Mapping of Terminology Standards

A Way for Interoperability

Sven Van Laere, Frank Verbeke, Frederik Questier, Ronald Buyl and Marc Nyssen

Department of Biostatistics and Medical Informatics – Public Health,

Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Laarbeeklaan 103, 1090 Jette, Belgium

{svvlaere, fverbeke, fquestie, rbuyl, mnyssen}@vub.ac.be

Keywords: Terminology standard, interoperability, eHealth

Abstract: Standards in medicine are essential to enable communication between healthcare providers. These standards

can be used either for exchanging information, or for coding and documenting the health status of a patient.

In this position paper we focus on the latter, namely terminology standards. However, the multidisciplinary

field of medicine makes use of many different standards. We propose to invest in an interoperable electronic

health record (EHR) that can be understood by all different levels of health care providers independent of the

kind of terminology standard they use. To make this record interoperable, we suggest mapping standards in

order to make uniform communication possible. We suggest using mappings between a reference

terminology (RT) and other terminology standards. By using this approach we limit the number of mappings

that have to be provided. The Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine, Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) can

be used as a RT, because of its extensive character and the preserved semantics towards other terminology

standards. Moreover, a lot of mappings from SNOMED CT to other standards are already defined previously.

1 INTRODUCTION

In medical practice a lot of standards are

used (Gaynor, Myung, Gupta, Rawn, & Moulton,

2008), not only for exchanging information between

medical instances, i.e. communication standards, but

also for documenting and coding of medical data, i.e.

terminology standards. In this paper we will focus on

terminology standards and their variety. Different

terminology standards are used, even for referring to

an identical concept: GP’s use the International

Classification of Primary Care, 2nd edition (ICPC-2),

physicians in hospitals use the Systematized

Nomenclature of Medicine, Clinical Terms

(SNOMED CT), coding teams in hospitals use the

International Classification of Diseases and Related

Health Problems, version 10 (ICD-10) for

reimbursement claims, and so on.

Next to the multidisciplinary use of standards by

the various health care providers, we also need to deal

with differing structures in these standards. In this

article we accept the definition of de Lusignan (2005)

who makes a distinction between codes,

classifications, terminologies and nomenclatures.

De Lusignan defined them as follows:

Codes assign a label to a certain concept.

A classification groups concepts together,

defined by a common characteristic.

Terminologies assign labels to a certain

domain.

Nomenclatures assign codes to concepts that

can even be combined to constitute new

complex concepts.

If we look back in history, medical records were

represented only using free text for a long time. The

reason codes became important was since text-based

retrieval is hard. Not much later, the idea of linking

similar clinical ideas together resulted in

classifications. Nowadays terminology standards use

codes that uniquely represent concepts, e.g. code A00

represents the cholera disorder using ICD-10

encoding. Moreover this terminology makes use of

groupings, e.g. the block of codes represented by code

A00 up to A09, represents Intestinal infectious

diseases, the cholera disorder is thus an intestinal

infectious disease.

76

Van Laere S., Verbeke F., Questier F., Buyl R. and Nyssen M.

Mapping of Terminology Standards - A Way for Interoperability.

DOI: 10.5220/0005889700760080

In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Telecommunications and Remote Sensing (ICTRS 2015), pages 76-80

ISBN: 978-989-758-152-6

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Classification concepts have a single relationship

with their direct predecessor; this can be either an is

a relationship or a grouping relationship that is more

generic. For example, the ICD-10 concept J20 with

description “Acute bronchitis” is the parent of the

concept with code J20.0 with description “Acute

bronchitis due to Mycoplasma pneumonia”. In

ICD-10, the textual representation of the codes

expresses the relationship with their parent. Next to

classifications, we have nomenclatures, e.g.

SNOMED CT, that also include more specialized

relationships to express associations such as

laterality, finding site, severity, … Moreover, in

SNOMED CT, if there is a concept that is not yet

included in the standard, one can also rely on its post-

coordinated representation by combining

SNOMED CT concepts (Cornet, Nyström, &

Karlsson, 2013).

Documentation and coding of problems,

diagnoses and treatments is getting more valuable to

work towards an electronic health record

(EHR) (Dickerson & Sensmeier, 2010). The data of

this record should not only be used in a uniform way,

it should also be possible to interpret the EHR in the

same way, from a GP in his medical practice to a

physician in the hospital. In healthcare all providers

work together in order to deliver the best care to the

patient. However, since in the different levels of

healthcare, different terminology standards are being

used with different underlying structures, we should

address the topic on how to align these standards to

make them interoperable.

Often a combination of free text and coded text is

used in patient record documents. Working towards

optimal use of coding inside the health record will

lead to better documentation of the patient’s health

status and eventually more appropriate treatment will

lead to improvement of a patient's health.

This paper proposes to introduce a bridge between

different terminology standards using a reference

terminology (RT). This RT must fulfill the

requirement of being semantic interoperable with

other terminology standards. We will further discuss

how we can work towards this interoperability in

Section 2. We will provide a discussion in Section 3

and give a conclusion in Section 4.

2 MAPPING STANDARDS

Currently, many care providers have to reenter the

same data over and over again. When a patient

contacts a GP for a problem and needs to be referred

to the hospital, the GP’s data is copied by reentering

the data in its appropriate form by the physician in a

hospital. Instead of entering data over and over again,

we propose to introduce a mapping between different

terminology standards.

2.1 Mapping

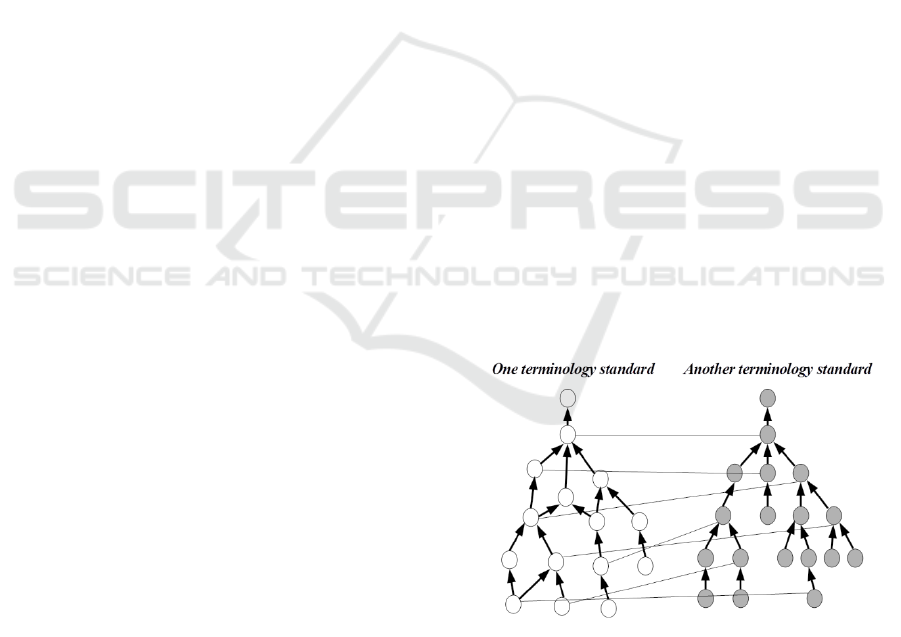

A mapping is a linkage between a concept from one

standard to another standard (see Figure 1) based on

the equivalence between the two concepts. This is not

only done by comparing the syntactical

representation of a concept, i.e. the description of a

concept. We propose to make mappings between

standards, using the following guidelines:

Consider the place in the hierarchy of a

terminology standard;

Consider the semantics of a concept;

Consider the relationship with other

concepts around a concept (if appropriate).

When we apply the process of mapping concepts

of different terminology standards, we do have two

approaches: manual mapping or semi-automatic

mapping. In the manual approach we rely on human

knowledge of medical experts, linguists, terminology

experts… Or we can use a computer algorithm that

queries for candidate mappings based on the lexical

representation of a concept, i.e. the description. After

the candidate mappings are identified, human review

of the automatic mapping is still required to evaluate

the found mappings according to the abovementioned

guidelines. This approach is thus less time consuming

w.r.t. the manual mapping approach where experts

manually identify and validate the mappings.

Figure 1: Mapping from one standard to another.

2.2 Semantic interoperability

In healthcare, interoperability is defined as the state

which exists between two application entities, when

one application entity can accept and understand data

Mapping of Terminology Standard

A Way for Interoperability

77

from the other and perform that task without the need

for extra operator intervention. (Aguilar, 2005)

Interoperability can be established at the level of

semantics, i.e. semantic interoperability. This means

that the information should be understood at the level

of domain concepts.

When links between terminology standards are

established, we ensure translation of one standard to

another is computer processable without losing the

aspect of semantics is possible. The degree of

semantic interoperability then depends on the level of

agreement regarding the terminologies and the

conceptual representation behind it.

In the process of communication between a GP

and a physician, they both are allowed to use their

own proper language (i.e. codes of a terminology

standard). By using mappings we can find the

equivalent concept in the other terminology standard

if a mapping is provided.

2.3 Wide variety of standards

Since a wide variety of medical standards exists and

insufficient effort is invested in e-health standard’s

interoperability, we assume it is worth-while to invest

in providing mappings between different standards.

We propose to do this in a step by step approach as

proposed by the International Health Terminology

Standards Development Organisation (IHTSDO,

2014), since this mapping process will be a time-

consuming effort. Since clinical terminologies

typically consist of several thousands of concept

codes per terminology, we propose to provide

mappings per medical domain, such as cardiology,

nursing, and others instead of mapping the whole

terminology at once. We can then evaluate the

process of mapping one domain and – if successful –

apply it to another domain.

Even if we know the principles for mapping, the

problem of the wide variety of medical vocabularies

still remains:

ICPC-2 classifies patient data and clinical

activities in the domain of general/family

practice and primary care (Verbeke, Schrans,

Deroose, & De Maeseneer, 2006);

ICD-10 is a classification used to monitor the

incidence and the prevalence of diseases and

other health problems (WHO, 2015);

Logical Observation Identifier Names and

Codes (LOINC) is the universal standard for

identifying medical laboratory observations

(McDonald et al., 2003);

NANDA is an international classification used

in the nursing domain (Müller-Staub, Lavin,

Needham, & van Achterberg, 2007);

SNOMED CT is a nomenclature used for

exchanging healthcare information between

physicians and other healthcare providers

(Donnelly, 2006);

…

2.4 Reference terminology

If we apply a mapping from each terminology

standard to another (see Figure 2a), we end up with

𝑁∙(𝑁−1)

2

mappings that are necessary, where N is the

number of standards. We propose the use of a

common reference terminology (RT) from which we

map to each medical standard (see Figure 2b). The

number of mappings needed is then equal to N.

For this reference terminology, it is key to find the

terminology that is the most comprehensive in the

medical domain, containing also concepts from

various domains. SNOMED CT covers more than

310,000 concepts and is likely to be the most

appropriate to use as RT. Moreover, SNOMED CT is

the only standard providing both pre-coordinated and

post-coordinated expressions (Benson, 2010).

Pre-coordination is used when a clinical idea is

represented by a single concept id, e.g. fracture of

tibia is represented by concept id 31978002.

Post-coordinated expressions on the other hand use a

combination of concept ids to represent a concept,

e.g. fracture of the left tibia can be represented as

31978002 : 272741003 = 7771000, that represents

fracture of tibia : laterality = left.

Figure 2a: Mapping each standard to every other standard.

2b: Mapping using a reference terminology (RT)

3 DISCUSSION

In this paper we propose an approach for a more

interoperable health record of the patient. We have to

explore the possibilities of mappings fully in a certain

Fourth International Conference on Telecommunications and Remote Sensing

78

healthcare domain and evaluate the benefits of it. We

propose to use SNOMED CT as a reference

terminology (RT).

At the time of writing an EU project, named

ASSESS CT - Assessing SNOMED CT for Large Scale

eHealth Deployments in the EU (ASSESS-CT, 2015),

is attempting to evaluate the fitness of the

international clinical terminology SNOMED CT as a

potential standard for EU-wide e-health deployments.

Based on the ASSESS-CT project, an evaluation must

be made of the advantages and disadvantages of using

SNOMED CT as potential RT standard for the EU. If

this fitness evaluation turns out negative, we may

need to investigate the possibility of using

another RT.

An argument in favor of using SNOMED CT as a

RT is that there already exists a lot of mappings from

SNOMED CT to other terminology standards:

ICD-10

ICD-10-CM (CM indicates a clinical

modification of the ICD standard)

ICD-9-CM

ICD-O3 (ICD for the oncology domain)

ICPC-2

LOINC

Nursing classifications, such as NANDA, NIC,

ICNP, …

Pharmaceutical classifications such as WHO’s

ATC and the US National Library of

Medicine’s RxNorm

CPT (medical procedure codes)

Another candidate RT is the Unified Medical

Language Systems (UMLS) that was designed and is

maintained by the National Library of Medicine

(NLM) (Humphreys, Lindberg, Schoolman, &

Barnett, 1998). UMLS is a collection of vocabularies

biomedical health sciences already providing the

linkage between them. This system exists of three

knowledge sources: the Metathesaurus, the Semantic

Network, and the SPECIALIST Lexicon and Lexical

Tools. UMLS clusters terms of terminology standards

that are equal in one UMLS concept and assigns them

a unique id. SNOMED CT is also integrated in this

Metathesaurus. Though UMLS does not follow the

semantics of SNOMED CT completely (NLM, 2007).

As stated by Garla and Brandt (2012) the tool support

for using UMLS with respect to SNOMED CT is

more robust, whereas semantic differences within

UMLS may affect the accuracy of similarity

measures. Since the semantics are of utmost

importance, we opt to use SNOMED CT instead.

If we use mappings between terminology

standards, these mappings are not always

bidirectional in use: if a mapping between two

concepts of two terminology standards does exist, this

is not necessarily the case in reverse. For example the

map from SNOMED CT to ICD-10, cannot be

reversed since it is common for many details, and

different SNOMED CT concepts map to a single

ICD-10 code. Reversing the map is not possible since

one ICD-10 code would refer to many different

SNOMED CT concepts.

We believe working together towards a more

integrated EHR, based on a RT, will benefit to the

care of patient. The inter-terminology mapping

should preferably be an automated background

process that is transparent to the health care provider

or EHR user and should not interfere with the routine

clinical documentation practice.

Since the RT will be used in the shared EHR, the

semantics will be implied by the RT. Moreover, by

making use of the mappings, care providers will

always be able to view the content using the

terminology standard that was originally used.

Eventually, more extensive use of a RT will also

create new clinical decision support opportunities

leading to better patient care.

4 CONCLUSIONS

For recording of information in health care, a

combination of free text and coded text is often used.

In order to improve information sharing for the

purpose of patient care or for the management of the

hospital, we should invest in mechanisms enabling

full and transparent use of coded information in the

health record. Most service providers already use one

or more terminology standards. However, across

different service providers different standards are

used. Therefore, sharing information and knowledge

about the patient often does not happen in an

interoperable way.

This paper proposes a reference terminology

based mapping approach in order to meet this

requirement. A reference terminology (RT) has the

advantage of limiting the number of mappings that

must be made. The proposed RT is SNOMED CT,

because it is the most extensive medical terminology

in use, it supports both pre- and post-coordination and

the semantics are preserved with respect to other

terminology standards. Another reason for choosing

SNOMED CT is the amount of resources that are

available. There already do exist a lot of mappings

from SNOMED CT to other terminology standards,

respecting the accuracy of similarity metrics between

different terminology standards.

Mapping of Terminology Standard

A Way for Interoperability

79

Sufficient effort should be invested in making the

mappings database more complete. This is a time

consuming process and therefore a step by step

approach is suggested. Start by testing the idea in one

domain and then apply it in another one. Eventually

this will lead to a shared EHR ensuring

interoperability between care providers. Large

collections of structured data related to patient health

status and health care provider activity can ultimately

contribute to EHR systems capable of providing

clinical decision support.

REFERENCES

Aguilar, A. 2005. Semantic Interoperability in the Context

of e-Health. In CDH Seminar ’05, Galway, Ireland.

ASSESS-CT. 2015. ASSESS CT - Assessing SNOMED CT

for Large Scale eHealth Deployments in the EU.

Available from: http://www.assess-ct.eu

Benson, T. 2010. SNOMED CT. In Benson, T. (ed.),

Principles of Health Interoperability HL7 and

SNOMED (pp. 189–215). doi:10.1007/978-1-84882-

803-2

Cornet, R., Nyström, M., & Karlsson, D. 2013. User-

directed coordination in SNOMED CT. In C. U.

Lehmann, E. Ammenwerth, & C. Nøhr (Eds.), Studies

in Health Technology and Informatics (Vol. 192, pp.

72–76). doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-289-9-72

De Lusignan, S. 2005. Codes, classifications, terminologies

and nomenclatures: definition, development and

application in practice. Informatics in Primary Care,

13(1), 65-70. Retrieved from:

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/ content/bcs/ipc

Donnely, K. 2006. SNOMED-CT: The advanced

terminology and coding system for eHealth. Studies in

Health Technology and Informatics, 121, 279-290.

Dickerson, A.E. & Sensmeier, J. 2010. Sharing data to

ensure continuity of care. Nursing Management, 41(7),

19-22. doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.0000384142.04693.58

Garla, V.N. & Brandt, C. 2012. Semantic similarity in the

biomedical domain: an evaluation across knowledge

sources. BMC Bioinformatics, 13, 261-273.

doi:10.1186/1471-2105-13-261

Gaynor, M., Myung, D., Gupta, A., Rawn, J., & Moulton,

S. 2008. Interoperability of medical applications and

devices. In R. H. Sprague Jr. (Ed.), Proceedings of the

41st Hawaii International Conference on Systems

Science, 7-10 January 2008, Waikoloa, Big Island, HI,

USA. doi:10.1109/HICSS.2008.217

Humphreys, B. L., Lindberg, D. A. B., Schoolman, H. M.,

& Barnett, G. O. 1998. The Unified Medical Language

System: An Informatics Research Collaboration.

Journal of the American Medical Informatics

Association, 5(1), 1-11.

doi:10.1136/jamia.1998.0050001

IHTSDO. 2014. Mapping to SNOMED CT. Discussion and

Guidance on Mapping Based Solutions Design for

Migration or Transformation. Available from

https://csfe.aceworkspace.net/sf/go/doc10065

McDonald, C.J. et al. 2003. LOINC, a Universal Standard

for Identifying Laboratory Observations: A 5-Year

Update. Clinical Chemistry, 49(4), 624-633.

doi:10.1373/49.4.624

Müller-Staub, M., Lavin, M. A., Needham, I., & van

Achterberg, T. 2007. Meeting the criteria of a nursing

diagnosis classification: Evaluation of ICNP®, ICF,

NANDA and ZEFP. International Journal of Nursing

Studies, 44(5), 702-713.

doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.02.001

NLM. 2007. Insertion of SNOMED CT® into the UMLS®

Metathesaurus®: Explanatory Notes. Available from

https://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/

umls/Snomed/snomed_represented.html

WHO. 2015. International Classification of

Diseases (ICD). Available from http://www.who.int/

classifications/icd/en/.

Verbeke, M., Schrans, D., Deroose, S., & De Maeseneer, J.

2006. The International Classification of Primary Care

(ICPC-2): an essential tool in the EPR of the GP.

Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 124,

809–814. doi: 10.3233/978-1-58603-647-8-809

Fourth International Conference on Telecommunications and Remote Sensing

80