Use of Mobile Collaborative Tools for the Assessment of

Out-of-Classroom Courses in Higher Education

Cloud Technologies Applied to the Monitoring of the Practicum

Xavier Perramon

1

, Josepa Alemany

2

and Laura Panad

`

es

3

1

Dept. of Information and Communic. Technologies, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Roc Boronat 138,

08018 Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

2

Dept. of Economics and Business, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Ramon Trias Fargas 25–27,

08005 Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

3

Faculty of Law, University of Cambridge, 10 West Road, Cambridge CB3 9DZ, Cambridge, U.K.

Keywords:

Out-of-classroom Learning, Practicum, Monitoring, Collaborative Software, Mobile Apps, Cloud Computing.

Abstract:

In this paper we propose the use of collaborative tools to enhance traditional e-learning platforms for university

courses that are developed outside the school environment, as is the case of a Practicum or internship in a

company or external institution. These courses have specific requirements with regard to monitoring, guidance

and assessment of students, and we postulate that collaborative tools, usually implemented as cloud-based

applications, combined with mobile technologies, today affordable to most students, constitute a suitable

platform for implementing the assessment of this type of courses.

1 INTRODUCTION

Out-of-classroom learning plays an important role

in education as a complement to formal learning at

school. The philosophy of education known as con-

structivism (Kolb, 1984) describes how new knowl-

edge based on real life experience is constructed and

integrated into existing knowledge.

But out-of-classroom learning activities have spe-

cial requirements with regard to student monitoring

and guidance, due to the environment where this

learning takes place, often far from the physical pres-

ence of the instructor. Today, technological solutions

exist that facilitate online guidance and assessment of

activities outside the classroom.

As part of a more general study aimed at facili-

tating graduates’ college-to-work transition and seek-

ing to improve labour insertion in the context of the

European Higher Education Area (EHEA), in a previ-

ous work (Perramon et al., 2012) we have developed

a monitoring system for university students taking a

Practicum course, i. e. an internship or external prac-

tice stage in a company or institution, integrated into

the Moodle e-learning platform. The learning activity

in this case is not a single task that makes part of a

broader subject, but usually a whole course in itself.

Our focus in this paper is on generalising the sys-

tem to any type of out-of-classroom course, and on

extending it to make use of mobile devices (phones,

tablets) which are nowadays more and more ubiqui-

tous among the population, and in particular among

university students. A widely deployed technology

that is suitable to our needs is collaborative software,

usually implemented today as cloud-based applica-

tions.

2 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

The main objective of this work is to study the us-

ability of mobile technologies for the monitoring and

assessment of out-of-classroom educational activities,

with an especial attention to the Practicum.

To achieve this goal, we firstly study the character-

istics of out-of-classroom learning in general, and the

specific requirements for the Practicum where three

different actors are involved: the student, the work-

place tutor, and the academic tutor.

Next, we consider the currently available tools

for performing the monitoring of these activities in

a collaborative way. We focus on those which pro-

vide ubiquitous access by means of mobile technolo-

gies. We then analyse how to integrate these tools into

239

Perramon X., Alemany J. and Panadès L..

Use of Mobile Collaborative Tools for the Assessment of Out-of-Classroom Courses in Higher Education - Cloud Technologies Applied to the Monitoring

of the Practicum.

DOI: 10.5220/0004962102390244

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 239-244

ISBN: 978-989-758-022-2

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

the learning management systems that provide sup-

port for the assessment of the students’ activities, and

specifically the Practicum in our case. Finally, we dis-

cuss some advantages and disadvantages of the use of

these technologies and we draw some conclusions.

The initial hypothesis of this study is that the com-

bination of collaborative tools and mobile technolo-

gies provide an appropriate framework for the devel-

opment of the monitoring system that satisfies the re-

quirements of the Practicum and of out-of-classroom

education in general. This appropriateness can be

confirmed if the advantages of mobile collaborative

systems overcome any possible disadvantages.

The methodology of this work is based on the

analysis of the different tools and their capabilities in

order to assess their usability for our purposes. The

outcome is a proposal of the work to be developed

for implementing the monitoring of the Practicum

through mobile collaborative tools.

3 OUT-OF-CLASSROOM

LEARNING

In general, “education outside the classroom” usually

refers to any school learning that does not take place

in a class of students with a teacher (Neill, 2008).

In our case, we focus on courses in higher education

that are developed completely out of the campus en-

vironment. Examples of this type of learning activi-

ties include research projects, fieldwork and, specifi-

cally, the Practicum in university degrees. In the con-

text of the work presented here, we understand by

Practicum a course intended to make students put in

practise the theory they have learnt, to be developed

typically as an internship in the professional environ-

ment of a welcoming institution, i. e. a company, a

public administration, or any other kind of organisa-

tion. The benefits of the Practicum in the learning pro-

cess have been described in different models (Jaques

et al., 1993), and in particular in Kolb’s (1984) “expe-

riential learning”, in line with the constructivist the-

ory.

Several aspects of the Practicum make it singular.

For the purpose of our work the interesting point is

that, unlike classical courses where a teacher interacts

with a group of students (one-to-many interaction),

in the Practicum there is usually a triangular interac-

tion between three actors: the student, the academic

tutor or teacher, and the external tutor or person in

the company or external institution who is in charge

of the student during his or her internship. Each of

the three actors interacts individually with the other

two: the student with both tutors for consultation and

guidance (each tutor in their respective scope, either

the university or the workplace), and the tutors with

each other for the assessment and monitoring of the

student’s work. In turn, each of the vertices of this

triangle can be manifold: the internship may be taken

by a team of two or more students working in col-

laboration, the academic supervision may be carried

out collegiately by a tutor responsible for all intern-

ships in a degree and a tutor directly in charge of the

student, and there may be several supervisors at the

workplace, typically a senior and a junior supervisor,

the latter providing more day-to-day guidance to the

student’s activities. Our proposal focuses on collabo-

rative tools for student monitoring, but we could also

introduce in this proposal a module for collaborative

evaluation (Rodr

´

ıguez-Campos, 2012).

Out-of-class activities can take place in very di-

verse environments, such as an office, a workshop, or

maybe even in the open air. This raises the need for

proper monitoring and student guidance, suitable to

the context where the activity is developed. Given the

peculiarity of the triangular relationship between par-

ticipants, we consider collaborative tools accessible

from mobile devices an appropriate solution for the

monitoring of the Practicum.

In its simplest form, the interaction between the

three actors can be regarded as an instance of co-

operative editing of a document. Such a document,

once finalised, could be the student’s final report of

their activity during the internship, to be submitted

for approval in order to assess their achievements in

the Practicum course. But during its preparation, this

document can be a container for the periodic progress

reports that the student has to elaborate, for the stu-

dent’s enquiries to the tutors asking for advice and

the corresponding responses, for the interactions be-

tween both tutors regarding their observations on the

student’s progress, etc. Most collaborative tools pro-

vide some form of cooperative editing of documents

that can be used in this way, but some of them also in-

corporate more advanced functionalities to facilitate

this type of interactions.

4 COLLABORATIVE TOOLS

4.1 Basic Characteristics

Collaborative software, also called groupware, pro-

vides the foundations for computer-supported cooper-

ative work or CSCW (Carstensen and Schmidt, 1999).

These tools facilitate the cooperation among several

users to fulfil a given task, by means of a common

information space. This space can be used to share

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

240

documents, messages, etc. in order to achieve the

joint goals. In addition to this, project management

tools or projectware, which form a subset of collab-

orative software, cope with task interdependencies in

order to coordinate the various activities making up

the project.

Different architectural models have been used for

implementing collaborative software. The two main

models are the classical client-server architecture,

where each user runs a specific client application to

access the collaborative space, and the web-based ar-

chitecture, where the role of the client is played by a

general-purpose web browser. This latter model has

evolved to the cloud paradigm, whereby all the nec-

essary resources, including applications and data, re-

side in a network of virtual servers (National Institute

of Standards and Technology, 2011), and is rapidly

becoming more and more widespread.

One of the most popular collaborative tools today

is Google Apps (Google Inc., nd), based on cloud

technology, and encompassing applications like joint

editing of documents, presentations and spreadsheets,

polls and surveys, forums, virtual meetings, hangouts,

etc. Google Drive is the specific application within

Google Apps to manage the storage and sharing of

such resources. Another collaborative tool is Zoho

(Zoho Corp., 2013), an office suite that comprises

a number of components, grouped into business ap-

plications, productivity applications, and collabora-

tion applications. The latter include Zoho Chat, Zoho

Docs, Zoho Projects, etc. The Yammer service (Yam-

mer Inc., 2014) is another example of a tool that can

be used in a corporative environment for communi-

cation between its members. It is usually cited as an

“enterprise social network”, but it can be used in sce-

narios other than businesses. More recently, Asana

(Asana, nd) has been developed as a teamwork tool

for managing conversations and tasks in a more flex-

ible way than simple e-mail exchange. As of today,

there are dozens of different collaborative tools avail-

able, and their characteristics have been compared in

many studies, e. g. Reixa et al. (2012), Dr

˘

aghici et al.

(2013), etc.

Like many others, Google Apps, Zoho and Asana

are online services following the “software as a ser-

vice” (SaaS) model. In these systems, all data (doc-

uments, calendars, conversations, etc.) and the appli-

cation itself do not reside in the user’s computer or

device but in the server or servers supplied by the

service provider, i. e. in “the cloud”. The case of

Yammer, although the server-side application is more

characteristic of a social network, can also be in-

cluded in this category.

The four examples of collaborative tools men-

tioned above are available for free, under certain con-

ditions for personal projects or small groups, or for a

monthly or yearly fee for larger professional teams.

More commercial solutions also exist, but at present

we focus on tools with basic functionality that can be

used at no charge in an academic institution. An ex-

ample of a commercial tool is Trunity (Trunity Hold-

ings Inc., 2013).

4.2 Mobile Access

The ability to access the collaborative tools from a

mobile device, i. e. a smartphone or tablet, is a pos-

itive factor for out-of-classroom courses given their

externality.

Usually web-based applications can be accessed

with most available web browsers, including those

which are incorporated into mobile devices, i. e.

smartphones and tablets. However the peculiarities

of these devices (smaller display, touch-based input

system) can complicate the user experience if the ap-

plication is not specifically designed for them. Most

applications intended to be used in mobile devices are

therefore designed as mobile applications or “mobile

apps” (or simply “apps”).

This is the case for many of the collaborative tools

described in the previous subsection. In particular,

Google Drive as well as Asana and Zoho provide a

mobile app version that can be downloaded to the

user’s device before accessing the corresponding tool.

This of course requires the user to be provided

with such a mobile device, either a smartphone or a

tablet. However today it is more and more common

for students to have their own personal mobile de-

vice that they can use for training purposes at school.

Actually, some academic institutions are introducing

a BYOD policy (Bring Your Own Device) in their

learning systems, a process that is not free from con-

troversy, but it is out of the scope of this paper to de-

bate this issue.

5 INTEGRATION WITH

LEARNING MANAGEMENT

SYSTEMS

External tools have been successfully integrated into

learning management systems (LMS) using different

methods, e. g. through the IMS Basic Learning Tools

Interoperability (BLTI) standard (IMS Global Learn-

ing Consortium, 2010). If a LMS and an external tool

both implement the BLTI interface, the tool can be in-

tegrated so that it is seen by users as though it was a

UseofMobileCollaborativeToolsfortheAssessmentofOut-of-ClassroomCoursesinHigherEducation-Cloud

TechnologiesAppliedtotheMonitoringofthePracticum

241

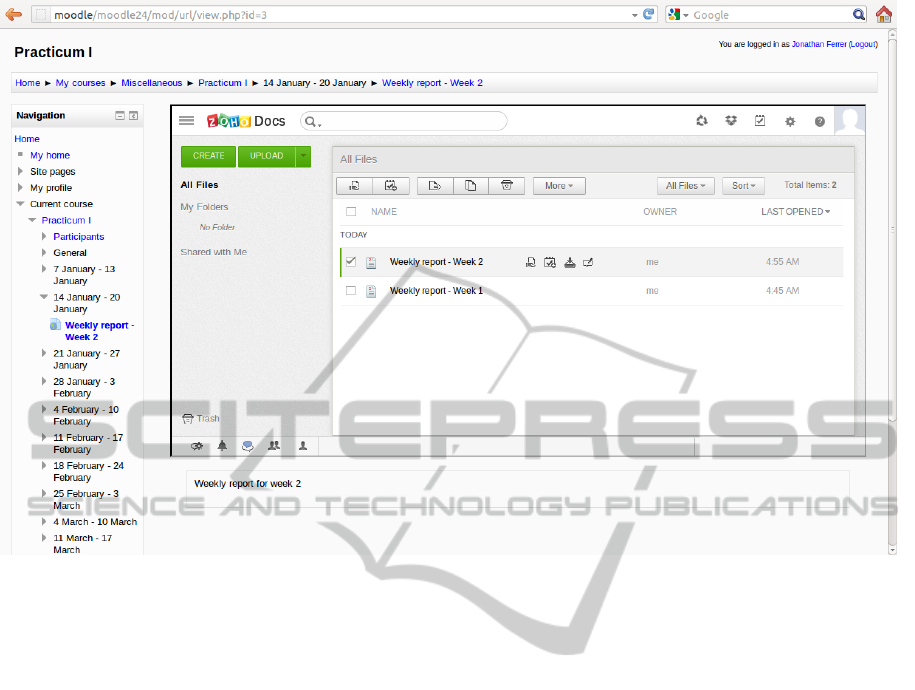

Figure 1: Example of the integration of Zoho Docs into Moodle as an embedded external link.

native tool of the LMS. This integration may imply,

for example, that log-in to an external site is done au-

tomatically from data stored in the user’s profile in the

local LMS, following the “single sign-on” approach

(SSO), without having to enter a new password.

One of the most popular LMS systems, the

Moodle platform, incorporates support for BLTI since

version 2.2. An example of a tool that makes use of

this support for integrating Google Drive, and in par-

ticular Google Docs, into Moodle is Docs4Learning

(Alier et al., 2012). On the other hand, Moodle pro-

vides a native module that allows the inclusion of

wikis, which can be considered a basic form of collab-

orative tool, as part of the materials for a course. Also,

the Moodle community has developed the Moodle-

Google plugin (Moodle Documentation, 2011), avail-

able since version 2.1 of Moodle, that provides direct

access to Google Apps, including Google Drive.

To the best of our knowledge, no implementations

of the BLTI interface are available as of today for the

other collaborative tools we mentioned above (Zoho,

Yammer, Asana). Following up our proposal, we plan

to evaluate the use of these tools within Moodle. If the

results of these evaluations are satisfactory, we will

implement the integration of the corresponding tool

or tools in Moodle via BLTI or with a specific plugin.

As an interim solution for the evaluation of the

tools, we can handle external objects in Moodle (e. g.

a Zoho Docs shared document) as external resources,

by inserting the links pointing to them. We have al-

ready applied this approach to the incorporation of

Google Drive documents into an instance of an older

version of Moodle, namely version 1.9, where it is

not straightforward to install the Moodle-Google plu-

gin (Perramon et al., 2012). Figure 1 shows an ex-

ample of a Zoho Docs folder of documents shared

between student and tutors, integrated as a resource

within a Moodle course using the external link tech-

nique. This solution has the advantage of being sim-

ple to implement, although it does not provide full

integration into Moodle. For example, it is necessary

to login separately to Moodle and then to Zoho Docs,

whereas a single sign-on solution would use the local

user credentials in the LMS for transparently signing

on to the external system. However, this arrangement

is sufficient for our purposes of evaluating the use of

the external collaborative tool.

Once the collaborative tool is integrated into the

LMS, we can use it like any other component of the

system. In particular, if the LMS provides an access

method from mobile devices, it will also be possible

to use it for accessing the collaborative tool. This is

the case of Moodle, for which various mobile appli-

cations have been developed, including an official app

(Moodle Documentation, 2014) and others with ex-

tended functionality, e. g. Moodbile (Piguillem et al.,

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

242

2012). Through these apps it is then possible to use

the collaborative tool embedded in Moodle from a

smartphone or a tablet, as is the goal of our proposal.

6 ADVANTAGES AND

DISADVANTAGES

The advantages of using collaborative tools have been

mentioned in Section 4 above. In our case, the use of

these tools in monitoring an out-of-classroom course

such as the Practicum has the benefit of facilitating a

smooth interaction between the three types of agents

involved: the student, the academic tutor and the ex-

ternal tutor.

When considering the individual tools, there is

not a single one that is clearly superior to the oth-

ers. Google Apps is probably one of the most pop-

ular, but Zoho and Asana have also a large user base.

Among their advantages, Asana is cited as having a

friendly user interface, appropriate for non-technical

users, while Zoho has been considered more robust

and stable, and offers more functionality, although

Google Apps is catching up, and probably even sur-

passing, as it is constantly evolving and upgrading in

a move to anticipate users’ needs.

We have also discussed in Section 4 the advan-

tages of using mobile applications, and specifically

in the case of out-of-classroom education in general

and the Practicum in particular. Mobile applications

are more and more widespread today, and apps are al-

ready available for Google Apps, Zoho, Asana, and

also for Moodle and other learning management sys-

tems.

With regard to disadvantages of collaborative

tools, especially those implemented as online ser-

vices, most are derived from the perceived negative

aspects of cloud computing technologies. A major

concern is related to security and privacy issues. In

the case of educational activities these issues are of

relative importance, since the privacy is not as critical

as in applications managing personal data or internal

company information.

Another issue with cloud-based tools is closely re-

lated to one of the advantages mentioned above. The

fact that application providers have an absolute con-

trol over the functionality offered by their services al-

lows them to upgrade the online applications to adapt

them to users’ requirements. However, they some-

times do so without previous notice, and may force

users to change usage habits when they would prefer

to continue working with the previous version of the

application with which they felt more comfortable.

As for mobile applications, their disadvantages

come from the particular characteristics of the mobile

devices: display size, touch-based input method, bat-

tery autonomy, network availability, etc. Obviously a

smartphone or a tablet is not the ideal device for writ-

ing a long report about the student’s activities, but it

is appropriate for taking short notes in situ that could

be otherwise forgotten when preparing the final re-

port. Da Silva et al. (2013) have performed a study of

the problems of mobile applications and web applica-

tions adapted to mobile access in the specific case of

e-learning environments. They conclude that a better

integration between devices and applications needs to

be explored to enhance the user experience.

7 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

We have presented a proposal for the monitoring of

a specific type of courses, in which all the learning

takes place outside the classroom as it is the case in

the Practicum or internship. This proposal is based

on collaborative tools for managing progress reports,

i. e. their preparation by students and their assessment

by tutors, to be accessed from mobile devices given

the external location of the learning process in these

courses. We have shown that the technology is al-

ready available and the devices are in widespread use,

and the implementation of our proposal is neither ex-

cessively complex nor expensive.

We plan to evaluate the use of different mobile

collaborative tools inside a LMS platform, namely

Moodle, and according to the results of this evalua-

tion we will implement the integration of the selected

tool, following simplicity and user friendliness crite-

ria.

REFERENCES

Alier, M., Casany, M. J., Mayol, E., Piguillem, J., Galanis,

N., Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo, F. J., and Conde, M.

´

A. (2012).

Docs4Learning: Getting Google Docs to work within

the LMS with IMS BLTI. Journal of Universal Com-

puter Science, 18(11):1483–1500.

Asana (n.d.). Asana – Teamwork without email. Retrieved

Feb. 5, 2014, from: http://asana.com/.

Carstensen, P. H. and Schmidt, K. (1999). Handbook of

Human Factors. Asakura Publishing, Tokyo.

Da Silva, A. C., Freire, F. M. P., and Da Rocha, H. V. (2013).

Identifying cross-platform and cross-modality interac-

tion problems in e-learning environments. In The Sixth

International Conference on Advances in Computer-

Human Interactions (ACHI 2013), pages 243–249.

UseofMobileCollaborativeToolsfortheAssessmentofOut-of-ClassroomCoursesinHigherEducation-Cloud

TechnologiesAppliedtotheMonitoringofthePracticum

243

Dr

˘

aghici, A., Burloiu, C.-A., Deaconescu, R., Karlsson, M.,

and M

¨

uller, D. (2013). Teamwork: A decentralized,

secure and portable team management system. In

IEEE 12th International Symposium on Parallel and

Distributed Computing (ISPDC), pages 182–189.

Google Inc. (n.d.). Google Apps for business. Retrieved

Feb. 5, 2014, from: http://apps.google.com/.

IMS Global Learning Consortium (2010). Basic learning

tools interoperability. Retrieved Feb. 5, 2014, from:

http://www.imsglobal.org/lti/.

Jaques, D., Gibbs, G., and Rust, C. (1993). Designing and

Evaluating Courses. Educational Methods Unit, Ox-

ford Brookes University, Oxford.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning. Prentice Hall

Inc., New Jersey.

Moodle Documentation (2011). Google Apps integration.

Retrieved Feb. 5, 2014, from: http://docs.moodle.org/

21/en/Google Apps Integration.

Moodle Documentation (2014). Mobile app. Retrieved

Feb. 5, 2014, from: http://docs.moodle.org/26/en/

Mobile app.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (2011). The

NIST definition of cloud computing. Retrieved Feb. 5,

2014, from: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/

800-145/SP800-145.pdf.

Neill, J. T. (2008). Enhancing Life Effectiveness: The Im-

pacts of Outdoor Education Programs. PhD thesis,

University of Western Sydney.

Perramon, X., Alemany, J., and Panad

`

es, L. (2012). As-

suring the quality of the Practicum in the EHEA with

Moodle and Google Docs. Design of a tool for facili-

tating the Practicum monitoring. In Proceedings of the

4th International Conference on Computer Supported

Education (CSEDU 2012), pages 175–178.

Piguillem, J., Alier, M., Casany, M. J., Mayol, E., Galanis,

N., Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo, F. J., and Conde, M.

´

A. (2012).

Moodbile: a Moodle web services extension for mo-

bile applications. In 1st Moodle Research Conference,

pages 148–156.

Reixa, M., Costa, C. J., and Aparicio, M. (2012). Cloud

services evaluation framework. In Proceedings of the

Workshop on Open Source and Design of Communi-

cation (OSDOC), pages 61–69.

Rodr

´

ıguez-Campos, L. (2012). Advances in collabora-

tive evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning,

35:523–528.

Trunity Holdings Inc. (2013). The Trunity eLearn-

ing platform. Retrieved Feb. 5, 2014, from:

http://www.trunity.com/company/.

Yammer Inc. (2014). Yammer: The enterprise so-

cial network. Retrieved Feb. 5, 2014, from:

http://www.yammer.com/.

Zoho Corp. (2013). 10 million users work online with Zoho.

Retrieved Feb. 5, 2014, from: http://www.zoho.com/.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

244