ETA Framework

Enterprise Transformation Assessment

Ricardo Dionísio

1

and José Tribolet

1,2

1

Department of Information Systems and Computer Science, Instituto Superior Técnico, University of Lisbon,

Avenida Rovisco Pais 1, 1049-00, Lisboa, Portugal

2

Centre for Organizational Design and Engineering, INESC INOV, Rua Alves Redol 9, 1000-029 Lisboa, Portugal

Keywords: Enterprise Transformation, η Framework, Stakeholder Engagement, Change Management, Benefit-Driven

Change, Enterprise Transformation Lifecycle.

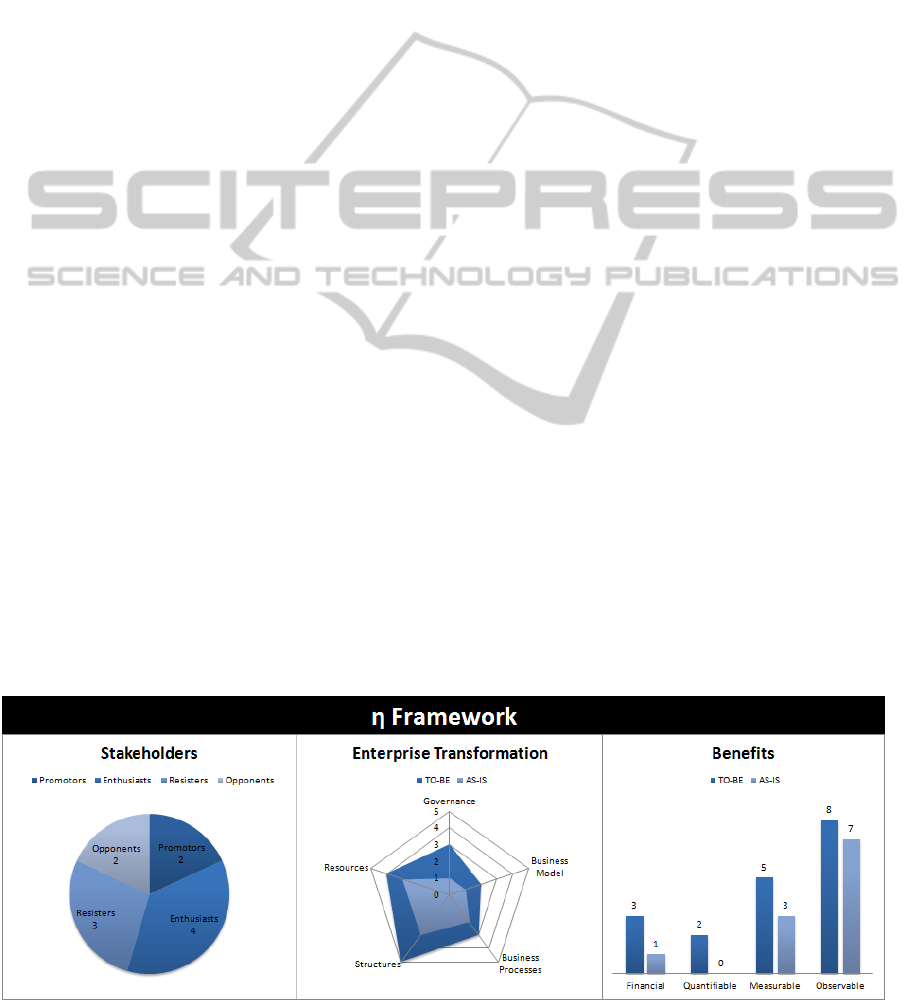

Abstract: In this paper we present the η Framework which aims at enabling a holistic vision of Enterprise

Transformation (ET) related to the adoption of Technological Artefacts. This framework is based on a

Benefit-Driven approach to ET led by Stakeholders. Therefore, we focus on three interrelated components:

(1) Stakeholders and corresponding classification according to their level of influence and attitude towards

an artefact; (2) ET which encompasses five dimensions, namely Governance Changes, Business Model

Changes, Business Process Changes, Structure Changes, and Resource Changes; and (3) Benefits classified

according to their different degree of explicitness and hence importance to each stakeholder. In order to

assess ET in a feasible way, we advocate mapping every single change with its corresponding benefit.

Subsequently, these pairs of changes and benefits are assigned to a group of “Change Owners”, who are

responsible for ensuring that ET is measured and successfully achieved. Finally, we summarize the four

phases of ET Lifecycle (Envision, Engage, Transform, and Optimise phase) as well as the corresponding

steps required to properly apply the η Framework.

1 INTRODUCTION

Successful adoption of Technological Artefacts

depends on implementing the appropriate change

(including governance or management of IT) in the

appropriate way. In many enterprises, there is a

significant focus on the first aspect - core

governance or management of IT - but not enough

emphasis on managing the human, behavioural and

cultural aspects of the change and motivating

stakeholders to buy into the change (ISACA, 2012)

(Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

It should not be assumed that the various

stakeholders involved in, or impacted by, new or

revised Technological Artefacts will readily accept

and adopt the change. The possibility of ignorance

and/or resistance to change needs to be addressed

through a structured and proactive approach. Also,

optimal awareness of the implementation program

should be achieved through a communication plan

that defines what will be communicated, in what

way and by whom, throughout the various phases of

the program (ISACA, 2012).

Sustainable improvement can be achieved either

by gaining the commitment of the stakeholders

(investment in winning hearts and minds, the

leaders’ time, and in communicating and responding

to the workforce) or, where still required, by

enforcing compliance (investment in processes to

administer, monitor and enforce). In other words,

human, behavioural and cultural barriers need to be

overcome so that there is a common interest to

properly adopt change, instil a will to adopt change,

and to ensure the ability to adopt change (ISACA,

2012).

Unfortunately, workers who are the majority of

stakeholders affected by the adoption of an artefact

are still instrumentally viewed as parts of the

enterprise “machine”. But this notion is starting to

change, especially in the Enterprise Engineering

community which advocates that (Dietz &

Hoogervorst, 2013):

─ Employees must be seen as a social group that

can significantly enhance enterprise effectiveness

and efficiency. Enterprises and corresponding

employees are systems that must be jointly

190

Dionísio R. and Tribolet J..

ETA Framework - Enterprise Transformation Assessment.

DOI: 10.5220/0004883101900200

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2014), pages 190-200

ISBN: 978-989-758-029-1

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

designed since they can mutually support each

other to enhance enterprise effectiveness and

efficiency;

─ The mere instrumental view on employees –

workers as labour resources – undervalues human

cognitive and social capacities.

This shift in focus considers employees, and their

involvement and participation, as the critical core for

enterprise success. Providing behavioural guidance

through shared purpose, goals, norms and values

ultimately boils down to providing meaning such

that individuals orient themselves to the

achievement of desirable ends (Uhl & Gollenia,

2012) (Dietz & Hoogervorst, 2013).

In a change process, some mistakes can happen

that sometimes are not even identified. Several

errors may occur in relation to the leadership of a

change. The most common mistakes that can occur

during ET are (Páscoa, 2012):

─ Investment allow excessive complacency;

─ Lack of a sufficiently powerful guiding coalition;

─ Underestimate the power of vision;

─ Inefficiently communicate the vision;

─ Allow new obstacles to vision;

─ Failure to create short-term wins;

─ Declare victory prematurely;

─ Neglect the incorporation of changes to the solid

culture.

In addition, due to the increasing amount of

shareholder value (and / or taxpayer’s money) that is

tied up in such transformations, one can expect that

the requirements on the transparency with which

these decision are made will increase (Proper &

Lankhorst, 2013).

Research surveys in over 200 international

organizations show that there is much that

organizations can gain from a comprehensive value

management applied throughout the transformation

lifecycle, mainly because a large percentage of

stakeholders are still not satisfied with their current

approach on (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012):

─ Identifying value and benefits (68%);

─ Investment business cases and benefit plans

(69%);

─ Managing the delivery of benefit plans (75%);

─ Evaluation and review of value realized (81%).

To address these issues we developed the η

Framework (which is pronounced as ETA

Framework, standing for Enterprise Transformation

Assessment Framework).

In the following Section 2 we describe this

framework in terms of its elements. Subsection 2.1

addresses Stakeholders Engagement and

corresponding stakeholder classification according

to their level of influence and attitude towards a

Technological Artefact. Subsection 2.2 presents

Enterprise Transformation Dimensions, namely

Governance Changes, Business Model Changes,

Business Process Changes, Structure Changes, and

Resource Changes. Subsection 2.3 addresses a

Benefit-Driven Change perspective where benefits

are classified according to their different degree of

explicitness and therefore how important they are for

each stakeholder. Finally, Subsection 2.4 explains

the goals behind mapping changes with benefits and

the importance of assigning them to “Change

Owners”.

Section 3 describes the four phases of ET

Lifecycle (Envision, Engage, Transform, and

Optimise phase) and the corresponding steps in each

phase required to properly apply the η Framework.

To sum up, we mention in Section 4 our main

conclusions.

2 ENTERPRISE

TRANSFORMATION

ASSESSMENT

The η Framework aims at enabling a clear

understanding of overall Enterprise Transformation

(ET) related to the adoption of Technological

Artefacts, by focusing on changes upon the

organization, corresponding benefits and stakeholder

engagement.

We advocate that the η Framework should be

used from the beginning until the conclusion of ET

projects. Notice that when we refer to an ET project

we mean “transformation process with the

purposeful intention to transform the organization as

a means to achieve some goal” (Tribolet & Sousa,

2013).

The η Framework is designed to be used in the

Operational Transformation Level, where we are

concerned with the day-to-day progress of the ET.

This level concerns the projects within the programs,

where the actual work of the transformation takes

place (Tribolet & Sousa, 2013).

As previously stated, stakeholders demand to

have a clear understanding of what changes will

happen upon their organization and the

corresponding benefits. Moreover, it is important to

align transformation-related objectives with goal-

setting and incentive systems (Uhl & Gollenia,

2012). This means that we should map each change

in the organization to its resulting benefits. By doing

ETAFramework-EnterpriseTransformationAssessment

191

so we can easily communicate with our project

stakeholders and explain to them why we are

adopting a certain Technological Artefact, namely

an Information System (IS).

The η Framework is depicted in Figure 1 and

encompasses three components, which are:

─ Stakeholders and corresponding classification

according to their level of influence and attitude

towards artefact;

─ Enterprise Transformation and its five

dimensions, namely Governance Changes,

Business Model Changes, Business Process

Changes, Structure Changes, and Resource

Changes;

─ Benefits and their different degree of explicitness,

which in ascending order are Observable,

Measurable, Quantifiable, and Financial benefits.

2.1 Stakeholders Engagement

Stakeholders are critical to the successful adoption

of the Technological Artefact since they can (and

often do) significantly influence its development and

outcome. The effective identification and

management of stakeholders is essential to the

success of ET (Nightingale & Srinivasan, 2011)

(Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

A project’s success is related to stakeholder

perceptions of the added value that is made possible

through ET both at large and for themselves in

particular, and also the nature of their relationships

as stakeholders with the artefact. Consequently,

stakeholder engagement is a critical success factor.

If stakeholders are not fully engaged it is likely that

there will be resistances to the implementation of the

artefact (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

The stakeholder management has the following

objectives (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012):

─ Identify and list all stakeholders who are

impacted by, or who can influence ET at the very

beginning of the design and deployment of the

artefact;

─ Conduct high-level change impact analysis that

the artefact will have on the current organization

and identified stakeholders;

─ Evaluate, analyze and record the degree of

support and importance of each stakeholder;

─ Align communication activities to reflect the

needs and demands of specific stakeholder

groups;

─ Manage stakeholder (groups) individually along

the artefact’s lifecycle.

Stakeholder management helps to anticipate

negative reactions to changes and supports to derive

appropriate strategies to overcome potential

resistances. At the beginning of ET all relevant

stakeholders have to be identified, described and

listed. This information helps to understand who are

affected by ET. The high-level ET impact analysis

provides information about the intensity of the

changes for each different stakeholder groups and

supports the anticipation of possible reactions.

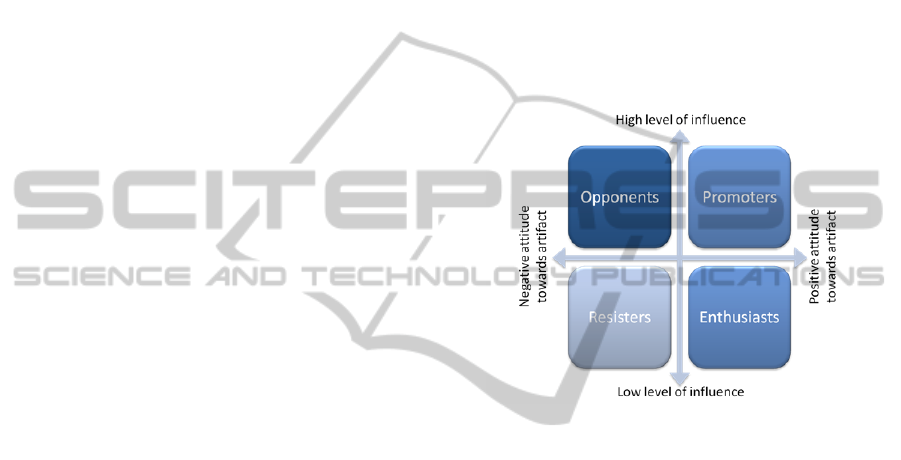

Afterwards, all relevant stakeholder groups are

evaluated and classified based on two dimensions

(Uhl & Gollenia, 2012):

─ Level of influence: This is the ability of the

identified stakeholders to influence the

deployment and operation of the artefact and is

determined using a high to low scale. For

example, a high level of influence can result in

decisions or actions from this stakeholder being

attributed to the success of the artefact and/or

leading to delays in timing, or may influence the

overall scope and/or resourcing related to the

artefact. A low level of influence means that the

stakeholders have little or no influencing power

over the progress or outcome of the artefact.

Figure 1: Example of applying the η Framework to an ET project.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

192

Nevertheless, it is still important to capture their

perceptions to minimize potential resistance;

─ Attitude towards artefact: This is the attitude of

the stakeholders towards the artefact and can

contribute to the successful adoption of it. A

negative attitude may lead the stakeholders to

withdraw support and actively seek ways of

working around it.

Therefore, each stakeholder can be classified as

one of four basic stakeholder classifications:

promoter, enthusiast, resister or opponent (Uhl &

Gollenia, 2012). These categories are explained in

the following subsections.

2.1.1 Promoters

Promoters are stakeholders who have been identified

as having a high level of influencing power and a

positive attitude towards the artefact. These

stakeholders can directly influence the scope of the

artefact and the progress to date; they can also

highly influence other people’s views on the

artefact. These stakeholders should be used as much

as possible to help promote the artefact to other

employees and to ensure that a “positive voice” is

being heard (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

2.1.2 Enthusiasts

Enthusiasts are stakeholders who have low influence

but a positive attitude can be used to help promote

the artefact and to gain support from other

employees. It should be made an effort to use them

as promoters (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

2.1.3 Resisters

Resisters are stakeholders with a low influence and a

negative attitude towards the artefact should not be

forgotten. Although their impact on the overall

success of the artefact is not critical, these

stakeholders should still be kept informed during

ET.

Stakeholders with a more positive attitude and

higher influence may be able to convert Resisters to

have a more positive attitude through regular

communication and adequate information to ensure

that these stakeholders understand the artefact and

become involved in ET (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

2.1.4 Opponents

Opponents are stakeholders who have been

identified as having a high level of influencing

power and a negative attitude towards the artefact

are also likely to be critical weakness to the

successful adoption of the artefact. Therefore, since

these stakeholders can directly influence the scope

of the artefact and its progress, and can highly

influence other people’s views on the artefact,

particular attention needs to be paid to them in order

to bring them on board with ET. It must be ensured

that ET does not face significant resistance. It may

be that these stakeholders do not fully understand

the artefact or why it is needed, or even do not feel

properly involved. No matter what the case is, their

issues must be addressed in order to prevent

spreading a negative attitude to other stakeholders

(Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

Figure 2: Stakeholder portfolio matrix (Uhl & Gollenia,

2012).

The stakeholder portfolio matrix helps to derive

organizational change management activities that

need to be taken to mobilize specific stakeholders

(especially opponents). These activities should be

targeted at enable stakeholder engagement, with the

purpose of increasing their commitment to ET and

consequently allowing ET to fulfil its benefits.

A revaluation of stakeholder groups on a

continuous basis helps to consider the ever-changing

environments of the artefact that will affect

stakeholder perceptions, interests, or priorities. In

addition, a reiteration of the stakeholder analysis

supports the measurement of the impact of the

applied artefact on the organization.

2.2 Enterprise Transformation

Dimensions

It must be assessed the high-level organizational

change impacts that an artefact will have on the

existing organization and corresponding

stakeholders. ET component gives a perspective of

the contribution/impact of a Technological Artefact

ETAFramework-EnterpriseTransformationAssessment

193

on each ET Dimension. We propose five dimensions

of ET, which are: Governance Changes, Business

Model Changes, Business Process Changes,

Structure Changes, and Resource Changes. Each of

them is explained below. Figure 1 depicts these

changes in a radar chart, enabling all stakeholders to

easily understand the overall impact of an artefact on

their organization.

2.2.1 Business Model Changes

Organizations appear as a response to the needs

presented by society. Since their appearance, their

business practice, irrespective of their activity,

should produce something in order to receive value

in return (Páscoa, 2012). A Business Model

“describes the rationale of how an organization

creates, delivers, and captures value” (Osterwalder

& Pigneur, 2009).

We may use any Business Model variant, still we

have opted for the Business Model Canvas

(Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2009). The Business Model

Canvas advocates the need of a business model

concept that everybody understands: one that

facilitates description and discussion. It is crucial to

start from the same point and talk about the same

thing. The challenge is that the concept must be

simple, relevant, and intuitively understandable,

while not oversimplifying the complexities of how

enterprises function. This concept can become a

shared language that allows you to easily describe

and manipulate business models to create new

strategic alternatives. Without such a shared

language it is difficult to systematically challenge

assumptions about one’s business model and

innovate successfully. Moreover, a business model

has nine basic building blocks that show the logic of

how an enterprise intends to create value

(Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2009).

The nine basic building blocks are (Osterwalder

& Pigneur, 2009):

─ The Customer Segments Building Block which

defines the different groups of people or

organizations an enterprise aims to reach and

serve;

─ The Value Propositions Building Block which

describes the bundle of products and services that

create value for a specific Customer Segment;

─ The Channels Building Block which describes

how a company communicates with and reaches

its Customer Segments to deliver a Value

Proposition;

─ The Customer Relationships Building Block

which describes the types of relationships a

company establishes with specific Customer

Segments;

─ The Revenue Streams Building Block which

represents the cash a company generates from

each Customer Segment (costs must be subtracted

from revenues to create earnings);

─ The Key Resources Building Block which

describes the most important assets required to

make a business model work;

─ The Key Activities Building Block which

describes the most important things a company

must do to make its business model work;

─ The Key Partnerships Building Block which

describes the network of suppliers and partners

that make the business model work;

─ The Cost Structure which describes all costs

incurred to operate a business model.

Business Model Changes encompass any

modification in the previous building blocks made

by the adoption of Technological Artefacts.

2.2.2 Governance Changes

Governance is the systems and processes put in

place to direct and control an organization in order

to increase performance and achieve sustainable

shareholder value. As such, it concerns the

effectiveness of management structures, including

the role of directors, the sufficiency and reliability of

corporate reporting and the effectiveness of risk

management systems (Páscoa, 2012).

Governance encompasses Authority,

Responsibility, Communication and Management.

Thus, Governance Changes are related to any

modification in these concepts.

2.2.3 Business Process Changes

Business Process Changes cover transformations

among “dynamically coordinated set of collaborative

and transactional activities that deliver value to

customers” (Páscoa, 2012).

2.2.4 Resource Changes

Resource Changes refer to modifications related to

materiel (equipment), information, human,

techniques, knowledge, skills and activities used to

convert raw materials to valuable resources for the

organization – or from a systems perspective, the

means by which inputs are transformed into outputs

(Páscoa, 2012).

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

194

2.2.5 Structure Changes

Structure Changes represent transformations in how

the organization is decomposed to best fit its goals.

It designates the formal reporting relationship in

number of levels and span of control, it identifies the

grouping together into departments (or sub-systems)

and of departments (or sub-systems) into the total

organization and it includes design systems to ensure

effectiveness, communication, coordination and

integration of efforts across departments (or

subsystems). An effective organization structure and

design is one that optimizes the performance of the

organization and its members by ensuring that tasks,

work activities and people are organized in such a

way that goals are achieved. An efficient

organization’s structure and design is one that uses

the most appropriate type and amount of resources

(e.g., money, materials, people) to achieve goals.

Structure is normally reflected in the organization

chart and is also the visual representation of the

whole set of underlying activities (included in

business processes) (Páscoa, 2012).

2.3 Benefit-Driven Change

It is important to have all key stakeholders interested

in the benefits provided by the artefact, motivating

them to contribute with their knowledge, influence

and time. Furthermore, it is crucial to obtain their

buy-in (or even better – engagement) regarding the

ET project by making clear why it is important.

Initially it is essential to capture the benefit in the

words that the stakeholders use, rather than in

generic or too much specific technical terms.

This allows to gain their commitment to achieving it

and to ensure its meaning is fully understood (Uhl &

Gollenia, 2012) (Bridges, 2003).

According to surveys made (Uhl & Gollenia,

2012), the more successful organizations include a

wide range of benefits, more than just Financial

Benefits, in their business cases. Benefits may be

Observable, Measurable, Quantifiable or Financial.

Table 1 shows a framework for structuring these

benefits according to the degree of explicitness. Any

benefit can be initially allocated to the “Observable

Benefits” row. Evidence must then be provided in

order to move it to the rows above, which represent

increasing levels of explicitness and knowledge

about the value of the benefit (Uhl & Gollenia,

2012).

Although some benefits are more difficult, but

not impossible, to quantify they enable to assess the

business value that many projects produce. The less

successful organizations tend to limit the benefits

included to those associated with efficiency

improvements and cost savings. Furthermore, while

some senior managers are primarily interested in the

financial benefits, many other stakeholders, such as

customers and employees can be more interested in

the “softer” or more subjective benefits (such as

observable ones). It is this last type of benefits,

rather than the financial ones that are likely to lead

to greater commitment from those stakeholders to

making the investment successful. Notice that the

sequence of expressing the benefits also matters,

which means that they should be ordered according

to the intended stakeholders if needed, mainly for

three reasons (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012):

─ Externally facing changes that will benefit

customers will have broader organizational

acceptance than changes that suggest benefits to

particular internal groups;

─ Positive and creative about new and better things

that will happen should come first, since they are

more likely to encourage action than negative or

reductionist changes;

─ The story around ET benefits being told should be

memorable, if the changes are truly worthwhile.

Nevertheless, having more than a few

simultaneous changes makes ET benefits too

difficult for most people to remember or even too

complicated for them to deal with ET.

It can be difficult to quantify the benefits of

implementation or improvement initiatives, and care

Table 1: Framework for structuring benefits (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

Degree of Explicitness Descriptio

n

Financial Benefits By applying a cost/price or other valid financial formula to a quantifiable benefit, a financial

value can be calcu lated.

Quantifiable Benefits Sufficient evidence exists to forecast how much improvement/value should result from the

chan ge.

M easurable Benefits This aspect of p erformance is currently being measured (or an app ropriate measure could be

implemented). But is not possible to estimate by how much p erformance will improve when the

chan ges are comp lete.

Observable Benef its By use of agreed criteria, specific ind ividuals/group s will decide, b ased on their experience or

judgment, to what extent the benefit has been realized.

ETAFramework-EnterpriseTransformationAssessment

195

should be taken to commit only to benefits that are

realistic and achievable. Studies conducted across a

number of enterprises that already have adopted the

identical artefact could provide useful information

on benefits that have been achieved (Uhl &

Gollenia, 2012). In addition, it should also be

provided a template of the η Framework with a

default mapping between expected changes and

corresponding benefits related to the adoption of a

specific artefact. This way it is easier for

organizations to fill in and understand how the

framework works. Nevertheless, it is essential to

adapt the η Framework to the organization’s reality

by adjusting changes and expected benefits.

As mentioned above, the benefits management

rationale is that benefits and changes are inextricably

linked and have to be considered at the same time,

rather than creating a list of benefits and later

working out how to achieve them. That is why it is

essential to have these two components (Changes

and corresponding Benefits) in the η Framework.

There is often some confusion between changes and

benefits: for example, “standardized or consistent

processes” are often quoted as a benefit, but in

reality are just changes; the benefit could be, for

example: “reduced loss of orders due to

unpredictable service levels” or “reduced staff

training costs”.

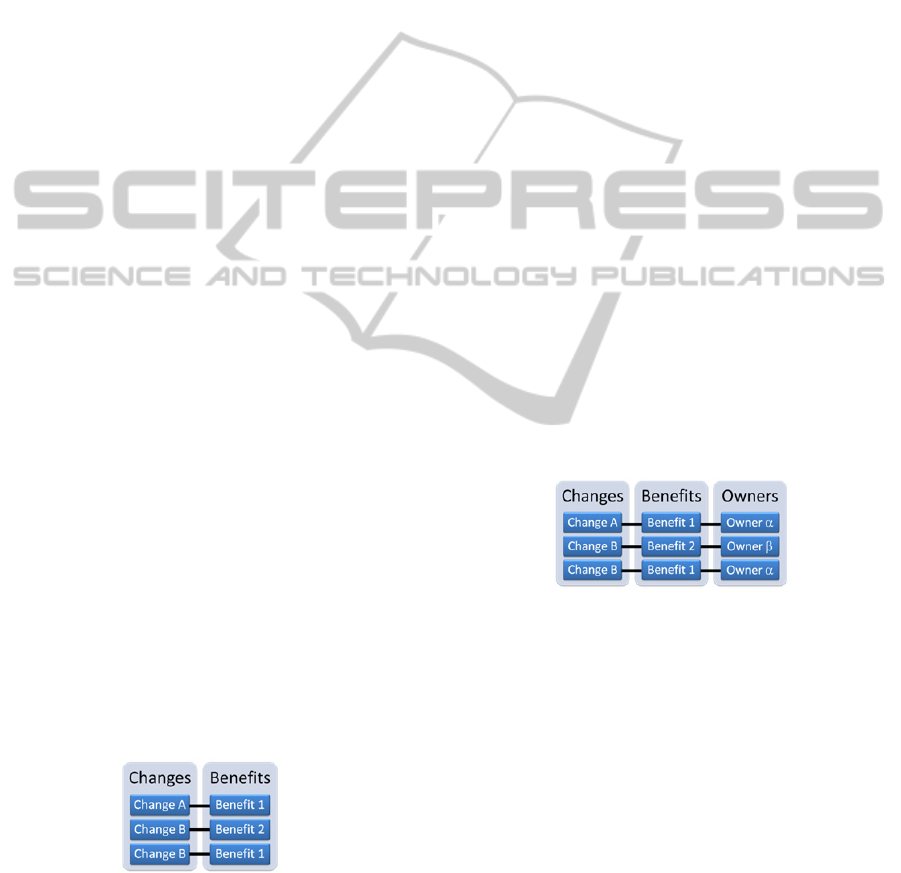

2.4 Mapping between Changes and

Benefits

The first goal when applying the η Framework is to

map all changes with corresponding benefits (Figure

3). Therefore we are able to easily answer the

following relevant questions related to the ET

leveraged by a Technological Artefact:

─ What are the expected changes?

─ What are the expected benefits?

─ What are the expected benefits for this specific

change?

─ Which changes enable this specific benefit?

Figure 3: Mapping between changes and corresponding

benefits.

2.4.1 Ownership

As initially stated, stakeholders’ involvement and

participation is a critical core for enterprise success.

Providing behavioural guidance through shared

purpose, goals, norms and values ultimately boils

down to providing meaning such that individuals

orient themselves to the achievement of desirable

ends (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012) (Dietz & Hoogervorst,

2013).

Selecting “Change Owners” to be responsible for

both changes and corresponding benefits is also an

essential aspect when applying the η Framework.

They are the cornerstones to define the AS-IS and

achieve the TO-BE. Therefore they help building a

robust and accurate ET against which success will

eventually be measured. In addition, an accurate

assessment of the current situation will normally

reveal priority areas of improvement within the

transformation and help schedule the changes to

deliver “quick wins” (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

“Change Owners” are those named individuals or

job role holders who accept responsibility for doing

all they can to make the changes happen

successfully, or to work with those making changes

to ensure that the benefits are achieved (Uhl &

Gollenia, 2012). Therefore, each pair of change and

corresponding benefit in the η Framework must have

an owner or in some cases joint owners (Figure 4).

This way we are also able to answer the following

relevant question:

─ Who is responsible for ensuring that changes and

corresponding benefits are achieved?

Figure 4: Mapping between changes/benefits and assigned

owners.

Furthermore, the role of these “Change Owners” is

to make sure that:

─ Change and corresponding benefit is achieved;

─ Define how the benefit is measured;

─ Decide whether it can be quantified and valued in

advance;

─ Define the current baseline (AS-IS);

─ Measure the extent to which it has been achieved

(update the AS-IS).

The η Framework allows having an accurate and

updated holistic vision of the ET, which increases its

credibility for many stakeholders, leading to greater

commitment and involvement in improving the

situation.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

196

2.4.2 Iterative Approach

Organizations are dynamic systems that are

constantly in motion. They change their purpose (for

instance, the core business of a company), their

customers and services, and their external and

internal structure in a pace that is much higher and

much less planned than it used to be. This is partly

due to the dynamic environment in which they

operate, but also, to a certain extent, a choice of their

own. To handle this motion, the successful

enterprises of today have well-defined managerial

responsibilities and understandable project priorities

while also enable the processes to be enough agile,

even improvisational and continuously changing. ET

therefore comprises more than just planned change,

initiated by people that think the organization is not

agile enough to respond to its environment – it is a

combination of deliberate and organic change.

Although previous research in the field of Enterprise

Transformation hardly expanded on “nonlinear

processes,” they do imply that to properly

understand ET one must allow for emergence and

surprise. Moreover, the possibility of ET must be

taken into account when having ramifications and

implications beyond those initially imagined or

planned (Harmsen & Molnar, 2013).

In sum, it is crucial to apply and update the η

Framework on a regular basis, from the beginning of

an ET project, through all outlined changes and

unexpected ones, until eventually all changes and

corresponding benefits have been successfully

achieved. At that point in time, one can expect

having the Technological Artefact entirely

operational and delivering its full potential to all

involved stakeholders.

3 APPLYING THE FRAMEWORK

ACCORDING TO ET

LIFECYCLE

This section illustrates how to correctly apply the η

Framework during an ET project related to the

adoption of a Technological Artefact by an

organization.

In order to successfully put into practice the η

Framework we must bear in mind the

Transformation Lifecycle, which provides an overall

map of the change territory and allows

understanding of the iterative nature of ET. Based

upon this, ET can be efficiently organized. The

mistake that hampers a smooth ET is considering the

transformation process as strictly linear; in essence,

the transformation process is iterative and goes

through different stages in recurring cycles.

Therefore, a stage model with recurring phases is

required (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012). Figure 5 depicts

the four steps encompassed in ET: (1) Envision, (2)

Engage, (3) Transform and (4) Optimize.

In the following subsections, we summarize the

four phases of the Transformation Lifecycle as well

as the corresponding steps required to properly apply

the η Framework. Moreover, the requirements and

expected outcomes of each phase are presented. It is

also explained why the selection of “Change

Owners” relies on their level of influence and

primarily on their attitude towards the artefact.

3.1 Envision

Envision is a phase that embraces the “why” as well

as the “how” questions of ET. “Why is change

needed and how capable is the organization to

manage the transformation?” This phase diagnoses

the need of the organization to adopt a

Technological Artefact. In addition, the strategy and

vision in dealing with the change need are also

developed. Thus, it combines both analytical

capabilities with creativity and foresight (Uhl &

Gollenia, 2012).

A further goal of the “Envision” phase is to

create stakeholders’ commitment to the developed

ET strategy within the top management team and

subsequently in middle management and employees.

For that reason ET must have a clear focus, be

objective and transparent (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012)

(Nightingale & Srinivasan, 2011).

Figure 5: ET Iterative Lifecycle (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

ETAFramework-EnterpriseTransformationAssessment

197

In this phase the main goal is to study the best

feasible option of a Technological Artefact to solve

a number of difficulties that the organization is

facing. After the artefact has been chosen, the team

responsible for this project should address it as an

ET project, monitoring the overall impact that this

artefact will have on their organization since the

moment it was chosen. The first step is to map all

related changes with corresponding expected

benefits. This enables them to adopt a holistic

approach to ET which must serve the “enterprise

value proposition” – the basic reason the whole

undertaking exists (Nightingale & Srinivasan, 2011).

This mapping is the cornerstone of sharing the sense

of urgency and vision of overall change in the

organization.

3.2 Engage

Engage phase represents mobilizing commitment in

the organization. Involvement and communication

are essential here, as well as the establishment of

discrete projects to deliver change and drive

momentum. Engagement would entail delivering

both behavioural and attitudinal buy-in to the

transformation (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012). For that, ET

requires a clear understanding throughout the entire

organization of what change is required, why it is

required, and what benefit will be obtained – which

is described in the mapping of changes and benefits

referred in the previous phase.

At this phase, identify relevant stakeholders

(such as managers and employees) and determine

their value propositions. These stakeholders must

support the adoption of the Technological Artefact

and believe in the benefits it will grant to the

organization – as well as to them. A comprehensive

analysis of all relevant stakeholders is difficult but

essential. First identify them and then prioritize each

(single or group of) stakeholder(s) (Nightingale &

Srinivasan, 2011) (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012). The

previously presented Stakeholder classification

allows categorizing, studying and selecting

stakeholders according to their attitude towards

artefact and level of influence.

On the one hand, it should be selected

stakeholders with a positive attitude towards the

artefact (such as promoters and enthusiasts) to

become “Change Owners”. Notice that each

“Change Owner” must comprehend the environment

in which “his/her” changes (and benefits) are taking

place, in order to be able to successfully monitor

them. Remember to keep demands reasonable. Do

not expect stakeholders to do more than is humanly

possible. Try to put them through only one

change/benefit at a time. If several changes are

going to happen simultaneously, prepare

stakeholders to cope with them and ensure that they

know how the whole picture fits together. In

addition, be prepared to scrap old rules. Drop

policies and ways of working that make the

transition harder than it has to be. And most

importantly, work with concise goals by setting

goals that are achievable, namely in the short term to

keep spirits up. Finally, keep communicating with

“Change Owners” and help them communicate

within the organization (Bridges, 2003).

On the other hand, stakeholders with a negative

attitude (such as resisters and opponents) must also

be addressed though in a different way. Take special

attention to opponents due to their high level of

influence. To make it as easy as it can be for these

stakeholders to put an end to what went before,

begin by forcing yourself (and your team) to see

clearly what is going to end and who is going to

suffer what losses as a result. Develop a strategy to

help them through the inevitable shocks (Bridges,

2003). Pay attention to their opinions and help them

to better understand changes/benefits that concern

them. Since benefits are classified according to their

level of explicitness related to the assessment of the

business value that a change produces to the

organization, it is possible to present the most

relevant benefits to each type of stakeholder. For

example, while some senior managers are primarily

interested in the financial benefits, many other

stakeholders, such as customers and employees can

be more interested in the “softer” or more subjective

benefits (such as observable ones) (Uhl & Gollenia,

2012).

3.3 Transform

Transform phase encompasses achieving all

previously defined changes, including Governance

Changes, Business Model Changes, Business

Process Changes, Structure Changes, and Resource

Changes in the organization. In this phase it is where

transformation in occurs, such as reorganization of

resources, new business processes and relationships,

including creating new business entities, relocation

and redeployment of staff, creating and utilizing new

capabilities and enhancing employee competencies,

and changing their behaviour, attitudes and shared

value. People need to understand the need for

transformation and commit to a pace which is

acceptable to them while enabling inhibiting walls

between departments and businesses to be removed.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

198

The rational and the emotional elements have to be

brought together to win hearts and minds (Uhl &

Gollenia, 2012). Only by then will the organization

be able to take full advantage from all efforts made.

Keep in mind to focus on enterprise effectiveness

before efficiency. An effective enterprise delivers

adequate value to all stakeholders. An efficient

enterprise operates at the lowest possible cost.

Efficiency has great value, but it is not the most

desirable quality. Effectiveness is crucial to

enterprise viability. Enterprises should strive to be

both effective and efficient, but lean organizations

are built on effectiveness (Nightingale & Srinivasan,

2011). The same applies to ET.

The main goal at this phase is to assess if each

change has been made and whether its

corresponding benefit has been achieved. As

previously stated, only afterwards we should focus

on increasing efficiency. Nevertheless, throughout

ET we must update the η Framework on a regular

basis in order to maintain a holistic and real model

of transformation occurring in the organization.

3.4 Optimise

Optimise is a phase where transformation must be

embedded and internalized as the new “business as

usual”. The institutionalization of transformation –

ensuring that quick wins are consolidated, processes

and achievements are measured, and any laggard

behaviour is addressed – will create conditions for

effective ET and ensure that change capability is

enhanced (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012).

It is crucial to ensure stability and flow within

and across the enterprise since it is unfeasible to

develop a useful baseline for ET amid turbulent

operations. Organizational stability helps identify

bottlenecks and eliminate them (Nightingale &

Srinivasan, 2011).

ET in practice is often messy and, to some

stakeholders engaged in it, as multiple activities vie

for attention and the realities of dealing with

obstacles confounds the best-laid plans. The iterative

nature of ET must therefore be addressed. The

constant iteration and the preparedness to return to

phases of the cycle to solve problems and reinforce

messages is a key element of the transformation

process (Uhl & Gollenia, 2012) – and this is where

the η Framework must excel.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we presented the η Framework which

aims at enabling a holistic vision of Enterprise

Transformation (ET) related to the adoption of

Technological Artefacts.

We discussed three interrelated components: (1)

Stakeholders and corresponding classification

according to their level of influence and attitude

towards an artefact; (2) ET which encompasses five

dimensions, namely Governance Changes, Business

Model Changes, Business Process Changes,

Structure Changes, and Resource Changes; and (3)

Benefits classified according to their different

degree of explicitness and hence importance to each

stakeholder.

In order to assess ET in a feasible way, we

proposed mapping every single change with its

corresponding benefit. Subsequently, these pairs of

changes and benefits are assigned to a group of

“Change Owners”, who are responsible for ensuring

that ET is measured and successfully achieved. The

selection of these “Change Owners” relies on their

level of influence and primarily on their attitude

towards the artefact, where promoters and

enthusiasts are fundamental to promote the artefact

and engage with other stakeholders in order to gain

their support.

Finally, we summarized the four phases of ET

Lifecycle (Envision, Engage, Transform, and

Optimise phase) along with the corresponding steps

in each phase required to properly apply the η

Framework. In addition, we stated that ET is an

iterative process, which must be applied and updated

on a regular basis.

In short, we proposed a Benefit-Driven approach

for Enterprise Transformation led by Stakeholders.

REFERENCES

Bridges, W., 2003. Managing Transitions: Making the

Most of Change, Perseus.

Dietz, J., Hoogervorst, J., and Al, 2013. the Discipline of

Enterprise Engineering. International Journal of

Organisational Design and Engineering, Vol.3, No.1,

Pp.86 - 114. Inderscience Publishers.

Harmsen, F. & Molnar, W., 2013. Perspectives on

Enterprise Transformation - a Sociological Meta-

Model for Transforming Enterprises. DC (Keynote)

Paper , 15th IEEE Conference on Business Informatics

– CBI 2013, Wien, July 2013, to Appear in a Special

Issue of the EMISA Journal (Enterprise Modelling and

Information Systems Architectures - an International

Journal), 2014.

COBIT 5, 2012 - a Business Framework for the

Governance and Management of Enterprise IT.

ISACA, 2012.

Nightingale, D. & Srinivasan, J., 2011. Beyond the Lean

ETAFramework-EnterpriseTransformationAssessment

199

Revolution, Achieving Successful and Sustainable

Enterprise Transformation. AMACOM – American

Management Association.

Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y., 2009. Business Model

Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game

Changers, and Challengers. John Wiley & Sons.

Páscoa, C., 2012. Organizational and Design Engineering

of the Operational and Support Dimensions of an

Organization: The Portuguese Air Force Case Study,

Instituto Superior Técnico, University of Lisbon: PhD

Thesis in Computer Science Engineering.

Proper, H. & Lankhorst, M., 2013. Enterprise Architecture

Management - Towards essential and coherent

sensemaking. DC (keynote) paper , 15th IEEE

Conference on Business Informatics – CBI 2013,

Wien, July 2013, to appear in a Special Issue of the

EMISA Journal (Enterprise Modelling and

Information Systems Architectures - An International

Journal), 2014.

Tribolet, J. & Sousa, P., 2013. Enterprise Governance and

Cartography. DC (keynote) paper , 15th IEEE

Conference on Business Informatics – CBI 2013,

Wien, July 2013, to appear in a Special Issue of the

EMISA Journal (Enterprise Modelling and

Information Systems Architectures - An International

Journal), 2014.

Uhl, A. & Gollenia, L. A., 2012. Business Transformation

Management Methodology, Gower Publishing.

ICEIS2014-16thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

200