A STUDY IN AUTHENTICATION VIA ELECTRONIC

PERSONAL HISTORY QUESTIONS

Ann Nosseir

Institute of National Planning, Salah Salem Street, Nasr City and British University in Egypt, El Shorouk City, Egypt

Sotirios Terzis

Department of Computer and Information Sciences, University of Strathclyde, 26 Richmond Street, Glasgow, U.K.

Keywords: Security Usability, Usable Authentication, Question-based Authentication, User Study.

Abstract: Authentication via electronic personal history questions is a novel technique that aims to enhance question-

based authentication. This paper presents a study that is part of a wider investigation into the feasibility of

the technique. The study used academic personal web site data as a source of personal history information,

and studied the effect of using an image-based representation of questions about personal history events. It

followed a methodology that assessed the impact on both genuine users and attackers, and provides a deeper

insight into their behaviour. From an authentication point of view, the study concluded that (a) an image-

based representation of questions is certainly beneficial; (b) a small increase in the number of

distracters/options used in closed questions has a positive effect; and (c) despite the closeness of the

attackers their ability to answer correctly with high confidence questions about the genuine users’ personal

history is limited. These results are encouraging for the feasibility of the technique.

1 INTRODUCTION

Passwords are widely used to authenticate users in a

variety of contexts. Their popularity stems from the

ease with which they can be implemented and

administered. They also have well understood

theoretical security properties. However, these

mechanisms also suffer from well-reported usability

problems (Brostoff, 2004, Yan et al, 2004). At the

heart of these problems lays the fact that passwords

that are difficult for attackers to guess are also

difficult for genuine users to remember. In other

words, secure passwords are not user-friendly.

In recent years, a number of usable

authentication schemes have been proposed that aim

to address the usability problems of passwords (De-

Angeli et al, 2002, Dhamija, 2000, Passface, Pering

et al, 2003, Wiedenbeck et al, 2005, Zviran and

Haga, 1990). Question-based authentication using

personal facts appears as a particularly promising

approach. Typically question-based authentication

schemes involve an answer registration step, in

which users set up one or more questions and their

answers, followed by an answer presentation step, in

which users are challenged by (some of) their

questions and are required to provide the registered

answers for successful authentication (Just, 2004).

However, the effectiveness of current question-

based authentication is limited. The number of

personal facts used is kept quite small and fairly

generic, and the answer registration phase is rarely

repeated (Just, 2004). The main idea of our research

is to improve the effectiveness of question-based

authentication by replacing answer registration by an

automated process that constructs questions and

answers from the electronic personal histories of

users.

Our approach is motivated by two main

observations, first detailed electronic records of

users’ personal histories are already available, and

second the use personal history information in

question-based authentication is appealing both from

a security and usability point of view. In today’s

world as users go about their everyday life, they

leave behind trails of digital footprints (Harper et al,

2008). These trails consist of data captured by a

plethora of information and communication

technologies when users interact with them. For

63

Nosseir A. and Terzis S. (2010).

A STUDY IN AUTHENTICATION VIA ELECTRONIC PERSONAL HISTORY QUESTIONS.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Human-Computer Interaction, pages 63-70

DOI: 10.5220/0002908000630070

Copyright

c

SciTePress

example, trails of shopping transactions are captured

by the information systems of credit card companies;

while mobile phone networks capture trails of

visited areas, etc. The abundance of cheap storage

space makes it easy to keep lasting records of these

trails (Harper et al, 2008). As the deployment and

use of information and communication technologies

becomes pervasive, people’s digital footprints come

closer to an electronic record of their personal

history. At the same time, personal history

information grows continuously over time. This

allows an increasing set of questions to be generated

for authentication purposes. Not only that but the

questions can also be personalized. Moreover,

authentication can also be dynamic, i.e. a different

set of questions and answers can be used at each

authentication attempt. All these make it more

difficult for an attack to succeed. In addition to this,

as electronic personal histories comprise of trails

from a variety of sources, it is also more difficult for

attackers to compromise the mechanism with a

successful attack against an individual data source,

or by impersonating the user in a particular context.

More importantly, though, these characteristics can

be provided with minimal impact on usability, as

users are likely to know quite well their personal

history and no additional effort is required from their

part.

This paper presents a study that was carried out

using data from academic personal web sites as a

source of personal history information. The study is

part of a series of studies that aim to establish the

appropriateness of personal history information as a

basis for question based authentication. The study

explores the extent to which participants could recall

events from their personal academic history and

successfully answer questions about them. At the

same time, it explores to what extent their colleagues

are able to answer the same set of questions. In

particular, the study investigates the impact of using

an image-based formulation of questions in the

ability of the participants to correctly answer them.

The main conclusions of the study are:

• Image-based formulation of questions has a

significant, positive impact on the ability of genuine

users to answer correctly the questions and no

significant impact on attackers.

• A small increase in the number of distracters in

closed questions has a significant negative impact on

the ability of attackers to answer them correctly and

no significant impact on genuine users.

• Despite the closeness of attackers to genuine

users, their ability in answering the genuine users’

questions correctly with high confidence is quite

limited.

The rest of the paper starts with a review of

related work, focusing on previous work on usable

authentication mechanisms. This review draws some

interesting conclusions that motivates our overall

approach and identifies some ideas for exploration.

This is followed by an outline of our general

research methodology that sets the context for the

current study. Then, the study itself is presented in

detail including the procedures followed, its results,

and the conclusions drawn. The paper concludes

with a summary and directions for future research.

2 RELATED WORK

In recent years, a number of usable authentication

schemes have been proposed that aim to address the

usability problems of passwords. These schemes can

be roughly classified into two categories, those that

use questions about personal attributes (facts and

opinions), which are easy to recall, and those that

use images, which are easy to recognise and recall.

The former category includes schemes like question-

based authentication (Just, 2004) and cognitive

passwords (Zviran and Haga, 1993), which uses

personal facts and opinions. The latter includes

mechanisms like random art (Dhamija, 2000),

Passfaces (Passface), personal images (Pering et al,

2003), Awas-E (Takada and Koike, 2003), and VIP

(De Angeli et al, 2002), which differ in the type and

origin of images, and the way these are used as

described below.

All these schemes involve a registration phase,

where the “password” is set up, and an

authentication phase where the user is challenged to

provide the “password”. At registration different

approaches require different levels of user

involvement. In some schemes the system selects the

“password” on users’ behalf. In others, users select a

password from a list of system provided ones. Some

even allow complete freedom to users in choosing

their “password”. During authentication, some

schemes challenge users to provide the complete

“password”, while others only part of it. Others go

further and challenge users with a series of

challenges/questions. In some schemes the questions

are open, where the user has to provide their

“password”, while in others closed, where the users

have to choose the password from a list of provided

ones. In general, it seems that the greater the user

involvement in the “password” registration phase,

the more memorable and applicable the “password”

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

64

is, while closed questions remove any repeatability

problems. Applicability refers to the extent to which

the chosen questions apply to the user population,

while repeatability refers to the extent to which the

correct answer does not have multiple syntactic

representations and its semantic value remains the

same over time (Just, 2004).

However, improving usability is not by itself the

end goal, as this improvement may be at the expense

of security. It is interesting to note that most usable

authentication schemes have been proposed without

an analysis of their robustness against attacks. More

specifically, a closed question only makes sense

from a security point of view, if measures are taken

to militate against brute-force attacks, e.g. large

number of distracters and multiple independent

questions, but the impact of such measures to

usability has not been fully assessed. Moreover,

questions-based schemes have been shown to be

vulnerable to guessability attacks by close friends

and family (Zviran and Haga, 1990). These

problems can be further exacerbated, if the questions

used have not been carefully chosen to ensure that

the correct answer cannot be uncovered with a small

number of attempts, or are publicly available (Just,

2004), particularly when users provide their own

questions. Similarly, for image-based schemes

studies have shown that users show statistically

significant biases in image selection (Davis,

Monrose and Reiter, 2004). The use of personal

images is fraught with even more difficulties and

dangers, as care needs to be taken to ensure that

images provided are not easily guessable (Pering et

al, 2003), because for example they include the user.

In addition to this, image-based schemes due to their

nature are also more vulnerable to shoulder surfing

and observation attacks.

We believe that a question-based authentication

scheme using electronic personal history information

has the potential to strike the right balance between

security and usability. First, as personal history

information grows over time, it should be more and

more difficult for others, even close family and

friends, to know it fully. The increase in the number

of potential questions should also make the scheme

more robust to guessability attacks and less

vulnerable to shoulder surfing, observation and brute

force attacks. Second, by asking questions about

events from the user’s personal history, the scheme

ensures maximum applicability with each user

potentially having their own questions. It also has a

potentially strong personal link essential for

memorability. In order to establish that these

properties hold in practice an in depth empirical

investigation of personal history information is

necessary.

3 METHODOLOGY

For personal history information to be deemed

appropriate for authentication purposes, one needs to

establish that users can easily recall events from

their personal history and can successfully answer

questions about them. One also needs to show that

others cannot successfully answer the same

questions and cannot easily impersonate users. In

this respect, of particular concern are those that

share parts of a user’s personal history. An added

complication is that the trails of digital footprints

comprising a user’s electronic personal history may

take various forms with different characteristics.

For these reasons, our work carries out a number

of studies, using different types of electronic

personal history data. Each type of data is used to

generate a number of questions focusing on

particular events of the participants’ personal

histories. Moreover, each study combines a study of

genuine user behaviour, in which participants are

asked to answer questions about their personal

history, with a study of attacker behaviour, in which

participants are asked to answer questions about the

personal history of other participants. The focus is in

establishing a statistically significant difference in

the ability of genuine users and attackers to answer

the same set of questions. Furthermore, each study

carries out a number of experiments that explore

whether certain parameters can improve the results,

by either improving genuine users’ performance or

deteriorating attackers’ performance, or both.

In this context, we have already carried out two

studies. The first (Nosseir et al, 2005) used

electronic personal calendar data that provide a clear

set of personal history events. It showed that only

questions about events that are recent, repetitive,

pleasant, or strongly associated with particular

locations produce statistically significant difference

in the ability of genuine user and attackers to answer

them correctly. However, this study was quite

limited, with a small number of participants, as

people were very reluctant to share their personal

calendar data. The second study used sensor data

generated by an instrumented research laboratory

(Nosseir et al, 2006). The study built on the earlier

results focusing only on events that are recent and

repetitive, and also showed a difference in the ability

of genuine users and attackers to answer the

questions correctly. An interesting thing about this

A STUDY IN AUTHENTICATION VIA ELECTRONIC PERSONAL HISTORY QUESTIONS

65

study was that personal history events had to be

inferred from the underlying sensor data. Despite

using a fairly basic algorithm, the inference proved

very accurate. However, this study was also quite

limited with a small number of participants, and the

sensor data although plentiful, only allowed person

arrival and departure events to be inferred.

For this study, academic personal web site data

are used to overcome the above limitations.

Academic personal web sites are easily accessible

and are usually rich in information about the

personal academic history of the person. This makes

it straightforward to generate a large variety of

personal history events, from teaching, research,

study and even leisure activities. In addition to this,

within an academic department some of these

activities will be shared, so participants will have

some shared history providing us with attackers that

are close to the participants they attack.

Furthermore, most academics nowadays have a

personal web site, providing us with a large pool of

potential participants.

Despite these advantages, we should make clear

that personal web sites, academic or otherwise, are

not an appropriate source of information for

authentication purposes, because all their

information is public and accessible to attackers.

That said, academic personal web sites, offer traces

of digital footprints similar to systems that are not

publicly available. As a result, they can be used to

draw conclusions about the appropriateness of

personal history information for authentication

purposes, provided that during the attack part of the

study participants do not have access to the web.

4 ACADEMIC PERSONAL WEB

SITE STUDY

4.1 Participants and Procedures

The study was conducted within an academic

department and twenty-four members of staff agreed

to take part, three women and twenty-one men with

an average age of forty-one. For all participants, we

analysed the information on their academic personal

web site in order to identify a number of events from

their history. Building on the results of our earlier

studies, we focused our attention on events that are

recent, repetitive, pleasant or strongly associated

with particular locations. These provided us with a

large collection of events about which to build

questions. The collection included events associated

with teaching, research, studies and leisure activities.

For example, teaching events included lectures and

tutorials the academic teaches, research events

included research group and project meetings, paper

publications and conference attendances, study

events included degrees awarded, while leisure

events included sports event attendances and

participation.

The study in accordance to the methodology

outlined above consisted of two parts: a genuine

users part and an attackers part. Its main goals were

first, to see whether there is any difference in the

ability of genuine users and attackers to answer

correctly questions about the personal history events

identified above, and second, to see what the effect

is of using an image-based formulation of questions

in the ability of genuine users and attackers to

answer them correctly. The latter goal was

motivated by the related work in the area of usable

authentication, where image-based schemes have

been shown to offer certain advantages with respect

to usability. Our intention was to examine whether

similar advantages will materialize in the context of

personal history information.

Figure 1: Example of "image of people" question.

Figure 2: Example of "image of place" question.

Figure 3: Example of map question.

With these goals in mind, from the identified events

for each participant we constructed four text-based

questions and two image-based ones. Unfortunately,

for a lot of the questions it was not possible to

construct reasonable image-based formulations. The

image-based questions were of three types: (a)

images of people, (b) images of places, and (c)

maps. The images used were all taken from the web.

The images of people were co-authors of published

papers, research project collaborators or the chairs of

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

66

attended conferences (see

Figure 1). In all cases, the

people were external to the department. The images

of places were pictures of bespoke buildings from

university campuses and conference venues, or

landmarks in the vicinity of conference venues (see

Figure 2). The maps were university campus maps or

conference venue maps (see Figure 3). All questions

generated were closed in order to avoid repeatability

problems in providing the answers. The questions

were either true/false or four-part multiple choice as

in some cases it was not possible to identify an

adequate number of reasonable distracters. The large

number of true/false and four-part multiple choice

for both text and image-based questions, presented

us with the opportunity to also explore the effect that

the number of options has to the ability of genuine

users and attackers to answer the questions.

The study was conducted through a series of

interviews, one with each participant. To facilitate

the attack part of the study and keep the overall

effort required by participants reasonable, they were

divided into three groups of eight. The groups were

formed alphabetically according to participants’

surnames. At the beginning of the interview each

participant was presented with a questionnaire, and

the aims of the study and procedures followed were

explained. The questionnaire consisted of eight

parts. In the first part the participant played the role

of a genuine user answering her own questions,

while in the remaining seven parts she played the

role of an attacker answering the questions of the

other participants of her group. In each attack, the

attacker was made aware who the target of the attack

was. In addition to answering the questions each

participant was also asked to indicate how confident

she was about each answer. For this purpose a five

point Likert scale was used, ranging from ‘very

unconfident’ to ‘extremely confident’. The aim of

the confidence scale was to gain a deeper insight

about the behaviour of genuine users and attackers

when answering the questions. The investigator

conducting the interview also noted the time it took

to answer each question. The purpose of this was to

see whether text and image-based questions require

a different amount of effort to answer them. Finally,

one of the participants that initially agreed to

participate failed to attend the interview.

4.2 Results

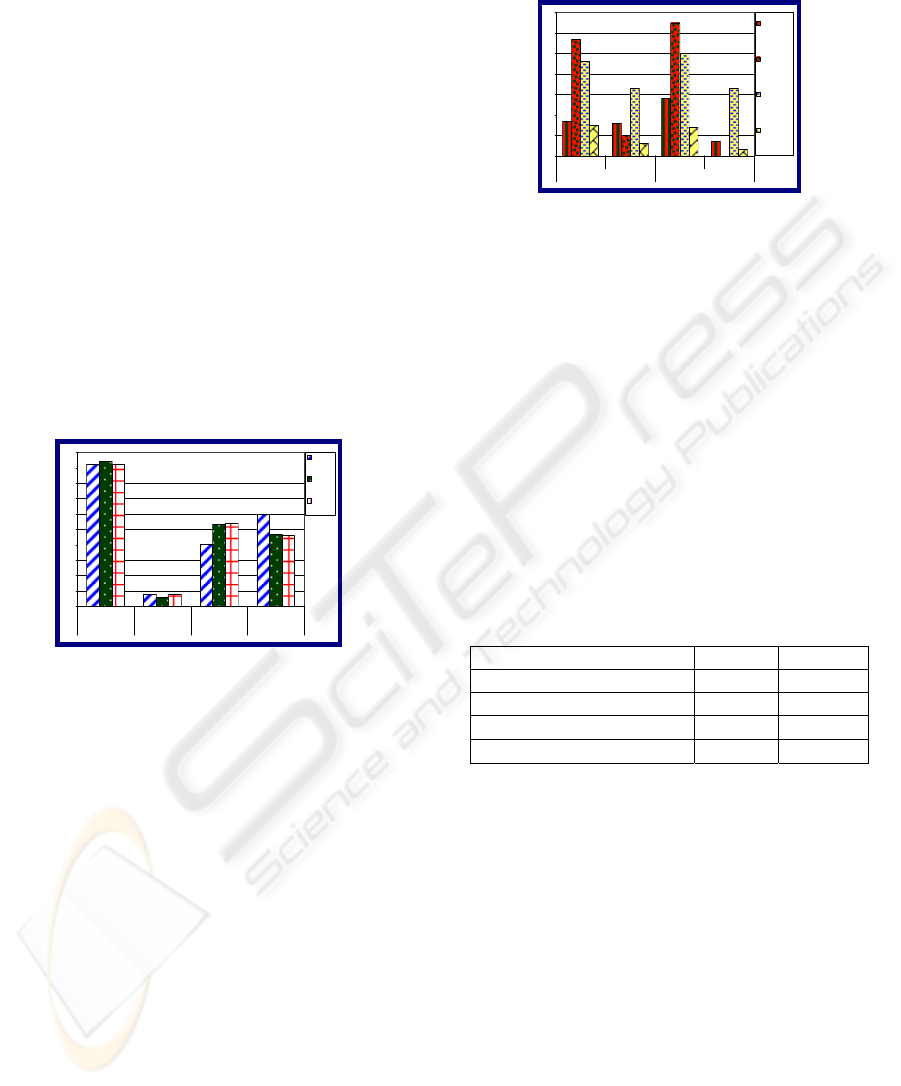

At first we focus on text-based questions that

provide the baseline data for this study. As we can

see in

Figure 4, genuine users answered 74% of text-

based questions correctly, while attackers 49%.

Comparing the genuine users’ answers against the

attackers’ we found that the difference is statistically

significant (Chi-square =19.439, df=1, p<0.001,

two-tailed). These results are comparable to our

earlier study (Nosseir et al, 2005) with 78% and

47% respectively. We take this as an indication that

there is no fundamental difference between the two

types of data as a source of personal information.

These results, although encouraging for genuine

users are a bit disappointing for attackers. However,

a closer look reveals that taking into account the mix

of true/false and four-part multiple-choice text-based

questions, we will expect attackers to answer

correctly approximately 40% of the questions. Note

that this percentage is derived as a weighted sum of

the true/false percentage of 50% and the four-part

multiple-choice percentage of 25%. We conjecture

that the difference between the expected and the

observed percentages are most likely due to the

shared history between participants. We come back

to this issue later on when we examine the

participants’ confidence in their answers.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Correct

Answers

Wrong Answers Correct

Answers

Wrong Answers

Genuine users Attackers

Text

Questions

Image

Questions

Figure 4: Genuine user and attacker performance in text

and image based questions.

Next we look into image-based questions. As we can

see in Figure 4, genuine users answered 93% of

image-based questions correctly and attackers 48%.

Comparing the genuine users’ answers against the

attackers’ we found that the difference is statistically

significant (Chi-square =39.033, df=1, p<0.001,

two-tailed). From these results there appears to be an

improvement in the genuine users’ ability to answer

the questions correctly. Statistical tests confirm that

this improvement is significant (Chi-square =7.793,

df=1, p<0.01, two-tailed). On the other hand, the

attackers’ ability to answer questions correctly at

first appears almost unchanged. However, a closer

look reveals that taking into account the mix of

true/false and four-part multiple-choice image-based

questions, we will expect attackers to answer

correctly approximately 34% of the questions. As a

result, it may be the case that attackers’ performance

improved. However, statistical tests show that there

is in fact no significant difference. From the above

results, we conclude that using an image-based

A STUDY IN AUTHENTICATION VIA ELECTRONIC PERSONAL HISTORY QUESTIONS

67

formulation of questions is beneficial for

authentication purposes, as it significantly improves

genuine users’ performance without any significant

impact for attackers.

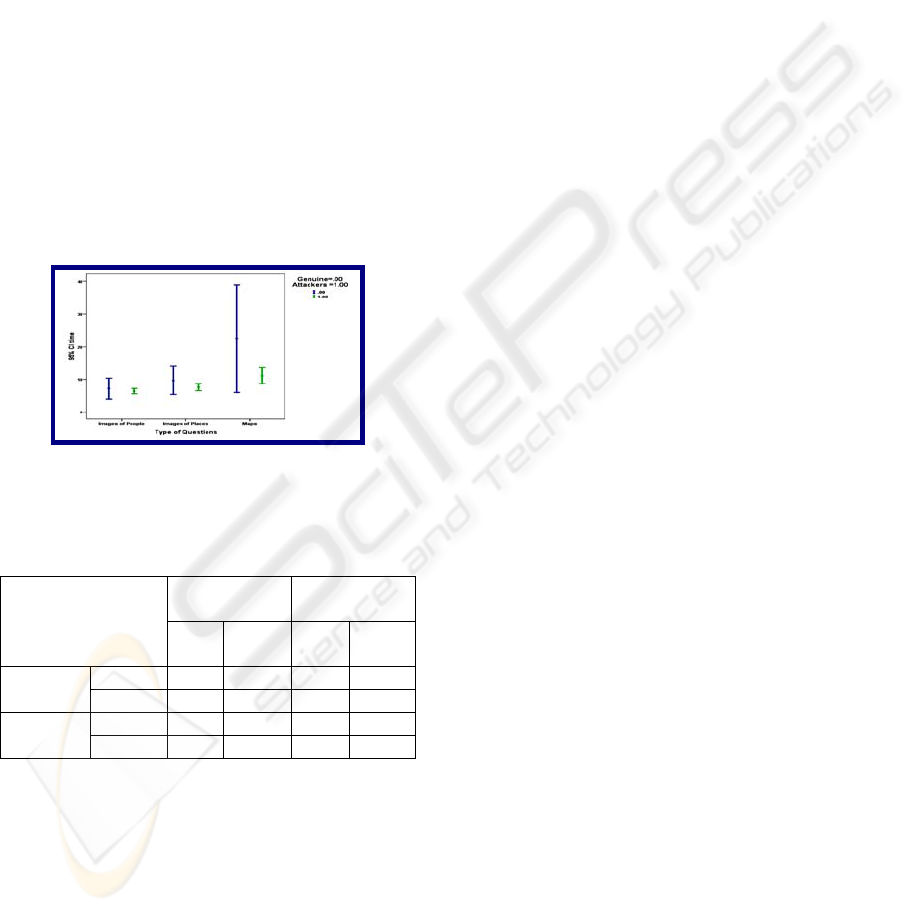

Next we look at the different types of image-

based questions, i.e. images of people, images of

places and maps, to see how each type performs. As

we can see in Figure 5, the performance of genuine

users is pretty similar across all types of image-

based questions, 92%, 94% and 92% correct answers

for images of people, images of places and maps.

However, the performance of attackers shows some

noticeable variation. Although their performance is

pretty similar for images of places and maps with

53% and 54% of correct answers respectively, for

images of people it drops to 40%. In fact, it is their

performance in images of people that drops their

overall performance to 48%. The reasons for this

variation in the performance of attackers are not

clear. As a result, this issues needs to be investigated

further in the future.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Correct Wrong Correct Wrong

Genuine Users Genuine Users Attacker Attacker

Images

of

People

Images

of

Places

Maps

Figure 5: Genuine user and attacker behaviour per type of

image-based question.

We now focus on the confidence with which participants

answered their questions. In our analysis we considered

the top two levels of the Likert scale as high confidence,

and the lower three as low confidence. The first

observation from Figure 6 is that genuine users answer

much more questions correctly with high confidence than

attackers. We believe this is because they often really

know the correct answer. The second observation is that

attackers also appear to give the correct answer with high

confidence in 15% of the text-based questions and 14% of

the image-based ones. Surprisingly, these percentages are

quite low, despite the close academic relationships

between the participants. These results also largely explain

the quite high overall correct answers given by attackers.

They confirm our supposition that a person’s personal

history is difficult for others, even those close to her, to

fully know.. history is difficult for others, even those close

to her, to fully know.

The third observation is that there are a number of cases

where both genuine users and attackers give wrong

answers with high confidence. Based on informal

discussions with the participants, we attribute this

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Correct Wrong Correct Wrong

Text Questions Image Questions

Genuine

users Low

confidence

Genuine

users High

confidence

Attackers

Low

confidence

Attackers

High

confidence

Figure 6: Genuine user and attacker confidence in their

answers for text and image-based questions.

to confusion with some of the questions. It is

interesting to note that there appears to be a lot less

confusion with image-based questions than text-

based ones. Another interesting point is that when

participants have low confidence in their answers,

genuine users tend to give correct answers more

often than not, 52% and 79% for text-based and

image-based questions respectively. However,

attackers tend to give more often wrong answers,

61% and 60% for text-based and image-based

questions, respectively. The reasons behind this are

not clear and require further investigation in the

future.

Table 1: Time taken for genuine users and attackers to

answer questions.

Time Mean Std Dev

Genuine users – text 7.5287 9.50990

Genuine users – image 11.5926 15.94273

Attackers – text 5.2278 5.62078

Attackers – image 7.8517 8.23032

We then turn our attention to the time taken to

answer the questions. As we can see in

Table 1,

attackers take on average less time than genuine

users to answer their questions. However, this

difference is not statistically significant. Another

interesting observation is that on average both

genuine users and attackers take longer to answer

image-based questions, however again the difference

is not statistically significant. We have also analysed

how long participants took to answer each type of

image-based question. As we can see in

Figure 7,

map questions take on average noticeably longer to

answer for both genuine users and attackers.

However, this difference is not statistically

significant. It is also interesting to note that map

questions also have the greatest standard deviation.

The final issue we examine is how the number of

options affects the ability of participants to answer

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

68

questions correctly. As we can see in

Table 2 for

genuine users there is a drop in the percentage of

correct answers for four-part multiple-choice

compared to True/False questions for both text-

based and image-based formulations. However,

statistical tests show that these differences are not

significant. The situation is different when we

examine the attackers. As we case see in

Table 2 in

this case there is a noticeable drop in the percentage

of correct answer as we move from True/False to

four-part multiple-choice questions for both text-

based and image-based formulations. Statistical tests

confirm that in both cases this difference is

significant with (Chi-square =13.909, df=1, p<0.001,

two-tailed) for text-based and (Chi-Square =9.500,

df=1, P<0.005, two-tailed) for image-based

formulation. From these results we conclude that

increasing the number of options is beneficial for

authentication purposes as it significantly reduces

attackers’ performance without any significant

impact for genuine users.

Figure 7: Time taken to answer different types of image-

based questions.

Table 2: Genuine user and attacker performance in

true/false and multiple-choice questions.

Genuine

Users

Attackers

Text Image

Text

Imag

e

True/

False

Correct 77% 96% 54% 57%

Wrong 23% 4% 46% 43%

Multiple

Choice

Correct 68% 91% 40% 42%

Wrong 32% 9% 60% 58%

4.2 Study Conclusions

The first conclusion is that an image-based

formulation of questions is certainly beneficial. It

provides a significant improvement to genuine user

performance. In fact, it brings genuine user

performance within the range of being definitely

appropriate for authentication purposes with more

than 90% correct answers. It also has some impact in

reducing user confusion. More importantly, all these

advantages are realized without any improvement in

attacker performance, i.e. no increase in

vulnerability against guessability attacks.

The second conclusion is that a small increase in

the number of distracters in closed questions is also

beneficial. As it would be expected, it makes things

more difficult for attackers by reducing their chances

of guessing the correct answer. More importantly,

though, it does not have any significant impact on

genuine user performance. In general, the more

distracters we use the worse the performance of

attackers should be however it is not clear how far

we can go before the genuine user performance

begins to suffer. We should point out that a similar

effect to attacker performance could also be

achieved by increasing the number of questions.

Again, it is unclear what the impact of this would be

on genuine user performance. More interestingly, it

is also unclear how the two approaches, using more

distracters and more questions, could be combined

to improve overall authentication performance.

These are points we intend to explore in the future.

The third conclusion is that the ability of

attackers to answer genuine users’ questions

correctly with high confidence is in general quite

low. This is true even though the study was carried

out within a single academic department and focused

on personal history information from academic

personal web sites. This is really encouraging for the

appropriateness of personal history information for

authentication purposes. However, it would be also

interesting to see whether these results will hold, if

the attackers are selected based on their closeness to

the genuine user instead.

The final conclusion is that despite the positive

impact of increasing the number of distracters, and

the encouraging results with respect to the ability of

attackers to answer correctly with high confidence

genuine users’ questions, attackers’ performance is

quite good overall. Identifying techniques that could

make attacker performance more acceptable should

be the focus in future work. In this respect, the

primary aim is to investigate the impact of using

multiple questions. Another idea is to use an

inference mechanism in the generation of the

questions that tests the knowledge acquired by

experiencing an event, not just knowledge of the

event details. This would make things a lot more

difficult for attackers, but of course additional

research is needed to find good ways of doing this.

Note that we have already used simple forms of

inference in our second study where sensor data

were used to infer user arrival and departure events,

A STUDY IN AUTHENTICATION VIA ELECTRONIC PERSONAL HISTORY QUESTIONS

69

and in generating the image-based formulation of the

questions in the current study.

5 SUMMARY AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper we presented a study that is part of a

wider investigation into the appropriateness of

electronic personal history information for

authentication purposes. The study used academic

personal web site data as a source of personal history

information. The main aim of the study was to

examine the effect of using an image-based

formulation of questions about personal history

events. In contrast, to most other work in this area,

the study followed a methodology that assesses the

impact on both genuine users and attackers (others

close to the genuine users). The study concluded that

an image-based representation of questions is

certainly beneficial from an authentication point of

view. It also concluded that a small increase in the

number of distracters used in closed questions has a

positive effect to authentication performance. In

addition to this, the study also showed that despite

the closeness of the attackers their ability to answer

correctly with high confidence questions about the

genuine users’ personal history is limited. These

conclusions contribute positive results to the wider

investigation into the appropriateness of electronic

personal history information for authentication

purposed.

Besides the points identified above, moving this

investigation forward requires that we adopt a wider

perspective. So far, our investigation has exclusively

focused on the performance of genuine users and

attackers in answering correctly the generated

questions. As the results in this front are

encouraging, it is now time to consider additional

aspects that determine the appropriateness of the

approach for authentication. The main issue is to

determine to what extent and in which contexts such

an authentication mechanism would be acceptable to

users. User acceptance relies primarily on two

aspects. How effective and efficient the mechanism

is to use, and whether this use of personal data is

acceptable to users. In doing so, we need to study

the mechanism in specific contexts, e.g. for

authentication to online services, or authentication to

users’ personal mobile devices, etc.

In conclusion, authentication via electronic

personal history questions seems very promising in

comparison to other usable authentication schemes.

Our initial studies show some encouraging results

for its feasibility; however further research is

necessary before a concrete authentication

mechanism can be produced.

REFERENCES

Brostoff, A., Improving password system effectiveness

Department of Computer Science, University College

London UCL, Doctor of Philosophy Thesis, 2004.

Davis, D., Monrose, F. and Reiter, K., On User Choice in

Graphical Password Schemes. In Proc 13th USENIX

Security Symposium,(2004), 151-164.

De-Angeli, A., Coutts, M., Coventry, L., Johnson, G.,

Cameron, D. and Fischer, M., VIP: A Visual

Approach to User Authentication. In Proc Advanced

Visual Interfaces AVI, ACM Press, (2002), 316-323.

Dhamija, R., Hash Visualization in User Authentication.

In Proc. (CHI), ACM Press, (2000), 279 – 280.

Harper, R., Rodden, T., Rogers, Y. and Sellen, A., (Eds.),

Being Human: Human-Computer Interaction in the

year 2020. Cambridge, Microsoft Research Ltd., 2008.

Just, M., Designing and Evaluating Challenge Question

Systems." In Proc IEEE Security & Privacy: Special

Issue on Security and Usability, 2,(5), (2004), 32- 39.

Passface, Real-User Passfaces™,

http://www.passfaces.com.

Pering, T., Sundar, M., Light, J. and Want, R.,

Photographic Authentication through Untrusted

Terminals, Security & Privacy, 2, (1), (2003),30-36.

Nosseir, A., Connor, R. and Dunlop, M., Internet

Authentication Based on Personal History – A

Feasibility Test, Workshop on Customer Focused

Mobile Services at WWW 2005, (2005).

Nosseir, A., Connor, R., Revie, C. and Terzis, S.,

Question-Based Authentication Using Context Data,

ACM Nordic Conference on Human Computer

Interaction (NordiCHI 2006), Oslo, Norway, (2006).

Takada, T and Koike, H., Awase-E: Image-based

Authentication for Mobile Phones Using User’s

Favourite Images, Human-Computer Interaction with

Mobile Devices and Services, 2795, (2003). 347-351.

Wiedenbeck, S., Waters, J., Birget, J.C., Brodskiy, A. and

Memon, N., Authentication Using Graphical

Passwords: Effects of Tolerance and Image Choice. In

Proc. Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security

(SOUPS), ACM Press, (2005), 1-12.

Yan, J., Blackwell, A., Anderson, R. and Grant, A.,

Password Memorability and Security: Empirical

Results, IEEE Security & Privacy, 5,(2), (2004), 25-

31.

Zviran, M. and Haga, W., Cognitive Passwords: the Key

to Easy Access Control, Computers and Security, 9,

(1990),723-736.

Zviran, M. and Haga, W., A Comparison of Password

Techniques for Multilevel Authentication

Mechanisms, The Computer Journal, 36,(3), (1993),

227-237.

ICEIS 2010 - 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

70