Lido – Wiki based Living Documentation with Domain Knowledge

Reuven Yagel

Software Engineering Department, Azrieli - The Jerusalem College of Engineering, POB 3566, 9103501 Jerusalem, Israel

Keywords: Living Documentation, Domain Knowledge, Wiki, Software Processes.

Abstract: There is a gap between code and documentation in many software development projects. This gap usually

grows as time goes by, decreasing developers ability to keep product quality high. We describe how

documentation based on a common wiki can be enhanced with domain knowledge in ways that ensure better

live documentation. This way updated and relevant documentation, i.e., specifications, manuals, models,

test scripts, etc. lead ultimately to higher quality software.

1 INTRODUCTION

A software product is composed of source code and

compiled executables but also of data and

documentation in various forms and formats. Today,

wiki (Wikipedia) applications have become a

popular means for documenting software and many

other areas. Wikipedia.com is a notable popular

example.

In software development it is even more

common, especially in open source projects, to use

wiki for documentation. Actually, the first wiki site,

WikiWikiWeb was used for documenting a software

project (http://c2.com/cgi/wiki?WikiHistory).

Using wiki for documentation is in itself a big

step towards a documentation that has more chances

to be updated and relevant throughout a software

project lifecycle, due to its accessibility. But, can we

do better?

In previous works (Exman et al., 2014; Yagel,

2011) it was shown how executable specifications

(Adzic, 2009) can be augmented with domain

concept modifiers in order to (semi-) automatically

create parts of the code. Here we lay a plan to

broaden the scope to documentation as a whole. By

software documentation we mean here all forms of

written text and other documents that accompany the

software code itself. Documents can range from

requirement and design/architecture specifications,

modeling diagrams, test scripts, glossaries, technical

and user manuals, various logs of formal and

informal communication between various project

members and stakeholders (even e.g. marketing),

down to source code comments.

1.1 The Problem – The Gap between

Documentation and Code

The problem is the gaps that often exist between

various documentation artifacts and the code. This

gap usually grows as software is being development

due to lack of continuous updates and changes

which are often not reflected back to the

documentation – thus making it obsolete.

For example, it is common to draw design

diagrams, e.g. in UML (Fowler, 2003), in earlier

phases of a project. Let's say this is a class diagram

with some domain concepts. Later on when these

classes are implemented (sometimes partially

generated by a tool), reality comes in and the design

changes due to, e.g., new insights gained while

developing the system or requirement changes. What

happens then to the original diagram? In case we

still need it for documenting the design – how do we

keep it updated in a maintainable and economic

way? Can we provide methods and tools for creating

documentation in which developers will be more

productive, in contrast to today's general negative

attitude to documentation?

1.2 Live Documentation

We roughly define live documentation as a set of

documents which are actively synced with changes

in software code. The term living documentation is

widely discussed in an upcoming book in

preliminary edition with this title (Martraire, 2016).

Previously, executable specifications were

26

Yagel, R..

Lido – Wiki based Living Documentation with Domain Knowledge.

In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Software Knowledge (SKY 2015), pages 26-30

ISBN: 978-989-758-162-5

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

mentioned as a form of living documentation, e.g. in

(Adzic, 2011; Smart, 2014).

The main idea is that the documentation is

coupled to the source code by connecting it to the

toolchain used to develop the code itself and that it

is as accessible as the code.

Going back to the UML class diagram example,

it will be considered a living diagram if it can be

automatically updated following a corresponding

change in code and vice versa.

1.3 Why Wiki?

Using wiki for documentation has several

advantages. First it is a proven and acceptable tool

for collaboration. Its simplicity and high

accessibility, usually through common browsers,

makes it an attractive target. It is also based on plain

text which makes it also easy to manipulate by

programs. It's free from helps and directs the

developers/engineers to work in higher level of

abstraction, away from the formality and constraints

of today's programming languages. Above all,

markdown is a simple way to mark and link

concepts, models and other various levels of

software artifacts. In this work we emphasize wiki as

a common base for most of the practices or methods

of software documentation.

1.4 Related Work

FitNesse (Adzic, 2008) is a wiki-based web tool for

non-developers to write formatted acceptance tests

through tabular example/test data.

BDD (Behavior Driven Development) (North,

2006), is an extension of TDD (Test Driven

Development/Design) aiming at writing

requirements by non-technical stakeholders.

Cucumber (Wynne and Hellesoy, 2012) and

SpecFlow (SpecFlow) are tools which accept stories

written in a somewhat constrained natural language,

directly supporting BDD. They are easily integrated

with unit testing and user/web automation tools.

Here (Yagel, 2011) we reviewed these practices and

tools.

DaSpec (DaSpec) is a new tool that uses wiki for

writing executable specifications in free form and

exercises the system under test for

approval/acceptance. BDDfy (BDDfy) is a tool that

creates documentation from unit tests written in

some disciplined manner, thus reserving the usual

order and generating documentation from lower

levels.

In the diagramming area, many tools are

generating source code from, e.g., UML diagrams.

Some of them use standard formats, e.g. XMI files

used by ArgoUML (ArgoUML). Some of the tools

also support reverse engineering for creating or

updating those diagrams, following changes in the

code – thus helping keep the documentation

updated.

Mapador (Mapador) is a service for

automatically extracting documentation from code,

which targets writing documentation as part of the

development process and not a posteriori.

ATDD (Acceptance Test Driven Development)

is an extension of TDD, also known as Agile

Acceptance Testing (Adzic, 2008). Further

extensions are Story Testing, Specification with

examples (Adzic, 2011) or Living/Executable

Documentation (Brown, 2011; Smart, 2014).

The mentioned coming book (Martraire, 2016)

emphasizes these relevant practices: Living

Diagram, Living Glossary, Declarative Automation,

Enforced Guidelines, Small-Scale Model and others.

For example, the book discusses how using

Javadoc's DocLet (documentation generator), one

can parse source files for annotations marking main

domain concept and then generating a glossary

document.

Concerning diagrams, there are libraries and

services which accept as input simple text format

and can then generate diagram documentation. See

for example: yuml.me, diagrammr.com, and

structurizr.com. More general legacy tools can be

used too, e.g. Graphviz (Graphviz) that uses .dot file

format for generating graphs.

Enterprise/ALM tools like IBM's Rational Team

Concert (IBM) put emphasis on traceability which is

important to link the various documentation and

software levels.

More generally, the emphasis on domain analysis

follows the Domain Driven Design (DDD) work

(Evans, 2003). Even at higher level of abstraction

we can make use of ontologies to guide the

documentation and development process, as

discussed at (Feathers, 2004; Osetinsky and Yagel,

2014).

Wiki Software. It is now common that project

management tools, version control systems and

services offer built-in wiki support. Github (Github)

(a well-known version control cloud service) for

example is adding a wiki by default to every new

code repository (see: https://help.github.com/

articles/about-github-wikis/). However, in contrast

to our proposal in this paper, this wiki is managed

separately from the code (e.g. in terms of security

policies and git versioning). It is also a common

Lido – Wiki based Living Documentation with Domain Knowledge

27

practice for a github project (and other similar ones)

to have a README file at the source root, which

often serves as the main page for all other

documentation. There are many (mostly open

source) wiki engines, e.g. MediaWiki (MediaWiki)

that powers Wikipedia and other wikis.

Semantically Enhanced Wikis are a major step

towards better integration of wiki content. A notable

example is Semantic MediaWiki (MediaWiki) which

is an extension to MediaWiki which allows

semantically annotating wiki pages, using structural

information, ontology languages, semantic web and

alike. In this work we focus more on the usability

side of integrating various tools under a wiki, and

indeed such semantic tools naturally fit in.

The remaining of this paper is organized as follows:

In Section 2 we discuss the general approach, in

section 3 we give a preliminary example and then in

section 4 we conclude with some remarks and future

work.

2 THE SOLUTION – ENHANCED

WIKI

2.1 Enhanced Wiki

The main idea is to use wiki as the "center of mass"

for software documentation. We want to build on the

existing wide wiki engines and tools, especially

dedicated parsers and generators (as mentioned

above in section 1.4) to keep the documentation and

the code in sync. Various documentation tools will

be plugged into the wiki ecosystem.

The case study in the next section will use, as a

starting point, a new tool that uses a wiki for

working with executable specifications. We intend

to extend the approach of such a tool into using a

non-fixed set of tools and methods (abbreviated Lido

for Living Documentation) for producing various

kinds of documentation.

In particular, we suggest marking domain

concepts in the wiki in such a way the various

documentation tools will detect those concepts and

help generate more meaningful documentation.

A suggested workflow for working in this way,

is as follows:

a. Executable Specification – one writes an

executable specification in a wiki (using standard

Markup),

b. Domain Annotation – using markup special

syntax to mark domain and software related

entities (e.g. using DDD vocabulary),

c. Diagram Generation – using the entities above,

possibly with other added information, e.g.

connection between entities, generating diagrams

(e.g. in UML),

d. Connection of Specifications to Tests –

underneath, step definitions are generated which

connect sentences from the specification to tests

which exercise the system under test,

e. Run Results – finally the result of this run appear

in a web page

f. Coding – implementing in a programming

language the missing parts,

g. Updating and Iterating – continuously evolving

the code and the documentation up to the point

of a successful release.

Other steps are possible too, as will be demonstrated

in the next section. Also, the order is not necessary

and should be adapted and customized to the

development methodology in use.

The main contribution of this paper is gathering

various tools under the umbrella of wiki to achieve

really live documentation.

3 A CASE STUDY:

BLACK-LISTING

APPLICATION

We demonstrate here our method by combining the

basic techniques of our previous approach to

executable specifications (Exman et al., 2014;

Yagel, 2011; Yagel et al., 2013) with the approach

of the above referred tool DaSpec (DaSpec).

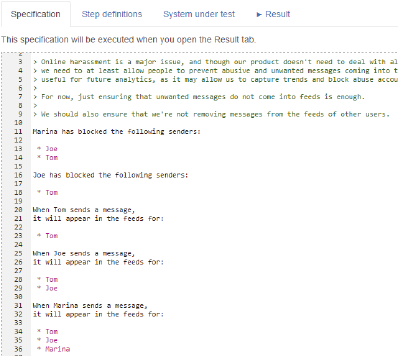

Figure 1: Executable Specification.

SKY 2015 - 6th International Workshop on Software Knowledge

28

We suggest expanding the idea of using wiki for

writing executable specifications into a suite of

living documentation techniques.

We extend here an example of a black listing

application. Here we demonstrate some of the steps

described above. In Figure 1 we see an executable

specification – taken from DaSpecs' documentation

site (http://daspec.com/examples/basic/checking_

for_missing_and_additional_list_items/, the actual

purpose is to demonstrate working with list of

items).

Figure 2: Annotating Domain Concepts.

We can enrich this specification in several ways.

We shall give the following methods:

a. Mark Domain Concepts – here we use bold

Markdown syntax (**) to mark concepts of the

target domain – Figure 2.

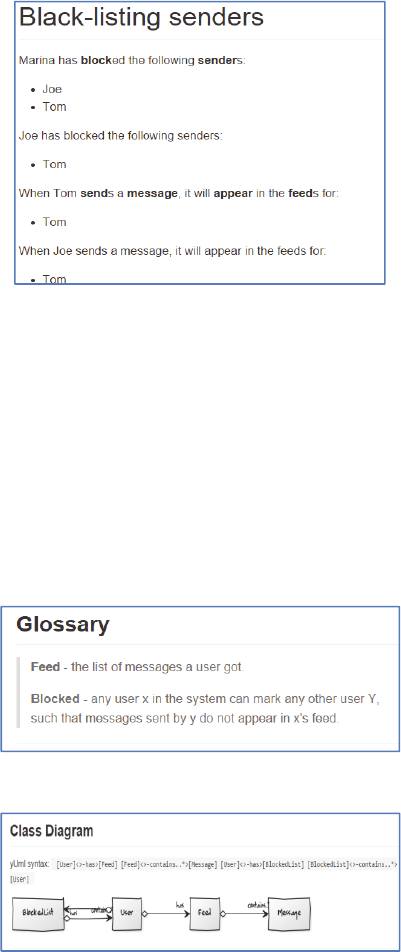

b. Glossary – add a glossary part to the wiki which

can then be output in different formats – Figure

3.

c. Class Diagram – use text syntax to generate a

class diagram – Figure 4.

Figure 3: Glossary.

Figure 4: Class Diagram.

See also our previous work (Exman et al., 2014)

for a thorough discussion about finding entities in

executable specifications.

4 DISCUSSION

We have given preliminary ideas how wiki can serve

as a basis for more meaningful documentation.

Some documentation types need extra syntax not

covered by common Markup, the UML class

diagram is an example for that.

Wiki software saves also the history of edits, in

order to take advantage of it, custom diffs, e.g.

graphic diff, might be needed as well.

We need to be careful not to constrain ourselves

to the wiki medium in a way that will harm other

useful kinds of documentation. For legacy systems it

might be too extensive to convert existing

documentation, for example a specification is given

in a Doc file format.

Traceability between documents themselves and

between the source code is still an open issue that

can be further investigated.

In the spirit of this work we believe that

documentation wiki should be an integral part of the

configuration management of a project, in order to

be better integrated and influencing.

4.1 Future Work

We plan to further extend previous work (Exman et

al., 2014) and also use mark-up based executable

specification augmented by domain annotations, as

well as integrating ontology repositories. Then,

combining various tools in coherent ways, as much

as possible.

We aim for building a framework for better

integration of the discussed wiki tools. This will also

allow to measure and compare the success and

impact of various tools and the whole process.

4.2 Main Contribution

By having better tools we can expect from software

developers to create better documentation and work

in higher levels of abstraction. Ultimately, this can

lead to working only in those higher and more

human oriented levels, automating the rest of the

work.

Lido – Wiki based Living Documentation with Domain Knowledge

29

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Iaakov Exman for the fruitful

discussion and collaboration. And also the

anonymous reviewer who pointed out semantic wiki

and other useful comments.

REFERENCES

Adzic, G., 2008. Test Driven .NET Development with

FitNesse, Neuri, London, UK.

Adzic, G., 2009. Bridging the Communication Gap:

Specification by Example and Agile Acceptance

Testing, Neuri, London, UK.

Adzic, G., 2011. Specification by Example – How

Successful Teams Deliver the Right Software,

Manning, New York, USA.

ArgoUML. Available from: http://argouml.tigris.org/. [29

September 2015].

BDDfy. Available from: https://github.com/

TestStack/TestStack.BDDfy. [29 September 2015].

Brown, K., 2011. Taking executable specs to the next

level: Executable Documentation, Available from:

http://keithps.wordpress.com/2011/06/26/taking-

executable-specs-to-the-next-level-executable-

documentation/. [1 September 2011].

DaSpec. Available from: http://daspec.com/. [29

September 2015].

Evans E., 2003. Domain-Driven Design: Tackling

Complexity in the Heart of Software. Prentice Hall.

Exman I., Litovka, A. and Yagel, R., 2014. Ontologies +

Mock Objects = Runnable Knowledge, the 5th

International Conference on Knowledge Discovery,

Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management

(IC3K) - SKY Workshop, Rome, Italy.

Feathers M., 2004. Working Effectively with Legacy Code.

Prentice Hall, 2004.

Fowler M., 2003. UML distilled, 3rd ed., Addison Wesley.

Github. Available from: https://github.com/. [29

September 2015].

Graphviz. Available from: http://www.graphviz.org/. [29

September 2015].

Krötzsch M., Vrandecic D., Völkel M., Haller H., Studer

R., 2007. Semantic Wikipedia. In Journal of Web

Semantics 5/2007, pp. 251–261. Elsevier.

IBM. Rational Team Concert. Available from:

http://www-03.ibm.com/software/products/en/rtc. [29

September 2015].

Mapador. Available from: http://www.mapador.com/

documentation/. [29 September 2015].

Martraire C., 2016. Living Documentation - A low-effort

approach of Documentation that is always up-to-date,

inspired by Domain-Driven Design. Leanpub

(expected). http://leanpub.com/livingdocumentation.

MediaWiki. Available from: https://www.mediawiki.org/.

[29 September 2015].

North, D., 2006. Introducing Behaviour Driven

Development, Better Software Magazine. Available

from: http://dannorth.net/introducing-bdd/. [29

September 2015].

Osetinsky I, and Yagel, R., 2014. Working More

Effectively with Legacy Code Using Domain

Knowledge and Abstractions – A Case Study, the 5th

International Conference on Knowledge Discovery,

Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management

(IC3K) - SKY Workshop, Rome, Italy.

Smart J. F., 2014. BDD in Action Behavior-Driven

Development for the whole software lifecycle,

Manning.

SpecFlow. Pragmatic BDD for .NET. Available from:

http://specflow.org. [29 September 2015].

Wynne, M. and Hellesoy, A., 2012. The Cucumber Book:

Behaviour Driven Development for Testers and

Developers, Pragmatic Programmer, New York.

Wikipedia. Available from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wiki. [29 September

2015].

Yagel, R., 2011. Can Executable Specifications Close the

Gap between Software Requirements and

Implementation?, pp. 87-91, in Exman, I., Llorens, J.

and Fraga, A. (eds.), Proc. SKY'2011 Int. Workshop on

Software Engineering, SciTePress, Portugal.

Yagel, R., Litovka, A. and Exman I., 2013: KoDEgen: A

Knowledge Driven Engineering Code Generating

Tool, The 4th International Conference on Knowledge

Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge

Management (IC3K) - SKY Workshop, Vilamoura,

Portugal.

SKY 2015 - 6th International Workshop on Software Knowledge

30