LEADER EU Program and Its Governance

A Fuzzy Assessment Model

Luca Anzilli, Gisella Facchinetti, Giovanni Mastroleo and Alessandra Tafuro

Department of Management, Economics, Mathematics and Statistic, University of Salento,

via per Monteroni, 73100 Lecce, Italy

Keywords:

EU Agricultural Programs, Leader, LAG, Governance, Fuzzy Systems.

Abstract:

In regard to the LEADER program (European Union initiative for rural development), in the paper the authors

propose a model for assessing the governance system of Local Action Groups (LAGs) in terms of structure,

decision making processes and principles that ensure a clear and transparent activity thus creating significant

value for the community. Governance, in particular, is a highly important theme when it evaluates the impacts

of LEADER measures: if the quality of their governance is high, they could contribute to make the rural

development process more efficient in each region of EU. The empirical literature on this subject is not well

developed and the authors hope and expect that this new assessment model will produce important ideas for

making governance of the LAGs more effective. It is based on a Fuzzy Expert System and here are presented

results for Puglia (Italy) LAGs.

1 INTRODUCTION

In this paper the authors propose a fuzzy inference

system (Siler and Buckley, 2005; Castillo and Al-

varez, 2007; Leondes, 1998; Pedrycz and Gomide,

2007) to face the governance evaluation of an impor-

tant European Union initiative for rural development

called LEADER Program. LEADER (“Liaison Entre

Actions de D´eveloppement de l’

´

Economie Rurale”,

meaning “Links between the rural economy and de-

velopment actions”) is a local development method

which allows local actors to advance an area by using

its endogenous production potential. The LEADER

approach forms one of the four axes of Rural

Development Policy (http://enrd.ec.europa.eu/enrd-

static/leader/en/leader en.html). LEADER projects

are managed by Local Action Groups (LAGs). Each

project must involve a relatively small rural area,

with a population of between 10,000 and 100,000.

LEADER has three objectives (Brinkerhoff, 2007;

Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, 2011; Kersbergen and

Waarden, 2004; Koppell, 2010):

• to encourage experiments in rural development;

• to support cooperation between rural territories:

several LAGs can share their resources;

• to network rural areas, by sharing experiences and

expertise in the development of rural areas by cre-

ating databases, publications and other modes of

information exchange.

Moreover, as some 14% of the population in the EUs

predominantly rural regions suffers from employment

rates of less than half the EU average and there are ar-

eas of low per-capita GDP, much can be done to help

create a wider variety of better quality jobs and an im-

proved level of overall local development, including

through information and communication technologies

(ICT). Every LAG is made up of public and private

partners from the rural territory and must include rep-

resentatives from different socio-economic sectors.

They receive financial assistance to implement local

development strategies, by awarding grants to local

projects. They are selected by the managing author-

ity of the Member State, which is either a national,

regional or local, private or public body responsible

for the management of the programme. In this paper

we focalize our attention to the LAG Governance as

it is a highly important theme when we want evalu-

ate the impacts of LEADER measures. Many studies

have highlighted quantitative outputs - such as diver-

sification into activities, total volume of investments,

a number of micro-enterprises which are supported or

created, a number of projects which are financed, a

number of beneficiaries which are supported, and a

large number of jobs which are created but these indi-

cators will provide a limited insight. For this reason, it

Anzilli, L., Facchinetti, G., Mastroleo, G. and Tafuro, A..

LEADER EU Program and Its Governance - A Fuzzy Assessment Model.

In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence (IJCCI 2015) - Volume 2: FCTA, pages 121-130

ISBN: 978-989-758-157-1

Copyright

c

2015 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

121

is important to supplement the quantitative indicators

with qualitative indicators which provide information

on the multi-dimensional character of LAGs gover-

nance. By combining the information it is possible to

assess how the functioning of LAGs governance sys-

tem contributes, directly or indirectly, to achieve the

desired outcomes such as the development of a rural

area. The evaluation of governance can involve an as-

sessment of both the process (how it is functioning)

and the outcomes (impacts on the rural area). The au-

thors have tried to evaluate the LAG governance sys-

tem in terms of structure, decision making processes

and principles that ensure a clear and transparent ac-

tivity and create significant value for the community.

We have adopted a series of drivers that will con-

tribute to the setting-up of a conceptual framework for

the evaluation of LAG governance. It should be clear

that good governance is an ideal which is difficult to

achieve in its totality. A number of variables have

a significant impact on what constitutes good gover-

nance. The structure of the conceptual framework is

readable as a tree and starts with three key aspects that

form the first level of branches. They are:

• the nature of members of the partnership (actors);

• the principles that guide the collaboration and the

involvement of the partners in the decision mak-

ing process (decision making);

• the accountability and transparency of LAG’s ac-

tivities to the stakeholders (transparency).

Within the wider analysis of governance there is a

clear need to focus on the tree macro sectors we have

fixed before. The actors concept is the fruit of an ag-

gregation of the role and the interest shown by Public

Administration and the corporate bodies of the firms

involved. Looking at decision making we have to con-

sider even the synergy between stakeholders, conflicts

of interests and the independence. For transparency

we have to look to internal monitoring and internal

evaluation, transparencyand accountability (Lowndes

and Skelcher, 1998; Shaoul et al., 2012). For each of

these aspects it is important to develop a set of indica-

tors which are the key aspects of the second level. The

indicators may help to uncover further aspects of good

governance due to their fine detail. Each indicator al-

lows the evaluators to determine how close they are

to meeting the standards. The combination of these

indicators can be used to provide an estimate of the

governance of each Local Action Group. To reach

this goal we propose a Fuzzy Expert System (FES)

for several reasons. The problem to propose a LAG

Governance evaluation is a Multi-Attribute Decision

Making (MADM) problem. In fact there are several

aspects we have to take into account to have an aggre-

gated evaluation. The several inputs, that aggregated

offer the final value, hail from a questionnaire that a

research group of University of Salento has submit-

ted to members of several LAGs in Puglia, but this

tool did not provide a satisfactory result. For this rea-

son we propose this different method. The study we

propose is a multidisciplinary problem. Persons and

experts of different areas of expertise are necessary

to focalize all the attributes that this type of evalu-

ation involves. The classical method to elaborate a

questionnaire is a simple statistical average, while the

rules buildings of a FES need of a strong collabora-

tion between mathematicians and researchers of LAG

Governance. As last aspect, a FES may involve qual-

itative and quantitative information. In this way the

experts, more easily, may present their judgements in

a verbal form. We know that this type tool is born

for engineering applications while only few results we

know in economics, finance, management and social

sciences fields, but we think that its potential is so

wide to offer the possibility to expand its action areas

(Anzilli et al., 2013; Lalla et al., 2008; Magni et al.,

2001; Addabbo et al., 2007; Addabbo et al., 2009;

Lalla et al., 2005; Magni et al., 2004; Forte et al.,

2003). In Section 2 we present Leader and LAGs

characteristics in Section 3 we define a LAG gover-

nance and what it is necessary for its evaluation. In

Section 4 we present our model based on a Fuzzy Ex-

pert System. In Section 5 we present our results and

in Section 6 the conclusions.

2 LEADER AND LAG

LEADER program acts as a catalyst in spreading a

new form of territorial governance that can be seen

as a system of interdependence and interaction among

various stakeholders in order to meet the challenges in

public action (OECD, 2013, p.241). In the LEADER

model, local entities play a key role in rural devel-

opment, reflecting the emphasis that the EUs policy

has towards local potential development, program-

ming, partnership and subsidiarity principles (West-

holm et al., 1999; Bache, 2007; Commission, 2012;

Jacoby et al., 2014; Batory and Cartwright, 2011).

In line with these principles, a distinctive feature

of LEADER is the local public-private partnership

– called Local Action Group (LAG) – which is in

charge of coordinating the design of the local devel-

opment strategy as well as its implementation through

the engagement of endogenous, material and intangi-

ble resources, to produce sustainable local develop-

ment. Partnership processes play a central role in the

emergent culture of governance which is now receiv-

FCTA 2015 - 7th International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

122

ing a great theoretical attention. The adoption by the

local authority of a model of policy making focused

on public-private partnership is now at the base of the

processes of growth and competitiveness of each re-

gion so much so that – as (Jones, 2000) argued – the

partnership has become a key component for address-

ing substantive issues of governance at local levels.

Local governance requires, therefore, the interaction

of different players and involves civil society organi-

zations and the private sector in partnership with gov-

ernment for the setting of priorities, the adoption of

policies and the allocation of resources. A process of

this type reflects the interdependence among the part-

ners: this means that the partnership becomes nec-

essary because no entity can achieve its goals with-

out a significant degree of support from the others

(Emerson et al., 2012). Through these networks, gov-

ernments seek the co-operation of partners from the

private sector and civil society in the pursuit of var-

ious objectives, from stimulating economic develop-

ment to promoting social cohesion. Following this

organizational system, the territory is administered

on the basis of a bottom-up programming approach,

which involves all entities of the territory and recon-

ciles the interests of all stakeholders at different level

(Stephenson, 2013).

The membership of the strategic LAG will reflect the

aims of the LEADER Initiative regarding the involve-

ment of community representatives. So it is necessary

to have a balance of statutory, private and community

representation. LAGs need to be balanced and repre-

sentative of the area, genuinely locally based and to

have an accepted structure and method of operation.

It is therefore understandable that the local partner-

ship will be more successful in this task, if the varied

representation of local parties is well mirrored in the

composition of the deliberating and decision-making

bodies. A LAG should include both public and private

partners, and should be well-balanced with represen-

tation from all existing local interest groups, drawn

from the different socioeconomic sectors in the area.

Article 62 of Regulation (EC) No. 1698/2005 stated

that at the decision making level, the economic and

social partners, as well as other representatives of the

civil society, such as farmers, rural women, young

people and their associations, must make up at least

50% of the local partnership. In the LEADER world,

the 50% limit for public partners in the decision-

making bodies of the LAG has brought forth various

solutions. In fact, there is no general recipe and all

depends on the specificities of the socioeconomic and

governance context. Partnership within governance is

not a static principle but it is a subtly changing con-

cept. There is no general rule on the formal set up

of a LAG. It should be a juridical entity of its own

right, but it can take on the form of a no-profit or-

ganization as well as that of a limited business com-

pany. This should be handled with a maximum of

pragmatism and adaptation to local circumstances. In

a partnership, an important role should be played by

local and territorial entities – e.g. municipalities or

regional government – although their presence, some-

times, is only formal and not substantive. Related to

this aspect, a real problem is the limited competence

skills that characterize the administration managers of

the Public Administration (PA), especially regarding

the level of knowledge of EU programs or the un-

derstanding of the LEADER approach. Closely re-

lated to these aspects is the degree of interest in joint

and synergistic programming by the PA that, in many

cases, can depend on the interest expressed by the

politicians. There are some cases in which the pri-

vate and no-profit members of a partnership declare

to find difficulties in creating and maintaining a rela-

tionship with the PA and, in other cases, they point

out the opportunity available in activating new forms

of organizational coordination.

3 A MODEL FOR THE

ASSESSMENT OF THE LAG

GOVERNANCE

Governance is a highly important theme when it eval-

uates the impacts of LEADER measures (Tafuro,

2013). Many studies have highlighted quantitative

outputs - such as diversification into activities, total

volume of investments, a number of micro-enterprises

which are supported or created, a number of projects

which are financed, a number of beneficiaries which

are supported, and a large number of jobs which are

created but these indicators will provide a limited in-

sight. For this reason, it is important to supplement

the quantitative indicators with qualitative indicators

which provide information on the multi-dimensional

character of LAG’s governance. By combining the

information it is possible to assess how the function-

ing of LAG’s governance system contributes, directly

or indirectly, to achieve the desired outcomes such as

the development of a rural area. The evaluation of

governancecan involvean assessment of both the pro-

cess (how it is functioning)and the outcomes (impacts

on the rural area). The authors have tried to evaluate

the governance system of LAG in terms of structure,

decision making processes and principles that ensure

a clear and transparent activity and create significant

value for the community. We have adopted a series of

LEADER EU Program and Its Governance - A Fuzzy Assessment Model

123

drivers that will contribute to the setting-up of a con-

ceptual framework for the evaluation of governance

of LAG. It should be clear that good governance is

an ideal which is difficult to achieve in its totality.

A number of variables have a significant impact on

what constitutes good governance. The structure of

the conceptual framework incorporates nested dimen-

sions and their respective component. The examina-

tion of the governance process is based on three key

aspects of the first level. They are:

• the nature of members of the partnership;

• the principles that guide the collaboration and

the involvement of the partners in the decision-

making process;

• the accountability and transparency of LAG’s ac-

tivities to the stakeholders.

Within the wider analysis of governance there is a

clear need to focus on the whole partnership concept,

to consider not only the issues of the formation, mem-

bership, and power relations among partners, but also

the principles that guide collaboration and the degree

of involvement of the partners in the decision-making

process and the importance of reporting LAGs activi-

ties to the stakeholders. For each of these aspects it is

important to develop a set of indicators which are the

key aspects of the second level. The indicators may

help to uncover further aspects of good governance

due to their fine detail. Each indicator allows the eval-

uators to determine how close they are to meeting the

standards. The combination of these indicators can be

used to provide an estimate of the governance of each

Local Action Group.

3.1 The Principles that Guide the

Collaboration and Degree of

Involvement of the Partners in

Decision-making Process

Since governance is the process by which decisions

are implemented, an analysis of governance focuses

on the principles (i.e. collaboration and degree of

the involvement of the partners in decision-making

process) that have been set to make and implement

the decisions and on the procedures to guide the de-

cision body in decision-making (i.e. how decisions

have to be submitted for approval, modified, agreed

upon; etc.). Governance establishes how the power is

distributed among the members and the influence ex-

erted by each member in the course of decision mak-

ing. When we talk about participation, on the one

hand, we mean the degree of involvement of each

member in the decision making process, but on the

other hand, it is fundamental to consider the existence

of a great synergy among the main stakeholders in

the phases of design and implementation of the ini-

tiatives. By governance, in fact, we mean the selec-

tion of the activities that the LAGs partnership intends

to realize, the role of each member in the implemen-

tation of needed projects, the control of the resources

available, and how the output is distributed among the

participants. Rural policies that follow the LEADER

approach should be designed and implemented in a

way best adapted to the needs of the communitiesthey

serve. One way to ensure this is the implementation of

public consultation processes by which all local stake-

holders are invited to take the lead or participate in

the choices made and, above all, sustaining consulta-

tions and dialogues among the stakeholders. In this

way the objectivity of the decision making process is

guaranteed. At this point, we also have to reflect on

the particular difficulties emerging from the presence

of multiple members in the partnership. In this situa-

tion, heterogeneousinterests and powerof local stake-

holder coexist: which is the source of complexity in

the choice of objectives that the LAG should fix; and

this is also a cause of conflicts of interest that some-

times may create delays in decision-making, as it of-

ten happens, for example in the case of the appoint-

ment of the Technical Management Group. Another

feature of the decision-making process is its indepen-

dence. The accountability and transparency of activ-

ities to stakeholders. Accountability is a key require-

ment of good governance, while transparency refers

to the free flow of information on government pro-

cesses, decisions, requirements and reports (Shaoul

et al., 2012). It allows stakeholders to know what is

happening and to participate meaningfully in various

ways. All stakeholders, in fact, want to know how

well a governance system supports the achievement

of established goals and they also want to see how the

results achievedcompare with the effort and resources

used in obtaining the objectives. For this reason it is

important that some mechanisms of internal monitor-

ing and self-evaluationexist in the LAG and that these

mechanisms are used to ensure the monitoring of dif-

ferent aspects, such as the effectiveness and appropri-

ateness of the work done by the Steering Committee,

the effectiveness and efficiency of animation activities

or, in general, the effectiveness of the LAG in produc-

ing the best possible results using the resources in the

best possible way. To understand and monitor insti-

tutions and their decision-making processes it is im-

portant to have direct access to all relevant informa-

tion. The transparency of information and of the de-

cision making process - including procedures of con-

sultation and participation - are tools used to promote

FCTA 2015 - 7th International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

124

nonarbitrary and responsive decisions. Transparency

is built on the free flow of information and is based

on the existence and use of mechanisms to guaran-

tee all the stakeholders an adequate access to infor-

mation in terms of quantity, quality and completeness

regarding the governing bodies, the management pro-

cess and results, the allocation of tasks, the budgeting

of the use of financial resources, to verify the achieve-

ment of goals and the accountability of each decision

or result. A system of accountability is important not

only to explain what has been done in the past, but it

is fundamental to identify the necessary changes and

corrective action to plan the future activities of LAG.

4 AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSYS ON

PUGLIA REGION LAGS

GOVERNANCE

The analysis produced in the following paragraph can

be considered as the result of a pilot study on the gov-

ernance of the LAGs operating in Puglia (Italy). The

reasons that led us to choose Puglia’s LAGs are essen-

tially two: 1) Puglia is the Italian region that has the

highest number of partnerships of this type. In fact,

there are 25 and they are evenly distributed through-

out the region. The number of LAGs in Puglia is

by far the highest compared to other regions and, in

percentage terms, they represent 12.76% of the to-

tal of Italian LAGs (no. 196); 2) Puglia, more than

any other region in Italy, has devoted a considerable

amount of community resources – nearly 300 million

euro – to a wide assortment of interventions and ben-

eficiaries with the aim to facilitate the process of en-

dogenous developmentthat will make the economy of

the rural areas more dynamic and productive.

4.1 Methodology Approach

Our aim is to evaluate the LAG’s governancein Puglia

region. This problem may be red as a multiattribute

decision making problem (MADM) In fact it is the

aggregation of several macroindicators as structure,

decision making processes and principles that ensure

a clear and transparent activity thus creating signifi-

cant value for the community. As every MADM prob-

lem there are three main frameworks in which we

may work: the multiattribute value theory (MAVT),

outranking approaches and interactive methods. We

present a method of the first type and in particular

a decision support system. The advantage of this

proposal is its visibility, the comparability of differ-

ent scenarios, the explicit choices of decision makers

and an easy way to rank different scenarios. Usually

its aspect is a decision tree that is built in a “bottom

up” procedure. The higher point is the output. Then

we have a first level of description by several macro-

indicators that experts have identified and so on till

the last leaves of the tree that are the initial inputs. In

this case we start in a different way as we have at our

disposal the replays of a survey submitted to members

of several LAGs in Puglia by a group of researcher of

University of Salento. In this situation the initial in-

puts are offered by the questions present in the survey.

The further aggregationsare obtained by the necessity

to give a meaning to the aggregate variables (see Ta-

ble 1). The instrument we propose is a Fuzzy Expert

System (FES) (Bandemer and Gottwald, 1995; Bo-

jadziev and Bojadziev, 2007; Kasabov, 1996; Piegat,

2001; Siler and Buckley, 2005; Castillo and Alvarez,

2007; Leondes, 1998; Pedrycz and Gomide, 2007).

FES models are cognitive models that, replicating the

human way of learning and thinking, allow to for-

malize qualitative concepts. It uses blocks of rules to

translate the experts judgments that, usually, are made

by numerical weights. The experts in charge of cod-

ifying the model’s operating rules make choices that

are visible and manifest in each step for the construc-

tion of the model. It contains an inferential engine

to reach a final evaluation. We have proposed this

instrument as we have not sufficient data to use data

mining methods, while we have experts of the gover-

nance sector disposable to help our work. The survey

questionnaires are given in a linguistic way and the

use of fuzzy logic has seemed the more fitting.

4.2 Construction of the System

The implementation of the fuzzy expert system in this

case has been divided into nine stages (Von Altrock,

1996):

1) Analysis of available data

2) Initial interview with experts to define the inputs

and factors for their aggregation

3) Construction of the decision tree

4) Subsequent talks to define the range and the

blocks of rules

5) Technical choices: aggregators and defuzzifying

6) Selecting complete data from the survey replies

and first output

7) Comparison with reference cases and calibration

8) Calculating new output: if there is no validation of

the result by the experts it returns to the previous

step

9) Analysis of the output.

LEADER EU Program and Its Governance - A Fuzzy Assessment Model

125

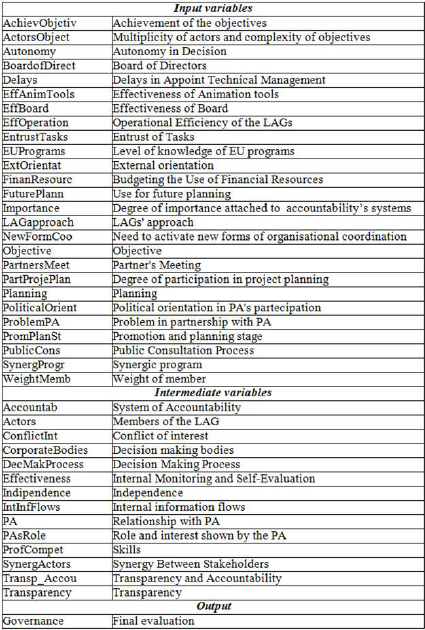

Figure 1: Input’s database.

Aggregating the 26 selected inputs in the corre-

sponding variables (see Figure 1), the model assumes

the configuration of a tree: the 26 inputs find aggre-

gation in 14 intermediate outputs which in turn are

the inputs of further aggregates up to the final output.

This output is the evaluation of the governance of the

LAGs, expressed as a ranking of the LAGs and ana-

lyzed according to the factors Actors, Decision mak-

ing process and Transparency. These in turn are the

results of the subsequent factors.

The construction of the model is then modular.

The evaluation is developed in successive steps (anal-

ogous to the decision-making process of individuals)

along the branches of the tree until you get to the

trunk: the input variables through intermediate out-

put variables leads to the final output of the model.

Figure 2 translates in a detailed way Table 1 using

the software fuzzyTECH (Von Altrock, 1996). The

experts that have contribute to build the system have

found the system result coherent with their previous

opinion. No other data are available and so we have

not had the possibility to test the system more times.

4.3 FES Mathematical Structure

In a fuzzy rule based system, the experts represent

their knowledge by defining the rules to describe the

characteristics of the risk assessment for each factor.

The input variables are processed by these rules to

generate an appropriate output. A fuzzy rule-based

system can be formalized as follows.

Suppose we have p inputs x

1

,... , x

p

and one output

y, with x

i

∈ X

i

and y ∈ Y. The fuzzy representation

of input variable x

i

is performed by associating to it

a number k(i) of linguistic labels, that is k(i) fuzzy

sets, we say A

1

i

,... , A

k(i)

i

, defined by the membership

functions µ

A

j

i

: X

i

→ [0,1] for j = 1, . . . ,k(i). Simi-

larly, the output variable y is described by k(y) fuzzy

sets B

1

,... , B

k(y)

defined by the membership func-

tions µ

B

j

: Y → [0, 1], with j = 1,...,k(y). The rule-

block is characterized by M rules where the m-th rule,

with m = 1, . . . , M, has the form

R

m

: IF x

1

is A

1m

and . . . and x

p

is A

pm

THEN y is B

m

.

Here the fuzzy set A

im

∈ {A

1

i

,... , A

k(i)

i

} is the linguis-

tic label associated with i-th antecedent in the m-th

rule and B

m

∈ {B

1

,... , B

k(y)

} is the linguistic label as-

sociated with the output variable in the m-th rule. We

assume that Mamdani implications (MIN) are used,

the fuzzy intersection operation (AND) corresponds

to the PROD operator, the fuzzy union (OR) corre-

sponds to the MAX operator, all rules which have

the same term in the rule conclusion are aggregated

using the BOUNDED SUM. Using the technique of

activation degree, given the crisp input values x

′

=

(x

′

1

,... , x

′

p

) ∈ X

1

×···×X

p

, for each rule m = 1,...,M

we compute the firing level (or degree of activation)

γ

m

(x

′

) as

γ

m

(x

′

) =

∏

i=1,...,p

µ

A

im

(x

′

i

).

For each j = 1, . . . , k(y) we consider the set M

j

⊂

{1, . . . , M} of all rules which have the term B

j

in the

rule conclusion. Thus {1, . . . , M} = M

1

∪ ··· ∪ M

k(y)

and M

j

∩ M

ℓ

=

/

0 for j 6= ℓ. We define γ

j

= γ

j

(x

′

) as

the BOUNDED SUM (or Łukasiewicz t-conorm) of

all rules which have the term B

j

in the rule conclu-

sion, that is

γ

j

= min{1,

∑

m∈M

j

γ

m

(x

′

)}.

Then we define B

j

∗

by

µ

B

j

∗

(y) = min

γ

j

,µ

B

j

(y)

, y ∈ Y.

The final output B

∗

is obtained as B

∗

=

S

k(y)

j=1

B

j

∗

, that

is

µ

B

∗

(y) = max

j=1,...k(y)

µ

B

j

∗

(y), y ∈ Y.

FCTA 2015 - 7th International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

126

Table 1: The factors for the evaluation of governance - Output of the Model.

3rd level factors 2nd level factors 1st level factors Output

Corporate bodies

Actors

Governance of

LAGs

Relationships with

Public Administration

Role and interest

shown by Public

Administration

Professional competences

Synergy between Stakeholders

Decision makingConflicts of interests

Independence

Internal Monitoring and Self Evaluation

TransparencyInternal information flows

Transparency and accountability

Accountability’s system

Figure 2: Layout.

To translate the fuzzy output into a crisp value, we

employ as defuzzification method the Center of Max-

imum (CoM).

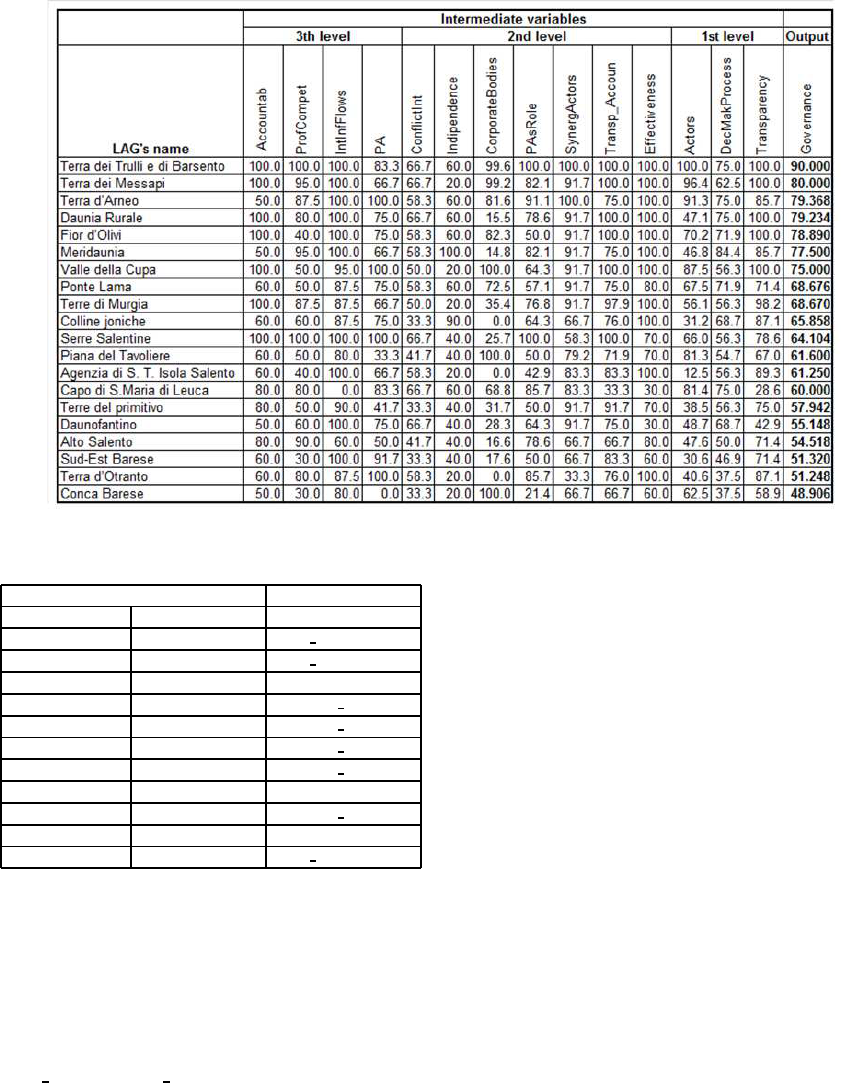

4.4 Variables and Blocks Of Rules

We now present the description of an input variable

and a rule block present in the previous layout. The

variable we choose as example is “PartnersMeet”, i.e.

% of private actors within the Assembly, shown in

Figure 3. Its granulation is made by four terms, “in-

sufficient”, “low”, “medium”, “high”, that translate

the experts opinions. Even the ranges of the four gran-

ules is fixed by experts.

Figure 3: Membership functions of “PartnersMeet”.

Following LEADER aim that requires a high per-

centage of private enterprise either in “PartnersMeet”

or in “BoardofDirect”, we have built the rule-block

in which “PartnersMeet” and “BoardofDirect” enter

LEADER EU Program and Its Governance - A Fuzzy Assessment Model

127

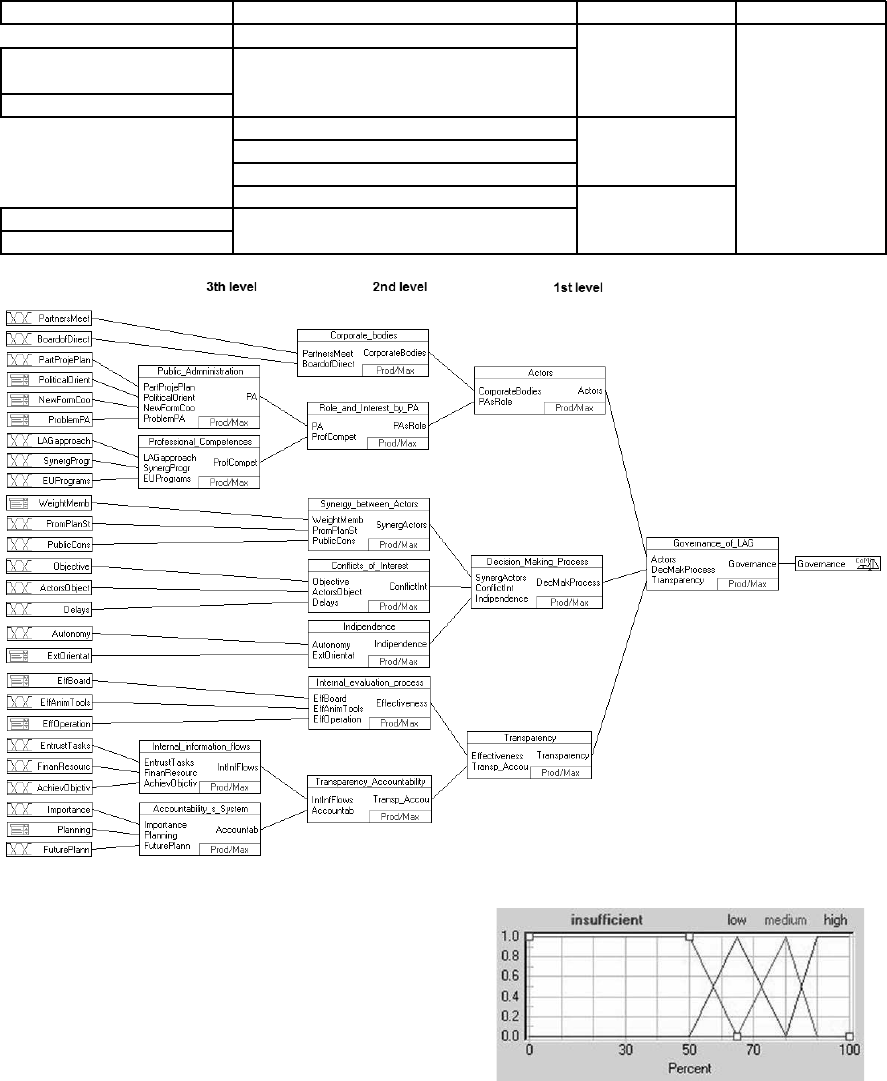

Figure 4: Governance’s quality ranking of the LAGs.

Table 2: Rules of the Rule Block “Corporate bodies”.

IF THEN

PartnersMeet BoardofDirect CorporateBodies

insufficient very low

insufficient very low

low low low

low medium medium low

low high medium high

medium low medium low

medium medium medium high

medium high high

high low medium high

high medium high

high high very high

producing an evaluation about the “CorporateBodies”

reliability. In fact we may observe that the first rule

says that if the percentage of private enterprise is “in-

sufficient” whatever the assessment of “BoardofDi-

rect” is, the evaluation about “CorporateBodies” is

very low. Similarly happens for the second rule. The

linguistic attributes of the “CorporateBodies” are de-

scribed by six terms in an increasing way, from the

“very low” till “very high”.

5 RESULTS

This paper applies fuzzy logic tools to creating a gov-

ernance rating for the different LAGs present in a re-

gion. This ranking is present in the ”output” column

of the table shown in Figure 4 in which the interme-

diate values divided in three levels are also showed.

The usefulness of this method is demonstrated by the

ease by which it highlights the formation of the out-

put and by the way in which it allows to identify, very

quickly, the critical issues and strengths that charac-

terize the governance of the single LAG. In this way,

the LAGs will not only be benefited from knowing

the rate of their governance, but they can implement

a program for increasing variable where the rating is

low.

For example, although two LAGs - Terra d’Arneo

e Daunia Rirale - have the same level of output rel-

ative to the intermediate variable ”decision-making

process” (DecMakProcess), a less detailed reporting

of the LAG (Terra d’Arneo) was more than offset

by the best composition of the shareholding structure

(CorporateBodies: 81.6 vs 15.5) and by the interest

shown by the PA in the LAG’s activities (PAsRole:

91.1 vs. 78.6). These values help to raise the level

of the variable ”Actors” (91.3 vs. 47.1) and allow to

place the LAG “Daunia Rurale” in the fourth position

preceded by the LAG “Terra d’Arneo”. This means

that “Daunia Rurale” has to improve its shareholding

structure, and that Public Entities must cooperate with

more interest in the decision making process of the

LAG.

FCTA 2015 - 7th International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

128

6 CONCLUSION

To date, there is still no framework for the assessment

of local governance, and the priority is to endorse a

combination of normative principles that will guide

it. Governance concerns the structures, processes,

rules and traditions through which decision-making

power that determines actions is exercised, and so ac-

countability is manifested and accomplished. Due

to partnerships’ dynamic, changing and evolution-

ary nature, governance of the LAGs evolves over the

partnership’s lifecycle. For this reason it is neces-

sary to be sensitive to the diversity of existing part-

nerships and to their changing, dynamic nature, es-

pecially when developing appropriate processes and

mechanisms. A framework is proposed for the as-

sessment of the governance of such partnerships even

if effective governance evaluation is a difficult goal

to achieve. This occurs because there are many key

aspects that have to be considered: composition of

the LAG’s bodies, participation of the different enti-

ties, the decision-making process, legitimacy, trans-

parency, accountability, ...For this reason, the frame-

work identifies a relatively small number of dimen-

sions (First Level Key Aspects) within which compo-

nents (Second Level Key Aspects) can work together

in a positive interactive way which leads to good re-

sults. The results from this survey suggest a few ar-

eas where policy makers and researchers can improve

on. The following are some recommendations to con-

sider:

(i) the framework offers a conceptual map by which

to examine the various dimensions, components

and element of good governance. It is important

to pay attention to the elements within the de-

cision making process and, in particular, to the

shared motivation for joint action that can stimu-

late a shared perspectiveof the strategic directions

to take;

(ii) the model shows that good governance is based

on the reliability of the LAG’s decision-making

processes that can stem from the synergies among

different members that adhere to the partnership

although they have different interests;

(iii) transparency and accountability are considered

important though many LAGs have not imple-

mented a valid system to acquire information to

understand not only what has been done in the

past. These activities are fundamental in identi-

fying the necessary changes and corrective action

needed to plan the future of the LAGs.

All these informations are obtained even thanks to the

instrument we propose. The effectiveness of the FES

lies in some aspects like the multiattribute, multidis-

ciplinary and fuzzy aspects of the problem. As we

have said, structured ways to evaluate the governance

of these EU projects at local level are not present.

This may be one starting point to due LAG institution

of a common way to be evaluated. This evaluation,

we think, should be necessary even in the direction to

supply other resources, in the future, using the merit

as decision making criteria.

REFERENCES

Addabbo, T., Facchinetti, G., Mastroleo, G., and Lang,

T. (2009). Evaluating firms’ gender equity by fuzzy

logic. In IFSA/EUSFLAT Conf., pages 1276–1281.

Addabbo, T., Facchinetti, G., Mastroleo, G., and Solinas,

G. (2007). A fuzzy way to measure quality of work

in a multidimensional perspective. In Advances in

Information Processing and Protection, pages 13–23.

Springer.

Anzilli, L., Facchinetti, G., and Mastroleo, G. (2013). “Be-

yond GDP”: A fuzzy way to measure the country well-

being. In IFSA World Congress and NAFIPS Annual

Meeting (IFSA/NAFIPS), 2013 Joint, pages 556–560.

IEEE.

Bache, I. (2007). Europeanization and multilevel gover-

nance: cohesion policy in the European Union and

Britain. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Bandemer, H. and Gottwald, S. (1995). Fuzzy sets, fuzzy

logic, fuzzy methods. Wiley Chichester.

Batory, A. and Cartwright, A. (2011). Re-visiting the

partnership principle in cohesion policy: The role of

civil society organizations in structural funds moni-

toring*. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies,

49(4):697–717.

Bojadziev, G. and Bojadziev, M. (2007). Fuzzy logic for

business, finance, and management. World Scientific

Publishing Co., Inc.

Brinkerhoff, D. W. and Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2011). Public–

private partnerships: perspectives on purposes, pub-

licness, and good governance. Public Administration

and Development, 31(1):2–14.

Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2007). Partnerships, governance and

sustainable development: Reflections on theory and

practice. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Castillo, E. and Alvarez, E. (2007). Expert Systems: Uncer-

tainty and Learning. Computational Mechanics pub-

lication. Computational Mechanics.

Commission, E. (2012). The partnership principle in the

implementation of the Common Strategic Framework

Funds - elements for a European Code of Conduct on

Partnership. SWD (2012) 106 final Commission Staff

Working Document, Brussels.

Emerson, K., Nabatchi, T., and Balogh, S. (2012). An inte-

grative framework for collaborative governance. Jour-

nal of Public Administration Research and Theory,

22(1):1–29.

LEADER EU Program and Its Governance - A Fuzzy Assessment Model

129

Forte, F., Mantovani, M., Facchinetti, G., and Mastroleo,

G. (2003). A fuzzy expert system for auction reserve

prices. In Artificial intelligence and security in com-

puting systems, pages 13–21. Springer.

Jacoby, W., Hall, P., Levy, J., and Meunier, S. (2014). The

Politics of Representation in the Global Age. Cam-

bridge University Press.

Jones, O. (2000). Rural challenge (s): partnership and new

rural governance. Journal of Rural Studies: Special

Issue on Growing Old in Rural Places, 16(2):171–

183.

Kasabov, N. K. (1996). Foundations of neural networks,

fuzzy systems, and knowledge engineering. Marcel

Alencar.

Kersbergen, K. v. and Waarden, F. v. (2004). governanceas

a bridge between disciplines: Cross-disciplinary in-

spiration regarding shifts in governance and problems

of governability, accountability and legitimacy. Euro-

pean journal of political research, 43(2):143–171.

Koppell, J. G. (2010). World rule: Accountability, legiti-

macy, and the design of global governance. University

of Chicago Press.

Lalla, M., Facchinetti, G., and Mastroleo, G. (2005). Or-

dinal scales and fuzzy set systems to measure agree-

ment: An application to the evaluation of teaching ac-

tivity. Quality and Quantity, 38(5):577–601.

Lalla, M., Facchinetti, G., and Mastroleo, G. (2008). Vague-

ness evaluation of the crisp output in a fuzzy inference

system. Fuzzy Sets and Systems, 159(24):3297–3312.

Leondes, C. (1998). Neural Network Systems, Techniques,

and Applications: Fuzzy logic and expert systems ap-

plications. Neural Network Systems, Techniques, and

Applications. Academic Press.

Lowndes, V. and Skelcher, C. (1998). The dynamics

of multi-organizational partnerships: an analysis of

changing modes of governance. Public administra-

tion, 76(2):313–333.

Magni, C., Mastroleo, G., and Facchinetti, G. (2001). A

fuzzy expert system for solving real option decision

processes. FUZZY ECONOMIC REVIEW, 6:51–73.

Magni, C. A., Mastroleo, G., Vignola, M., and Facchinetti,

G. (2004). Strategic options and expert systems: a

fruitful marriage. Soft Computing, 8(3):179–192.

OECD (2013). Rural-Urban Partnerships An Integrated

Approach to Economic Development. OECD Publi-

cations, Paris.

Pedrycz, W. and Gomide, F. (2007). Fuzzy Systems Engi-

neering: Toward Human-Centric Computing. Wiley.

Piegat, A. (2001). Fuzzy modeling and control, volume 69.

Springer Science & Business Media.

Shaoul, J., Stafford, A., and Stapleton, P. (2012). Ac-

countability and corporate governance of public pri-

vate partnerships. Critical Perspectives on Account-

ing, 23(3):213–229.

Siler, W. and Buckley, J. (2005). Fuzzy Expert Systems and

Fuzzy Reasoning: Theory and Applications. John Wi-

ley & Sons, Chichester, West Sussex.

Stephenson, P. (2013). Twenty years of multi-level gover-

nance:where does it come from? what is it? where

is it going?. Journal of European public policy,

20(6):817–837.

Tafuro, A. (2013). Gruppi di Azione Locale (GAL), gov-

ernance e sviluppo del territorio: analisi teorica ed

evidenze empiriche. Cacucci Editore Sas.

Von Altrock, C. (1996). Fuzzy logic and neurofuzzy appli-

cations in business and finance. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Westholm, E., Moseley, M. J., and Stenlas, N. (1999). Lo-

cal partnerships and rural development in Europe:

A literature review of practice and theory. Dalarnas

Forskningsrad.

FCTA 2015 - 7th International Conference on Fuzzy Computation Theory and Applications

130