Overcoming Cultural Distance in Social OER Environments

Henri Pirkkalainen

1

, Jussi P. P. Jokinen

1

, Jan M. Pawlowski

2

and Thomas Richter

3

1

University of Jyväskylä, Mattilanniemi 2, Agora Building, FI-40014 Jyväskylä, Finland

2

Ruhr West University of Applied Sciences, 45407 Mülheim, Germany

3

University of Duisburg-Essen, Universitätsstrasse 9, 45141 Essen, Germany

Keywords: Barriers, Culture, TEL, Cultural Distance, Social Software, OER.

Abstract: Open educational resources (OERs) provide opportunities as enablers of societal development, but they also

create new challenges. From the perspective of content providers and educational institutions, particularly,

cultural and context-related challenges emerge. Even though barriers regarding large-scale adoption of

OERs are widely discussed, empirical evidence for determining challenges in relation to particular contexts

is still rare. Such context-specific barriers generally can jeopardize the acceptance of OERs and, in

particular, social OER environments. We conducted a large-scale (N = 855) cross-European investigation in

the school context to determine how teachers and learners perceive cultural distance as a barrier against the

use of social OER environments. The findings indicate how nationality and age of the respondents are

strong predictors of cultural distance barrier. The study concludes with identification of context-sensitive

interventions for overcoming the related barriers. These consequences are vital for OER initiatives and

educational institutions for aligning their efforts on OER.

1 INTRODUCTION

Open educational resources (OERs) and practices to

increase the sharing behavior of both educators and

learners have been widely discussed in the domain

of technology-enhanced learning (TEL) in the recent

years. Online OER environments have been

receiving attention because they serve as platforms

for educators and learners to search and collaborate

in. While many initiatives have been rather

successful in keeping their OER environments in

linear growth with increased amounts of published

learning objects (Ochoa, 2009), maintaining active

participation in and use of the OER environments

remains the key challenge (Chen, 2010; D’Antoni

2008; Yuan et al., 2008). Existing research has been

discussing various barriers that hinder or negatively

affect OER adoption and use in teaching and

learning activities. Such barriers relate to lack of

awareness of OER and related copyright and

intellectual property issues (Chen, 2010; Yuan et al.,

2008; Hatakka, 2009), Institutional regulations and

restrictions (Yuan et al., 2008; Hatakka, 2009),

quality of resources (Hatakka, 2009; Richter &

Ehlers, 2011), and so on. As indicated by Chen

(2010) and Hatakka (2009), not all challenges

become significant, and barriers can be highly

context-dependent. Therefore, many challenges

could occur depending on the types of educational

practices in the region or country and depending on

the background, experiences, and perceptions of the

educators and learners. One of the crucial topics for

OER is cultural distance. As depicted by Hatakka

(2009), cultural expressions also pose a challenge

for understanding where language plays a strong role

in inhibiting factors of OER.

The OER movement must consider the

implications of knowledge sharing carefully, as

many initiatives are basing their OER services and

environments on social software-like functionalities

that place educators and learners as key users to

share, discuss, and collaboratively work on OERs

(Ha et al., 2011; Sotiriou et al., 2013). Knowledge

sharing is implying, in this case, not only sharing of

OER but also the collaborative practices around the

resources. The established connection between

social software and OERs to social OER

environments can have multiple potentials. As

indicated by research on social software in provision

of teaching and in pedagogy, these services can

provide positive learning outcomes and intriguing

experiences for both educators and learners when

applied to teaching practices (Hall & Davison, 2007;

15

Pirkkalainen H., P. P. Jokinen J., M. Pawlowski J. and Richter T..

Overcoming Cultural Distance in Social OER Environments.

DOI: 10.5220/0004719300150024

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 15-24

ISBN: 978-989-758-020-8

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Wever et al., 2007). However, the connection to

OER places educators even more in a key role in

OER environments with a strong focus on

functionalities for networking and collaboration.

Such environments build on international educator

and even learner communities, providing materials

across subject areas of the curriculum in various

languages. As elaborated by Lai and Chen (2011)

and Zhang (2010), adoption of specific social

software services might be highly country dependent

because of differences in culture and context. As

argued by Agarwal (2007), there are various

challenges to knowledge sharing while so-called

cultural distance becomes highly important in a

context where people deal within online social

environments. The finding is in line with the studies

of Noll et al. (2010) and Pallot et al. (2010) that deal

with collaboration across distance. However, the

current literature has been very limited in studies

that could inform the domain regarding how strong

those cultural barriers are perceived across nations,

within educator and learner communities that adopt

these social OER environments. Such information is

necessary for any educational institution or educator

evaluating the suitability of the OER environments

to own purposes. This information is also vital for

OER providers to understand the barriers for their

end users and the circumstances around those

challenges.

We address this gap by the means of a large-size

exploratory study (N = 855) to inspect how strongly

cultural distance barrier is perceived by teachers and

learners in primary and secondary schools across

Europe. Within our inspection, the aim is not to

define culture or different types of influencing

factors for it. However, we aim to understand in a

cross-national view to what extent teachers and

learners perceive cultural distance when dealing

with OER online social environments. In addition to

observing the barriers of cultural distance, our study

strives to understand possibilities to overcome such

barriers. These interventions are discussed on a

technical and nontechnical level to describe the

possibilities for OER content and technology

providers as well as educational institutions.

The structure of the paper is as follows. The next

section describes the theoretical background for

culture and social software focused OER. Then, we

will describe the methodology for the study. The

results are presented in the fourth section, followed

by the discussion of the results. The paper concludes

by describing the limitations of this study as well as

the key contributions to both research and practice.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

OER has been a widely discussed topic since 2002

when UNESCO coined the term in a global OER

forum. OER was described (2002) as “technology

enabled, open provision of educational resources for

consultation, use and adaptation by a community of

users for non-commercial purposes.” The research

on OER has been focusing on potential usage in

varying contexts, ranging from higher education

(Yuan et al., 2008) and schools (Richter & Ehlers,

2011) to the corporate world (Manisha &

Bandyopadhyay, 2009; Ha et al., 2011). Those

cross-context studies are often connected to barriers

or challenges that hinder OER adoption. These

barriers are discussed on various levels, on the

missing organizational support mechanisms (Chen,

2010; Yuan et al. 2008), lack of infrastructure and

proper hardware (Chen, 2010; Hatakka, 2009), lack

of quality of the resources as well as in the provided

services (Clements & Pawlowski, 2011), and so

forth. Existing research is yet to define in which

contexts and even in which countries or regions

certain barriers are likely to occur. One of the key

issues in the literature that could explain contextual

differences is culture and specifically, culture of

OER sharing (Davis et al., 2010; Richter, 2011).

As argued by Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952),

there is no definite concept of culture. Scheel and

Branch (1993) provided one possible description for

it as a manifestation of patterns of thinking and

behavior relating to social, historical, geographical,

political, economical, technological, and ideological

environment. Studying cultural factors or differences

for TEL is not an entirely new focus. Richter and

Pawlowski (2007) studied standardization of context

metadata within e-learning environments. They

defined cultural metadata and showed a number of

factors concerning language, which is one of the key

cultural factors. Those range from language,

communication style, specific symbols, attitudes and

perceptions of learners and educators, and culture-

specific idioms, to more technological issues, such

as types of date and time formats. As elaborated by a

number of researchers, studying cultural differences

can be problematic. Church and Katigbak (1988),

e.g., argue that while “one needs culture-comparable

constructs to make cross-cultural comparisons, their

use may distort the meaning of constructs in some

cultures or miss their culture-specific aspects.”

Goldschmidt (1966) even goes a step further,

claiming that it generally is inappropriate to compare

cultures at all, as every “institution” needs to “be

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

16

seen as a product of the culture within which it

developed. It follows from this that a cross-cultural

comparison of institutions is essentially a false

enterprise, for we are comparing incomparables.” As

a consequence, most culture comparisons are limited

to value systems, as there is a hope that there are

general values, which at least play a certain (even if

not exactly the same) role across most of the human

societies. However, in such investigations, the

position of the researcher rarely is neutral, as the

perspective taken to choose particular values for

comparison already is culturally biased. In a

multinational study, Schwartz and Bilsky (1990)

investigated 36 values in comparative culture

research and found that just seven of those had the

meaning of values across the investigated contexts.

In order to overcome this challenge, we focus on

educational contexts and define culture, according to

Oetting (1993), as “customs, beliefs, social structure,

and activities of any group of people who share a

common identification and who would label

themselves as members of that group” (herein,

perceptions of educators and learners in the

educational context).

Henderson (2007) described how the process of

preparation of e-learning materials demands the

analysis of cultural influence, especially when the

separation of local, national, and international

context of usage can be identified. Such separation

of contextual modes is becoming even more

prominent for OER as initiatives strive for

aggregation of existing repositories or databases in

one single access point (Ha et al. 2011; Sotiriou et

al., 2013). Additionally, social interaction and

collaboration mechanisms are crucial components of

such environments, and they increase cultural

influence. One way to address such cultural

influences is to focus on cultural distance. The

concept of cultural distance depends on the

recipient’s perceptions on how strong the difference

between the home culture and host culture are; the

greater the perceived difference, the more difficult it

is to establish a relationship (Ward et al., 2001). As

an example, such distance can be perceived when

educators or learners try to adopt OERs or teaching

practices that are exceptional or unfitting to their

own context. Another case of clashing home and

host culture could be when an educator is doubtful

of joining a relevant conversation with a colleague

from a distant location because it would not take

place in her mother tongue. Investigating cultural

distance provides information that crucially is

required to decide when conflicts may occur in OER

environments. In the context of OERs, cultural

distance becomes a highly relevant issue when

educators and learners shall use OERs from different

contexts; being constantly exposed to potential

learning materials and forms of collaboration that

may not fit to their own preferences of working and

learning or take place in their own native language.

Recent research in the educational domain shows

the increasing interest toward social software. Social

software can be described as a set of tools to enable

interactive collaboration, managing content, and

networking with others (Wever et al., 2007). While

the application of social environments has been

discussed as a support mechanism for pedagogy (Lai

& Chen, 2011; Hall & Davison, 2007), the

connection to OER is rather emerging. The focus of

social and collaborative services in OER

environments sets educators as key users of the

environments. Such “collaborative content

federations” (Ha et al. 2011; Sotiriou et al., 2013)

often provide materials in various languages, while

the environments are not equally translated to

support international users. While language skills

and preferences vary across educational level and

countries, the preferences of educators and learners

in terms of language or collaboration are not well

known. As elaborated by Agarwal et al. (2007),

knowledge-sharing activities of teachers and learners

can be highly influenced by culture. Similarly, Noll

et al. (2010) and Pallot et al. (2010) evidenced that

culture and language distance are two of the

strongest barriers in distributed collaboration, and

this sets the focus for our study.

OER as well as social software research focuses

on understanding particular barriers in order to

overcome them. Solutions and interventions have

been suggested as possible mechanisms to lower the

barriers (Chen, 2010; Yuan et al., 2008; Hatakka,

2009), such as technology and policy-related

strategies to be implemented (Chen, 2010) or short-

to long-term drivers or enablers from cooperation to

OER development (Yuan et al., 2008). Within this

paper, we aim to determine mechanisms for

lowering the barriers of cultural distance.

3 METHODOLOGY

Our study targeted school education, focusing on

teachers and learners in primary and secondary

schools across Europe. The aim was to find out 1)

how far cultural distance is perceived as a barrier

against the use of social OER environments, and 2)

how to overcome such barriers.

In our study, we first investigated cultural

OvercomingCulturalDistanceinSocialOEREnvironments

17

distance barriers in general, by asking teachers and

learners for their experiences regarding the use of

(selected) social OER environments; we wanted to

know which aspects in particular were understood as

the major barriers against the use of existing OER

environments. Second, we asked the participants to

determine the improvement potential for the

experimentally used social OER environments, in

order to identify possible interventions that would be

appropriate for overcoming the found barriers.

3.1 Operationalization of “Cultural

Distance Barriers”

To address cultural distance barriers and to observe

which aspects can predict its significance, a decision

was made to operationalize related barriers into this

one latent factor. The focus of the source literature

has not fully covered all of the barriers to a culture

of sharing and collaborating in OER environments.

As discussed, studying cultural influence factors in a

holistic setting is impossible because of the wide

variety of cultural aspects and the lack of knowledge

regarding their distinction (dependencies and

interrelations). The approach for the

operationalization and selection of related challenges

was set based on the previously presented

understanding of cultural distance by Ward et al.

(2001). For our investigation, we focused on barriers

that are related to aspects of sharing and

collaboration in social OER environments, the

language of collaboration, and the distance of the

identified OERs they come across.

As the found literature has not focused on social

OER environments, modification of approaches to

analyze barriers was necessary. A particular barrier

towards cultural distance that was found in the

literature was related to knowledge sharing and

collaboration (Noll et al., 2010; Pallot et al., 2010).

This barrier was related to language component of

cultural distance, as well as the perceived difference

of the home and host context. As a common

language is one of the greatest challenges for

organizing distributed work (Noll et al., 2010; Pallot

et al., 2010), we focused on this in our context. In

our setting, teachers and learners are connected

within an international community. The first item for

our survey was therefore: “Language is the key”. I

only want to contribute to online

communication/collaboration when my own native

language is used (based on Noll et al. (2010) and

Pallot et al. (2010)).

Richter & Ehlers (2011) and Hatakka (2009)

discussed that teachers might experience an

unmanageable distance when adapting resources

from other cultural contexts particularly regarding

language and culture-specific idioms. The second

item chosen for the survey was: Challenging to

apply digital educational resources which are

culturally distant (values, symbols, beliefs, etc.)

from my own (based on Hatakka (2009) and Richter

and Pawlowski (2007)).

Distance can also result from a lack of trust

against the authors of the OERs (Hatakka, 2009;

Pallot et al., 2010). While cultural distance can be

perceived without geographical or temporal distance

(Noll et al., 2010), the notion of geography was

included in the item to highlight the very likely

geographic dispersion of users in the social OER

environment. Thus, the third item was: Impact of

cultural and geographical distance - Lack of trust

towards authors of digital educational resources

(based on Hatakka (2009) and Pallot et al. (2010)).

Another important issue that derived from OER

research was that OERs often do not provide enough

information on the context where they were created

and designed for (Davis et al., 2010). This led to our

fourth item: Digital educational resources do not

give enough information on the context where it is /

was created and used (based on Davis et al. (2010)).

The focus was therefore set to study how the

participants perceive OER that is created in a

context that is distant from own, whether the

distance has impact on the trust for the authors and

providers of OER and if language plays a strong role

for collaboration. The starting point of our analysis

was, that these four culture barrier questionnaire

items were indicators of a single latent factor.

3.2 Data Collection

The data collection was conducted within the scope

of the Open Discovery Space project (ODS). The

ODS (Sotiriou et al., 2013) is an EU-funded FP7

project that builds a social OER environment for the

European school context around a federation of

learning content repositories. In the context of the

ODS project, workshops for teachers and learners

were organized. In the context of these workshops,

existing social OER environments were introduced:

OERs within their topics of teaching (and interest)

exemplarily were used, and the potentials for

adopting these environments were discussed. In the

end of the workshops, the participants were asked to

complete a questionnaire that addressed the

particular challenges the participants experienced in

this experiment and their expectations toward the

upcoming ODS portal. The role of each workshop

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

18

was to introduce the concepts addressed in the

questionnaire. This ensured that the respondents

were aware of what was asked from them.

One of the main parts of the ODS-questionnaire

focused on aspects that we addressed as being

related to cultural distance. The depth of the survey,

however, goes beyond the scope of this paper. The

instrument was operationalized with a total of 23

items and 10 open questions. Other parts of the

questionnaire addressed organizational and quality-

related OER-barriers that were derived from OER-

literature. The purpose was to see which barriers the

respondents perceive as most critical. The second

part of the survey included open questions asking for

enablers and interventions to overcome such

challenges. The inspection was solely limited to

perceived cultural distance because of its

significance in the analysis of both quantitative and

qualitative data.

Approximately 2300 educators and learners

participated in 92 workshops in 19 European

countries. While schoolteachers were mainly

expected to participate, ODS invited students,

educators from higher education as well as policy

makers to understand the restrictions and

possibilities for influencing the European education

system. The selection of schools was based on the

longitudinal engagement plan of ODS for the

schools of each country. Most of the workshops took

place in a face-to-face setting and were organized by

the local project partners. Four workshops were

conducted online through video conferencing

facilities. Each workshop focused on one or more

particularly selected OER environment(s). The main

criterion for the selection of the OER environments

was related to supported social functionalities

around the educational resources. The most

frequently demonstrated environments within the

workshops were:

OpenScout – OER for business and

management (http://learn.openscout.net)

OSR – Open science resources

(http://www.osrportal.eu)

Discover the Cosmos – Astronomy resources

(http://www.cosmosportal.eu)

Photodentro – A Greek Digital Learning

Object Repository

(http://photodentro.edu.gr/lor/)

In the study, 1175 individuals from 19 European

countries actually completed the questionnaire

(nonresponse rate of 49%). The countries were:

Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland,

Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania,

the Netherlands, Portugal, Serbia, Spain, and the

United Kingdom. The respondents were mainly

educators in primary, secondary, and higher

education. Additionally, a number of learners and

policy makers completed our survey. For the

analysis herein, we excluded policy makers and

participants representing higher education and only

considered the responses of teachers and learners

from primary and secondary school education

(N=855). The reason was to avoid mixing differing

contexts of higher education and schools together.

Additionally, the interventions could also be

discussed more accurately when restricting the focus

to a certain context. Some questionnaires were only

partially completed. Because this was particularly

the case in Romania, we finally excluded the

country’s participants from the evaluation. The mean

age of the respondents was 37.4 years (SD = 11.1).

Among the respondents, 69% were female, and 83%

were teachers.

3.3 Data Analysis

The previously discussed four questionnaire items

were used in constructing a summated scale to

represent the cultural distance barrier for the study at

hand. The reliability of the items was confirmed

using principal axis factoring. Factor loadings over

.50 were expected, as well as loadings relatively

comparable in size. The reliability coefficient of the

cultural distance scale was calculated using both

factor score covariance and Cronbach’s alpha. After

the reliability inspections, we proceeded to construct

a summated scale by calculating the average of the

four cultural distance barrier items. The average of

all variables was used instead of factor loadings,

because the study was exploratory and we wanted to

retain the original scale (from one to five). Any

missing values for the culture barrier items were

imputed to replace missing data. The amount of

missing values for the selected four items was

between 6.1% and 7.2%. Analysis of the missing

value patterns revealed no significant differences

between the gender and the role of the respondents.

To explore the country differences regarding

experienced barriers based on cultural distance, a

generalized linear model (GLM) predicting cultural

distance barrier was constructed. The fixed factors

of the model were, in addition to the country of the

respondent, the gender and professional status

(teacher or learner). The age of the respondent was

used as a covariate. An intercept was included in the

model, which was full factorial, e.g., interaction

effects between the fixed factors were also tested.

The second part of our study was to look for

OvercomingCulturalDistanceinSocialOEREnvironments

19

potential interventions against the cultural distance

barrier. This part of the survey applied open

questions purposing to understand what could solve

or lower the particular barriers reported by the

respondents. The following open questions were

applied to our survey for this purpose:

“HOW COULD TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS

AROUND RESOURCES SOLVE THESE PROBLEMS

(E.G., ONES PRESENTED TO YOU/WHICH YOU

TRIED IN THE WORKSHOP

)?”

“H

OW WOULD YOU IMPROVE THE CURRENT

SOLUTION

?”

“W

HAT KIND OF HELP/TRAINING/TOOLS

WOULD YOU NEED

?”

Our intention was to find solutions to overcome the

barrier of cultural distance. Key interventions

against cultural distance barrier were found through

clustering of the responses, which was accomplished

with a focus on technical and organizational issues.

The findings were understood as guiding steps for

the ODS implementation.

4 STUDY RESULTS

The factor loadings for the four culture barrier

questionnaire items that were derived in section 3.1

are displayed in Table 1. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

measure of sampling adequacy was .73, and

Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically

significant (p < .001). The single factor solution

displayed in Table 1 had an eigenvalue of 2.2, and

explained 56% of the variance of the four cultural

distance barriers. The reliability of the scale using

factor score covariance was .74, and Cronbach’s

alpha was .72. The mean of the summated scale of

culture barrier, calculated as the mean of the four

items, was 2.65 (SD = 0.95), and both its theoretical

and observed range was 1.00–5.00.

The results of the general linear model predicting

the barrier of cultural distance are displayed in Table

2. The number of observations for GLM was smaller

than for Principal Axis Factoring, because six

respondents had failed to report their age and were

therefore removed from this analysis. From the main

effects, age and country were statistically

significant. Gender, role (teacher/learner), and the

interaction effects between the fixed factors were

nonsignificant. The coefficient of the model

intercept was 1.88, and the upper and lower bounds

of 95% confidence interval were 1.50 and 2.29, p <

.001. The coefficient of the age was.01 [.01, .02], p

< .001. In other words, the older participants were

more likely to report a higher barrier of cultural

distance.

Table 1: Factor loadings for principal axis factoring of

cultural distance barrier items.

Item

Loading

Challenging to apply digital educational

resources which are culturally distant (values,

symbols, beliefs etc.) from my own.

.71

Impact of cultural and geographical

distance - Lack of trust towards authors of

digital educational resources.

.69

Digital educational resources do not give

enough information on the context where it is /

was created and used.

.58

“Language is the key.” I only want to

contribute to online

communication/collaboration when my own

native language is used.

.54

Note. N = 861.

Table 2: General linear model predicting cultural distance

barrier.

Source df F sig.

Corrected Model 55 3.6 < .001

Intercept 1 227.3 < .001

Age 1 15.8

< .001

Gender 1 2.9 .088

Country 17 4.7

< .001

Role: teacher/learner 1 1.5 .227

Gender × country 17 1.0 .483

Gender × role 1 2.6 .111

Country × role 11 0.8 .581

Gender × country × role 6 0.4 .867

Note. N = 855. Model R squared = .20, adjusted = .14.

The GLM revealed how the cultural distance

barrier depends on the nationality and age of the

respondent. Results also indicated how the roles of

teacher or learner do not explain the barrier of

cultural distance. This implies that teachers are not

more likely to perceive cultural distance barrier than

learners and vice versa. The mean of the cultural

distance barrier variable for learners was 2.52 (SD =

1.03), and for teachers 2.68 (SD = 0.93). For both

males and females, the mean was 2.65, and standard

deviations, respectively, were 0.93 and 0.96. The

findings imply that the perceived cultural distance is

not a barrier for majority but is likely to occur

depending on the age and nationality of the

teacher/learner.

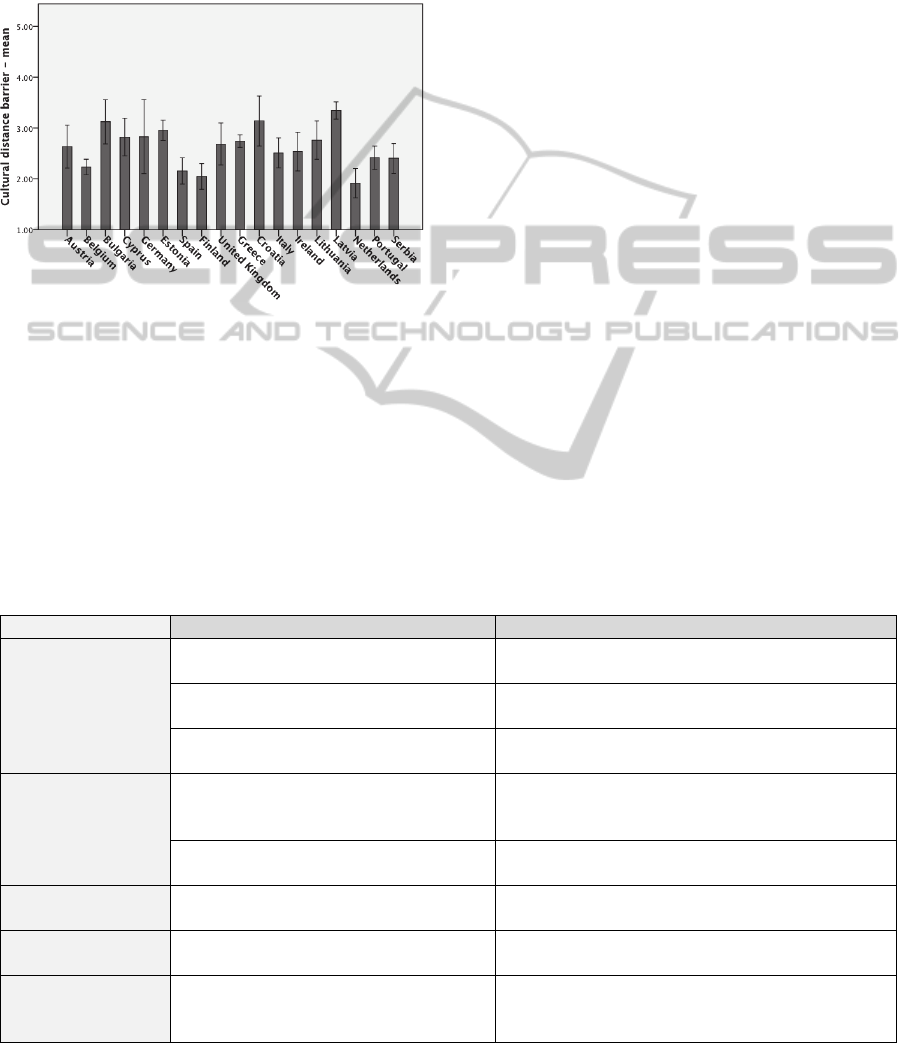

The means of the cultural distance barrier

variables between the countries are shown in Figure

1. Based on post-hoc analysis (least significant

difference) we identified Croatia, Latvia, and

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

20

Estonia to be the countries with statistically

significantly high means as compared to the

countries with relatively low means: Austria,

Belgium, Spain, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands,

Portugal, and Serbia. The implications of these

results will be discussed in the last section of this

paper.

Figure 1: Country separation for cultural distance barrier.

Smaller lines denote 95% confidence interval.

5 INTERVENTIONS

As previously explained, our research was not

limited to investigating which parameters

particularly affect cultural distance. In addition, we

also studied interventions for the corresponding

barriers. The answers we received on the open

questions asking for potential mechanisms to

overcome the barriers were related to both

technological and organizational/contextual levels:

Overcoming cultural distance barrier, firstly, regards

the quality and suitability of the OER environment

(technology) and, secondly, the community and

OER initiatives themselves, as they act as change

enablers toward new practices of sharing. In Table 3,

both aspects for interventions are discussed.

In addition to the technical interventions, the

respondents made recommendations to remove the

barriers on the organizational level as well as the

OER community-level (Table 4).

The results on interventions to potentially

overcome or reduce barriers that are related to

cultural distance indicate the key opinions of

teachers and learners of our study. As shown in the

technical dimension, the provision of functionalities

as well as the variety of resources has to match the

particular requirements and needs of the individual

users. As presented in the previous section, not all

users in the different European countries have the

experience or are able to collaborate in a foreign

language or to adopt OER that might be culturally

distant. The key intervention seems still to be

stimulating a change in OER knowledge-sharing

practices by leading examples through the

engagement and training activities of the OER

initiatives that also provide the OER environments.

Table 3: Technical interventions.

Key aspect Explanation

Multilinguality

Resource availability in own native

language

Many are unwilling or cannot handle foreign

language

Equal distribution of materials in

different languages

Users need to have materials that are easy for them

to apply

Portal translated to own language

Shows that their language is important for the

provider/developer

Functionalities

Methods for communication/

collaboration

Synchronous/asynchronous,

Formal/informal

Sharing and collaborating

With anyone,

With selected people/group/community

User interface

Intuitive and localized for specific user

groups

Providing customized views for s/learners from

different countries/regions

Metadata

provision

Rich and versatile metadata

E.g., indicating clearly for each resource, the

context where it is created/used

Trusted

communities

Quality mechanisms, indicating when

resources are from reliable and active

source

Aiming to increase trust toward user-/- generated

content

OvercomingCulturalDistanceinSocialOEREnvironments

21

6 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

Within this paper we investigated the perception of

cultural distance as a barrier against the use of social

OER environments and ways to overcome those

barriers. The perceptions of teachers and students

from school education were in key role for defining

whether they feel such cultural distance when using

OERs and collaborating with international

communities around those OERs. Our study focused

on barriers against social software services that are

provided for/within OER environments, creating

social OER environments. As the understanding on

how cultural distance barrier is perceived and how to

overcome related challenges was rather limited, the

findings of this study can provide a significant

contribution to fill this gap. The results indicate how

age and nationality affect the significance of cultural

distance barrier. Younger respondents are more

likely to experience a lower level of barrier when

dealing with learning resources from and online

collaboration with a distant culture. The results also

evidence which of the 18 investigated countries’

participants perceive cultural distance as a barrier.

Interestingly, the professional role of the

respondents did not significantly affect the

perceptions towards cultural distance barrier.

The findings indicated that cultural distance is

statistically significantly perceived as a barrier,

particularly in the Baltic countries of Latvia and

Estonia, and in Croatia. However, our study cannot

explain why some countries had relatively low

means in this context (e.g., Belgium, Spain, Finland,

and the Netherlands). More research is needed to

indicate the general validity of our results as well as

to explain the reasons for the between-country

deviations. While one argument could be that

language skills and preferences differ between

countries, such results might also be explained by

awareness on OER in general. If the schools have a

strong background in using textbooks, a rapid

change to apply and modify OERs provided by an

international community might not be realistic or

trivial. Such a basic change of thinking and towards

practical ways to approach preparation of lectures

and teaching can be problematic. However, the

findings do indicate how applying OERs that are

prepared in/for a specific national/educational

context might raise even more significant barrier

within another context.

The influence of age regarding the perceived

impact of cultural distance barrier is an important

finding as it has not yet been reported in the context

on OER. However, Onyechi and Abeysinghe (2009)

reported similar results regarding the use of

technology; they found that users under 35 years old

are more likely to accept collaborative tools.

Regarding interventions against barriers that are

related to cultural distance, we found both technical

and nontechnical issues. The respondents elaborated

on how social OER environments must fulfill their

basic needs in terms of the quality of provided

services and resources, and multilinguality. In order

to generally reach a higher level of acceptance, OER

initiatives should not just provide the technology

Table 4: Nontechnical interventions.

Key aspect Explanation

Translating/localizing

resources to fit the context

Setting a group within small communities and schools to translate the best materials

for that purpose into their own language. Setting contests that include

translation/localization/adaptation tasks, rewarded by the ODS network in cooperation

with the local schools. Rewards could be free access to events such as summer school,

training events, or conferences.

OER initiative

stimulating the creation of

knowledge-sharing

culture in schools

Teacher’s practices still vary for sharing their resources as well as using resources

provided by others, even within their own schools. This process should happen from the

bottom-up and then expand to the European level. To create this culture of sharing

resources, experiences, and competencies with others, the OER initiatives should motivate

teachers on local, national, and international levels to do so by showing some good

examples of collaboration across countries.

OER initiatives should aim to be open communities focusing on support and

experience exchange. Teachers and learners should feel a sense of belonging and be given

something that they feel comfortable using. Otherwise they might feel afraid that they’ll be

criticized about what they wrote or contributed.

OER initiatives should provide opportunities for teachers to attend international

training events, in order to help overcome cultural barriers in trusting resources from

different cultures, as well as to feel that they are members of an international community.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

22

for the OER usage but additionally foster the change

toward openness in education. In this context,

intense cooperation with the schools is required, e.g.,

approaching joint campaigns and collaborative

efforts to contextualize/translate OERs for the

contexts of the schools.

Our study and the related results have

limitations: First of all, our results need to be limited

to the context of school education, where the

research took place. It is yet unclear to which extent

those can be transferred to other educational

scenarios. The participating schools were selected

from existing networks of the partner organizations

in the project. In many cases, only teachers from one

specific area of the country participated. Thus, the

sample might not be fully representative for all

schools in the country. Additionally, we did not

investigate the previous experience of the

participants with OER. In retrospective, this might

have been valuable information for both the analysis

as well as the interpretation of the actually received

results. We do acknowledge that the actual barriers

differ between teachers in different contexts and

educational institutions. However, this study focused

on understanding to which extend teachers perceive

cultural distance barrier when using OER

environments, not to explain the types of barriers

teachers face nor various cultural influencing factors

that affect their behavior.

As the research was conducted as a part of the

requirements analysis for the development of the

social OER environment for the ODS project, the

practical implications of our study are clear,

especially for OER providers and developers: The

results are relevant for any engagement activities

with teachers and learners in similar OER scenarios.

As OER provision through resource-/repository-

federations becomes even more frequent, our results

support the decisions on how to overcome some

typical challenges. The results also give pragmatic

suggestions to engage through the younger teachers

as early adopters and community builders. Our

findings can therefore help to significantly reduce

efforts placed for the identification of needs and

requirements of teachers and learners during the

development of social OER environments.

Our contribution to research lies in the

exploratory factor analysis conducted within this

study. The identification of the factors representing

barriers that are related to cultural distance provides

a meaningful construct for future quantitative studies

on OERs. Future studies on the topic could apply the

proposed construct on variance models to verify and

enrich existing theories on, e.g., technology

acceptance. It would be important to address further

studies to explain which barriers (e.g., lack of

support within the organization, lack of awareness

on OER) can predict barriers on the level of cultural

distance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been co-funded by the European

Commission through the CIP programme, Open Dis-

covery Space, CIP-ICT-PSP-2011-5 297229 (cf.

http://www.opendiscoveryspace.eu).

REFERENCES

Agarwal, N., Tan, K., & Poo, D. (2007). Impediments to

Sharing Knowledge Outside the School: Lessons

Learnt From the Development of a Taxonomic E-

learning Portal. International Conference on

Information Systems.

Chen, Q. (2010). Use of Open Educational Resources:

Challenges and Strategies. Hybrid Learning, 339–351.

Church, T. A. & Katigbak, M. S. (1988). The Emic

Strategy in the Identification and Assessment of

Personality Dimensions in a Non-Western Culture.

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 19, 140-163.

Clements, K. I., & Pawlowski, J. M. (2011). User oriented

quality for OER: Understanding teachers ’ views on

OER and quality. Journal of Computer Assisted

Learning, 2007–2009.

Davis, H. C., Carr, L. a., Hey, J. M. N., Howard, Y.,

Millard, D., Morris, D., & White, S. (2010).

Bootstrapping a Culture of Sharing to Facilitate Open

Educational Resources. IEEE Transactions on

Learning Technologies, 3(2), 96–109.

D’Antoni, S. (2008). Open Educational Resources

Deliberations of an international Community of

Interest. Retrieved from: https://

oerknowledgecloud.org/sites/oerknowledgecloud.org/f

iles/Antoni_OERTheWayForward_2008_eng_0.pdf.

Goldschmidt, W. (1966). Comparative functionalism.

University of California Press, Berkeley.

Ha, K., Niemann, K., Schwertel, U., Holtkamp, P.,

Pirkkalainen, H., Boerner, D., Kalz, M., et al. (2011).

A novel approach towards skill-based search and

services of Open Educational Resources. Metadata

and Semantic, 1–12. Retrieved from http://

www.springerlink.com/index/W7667752J630Q7U3.pd

f.

Hall, H., & Davison, B. (2007). Social software as support

in hybrid learning environments: The value of the blog

as a tool for reflective learning and peer support.

Library & Information Science Research, 29(2), 163–

187.

OvercomingCulturalDistanceinSocialOEREnvironments

23

Hatakka, M. (2009). Build it and they will come?–

Inhibiting factors for reuse of open content in

developing countries. The Electronic Journal of

Information Systems in Developing Countries, 37, 1–

16.

Henderson, L. (2007). Theorizing a multiple cultures

instructional design model for e-learning and e-

teaching. Globalized e-learning cultural challenges.

Kroeber, A. L. & Kluckhohn, C. (1952). Culture: A

Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Vintage

Books, New York.

Lai, H.-M., & Chen, C.-P. (2011). Factors influencing

secondary school teachers’ adoption of teaching blogs.

Computers & Education, 56(4), 948–960.

Manisha, & Bandyopadhyay, T. (2009). A case study on

content sharing by leveraging open educational

resources framework. 2009 International Workshop on

Technology for Education, 116–119.

Noll, J., Beecham, S., & Richardson, I. (2010). Global

software development and collaboration: barriers and

solutions. ACM Inroads, 1(3), 66–78.

Oetting, E. R. (1993). Orthogonal Cultural Identification:

Theoretical Links Between Cultural Identification and

Substance Use. Drug Abuse Among Minority Youth:

Methodological Issues and Recent Research

Advances. 32-56.

Ochoa, X., & Duval, E. (2009). Quantitative Analysis of

Learning Object Repositories. IEEE Transactions on

Learning Technologies, 2(3), 226–238.

doi:10.1109/TLT.2009.28.

Onyechi, G. C., & Abeysinghe, G. (2009). Adoption of

web based collaboration tools in the enterprise:

Challenges and opportunities. 2009 International

Conference on the Current Trends in Information

Technology (CTIT), 1–6.

Pallot, M., Martínez-Carreras, M. A., & Prinz, W. (2010).

Collaborative Distance. International Journal of e-

Collaboration, 6(2), 1–32.

Richter, T. (2011). Adaptability as a Special Demand on

Open Educational Resources: The Cultural Context of

e-Learning. European Journal of Open and Distance

Learning.

Richter, T., & Ehlers, U.-D. (2011). Barriers and

Motivators for Using OER in Schools. eLearning

Papers, 23(March), 1–7.

Richter, T. & Pawlowski, J. (2007). The need for

standardization of context metadata for e-learning

environments. e-ASEM Conference, Seoul, Korea.

Scheel, N. & Branch, R. (1993). The role of conversation

and culture in the systematic design of in-struction.

Educational Technology. 33, 7-18.

Schwartz, S. H. & Bilsky, W. (1990). Toward a theory of

the universal content and structure of val-ues:

Extension and Cross-Cultural replications. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychol-ogy. 58, 878-891.

Sotiriou, S. A., Agogi, E., Athanasiades, N., Ramfos, A.,

Stracke, C. M., Richter, T., Pirkkalainen, H., et al.

(2013). Open discovery space. Retrieved from:

http://www.opendiscoveryspace.eu/sites/ods/files/open

_discovery_space.pdf.

UNESCO. (2002) UNESCO promotes new initiative for

free educational resources on the Internet. Retrieved

from: http://www.unesco.org/education/news_en/

080702_free_edu_ress.shtml [19 May 2012].

Ward, C. A., Bochner, S. & Furnham, A. (2001). The

psychology of culture shock. Hove: Routledge.

Wever, B. De, Mechant, P., Veevaete, P., & Hauttekeete,

L. (2007). E-Learning 2.0: Social Software for

Educational Use. Ninth IEEE International

Symposium on Multimedia Workshops (ISMW 2007),

511–516.

Yuan, L., MacNeill, S., & Kraan, W. (2008). Open

Educational Resources – Opportunities and Challenges

for Higher Education Open Educational Resources –

Opportunities and Challenges for Higher Education.

JISC CETIS, 1–35.

Zhang, L. (2010). Adoption of social software for

collaboration. Proceedings of the International

Conference on Management of Emergent Digital

EcoSystems, 246–251.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

24