Agile Enterprise Architecture Management

An Analysis on the Application of Agile Principles

Matheus Hauder

1

, Sascha Roth

1

, Christopher Schulz

2

and Florian Matthes

1

1

Software Engineering for Business Information Systems (SEBIS), Technical University Munich,

Boltzmannstraße 3, 85748 Garching, Germay

2

Syracom, Parkring 4, 85748 Garching, Germany

{matheus.hauder, roth, matthes}@tum.de, christopher.schulz@syracom.de

Keywords: Enterprise Architecture Management, Survey, Agile, Enterprise Architecture Framework.

Abstract: Enterprise Architecture (EA) management has proven to be an efficient instrument to align business and IT

from a holistic perspective. Many organizations have established a permanent EA management function

responsible for modeling, analyzing, and defining the current and future EA state as well as the roadmap.

Similar as in software development, EA management initiatives face challenges that delay results,

complicate the collaboration, and deteriorate the overall work quality. While in software development, agile

principles and values reflected in tangible methods like Scrum and Extreme Programming are increasingly

adopted by organizations, there is little known whether these practices have already made their way into EA

management. Based on three research questions, this paper sheds light on the status-quo of agile principles

applied to EA management. We present results of an online survey among 105 industry experts working for

more than 10 industry sectors across 22 different countries.

1 INTRODUCTION

Globalization, frequently altering market conditions,

and the pressing need to reduce operating costs force

organizations to carry out complex business

transformations at a regular interval. However,

performed without a holistic and explicit picture of

the organization, these transformations are likely to

fail (Ross et al., 2006). An Enterprise Architecture

(EA) serves as a common means to look at an entire

organization as a whole. It captures both, business

aspects (e.g., business processes, business objects)

and IT aspects (e.g., interfaces, networks, devices)

as well as their interrelations (Buschle et al., 2012).

Being applied by an increasing number of

enterprises, the corresponding discipline EA

management fosters the mutual alignment of

business and IT (Weill and Ross, 2009).

EA management deals with capturing, modeling,

analyzing, and defining the current, planned, and

future architecture in conjunction with the roadmap

leading from the as-is to the target state (The Open

Group, 2011). However, EA management faces

various challenges ranging for instance from the late

return on investment to the delayed valuation of the

disciplines by concerned stakeholders (cf. e.g.

(Hauder et al., 2013), (Lucke et al., 2010) and

(Lucke et al., 2012).

When looking on the domain of software

development, researchers likewise to practitioners

propose the adherence to so-called agile values

helping to address these types of challenges

(Schwaber, 2004). Key to these values are agile

principles like the avoidance of waste (Gloger,

2010), an early stakeholder involvement (Beck et al.,

2001), and gathering feedback at an ongoing basis

(Highsmith and Cockburn, 2001).

In many cases these principles are based on lean

production practices initially applied by the Japanese

car manufacturer Toyota (Deming, 2000), (Holweg,

2007). As of today, the benefits of agile principles to

software development are still discussed

controversially (Reifer et al., 2003).

Several similarities between software

development - centering rather on single systems -

and EA management - focusing on the holistic

management of systems of systems - can be drawn.

Both disciplines have to handle frequently changing

requirements while ensuring a close collaboration

among the multi-disciplinary stakeholders. Focusing

on the latter, researchers have already proposed to

apply agile practices known from the development

38

Hauder M., Roth S., Schulz C. and Matthes F.

Agile Enterprise Architecture ManagementAn Analysis on the Application of Agile Principles.

DOI: 10.5220/0005424100380046

In Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2014), pages 38-46

ISBN: 978-989-758-032-1

Copyright

c

2014 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

of softw

a

Give

n

initially

Matthes

aware

o

Progra

m

(FDD),

a

their d

a

standpoi

endeavo

r

apply th

e

agile p

r

today’s

Open G

r

Yet,

EA ma

n

ground

conclud

e

‘Whi

engi

n

desi

g

man

a

The res

illustrat

e

the rese

review

domains

online

s

manage

m

question

applicat

i

with the

organiz

a

The

findings

literatur

e

explain

softwar

e

EA ma

n

our rese

a

setup of

experts

i

in Secti

o

remarks

2 A

G

E

N

To iden

t

values i

n

approac

h

(Webste

r

a

re (Ambler,

2

n

that in m

a

promoted

and Schulz,

o

f agile pra

m

ming (XP),

a

nd might ap

p

a

y-to-day b

u

nt, we wi

t

r

s of our i

n

e

se agile pra

c

r

escriptions

a

EA manage

m

r

oup, 2011).

literature do

c

n

agement is

s

is

m

issing.

A

e

to the follo

w

ch agile prin

c

n

eering dom

a

g

n of an o

r

a

gement prac

t

earch ap

p

ro

a

e

d in Figure

1

arch questio

n

to identify

. Based on t

h

survey to

e

m

ent. In or

d

n

s and gain

a

i

on of the p

r

specific EA

a

tions (Haude

r

following se

c

we made w

h

e

looking for

how agile p

r

e

developme

n

n

agement. In

a

a

rch hypothe

s

f

an online su

r

i

n the field.

W

o

n 5 and 6 be

on futu

r

e res

e

G

ILE PRI

N

TERPRI

t

ify tangible

m

n

EA manag

e

h

as recomm

e

r

and Watso

n

2

010a), (Buc

k

a

ny cases E

A

through IT

2013), EA i

n

ctices, e.g.

Feature Dri

v

p

ly their acco

r

u

siness. Fro

m

t

ness that

E

n

dustry part

n

c

tices. In addi

a

re implicitl

y

m

ent frame

w

c

umenting th

s

carce; in pa

r

A

gainst this

w

ing research

o

c

iples known

f

a

in

s

hould b

e

r

ganization-

sp

t

ice?’

a

ch and the

1

: After defin

i

n

s, we cond

u

agile princi

p

h

ese principle

e

valuate thei

r

d

er to ans

w

a

deeper und

e

r

inciples, we

management

r

et al., 2013).

c

tion (Sectio

n

h

en perusing

agile pointer

s

r

inciples and

n

t world cou

l

a

ddition to t

h

s

es, Section 4

r

vey we con

d

W

e analyze an

fore concludi

n

e

arch.

NCIPLE

S

SE ARC

H

m

aterial on a

g

e

ment, we ap

p

e

nded by We

b

n

, 2002). Duri

n

k

l et al., 2011

)

A

manageme

n

(Hauder,

R

n

itiatives are

Scrum, Ext

r

v

en Develop

m

r

ding principl

e

m

an empi

r

E

A manage

m

n

ers increasi

n

t

ion, we diag

n

incorporate

d

w

orks, e.g.,

(

e agile natur

r

ticular empi

r

background,

o

bjective:

f

rom the soft

w

e

applied fo

r

p

ecific agile

deliverables

i

ng the scope

u

cted a liter

a

p

les from

o

s we designe

d

r

usage in

w

er the rese

e

rstanding o

n

correlated

t

challenges o

f

n

2) provide

s

EA manage

m

s

. In Section

3

values fro

m

d be adopte

d

h

e introductio

outlines the

m

d

ucted among

d

discuss the

n

g the paper

w

S

IN

H

ITECTU

R

g

ile principles

p

lied a struct

u

b

ster and W

a

n

g April 201

3

)

.

n

t is

R

oth,

well

r

eme

m

ent

e

s in

r

ical

m

ent

n

gly

n

ose

d

in

(

The

r

e of

r

ical

we

w

are

r

the

EA

are

and

a

ture

o

ther

d

an

EA

e

arch

n

the

t

hem

f

the

s

the

m

ent

3

we

m

the

d

by

o

n of

m

ain

105

data

with

R

E

and

u

red

a

tson

3

we

per

u

p

ro

Go

o

an

d

we

fol

l

ma

n

tra

n

so

u

me

t

fol

l

giv

e

b

e

b

foc

u

20

1

ma

n

p

ra

c

the

agi

l

an

20

0

fur

t

co

m

20

1

p

ra

c

qu

a

co

u

Or

a

fro

m

u

sed diffe

r

ceedings, an

d

o

gle Scholar,

d

the library

o

carried out

e

l

owing Englis

n

agement’ a

n

n

slations. Aft

e

u

rces (title,

a

t

hod of her

m

l

owing sourc

e

e

n their focus

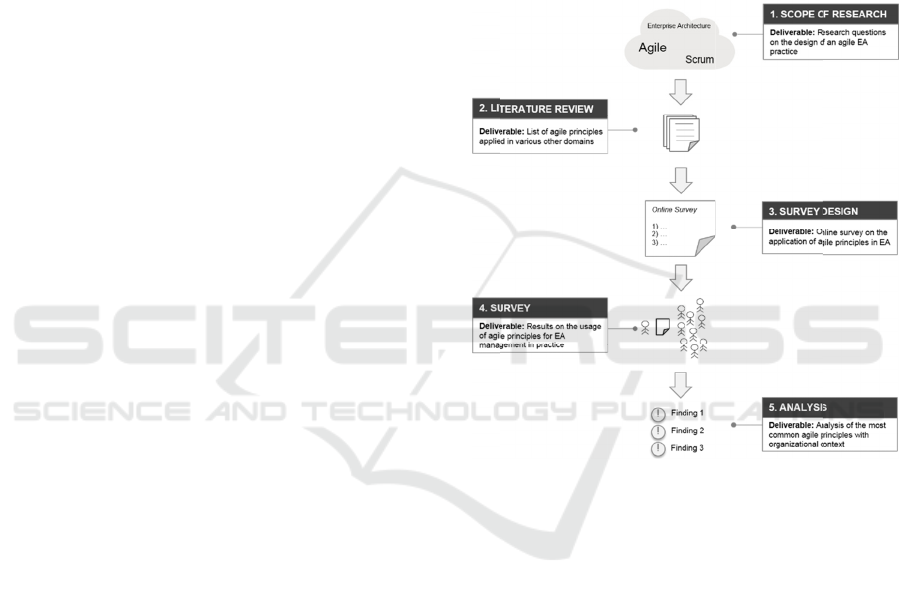

Figure 1: R

e

Ambler acce

n

b

usiness driv

u

sed on pro

d

1

0a). Based

o

n

agement i

s

c

titioner poi

n

managemen

t

l

e, among ot

h

iterative an

d

0

9). In the lat

e

t

her, proposi

n

m

plemented

b

1

0b). The fin

d

c

tical work

e

a

ntitative scal

e

Bob Rhubart

u

ld be turne

d

a

cle represent

a

m

architects,

r

ent IS j

d

books usin

g

IEEExplore,

C

o

f our researc

e

lectronic ful

h

keywords:

’

n

d ’agile’ as

e

r a first ana

l

a

bstract, outl

m

eneutic tex

t

e

s have been

on the topic.

e

search approa

c

n

tuates that

E

e

n, evolution

a

d

ucing valua

b

o

n an examin

a

s

typically

t

s out six pie

t

of enterpri

s

ers, simplicit

y

d

increment

a

e

st of his rep

o

n

g an agile

b

y several ke

y

ings publishe

d

e

xperience wi

t

e

.

describes ho

w

more agile

a

tive highligh

t

developers,

a

j

ournals, c

o

g

the Web o

f

Citeseer, Spr

i

c

h institution.

l

l-text search

e

’

enterprise ar

c

well as thei

r

l

ysis of the

o

l

ine) adherin

g

t

comprehen

identified a

s

c

h and delivera

b

E

A managem

e

ary, collabor

a

b

le artifacts

n

ation of pro

b

coping

w

e

ces of advic

e

se architectu

y

, focus on p

e

a

l approach

o

rts, Ambler

g

architectur

e

y

techniques

d by Ambler

a

i

th no evalua

t

w an EA ma

n

(Rhubart, 2

0

h

ts the necess

a

a

nd other sta

k

o

nference

f

Science,

i

ngerLink

Thereby,

e

s on the

c

hitecture

r

German

o

verall 53

g

to the

sion, the

s

relevant

b

les.

e

nt has to

a

tive, and

(Ambler,

b

lems EA

w

ith, the

e

to make

r

es more

e

ople, and

(Ambler,

g

oes even

e

process

(Ambler,

a

ll root in

t

ion on a

n

agement

0

10). The

a

ry buy-in

k

eholders

Agile Enterprise Architecture Management - An Analysis on the Application of Agile Principles

39

at all levels of the organization. Next to the

importance of conversation in particular with the

developing teams, the manager considers the

involvement of enterprise architects at the project

level as very crucial. Again, all suggestions are

based on in-the-field work based on a single

company (employee) perspective.

Friedrichsen and Schrewe see typical EA

management problems (e.g. losing sight of

fundamentals, becoming a slave of the EA

management framework) as a reason to introduce

agile values (Friedrichsen and Schrewe, 2010). The

consultants advise to launch an EA management

initiative with clear goals and a limited scope while

always keeping potential risks in mind. In their eyes,

frameworks and tools have to be considered as

toolboxes that ensure to reach the stated goals more

efficiently.

While Eric Landes recommends applying

concrete techniques like retrospectives and lessons

learned action items, iterative cycles, as well as

automated acceptance criteria in the emergent design

of an architecture (Landes, 2012), Scott Nelson

assumes two distinct viewpoints when discussing the

similarities and differences of managing enterprises

architectures vs. developing software in an agile

manner (Nelson, 2012).

As another industry expert and active blogger,

Gabhart advises to avoid big bang EA management

projects attempting to “boil the ocean”, thus are too

big in scope (Gabhart, 2013). Instead of that, the

author proposes to start off small, building up an EA

management capability in an incremental and

iterative 4-step process. Lastly, the staff member

Gattadahalli of the former IT Company EDS shares

the knowledge of an agile management of EAs in

terms of seven critical success factors (Gattadahalli,

2004).

After having introduced EA management to the

reader of their book, Bente, Bombach, and Langade

proposes six so-called building blocks helping to

render the discipline more agile and lean (Bente et

al., 2012). Benefiting from examined sources paired

with their professional experience, Bente et al.,

describe how to streamline the architecture

processes, setup an agile EA project, and foster

collaboration and participation. Even though their

explanations are backed by several fictitious

examples, no quantitative results are provided that

would prove the adoption of agile practices in EA

management.

To respond to the problems often encountered in

EA management, Shirazi et al. propose a framework

rendering the discipline more agile (Shirazi and

Rouhani, 2009). Named Agile Enterprise

Architecture Framework (AEAF), the artifact

consists of seven models and eleven interactions

both based on agile principles and values. Even if

the authors do not indicate any relations, the five

viewpoints and six project aspects also included in

AEAF resemble the Zachman framework (Zachman,

1987).

Although AEAF touches on several agile aspects

like regular feedback or focus on cooperation, the

research group’s paper neither proves the empirical

relevance of an agile EA management nor it validate

the framework work in practice.

Rooted in lean principles, information

technology architectures, and systems engineering

methods, Comm and Mathaisel propose the Lean

Enterprise Architecture (LEA), a three-phase

structure to organize the activities for the

transformation of the enterprise to agility (Comm

and Mathaisel, 2010). The researchers combine their

framework with concepts from the Lean Enterprise

Transformation Engineering while also

incorporating lean principles and practices in the

resulting process. However, their work does not

detail on these principles or explains how an agile

enterprise should evolve its EA.

As one of the most popular approaches, The

Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF) 9.1

does not explicitly recommend to manage an EA in

an agile style (The Open Group, 2011). In turn, a

more agile organization is considered as a surplus

brought along by a “good” enterprise architecture.

Notwithstanding, with concepts like iterations to

develop a comprehensive architecture landscape and

architecture, to manage changes to the

organization’s architecture capability, as well as

appropriate stakeholder management the EA

framework TOGAF promotes important agile

principles.

The striving for agile principles and values

enhancing the efficiency of EA management is

mainly found in practitioners’ circles. While only a

small number of experts emphasize the misfit of

both disciplines, e.g. (Nicholette, 2007), the majority

of industry authors consider agile means as being

well suited for EA management (Banerjee, 2011).

As of January 2014, few academic publications and

frameworks embrace or even mention to apply an

agile management means for EAs. Studied sources

are very new, indicating that the mind-set of an agile

EA management is still nascent. No contribution

was found that investigated on the current status quo

of agile practices in industry.

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

40

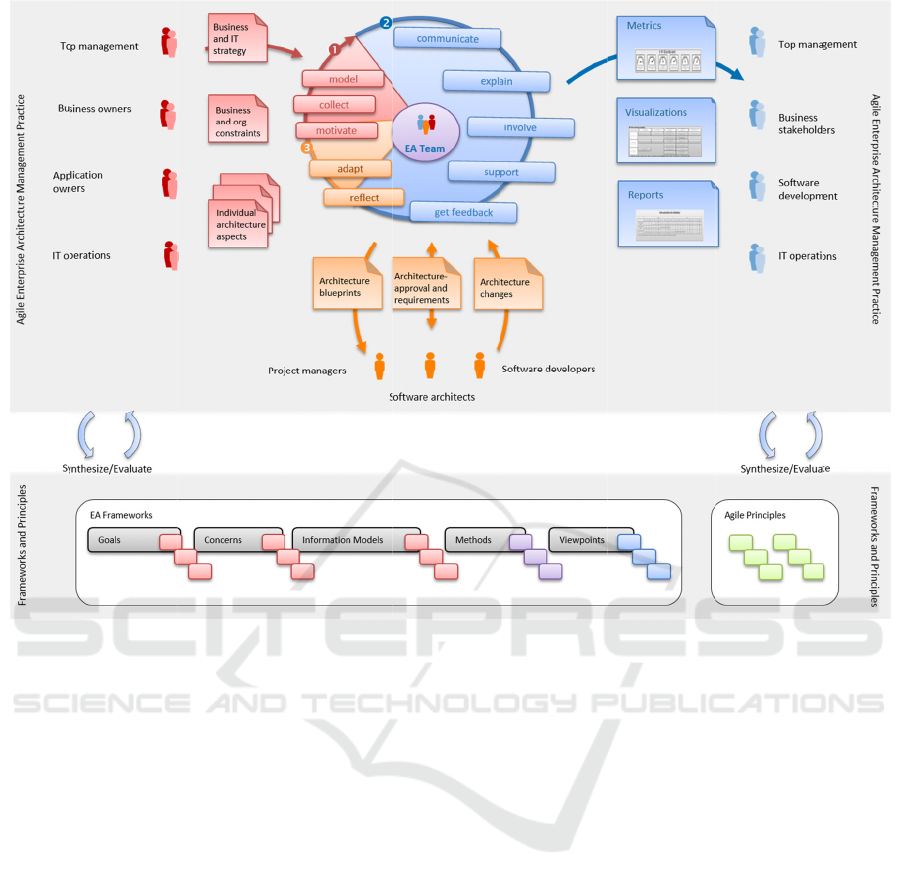

Figure 2:

current E

A

3 A

P

D

E

T

O

A

R

The ap

p

p

rincipl

e

p

art of

t

p

rincipl

e

evaluate

d

manage

m

the ap

p

manage

m

Whe

n

managi

n

early a

n

maintai

n

changin

g

2005).

T

enterpri

s

delivera

b

increme

n

Design of an

A

frameworks

w

P

PLYING

E

VELOP

M

O

ENTER

P

R

CHITE

C

p

lication of

e

s to EA is ill

u

t

he figure s

h

e

s that are

d

to design

m

ent function

p

lication of

m

ent.

n

focusing o

n

n

g EAs, the A

n

d constant

n

ing a respo

n

g

requiremen

t

T

ranslated int

o

s

e architects

b

les as ea

r

n

tal and iter

organization-s

p

w

hich are exte

n

AGILE S

M

ENT P

R

P

RISE

C

TURE

agile softw

u

strated in Fi

g

h

ows the fra

m

synthesized

an organiz

a

. In the follo

w

these pri

n

n

the workin

g

gile Manifest

delivery

o

n

sive attitude

t

s (Beck et

a

o

an EA ma

n

should stri

v

r

ly as poss

i

ative approa

c

p

ecific agile E

A

n

ded by agile p

r

OFT

W

A

R

R

INCIPL

E

a

re develop

m

g

ure 2. The l

o

m

ework and

a

and const

a

a

tion-specific

w

ing, we illus

t

n

ciples for

g

style applie

d

o

recommen

d

o

f results

w

with regar

d

a

l., 2001), (C

n

agement con

t

v

e to ship

t

i

ble, pursue

c

h, and em

b

A

managemen

t

rinciples, cf. (

R

R

E

E

S

m

ent

o

wer

a

gile

a

ntly

EA

trate

EA

d

for

d

s an

w

hile

d

s to

ohn,

n

text,

t

heir

an

b

race

ch

a

Si

m

EA

mo

s

ov

e

an

co

n

en

o

Sp

e

a

m

ex

p

20

1

20

1

the

onl

y

en

v

int

e

the

b

e

Ro

b

the

sh

o

t

practice base

d

R

oth et al., 201

4

a

nges regardi

n

m

ilar to their

s

management

s

t important

t

e

r completene

s

As goes the

A

EA manag

e

n

stant pace tr

y

o

ugh leeway

e

aking of fle

x

m

odus opera

n

p

eriment and

1

2). In confo

r

1

0) as well a

s

EA manage

m

y

upon st

a

v

ironment w

i

e

rference dur

i

other side o

f

eager to give

b

ertson, 200

6

EA manag

e

o

uld be incorp

o

d

on theoretica

l

4

).

n

g

t

heir wor

k

oftware deve

l

team should

a

t

asks first wi

t

s

s and quality

A

gile Manife

s

m

ent team

s

y

ing to avoid

for

r

eflectio

n

x

ibility, agile

n

di where m

e

try out ne

w

r

ming to the

p

s

the one-

p

ie

c

m

ent team sho

a

keholders’

i

th little or

n

g the work

f

the spectru

m

regular feed

b

6

) on the res

u

e

ment team.

o

rated into th

e

l

concepts ofte

n

k

ing style an

l

oping count

e

always take c

th a valuatio

n

y

(Stal, 2012).

s

to (Beck et

a

should adva

n

overtime wh

i

n

s and retro

s

literature rec

o

e

mbers are a

l

w

things (

C

p

ull-

p

rincipl

e

c

e flow (Fish

e

o

uld create de

l

demand w

i

no distrac

t

(Schwaber,

2

m

, stakehold

e

b

ack (Ross,

W

u

lts delivere

d

However,

t

e

work of the

n

found in

d

results.

e

rparts, an

are of the

n

of time

a

l., 2001),

n

ce in a

i

le having

s

pectives.

o

mmends

l

lowed to

C

oldewey,

e

(Gloger,

er

, 2000),

l

iverables

i

thin an

t

ion and

2

004). On

rs should

W

eill and

d

through

t

he latter

team.

Agile Enterprise Architecture Management - An Analysis on the Application of Agile Principles

41

In the sense of working software and simplicity

(Beck et al., 2001), (Highsmith and Cockburn,

2001), EA management results should be as usable,

simple, and accessible as possible for EA

management stakeholders. Benefiting from each

individual deliverable the EA management team

releases, stakeholders should be satisfied with the

outcome and value the EA management team

creates. As called for in agile literature (Highsmith,

2002), (Gloger, 2010), EA management results

should be of the highest quality, crafted in a way that

they only respond to the stakeholders’ demand with

a level of done that is understood and agreed upon.

Centering on the actors performing the work,

agile sources emphasize a cross-organizational team

whose members are specialized to perform various

tasks (Gloger, 2010) in a self-organized manner

(Beck et al., 2001). From an educational perspective

(Coldewey, 2012), the EA management team

members should have special skills and training in

multiple organizational areas (e.g., infrastructure,

processes, application) while being capable to

manage the sequence order their tasks are eventually

completed.

Both, high education and expertise permit the

team to speak the same language as stakeholders and

information providers on a daily basis. In line with

the fifth agile principles (Beck et al., 2001), the EA

management team leader has to create a positive

work environment while catering to the team’s self-

organization. Besides an intrinsic motivation (Beck

et al., 2001), and work satisfaction, each EA

management team member should have a notion of

his/her colleagues’ duties and results. Looking on

the overall organizational structure (Fisher, 2000),

EAM tasks should be accomplished through small

sub-teams in which roles and responsibilities are

clearly defined and understood. Finally, the team

requires strong diplomacy and negotiation skills

employed when interacting with stakeholders and

EA information providers.

4 RESEARCH QUESTIONS,

SURVEY DESIGN, AND

EMPRICAL BASIS

In above outlined literature the application of agile

principles for EA management has been widely

suggested by authors in the community. However, to

date neither a comprehensive list of practical applied

agile principles in EA management is published nor

an empirical validation thereof exists.

Since in many cases EA management is initially

promoted through IT (Hauder et al., 2013) which

adopts agile principles more or less eagerly, we

formulate the first research question as follows:

Research Question 1: What are frequently applied

agile principles for EA management in practice?

Our second research question aims at validating

observations, e.g. on the shift towards an

incremental and iterative work fashion for certain

EA management challenges. Not only this enhances

the scoping during the launch of EA initiatives,

incremental and iterative developed products might

provide stakeholders with early results and, thus,

lead to an increased buy-in.

Research Question 2: Which agile principles are

used in enterprises for certain EA management

challenges?

Typically EA management puts focus on a long term

plan how organization should evolve, while agile

practices promote the constant change of ongoing

projects. Since both approaches appear contradictory

at the first look, we formulate the third research

question as follows:

Research Question 3: What are challenges for the

design of an organization-specific agile EA

management practice?

To evaluate these three questions on an empirical

basis, we compiled an online questionnaire using 3-

point Likert scale questions. The contained questions

were based on the collection of agile principles we

explained above. To optimize the questionnaire’s

design, we conducted a pre-test with three

independent non-related researchers who were

requested to complete our survey.

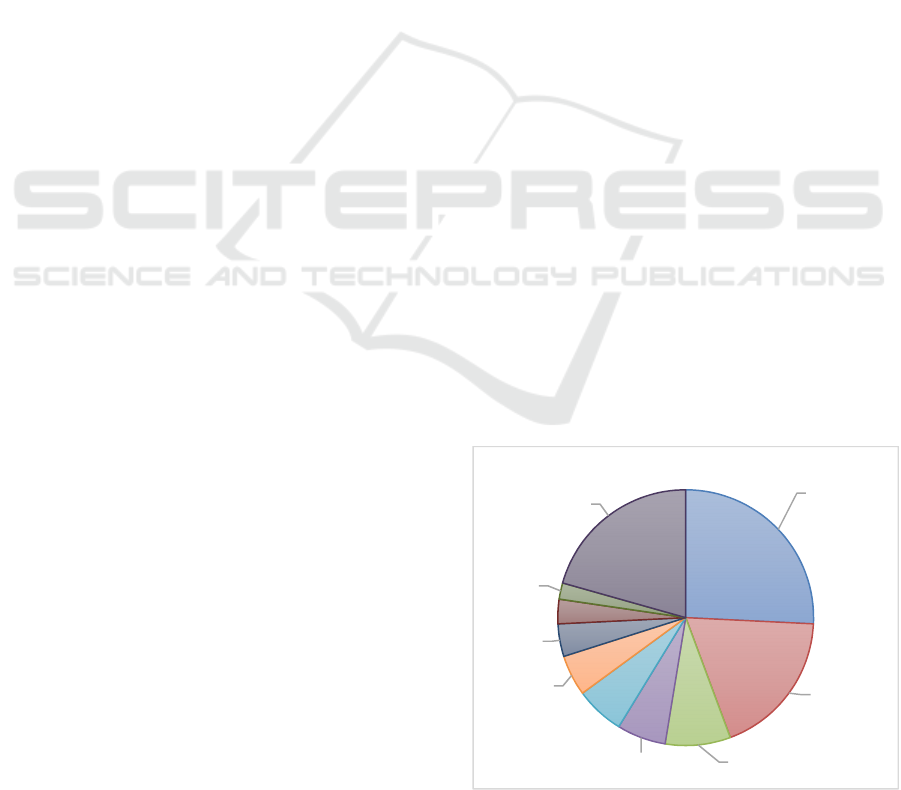

Figure 3: Industry sector of organizations (n and %).

IT Consulting 25

26%

Finance 18 19%

Public Service 8

8%

Manufacturing 6

6%

Telecommunicati

ons 6 6%

Education 5 5%

Management

consulting 4 4%

Transportation 3

3%

Health 2 2%

Other 20 21%

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

42

The final version of the questionnaire was

available for 21 days. To receive relevant

information we targeted participants working in EA

management or related fields. Using e-mail, we sent

over 1100 survey invitations to industry experts we

collaborated with during the last 8 years.

Figure 4: Job titles of participants (n and %).

In addition, the survey has been published in the

two online forums Xing and LinkedIn, announcing

them as topics related to EA or strategic IT

management. We received input from 178 survey

participants, filtered duplicate answers, and ended

up with 105 completed answers for the evaluation,

i.e. a dropout quote of ~41%.

As the survey was conducted primarily in

Germany, 61 (~58%) participants are employed in

Europe. 18 (~17%) work in the USA and 26 (~25%)

are employed in other countries having less than 10

responding participants. Figure 3 illustrates the

distribution of the industry sectors of the

participating organizations. IT consulting is the

largest sector, whereas all consultancies were

requested to answer on behalf of one particular EA

management engagement. IT consulting is followed

by the Finance and Public sectors.

Figure 4 depicts the participants of the online

survey divided by job title. The largest groups

consist of Enterprise Architects followed by IT

Architects and Consultants. Among the participants

are also Business Architects and members of the

management board. In average, questioned

organizations have an experience of 5 years in EA

management.

5 AGILE PRINCIPLES FOR

ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

MANAGEMENT IN PRACTICE

In the following three subsections the research

questions are evaluated based on our empirical data

set. The second research question is evaluated by

applying the Pearson’s chi-square test to validate the

dimensions in our data set.

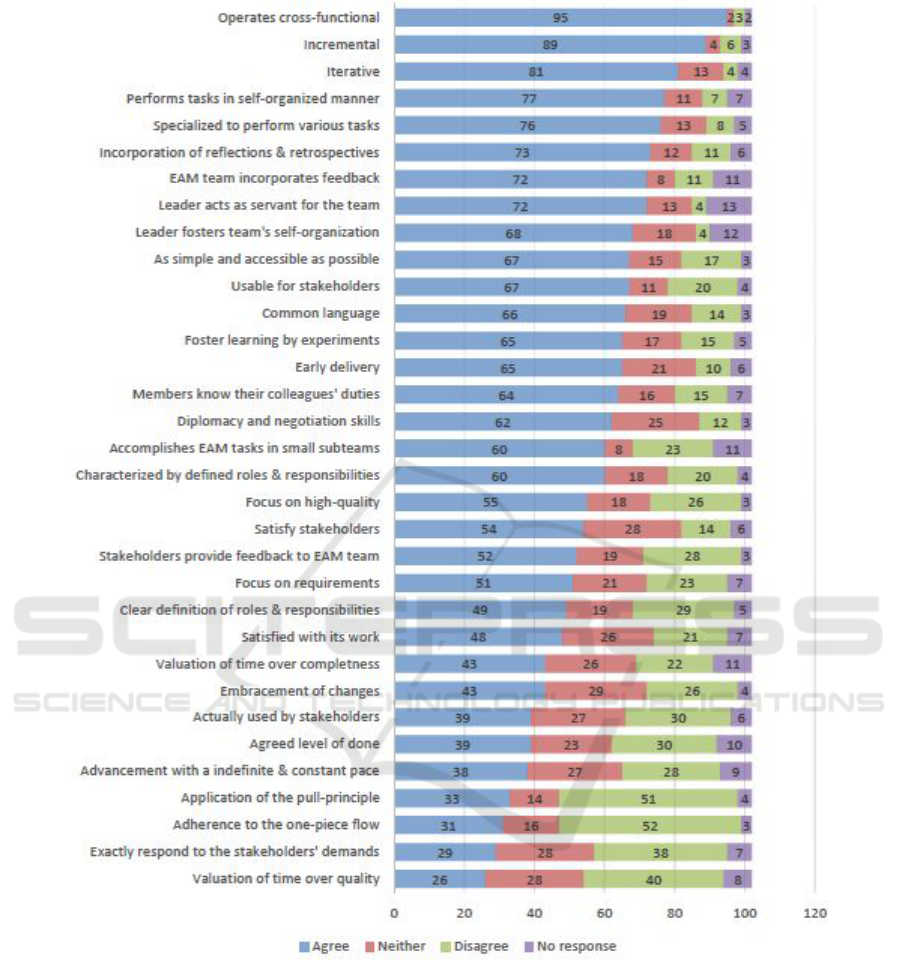

5.1 Application of Agile Principles

The first research question deals with the application

of agile principles for EA management in practice.

Figure 5 illustrates the practical adoption of agile

principles in EA management ordered by frequency.

As depicted, organizations adhere to agile principles

with a different degree of intensity, confirming our

assumption that the applicability of agile principles

varies for EA management. For instance, while most

organizations perform retrospectives within their EA

management team, only few value time over quality.

Most EA management initiatives apply an iterative

(~79%) and incremental (~87%) approach. About

93% of the organizations apply EA management in a

self-organized manner. Moreover, ~75% say that

they act cross-functionally.

While the overwhelming majority of

organizations apply several agile principles for the

introduction and operation of their EA management

initiatives in practice, some principles are less

frequently traceable. In particular some of these less

frequent agile principles are related with the quality

and completeness of the developed EA products.

Only ~42% of the participating organizations

apply time over completeness and only ~25% rate

time over quality for the developed EA products.

Next to agile principles related to quality and

completeness of the developed EA products, actual

stakeholder demands and utilization of the produced

EA products by these stakeholders are only applied

by the minority of the organizations in our dataset.

With ~38% only a small number organizations are

truly concerned whether these EA products are

actually used by stakeholders.

Enterprise

Architect 54 51%

IT Architect 15

14%

Consultant 12

11%

Business

Architect 6 6%

CxO 6 6%

IT Operations 3

3%

Software

Engineer 1 1%

Other 8 8%

Agile Enterprise Architecture Management - An Analysis on the Application of Agile Principles

43

Figure 5: Applied agile principles for EA management in practice (n=105).

5.2 Agile Principles and Enterprise

Architecture Challenges

We answer the second research question by

correlating EA management challenges from our

empirical basis (cf. Hauder et al., 2013) with the

agile principles illustrated in Figure 5. Due to space

limitations, we only illustrate the statistical

correlations for three major EA management

challenges with agile principles using Pearson’s chi-

square test.

The challenge late valuation of EA management

through stakeholders appears in ~51% of the

participating organizations. According to our

statistical test these organizations apply the principle

adherence to one-piece flow with p = .047 (p ≤ .05).

In addition, the principle focus on requirements

resulted in a goodness of fit test of p = .00004 (p ≤

.05). Further agile principles that correlate with this

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

44

challenge are advancement with an indefinite &

constant pace p = .002 (p ≤ .05), stakeholders

provide feedback to EA management team p = .0002

(p ≤ .05), agreed level of done p = .009 (p ≤ .05),

useable for stakeholders p = .042 (p ≤ .05), and as

simple and accessible as possible p = .005 (p ≤ .05).

All other agile principles were not statistically

dependent on this challenge for the given relevance.

Around ~38% of the organizations are struggling

with outdated EA results. This means that

architecture descriptions are often outdated before

they are complete and often understood as a project

rather than a continuous process. The agile

principles characterized by defined roles &

responsibilities correlates with p = .004 (p ≤ .05),

members knows their colleagues’ duties with p =

.0001 (p ≤ .05), focus on high quality p = .005 (p ≤

.05), satisfied with its work p = .001 (p ≤ .05),

adherence to one-piece flow p = .00001 (p ≤ .05),

incorporation of reflections & retrospectives p =

.001 (p ≤ .05), agreed level of done p = .0001 (p ≤

.05), and usable for stakeholders p = .001 (p ≤ .05).

Reluctant information providers are a challenge

for ~65% of the organizations. This is a very critical

problem since enterprise architects heavily rely on

the information and knowledge provided by

stakeholders. The agile principle satisfied with its

work correlates with p = .043 (p ≤ .05), focus on

requirements p = .00001 (p ≤ .05), application of the

pull principle p = .009 (p ≤ .05), embracement of

changes p = .030 (p ≤ .05), valuation of time over

quality p = .004 (p ≤ .05), as simple and accessible

as possible p = .00001 (p ≤ .05), and exactly respond

to stakeholders’ demand p = .003 (p ≤ .05) correlate

with this challenge.

5.3 Designing an Agile Enterprise

Architecture Management Practice

Designing an agile EA management practice is a

challenging issue. While EA management

frameworks typically work towards a long range

vision of the organization or a business case, agile

practices incorporate findings from ongoing projects

immediately in the process. To put it in another way,

both approaches appear contradictory due to their

top-down and planning (EA management)

respectively bottom-up and emergent course of

action.

Regarding the challenges EA management

initiatives in organizations are faced with neither of

these approaches can solve all challenges on his

own. Integrating both approaches within one agile

EA management practice that is tailored to the

specific demand of the organizational context would

be desirable. The findings presented in this paper

provide an initial empirical basis for further research

on an agile EA management practice. This

compromises the development of agile EA

management roles, activities, and deliverables.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we provided an empirical foundation

for agile principles applied to EA management by

today’s organizations. Due to the survey design, the

asked industry experts could only confirm or reject

the application of an agile principle for EA

management. Details about their actual

implementation are yet to be revealed. As of today,

this might be challenging, given the scarce literature

on agile EA management and only the implicit

adoption through EA frameworks. Regarding our

survey results, a potential bias might originate from

the lack of a common understanding on how to

operationalize agile principles in EA management.

Further research could examine the impact of

agile principles on the success and benefits of EA

management initiatives. Thereby, the efforts should

account for different organizational factors like the

size of the business, structure, EA management

experience, industry, and tool support. Further

studies could also focus on the correlation (and later

causalities) between challenges encountered in EA

management and possible mitigation through agile

principles.

REFERENCES

Ambler, S. W. (2009): Agile Enterprise Architecture.

http://www.agiledata.org/essays/enterpriseArchitecture

.html. Last opened: 27/08/2013.

Ambler, S. W. (2010a): Agile and Enterprise Architecture.

https://www.ibm.com/developerworks/mydeveloperw

orks/blogs/ambler/entry/agile_and_enterprise_architec

ture?lang=en. Last opened: 27/08/2013.

Ambler, S. W. (2010b): Agile Architecture: Strategies for

Scaling Agile Development. http://www.agile

modeling.com/essays/agileArchitecture.htm. Last

opened: 27/08/2013.

Banerjee, U. (2011): Agile development and Enterprise

Architecture practice - Can they coexist. Technology

Trend Analysis. http://setandbma.wordpress.com/

2011/04/11/agile-development-and-enterprise-

architecture-practice-can-they-coexist. Last opened:

27/08/2013.

Beck, K., Beedle, M., Bennekum, A. van, Cockburn, A.,

Agile Enterprise Architecture Management - An Analysis on the Application of Agile Principles

45

Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., Grenning, J., et al.

(2001): Manifesto for Agile Software Development.

Agile Alliance. http://agilemanifesto.org. Last opened:

27/08/2013.

Bente, S., Bombach, U., & Langade, S. (2012):

Collaborative Enterprise Architecture: Enriching EA

with Lean, Agile, and Enterprise 2.0 Practices. 1

st

ed.

Morgan Kaufmann, Burlington.

Buckl, S., Matthes, F., Monahov, I., Roth, S., Schulz, C.,

& Schweda, C. M. (2011): Towards an Agile Design

of the Enterprise Architecture Management Function.

6

th

International Workshop on Trends in Enterprise

Architecture Research (TEAR). Helsinki.

Buschle, M., Grunow, S., Matthes, F., Ekstedt, M.,

Hauder, M., & Roth, S. (2012): Automating enterprise

architecture documentation using an enterprise service

bus. In Proceedings of the 18

th

Americas Conference

on Information Systems. Washington.

Cohn M. (2005): Agile Estimating and Planning, Prentice

Hall PTR, Upper Saddle River.

Coldewey, J. 2012: Was heißt hier eigentlich “Agil”?

Kennzeichen agiler Organisationen. In

ObjektSpektrum 05/2012.

Comm, C. L., & Mathaisel, D. F. X. (2010): A Lean

Enterprise Architecture for Business Process Re-

engineering and Re-marketing. 12

th

International

Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (pp.

497–500). Madeira.

Deming, W. E. (2000): Out of the Crisis. MIT press,

Cambridge.

Fisher, K. (2000): Leading Self-Directing Work Teams.

McGraw-Hill, New York.

Friedrichsen, U., & Schrewe, I. (2010): Leichtgewichtige

Unternehmensarchitekturen – Wie Agilität bei der

Einführung eines EA Management helfen kann. In

OBJEKTspektrum, EAM/2010.

Gabhart, K. (2013): Generating Value through

Information Architecture. http://archvalue.com/agile-

enterprise-architecture (last opened: 27/08/2013)

Gattadahalli, S. (2004): Agile Enterprise Architecture

(AEA) - 7 Steps to Success. London.

Gloger, B. (2010): Scrum. In Informatik-Spektrum, 33(2):

195–200.

Hauder, M., Roth, S., Matthes, F., & Schulz, C. (2013):

Organizational factors influencing enterprise

architecture management challenges. 21

st

European

Conference on Information Systems (ECIS). Utrecht.

Highsmith J. (2002): Agile Software Development

Ecosystems. Pearson Education, Indianapolis.

Highsmith, J., & Cockburn, A. (2001): Agile software

development: the business of innovation. In Computer,

34(9): 120–127.

Holweg, Matthias (2007): The genealogy of lean

production. In Journal of Operations Management 25

(2): 420–437.

Landes, E. (2012): Agile Software Development Concepts

for Enterprise Architects. http://www.devx.com/

architect/Article/47842. Last opened: 27/08/2013.

Lucke, C., Krell, S., & Lechner, U. (2010): Critical Issues

in Enterprise Architecting - A Literature Review. In

AMCIS 2010 Proceedings (pp. 1-11). Association for

Information Systems.

Lucke, C., Bürger, M., Diefenbach, T., Freter, J., &

Lechner, U. (2012): Categories of Enterprise

Architecting Issues - An Empirical Investigation based

on Expert Interviews. In D. C. Mattfeld & S. Robra-

Bissantz (Eds.), Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik

(pp. 999-1010). GITO mbH Verlag, Berlin.

Nelson, S. (2012): Making Enterprise Architecture Work

in Agile Environments. http://www.devx.com/

architect/Article/47871. Last opened: 27/08/2013.

Nicholette, D. (2007): Enterprise Architecture and Agile.

Musings of a Software Development Manager.

http://edgibbs.com/2007/10/04/enterprise-architecture-

and-agile. Last opened: 27/08/2013.

Reifer, D. J., Maurer, F., & Erdogmus, H. (2003): Scaling

agile methods. Software, IEEE, 20(4): 12-14.

Roth, S., Zec, M. & Matthes, F. (2014): Enterprise

Architecture Visualization Tool Survey 2014.

Technical Report, Technische Universität München.

Ross, J. W., Weill, P., & Robertson, D. (2006): Enterprise

architecture as strategy: Creating a foundation for

business execution. Harvard Business Press, Boston.

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002): Analyzing the Past to

Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review.

MIS Quarterly, 26(2): 13–23.

Weill, P., & Ross, J. W. (2009): IT Savvy: What top

executives must know to go from pain to gain. Harvard

Business Press, Boston.

Rhubart, B. (2010): Agile Enterprise Architecture. Oracle

Magazine. http://www.oracle.com/technetwork/issue-

archive/2010/10-nov/o60architect-175580.html. Last

opened: 27/08/2013.

Schwaber, K. (2004): Agile Project Management with

Scrum. 1

st

ed., Microsoft Press, Redmond,

Washington.

Shirazi, H. M., Rouhani, B. D., & Shirazi, M. M. (2009):

A Framework for Agile Enterprise Architecture. In

International Journal of Intelligent Information

Technology Application, 2(4): 182–186.

Stal, M. (2012): Softwarearchitektur und Agilität - Freund

oder Feind?. OOP 2012. München.

The Open Group (2011): TOGAF® Version 9.1, Van

Haren Publishing, Zaltbommel.

Zachman, J. A. (1987): A framework for information

systems architecture. In IBM systems journal, 26(3):

276-292.

Fourth International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

46