TOWARDS INTEGRATING TECHNOLOGY SUPPORTED

PEER-TO-PEER ASSESSMENTS

INTO MATHEMATICS EDUCATION

Experiences with iPad Mobile Tablet Technology

Ghislain Maurice Norbert Isabwe

1

, Frank Reichert

2

and Svein Olav Nyberg

2

1

Department of ICT, University of Agder, Jon Lilletuns vei 9, Grimstad, Norway

2

Faculty of Engineering and Science, University of Agder, Jon Lilletuns vei 9, Grimstad, Norway

Keywords:

Peer-assessment, Mobile Technology, Formative Assessment.

Abstract:

This paper addresses technology supported formative assessment in university mathematics education. The

challenges of formative assessment are the requirements for regular feedback and more student engagement in

the learning process. This paper suggests integrating peer-to-peer assessment in mathematics education, using

mobile tablet technology. The students are engaged in providing feedback to each other and the technology

allows for fast and regular feedback provision. The paper presents the results of experiments with undergradu-

ate engineering students, using iPad tablets and a learning management system. It is shown that mobile tablet

technology can greatly contribute to the integration of peer-to-peer assessment into mathematics education;

and providing peer-feedback is a practical approach to formative assessment.

1 INTRODUCTION

The new media technologies have not only extended

learning opportunities, but they are also reshaping the

university education as a whole. The ever increasing

number of students and the quest for excellence in ed-

ucation, are also driving research efforts into new ped-

agogical models, which would be appropriate in this

media-rich world. For instance, all undergraduate en-

gineering students must study mathematics courses;

and they may be grouped into larger classes with a

minimum of teacher-to-student interaction (this is a

real concern at the University of Agder and other uni-

versities around the globe). Technologies such as

real-time video streaming are being used for teach-

ing, but there is still a challenge to assess the students’

progress as they learn (formative assessment).

The main purpose of this study is to investigate the

students’ attitudes towards technology enabled peer-

to-peer assessment (P2PASS) using iPad tablet com-

puters. P2PASS is a form of formative assessment,

expected to have a positive impact on the students’

learning performance as well as their reflective skills.

Peer assessment encourages active learning and col-

laboration among students, as they assess each other’s

work and provide constructive feedback. On the other

hand, this study will provide empirical data on the us-

ability of the adopted mobile technology and the fea-

sibility of P2PASS in a mathematics course.

The study will address the following research

questions:

• What are the benefits that students can get from

involvement into a P2PASS in mathematics edu-

cation at university level?

• What are the challenges and opportunities for in-

tegrating mobile technology enabled P2PASS in

mathematics education at university level?

The authors argue that mobile tablet technology

offers many advantages for learning: students can ex-

perience a natural feel with finger writing or stylus

in the same way as pen and paper; this would fos-

ter a faster technology adoption. Once the students

get used to this technology, it can also be time saving

compared to using alternative equation editor tools

such as MathML (Mathematics Markup Language),

which requires a substantial amount of time to input

mathematical symbols. There is also a lack of flexibil-

ity in automated systems for the student to show his

own approach to problem solving. Grading systems

rely mostly on multiple choice questions (MCQ) type,

hence missing the possibility to assess the student’s

119

Maurice Norbert Isabwe G., Reichert F. and Olav Nyberg S..

TOWARDS INTEGRATING TECHNOLOGY SUPPORTED PEER-TO-PEER ASSESSMENTS INTO MATHEMATICS EDUCATION - Experiences with

iPad Mobile Tablet Technology.

DOI: 10.5220/0003919301190125

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2012), pages 119-125

ISBN: 978-989-8565-07-5

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

understanding, strategies, reasoning, procedures and

communication because those aspects cannot simply

be reflected in the final answer. Moreover, peer-

assessment on tablet technology adds a great advan-

tage to be able to provide feedback on the same sheet

as the assignment itself (student’s work). The re-

mainder of this paper is organised into 4 sections.

In Section 2, this paper provides a brief overview

of peer-assessment, including technology supported

peer-assessment systems. In Section 3, the methods

for this study are presented and in Section 4, the re-

sults of the experimental work are presented together

with analysis. The final part, Section 5, summarizes

our conclusions and future directions.

2 RELATED WORK

Peer-to-peer assessment stems from the practice of

active learning. Falchikov (2003) emphasised the im-

portance of students’ involvement in the assessment

process not only as the “testees” but also as the asses-

sors. The author suggested that students could be in-

volved more productively in their assessment by peer

assessment. In peer assessment, students rate the per-

formance of their peers through a four-stage process

comprising the preparation, the implementation, the

follow-up and evaluation as well as the replication.

Despite peer-assessment being an “excellent way of

enhancing the learning process”, it may have some is-

sues such as the students’ lack of confidence and ca-

pacity to assess fairly and accurately, and their unwill-

ingness to do the teacher’s job among other things.

In recent studies on technology-supported peer

assessment systems (Wen et al., 2008; Al-Smadi

et al.,2010; Chen, 2010; de-Marcos et al., 2010), sev-

eral advantages were reported, from the savings in

time and costs to improved students’ performance.

Web-based peer-assessment systems allow the asses-

sors (students and teachers) to enter grades and feed-

back. The systems described may be efficient for sub-

jects such as history, language studies and other stud-

ies for which students are assessed on oral presen-

tations or plain text answers. The authors have not

reported on any tools for writing mathematical sym-

bols and equations. In addition to that, there are no

indications of how the assessors could clearly indi-

cate on the same sheet any missing points and pro-

vide easy access to feedback. It is noted that mo-

bile technology has also been considered for peer-

assessment (Chen, 2010; de-Marcos et al., 2010),

but in both studies there was no consideration for a

touch input interface. A separate study at the Uni-

versity of Southern Queensland (Brodie et al., 2009)

considered the courses where standardized answers

and feedback could not be generated, thus requiring

a marker’s feedback on the individual level. Such

courses involve a lot of mathematical or technical

drawings, which proved to be time consuming for stu-

dents to produce feedback. In that work, they studied

the online marking with typed comments (there were

text boxes used for adding comments on each assess-

ment criteria) and a second option to provide hand

written annotations on the students’ assignments us-

ing a Tablet PC (Toshiba Portege M750). At the end,

the marker in this experiment was “supportive of the

use of the Tablet PC”. The analysis done thereafter

showed no significant difference in the quantity and

the quality of feedback, but still the handwritten feed-

back provided more details. Besides special tools that

are needed for assessing mathematics, there is also a

need for appropriate mathematics assessment rubric

to help students objectively assess their peers’ work.

Egodawatte (2010) proposed a comprehensive rubric

for assessing mathematical problem solving tasks.

3 METHODS

Subsequent to a literature review, an experimentalist

approach was adopted for conducting user studies and

technology evaluation. The investigations consisted

of experiments, observations and a survey which was

completed at the end of the experiments. To study

the integration of P2PASS into mathematics educa-

tion, the researcher obtained consent from the teach-

ing staff of first year and second year engineering

mathematics to use the exercises from their respective

courses. This has allowed the study on the assess-

ment of learning while it is happening. The teachers

provided both the question papers as well as the cor-

rect answers, the latter being needed for the students

to provide correct and meaningful feedback to each

other.

3.1 Research Intentions

The practice of peer assessment has been around for

several years and in different fields of study. However,

to the best of our knowledge, still a lot has to be done

in the area of mathematics peer-assessment based on

mobile tablet technology. Therefore, this study in-

tends to help understand this topic from a practical

point of view:

1. Can students perform the peer assessment in

mathematics using mobile technology tools and

the LMS?

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

120

2. How do students actually perform the involved

tasks (solving mathematics problems, providing

and receiving feedback)? Which usability prob-

lems that the students may find?

3. How is the student peer-feedback? Questions re-

lated to the quantity, quality and clarity of the

peer-feedback

3.2 Participants Sample

The participants in this study are engineering students

in: mechatronics, as well as civil, computing, elec-

trical and electronics engineering. All participants

were taking a mathematics course at the time of ex-

periments and, they had basic computer literacy with-

out prior experience of using iPad tablets. There were

96% (23)male and 4% (1) female students. 63% of the

participants were between 20-25 years old, whereas

17% (4) were below 20 years and the remaininng

were above 25 years old including 13% (3) older than

30 years. With a total of 24 respondents, the study

would uncover usability problems to a great extent. In

fact, previous studies (Nielsen and Landauer, 1993)

(Nielsen, 1994) suggest that as few as 5 users are

good enough for simple user testing (qualitative stud-

ies) and 20 users can typically provide a reasonable

confidence interval in quantitative studies.

The experiments were conducted during the au-

tumn semester 2011. This paper reports on the

researchers’ observations, the participants’ opinions

collected through a think-aloud technique and the re-

sults of a survey instrument.

3.3 Systems and Technologies

This study was based on the use of Apple iPad tablet

computers with a selection of mobile applications for

the iOS operating system. The iPad was chosen as

a mobile platform to take advantage of the mobility,

portability, wireless connectivity, relatively high pro-

cessing power as well as a large memory. Addition-

ally, the iPad has a good support for multimodal user

interfaces including the support for hand-writing. The

iPad touch screen is of a great interest because it is

possible to directly write on it, especially the math-

ematics which involve a lot of symbol characters in

equations and formulas. In this work, we used a mo-

bile application to annotate, delete, and input text on

top of PDF documents, using either a finger or a stylus

pen.

It is argued that for a formative assessment to be

effective, the feedback should be timely accessible

to the intended receiver (a student). On the other

hand, however, peer-to-peer assessment also requires

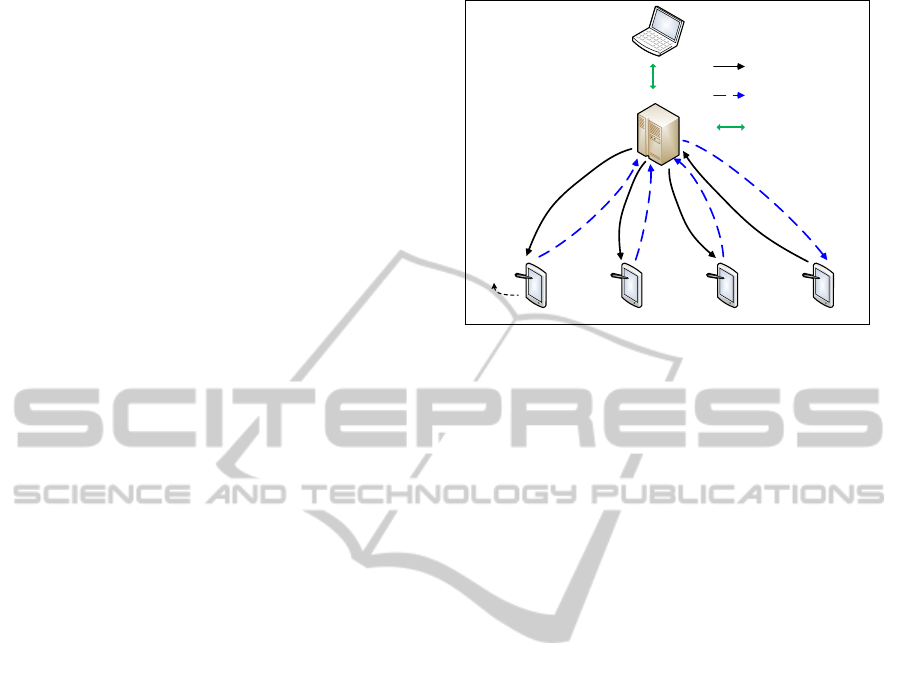

Student A Student B Student C Student D

Feedback on Student D’s

work

Learning Management

System (LMS) Server

Teacher

Student D’s work

Teacher’s moderation on

peer-feedback

C

B

A

{A, B ,C}

DD DD

D

T

a

bl

e

t

c

ompute

r

Figure 1: Peer-to-peer assessment experimental model.

equal active participation of all students, both as feed-

back providers and feedback receivers. Therefore,

there is a need for a system to allow submission of

the work to be assessed and subsequent access to the

same work for the assessors (feedback providers); es-

pecially in case of a synchronous assessment process.

This was achieved using a Learning management Sys-

tem (LMS) called ‘Fronter’ (Pearson, 2011) and an

iPad web browser application ’iCabMobile’ (Clauss,

2011) which supports downloading and uploading of

files to the LMS. Each participant can have read and

write access rights to documents owned by three other

students so that he/she could assess their work as il-

lustrated in Figure 1. In this way, everyone was able

to provide feedback to up to three other students, and

likewise receive up to three feedback from different

colleagues. It is argued that this can help students to

learn from different perspectives.

3.4 Experiment Design

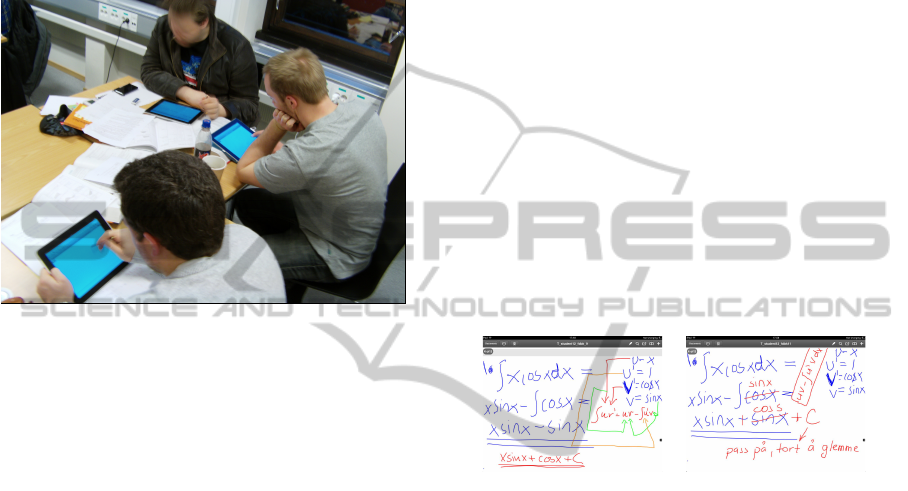

This study was conducted in a controlled environ-

ment, a laboratory setting as shown in Figure 2. Be-

fore the experiments begin, the researcher uploaded

to the LMS a set of mathematics exercises provided

by the teacher. At the start, each student was given an

iPAD, and the researcher explained the peer-to-peer

assessment process for 10 minutes, with a brief demo

of the tools on the iPad. Then students were grouped

according to their performance in the last mathemat-

ics exams, in such a way that each group of 3 students

would have at least one member with either an ”A” or

”B” grade where possible. Collaboration was encour-

aged among group members. Upon completion of the

given exercises, the correct answers were uploaded to

the LMS, and the research explained the mathemat-

ics assessment rubric, which consisted of five crite-

TOWARDSINTEGRATINGTECHNOLOGYSUPPORTEDPEER-TO-PEERASSESSMENTSINTOMATHEMATICS

EDUCATION-ExperienceswithiPadMobileTabletTechnology

121

ria: the Understanding, Strategies, Reasoning, Proce-

dures and Communication. The assessors (students)

were required to rate their peers’ performance (High,

Medium, Low) and provide a feedback. Once all the

papers are marked and uploaded back to the LMS,

each participant should be able to see his/her initially

submitted work along with the feedback.

Figure 2: Peer-to-peer assessment session.

Subsequent to students’ grouping, each partici-

pant solved the given questions using the iPad and

submitted the work to the LMS. Once everyone has

submitted, the correct answer sheet was made acces-

sible to all, and every participant was assigned 2-3 pa-

pers to assess with reference to the assessment rubric.

The next step was to submit the marked papers with

feedback to the LMS so that each participant could

have access to 2 or 3 feedback provided by his/her

colleagues (peers).

A survey instrument was used to collect students’

opinions on peer-to-peer assessment in general, their

experience with mobile technology supported peer-

to-peer assessment system and the way forward (po-

tential improvements).

4 RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

4.1 Summary of the Researcher’s

Observations

At the beginning of all experiments, students ap-

peared very interested in the process and as expected

some of them started exploring the iPad as soon as

they were handed to them. There was a mixture of

curiosity and a great interest in the new experience.

As the researcher explained about the process, stu-

dents were engaged in finding out the available tools

on iPad and within 5-10 min, about 40% of them had

already managed to download the mathematics ques-

tion paper. It was also observed that around 25 % of

the students had a tendency to first solve the prob-

lems on paper then write down the answers on the

iPad. Despite the guidance of the researcher for the

students to work on the touch interface straight away,

still some of them resisted and kept on using both

methods (pen and paper as well as iPad touch inter-

face). 60 to 70 % of the students used the pen at least

on one occasion for solving the math problems, and

one of the respondents just solved all the problems

on paper and the researcher helped to scan the pa-

per (using the iPad camera) and uploaded the paper

as a PDF document on Fronter. On the other hand,

all students were very enthousiastic in providing peer-

feedback using the touch interface. Figure 3(a) and

figure 3(b) illustrate an example of how two students

provided feedback on the same work but in a different

way, with one marker providing an indication of what

was missing and the right formula that should have

been used.

(a) Student ‘A’ receives

feedback from student

‘Y’.

(b) Student ‘A’ receives

feedback from student

‘Z’.

Figure 3: Example of 2 feedback received by one student.

Peer-feedback comprised of both free text as well

as typed text. Even tough an assessment rubric was

given, many students also gave a feedback in their

own words and indicated the errors on the answer

sheet as shown in Figure 4(a). On the other hand,

however, there were also students who used keywords

for the performance levels (Low, Medium, High) to

rate their peers’ work as shown in Figure 4(b). Anno-

tations were observed on a majority of marked paper;

which indicates the willingness of students to provide

a more personalized feedback rather than strictly con-

forming to the assessment rubric. This study showed

indications of promoting student responsibility and

high level of engagement in learning.

Collaboration among students was also stressed

in this study, and students were often seen seeking

help from the peers in their group as well as those

in the neighbouring group. Timely help was offered

as the researcher observed the students explaining the

math principles and referring their peers to the rele-

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

122

(a) Detailed feedback. (b) Summary feedback.

Figure 4: Peer-feedback provision.

vant course materials from their mathematics books.

From the usability perspective, all participants

were generally challenged by the new tools and

needed assistance from the researcher, in addition to

the instructions sheet that was handed to them at the

beginning. The user interfaces were not very intu-

itive, therefore there was a higher necessity to recall

rather than recognise, which usually minimise mem-

ory loading on behalf of the user. System message

boxes such as ”Open In” or ”Save in Downloads”

don’t tell much the user unless he/she is quite famil-

iar with the interface. The learnability of the tools

proved difficult. The affordance of the PDF Expert

application was liked by the majority of users because

they could easily manage to choose the tools needed

for opening a file, writing and saving; but scrolling

and clicking was not obvious since the system respon-

siveness was not always the same. Students adopted

a trial and error approach to achieve their goals. The

students appeared to have the pleasure with the iPad,

and the portability of the device was well appreciated

with some users sitting in a very relaxing way while

working on the given task.

4.2 Survey Results

4.2.1 Students’ Opinions on P2PASS

In a previous study related to student peer-assessment

(Isabwe et al., 2011), we have found that students

would be interested in getting feedback from their

peers. The survey results in this study confirmed a

positive attitude towards peer-assessment, with only

8% of the participants below the average on the Lik-

ert scale as shown in Figure 5(a). The majority of

the respondents (67%) believe that their colleagues

can provide them with a meaningful and fair feed-

back. In addition to that, 50% of the respondents felt

confident to make a fair and responsible assessment

of their peers’ work and 25% were not sure, whereas

25% of the respondents said ’no’. Upon completion

of the peer to peer assessment exercise, 21% and 38%

found the peer feedback ’very useful’ and ’useful’ re-

spectively.

Stronglydislike 0

28%

13 54%

5 21%

Stronglylike 4 17%

24

0

0%

2

8%

13

54%

5

21%

4

17%

Stronglydislike

Stronglylike

0

2

13

5

4

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Strongly

dislike

Strongly

like

No.ofrespondents

(54%)

(

8%

)

(

21%

)

(

17

%)

(a) P2PA rating scale.

Notuseful 0

3 13%

7 29%

9 38%

Veryuseful 5 21%

24

3

12%

7

29%

9

38%

5

21%

Notuseful

Veryuseful

0

3

7

9

5

0

2

4

6

8

10

Not

useful

Very

useful

No.ofrespondents

(

13%

)

(21%)

(38%)

(29%)

(b) Usefulness of P2PA.

No 6

Notsure 6

Yes 12

6

25%

6

25%

12

50%

No

Notsure

Yes

(c) Confident to pro-

vide feedback.

3

12%

5

21%

16

67%

No

Notsure

Yes

(d) Trust to receive

fair feedback.

Figure 5: Students’ opinions on P2PASS process.

The participants also mentioned the usefulness of

peer-feedback provision, with statements such as “it

could help me understand if i did see what other peo-

ple do”, “getting to see common errors would be use-

ful for me too” and “when I have to explain some-

thing to another person I do understand it better my-

self”. Peer-feedback provision also helps in reflective

skills development as one student pointed out: “Help-

ing others to understand is an easy way of forcing my-

self to reflect on my own competence”. Other students

were interested in peer-feedback because they be-

lieve that peer-feedback on assignments greatly helps

a student’s progress in his/ her learning process. The

study suggests that 20-40 minutes could be spent on

feedback provision regularly (at least once every two

weeks).

On the other hand however, solving the mathemat-

ics problems on iPad appeared time consuming for the

participants since it was their first time using this tool.

The user interfaces were not user friendly, and one of

the student expressed his frustration saying that ‘A lot

of time was wasted due to problems with the inter-

face, and way too much time spent trying to solve the

math problems compared to giving feedback’. Giv-

ing feedback was a lot easier, at first much of the time

was spent on navigating the iPad rather than provid-

ing feedback, but this trend decreased as students got

TOWARDSINTEGRATINGTECHNOLOGYSUPPORTEDPEER-TO-PEERASSESSMENTSINTOMATHEMATICS

EDUCATION-ExperienceswithiPadMobileTabletTechnology

123

used to the interface.

0

2

11

9

2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Stronglydissatisfied Stronglysatisfied

No.ofrepondents

(

8%

)

(8%)

(38%)

(46%)

(a) Satisfaction with the set-

ting for P2PA.

2

4

7

10

1

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Very

difficult

Very

easy

No.ofrespondents

(

8%

)

(4%)

(42%)

(29%)

(17%)

(b) Difficulty to provide

peer-feedback.

Figure 6: Opinions on P2PA model.

The students expressed mixed opinions on the

mathematic assessment rubric that was given to them.

Some thought it was good and well defined, but oth-

ers could not well understand the criteria. It was sug-

gested that ‘the main focus should be on giving a

written comment instead of giving a mark for each

separate criteria’. There is a clear indication that stu-

dents need more skills to act as assessors. The peer-

feedback was found helpful by 66.6% (16) of the par-

ticipants, the reasons being the opportunity to under-

stand and correct their own mistakes, in addition to

increasing their confidence to perform the given tasks.

Some of the students (high-performer) noted that they

could recognise their mistakes themselves by seeing

the correct answersheet, but others didn’t read the

feedback because they were exhausted by the end of

the experiment. P2PASS has also a motivational fac-

tor among other things. The students mentioned that

the idea of peer-feedback made them spend more time

on their studies and work harder. There is also a ’feel

good and positive competition’ element because stu-

dents can help others and see “how well others have

done and then compare them to oneself”.

Student collaboration was another aspect of study

in this paper. Students worked in groups of 3 stu-

dents, and at the end of the experiment, it became

clear that it was important for them to work together.

A student stated that “Collaboration makes partici-

pants work as a team and discuss ideas. This in turn

increases the knowledge of participants”. The results

here obtained, emphasise the need to foster collabo-

ration among students since it helps them not only for

knowledge acquisition but also for developing their

social skills.

4.2.2 Students’ Opinions on the Usability of

Technology-supported P2PASS

Generally, the system suitability for learning scored

low. Users found difficult to learn the system func-

tionalities, hence conformity with user expectation

was also low. Since the learnability was low for the

majority of users, the effectiveness was greatly af-

fected as the experiments took longer than expected

(average duration was 3 hours). Participants ex-

2

8%

5

21%

5

21%

9

37%

3

13%

Verydifficult

Difficult

Moderatelydifficult

Easy

Veryeasy

(a) Difficulty to use the

tools.

5

21%

13

54%

6

25%

Fascinating

Interesting

Annoying

(b) Appearance & re-

sponsiveness.

Figure 7: Opinion on P2PA tools.

pressed usability problems related to the system re-

sponsiveness and interaction, the user interface was

not very intuitive and iOS “apps dependent” file man-

agement system is not user friendly. The user guid-

ance of the mobile applications that were used was

also poor : there were no detailed error messages and

some of the actions were not confirmed upon execu-

tion; hence prompting the users to repeat the same ac-

tion several times. On the other hand, however, there

are also indications of improvements in suitability for

the task as users get used to the system.

Despite some difficulties to use iPad, the con-

cept was much appreciated; with statements such as

“Portability is important. The touch feature of the

iPad is also better than a mouse, since you can draw

and write uncommon sign without a lot of hassle. The

size, weight and battery power is also important” and

“It might help in the sense that you’d be able to check

out feedback and such at any time, any place”.

4.3 Challenges and Potential

Improvements

This study encountered the challenges concerning the

students’ involvement, conceptual understanding of

peer-assessment as well as technology adoption. Stu-

dents did not respond well to the invitations to par-

ticipate in this study. As a recruitment strategy, par-

ticipants were rewarded with the university bookstore

gift cards, and in some cases their participation was

considered instead of a compulsory coursework. Fur-

ther on, peer-assessment concept was new to the stu-

dents and there were concerns regarding the quality of

feedback they might receive from their peers, the ad-

ditional workload involved and the potential impact

on their final grades. As it was mentioned earlier, par-

ticipants were concerned about their lack of necessary

skills in mathematics assessment; hence we suggest

that a system should be put in place to enhance the

students’ judgment capacity and foster the active role

of students as assessors. Peer-feedback is one of the

good approaches to formative assessment, especially

in large classes because it would be very difficult for a

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

124

teacher and very costly to provide regular individual

feedback. It is also suggested that students work in

groups in order to foster collaborative learning since

it proved beneficial in this study.

The participants also expressed issues related to

the technology tools used in this study, not only be-

cause they were not familiar with the tools, but also

because the tools were not necessarily designed for

mathematics peer-assessment purposes. The prob-

lems range from file management to finding the right

tools such as the pen colors and sizes. The user con-

trol was limited as well, and in some cases partici-

pants could not easily find their way to perform a de-

sired task or go back from an unwanted function. It

was challenging for participants to recognise and re-

cover from errors, since the users were not timely in-

formed on the system status (success or failure). Im-

provements can focus on training the students on the

available tools while working towards a development

of an integrated tool.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presented results of iPad mobile tablet

technology-supported P2PASS experiments for two

mathematics courses. The study confirmed that peer-

assessment can foster student engagement and re-

sponsibility in their learning. In addition to porta-

bility, connectivity and mobility features of the iPad,

this study has proved the advantages of tablet tech-

nology in writing mathematics expressions, and this

can be time saving especially in providing an elab-

orate (step by step) feedback. However, this study

found no clear evidence of the benefits to use iPAD in

solving math problems. The technology acceptance

was found greatly dependent on how well the peer-

assessment could be planned especially in regards to

students’ training on how to use the tools. Future

research is required to find the effectiveness of the

P2PASS carried out over a period of time. This would

be necessary to exclude the effects of learnability is-

sues and to enable the measurement of the potential

impact on students’ performance. It is also desirable

to carry out the same experiments with students of

a different social and ethnographic background since

collaborative learning could be affected by such pa-

rameters. The iPad is easy to use in general but the

current set of available applications and LMS solu-

tions are not well integrated and prevent an efficient

use for P2PASS. This may change once iPad-like de-

vices are cheaper, more widely spread, and when

more integrated solutions have evolved.

REFERENCES

AL-Smadi, M., Guetl, C., and Kappe, F. (2010). Peer as-

sessment system for modern learning settings: To-

wards a flexible e-assessment system. International

Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET),

5 .

Brodie, L., Loch, B. (2009) Annotations with a Tablet PC

or typed feedback: does it make a difference? In Pro-

ceedings of the 20

th

Australasian Association for En-

gineering Education Conference, (AAEE 2009), Ade-

laide, Australia, pp.765-770.

Chen, C. (2010) The implementation and evaluation of a

mobile self- and peer-assessment system. Computers

and Education, 55, pp.229-236.

Clauss, A. (2011). iCab Mobile - Web Browser. Available

on http://www.icab-mobile.de/. Last accessed: De-

cember 2011.

De-Marcos, L., Hilera, J. R., Barchino, R., Jimenez, L.,

Martines, J. J., Gutierrez, J. A., Gutierrez, J.M., Oton,

S. (2010). An experiment for improving students

performance in secondary and tertiary education by

means of m-learning auto-assessment. Computers and

Education, 55, pp.1069-1079.

Egodawatte, G. (2010) A rubric to self-assess and peer-

assess mathematical problem solving tasks of college

students. Acta Didactica Napocensia, 3(1), pp.75-88.

Falchikov, N. (2003). Involving students in assessment.

Psychology Learning and Teaching, 3(32), pp. 102-

108.

Isabwe, G. M. N., Oysaed, H., and Reichert, F. (2011). On

the Mobile Technology Enabled Peer-Evaluation: A

User Centric Approach. In Proceedings of the 7th An-

nual International Conference on Computing and ICT

Research (ICCIR11), Makerere, Uganda, pp.272-285.

Nielsen, J. and Landauer, T. K. (1993). A mathematical

model of the finding of usability problems. In Pro-

ceedings of ACM INTERCHI’93 Conference, pages

206–213.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Estimating the number of subjects

needed for a thinking aloud test. Int. J. Hum.-Comput.

Stud., 41:385–397.

Pearson Plc (2011). Fronter Learning Management Sys-

tem. Available http://com.fronter.info/. Last accessed

December 2011.

Wen, M. L., and Tsai, C. (2008). Online peer assessment in

an inservice science and mathematics teacher educa-

tion course. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(1), pp.

55-67.

TOWARDSINTEGRATINGTECHNOLOGYSUPPORTEDPEER-TO-PEERASSESSMENTSINTOMATHEMATICS

EDUCATION-ExperienceswithiPadMobileTabletTechnology

125