MOOCs inside Universities

An Analysis of MOOC Discourse as Represented in HE Magazines

Steve White, Manuel Leon and Su White

Web Science Centre for Doctoral Training, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton, U.K.

Keywords: MOOCs, Content Analysis, University Stakeholders, HE Magazines.

Abstract: Digital news media discourse on MOOCs has been pervasive in educational publications over recent years,

and has often focused on debates over the disruptive potential of MOOCs at one extreme, and their survival

at the other. Whether such articles reflect the concerns of academics and other internal university

stakeholders is difficult to ascertain. This paper aims to determine the main concerns of internal university

stakeholders in terms of their MOOC development and implementation work, and whether these concerns

are reflected in the mainstream educational media. The study combines data from 2 previous studies (a

content analysis of MOOC literature, and a grounded theory case study of internal university stakeholders)

to establish key themes of concern for those working on MOOCs in Higher Education. An analysis of these

themes in 3 educational media publications is then conducted for the year 2014. The findings indicate a

clear focus in education media and among university stakeholders on new teaching practices and working

dynamics in Higher Education as a result of involvement in MOOC development work. We argue that for

many working on MOOCs in Higher Education, the debate about the future of MOOCs is over, and that

more practical concerns of appropriate implementation and effective working practices are of greater

importance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Discourse on Massive Open Online Courses

(MOOCs) has permeated digital news media,

especially in Higher Education publications (Bulfin,

Pangrazio, & Selwyn, 2014). Although some events

may reflect a decline in the interest of news media in

MOOCs (Kolowich, 2014a) since Pappano’s famous

announcement of the “Year of the MOOC” (2012),

there seems to be a sustained feed of MOOC stories

in all sorts of written media. This is especially so in

digital media, as suggested by Downes’ (2014)

tracking of MOOC mentions since 2012.

In many Higher Education Institutions, discussions

of MOOCs are no longer confined to educational

technology departments. Instead, these

conversations have spread to faculties at all levels.

Beyond the debates over their disruptive potential on

one extreme, and their survival on the other

(Hollands & Thirthali, 2014; Kolowich, 2013),

MOOCs are often the topic of everyday

conversations in many universities, since they are no

longer a subject of speculation and prediction, but a

matter of present practice.

MOOCs have effects not only on the learners who

take them, but also on the highly varied teams of

university staff involved in their creation and

delivery. As soon as the governance body of a

university makes the decision to go ahead with a

MOOC project, a number of concerns and

conversations arise within the institution. An action

plan is designed, often in the absence of protocols

and previous experience. The allocation of budgets,

roles, and responsibilities becomes a task which is

new to most members of the MOOC team.

Universities often share experiences of these

processes in interim reports (Edinburgh, 2013;

Ithaka, 2013; London, 2013), explaining the

organisational challenges and implications

encountered when embarking on MOOC

development and delivery. These implications for

institutions are also explained in a number of white

papers (Voss, 2013; Yuan and Powell, 2013),

containing sets of recommendations for faculty

boards and other decision making bodies.

This study aims to inform both practitioners and

decision makers about the main current concerns in

universities regarding MOOCs. The intention is to

provide an account of these concerns in terms of

109

White S., Leon M. and White S..

MOOCs inside Universities - An Analysis of MOOC Discourse as Represented in HE Magazines.

DOI: 10.5220/0005453201090115

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2015), pages 109-115

ISBN: 978-989-758-108-3

Copyright

c

2015 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

what motivates universities to attempt to incorporate

MOOCs into their educational offerings, and how

this motivation is changing or evolving as

understandings of MOOCs change, and as the

courses themselves evolve. It will also attempt

to determine the main perceived implications of

embarking on such an endeavour, and what aspects

of MOOC implementation are most discussed both

in the media and in HEIs.

2 RELATED WORK

Much meta research exists which reviews different

aspects of the state-of-the-art of MOOCs by

systematic analyses of the publications on MOOCs,

both academic and non-academic. Perhaps one of

the most cited is Liyanagunawardena et al. (2013),

which classifies and categorizes 45 peer-reviewed

studies on MOOCs, and identifies important

research gaps such as assessment and intercultural

communication issues. Further to this study,

Mohamed et al. (2014) ran a template analysis on a

broader set of papers, identifying assessment and

accreditation as key issues. BIS (2013) included

journalistic articles, academic papers and blogs to

explore perspectives on the impact of MOOCs on

both institutions and learners, identifying a high

degree of both enthusiasm and skepticism. Other

studies focus on more popular sources, such as

Bulfin et al. (2014), which analyzed news media

discourse related to MOOCs to examine the

acceptance of this form of education among

professional communities and a more general

audience.

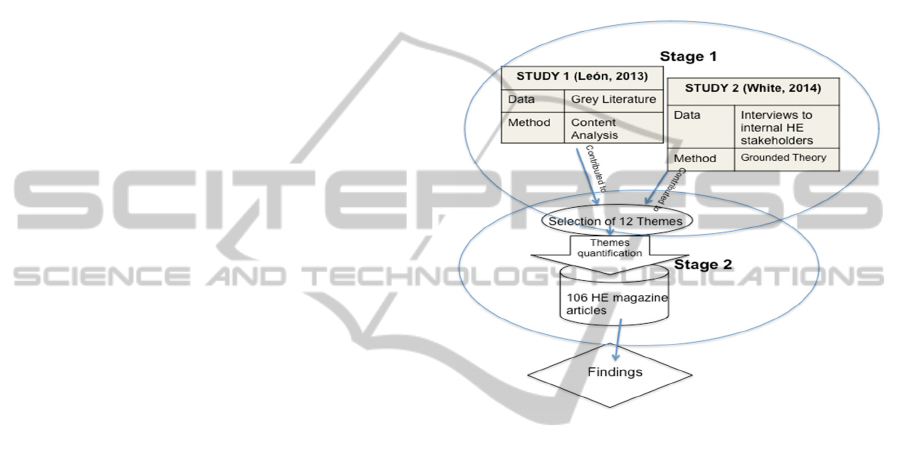

The current study drew on commonalities in the

findings of a content analysis of grey literature on

MOOCs (León, 2013) and a grounded theory study

of internal HE stakeholders involved in MOOC

development (White, 2014) to establish a set of 12

themes related to MOOC development in HE. A

keyword search of a corpus of educational media

articles published in 2014 was then conducted, and

the search results analysed for their relevance to

these themes. This study focuses on Higher

Education Institutions, showing primarily their

perspective. As such, the perspectives of learners, or

other stakeholders such as platform providers

(Coursera, Futurelearn, EdX) are outside the scope

of this study.

3 METHODOLOGY

This study was carried out in two stages, as shown in

Figure 1 below. The first stage involved an

examination of two independent studies in which a

convergence was identified. This convergence

consisted of a set of themes that fed the second

stage. The second stage involved a quantified

examination of the occurrences of these themes in a

corpus of specialist HE magazine articles in 2014.

Figure 1: Stages of the methodology

3.1 Desk Study, Content Analysis

In summer 2013, a desk study was carried out in

order to identify current debates on MOOCs at that

time (León, 2013). By then, there was already a

broad body of literature, both grey and academic

peer-reviewed that contributed to a polarised debate

between enthusiasts and skeptics (BIS, 2013). The

main search strategy used for this study consisted of

following reputed learning technologists in a social

site called Scoop.it, and gathering their curations. In

this way, all sources had already passed at least one

filter of relevance and rigour. Those identified by

Daniel (2012) as being written with an intention of

promoting MOOCs for profit rather than offering

objective accounts of their pedagogical potential

were disregarded.

Once the sources were gathered, they were analysed

with a method inspired by Krippendorf´s (2012)

Content Analysis, and Herring´s (2010)

recommendations for carrying out content analysis

on literature published online. The themes identified

in the project were MOOC quality, sustainability,

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

110

and impact, and debates were explored in a corpus

of 60 articles in total.

3.2 Interviews, Grounded Theory

The interview-based study used grounded theory

analysis of interview data to explore motivations

behind MOOC creation and implementation at the

University of Southampton from the perspective of

internal (university staff) stakeholders in the

development process (White, 2014). The university

currently runs 8 MOOCs and has been a member of

the FutureLearn consortium, a profit making MOOC

venture with a current membership of 40 institutions

(FutureLearn, 2014), since its launch in September

2013. In the study, 12 individuals were interviewed

as representatives of four main internal stakeholder

groups: management, content specialists (lecturers),

learning designers, and course facilitators and

librarians. A two-stage process for stakeholder

identification (following Chapleo and Sims, 2010)

was used.

In the absence of formal institutional policy on the

specific aims of MOOC development, stakeholders

were interviewed in order to reveal their perceptions

of the aims of the university in developing MOOCs,

and the stakeholders’ own aims in participating in

the development process.

3.3 Theme Selection

Similarities and differences exist in the aims,

procedures and applications of grounded theory and

qualitative content analysis. However, as recognised

in Cho and Lee (2014), commonalities exist in terms

of coding and categorising data, and identification of

underlying themes. Examination of the desk study

and grounded theory interview data at this level of

analysis revealed 12 common themes relevant to

institutional motivations in MOOC development and

the implications of these developments:

• MOOCs as impact on teaching practice: A

frequently cited idea was that the development

and implementation of MOOCs will have some

influence on the way teaching is conducted in

HEIs (whether online or face-to-face).

• MOOCs as HEI’s social mission: Different

HEIs (and the media which comment on them)

perceive a range of ways in which an

institution can fulfil its social mission, for

example by disseminating knowledge,

supporting learning, or fostering research.

• MOOCs as institutional strategy for keeping up

with HE evolution: Perceptions of institutional

motivations for MOOC development were

varied, but were often seen as simply a way for

institutions to keep pace with broader

developments in higher education.

• MOOCs as the avant-garde of new online

education provision: Some observers of

MOOCs perceive them as an opportunity to

experiment and be creative in higher education,

rather than as a more instrumental means to

some strategic goal.

• MOOCs as learner data providers: The

interviews and articles touched on the potential

value produced by various kinds of learner data

represented in MOOCs.

• Learning analytics inform learning design:

This theme focuses on a more specific use of

learner data than the above. The potential for

leveraging learning analytics was cited as a

motivation in the development and use of

MOOCs.

• New relationships between departments, new

work dynamics: A wide range of changes in the

way individuals, departments, and institutions

act and interact as a result of MOOC

development were cited in the literature review

and interviews.

• MOOCs as new business models: This concern

was widely cited in interviews and the

literature, although limited levels of consensus

or certainty emerged.

• MOOCs as means to engage with large

numbers of learners: HEIs are attempting to

grapple with the challenges of massive learner

numbers and learn from the experience.

Although massiveness has regularly been cited

as an obvious attraction in terms of business

models, it was also seen as an important and

distinctive feature of MOOCs in more general

educational terms.

• MOOCs as marketing: The potential of

MOOCs to act as marketing tools was cited in

the previous studies as a key institutional driver

for MOOC development, and linked to the

general sense of ‘hype’ surrounding them.

• MOOCs and accreditation: Mention was made

in the literature and interviews of the options

for and challenges of providing accreditation

for MOOCs, and the uncertainty that exists in

this area.

• MOOCs and completion rates: Completion

rates for MOOCs were a concern that arose in

the previous studies, though opinion varied on

the importance of completion rates for this kind

MOOCsinsideUniversities-AnAnalysisofMOOCDiscourseasRepresentedinHEMagazines

111

of course, and the comparability of MOOCs

and more traditional courses in this respect.

3.4 The Sample

The study focused on articles from 3 mainstream

educational media publications which have high

visibility on the Web (rather than peer-reviewed

journal articles). These media (Times Higher

Education, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and

Inside Higher Education) are widely seen as

“authoritative sources on higher education” (Bulfin

et al., 2014), and provide insight into the extent to

which concerns of HE professionals related to

MOOCs are reflected in mainstream media.

All magazine digital editions contained a search

engine, which facilitated the task of searching for the

keyword “MOOC” in each. Only articles which

included some substantive focus on the relevant

MOOC themes were included - those which

contained only passing references to MOOCs, or no

discussion of the selected themes were disregarded.

In total, a corpus of 106 articles from the three

magazines was analysed.

4 FINDINGS

Figure 2 depicts the frequency with which each

selected theme occurred in the corpus of articles.

The overwhelming majority of instances relate to

teaching practice (detected in 57 articles - more than

half of the sample). There were frequent discussions

of the perceived pedagogical benefits for institutions

when engaging in MOOCs. For example, Levander

(2014) reports how Rice University has developed a

portfolio of over 40 MOOCs motivated by what they

call assets, both in terms of materials and teaching

experience: building high quality content that can be

reused and repurposed, and providing valuable

experience of how to develop and deliver these

materials. Talbert (2014) also shares his experience

of screencasting for flipped classrooms as a novel

pedagogical approach in university lectures. Many

of the articles in which this theme was identified

report in one way or another how teachers are

adapting their teaching practices to cater for new

audiences, delivering through new communication

channels and platforms, and attempting to overcome

the different challenges that MOOCs pose to

educators.

Figure 2: Theme frequencies in article corpus.

The theme of MOOCs as catalysts of change in

relationships between departments and work

dynamics in universities was also frequently cited

(30 instances). Descriptions of developments in the

ways educational materials are collaboratively

produced within institutions were common, with

MOOC projects requiring cooperation between

teaching staff, educational technologists,

researchers, librarians, media producers, legal

advisors and others. Dulin Salisbury (2014), for

example, highlights the need for “team-based course

design”, whilst Straumsheim (2014a) reports on

work to involve local community stakeholders in

some aspects of course design at the University of

Wisconsin.

Discussion of MOOC business models was the third

most frequent theme in the sample literature (in 19

articles). Articles included discussion of more

flexible and open MOOC provider platforms

(Straumsheim, 2014c), possible approaches to the

use of advertising in MOOCs (Kim, 2014c) and

more critical views of the commercial imperatives

behind MOOCs and their impact on higher

education (Straumsheim, 2014d). The fourth most

frequent theme concerned the role of MOOCs as a

field for experimentation and innovation in online

education. A number of articles (n=11) explored

opportunities for creativity in education via MOOCs.

Parr (2014a) for example describes efforts by the

Open University to focus on social elements of

MOOC course development, and also to explores the

possibility for creating “nanodegrees” involving

very short courses on specific subjects.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

112

The theme of MOOCs and accreditation was

mentioned in 9 articles, and was addressed in a

number of ways. Straumsheim (2014b) discussed the

potential flexibility in course offerings and

accreditation which MOOCs may afford, while Kim

(2014d) notes the possibility for competency based

assessment and credentialing.

Two related themes were mentioned in the same

number of articles: ‘MOOCs as learner data

provider’ and ‘Learning analytics informs learning

design’. These themes were mentioned in 6 articles

respectively, some in the same article (Eshleman,

2014; Kim, 2014b). Eshleman (2014) highlights the

value of qualitative learner data for use in a case

study of her own institution, whilst also recognising

the contribution which learning analytics can make

to track student activity online. Kim (2014a) argues

that blended and online learning can provide

valuable data for learning analytics studies into the

learning process, and that this is a far richer source

of data for education research than a simple focus on

pass rates or other similar learning outcomes.

Straumsheim (2014d), however, cautions against

reliance on an abundance of data produced in

MOOCs, as interpreting such raw data can be

difficult and time consuming.

The theme of MOOCs as marketing for HEIs was

also mentioned in 6 articles. Kolowich (2014b) notes

the possibility of raising the profile of Rice

University among pre-college students, while Tyson

(2014) speculates about the relationship between

international student recruitment for US institutions

and MOOCs.

5 DISCUSSION

Perhaps the most salient result of this study is the

prominence of mentions of the impact of MOOCs on

teaching practice in universities. Findings in similar

studies place the pedagogical dimension of MOOCs

in a lower position in terms of presence in analysed

corpora. For example, in the ranking of MOOC

issues in media by Bulfin et al. (2014), pedagogy

occupies sixth position, behind other issues such as

the Higher Education marketplace and the free and

open nature of MOOCs. The above study, however,

analysed a broader sample which included non-

specialist newspapers, and included articles from

2013. A reason for this shift in focus could be our

institutional perspective and focus on MOOC

phenomena: as mentioned in the introduction, this

project has been carried out in a university, it is

addressed at universities, and seeks to understand

what happens in universities. An alternative

interpretation could be that of a tendency towards

the end of a debate on the disruptive nature of

MOOCs.

Changes in departmental relationships and working

dynamics was also an important theme identified in

both the stage 1 studies and stage 2 corpus analysis

of articles from 2014. In the 2014 article corpus

analysed in stage 2 of this study, discussions of the

new relationships between departments and new

work dynamics of institutions involved in MOOC

development were identified as the second most

frequently occurring theme. This perception of

MOOCs as a dynamic for internal institutional

change was also identified as a significant concern

in interviews with university stakeholders in the

grounded theory study from stage 1 of this research.

This seems to reflect a recognition that undertaking

MOOC development projects influences the way

individuals, groups and departments interact and

collaborate on such ventures. The corpus of

educational media sources report quite widely on

these issues, elaborating on examples of

collaborative practice or the ways in which

individual or departmental interactions have changed

or need to change in future. For universities, these

changing work dynamics are perceived to be an

important implication of participation in MOOC

development, perhaps because of the relative novelty

of MOOC development processes and initiatives.

The focus on this issue in the educational media

perhaps reflects further emphasis on MOOCs as a

practical concern, rather than a more speculative

debate over their potential disruptiveness or survival

in HE in the short-term.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study has shown the main concerns of internal

university stakeholders regarding MOOCs as

reported in specialist media. It seems that recent

media articles show greater concern with what

universities might do with MOOCs than what

MOOCs will do to universities, as has been a

concern in the past. An active rather than passive

attitude has been identified among educators and

within universities more broadly, as if educators

have tired of speculating on what will happen to

Higher Education as an industry with the advent of

MOOCs, and decided to get their hands dirty by

experimenting with new pedagogical approaches.

MOOCsinsideUniversities-AnAnalysisofMOOCDiscourseasRepresentedinHEMagazines

113

2012 was described as the year of the MOOC

(Pappano, 2012). Other ed-tech commentators have

described 2013 as the year of the anti-MOOC

(Waters, 2013; Bates, 2013). From what has been

found in this study, 2014 could be described as the

year of MOOC pedagogy.

MOOCs are not only building new relationships

between learners and educators, but also between

different roles and departments at universities. This

paper has shown that the media is also reporting new

work dynamics as a consequence of the inclusion of

MOOCs in the educational offerings of universities.

MOOCs seem to require the creation of new teams

and roles that had not previously existed, while more

established roles are being altered at various levels

of the organisational hierarchy of universities.

Media articles on academic activity do not, of

course, necessarily portray accurately the realities of

academic practice. However, the convergence found

in this study between the views of internal university

stakeholders and broader opinion in the educational

media seems to suggest that developing MOOCs is

currently more strongly associated with educational

innovation than marketing, democratisation, or new

business models.

REFERENCES

Bates, T. (2013). Look back in anger? A review of online

learning in 2013. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1c9qvv0.

BIS (Department of Business, Innovation and Skills)

(2013). The maturing of the MOOC: literature review

of massive open online courses and other forms of

online distance learning. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1c9qvv0.

Bulfin, S., Pangrazio, L., & Selwyn, N. (2014). Making

“MOOCs”: The construction of a new digital higher

education within news media discourse. The

International Review of Research in Open and

Distance Learning. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1AYkD3r.

Chapleo C. & Sims, C. (2010) Stakeholder Analysis in

Higher Education. Perspectives. 14 (1) pp. 12-20.

Cho, J., & Lee, E. (2014). Reducing confusion about

grounded theory and qualitative content analysis:

similarities and differences. The Qualitative Report. 19

(64) pp.1-20.

Daniel, J. (2012). Making sense of MOOCs: Musings in a

maze of myth, paradox and possibility. Journal of

Interactive Media in Education, 3. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/19KGOzt.

Downes, S. (2014) Measuring MOOC Media. Retrieved

from http://bit.ly/1DGWvmc.

Dulin Salisbury (2014) Impacts of MOOCs on Higher

Education. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1nA2vYA.

Edinburgh, U. of. (2013). MOOCs @ Edinburgh 2013 –

Report # 1 (p. 42). Edinburgh. Retrieved from

http://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/6683.

Eshleman, K. (2014) Are MOOCs Working for Us? Inside

Higher Education. Retrieved from:

http://bit.ly/1BJXLq0.

FutureLearn (2014) About. Retrieved from.

https://www.futurelearn.com/about.

Herring, S. C. (2010). Web content analysis: Expanding

the paradigm. International handbook of Internet

research (pp. 233-249). Springer Netherlands.

Hollands, F. M., & Thirthali, D. (2014). MOOCs:

Expectations and Reality. Full Report. May 2014.

New York, New York, USA. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1sLBfoH.

Ithaka S+R. (2013). Interim Report: A Collaborative

Effort to Test MOOCs and Other Online Learning

Platforms on Campuses of the University System of

Maryland. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/17AB5up.

Kim, J. (2014a) 6 Big Takeaways from the edX Global

Forum. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1r1cxUX.

Kim, J. (2014b) Here Come the Data Scientists. Inside

Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/Vxh425.

Kim, J. (2014c) MOOCs and Bad Online Advertising.

Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1AsogfW.

Kim, J. (2014d) Saltatory. Inside Higher Education.

Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1LjJJuu.

Kolowich, S. (2013). The MOOC “Revolution” May Not

Be as Disruptive as Some Had Imagined. The

Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1vlHWTH.

Kolowich, S. (2014a). The Year Media Stopped Caring

About MOOCs. The Chronicle of Higher Educaction.

Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1jFIeeV.

Kolowich, S. (2014b). Competing MOOC Providers

Expand Into New Territory—and Each Other’s. The

Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1vP3gff.

Krippendorff, K. (2012). Content analysis: An

introduction to its methodology. Sage.

León, M. (2013) Reactions on the emergence of MOOCs

in Higher Education Reactions on the emergence of

MOOCs http://bit.ly/1ztBu9C. in Higher Education.

Liyanagunawardena, T. R., Adams, A. A., & Williams, S.

A. (2013). MOOCs: A systematic study of the

published literature 2008-2012. The International

Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning.

Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1vlI85o.

London, U. of. (2013). MOOC Report 2013. Retrieved

from http://bit.ly/1qaMvGY.

Levander, C. (2014). It´s All About Assets. Inside Higher

Education. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1nbGejR.

Mohamed, A., Amine, M., Schroeder, U., Wosnitza, M., &

Jakobs, H. (2014). MOOCs A Review of the State-of-

the-Art. In CSEDU (pp. 9–20).

Pappano, L. (2012). The Year of the MOOC. The New

York Times, 2(12), 2012.

CSEDU2015-7thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

114

Parr, C. (2014a) Making MOOCs social is the next

challenge. Times Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1xk6Vq8.

Straumsheim, C. (2014a) All Things In Modulation. Inside

Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1sFk9tJ.

Straumsheim (2014b) A Platform For All Purposes. Inside

Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1pN6OQK.

Straumsheim (2014c) Data, Data Everywhere. Inside

Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1z5xScV.

Straumsheim (2014d) Profit or Progress? Inside Higher

Education. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/187FshT.

Talbert, R. (2014) Making Screencasts. The Pedagogical

Framework. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1DGYmr6.

Tyson, C. (2014) From MOOC to Shining MOOC. Inside

Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1vlJ1uL.

Voss, B. D. (2013). Massive Open Online Courses

(MOOCs): A Primer for University and College Board

Members. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1EdSO8j.

Waters, A. (2013) Top Ed-Tech Trends of 2013: MOOCs

and Anti-MOOCs. Retrieved from

http://bit.ly/1jG6CgI.

White, S. (2014) Exploring stakeholder perspectives on

the development of MOOCs in higher education a case

study of the University of Southampton. (MSc

Dissertation) http://bit.ly/1FDNJaZ.

Yuan, L., & Powell, S. (2013). MOOCs and Open

Education: Implications for Higher Education. CETIS.

Bolton. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1AYlWzn.

MOOCsinsideUniversities-AnAnalysisofMOOCDiscourseasRepresentedinHEMagazines

115