Data Curation Framework for Facilities Science

Vasily Bunakov and Brian Matthews

Scientific Computing Department, Science and Technology Facilities Council, Harwell OX11 0QX, U.K.

Keywords: Research Data, Research Lifecycle, Data Curation, Big Data, Linked Data.

Abstract: The trend in research data management practice is that the role of large facilities represented by particle

accelerators, neutron sources and other scientific instruments of scale extends beyond providing capabilities

for the raw data collection and its initial processing. Managing data and publications catalogues, shared

software repositories and sophisticated data archives have become common responsibilities of the research

facilities. We suggest that facilities can further move from managing data to curating them which implies

meaningful data enrichment, annotation and linkage according to the best practices which have emerged in

the facilities science itself or have been borrowed elsewhere. We discuss the challenges and opportunities

that are the drivers for this role transformation, and suggest a data curation framework harmonized with the

research lifecycle in facilities science.

1 INTRODUCTION

The growth of research complexity, the increased

costs of the advanced scientific instruments, and the

internationalization of science have led to the

emergence of research facilities that can be thought

of as well-equipped hubs where research teams

come to perform their experiments, often associated

with other experiments in the same or other research

centres.

The research facility core is typically represented

by a unique scientific instrument: a particle

accelerator, a neutron source, a powerful laser, a

telescope, or a supercomputer that allows detailed

simulation of natural phenomena, or by a few such

instruments that offer researchers different

experimental techniques. Examples would include

the Diamond Synchrotron Light Source

(www.diamond.ac.uk), ISIS neutron source

(www.isis.stfc.ac.uk) or the future Square Kilometre

Array (www.skatelescope.org). The exact boundary

between basic and applied research on such facilities

may be ill-defined, e.g. the same electron

synchrotron may be used part time to explore the

fundamental effects of particle collisions and part

time as the source of synchrotron radiation for

materials science, biology and pharmaceutics. For

the sake of clarity, we use the term “facilities

science” for the research performed on large-scale

scientific instruments by visitor teams or individual

researchers who obtain, via the application process,

access to the common facility resource in order to

conduct their experiments or observations, and to

collect the resulting data.

The instruments and experimental techniques

may be different between facilities; the purpose of

research may be more inclined to scientific inquiry,

or more practical in view of industrial applications.

What is common across facilities science is a

business model for servicing the facility users

(researchers); the users’ social habits, e.g. the

accepted modes of managing research output, are

less definitive but also important. These

commonalities lay a foundation for a generic data

lifecycle in facilities science, as well as for common

metadata models and information systems

architecture.

Our modelling and implementation effort in

respect to supporting the facilities’ data lifecycle is

mentioned in this paper but we concentrate on

challenges and opportunities that the facilities

science business model and the researchers’ social

attitudes present for data curators and technologists;

we then discuss a framework that should address

these challenges and opportunities.

211

Bunakov V. and Matthews B..

Data Curation Framework for Facilities Science.

DOI: 10.5220/0004593302110216

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Data Technologies and Applications (DATA-2013), pages 211-216

ISBN: 978-989-8565-67-9

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 CHANGING LANDSCAPE

OF FACILITIES SCIENCE

The evolving changes in business model, technology

and facilities users’ behaviour are all interrelated and

result in new challenges and new opportunities for

the facility science stakeholders, specifically for data

curators and IT specialists.

2.1 Changes in Business Model,

Technology, and user Behaviour

A business model for user research on large facilities

that emerged more than 50 years ago has been

influenced by a few recent developments.

Instrumentation and data analysis have become more

user friendly than in early days of facilities science.

This has led, among other effects, to a lesser

significance of the instrumentation “gurus” with a

current trend of not including them as the authors of

research papers; the estimate e.g. for biology papers

is that about half of them do not now include any

facility staff members as co-authors (Mesot, 2012).

The advances of instrumentation and Internet

have also led to the emergence of specific services

for research and industry such as the UK National

Crystallography Service (Coles and Gale, 2012) that

allows users to send their samples for remote

investigation according to one of the service plans.

The sample exposure on a large facility like

synchrotron radiation source may be just one of the

experimental techniques included in the service plan

so that users have got a “seamless” interface for the

multi-aspect investigation of a crystal substance

submitted. The service provider then collects all the

experimental data and supplies them to the user in

pre-agreed formats. The facilities themselves have

also started offering this sort of “express” service

with the user presence not required for the conduct

of experiment.

The users’ attitude towards research may also

have a significant influence on the research lifecycle

and services in support of it. The user monitoring

exercise performed by PaNdata initiative showed

that about seven thousand of visitor researchers

across Europe, or 22 per cent of them have used

more than one neutron or synchrotron radiation

facility for their investigations (http://wiki.pan-

data.eu/CountingUsers). The reasons for this

substantial level of facilities sharing are often of a

research nature as the characteristics of the

experimental environment are different between

facilities. The facilities sharing is a strong incentive

for having a common infrastructure for data

management and user management which is now a

focus of PaNdata Open Data Infrastructure project

(see under http://pan-data.eu/).

Another driver for change in data management

and data curation is the emergence of new

experimental techniques like neutron tomography, or

using robots for manipulating multiple samples

exposed to a synchrotron beam, or studies of

dynamics of materials. The new techniques produce

larger volumes of data making Big Data bigger than

ever; they also raise potential opportunities for

researchers to perform comparative and multi-aspect

studies for the same samples using different

experimental techniques, or using the same

experimental technique for much wider variety of

different samples. These trends appeal to providing a

richer, well annotated and linked context for

experimental data across different facilities, different

experimental techniques and different sample types

so that the mentioned research opportunities for

comparative and multi-aspect studies could turn

reality.

2.2 Challenges and Opportunities

The challenge of Big Data in terms of more

processing power and more network bandwidth

required is imminent and well understood. We will

not detail it here apart from to note that addressing

particular parts of the data files and archives for their

inclusion in the research discourse, e.g. citing

granular parts of the immense datasets, requires an

adequate modelling of data, and scalability of data

management.

The change of the instrumentalists’ role who as

we mentioned do not always receive a due credit for

their job of preparing sophisticated experiments

requires re-thinking of the attribution methods for

research papers and other research outputs such as

datasets. Facilities science may look at the

developments such as role-based attribution in other

fields of research (Marcos et al., 2012); this is just

one example of how specialists in the facilities’

information departments could explore the new

information culture elsewhere, and promote the best

practices of it across facilities science. This example

also shows that data curation is in fact a

responsibility of everyone involved in research

lifecycle: the authors themselves, not any curation

unit down the research results distribution road,

should be able to add the structured description of

roles according to a reasonable metadata standard.

Information departments then can be seen as

hubs or centres of expertise which monitor, refine,

DATA2013-2ndInternationalConferenceonDataManagementTechnologiesandApplications

212

and communicate best practices of data curation for

other stakeholders (research papers authors in the

last example). The consistent and clearly formulated

framework will make a collaborative data curation

effort much better defined and communicated, and

the best data curation practices more readily adopted

by the research community. Supervision of various

kinds of information through the research lifecycle

will help then to create rich data aggregations and

reproducible research workflows with contributions

naturally made by different lifecycle stakeholders.

The next challenge and opportunity is presented

by the emergence of research services such as the

aforementioned UK National Crystallography

Service. This trend raises questions on the user

management, research proposals management and

data management in facilities science. Just one

example of that are the future role and the content of

data management policies which some facilities tend

to impose on their users as a pre-condition for

getting a facility resource for research. The policy

may ask users to agree with the public release of

their experimental data after a period of exclusive

access (typically a few years), or contain the

requirement to submit the list of resulting

publications back to the facility user office. This

works well in a traditional business model of

facilities science but does not take into account the

emergence of the service intermediaries who may

need to be a subject of the data management policy,

too, so that it becomes a multilateral agreement.

The data management policy format which is

now just plain text is also questionable as it is not

interpretable without a human; this will be likely not

enough for the automated research proposals

management and data release management across

different facilities. The development of licences for

data re-use, or the adoption of suitable ones could

alleviate the problem but licences might need a

proper machine-oriented modelling for policy

enforcement; the indication of what is possible in

respect to structured modelling and automation of

data licences can be seen in the recent formation of

the Linked Content Coalition

(www.linkedcontentcoalition.org) endorsed by the

European Commission and some national

governments. Again, information departments of

large research facilities might consider borrowing

the advanced practices and models of data licensing

for their re-use in facilities science.

Another important consideration is the

interoperability of metadata models and their actual

implementations for different research facilities. The

idealized metadata model for facilities science that

we call Core Scientific MetaData (CSMD)

(Matthews et al., 2012) is derived from a generic

research lifecycle in facilities science:

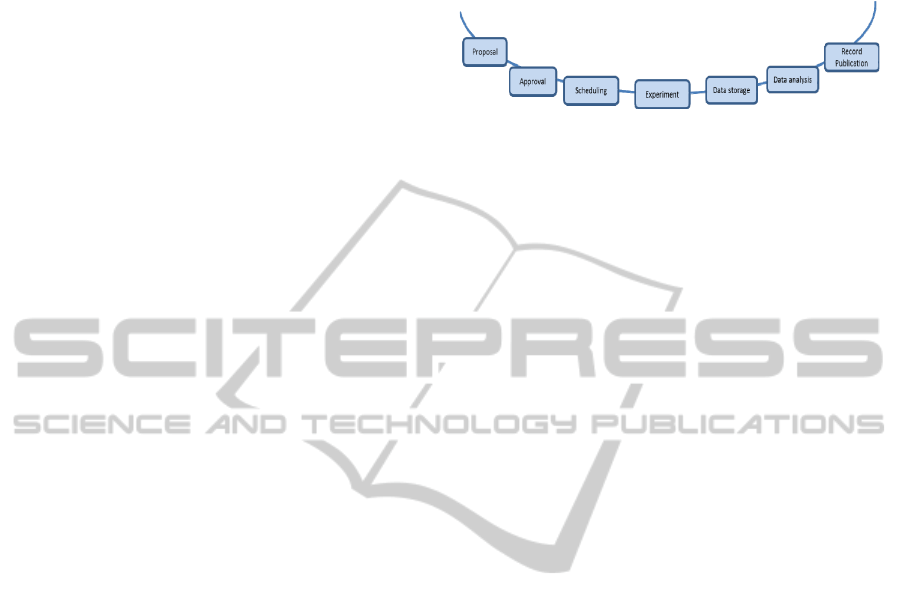

Figure 1: Generic research lifecycle in facilities science.

The different stages of research lifecycle produce

data artefacts (research proposals, user records,

datasets, publications etc.) that are similar across

research facilities so having a common metadata

model like CSMD seems sensible. However, it may

be applied differently by different facilities; there are

a few CSMD implementations in data catalogues

across Europe by virtue of the ICAT platform

(http://code.google.com/p/icatproject/) but the

model, and the actual use of its elements may vary

among implementations. This may result in extra

design and implementation overheads when we

consider federated services for a few facilities (even

when based on the same software platform), also

there is no guarantee that once we have the federated

solution agreed and implemented, it will be not

affected sooner or later by the diverging business

needs of different participants. The common data

curation framework for facilities science might help

to have these needs permanently monitored, properly

communicated and effectively reconciled thus

serving as a well-structured business analysis

wrapper for technology solutions.

An interesting development that may be

considered a part of the emerging data curation

framework but has exposed certain challenges, too,

is the recent effort of minting Digital Object

Identifiers for investigations performed on ISIS

neutron facility (Wilson, 2012). Having permanent

identifiers minted for particular investigations

(experiments) should be enough for linking them to

datasets and publications but in order to have a

structured and linkable representation of a facility

research environment, other parts of it such as

scientific instruments, experimental techniques,

people, organizations, software, derived data sets

etc. need minting or borrowing identifiers for them,

too. There is currently no sustainability model for

this activity, as well as for the steady production and

support of landing Web pages where the permanent

identifiers (all kinds of them) should ideally resolve

into. The different aspects – modelling,

technological, operational – of the permanent

identifiers management should be an important part

DataCurationFrameworkforFacilitiesScience

213

of the data curation framework for facilities science.

We should also mention organizational barriers

to sharing the content and the context of the research

discourse: grant applications, facilities beam time

applications (research proposals), the raw data

collected, the research outputs, the models and the

software used for data analysis or long-term digital

preservation – all these components tend to be

managed and published under separate ownership

but can and should be interlinked and navigable in

order to get the most of the impressive resource

spent on the preparation and the actual conduct of

facilities research. Linked Data might help here, and

it proved to be a productive methodology for

processing Big Data in some important research

fields with industrial output such as drug discovery

(Dumontier and Wild, 2012). There are even more

advanced data modelling techniques for sharing the

reproducible research workflows that are well

accepted in some research domains, e.g. biology

(Bechhofer, 2013). However, these techniques

typically cover only certain parts of the larger

research lifecycle that are immediately related to

research work, with the Researcher as a major target

of data linkage and data sharing. The needs of other

stakeholders residing in education, industry, research

management and funding, or policy making are

underrepresented and do not have a consistent

framework where all of them, along with the

researchers and intermediary services, could fit in.

In the absence of a structured data curation

framework, the information departments of large

facilities are often confined to supplying the

technology solutions and IT services when their next

role could be that of a conscious data curator helping

to increase data value across the entire research data

lifecycle for the variety of stakeholders (Wilson,

2012); information technologies and services would

be then a very important means to underpin the data

curation role but not the end in themselves.

In order to adopt this new role, the information

departments of large research facilities cannot

entirely rely on the existing organizational structure

as their role and actual influence in a larger research

context is inevitably limited. What they can do is

devise and elaborate a common framework for

sharing the existing best practices across different

organizational units and collaborative projects; the

framework will also serve to bring the best practices

from elsewhere for the adaptation to the needs of

facilities science. The projects, initiatives and

working groups that the information departments are

involved in will be a means to support certain

“themes” in the common data curation framework.

This should result in better opportunities for the

organizational units and collaborative projects to

interoperate, to reconcile their priorities, and to set

common (and commonly understandable) goals.

3 COMPONENTS OF DATA

CURATION FRAMEWORK

We consider some aspects of a suitable data curation

framework. It may take into account the actual

content and the stance of the existing frameworks in

the IT-relevant domains such as ITIL for service

management (www.itil-officialsite.com), or the

relevant project management frameworks. Those can

be to a certain extent “role models” of what may

constitute our own framework but there will be

substantial differences, too, owing to the specifics of

facilities science as business environment.

3.1 Data Curation Perspectives

The basis of the aforementioned mature frameworks

is typically two-fold: generalization of best practices

in the field and a consistent conceptual thinking

often represented by the notion of re-usable

“processes” and “functions” that reflect an

importance of the operational perspective in the

business world, and the functional nature of

management style in many business projects and

services. The framework for the research data

curation should include the operational perspective

and may develop a functional approach for certain

domains, too, OAIS reference model for digital

preservation (OAIS, 2012) being a good example of

it. However, owing to the cooperative nature of

scientific research (compared to the more direct

governance in business world) and to the need for

such a framework to be adaptive and comprehensive

enough, it should include more perspectives:

Business Analysis Perspective

The business case for data curation should be

well formulated and permanently updated

Modelling Perspective

Modelling may be applied to a variety of

artefacts: to data or metadata, or to the policies

and business processes

Technology Perspective

Technology is important and should be

consciously harnessed for data curation

Operation Perspective

Data curator should always keep in mind the

operational environment and issues that may

DATA2013-2ndInternationalConferenceonDataManagementTechnologiesandApplications

214

arise in it: scalability, sustainability etc.

Communication Perspective

Structured communication with various data

curation stakeholders should be a permanent

activity accompanying all the others.

3.2 Data Curation Themes

The outlined Perspectives allow considering all the

important aspects of a data curation problem or a

data curation solution; in addition to them, the

adaptive data curation framework will benefit from

having permanent Themes. One or more Themes

may be relevant to the scope of a particular project

or initiative hence they are the tool for mapping the

actual data curation effort (including development of

new approaches and techniques) to the rest of the

framework.

We list the Themes that are deemed important

according to our own experience in data curation

projects; as the framework evolves, they should be

refined through discussions with a variety of

stakeholders across different research facilities:

Table 1: Data curation themes.

Theme Comment

Identification of the

existing and emerging data

curation stakeholders

Also monitoring their needs

that may lead to the roles

change

Facility user management

practices and policies

Including comparative

studies across facilities

Data curation practices and

policies in facilities science

Analysing them for

different stages of facilities

research lifecycle

Data curation practices and

policies elsewhere

To adopt the best of them

in the facilities science

Permanent identifiers * Minting or re-using them

for instruments, techniques,

samples, papers, datasets

etc.

Data Context * Modelling and managing

various metadata and

Linked Data; monitoring

linkable data sources and

services

Data mining * Discovering data patterns;

data indexing and

classification

Data analysis and

visualization *

Including those in

collaborative environment

(“virtual labs”)

Data value and data cost How to model, measure,

and manage them

Standards and

recommendations

Adoption of the best and

opportunities to contribute

Star marked items may be considered particular

techniques of data curation but we reserved

dedicated Themes placeholders for them to

emphasize their importance.

Some of the Themes may look specific to certain

Perspectives but in fact, every Theme may require

many Perspectives applied. As an example, when we

consider minting DOIs we should employ the

Operation Perspective that will advise on the

feasibility and costs of exploiting the practice in a

sustainable manner, and the Communication

Perspective in order to educate stakeholders

concerned, and to get their feedback for the practice

improvement.

3.3 The Framework Application

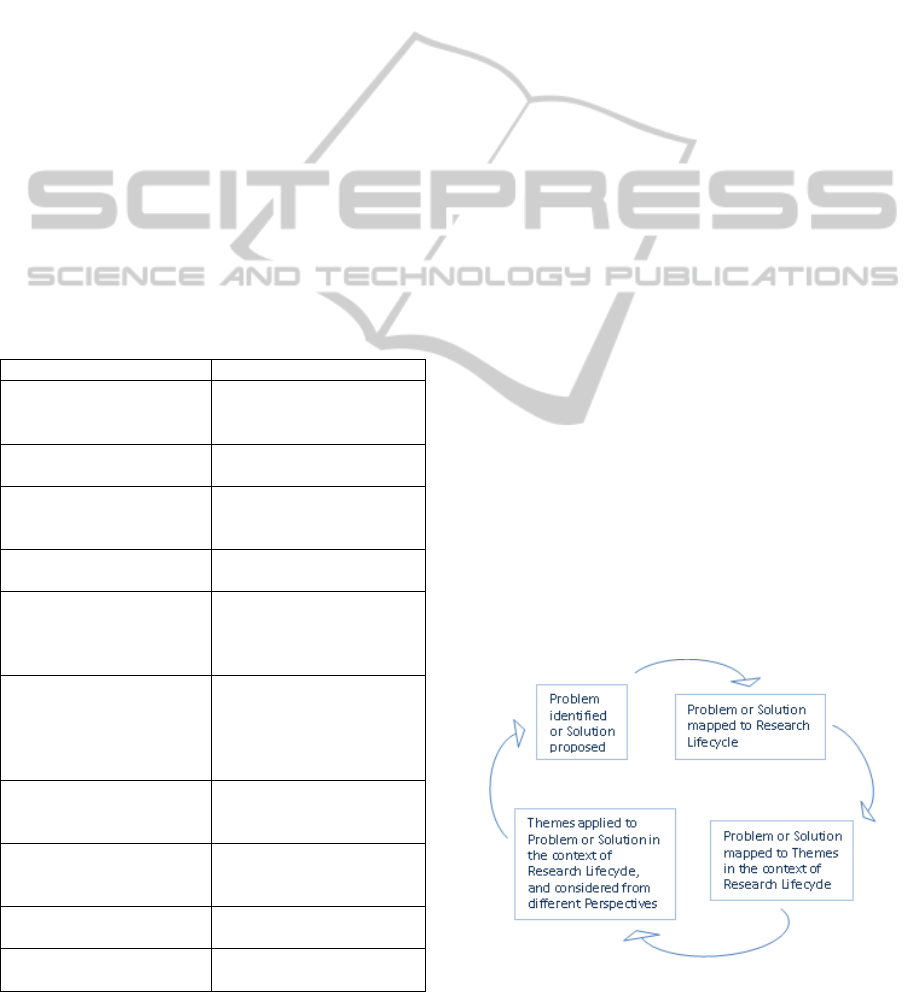

The framework can be applied to the identified

Problems, or to Solutions in order to evaluate their

feasibility or quality. The recommended process can

be outlined as follows:

1) For a particular project aimed at management

or curation of facility science data, identify major

Problems or Solutions that seem viable.

2) Identify where the Problem or the Solution

applies in the facilities research lifecycle (see Figure

1); it may be one or a few stages.

3) Apply different Themes to the Problem or the

Solution, and decide which ones are most relevant or

most important in a particular case (prioritize

Themes for each Problem or Solution).

4) Consider each prioritized Theme from each of

the five Perspectives; decide which Perspectives are

most relevant or most important in a particular case.

5) Elaborate the prioritized Themes and

Perspectives against the Problem or Solution. If new

Problems or Solutions emerge whilst applying the

framework, apply it to them, too.

Figure 2: Data curation framework application.

DataCurationFrameworkforFacilitiesScience

215

As applying the framework will take into account

the significance of Themes and Perspectives in each

particular case, we expect that the entire number of

aspects to be considered (that is a multiplication of

the number of significant Themes by the number of

significant Perspectives) should not exceed a dozen

or so for a particular Problem or Solution. If this

reasonable limit is going to be exceeded, the

Problem or Solution should be decomposed, with the

framework applied to the identified components.

Applying the framework stops when all the

Problems or Solutions have been considered from all

significant Perspectives. The examples of particular

outputs resulted from the framework application will

be the IT solution quality assessment, or the data

management plan.

3.4 Further Works and Reference

Implementation

The core of the framework outlined in this paper

should be discussed with a variety of data curation

stakeholders in different research facilities, and

elaborated accordingly; PanData consortium and its

projects (www.pan-data.eu) will be a proper forum

for that. The resulted framework can be applied then

to a particular business case in the interests of a

certain research facility, or a few.

The case we are willing to consider is the long-

term digital preservation of the research outputs of

neutron and photon facilities; specifically, the

preservation of the more complex information

aggregations than just raw datasets. This will require

a more universal and multi-aspect approach than can

be found in particular digital preservation projects

that typically have their own specific agenda and use

the data samples of facilities research output only for

illustration purposes. One of the problems that as we

hope the framework will help to address in digital

preservation is the validated alignment of the system

architecture and technology to the actual data

preservation policies and procedures.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Large experimental facilities have a unique position

in the research landscape that allow them to evolve

from supplying the crude services (time slots and

experimental environment) through various modes

of managing research data to becoming the

researchers’ partners in meaningful data curation.

Sharing and refining the best practices across

organizational units and research centres should

result in birth and growth of a common data curation

framework for facilities science that covers the

entirety of the research lifecycle and takes into

account the business analysis, modelling,

technological, operational, and communication

perspectives. Such a framework will give a common

language for various case studies, system design and

implementation effort of different organizational

units and collaborative projects; it will be therefore a

valuable aid to the consistent and sustainable data

curation in large experimental facilities and

collaborations of them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is related to the projects of PaNdata

collaboration (www.pan-data.eu) supported by the

EU 7

th

Framework Programme for Research and

Technological Development. The authors would like

to thank their colleagues in PaNdata for their input

for this paper although the views expressed are the

views of the authors and not necessarily of the

collaboration.

REFERENCES

Bechhofer, S. et al., 2013. Why linked data is not enough

for scientists. Future Generation Computer Systems,

2013, 29(2), 599-611.

Coles, S. J. and Gale, P. A., 2012. Changing and

Challenging Times for Service Crystallography.

Chemical Science, 2012, 3 (3), 683-689.

Dumontier, M. and Wild, D., 2012. Linked Data in Drug

Discovery. IEEE Internet Computing, 2012, 16(6), 68-

71.

Matthews, B. et al., 2012. Model of the data continuum in

Photon and Neutron Facilities. PaNdata ODI,

Deliverable D6.1. http://pan-data.eu/sites/pan-

data.eu/files/PaNdataODI-D6.1.pdf.

Marcos, E. et al., 2012. Author order: what science can

learn from the arts. Communications of the ACM,

2012, 55(9),39-41.

Mesot, J., 2012. A need to rethink the business model of

user labs? Neutron News, 2012, 23 (4), 2-3.

OAIS, 2012. Reference Model for an Open Archival

Information System. CCSDS 650.0-M-2 (Magenta

Book) Issue 2, June 2012. http://public.ccsds.org/

publications/archive/650x0m2.pdf.

Wilson, M., 2012. Meeting a scientific facility provider's

duty to maximise the value of data. In DataCite

Summer Meeting, Digital Research Data in Practice

(DataCite2012), Copenhagen, Denmark. http://

epubs.stfc.ac.uk/work-details?w=62852.

DATA2013-2ndInternationalConferenceonDataManagementTechnologiesandApplications

216