AN ABM OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SHARED MEANING

IN A SOCIAL GROUP

Enrique Canessa, Sergio E. Chaigneau

Facultad de Ingeniería y Ciencias & Centro de Investigación de la Cognición, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez

Balmaceda 1625, Recreo, Viña del Mar, Chile

Escuela de Psicología & Centro de Investigación de la Cognición, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez

Diagonal Las Torres 2640, Peñalolén, Santiago, Chile

Ariel Quezada

Escuela de Psicología & Centro de Investigación de la Cognición, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez

Balmaceda 1625, Recreo, Viña del Mar, Chile

Keywords: Agent-based modelling, Shared meaning, Conceptual content, Markov chain.

Abstract: Generally, concepts are treated as individual-level phenomena. Here, we develop an ABM that treats

concepts as group-level phenomena. We make simple assumptions: (1) Different versions exist of one

similar conceptualization; (2) When we infer that our view agrees with someone else’s view, we are subject

to true agreement (i.e., we really share the concept), but also to illusory agreement (i.e., we do not really

share the concept); (3) Regardless whether agreement is true or illusory, it strengthens a concept’s salience

in individual minds, and increases the probability of seeking future interactions with that person or source of

information. When agents interact using these rules, our ABM shows that three conditions exist: (a) All

versions of the same conceptualization strengthen their salience; (b) Some versions strengthen while others

weaken their salience; (c) All versions weaken their salience. The same results are corroborated by

developing probability models (conditional and Markov chain). Sensitivity analyses to various parameters,

allow the derivation of intuitively correct predictions that support our model’s face validity. We believe the

ABM and related mathematical models may explain the spread or demise of conceptualizations in social

groups, and the emergence of polarized social views, all important issues to sociology and psychology.

1 INTRODUCTION

Concepts appear to have a life-cycle in the cultures

in which they exist. Concepts are born at a certain

point in time, spread or not through culture, and die

out. Our view here is that the fate of concepts in

culture depends on their usefulness, and that a

concept is useful when it generates episodes of

shared meaning, thus allowing social cohesion and

the coordination of behaviour. Given that meaning is

something that happens in individual minds, how is

it possible that people agree about a meaning?

Psychological inquiry often assumes that meaning is

shared by resorting to direct reference, i.e., by

pointing to the referred object, rather than by

describing it (Brennan & Clark, 1996; Brown-

Schmidt & Tanenhaus, 2008; Carpenter, Nagell, &

Tomasello, 1998; Clark & Krych, 2004; Galantucci

& Sebanz, 2009; Garrod & Anderson, 1987; Moses,

Baldwin, Rosicky, & Tidball, 2001; Richardson,

Dale & Tomlinson, 2009; Tomasello, 1995). Though

this approach may work for concrete objects, it does

not solve the problem of how people agree about the

meaning of diffuse objects (abstract entities like,

e.g., democracy, womanhood, happiness). Direct

reference does not apply for these objects because

they lack clear spatio-temporal limits, thus

preventing the use of direct reference in interactions.

Furthermore, everyday concepts like those

illustrated above are notoriously ill-defined; making

shared meaning even more mysterious (Rosch &

Mervis, 1975). In our current work, we hold the

view that shared meaning is possible because

meaning is conventional, i.e., there is a limited set of

5

Canessa E., Chaigneau S. and Quezada A..

AN ABM OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SHARED MEANING IN A SOCIAL GROUP .

DOI: 10.5220/0003120100050014

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART-2011), pages 5-14

ISBN: 978-989-8425-41-6

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

meanings that apply to a given situation (Lewis,

1969; Lewis, 1975; Millikan, 2005). Constraining

the number of concepts that apply on a given

occasion, makes agreement a tractable problem.

However, even if a group of people has developed

conceptual conventions, the likely case is that each

person instantiates a somewhat different version of

those concepts (e.g., people may conceptualize

“leadership” in slightly different ways).

Furthermore, even if a group of people has

conventions about more or less dichotomous

concepts (e.g., “cowardice” and “courage”), a person

could still be wrong about which one is being

deployed by someone else at a given moment (e.g.,

if someone says “suicide”, she may be thinking of

“cowardice” while I may be thinking of “courage”).

Consequently, an individual can never know for sure

whether someone else agrees or not with his

conceptualization of a given event (even when being

explicit). Agreement is a probabilistic inference

(Chaigneau & Gaete, in preparation).

The ABM we report here focuses on two

probabilities that represent the abovementioned

inference. First, the probability of true agreement

(symbolized by p(a1)), which stands for the

probability that two agents (an observer and an

actor) agree on something given that they instantiate

different versions of the same concept (i.e., the

“leadership” example above). Second, the

probability of illusory agreement (symbolized by

p(a2)), which stands for the probability that observer

and actor agree, given that they instantiate different

concepts altogether (i.e., the “courage” or

“cowardice” example above).

2 CONCEPTUAL DESCRIPTION

OF THE ABM

Our current ABM represents a social group which

has a set of conventional conceptual states that, for

ease of exposition, we will call the focal set. These

states can represent different versions of the same

concept (e.g., different versions of “leadership”; or a

set of closely related concepts, such as “miserly”,

“stingy”, “scrooge”). Our p(a1) probability reflects

the degree of overlap between the different versions

in the focal set (greater overlap implies greater

probability of true agreement). Our p(a2) probability

reflects the degree of contrast against alternative

conceptualizations (lower contrast implies greater

probability of illusory agreement). The system

models the dynamical trajectories of concepts as

they become increasingly or decreasingly relevant

for agents depending on their capacity to generate

agreement of any type.

In each simulation run, agents act as observers

and actors. Observers seek evidence that actors share

their concept. Actors have a certain probability that

they will or will not act according to the focal set

concept. If they act according to the focal set

concept, that specific interaction has a probability

p(a1) of providing observers evidence of a shared

concept. If actors don’t act according to the focal set

concept (i.e., they act according to the contrast

concept), that specific interaction has a probability

p(a2) of providing observers evidence of a shared

concept.

We make some very simple and quite generally

accepted assumptions about our agents’ psychology.

If the observer witnesses evidence (blind to whether

it is true or illusory agreement), then his own

conceptual state increases its relevance in his mind

(i.e., our cognitive assumption; c.f., Evans, 2008;

Brewer, 1988; Lenton, Blair & Hastie, 2002), will be

more likely to guide his behaviour in the future (i.e.,

our motivational assumption; c.f., Rudman &

Phelan, 2008), and the observer will want to interact

with that particular agent again in the future (i.e., our

social assumption; c.f., Nickerson, 1998).

3 ABM IMPLEMENTATION

The theory presented in section 2 is implemented in

an agent-based model (ABM). In summary, the

ABM represents how concepts spread and get

stronger (or weaker) in a social group, by observing

the behaviour of other members. In the ABM, each

individual is an agent (actor, A), which acts

according to its concept with probability equal to the

strength of the concept. That behaviour is observed

by another agent (observer, O), and that changes the

strength of its concept. In general, if the observed

behaviour agrees with the behaviour expected from

O’s concept, then O’s concept strengthens.

Conversely, if the observed behaviour differs from

what is expected from that concept, then O’s concept

weakens. Concurrently, the agents begin to interact

more frequently with those that have strengthened

their concepts. In the following paragraphs we

describe the details of the ABM.

In the social group that the ABM represents, one

can set the number of members that belong to the

group. Each agent can have one of five different

related concepts or versions of the same concept and

each of the concepts or versions is represented by a

ICAART 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

6

number in the [0, 1] interval, labelled the coefficient

of the concept. This coefficient determines the

probability that an agent behaves according to the

given concept. The initial values of the coefficients

are sampled from a normal distribution with a mean

and standard deviation, which can be set. The model

checks that the assigned coefficients will always

remain in the [0, 1] interval.

Agents modify the strength of their concept’s

coefficients by observing the behaviour of other

agents. Every time they see behaviour consistent

with their concepts, the corresponding coefficients

are incremented by 0.02. On the other hand, if the

observed behaviour is not consistent with their

concepts, the corresponding coefficients are

decremented by 0.02. The model makes sure that the

coefficients always remain inside the [0, 1] interval.

Thus, when an agent sees that another agent acts

according to its concept, it is more probable that the

agent will act according to its own concept in the

future. These actions spread concepts throughout the

group.

Agents develop interaction preferences as they

observe each other. Specifically, agents will tend to

interact more frequently with agents who have

confirmed their concepts in previous interactions,

and indirectly, they will be less likely to interact

with those that have not confirmed their concepts.

This aspect of the ABM limits the diffusion of

concepts, given that it imposes certain heterogeneity

to the diffusion speed of the concepts. It could even

cause the weakening of some concepts among

certain members of the group. To simulate this

aspect of our theory, each agent has an interaction

probability with the rest of the agents. Taking into

account computational restrictions, those

probabilities take only discrete values (0.08, 0.11,

0.17, 0.26 and 0.38, probabilities which increase by

approximately 50% between successive values). At

the start of a simulation run, all the agents are

assigned a probability equal to 0.08, which means

that an agent will randomly interact with any other

agent. Then, as the run advances, if agent A

confirms O’s concept, agent O will increase its

interaction probability with A to the immediately

larger value. For example, if agent A’s interaction

probability was 0.08, then agent A will increase that

probability to 0.11.

A last aspect incorporated in the ABM is that in a

social group, it might exist more than one version of

a concept. Thus, the model allows setting the

number of versions that will be present in a group

between 1 and 5. Each version will be assigned to a

number of agents equal to the total number of agents

in a group divided by the number of versions.

Each agent O determines whether its concept

will strengthen or weaken according to the following

rules:

a) If A acts according to its own concept in the

focal set, and A’s conceptual content completely

coincides with O’s conceptual content, then O’s

concept will strengthen with probability equal to 1.

b) If A acts according to its own concept in the

focal set, and that concept is a version of the same

concept in O’s focal set (but not identical), then O’s

concept will strengthen with probability equal to

p(a1)and will weaken with probability equal to 1 -

p(a1).

c) If A does not act according to its concept in the

focal set (i.e., acts according to a contrasting

concept), and the contrasting concept overlaps

somewhat with the O’s concept in the focal set, then

O’s concept will strengthen with probability equal to

p(a2) and will weaken with probability equal to 1 -

p(a2).

d) If A does not act according to its concept in the

focal set (i.e., acts according to a contrasting

concept), and A’s conceptual content completely

coincides with O’s conceptual content, then O’s

concept will weaken with probability equal to 1.

Finally, each simulation cycle or step of the ABM is

composed of the following actions:

i) From the set of all agents, randomly select

without replacement an observer agent (O).

ii) O selects one actor agent (A), according to the

interaction probabilities that O has for the rest of the

agents.

iii) A behaves according to its concept with

probability equal to the value of the coefficient of

the concept that it has.

iv) O observes that behavior and modifies its

coefficient of the concept, according to the rules that

were previously described.

v) Repeat steps i) through iv) until all agents have

been observers.

We acknowledge that this description may not

provide the reader with a complete understanding of

our ABM. Space restrictions preclude providing

greater detail. In lieu, the ABM is available as a zip

file. The interested reader can download it from

http://www.uai.cl/images/stories/CentrosInvetigacio

AN ABM OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SHARED MEANING IN A SOCIAL GROUP

7

n/CINCO/CAT_1_English.zip. To run it, you will

need first to install Netlogo version 4.0.4

(http://ccl.northwestern.edu/netlogo/). Once on the

ABM interface, do the following steps to run a

simulation: (1) Input the simulation parameters, be it

with the slider controls or typing the desired p(a1)

and p(a2) values in the appropriate windows. (2)

Press SETUP. (3) Press SIMULATE. (4) If you

want to pause a run, simply press SIMULATE (you

will need to press it again to resume).

4 PRELIMINARY RESULTS

Once the ABM was implemented and verified, we

carried out several runs to assess the dynamics of the

coefficients of the concepts that emerged. After

gaining some insights into the dynamics of those

coefficients and how different combination of

parameters changed those dynamics, we performed

experiments fixing the value of some parameters as

follows: number of agents = 100; number of

versions of a concept (or number of related

concepts) = 5; initial value of coefficients of

concepts = 0.5; and changing the value of p(a1) and

p(a2) between 0.1 and 0.95. According to the

combination of values for p(a1) and p(a2), three

different dynamics emerged.

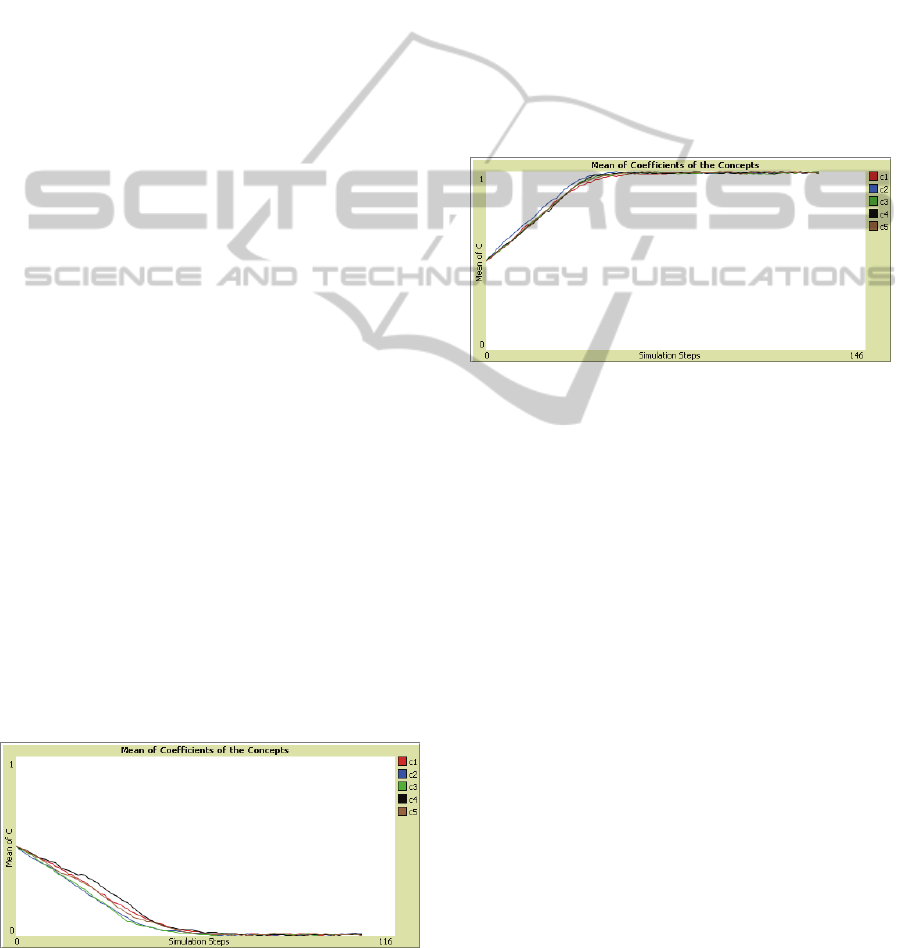

4.1 Convergence to Zero

When we set small values for p(a1) and p(a2), for

example p(a1) = 0.1 and p(a2) = 0.2, then the

coefficients rapidly decrease and get close to zero,

remaining at that value. This can be seen in Figure 1,

where we plotted the mean value of the coefficient

of each version of the concept (c1 through c5) over

simulation steps. The mean value of each coefficient

is calculated by averaging the individual value of the

coefficient of the agents that have each version of

the concept.

Figure 1: Mean of coefficients of concepts (c1 through

c5), for p(a1) = 0.1 and p(a2)= 0.2.

That happens because the probability that O

observes a behaviour consistent with its concepts is

very low, since p(a1) and p(a2) are small. Thus, in

general, concepts tend to weaken, which in turn

makes it more probable that the coefficients will

keep decreasing throughout the run. Conceptually,

this is equivalent to concepts that are not useful to

generate agreement in a social group, and rapidly die

out.

4.2 Convergence to One

When both p(a1) and p(a2) are set to large values,

for example p(a1) = 0.8 and p(a2) = 0.9, then the

coefficients quickly increase and take values close to

1.0. This can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Mean of coefficients of concepts (c1 through

c5), for p(a1) = 0.8 and p(a2) = 0.9.

Contrary to what happened in 4.1, in this

situation p(a1) and p(a2) are large, thus favouring

that O observes a behaviour consistent with its

concepts, which will strengthen the coefficients. In

turn, this makes more probable that in successive

cycles, all the coefficients of the concepts will

increase. Conceptually, this is equivalent to a group

of related concepts synergistically increasing their

relevance by promoting agreement in culture.

4.3 Bifurcation

Using different combinations for p(a1) and p(a2),

such as (0.20, 0.80), (0.60, 0.40), (0.80, 0.16), we

saw that some concepts tended to strengthen and

others to weaken. We labelled this type of dynamic a

“bifurcation”, which is shown in Figure 3.

Under this condition, a relatively large value of

p(a1) or p(a2), but not of both of them, will promote

that on each run some Os observe behaviours

consistent with their concepts. However, since p(a1)

or p(a2) will have a small value, it will also happen

that on each run some Os will not observe

behaviours consistent with their concepts. Thus,

some versions of the concept will strengthen and

ICAART 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

8

others weaken in agents’ minds. Conceptually, this

is equivalent to a group of related concepts that have

a weakly contrasting (i.e., somewhat overlapping)

conceptual alternative, such as might be the case of

concepts of male versus female gender, and concepts

of liberal versus conservative political views.

Concepts like these tend to become polarized in

large social groups, just as occurs in our model’s

bifurcations.

Figure 3: Mean of coefficients of concepts (c1 through

c5), for p(a1) = 0.2 and p(a2)= 0.8.

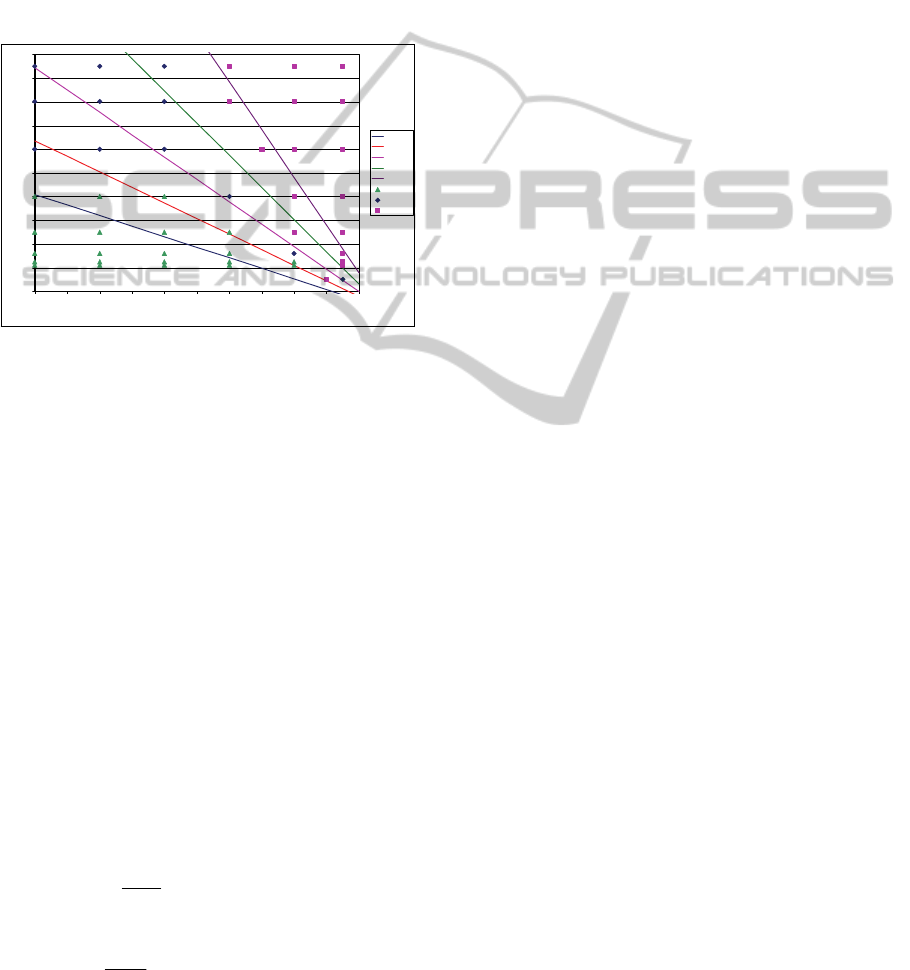

4.4 Map of Dynamics

Since we realized the significant influence of p(a1)

and p(a2) on the type of dynamics that emerged, we

ran simulations using more combinations for these

two variables. The types of dynamics of the

coefficients that emerged are presented in Figure 4.

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

p(a1)

p(a2)

Bifurcation 1 0

Figure 4: Dynamics that emerge for coefficients of

concepts, according to values set to p(a1) and

p(a2)(bifurcation, 1 = convergence to 1, 0 = convergence

to 0).

We confirmed that for small values of p(a1) and

p(a2), we obtained convergence to zero; for large

values of p(a1) and p(a2), we saw convergence to

one; and for other combinations of those parameters,

we observed a bifurcation. Interestingly, note that

the combinations for p(a1) and p(a2), for which we

obtain a bifurcation, approximately lie on a line

connecting the lower right corner of the graph with

the upper left one. Moreover, see that the zone

where we get the bifurcation gets wider at the upper

left corner. That means that at the lower right corner

(p(a1) >> p(a2)), the dynamics of the ABM gets

more sensitive to the combination of p(a1) and p(a2)

than at the opposite corner (p(a1) << p(a2)). Since

that behaviour of the ABM was quite intriguing, we

developed another model to try to explain such

behaviour.

5 PROBABILISTIC

AND MARKOV CHAIN MODEL

To begin to validate the ABM results, and more

formally explain the conditions under which the

three dynamics appeared, we developed a simple

probabilistic model. This initial model justified why

the bifurcation emerged when the values for p(a1)

and p(a2) roughly lie on a line connecting the lower

right corner of the graph with the upper left one, as

shown in Figure 4.

5.1 Simple Conditional Probability

Model

To explain the three different types of dynamics that

emerge from the ABM, we use a simple conditional

probability model to calculate an initial probability

that a concept will strengthen (p

if

). If p

if

is small,

then most probably, the coefficient, which represents

the concept, will decrease. On the other hand, if p

if

is

large, the coefficient will increase. If p

if

is about 0.5,

then we obtain the ideal situation under which a

bifurcation might occur, i.e. each coefficient will

have a 50% chance of decreasing and a 50% chance

of increasing, thus making it possible that about half

of them will diminish and half of them will augment.

Figure 5 shows a conditional probability tree that

helps calculate p

if

.

In this model, p

if

depends on whether an agent A

(actor) behaves according to its concept (event BC),

which has probability equal to the initial value of the

coefficient that we set (c

0

), or not (event NBC, with

probability 1 - c

0

). Then, if A acts according to its

concept, then there is a p

i

probability that A and O

share all their conceptual content (event SACC), and

a 1- p

i

probability that they don’t share it all (i.e.,

each has a different version of the same concept,

event NSAAC). If they share all their conceptual

content (with probability pi), then it is certain that O

will strengthen its concept’s coefficient. If they

share versions of the same concept (with probability

AN ABM OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SHARED MEANING IN A SOCIAL GROUP

9

1-p

i

), then it is less than certain (p(a1)) that O will

strengthen its concept.

Figure 5: Conditional probability tree for calculating p

if

.

On the other hand, if A does not behave

according to its concept (event NBC), and A and O

share all their conceptual content (event SAAC, with

probability p

i

), then O’s concept will certainly

weaken. Alternatively, if A and O do not share all

their conceptual content (event NSAAC), then it

might happen that A provides O with some portion

of the conceptual content, and thus O’s concept

might strengthen with probability p(a2).

Solving the probability tree of Figure 5 for p

if,

we

obtain:

pp

c

ppp

c

p

aiiaiif 2

0

1

0

)1)(1()]1([ −−+−+=

(1)

In (1), remember that p

i

corresponds to the

probability that agents share all their conceptual

content, i.e. that they have the same version of a

concept. Thus, we can calculate p

i

for the beginning

of a run. In such initial condition, we will have N/V

agents with the same version of a concept, where N

equals the total number of agents and V is the

number of different versions of a concept. Then, the

initial probability that agent O will interact with an

agent A that has the same version of the concept will

be equal to the number of other agents that have the

same version as O has (without counting O), divided

by the total number of agents (without counting O):

1

1

−

−

=

N

V

N

p

i

(2)

For the value of the parameters used in the runs, N =

100 and V = 5, so that p

i

= 19/99 = 0.1919.

Now, if we set p

if

= 0.5 in (1), i.e. the ideal

condition for obtaining a bifurcation, and establish

c

0

= 0.5 (the value we used in our simulation runs),

we can get equation (3), which states the ideal

condition for p(a1) and p(a2) for getting a

bifurcation.

0.1

21

=+

pp

aa

(3)

Note that (3) does not contain p

i

, which means

that that condition applies for any value of p

i

.

Equation (3) corresponds to a line with an intercept

with the y axis (p(a2) axis) equal to 1.0 and slope

equal to -1.0, which coincides with the line depicted

in Figure 4 that represents the combinations of p(a1)

and p(a2) where we obtained a bifurcation. Now, if

the sum of p(a1) and p(a2) is bigger than 1.0, we

obtain a parallel line to (3), but located above (3). In

that case, p

if

is larger than 0.5, and thus most

probably the coefficients will converge to one. This

coincides with the region of combinations for p(a1)

and p(a2), shown on Figure 4, where the coefficients

converge to one. To see that, we can rewrite (1),

replacing c

0

= 0.5:

p

pp

pp

i

iif

aa

−

−

=+

1

2

21

(4)

If we replace in (4) p

i

for its value 0.1919 and,

for example, set p

if

= 0.6, we obtain p(a1) + p(a2) =

1.248. On the other hand, if the sum of p(a1) and

p(a2) is smaller than 1.0, we also obtain a parallel

line to (3) but located below (3). In this case, p

if

will

be smaller than 0.5, and thus we will get a

convergence to zero of the coefficients. For

example, if we put p

if

= 0.4 in (4), we get the line

p(a1) + p(a2) = 0.753. That line is located within the

region of combinations of p(a1) and p(a2) shown in

Figure 4, where we obtain that dynamic.

However, from Figure 4, we can also see that on

the upper left corner of the graph, the line p(a1) +

p(a2) = 1.0 does not represent all the combinations

of p(a1) and p(a2) where the ABM exhibits the

bifurcation. Thus, the simple probability model only

partially explains the empirical results.

5.2 Markov Chain Model

Since the model in 5.1 calculates p

if

only for the

initial state of a simulation run, it cannot fully

capture the dynamical nature of the ABM.

Remember that the concepts’ coefficients change

during a run, as well as the interaction probabilities

among agents. In the ABM, that means that c

0

and p

i

p

if

BC: c

0

NBC: 1 – c

0

SAAC: p

i

NSAAC: 1 - p

i

1.0

p(a

1

)

p(a

2

)

0.0

SAAC: p

i

NSAAC: 1 - p

i

ICAART 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

10

will change as the simulation run advances. Thus,

we need to build a model that captures that

dynamical aspect of the ABM. To do so, we use a

simple Markov chain, with four states, as described

in Table 1.

Table 1: State transition probability matrix of the Markov

chain.

S

t+1

(

j

= 0) W

t+1

(

j

= 1)

S

t

(i = 0) p

i

f

+

1 - p

i

f

+

W

t

(i = 1) p

i

f

-

1- p

i

f

-

Table 1 indicates that if a concept strengthens

(state S

t

(i = 0)), then the probability that it will

increase in the next step (state S

t+1

(j = 0))

is p

if

+

, and

that it will weaken is 1 - p

if

+

(state W

t+1

(j = 1)). On

the other hand, if a concept weakens (state W

t

(i =

1)), then the probability that it will strengthen in the

next step (state S

t+1

(j = 0)) is p

if

-

and that it will

weaken (state W

t+1

(j = 1)) is 1- p

if

-

. In the ABM,

each of those p

if

has a meaning. From expression (1),

we know that p

if

depends on c and p

i

, which change

during a simulation run. The description of the ABM

states that if a concept strengthens, then its

coefficient will increase by a certain

Δ

c, and the

same will happen with p

i

, which will increase by

Δ

p

i

. If the concept weakens, then the coefficient c

will decrease by

Δ

c, but p

i

will remain the same.

Therefore, using those facts, we can write the

following expressions for p

if

+

and p

if

-

:

0

(, ) ,

if i i i i

if

with c

p

pppp

ccc

p

++

++

+

=+Δ = +Δ=

(5)

0

(, ) ,

if if i i i

w ith c

pp p pp

ccc

−− −

−−

==−Δ=

(6)

Then, replacing (5) and (6) in (1), we can write the

explicit equations for p

if

+

and p

if

-

:

01

0

2

)[( ) (1 )]

(1 )(1 )

(

if i i a i i

iia

c

c

p

cppppp

ppp

c

+

=+Δ +Δ+ −−Δ

+− −Δ − −Δ

(7)

01

0

2

)[ (1 )]

(1 ) (1 )

(

if i a i

ia

c

c

pc pp p

pp

c

−

=−Δ + −

+− +Δ −

(8)

Now, if we apply the properties of an ergodic

Markov chain (c.f. Ross, 1998), we can compute a

long-run probability that a concept will strengthen

(

Π

0

):

pp

p

ifif

if

+−

−

−+

=

Π

1

0

(9)

Since (9) is written in terms of p

if

+

and p

if

-

, which

in turn are given by (7) and (8), it would be rather

cumbersome to write an explicit equation for (9) in

terms of c,

Δ

c, p

i

,

Δ

p

i

,

p(a

1

) and p(a

2

). Thus, we

prefer to use the following definitions and write a

simpler expression for

Π

0

:

00

00

00

() ()( )

()(1) ()( )

(1 )(1 ) (1 )( )

1

1

iii

iii

iii

ac ec

bc f c

dc gc

ppp

cc

ppp

cc

ppp

cc

=−Δ =+Δ +Δ

=−Δ− =+Δ −Δ

=− +Δ − =− −Δ −Δ

−

−

(10)

Then, using (10), we can write:

12

0

12 12

1

aa

aa aa

ab d

ab d e f g

pp

p

ppp

++

=

++ + −− −

Π

(11)

Expression (11) can be rearranged so that it looks

similar to equation (4), i.e. represents a line that

states the relationship that must exist between p(a1)

and p(a2) for a given

Π

0

:

00 000

21

00 00

aa

bfb a ae

dgd dgd

pp

+− +−+

=+

−− −−

ΠΠ ΠΠΠ

ΠΠ ΠΠ

(12)

Note that (12) is an equation of a line with a slope

equal to the expression located to the left of p(a1)

and an intercept with the y axis (p(a2) axis) equal to

the far right hand expression. If we compare (12)

with (4), we can see that the slope in (4) does not

change, depending on the values that p(a1), p(a2)

and p

if

take; but in (12) the slope changes (remember

that p

if

in (4) is equivalent to

Π

0

in (12)). Moreover,

if we set in (10), c

0

= 0.5, p

i

= 0.1919,

Δ

c = 0.45 and

Δ

p

i

= 0.05; and put the values a through g, defined

in (10), in (12), we can get a family of lines that

represents the condition that must meet p(a1) and

p(a2) for obtaining different values of

Π

0

. Figure 6

shows the same graph presented in Figure 4, but

displaying lines for

Π

0

= 0.3 to 0.7 according to the

Markov chain model that corresponds to expression

(12).

From Figure 6, we can see that the line for

Π

0

=

0.5 (the ideal condition for getting a bifurcation)

approximately coincides with a line equal to the one

we calculated for the simple probabilistic model (see

expression (3) and Figure 4). The other lines for

Π

0

= 0.6 and 0.7 are located in the region where the

ABM exhibits the convergence to one dynamic and

the lines for

Π

0

= 0.3 and 0.4 lie in the region where

the convergence to zero dynamic emerges. Thus, we

can see that the Markov chain model represents

fairly well the conditions under which the ABM

AN ABM OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SHARED MEANING IN A SOCIAL GROUP

11

exhibits the three different dynamics. Moreover,

note that the lines tend to converge toward the lower

right corner of the graph, where p(a1) >> p(a2) and

tend to diverge toward the upper left corner, where

p(a1) << p(a2). This means, that the region where

we get the bifurcation and which separates the areas

where we obtain the convergence to one and zero,

gets narrower when p(a1) >> p(a2) and wider when

p(a1) << p(a2). That characteristic was the one that

the probabilistic model described in 5.1 was not able

to capture.

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

pa1

pa2

Πο = 0.3

Πο = 0.4

Πο = 0.5

Πο = 0.6

Πο = 0.7

0

Bif

1

Figure 6: Dynamics that emerge for coefficients of

concepts, according to values set to p(a1) and

p(a2)(bifurcation, 1 = convergence to 1, 0 = convergence

to 0) and lines for different values of Π

0

according to the

Markov chain model.

5.3 Sensitivity of Models to Changes in

Values of some Parameters

By analyzing the ABM’s and its associated

probabilistic models’ sensitivity to different

parameters, we are able to derive predictions for

“real world” situations. Although the Markov chain

model presented in 5.2 better explains the dynamical

properties of the ABM than the probabilistic model

described in 5.1, the latter model is easier to analyze

from a substantive point of view. Thus, based on

expression (1), we will compute the sensitivity of

that model to changes in values of some parameters.

Here, we will present only two results of such

analyses. To do so, we use (1) and take the partial

derivatives of p

if

with respect to p(a1) and p(a2):

)1(

0

1

p

c

p

p

i

a

if

−=

∂

∂

(13)

)1)(1(

0

2

p

c

p

p

i

a

if

−−=

∂

∂

(14)

Additionally, since p

i

appears in (13) and (14)

and that variable depends on the number of agents

and concepts (N, V see (2)), we can express (13) and

(14) in terms of N and V. Moreover, given that for

reasonably large values of N, p

i

tends to 1/V, we will

analyze (13) and (14) taking into consideration that

p

i

≈1/V.

From (13) and (14) we can see that the

sensitivity of p

if

with respect to p(a1) and p(a2) is

always positive (remember that 0 ≤ c

0

, p

i

≤ 1), i.e.

the larger p(a1) and p(a2), the larger p

if

. Now, the

larger the number of concepts a group has (V), the

smaller p

i

will be and the more influential p(a1) and

p(a2) will be on the value that takes p

if

. That means

that for groups with a large set of related concepts

(or many different versions of the same concept), the

probability of true and illusory agreement (p(a1) and

p(a2)) will greatly influence p

if

. The significance of

that influence will also be determined by the value

of c

0

. Note that for large values of c

0

, p(a1) will have

a larger influence on p

if

than p(a2) and vice-versa.

Thus, for groups with many concepts, the degree of

agreement, either true or illusory, and the initial

strength of each concept will dictate whether each

concept strengthens or weakens, and eventually

disappears.

Several “real world” situations could conform to

the dynamics described above. As an illustration,

imagine a social group that has an abstract concept,

such as conservative. Presumably, people would

have many different versions of such concept (i.e., a

small p

i

), with some people, e.g., considering that

conservative is a view about economics, while

others considering that it is a view about values, and

so on. Imagine, furthermore, that this concept’s

relevance in that society is moderate, in the sense

that it does not persistently determine people’s

actions (i.e., c

0

≠ 1). For concepts like this, our

sensitivity analyses predict that their fate as a

cultural phenomenon will depend mainly on their

capacity to generate agreement.

Imagine, furthermore, that conservative has

liberal as a weakly contrasting alternative concept

(liberal is weakly contrasting to conservative

because it does not clearly divide political opinion in

two sharply contrasting clusters). Our sensitivity

analyses predict that the fate of this pair will depend

on agreement, regardless of whether it is true (p(a1))

or illusory (p(a2)). Additionally, as discussed in 4.3

above, these conditions promote bifurcations akin to

social polarization.

Perhaps, an even more interesting situation arises

in groups that have a small number of concepts or

versions of them. In that case, p

i

will be large, and

ICAART 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

12

thus p(a1) and p(a2) will not have a large influence

on p

if

(i.e., the degree of true and illusory agreement

will not have a large influence on the fate of the

concepts). Examining Figure 5, we can see that in

the above mentioned situation, the fate of each

concept will be predominantly dictated by its initial

strength c

0

, i.e., an initially rather strong concept

will disseminate throughout the group and become

stronger, and an initially quite weak concept will die

out. Note that since in this situation, agreement of

any type is almost irrelevant, that implies that a

concept may spread even if people do not share the

same meaning of it.

Again, a “real world” situation that could

conform to these conditions is the following.

Imagine a social group in which an authority (moral,

political, or other) pushes an oversimplified concept

(e.g., a slogan), and creates the conditions to make it

relevant (e.g., punishes dissent). As occurs with

commands, slogans may leave little room for

alternative interpretations (i.e., p

i

is large), which, by

equations (13) and (14) implies that agreement

ceases to be the predominant force that drives that

concept’s path. In other words, if an authority

presents a very simple idea that allows little room

for alternative interpretations, and succeeds in

making it relevant in people’s minds (i.e., makes c

0

sufficiently large), that condition will be sufficient to

strengthen the concept and disseminate it throughout

the social group, regardless of whether its meaning

is shared or not.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In the work we report here, we use our ABM to

develop a complex theory about the dynamics of

shared meaning in social groups. This use of ABMs

is not new, and has been advocated by Ilgen and

Hulin (2000). Our ABM embodies some very simple

rules of interaction, in keeping with Axelrod’s

(1997) KISS principle. However, the ABM’s

dynamics are not simple, as attested by the expanded

region of combinations of p(a1) and p(a2) in Figure

4, where bifurcations emerge.

Our theory development approach to Agent

Based Modeling led us to formalize the dynamics

through increasingly refined probabilistic models.

Not only is this currently allowing us to recursively

improve our ABM, but it also allowed us to clearly

link the conceptual and mathematical formulations

of our theory (respectively, sections 1 and 2, and

section 5), and to gain a more general and clear

understanding of the ABM’s dynamics.

It is true that our model is, at this point, purely

theoretical, and that it requires data to support it.

However, we incorporated into the ABM generally

accepted psychological theory, and as our sensitivity

analyses in 5.3 show, the ABM makes intuitively

correct predictions that were not built into it in an ad

hoc fashion. These two aspects, we think, are at least

evidence of the ABM’s face validity. We would be

very disappointed if future work shows that this

validity is only illusory.

REFERENCES

Axelrod, R. (1997). Advancing the Art of Simulation in

the Social Sciences. in Simulating Social Phenomena.

Rosario Conte, Rainer Hegselmann and Pietro Terna

Eds. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Brennan, S. E. & Clark, H. H. (1996). Conceptual pacts

and lexical choice in conversation. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and

Cognition, 22, 1482–1493.

Brewer, M. B. (1988). A dual process model of impression

formation. In T. K. Srull and R. S. Wyer Jr. (Eds.),

Advances in Social Cognition (pp. 1–36), Hillsdale,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Brown-Schmidt, S. & Tanenhaus, M. K. (2008). Real-time

investigation of referential domains in unscripted

conversation: A targeted language game approach.

Cognitive Science, 32, 643–684.

Carpenter, M., Nagell, K. & Tomasello, M. (1998). Social

cognition, joint attention, and communicative

competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs

of the Society for Research in Child Development,

63(4), 1-143.

Chaigneau, S. E. & Gaete, J. (2010). Agreement in

Conventionalized Contexts. Manuscript presented for

publication.

Clark, H. H. & Krych, M. A. (2004). Speaking while

monitoring addressees for understanding. Journal of

Memory and Language, 50(1), 62-81.

Evans, J. St. B. T. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of

reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual

Review of Psychology, 59, 255-278.

Galantucci, B. & Sebanz, N. (2009). Joint action: current

perspectives. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1, 255-259.

Garrod, S., & Anderson, A. (1987). Saying what you mean

in dialogue: A study in conceptual co-ordination.

Cognition, 27, 181–218.

Ilgen, D. R. & Hulin, Ch. L. (2000). Computational

modeling of behavior in organizations. Washington

D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Lenton, A. P., Blair, I. V., & Hastie, R. (2001). Illusions of

gender: Stereotypes evoke false memories. Journal of

Experimental Social Psychology, 37(1), 3-14.

Lewis, D. (1969). Convention: A Philosophical Study.

Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

AN ABM OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SHARED MEANING IN A SOCIAL GROUP

13

Lewis, D. (1975). Languages and Language. In Keith

Gunderson (Ed.), Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy

of Science, Volume VII (pp. 3–35). Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press.

Millikan, R. G. (2005). Language: A biological model.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moses, L. J., Baldwin, D. A., Rosicky, J. G. & Tidball, G.

(2001). Evidence of referential understanding in the

emotions domain at 12 and 18 months. Child

Development, 72, 718–735.

Nickerson, R. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous

phenomenon in many guises. Review of General

Psychology, 2, 175–220.

Richardson, D. C., Dale, R. & Tomlinson, J. M. (2009).

Conversation, gaze coordination, and beliefs about

visual context. Cognitive Science, 33, 1468-1482.

Rosch, E. & Mervis, C. B. (1975). Family resemblances:

Studies in the internal structure of categories.

Cognitive Psychology, 7, 573-605.

Ross, S. M. (1998). A First Course in Probability (5th

ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Rudman, L. A. & Phelan, J. E. (2008), Backlash effects

for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations.

Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 61-79.

Tomasello, M. (1995). Joint attention as social cognition.

In C. Moore & P. J. Dunham (Eds.), Joint attention:

its origins and role in development (pp. 103-130).

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

ICAART 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

14