheses Testing

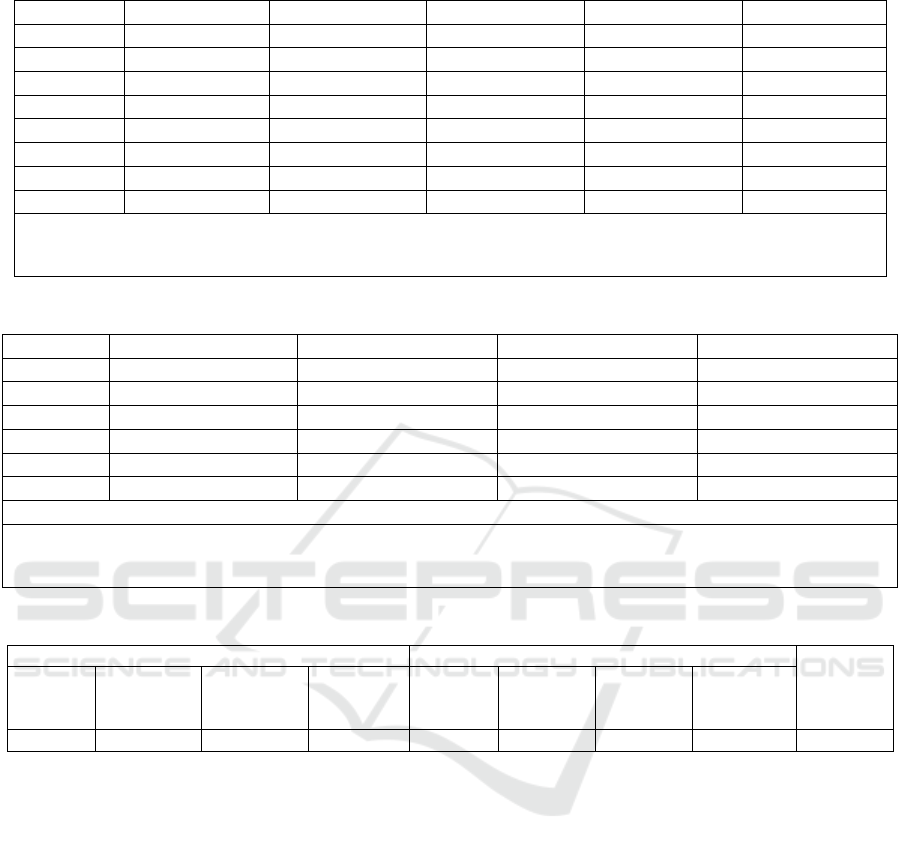

First, we follow Baron and Kenny’s (1986) causal

step approach to test our hypotheses in regressions.

The results suggest that the effects from

online/offline network overlap on affective

commitment are partially mediated by network

blurring (see Table 1).

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

330

Table 1: Regression results.

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5

IVs Controls NO→AC NO→NB NB→AC Full Model

Age .100 .097 .206

**

.031 .019

Gender -.109 -.101 -.031 -.104 -.089

SNS Exp. .066 .049 .080 .051 .019

SN .175

*

.180

*

.071 .146

#

.154

*

NO -.083

.180

*

-.151

*

NB

.349

***

.376

***

R

2

.056 .063 .082 .172 .193

Notes: AC=Affective Commitment; NO=Online/offline Network Overlap; NB=Network Blurring; SNS Exp.=Social

Networking Site Experiences; SN=Subjective Norm.

#

p< 0.1,

*

p < 0.05,

***

p < 0.001

Table 2: Bootstrapped CI Tests for Direct Effects on Affective Commitment.

IVs Effects 2.5% lower bound 97.5% upper bound Zero included?

Age .031 -.206 .267 Yes

Gender -.229 -.656 .147 Yes

SNS Exp. .013 -.087 .113 Yes

SN .156

*

.006 .305 No

NO -.153

*

-.304 -.003 No

NB .366

***

.222 .510 No

R

2

=.193

Notes: AC=Affective Commitment; NO=Online/offline Network Overlap; NB=Network Blurring; SNS Exp.= Social

Networking Site Experiences; SN=Subjective Norm.

#

p< 0.1,

*

p < 0.05,

***

p < 0.001

Table 3: Bootstrapped CI tests for mediation effects on affective commitment.

Mediation Test (indirect effect) Full/Partial Mediation Test (direct effect)

Type of

mediation

Effect

2.5% lower

bound

97.5%

upper

bound

Zero

included?

Effect

2.5%

lower

bound

97.5%

upper

bound

Zero

included?

.069 .005 .160 No -.153 -.304 -.003 No Partial

Second, to further verify the partially mediated

effect, we use PROCESS to conduct bootstrapping

tests in SPSS with 10000 resamples. Table 2 and

Table 3 report the 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Partially mediated effect is therefore verified.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Affective commitment formation is critical to online

communities, which could enhance user engagement

and produce continuous participations. Bring offline

social connections online seems to be an intuitive

remedy that enable the community to leverage on

close ties for commitment development. Yet, our

study suggests that this strategy, while broadly used,

may not always bring positive results. It depends on

whether the online interactions were able to create a

sense of boundary blurring. Successful boundary

blurring triggers affective commitment spillover from

offline connections to the online community.

However, if the overlap fails to achieve boundary

blurring, the next effect would be negative. Users

would mostly treat online community as a

supplementary channel to connect, while impede the

development of affective commitment.

This study contributes to research on user

behavior in SNSs. Our study suggests that the

network boundary lens is pertinent to understand the

development of users’ psychological bond with the

online community. We identify that network blurring

mediates the effect from network overlap on

commitment. Controlling for the mediated effect, the

direct effect of network overlap is negative.

Network Overlap and Network Blurring in Online Social Networks

331

REFERENCES

Allen, N. J., and Meyer, J. P. 1996. Affective, continuance,

and normative commitment to the organization: An

examination of construct validity. Journal of

Vocational Behavior (49:3), pp. 252-276.

Altman, I. 1975. The environment and social behavior:

Privacy, personal space, territory, and crowding. Cole

Publishing, CA: Monterey.

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. 1988. On the evaluation of

structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science (16:1), pp. 74-94.

Bateman, P. J., Gray, P. H., and Butler, B. S. 2011. The

impact of community commitment on participation in

online communities. Information Systems Research

(22:4), pp. 841-854.

Becker, H. S. 1960. Notes on the concept of commitment.

American Journal of Sociology (66:1), pp. 32-40.

Brynjolfsson, E., and Smith, M. D. 2000. Frictionless

commerce? A comparison of internet and conventional

retailers. Management Science (46:4), pp. 563-585.

Gu, B., Konana, P., Raghunathan, R., and Chen, H. M. 2014.

The allure of homophily in social media: Evidence from

investor responses on virtual communities. Information

Systems Research (25:3), pp. 604-617.

Hirschorn, M. 2007. Web 2.0 bubbles. from http://

www.theatlantic.com, retrieved on January 12, 2016.

Knowledge@Wharton. 2006. Myspace, Facebook and

other Social Networking Sites: Hot today, gone

tomorrow? from http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu,

retrieved on January 12, 2016.

Kumar, N., and Benbasat, I. 2006. The influence of

recommendations and consumer reviews on evaluations

of websites. Information Systems Research (17:4), pp.

425-439.

Meyer, J. P., and Allen., N. J. 1991. A three-component

conceptualization of organizational commitment.

Human Resource Management Review (1:1), pp. 61-89.

Meyer, J. P., Irving, G. P., and Allen, N. J. 1998.

Examination of the combined effects of work values

and early work experiences on organizational

commitment. Journal of Organizational Behavior (19),

pp. 29-52.

Miller, J. G. 1978. Living systems. New York: McGraw-

Hill.

Morrison, T. L. 1985. Personal and professional boundary

attitudes and effective group leadership in classrooms.

The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and

Applied (119:2), pp. 101-111.

Pierce, J. L., Kostova, T., and Dirks, K. T., 2001. Toward a

theory of psychological ownership in organizations.

Academy of Management Review (26:4), pp. 298-310.

Reagans, R., and McEvily, B. 2003. Network structure and

knowledge transfer: the effects of cohesion and range.

Administrative Science Quarterly (48:2), pp. 240-267.

Tang, Q., Gu, B., and Whinston, A. B. 2012. Content

contribution for revenue sharing and reputation in

social media: A dynamic structural model. Journal of

Management Information Systems, (29:2), pp. 41-76.

Tech Times, 2015. Facebook losing teen audience. Now it's

just old people socializing. from: http://

www.techtimes.com, retrieved on January 12, 2016.

Thompson, J. A. 2001. Commitment shift during

organizational upheaval: Physicians’ transitions from

private practitioner to employee. In Academy of

Management Proceedings (1), pp. C1-C6.

Tsai, H. T., and Bagozzi, R. P. 2014. Contribution behavior

in virtual communities: Cognitive, emotional, and

social influences. MIS Quarterly (38:1), pp. 143-163.

Wasko, M. M., and Faraj, S. 2005. Social capital and

knowledge contribution. MIS Quarterly (29:1), pp. 35-

57.

Xu, B., Xu, Z., and Li, D. 2015. Internet aggression in

online communities: A contemporary deterrence

perspective. Information Systems Journal, forthcoming.

Zhang, X., and Venkatesh, V. 2013. Explaining employee

job performance: Role of online and offline workplace

communication networks. MIS Quarterly, (37:3), pp.

695-722.

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

332