TOWARDS E-CONVIVIALITY IN WEB-BASED SYSTEMS

Sascha Kaufmann and Christoph Schommer

Department of Computer Science, University Luxembourg, 6 Coudenhove-Kalergi, 1359 Luxembourg, Luxembourg

Keywords:

Web intelligence, e-Conviviality, Cognition systems, Data mining.

Abstract:

Our belief is that conviviality is a concept of great depth that plays an important role in any social interaction.

A convivial relation between individuals is one that allows participating individuals to behave and interact with

each other following a set of conventions either shared, commonly agreed upon or at least understood. This

presupposes implicit or an explicit regulation mechanism based on consensus or social contracts and applies to

the behaviours and interactions of participating individuals. With respect to web-based systems, an applicable

social attribute is to assist another user, guide him/her in unclear situations and help him in making the right

decision whenever a conflict arises. Such a convivial social biotope deeply depends on both implicit and

explicit co-operation and collaboration of natural users inside a community. An individual conviviality may

benefit from the “wisdom of the crowd”, which means that a dynamic understanding of the user’s behaviours

heavily influences the individual well being of other persons. To achieve that, we present the system CUBA

which targets at user profiling while making a stay convivial via recommendations.

1 INTRODUCTION

We are concerned with the question of how e-

conviviality can be achieved in a web-based system.

In general, a concrete definition of e-conviviality does

not exist and there is neither a clear model nor a

singular vision of how it can be realized. A usage

of the word in a communication environment like

the World-Wide Web is often understood as a layout

problem. Moreover, the relationship of conviviality to

terms like amicability or comfort ability remains flu-

ent: does conviviality refer to a place or a situation

where someone is welcomed and/or feels well? Can

conviviality be computed by algorithmic parameters,

being adjusted and adapted? May external signal be

considered and internal rules be activated such that we

can obtain conviviality?

In literature, there exist several definitions of what

natural conviviality is, e.g. (Britannica, 2008). But es-

pecially in the area of computer science, a convincing

definition for e-conviviality is missing. It is mentioned

that e-conviviality is widely used as a synonym of a

user-friendly event, being often equated with Graphi-

cal User Interfaces. It occurs also in conjunction with

digital cities and normative agents (Caire, 2007), De-

sign Processes (Fischer and Lemke, 1988) or more

generally in the context of sharing and enjoying a

“good time” with others.

An interesting idea is proposed by (Illich, 1998)

who associates conviviality with software tools as the

result of a conscious decision: “I am aware that in En-

glish convivial now seeks the company of tipsy jolli-

ness, which is distinct from that indicated by the Old

English Dictionary and opposite to the austere mean-

ing of modern eutrapelia, which I intend. By applying

the term convivial to tools rather than to people, I hope

to forestall confusion.” And, in fact, (Illich, 1998)

intends to bring the technology to the level of “ordi-

nary” people making it accessible (and hence usable)

to everybody. The idea is to enable (potentially all)

users to use technique in a better/smoother way. In-

stead of certain specifications on how convivial (soft-

ware) tools should look like or should be used, Illich

proposes some characteristics of convivial (software)

tools. Unfortunately, these guidelines have not been

intended to the World Wide Web.

2 WISDOM OF CROWD

With respect to e-conviviality, a promising approach

is to foster the principles of wisdom of crowd. The

term has been populated by (Surowiecki, 2005), who

argues that situations exist where a group of people

(crowd) come up with a better solution to a problem

than the group’s smartest individual (person, expert).

502

Kaufmann S. and Schommer C. (2010).

TOWARDS E-CONVIVIALITY IN WEB-BASED SYSTEMS.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence - Artificial Intelligence, pages 502-506

DOI: 10.5220/0002705105020506

Copyright

c

SciTePress

However, to be authentic, a certain number of con-

ditions must be fulfilled to gain from the wisdom of

crowd. Following (Surowiecki, 2005), the diversity

of the existing points of view, a decentralisation and

the independence of the participants, and a form of

aggregation must exist. The main idea behind the

diversity of points of view is that knowledge – being

unavailable for experts (the so called private or lo-

cal knowledge) – must be collected when it is used

for the final solution. To ensure that such knowledge

is not influenced by other group members, there ex-

ist certain requirements such as decentralisation and

independence. At the end, an independent instance

aggregates the different knowledge to the wisdom of

crowd. This can be obtained in different ways, which

means that there is no well-defined way of coming up

with the perfect solution.

We believe that e-conviviality is a concept of

greater depth that plays an important role not only in

social interactions but also in the internal regulation of

social systems. Convivial relations between individu-

als are the ones that allow individuals to behave and

interact with each other following a set of conventions

either shared, commonly agreed upon or at least un-

derstood. This presupposes implicit or explicit mech-

anisms, which are based on consensus or social con-

tracts, and applies to the behaviour and interactions

of participating individuals. We think that individuals

inside the community may benefit from the wisdom of

crowd, which means that a dynamic understanding of

the users’ behaviour may heavily influence the well

being of individuals.

3 A CONVIVIALITY ENGINE

With CUBA (Conviviality and User Behavior Analy-

sis), we follow the given concepts and focus on as-

pects that are concerned with usability and content

awareness. We foster presentation of the right infor-

mation at the right time in a direct way through the

principle of personalization. We believe that this will

influence the level of conviviality during the stay on

the web page. The aim is to allow the visitor to use

the environment in a free way and to recommend him

content, which he might be interested in. This is ac-

complished by an analysis of: a) how does user orga-

nize his content, b) how does he act during his stay at

the web system and c), to what extent can the crowd

reasonably contribute. Our understanding is that the

combination of these factors helps the user to experi-

ence conviviality.

3.1 A Set of Topics

We primarily take advantage of the Non-Obvious Pro-

file (NOP) approach, which was introduced by (Mush-

taq et al., 2004) and extended in (Hoebel et al., 2006).

The main idea is to define a set of topics Tp

i

that de-

scribes the content of a web site in a proper way

Topics = {Tp

i

} (1)

with i = 1, . . . , n. With respect to this, a topic Tp

i

also corresponds to a certain area of interest. A weight

indicates the relative importance of a topic to the con-

tent, having a value between

0 ≤ Tp

i

(content

h

) ≤ 1 (2)

and reflects the level of interest ranging from

not relevant to very relevant (i = 1, . . . , n and h =

1, . . . , m).

3.2 Zone Weighting

In its first version, CUBA implements a newsreader,

where users can selec feeds they are interested in.

Each feed f

i

is displayed in its own zone Zone

f

i

with

associated topic weights Tp

i

( f

i

), reflecting the con-

tent of the feed.

CUBA allows web pages with an individual layout

of sets of zones. Note that in our case it is therefore

not possible to assign static topics and values to such

web pages. To calculate Page

j

(Tp

i

) we come up with

the following model: in general, a page reflects the

interests of an user. CUBA supports the (re-) arrange-

ment of feeds that will usually lead to a placement

of interesting feeds at the top of the page. We then

calculate Page

j

(Tp

i

) by targeting all zones Zone

k

(Tp

i

)

of Page

j

weighting each zone with respect of the im-

portance for the user. For this, a diverse number of

strategies has been considered, where some of them

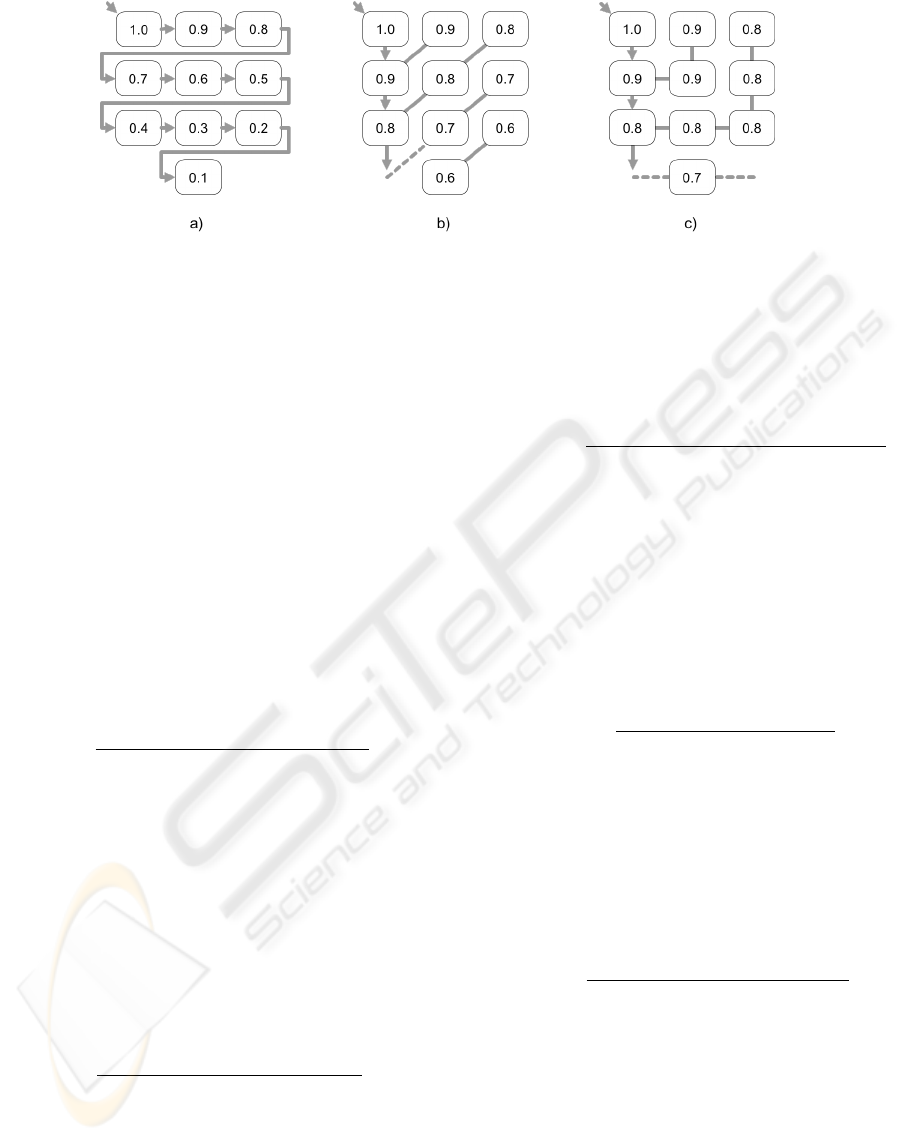

are presented in Figure 1:

• the dovetailing strategy follows the assumption

that the more a user is interested in a content the

higher the assigned value will be.

• the coating strategy says that the left-most/top-

most content receives the highest weight again but

that in contrast to the dovetailing strategy each fol-

lowing inverse coat – identified by the diagonal –

is assigned the same weight.

• the waving strategy, where we perform a weight-

ing following the radius around the top content.

TOWARDS E-CONVIVIALITY IN WEB-BASED SYSTEMS

503

Figure 1: Example of possible value assignment strategies for a layout with 3 rows (a) dovetailing, b) coating, and c) waving).

The boxes represent content with their (relative) importance for the user. Arrows represents the way of calculation.

3.3 Interest Profile

We see an Interest Profile (IP) as a way of modeling

the level of the users’ interest in topic Tp

i

. Within

a session, the visiting time and all actions on each

page are recorded. When the user quits the system,

the NOP-algorithm automatically computes the inter-

est profile of the user. This is done in two steps, each

considering a different approach: in the first step, the

Duration Profile DurP(i) for each topic i is calculated.

We hereby take into account the duration of viewing

Page

j

(Tp

i

) in relation to the total time of viewing all

pages. This part reflects the users’ “general” interests,

because it considers the page layout and how long the

user “read” (i.e. stayed at) a page:

DurP(i) =

∑

j

(duration (Page

j

) ∗ Page

j

(Tp

i

))

∑

t

duration(Page

t

)

(3)

Next, we determine the Action Profile ActP(i) for

all Tp

i

. We include all actions involved with Tp

i

and

multiply this value by the number of topics Tp

i

of the

zone where they occurred. The result is also set in

relation to the total sum of all actions that are involved

with Tp

i

during the whole session. This part takes

the current interests of a user into account. It is also

possible to model different kind of actions (e.g. open

an article may be a stronger indicator than reading the

article’s preview):

ActP(i) =

∑

k

(

∑

l

Action

l

(Tp

i

) ∗ Zone

k

(Tp

i

))

∑

s

Action

s

(Tp

i

)

(4)

Finally, we combine both profiles by calculating

NOP

Session

(Tp

i

) = α ∗ ActP(i) +β ∗ DurP(i) (5)

where α + β = 1 and i = 1, . . . , n in order to deter-

mine the NOP

Session

for this session.

The new NOP then replaces the old one (if exist-

ing). This is done with

NOP

new

(Tp

i

) =

σ ∗ NOP

old

(Tp

i

) + γ ∗ NOP

Session

(Tp

i

)

σ + γ

(6)

with i = 1, . . . , n where we multiply the current

non-obvious profile NOP

cur

by number of sessions σ

and add it to NOP

Session

with a factor γ. We finally

divide it with σ + γ. Here, γ signalizes how strong the

impact of NOP

Session

to the new profile NOP

new

will

be. We inform the user explicitly about his current

interest profile. In case the user updates his interest

profile IP

U

we use

NOP

U

new

(Tp

i

) =

NOP

U

cur

(Tp

i

) + IP

U

new

(Tp

i

)

κ

(7)

with i = 1, . . . , n and κ = 2 to re-calibrate the

user’s current non-obvious profile for further usage.

If the visitor asks for support, then CUBA com-

pares the current interest profile with similar existing

profiles inside the community and recommends con-

tent that may fit following the match. By now, the

euclidean distance between the users does this match-

ing:

d(U

j

, U

k

) =

s

n

∑

i=0

(NOP

U

j

(Tp

i

) − NOP

U

k

(Tp

i

))

2

(8)

This allows CUBA to identify users with similar

interest profiles. As an alternative, we consider to

use the Pearson correlation, because it helps to iden-

tify users with similar differences in their topics. This

could results in different recommendations.

The feedback to the given recommendations (ac-

cept or reject) will influence the visitor’s profile on

CUBA again. This is being done in an indirect way: if

the user accepts a recommendation, the chosen feeds

ICAART 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

504

will become part of his web site. As a result, the page

will be considered as new and its topic weights will

be recalculated and will become part of the duration

profile (3).

However updating all the user profiles may be-

come very expensive. We therefore foster the usage

of clustering in CUBA. The idea is to cluster the pro-

files of the community in a regular interval. When the

profile is modified, we then simply put it in the best

fitting cluster to do further recommendations.

3.4 Measuring Conviviality

The question of how to measure the corresponding

level of conviviality in CUBA leads to asking explic-

itly about the feelings and attitudes of an user. We can

do this for example by introducing a button on each

side, which is something like “I got the desired infor-

mation”. But it will be an additional action for the

user, with no immediate benefit. Instead of using an

explicit determination of the level of conviviality we

chose an implicit approach by using a diverse num-

ber of web-analytic concepts (Sterne, 2002) like for

example

• The duration of stay on the Web Sites. We may

assume that a “longer” stay indicates interest and

corresponds therefore to a higher level of convivi-

ality (3). This practice is also applied to the du-

ration of reading, for example the summary of an

article.

• The question of how many actions the user per-

forms during his visit? A high number of actions

may indicate some kind of satisfaction (4).

• The interval of returning to a web site. A regular

return may indicate a basic interest in the content

provided by the web site.

• The number of accepted recommendations. Ac-

cepted recommendations may also be an indicator

of conviviality because we can derive the quality

of the recommendation algorithm. On the other

hand, it will also be of interest to know how long

the visitor keeps the chosen feeds to get a feeling

how good it covers his needs.

3.5 Introducing Feeds

Taking the former actions and parameters into ac-

count, CUBA creates diverse interest profiles for each

visitor. These profiles are updated regularly whenever

a visitor performs an action. In case that CUBA finds

profiles that are similar to the given profile, CUBA can

recommend interesting feeds or articles. This is an

important topic as the users gain from the knowledge

of all other users. With respect to this, CUBA also

helps to get in touch/contact with other visitors: this

is an essential aspect of the traditional definition of

conviviality of having a good time together.

Figure 2: Graphical representation of a computed Non-

Obvious Profile. Each dot represents a topic. The topic

values are represented by the dots’ positions along the axes,

where they varies between 0 (non interests/center) and 1

(very high interest/outer edge of the wheel). Here, Topic

T

5

has a value of 0, while T

4

and T

9

have a value of 1.

In general, the visitor may subscribe, re-subscribe,

and arrange feeds on the personal page. He is allowed

to update, open and close them, to read a preview of

the selected content and to access it directly. While

a user performs these actions CUBA builds an inter-

est profile of that user as follows: a cancellation of

a feed is understood as a non-interest in its related

topics, whereas other actions like reading a preview

or refreshing a channel are acceptable indicators for

an interest in a channel and its topics. In addition, a

closed channel is understood as a “basic but no cur-

rent interests in the feed”. Another indication might

be the recording of the time with respect to the arti-

cles’ previews. Even the position of the feed can be

taken into account, where a “top-feed” (a feed that is

at the top position) may be more important to the vis-

itor than others. This is, because the user can read it

immediately and without scrolling, even after the per-

sonal page is accessed. In Figure 3, a snapshot with

the areas of the subscribed feeds is presented.

As mentioned in (Fischer and Lemke, 1988) it is

also important to inform the user, why the system is

doing an action to achieve any conviviality (we want

avoid the impression the user is controlled by the sys-

tem). CUBA respects this by giving the user the op-

portunity to examine his current non-obvious profile

(Figure 2) and let him modify his interest profile. In a

future release it is also planed to present informations

about the community to the user.

TOWARDS E-CONVIVIALITY IN WEB-BASED SYSTEMS

505

Figure 3: With CUBA (www.cuba.lu) to foster on Illich’s concept of conviviality. (1) shows a preview of a message, whereas

(2) points to a currently closed channel. In (3), possible actions for a feed are presented, which are – from left to right – check

for new feed entries, open/close a channel, and remove a channel from subscription.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

In this work, we have introduced our concept of

achieving e-conviviality by using the principles of wis-

dom of crowd and presented the “conviviality engine”

CUBA . CUBA is a newsreader which allows the user

to perform several actions. These actions are used to

build (non-obvious) profiles which are the basis for

CUBA’s recommendation system along with mining

profiles of “similar” users. But many questions still

occur: what are generally the reasons for the user’s

actions? It may be normal in a long session to per-

form more actions than in a short one, but if many

actions occur in a short session, we have to guess the

reasons (e.g. is it an experienced user who knows how

to navigate quickly, or does not he find the desired in-

formation and left the site). We may avoid this by

introducing a button on each side, which is something

like “I got the desired information” to get a way out

of this dilemma. But it will be an additional action for

the user, with no immediate benefit.

The best proof of an increased conviviality may be

the visitor’s loyalty, which can be expressed in differ-

ent ways. If the user returns to the web-site in regu-

lar intervals, this possibly shows that the interests and

emotions are met. To achieve this, probably the qual-

ity of the content (news) and the possibility to config-

ure a personal environment is an acceptable argument,

but other ways of attraction like award rankings or of-

fer special services for people with a high loyalty are

interesting as well.

By now, the implementation is performed in a

closed environment. We already have explored the

acceptance of CUBA by a diverse number of user ses-

sions, being focused on the usability to raise the fur-

ther acceptance of the visitors. We have got valuable

comments but mostly positive feedback as well as im-

portant clues to improve the web site.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The current work is funded by the Fonds National de

la Recherche (FNR) and has been conducted at the

MINE Research Group, ILIAS Laboratory, Univer-

sity of Luxembourg. The current version of CUBA

can be accessed by www.cuba.lu.

REFERENCES

Britannica, E. (2008). Encyclopaedia Britannica – Miriam

Webster’s Dictionary and Thesaurus . Encyclopaedia

Britannica.

Caire, P. (2007). A normative multi-agent systems approach

to the use of conviviality for digital cities. In Interna-

tional Conference and Research Center for Computer

Science, Schloss Dagstuhl, Wadern, Germany.

Fischer, G. and Lemke, A. (1988). Constrained Design

Processes: Steps Towards Convivial Computing. In

R. Guindon, ed., ’Cognitive Science and its Applica-

tionfor Human-Computer Interaction’, Lawrence Erl-

baum Associates, Inc., Hillsdale, NJ, USA, pp. 1-58.

Hoebel, N., Kaufmann, S., Tolle, K., and Zicari, R. (2006).

The design of gugubarra 2.0: A tool for building and

managing profiles of web users. In IEEE/WIC/ACM

International Conference on Web Intelligence. IEEE.

Illich, I. (1998). Selbstbegrenzung – Eine politische Kritik

an der Technik. C. H. Beck’sche Verlagsbuchhand-

lung, Muenchen, Germany.

Mushtaq, N., Werner, P., Tolle, K., and Zicari, R. (2004).

Building and evaluating non-obvious user profiles for

visitors of web sites (cec 2004). In International Con-

ference on e-Commerce Technology. IEEE.

Sterne, J. (2002). Web Metrics – Proven Methods for Mea-

suring Web Site Success. Wiley Publishing, New York,

NY, USA.

Surowiecki, J. (2005). The Wisdom of Crowds – Why the

many are smarter than the few. Abacus. London, UK.

ICAART 2010 - 2nd International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

506