THINKING SPATIALLY, ACTING COLLABORATIVELY

A GIS-based Health Decision Support System for Improving

the Collaborative Health-planning Practice

Ori Gudes

1, 2

, Virendra Pathak

1

, Elizabeth Kendall

2

and Tan Yigitcanlar

1

1

School of Urban Development, Queensland University of Technology, 2 George Street, Brisbane, Australia

2

Griffith Health Institute, Griffith University, University Drive, Meadowbrook, Australia

Keywords: Spatial health decision support systems, Collaborative health planning, DSS, e-Health.

Abstract: The field of collaborative health planning faces significant challenges due to the lack of effective

information, systems and the absence of a framework to make informed decisions. These challenges have

been magnified by the rise of the healthy cities movement, consequently, there have been more frequent

calls for localised, collaborative and evidence-driven decision-making. Some studies in the past have

reported that the use of decision support systems (DSS) for planning healthy cities may lead to: increase

collaboration between stakeholders and the general public, improve the accuracy and quality of the

decision-making processes and improve the availability of data and information for health decision-makers.

These links have not yet been fully tested and only a handful of studies have evaluated the impact of DSS

on stakeholders, policy-makers and health planners. This study suggests a framework for developing healthy

cities and introduces an online Geographic Information Systems (GIS)-based DSS for improving the

collaborative health planning. It also presents preliminary findings of an ongoing case study conducted in

the Logan-Beaudesert region of Queensland, Australia. These findings highlight the perceptions of decision-

making prior to the implementation of the DSS intervention. Further, the findings help us to understand the

potential role of the DSS to improve collaborative health planning practice

.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, a model of planning known as the

‘Collaborative health planning’ has evolved to

become one of the key foundations of contemporary

health planning. This model is grounded in both

‘communicative planning theory’ and ‘population

health theory’ (Gudes et al. 2010). Growing

evidence from the literature shows that large health

systems seeking to create collaborative health

planning projects face many planning challenges,

including engaging multiple stakeholder groups;

making consensus-based decisions; bringing

evidence into the decision-making processes;

planning in a participatory manner; and exploring

the full spectrum of health determinants based on

diverse sources of information.

For this reason, Northridge et al. (2003) argued

that stronger collaborations were needed between

urban planners, health policy-makers, and

community members to ensure effective planning in

the light of ‘Healthy Cities (WHO, 1999)’ initiative.

It is recognised that evidence-based decision making

is critical to the collaborative planning process and

the evidence-based approach is based on an effective

access to data. It was noted that the smart use of data

and publicly available information on health is

essential to generate informed decision-making

(NHHRC, 2009). Literature has suggested that

increasing and improving access to relevant data

may lead to an improved decision-making processes.

Thus, there is a need to develop a framework for

stakeholders to support them to access relevant data.

Some studies have justified the use of decision

support systems (DSS) in planning for healthy cities

as these systems have been found to improve the

planning process (Cromley & McLafferty 2003).

These systems have been gaining prominence in

recent years and have been described by several

researchers over the last few decades as an efficient

support tool for health planning (Reinke 1972;

Reeves & Coile 1989; Higgs & Gould 2001).

148

Gudes O., Pathak V., Kendall E. and Yigitcanlar T..

THINKING SPATIALLY, ACTING COLLABORATIVELY - A GIS-based Health Decision Support System for Improving the Collaborative Health-planning

Practice .

DOI: 10.5220/0003131101480155

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics (HEALTHINF-2011), pages 148-155

ISBN: 978-989-8425-34-8

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

However, knowledge about the impact of DSS on

health planners is relatively limited. This study

provides a framework for organising and delivering

information to planners to use in developing healthy

cities. It also introduces an online Geographic

Information Systems (GIS)-based DSS, developed

for improving the collaborative health planning. To

ascertain whether the DSS has a valuable impact on

health planners, a study is currently being conducted

in the Logan-Beaudesert Health Coalition (LBHC).

This paper provides an overview of the healthy cities

movement and collaborative health planning,

introduces ICT and E-Health approaches and the

DSS. It then discusses a proposed framework for

organising information that can contribute to

collaborative health planning. Preliminary results are

presented to demonstrate the perceptions of

decision-making within the LBHC and the potential

role of the DSS.

2 THE HEALTHY CITIES

& COLLABORATIVE HEALTH

PLANNING

The ‘Healthy Cities’ initiative was officially

introduced in 1986 by Ilona Kickbusch at a

conference of the World Health Organisation

(WHO) in Copenhagen, Denmark. To date, “about

90 cities are members of the WHO European

Healthy Cities Network, and 30 national Healthy

Cities networks across the WHO European Region

have more than 1400 cities and towns as

members”(WHO, 2010). Also, according to Health

Cities Illawarra

(2010), “since 1985 over 3000

healthy cities, towns, villages and islands have been

established throughout the world”. In order to plan

effectively for healthy cities, the historic

collaboration between urban planning and public

health professionals must be revived, and this

collaboration must be based on informed evidence-

based decision-making (Northridge et al., 2003).

However, evidence-based decision-making has been

hindered by the fact that there are no models to

define the type of information that must be

considered by health planners and there is no

method for sharing this information in a meaningful

form. As Flynn (1996) concluded, every community

is unique, with different physical, social, political

and cultural contexts that must be understood in the

planning process. Therefore, it is necessary for

planners to develop a thorough understanding of

each individual community health profile and its

features that influence health. Schulz and Northridge

(2004) developed a public health framework for

health impact assessments. This framework

summarises the different levels of factors that impact

upon health and, therefore, should be considered in

health planning. According to Northridge et al.

(2003), factors that contribute to health can be

divided into four levels, namely: Macro, Meso,

Micro and Individual. According to the model, these

factors interact to contribute to health in the

community, so must all be considered when

undertaking health planning.

Some evidence in the literature supports the

application of collaborative health planning within

the healthy cities approach. First, and broadly,

collaborative planning promotes democratic

decision-making that facilitates shared ownership

and engagement in solutions (Murray 2006). Murray

has also suggested a model to evaluate the level of

collaboration in planning. The model identifies

different levels of collaboration (i.e. Networking,

Cooperation, Coordination, Coalition and

Collaboration) that might be applied. Additionally,

he highlighted the following domains of decision-

making that define collaborative health planning:

Evidence-based decision-making; Perceived

consensus; Participation in decision-making; and

Perceived satisfaction of decision-making. Second, it

encourages planners to communicate, interact and

negotiate with other sectors in order to resolve

disputes between groups that may have some

investment in the planning process (Campbell &

Fainstein 1996). Third, it facilitates a more

collaborative form of governance which in turn

implies a more collaborative and efficient delivery

of services to the community(Bishop & Davis 2001).

Therefore, collaborative health planning has the

potential to become a fundamental approach to

planning.

3 ICT AND E-HEALTH

APPROACHES

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines E-

health as ‘the cost-effective and secure use of

information and communications technologies in

support of health-related fields, including health-

care services, health surveillance, health literature,

and health education, knowledge and research’. The

literature has highlighted the benefits of using E-

health and ICT tools to obtain better understanding

of health planning for policy-makers. Amongst these

THINKING SPATIALLY, ACTING COLLABORATIVELY - A GIS-based Health Decision Support System for

Improving the Collaborative Health-planning Practice

149

some prospective benefits are: increased access to

healthcare services and health-related information,

improved ability to diagnose and track diseases,

more actionable public health information and

expanded access to ongoing medical education and

training for health practitioners (Wave, 2009).

The

National Electronic Decision Support Taskforce (2008)

has also emphasised that EDSS (Electronic DSS) are

essential components of designing a national e-

health strategy.

Conversely, only little research has been focused

on the potential of E-health environments and ICT

tools to alleviate the negative health consequences of

social determinants of health (Han et al., 2010). As

the awareness to the importance of broad

understanding of social determinants of health

grows, it would be crucial to evaluate the impact of

ICT tools and E-health initiatives leveraging health

planners and decision-makers knowledge. Thus, ICT

tools and E-health initiatives should be focused on

finding innovative ways to enhance the day-to-day

work efficiency of health planners.

One of the innovative ways to present, store,

analyse and manipulate information is by adding its

spatial aspect. Particularly, given that social

determinants of health are spatially oriented. In this

regard, E-health initiatives may provide new

standards of accessibility to spatial health data. For

instance, health information could be geocoded and

displayed spatially, so end-users can create maps by

using different layers of spatial information overlaid

each other. Further, spatial analysis can be applied

by mapping layers of socio-economics,

demographics, and projected regional growth

forecasts, thus providing a new way of looking at

health concerns. Thus, application of spatial

technologies is an important step towards a better

understanding of public health issues and their

inherent complexities and for gaining insight into the

spatial distribution of health determinants (Higgs &

Gould, 2001). However, it is essential to expand the

use of this tool through online ICT platforms or as

part of broader E-health initiatives, to support health

decision-making processes.

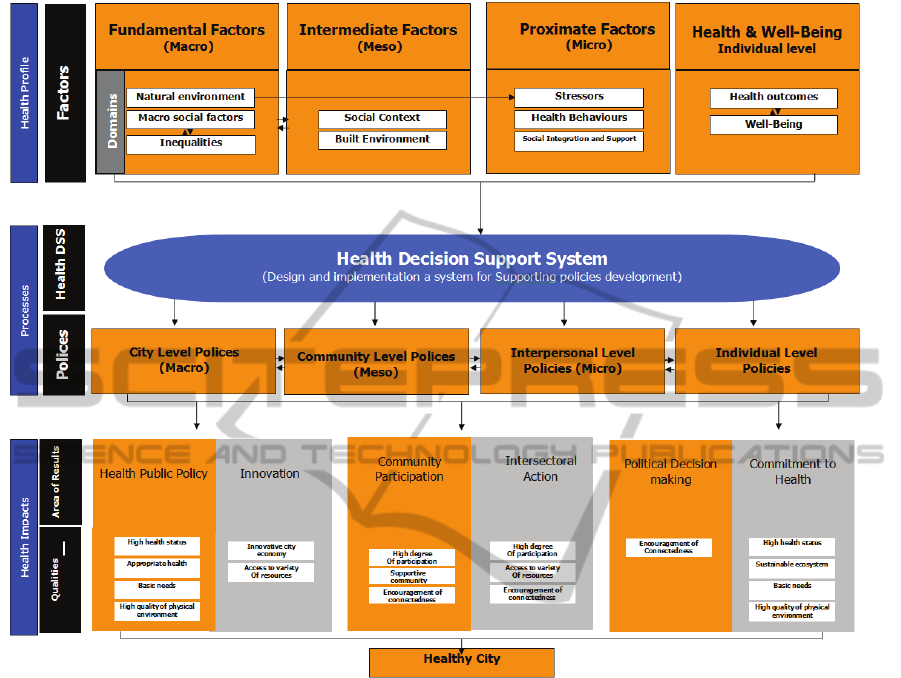

4 A FRAMEWORK

FOR COLLABORATIVE

HEALTH-PLANNING

The overall aim of decision support systems (DSS),

without substituting decision-makers, is to improve

the efficiency of the decisions made by stakeholders,

optimising their overall performance and minimising

judgemental biases (Turban 1993). A framework has

been proposed for collaborative health planning that

illustrates the overall place of DSS within a healthy

cities’ planning initiative (See Appendix). However,

it is imperative that the DSS be based on a broad

information framework. Specifically, it is suggested

that the Information Management Framework based

on Schulz and Northridge (2004) should guide the

development of a community health profile, with

information being derived from multiple sources.

The ability to present this information in

meaningful, accessible and usable ways is a critical

challenge for establishing healthy cities. In this

regard, Duhl and Sanchez (1999) defined a list of six

fundamental characteristics (Health public policy,

Innovation, Community participation, Intersectoral

action, Policy decision making and Commitment to

health) that would be needed to create a healthy city.

If these characteristics are adopted, it is likely that a

healthy city will emerge. Thus, this framework

suggests that by utilising a DSS as part of a broader

healthy cities planning process, it is more likely that

healthy community will be established.

One of the innovative ways to present, store,

analyse and manipulate information for local

decision-making is by adding a spatial aspect,

particularly given that social determinants of health

are spatially oriented (i.e., grounded in place). In this

regard, health information could be geo-coded (into

Geographical Information Systems [GIS] software)

and displayed spatially, so end-users can create

maps by using different layers of spatial information

overlaid on each other. This method provides a new

way of looking at health concerns and may lead to

new decision-making. Thus, application of spatial

technologies is an important step towards a better

understanding of public health issues and their

inherent complexities and for gaining insight into the

spatial distribution of health determinants (Higgs &

Gould, 2001). However, it is essential to expand the

use of this tool through online platforms or as part of

broader e-health initiatives.

For example, for decision-makers to identify

gaps in the provision of health facilities in a given

community, GIS could be utilised to examine the

effect of travel time to health facilities by mapping

catchment areas and travel zones. The impact of new

facilities or new transport routes can be examined in

hypothetical scenarios. By placing this information

in an online setting, the capacity to share

information in a variety of forms will improve

stakeholders’ involvement in decision-making,

horizontal knowledge sharing and simplicity of the

HEALTHINF 2011 - International Conference on Health Informatics

150

decision process (Dur, Yigitcanlar & Bunker 2009).

Testing this framework in a real case-study would

ascertain whether the DSS has a valuable impact on

health planners.

5 CASE STUDY:

THE LOGAN-BEAUDESERT

HEALTH COALITION

The Logan Beaudesert Health Coalition (LBHC) is a

partnership established to address the growing level

of chronic disease in the region. The initiative

intended to build on work that had preceded it,

enhancing existing services and infrastructure,

establishing formal partnerships and mechanisms to

improve the coordination of existing resources as

well as planning for additional services and

strategies. It was initiated with a view to improving

health capacity at multiple levels through improved

and responsive localised planning. The Coalition has

a central board committee which oversees six health

initiatives or working groups, each focusing on a

specific area identified as needing attention. These

working groups focus on the early years of life (0 to

8 years), multicultural health, prevention and

management of existing chronic disease, integration

between general practice and acute settings, efficient

management and transfer of health information and

health promotion. Each group has a leader or project

manager

and a selected group of key stakeholders

from multiple sectors or relevant organisations. The

working groups are responsible for facilitating

decisions, polices or strategies by providing

recommendations and information to the LBHC

board. The LBHC board coordinates and directs the

coalition as a ‘whole’. Thus, given its focus on

collaborative decision-making, the LBHC is an ideal

platform from which to develop and observe the

DSS and its potential role.

6 METHOD

The purpose of this study was to understand the

potential role of the DSS in improving the

collaborative health planning practice of the LBHC.

Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected

prior to the implementation of the DSS to explore

the decision-making strategies and experiences of

the coalition members. The quantitative data was

collected using a 31-item survey based on several

decision-making scales (Dean & Sharfman, 1993;

Flood et al, 2000; Bennet et al, 2010; Parnell & Bell,

1994). The items measured the following four

dimensions of decision-making outlined by Murray

(2006): Evidence-based decision-making (5 items);

Perceived consensus (4 items); Participation in

decision-making (3 items) and Perceived satisfaction

of decision-making (10 items), defined as our four

key variables. In addition, three process variables

were measured, including: Perceived importance of

decision-making (3 items); Perceived effectiveness

of decision-making (3 items); and Perceived equity

of decision-making (3 items). Forty participants

were required to rate the extent to which they agreed

with each item using a 7 point Likert scale, with

choices ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘completely

agree’. The questionnaire was disseminated to the

members of LBHC both in ‘hard copy’ and an online

survey so that the participants could select their

preferred method of completion. Participants were

also asked to comment on their decision-making

processes and experiences within the LBHC to

provide context for the quantitative findings. Both

the quantitative and qualitative data will be collected

again once the DSS has been fully implemented,

thus allowing an evaluation of the implementation

process and DSS utility.

7 PRELIMINARY FINDINGS

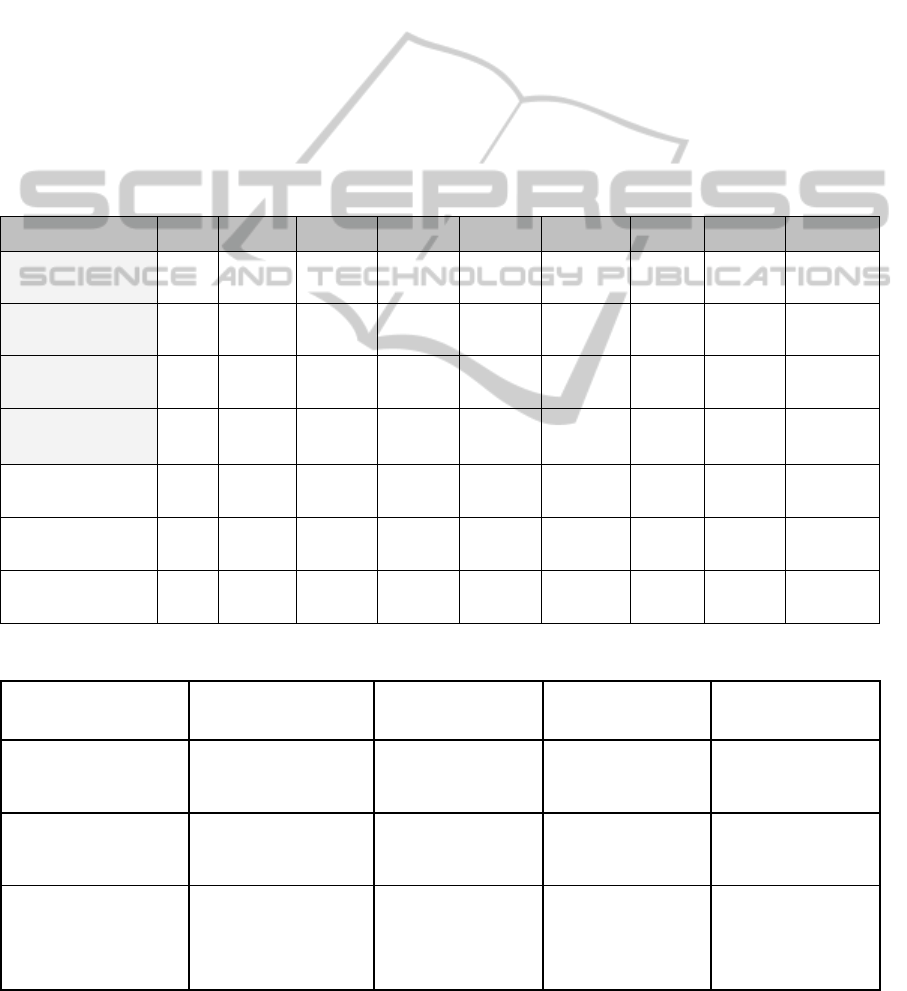

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics for each of

the decision-making domains. The findings indicate

that, overall, satisfaction with information for

decision-making and perceived effectiveness of

decision-making were rated lowest of the seven

domains. Conversely, perceived participation of

decision-making and perceived equity of decision-

making were rated highest. To further examine

Murray’s (2006) four domains, one way Analysis of

Variance (ANOVA) and Post Hoc tests were

conducted using different groups within the LBHC

as independent variables. Participants were first

divided into clusters representing the different types

of initiatives that were auspiced by the LBHC. Three

clusters were constructed to represent a focus on

governance (the board and administration), health

promotion (the Early Years Team, Health Promotion

scholars and the Multicultural Initiative) and disease

management/service integration (the GP Liaison

team, Information Management Initiative and

Optimal Health Team). A One Way ANOVA test

showed that consensus and participation tended to be

higher for the board than the other teams, but the

differences were not significant.

THINKING SPATIALLY, ACTING COLLABORATIVELY - A GIS-based Health Decision Support System for

Improving the Collaborative Health-planning Practice

151

Participants were then grouped into two major

age groups: 1) 0-40; 2) 40+. A One Way ANOVA

revealed a significance difference in the

accumulated means for the following variables,

participation, consensus and satisfaction with

information. Evidence-based decision-making

showed a trend towards significance. Specifically,

the younger age group reported lower scores on all

four key variables.

When grouped according to their duration of

membership in the LBHC, no significant differences

were found on any variables. The tenure groups

were constructed as follows: those who were new to

the LBHC (less than 12 months), intermediate

members (12-24 months) and veterans (more than 24

months). One Way ANOVA showed no significant

difference in the accumulated means. However, new

members and the veterans tended to report higher

scores than the intermediate age group. We then

tested the difference between accumulated means on

our four key variables across gender groups, with no

significant differences. Males tended to report higher

scores than females, but only represented 30% of our

sample.

The qualitative data provided by members

revealed further detail that might explain the

quantitative findings. For instance, one participant

noted that, ‘Very few decisions have ever been made

by the Board - most decisions are made by a few

outside the meeting, and therefore there is no rigour

or transparency to the processes’. Another

participant commented on the relative absence of

decision-making: ‘I'm not sure if any actual

planning for the future is made, with the exception

Table 1: Means, Standard Deviations and Frequencies of Responses to the 7 Domains of Decision-Making.

Dimension

Mean Standard

deviation

Not at all A Little Some Moderately Often Mostly Completel

y

Perceivedevidence‐

baseddecision‐making

4.33 2.18 3

(1.8%)

18

(11.0%)

27

(16.6%)

40

(24.5%)

32

(19.6%)

35

(21.5%)

8

(4.9%)

Perceivedconsensusof

decision‐making

4.55 2.24 4

(3.2%)

14

(11.1%)

17

(13.5%)

27

(21.4%)

18

(14.3%)

29

(23.0%)

17

(13.5%)

Perceivedparticipation

indecision‐making

4.80 2.32 4

(3.8%)

9

(8.7%)

14

(13.5%)

14

(13.5%)

20

(19.2%)

21

(20.2%)

22

(21.2%)

Perceivedsatisfaction

withinformationfor

decision‐making

3.49 2.22 50

(14.9%)

55

(16.4%)

68

(20.3%)

55

(16.4%)

56

(16.7%)

50

(14.9%)

1

(.3%)

Perceivedimportance

ofdecision‐making

4.63 2.27 0

(0%)

9

(9.2%)

23

(23.5%)

17

(17.3%)

10

(10.2%)

24

(24.5%)

15

(15.3%)

Perceivedequityof

decision‐making

4.77 2.31 6

(7.2%)

3

(3.6%)

6

(7.2%)

9

(10.8%)

30

(36.1%)

23

(27.7%)

6

(7.2%)

Perceivedeffectiveness

ofdecision‐making

3.83 2.26 8

(8.2%)

13

(13.4%)

16

(16.5%)

24

(24.7%)

17

(17.5%)

18

(18.6%)

1

(1.0%)

Table 2: Comparison of selected four key variables with LBHC major age groups.

LBHC Affiliation by two

major groups

Perceived evidence-based

decision-making

Perceived consensus of

decision-making

Perceived participation of

decision-making

Perceived satisfaction with

information of decision-

making

0-40 - young

Mean = 3.9

Std. Deviation = 1.1

N = 11

Mean = 3.6

Std. Deviation = 1.4

N = 11

Mean = 3.7

Std. Deviation = 1.1

N = 11

Mean = 2.3

Std. Deviation = 1.5

N = 10

40+ veterans

Mean = 4.7

Std. Deviation = 0.8

N = 13

Mean = 5.0

Std. Deviation = 1.2

N = 13

Mean = 5.4

Std. Deviation = 1.4

N = 14

Mean = 4.5

Std. Deviation = 1.3

N = 13

Statistics details

DF = 1

F = 3.7

SIG = .066

*non-significant(trended

towards significant)

DF = 1

F = 5.9

SIG = .02

* significant

DF = 1

F = 9.6

SIG = .005

* significant

DF =1

F = 13.8

SIG = .002

* significant

HEALTHINF 2011 - International Conference on Health Informatics

152

of recent 'planning sessions'. The lack of control

over decisions made by the coalition was a recurrent

theme in the qualitative comments; ‘I thought a

decision had been made prior to our input’.

However, the majority of comments made by

coalition members revealed the difficulty associated

with making decisions in the absence of adequate

information.

‘[We] need to identify priority actions, need

to be more pro-evidence in our decision

making’.

‘There is a serious lack of information and

communication [to guide decision-making] ‘.

The value of evidence-based decisions was clear

throughout the data; ‘If the LBHC goes down the

pathway of prioritising strategic directions based on

evidence, inclusive decision making processes

(including community input), this will have great

potential to more appropriately address [the]

issues’.

Despite high scores on consensus and

participation, some members noted that problems

existed in relation to the sense of connectedness of

the coalition “as a whole” and that this had a

significant impact on decision-making.

8 DISCUSSION

AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The preliminary quantitative and qualitative findings

of this study confirm that overall there were low

levels of satisfaction with the decision-making

processes across the LBHC. However, some groups

within the LBHC were more satisfied than others

(i.e., those who were over 40 years). There was also

a tendency for LBHC board members, males, new

members and veterans to be more satisfied with

information and perceive higher levels of consensus,

participation and evidence-based decision-making.

The data suggested that the lack of satisfaction with

information for decision-making may be due to the

complete lack of evidence on which to base

decisions. This lack of evidence seemed to

contribute to a sense of disconnectedness between

the different elements of the LBHC. For example,

some elements in the LBHC perceived that the

decision-making processes were not being practiced

consensually and in a participatory manner. The data

indicated that within some groups (i.e., Board), there

were high levels of consensus and participation, but

that this may not occur across the whole LBHC.

Further, there was an overall sense that decisions

were ineffective, presumably because they were not

based on information or evidence.

Although not significant, there was some

diversity across the components of the LBHC. Males

tended to be more satisfied as did those who had

been members of the LBHC for either longer or

shorter periods. This finding indicates the likelihood

of an acculturation curve for members (i.e., new

members are enthusiastic, but become more critical

of decision-making over time and then eventually

resolve this situation in some way – either by

withdrawing or seeking other sources of

information). Age of members had an important

influence on the way decision-making was

perceived. It is possible that younger people could

be more demanding in terms of their need for

involvement in the decision-making processes,

whereas veterans are likely to have access to more

intrinsic sources of information based on years of

experience in the region. As a result, they may be

less demanding of the decision-making processes.

As for the variation across the LBHC, the tendency

towards significant differences between the sub-

groups of the LBHC indicates that there may be

considerable diversity in decision-making that may

require different approaches to planning.

In summary, our findings have shown that there

is some diversity in the way members of a LBHC

view decision-making. They have also highlighted

the need for a comprehensive information

framework and collaborative process to underpin

planning for healthy cities, thus enabling health

coalitions to make effective decisions that engage all

stakeholders equitably. The framework proposed in

this paper would not only encourage planners to

engage with evidence and information about the

entire range of health determinants, but would also

provide a platform for collaboration and shared

engagement in the decision-making process.

Questions about how the framework and method are

actually applied in local communities, the impact of

the DSS on decision-making and its ability to

facilitate collaborative-based health planning,

remain unanswered and form the basis of this

ongoing research. These important research

questions will be addressed in the near future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is part of a broader ARC project named:

Coalitions for Community Health: A Community-

based Response to Chronic Disease. The authors

would like to acknowledge the investigators of this

THINKING SPATIALLY, ACTING COLLABORATIVELY - A GIS-based Health Decision Support System for

Improving the Collaborative Health-planning Practice

153

project, Elizabeth Kendall, Scott Baum, Heidi

Muenchberger and Tan Yigitcanlar.

REFERENCES

Bennett, C, Graham, ID, Kristjansson, E, Kearing, S. A.,

Clay, K. F. & O'Connor, A. M. (2010) Validation of a

Preparation for Decision Making Scale. Patient

Education and Counseling 78: 130-133 Elsevier.

Bishop, P. and Davis, G. (2001). Developing consent:

consultation, participation and governance. In Are You

Being Served? Eds. G. Davis and P. Weller. Sydney,

Allen & Unwin: 175–195.

Campbell, S. and Fainstein, S. S. (1996). Introduction: the

structure and debates of planning theory. In Readings

in urban theory, Eds. S. Campbell and S.S. Fainstein.

Oxford, Blackwell Publishing:1-16.

Cromley, E. K. and McLafferty, S. L. (2003). GIS and

public health. Health & Place 9(3): 279.

Dean J. R., J. W. and Sharfman, M. P. (1993). Procedural

rationality in the strategic decision-making process.

Journal of Management Studies 30(4): 587-609.

Duhl, L. J., & Sanchez, A. K. (1999). Healthy cities and

the city planning process. A Background

Documentation On Links Between Health And Urban

Planning, Copenhagen, WHO, Regional Office For

Europe.

Dur, F., Yigitcanlar, T. and Bunker, J. (2009). A decision

support system for sustainable urban development: the

integrated land use and transportation indexing model.

Proceedings of the Postgraduate Infrastructure

Conference. Brisbane, Australia, 26 March.

Queensland University of Technology.

Flood, P., Hannan, E., Smith, K., Turner, T., West, M., &

Dawson, J. (2000). Chief executive leadership style,

consensus decision making, and top management team

effectiveness. European Journal of Work &

Organizational Psychology 9(3), 401-420.

Flynn, B. C. (1996). Healthy cities: toward worldwide

health promotion. Annual Review of Public Health 17:

299-309.

Gudes, O., Kendall, E., Yigitcanlar, T., Pathak, V. and

Baum, S. (2010). Rethinking health planning: a

framework for organising information to underpin

collaborative health planning. Health Information

Management Journal 39 (2): 18-29.

Han J. H., Kendall, E., Sunderland, N., Gudes, O. and

Henniker, G. (2010) Chronic disease, geographic

location and socioeconomic disadvantage as obstacles

to equitable access to e-health. Health Information

Management Journal 39 (2): 30-36.

Healthy Cities Illawarra (2010). Working with the

community for a healthier, safer, greener and more

caring Illawarra. Wollongong: Illawarra city council.

Available at: http://www.healthycitiesill.org.au/

contactus.htm (Accessed 10 October 2010).

Higgs, G. and Gould, M. (2001). Is there a role GIS in the

'new NHS'? Health & Place 7(3): 247-59.

Mooney, G. and Fohtung, N.G. (2008). Issues in the

measurement of social determinants of health. Health

Information Management Journal 37(3): 26-30.

Murray, D. J. (2006). A critical analysis of communicative

planning theory as a theoretical underpinning for

integrated resource and environmental management.

Unpublished PhD thesis, Griffith University,

Queensland.

National Electronic Decision Support Taskforce. (2008).

Electronic Decision Support Systems Report.

Department of Health and Ageing. Canberra:

Australia.

NHHRC (2009). A healthier future for all Australians.

Canberra, ACT, National Health and Hospitals Reform

Commission.

Northridge, M. E., Sclar, E. D. and Biswas, P. (2003).

Sorting out the connections between the built

environment and health: a conceptual framework for

navigating pathways and planning healthy cities.

Journal of Urban Health 80(4): 556-568.

Parnell, J. A. and Bell, E. D. (1994). ‘The propensity for

participative decision making scale: A measure of

managerial propensity for participative decision

making.’ Administration & Society 25(4): 518-533.

Reeves, P. N. and Coile, R. C (1989). Introduction to

health planning. Arlington, VA: Information

Resources Press.

Reinke, W. A. (1972). Health planning: qualitative

aspects and quantitative techniques. Baltimore, MD:

Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and

Public Health, Department of Internet Health.

Schulz, A. and Northridge, M.E. (2004). Social

determinants of health: implications for environmental

health promotion. Health Education & Behaviour

31(4): 455-471.

Turban, E. (1993). Decision support and expert systems:

management support systems: Prentice Hall PTR

Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA.

Wave, V. (2009). mHealth for development: the

opportunity of mobile technology for healthcare in the

developing. United Nations Foundation and Vodafone

Foundation.

WHO (1997). Twenty steps for developing a healthy cities

project. WHO Regional Office of Europe.

WHO (1999). Health: creating healthy cities in the 21st

century. In The Earthscan reader in sustainable cities.

Ed. D, Satterthwaite. London, Earthscan: 137–172.

WHO (2010). Urban health Healthy Cities. Available at:

http://www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/health-

topics/environmental-health/urban-

health/activities/healthy-cities (Accessed 9 October

2010).

HEALTHINF 2011 - International Conference on Health Informatics

154

APPENDIX

Appendix: A conceptual framework for planning a healthy city (Modified after World Health Organization 1997; Schulz &

Northridge 2004).

THINKING SPATIALLY, ACTING COLLABORATIVELY - A GIS-based Health Decision Support System for

Improving the Collaborative Health-planning Practice

155